Abstract

In recent years, there has been considerable focus on the discovery and characterization of proteins derived from Mycobacterium tuberculosis leading to the identification of a number of candidate antigens for use in vaccine development or for diagnostic purposes. Previous experiments have demonstrated an important immunological role for proteins encoded by the RD1 region, which is absent from all strains of bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) but present in the genomes of virulent M. bovis and M. tuberculosis. Herein, we have studied human T-cell responses to the antigen encoded by the putative open reading frame (rv3878) of the RD1 region. Immunoblot analysis revealed that rv3878 was expressed and the native protein was designated TB27.4. Immunological evaluations demonstrate that TB27.4 elicits a prominent immune response in human tuberculosis patients with a dominant region in the C-terminal part of the molecule. In contrast, very limited responses were seen in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated donors. This study therefore emphasizes the diagnostic potential of proteins encoded by the RD1 region.

Introduction

Despite the widespread use of the tuberculosis (TB) vaccine bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) since the early 1920s, TB remains a major global threat. Alarming data from the World Health Organization estimates that there will be almost 1 billion newly infected individuals, 200 million new TB cases, and 35 million deaths within the next two decades.1 These figures clearly emphasize the urgency of developing a second-generation TB vaccine to replace BCG as well as improved diagnostic tools for the early control of TB.

In recent years, there has been considerable focus on the discovery and characterization of proteins derived from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the intensive search for immunologically active molecules has led to the identification of a number of candidate antigens for use in vaccine development or for diagnostic purposes.2,3 Various strategies have been used to search for immunodominant proteins, including biochemical fractionation,4 serological assays,5 and expression screening of genomic libraries of M. tuberculosis.6 Utilizing these approaches, a number of immunodominant T-cell antigens have been identified. In this regard, fractionation of secreted mycobacterial proteins led to the identification of the early secretory antigenic target (ESAT-6), a well-described antigen found to be highly immunogenic in TB patients.7 The vaccine potential of ESAT-6 has been studied showing the induction of high levels of protection when administered as a single-component subunit vaccine in combination with the adjuvant dimethyl dioctadecyl-ammonium bromide/monophosphonyl lipid A (DDA/MPL)8 or as part of a fusion molecule.9

Comparative genomics has revealed that ESAT-6 is encoded by the RD1 region of the genome, which is absent from all strains of BCG.10 The RD1 region encodes eight proteins of which ESAT-6 has been evaluated intensively for its immunological activity as outlined above.11 Recently, CFP10 was found to give similarly strong T-cell responses and to possess the same immunological properties as ESAT-6.2,12 The absence of ESAT-6 and CFP10 from BCG strains combined with their immunodominance makes these molecules important diagnostic candidates that are capable of distinguishing infection with pathogenic mycobacterial strains from exposure to environmental mycobacteria and BCG vaccination.

Recently, the response to four other predicted proteins from the RD1 region was studied in cattle demonstrating an immunological activity that warrants further investigation.13 In the present study, we have studied the human response to one of these predicted proteins encoded by rv3878, designated TB27.4. Our data demonstrate that TB27.4 elicits prominent responses in human TB patients and possess highly reactive regions recognized by human T-cells.

Materials and methods

Mycobacterial antigens

Recombinant (r) TB27.4 was produced in E. coli using the high-level expression system, pQE-32 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and purified as described previously.14 The protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid test (Micro BCA Protein Assay Reagent kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL). The LPS content of rTB27.4 was measured by the Limulus amoebocyte lysate test and was below 0·001 ng/µg of protein.

ESAT-6 was cloned in the Lactococcus lactis expression vector pAMJ752ESAT-6 as an ESAT-6-ESAT-6 dimer and purified directly from the culture supernatant of Lactococcus lactis strain PSM631 (Biotechnological Institute, Hørsholm, Denmark), transformed with pAMJ752ESAT-6. A growth phase dependent promoter (P170) up-regulated the synthesis of ESAT-6 during the transition to stationary phase while the signal sequence from the usp45 gene promoted secretion. Recombinant ESAT-6 dimer was purified and concentrated by acid precipitation from the culture supernatant; no further purification was required. CFP10 was prepared as previously described.15

Twenty-mer synthetic overlapping peptides covering the complete sequence of TB27.4 were produced by solid-phase methods using an ABIMED peptide synthesizer at Schaefer-N, Denmark. All peptides were purified by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography. The peptides were lyophilized and stored dry until reconstitution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Preparation of M. tuberculosis subfractions: short-term culture-filtrate (ST-CF), cytosol, cell wall, and membrane have been described previously.16 Purified protein derivative (PPD) was obtained from the Statens Serum Institut (tuberculin RT23, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA from M. bovis, M. tuberculosis Erdman, M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. bovis BCG, and M. avium was prepared as previously described.17 15 µg of purified chromosal DNA was digested with PvuII and run on a 1% agarose gel. The agarose gel was blotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham, Life Sciences, Amersham, UK) in a vacuum transfer devise (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Using the two oligonucleotides 5′-TAGCAGCAATCAACGAGACC-3′ and 5′-AGCTGGGTAGCCTGACTTGG-3′ for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification a gene-specific probe was labelled with the Prime-it II labelling kit according to the manufacturer (Stratagene). Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by ethanol precipitation.

Antigen-specific sera

A rabbit was immunized four times with a 4-week interval between each injection with 100 µg of rTB27.4 in 2% Alhydrogel (Superfos Biosector, Frederikssund, Denmark). The rabbit was bled before immunization (negative control) and 2 weeks after the last immunization and the isolated sera tested positive for reactivity against rTB27.4 by Western blotting (results not shown).

Western blot analysis

Twenty µg of M. tuberculosis subfractions were subjected to standard sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) using a 10–20% gradient gel in the Protean IIxi system. The gels were transferred to nitrocellulose as previously described,16 incubated with antiTB27.4 rabbit antibodies, and subsequently with swine anti-rabbit antibody (D306, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark).

Human T-cell lines

T-cell lines from TB-exposed healthy PPD positive Danish donors were generated as previously described with minor modifications.18 In brief, 1–2 × 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) obtained by density centrifugation were stimulated in 24-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in the presence of 5 µg/ml of ST-CF. After 7 days the cells were expanded with 30–50 U/well of r-interleukin (IL)-2 (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and subsequently frozen 7 days later. In order to analyse the antigen responses of the T-cell lines, triplicates of 1·5 × 104 cells were incubated with 5 × 104 irradiated autologous PBMC in a total volume of 200 µl/well in triplicate in 96-well flat-bottomed microtitre plates (Nunc) and stimulated with antigen as indicated. Only T-cell lines responding to PPD and not to an irrelevant antigen (tetanus toxoid) were used in this study and phytohaemagglutinin was included as a positive control. After four days of antigen stimulation, supernatants were harvested and analyzed for the presence of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a commercially available pair of monoclonal antibodies (Endogen, Waburn, MA). Responses of >55 pg IFN-γ/ml were regarded as positive based on mean values of un-stimulated control wells (n = 28) plus 3 standard deviations.

Human lymphocyte cultures

Twenty-one TB patients admitted to the Department of Pulmonary Medicine, University Hospital of Copenhagen in Denmark or Department of Infectious Diseases, Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands participated in this study (13 males and 8 females; mean age 48 ± 16; age range 27–74). The majority of the patients (14) were from the Netherlands or Denmark, 4 patients were from the Middle Esat, and 3 patients from Africa. All cases (14 with pulmonary TB and 7 with extrapulmonary TB) were confirmed by either culture or microscopy and demonstrated a positive in vitro response to PPD with a median response of 8382 pg/ml of IFN-γ. Blood samples were drawn 0–1 years after initiation of antituberculosis treatment.

Twenty-six BCG vaccinated donors of Caucasian Danish origin were recruited as controls (9 males and 17 females; mean age 40 ± 10; age range 27–65). All BCG vaccinated donors had a positive in vitro response to PPD with a median IFN-γ release of 3142 pg/ml. Based on a questionnaire, BCG vaccinated donors with a history of TB or with known exposure to TB were excluded from the study. Blood samples were drawn between 2 months to 40 years after BCG vaccination. Furthermore, 8 BCG non-vaccinated controls also of Caucasian Danish origin were included in the study (3 males and 5 females; mean age 30 ± 10; age range 18–48). This group had a negative in vitro response to PPD (median 111 pg/ml) and no known exposure to, or history of TB.

PBMC from TB patients, BCG vaccinated, and non-vaccinated individuals were isolated and cultured as previously described.7 After 5 days of antigen stimulation, supernatants were harvested and the IFN-γ release determined by ELISA. All analyses were performed in triplicate from which a mean value was calculated. The variation between individual wells of a triplicate was always less than 10%. A response of >100 pg/ml was regarded as positive based on mean values of unstimulated controls (n = 100) plus 3 standard deviations. The Local Ethics Committee of Leiden University Medical Center (protocol P136/97) and for Copenhagen (RH 01–282/906 and KF 01-369/98) approved the study protocol.

Statistics

Mann–Whitney rank sum test was used for analysing differences between groups.

Results

Identification and characterization of a M. tuberculosis protein from the RD1 region

According to the Sanger database, rv3878 from the RD1 region of M. tuberculosis codes for a hypothetical alanine rich protein with a molecular mass of 27 000 MW (Table 1). Southern blot analysis was performed to identify closely related genes in the genomes of various mycobacterial strains. Mycobacterial DNA was digested with PvuII and probed with rv3878 resulting in hybridization to one band in lanes corresponding to M. tuberculosis Erdman, M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and M. bovis. As expected, no reactivity was seen in lanes with M. bovis BCG Pasteur and M. avium. In agreement with this, TBLASTN searches in the incomplete sequence of M. avium (http://tigrblast.tigr.org/ufmg/) did not reveal any homologous proteins.

Table 1.

Amino acid sequences of synthetic overlapping peptides of TB27.4 used in this study

| Peptide (position) | Amino acid sequence* |

|---|---|

| TB27.4 | |

| p1(2–21) | AEPLAVDPTGLSAAAAKLAG |

| p2(14–33) | AAAAKLAGLVFPQPPAPIAV |

| p3(26–45) | QPPAPIAVSGTDSVVAAINE |

| p4(38–57) | SVVAAINETMPSIESLVSDG |

| p5(50–69) | IESLVSDGLPGVKAALTRTA |

| p6(62–81) | KAALTRTASNMNAAADVYAK |

| p7(74–93) | AAADVYAKTDQSLGTSLSQY |

| p8(86–105) | LGTSLSQYAFGSSGEGLAGV |

| p9(98–117) | SGEGLAGVASVGGQPSQATQ |

| p10(110–129) | GQPSQATQLLSTPVSQVTTQ |

| p11(122–141) | PVSQVTTQLGETAAELAPRV |

| p12(134–153) | AAELAPRVVATVPQLVQLAP |

| p13(146–165) | PQLVQLAPHAVQMSQNASPI |

| p14(158–177) | MSQNASPIAQTISQTAQQAA |

| p15(170–189) | SQTAQQAAQSAQGGSGPMPA |

| p16(182–201) | GGSGPMPAQLASAEKPATEQ |

| p17(194–213) | AEKPATEQAEPVHEVTNDDQ |

| p18(206–225) | HEVTNDDQGDQGDVQPAEVV |

| p19(218–237) | DVQPAEVVAAARDEGAGASP |

| p20(230–249) | DEGAGASPGQQPGGGVPAQA |

| p21(242–261) | GGGVPAQAMDTGAGARPAAS |

| p22(254–273) | AGARPAASPLAAPVDPSTPA |

| p23(261–280)† | SPLAAPVDPSTPAPSTTTTL |

From the N terminus to the C terminus.

Peptide 23 overlaps peptide 22 by 13 amino acids.

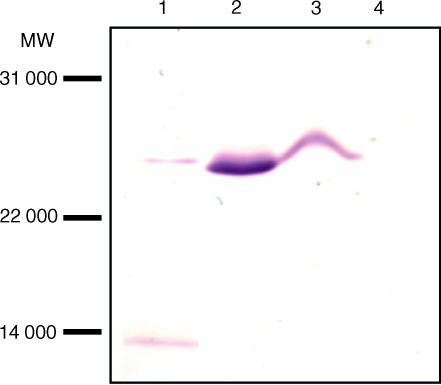

In order to identify and localize the native protein, rv3878 was expressed in E. coli and purified as a histidine-tagged product. A rabbit was immunized with the purified recombinant protein to generate anti rv3878 serum which was used to probe blots containing secreted proteins (ST-CF) of M. tuberculosis H37Rv as well as cell wall, membrane, and cytosol preparations. One major band of a size corresponding to the theoretical molecular weight of rv3878 was highly enriched in the cytosol preparation. Substantial amounts were also found in the membrane preparation whereas smaller quantities were seen in ST-CF (Fig. 1). The antibody also reacted with a band below 14 000 MW, however, this band was observed in several plots probed with rabbit sera against irrelevant proteins (results not shown) and therefore appears to be an unspecific reaction. No reactivity was seen using the preimmune serum (results not shown). These results demonstrate the presence of a reactive 27 000 MW protein in the cytoplasm, membrane and in smaller quantities in ST-CF. The identified native protein was designated with a TB prefix followed by the theoretical calculated molecular weight TB27.4.14

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis of TB27.4. Various subfractions of M. tuberculosis were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analysed for the presence of TB27.4 by Western blotting. Lane 1: ST-CF. Lane 2: cytosol. Lane 3: membrane. Lane 4: cell wall.

Immunological responses to rTB27.4

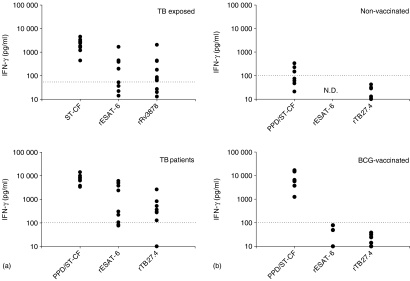

The immunological reactivity to rTB27.4 was evaluated by stimulating T-cell lines as well as PBMC obtained from TB patients (Fig. 2a). T-cell lines were generated by stimulating PBMCs from TB exposed PPD positive healthy donors with ST-CF for a two-week period. The T-cell lines were subsequently restimulated with rTB27.4 and with ST-CF or rESAT-6 for comparison. Using a cut-off level of 55 pg IFN-γ/ml as defined in Materials and Methods, rTB27.4 induced positive responses in 9 out of 12 T-cell lines with mean IFN-γ levels of 285 pg/ml. With a cut-off level of 100 pg/ml as defined in Materials and Methods, positive PBMC responses were also induced in the majority of the TB patients (70%) with a mean response of 500 pg/ml.

Figure 2.

T-cell responses to TB27.4. (a) IFN-γ response of 12 T-cell lines (obtained from TB exposed healthy donors) and of PBMC's from 10 TB patients stimulated with 5 µg/ml of ST-CF/PPD, rESAT-6, or rTB27.4 (only eight of the T-cell lines were stimulated with rESAT-6). (b) PBMCs from eight healthy non-vaccinated donors and eight healthy BCG-vaccinated donors were stimulated as above and the antigen-specific responses measured as IFN-γ release. Responses above 55 pg IFN-γ/ml (T-cell lines) or 100 pg IFN-γ/ml (PBMC) are regarded as positive (as indicated by the dotted line). ND, not determined.

For further evaluation of the immunogenicity of rTB27.4, the ability to stimulate IFN-γ release from PBMC of two different control groups was also assessed. PBMC were purified from healthy BCG-vaccinated Caucasian Danes and non-vaccinated Caucasian Danes and restimulated in vitro with rTB27.4. Moreover, rESAT-6 and a mixture of mycobacterial proteins (PPD or ST-CF) were included for comparison (Fig. 2b). No reactivity to rTB27.4 was seen in the group of BCG-vaccinated or nonvaccinated donors confirming the specificity of the antigen. The IFN-γ response in the group of TB patients was significantly higher than the response seen in BCG-vaccinated (P < 0·05) and nonvaccinated controls (P < 0·05). Taken together, these results demonstrate that TB27.4 is an immunogenic antigen recognized by donors exposed to M. tuberculosis.

Epitope mapping of TB27.4

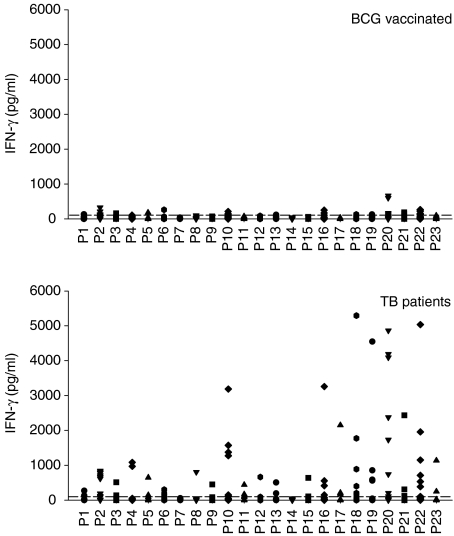

The fine specificity of the T-cell response to TB27.4 was analysed using a panel of overlapping peptides covering the complete TB27.4 sequence. The 23 peptides were synthesized as 20-mer residues with an 8-amino acid overlap (Table 1). For the epitope mapping, a large number of TB patients were screened for reactivity to peptide pools of TB27.4 and thereafter 13 patients with a positive response to one or several pools were selected for further analysis. PBMCs from the 13 TB patients were stimulated with the single synthetic peptides and IFN-γ release measured. As shown in Fig. 3, the C-terminal part of the protein gave rise to the most prominent responses. In this region, covering peptide 16–22 (amino acid 182–273), high IFN-γ responses of more than 1000 pg/ml were seen in several of the donors. In particularly, peptide 20 (amino acid 230–249) induced strong responses with a mean of 1413 pg IFN-γ/ml. A large proportion of the donors (8 out of 13 patients) recognized peptide 2 although at levels lower than 1000 pg/ml. Also the central part of TB27.4 (peptide 10) was recognized by 6 of the 13 patients.

Figure 3.

Mapping of T-cell epitopes using PBMCs isolated from 26 BCG-vaccinated healthy donors and 13 TB patients stimulated with 5 µg/ml of single peptides from TB27.4. Responses above 100 pg IFN-γ/ml are regarded as positive (as indicated by the dotted line).

In parallel, the response of 26 BCG-vaccinated Caucasian Danes with no known exposure or history of TB was studied. In general, very limited IFN-γ responses were seen in this donor group. Only a few peptides (peptide 2, 10, 16, 20, and 22), exhibited a response that was marginally above the cut-off level of 100 pg/ml for more than 3 of the donors. However, all of these peptides induced significant higher IFN-γ responses in TB patients compared to BCG-vaccinated (P < 0·05) except for peptide 10 (P = 0·051). No reactivity to the peptides was seen in unvaccinated, PPD-negative Caucasian Danes (results not shown).

Discussion

The identification of the optimal cocktail of mycobacterial antigens for inclusion in a novel TB vaccine, or for use in various diagnostic assays, has been hampered by the large number of putative proteins in the M. tuberculosis genome. Random cloning and subsequent screening of approximately 4000 genes19 would have been an extensive, laborious and time-consuming task. However, in recent years genomic studies have revealed a high frequency of immunodominant antigens encoded by gene clusters or gene families such as the PPE family3 and the esat-6 family.20 Focusing on these genomic families and clusters has led to more rational, targeted antigen screening and consequently identification of an increasing number of T-cell antigens.

Also the RD1 region of M. tuberculosis has been demonstrated to encode proteins with a significant immunological activity.6,21 This was recently supported by Pym et al.22 in a study using several recombinant BCG strains containing the core region of RD1 with either downstream or upstream portions. The most promising BCG construct, also comprising rv3878, showed enhanced protection compared to the standard BCG vaccine. Previously, ESAT-6 and CFP10 were both found to be potent T-cell antigens recognized by a high frequency of human TB patients2 while more recently, testing of a third RD1 protein (Rv3873) identified the third important target within this region.23 The data presented in this paper demonstrate strong human T-cell responses to the fourth protein, TB27.4, and hence support the immunodominant role of proteins from the RD1 region. By using synthetic peptides, we found that TB27.4 contains several epitopes, particularly in the C-terminal part of the molecule.

Cockle et al. also used synthetic peptides to screen 13 ORFs, including TB27.4, in M. bovis infected cattle.13 Testing TB27.4 in three peptide pools revealed a recognition frequency of 59% for the most active peptide pool in infected animals while the BCG-vaccinated animals did not recognize the antigen. Recently, TB27.4 was found to supplement ESAT-6 and CFP-10 giving rise to a level of sensitivity in M. bovis-infected cattle almost similar to that obtained by PPD without compromising the specificity.14 In the present study, some peptides of TB27.4 recognized by TB patients also exhibited a marginal response in a small percentage of the BCG-vaccinated control donors. In this regard, using peptides as diagnostic markers would be an advantage making it possible to design epitope cocktails with no cross-reactive responses in either BCG-vaccinated persons or individuals exposed to environmental mycobacteria. These peptide cocktails would be suitable for use in an in vitro T-cell assay such as the QuantiFERON-TB® test,24 the sensitive emzyme-linked immunospot assay,25 or as a replacement for PPD in a skin test. TB27.4 does, on the other hand, not constitute an obvious candidate as a serodiagnostic reagent as TB27.4 was found to exhibit very low serological activity.21

New and improved diagnostic technologies to replace the existing tests would have a great impact on the identification of early cases and would consequently limit the transmission of TB in the community. One of the major shortcomings of today's Mantoux test is the low degree of specificity resulting in false positive responses in BCG-vaccinated individuals and individuals exposed to environmental mycobacteria. Antigens of the RD1 region of M. tuberculosis are obvious candidates for the rational design of new specific reagents. Firstly, the genes in the RD1 region are lacking in all BCG substrains as well as the majority of environmental mycobacterial strains.26,27 Secondly, a recent study using deletion analysis demonstrated that the RD1 region is conserved in various M. tuberculosis strains implying that the antigens of RD1 could be used for specific diagnosis worldwide.28 Finally, of the RD1 antigens tested so far, including TB27.4, all contains numerous epitopes distributed throughout the molecule.7,29 This enables the generation of a multipeptide cocktail covering the broad spectrum of HLA polymorphisms seen in genetically different populations. Ongoing studies will reveal whether peptides from TB27.4 can supplement the sensitivity already seen with the combined use of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 in humans.2

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from the European Commision, contract number QLK2-CT-1999–01093, QLRT-2000-02018 and the Danish National Association against Lung Disease.

We thank Dr Axel Kok-Jensen from the Department of Pulmonary Disease, Gentofte Hospital, Denmark, Richard van Altena from the Department of Lung Diseases, Beatrixoord, Haaren, the Netherlands and many physicians at the LUMC, Leiden, the Netherlands for the recruitment of TB patients. We are grateful to Birgitte Smedegaard, Vita Skov, Jette Pedersen, and Kathryn Wattam for excellent technical assistance and Claire Alexandra Swetman and Tom H.M. Ottenhoff for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Tuberculosis. Geneva: WHO; 2000. Fact Sheet no. 104. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Pinxteren LAH, Ravn P, Agger EM, Pollock JM, Andersen P. TB diagnosis based on specific recombinant antigens. Clin Diagn Laboratory Immunol. 2000;7:155–60. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.155-160.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alderson MR, Bement T, Day CH, et al. Expression cloning of an immunodominant family of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens using human CD4 (+) T-cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:551–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sørensen AL, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen AB. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lodes MJ, Dillon DC, Mohamath R, et al. Serological expression cloning and immunological evaluation of MTB48, a novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2485–93. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2485-2493.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillon DC, Alderson MR, Day CH, et al. Molecular and immunological characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CFP-10, an immunodiagnostic antigen missing in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3285–90. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3285-3290.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravn P, Demissie A, Eguale T, et al. Human T-cell responses to the ESAT-6 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:637–45. doi: 10.1086/314640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandt L, Elhay M, Rosenkrands I, Lindblad EB, Andersen P. ESAT-6 subunit vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:791–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.791-795.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen AW, van Pinxteren LAH, Okkels LM, Rasmussen PB, Andersen P. Protection of mice with a tuberculosis subunit vaccine based on a fusion protein of antigen 85B and ESAT-6. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2773–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2773-2778.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahairas GG, Sabo PJ, Hickey MJ, Singh DC, Stover CK. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1274–82. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1274-1282.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brosch R, Gordon SV, Pym A, Eiglmeier K, Garnier T, Cole ST. Comparative genomics of the mycobacteria. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:143–52. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colangeli R, Spencer JS, Bifani P, et al. MTSA-10, the product of the Rv3874 gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, elicits tuberculosis-specific, delayed-type hypersensitivity in guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 2000;68:990–3. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.990-993.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cockle PJ, Gordon SV, Lalvani A, Buddle BM, Hewinson RG, Vordermeier HM. Identification of novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens with potential as diagnostic reagents or subunit vaccine candidates by comparative genomics. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6996–7003. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6996-7003.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aagaard C, Govaerts M, Okkels LM, Andersen P, Pollock JM. Genomic approach to the identification of Mycobacterium bovis diagnostic antigens in cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3719–28. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3719-3728.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berthet FX, Rasmussen PB, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P, Gicquel B. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis operon encoding ESAT-6 and a novel low-molecular-mass culture filtrate protein (CFP-10) Microbiology. 1998;144:3195–203. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenkrands I, Weldingh K, Jacobsen S, Hansen CV, Florio W, Gianetri I, Andersen P. Mapping and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, microsequencing and immunodetection. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:935–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000301)21:5<935::AID-ELPS935>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen P, Askgaard D, Gottschau A, Bennedsen J, Nagai S, Heron I. Identification of immunodominant antigens during infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1992;36:823–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb03144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottenhoff TH, Elferink DG, Termijtelen A, Koning F, de Vries RR. HLA class II restriction repertoire of antigen-specific T-cells. II. Evidence for a new restriction determinant associated with DRw52 and LB- Q1. Hum Immunol. 1985;13:105–16. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(85)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–44. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skjøt RL, Brock I, Arend SM, Munk ME, Theisen M, Ottenhoff TH, Andersen P. Epitope mapping of the immunodominant antigen TB10.4 and the two homologous proteins TB10.3 and TB12.9, which constitute a subfamily of the esat-6 gene family. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5446–53. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5446-5453.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brusasca PN, Colangeli R, Lyashchenko KP, Zhao X, Vogelstein M, Spencer JS, McMurray DN, Gennaro ML. Immunological characterization of antigens encoded by the RD1 region of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome. Scand J Immunol. 2001;54:448–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pym AS, Brodin P, Majlessi L, et al. Recombinant BCG exporting ESAT-6 confers enhanced protection against tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2003;9:533–9. doi: 10.1038/nm859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okkels LM, Brock I, Follmann, et al. The PPE protein (Rv3873) from the RD1 region of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: strong recognition of both specific T-cell epitopes and epitopes conserved within the PPE family. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6116–23. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6116-6123.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brock I, Munk ME, Kok-Jensen A, Andersen P. Performance of whole blood IFN-gamma test for tuberculosis diagnosis based on PPD or the specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:462–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lalvani A, Pathan AA, McShane H, Wilkinson RJ, Latif M, Conlon CP, Pasvol G, Hill AV. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by enumeration of antigen-specific T-cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:824–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.2009100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behr MA, Wilson MA, Gill WP, Salamon H, Schoolnik GK, Rane S, Small PM. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–3. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen P, Munk ME, Pollock JM, Doherty TM. Specific immune-based diagnosis of tuberculosis. Lancet. 2000;356:1099–104. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02742-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brosch R, Gordon SV, Marmiesse M, et al. A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3684–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052548299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arend SM, Geluk A, van Meijgaarden KE, van Dissel JT, Theisen M, Andersen P, Ottenhoff TH. Antigenic equivalence of human T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific RD1-encoded protein antigens ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10 and to mixtures of synthetic peptides. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3314–21. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3314-3321.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]