Abstract

After intravenous injection of Rhodococcus aurantiacus normal mice develop non-necrotic granulomas, the formation of which is dependent on endogenous interferon-γ (IFN-γ). In the early phase of R. aurantiacus infection a high level of endogenous interleukin-6 (IL-6) is detected in the spleen extracts, though its importance is unknown. Using IL-6 knockout (IL-6−/−) mice, we studied the role of IL-6 in granulomatous inflammation induced by R. aurantiacus. The size of granulomas generated in IL-6−/− mice was significantly larger than that of wild-type (IL-6+/+) mice at 2 weeks postinjection (p.i). Moreover, central necrosis of the granuloma was observed in IL-6−/− mice but not in IL-6+/+ controls. Titres of endogenous IFN-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were markedly increased in the spleens and livers of IL-6−/− mice in comparison with IL-6+/+ mice at days 1 through 3 p.i. In vivo administration of either an anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (mAb) or anti-TNF-α mAb to IL-6−/− mice reduced the number and size of granulomas, and prevented formation of necrotic granulomas. In addition, the production of endogenous IFN-γ and TNF-α in the early phase of R. aurantiacus infection by IL-6−/− mice was suppressed by treatment with recombinant IL-6 (rIL-6). This suppression of IFN-γ and TNF-α production was followed by a reduction in the number and size of central necrotic granulomas at 2 weeks p.i. These findings suggest that overproduction of IFN-γ and TNF-α induces central necrotic granuloma formation in IL-6−/− mice, and that IL-6 down-regulates granulomatous inflammation reaction in response to R. aurantiacus infection by modulating production of IFN-γ and TNF-α.

Introduction

As a proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6 (IL-6) is an important regulator of various aspects of the immune response and inflammatory conditions. IL-6 has been reported to play a role in activation and differentiation of macrophages and lymphocytes.1,2 IL-6 is also necessary for the in vivo acquisition of cell-mediated immunity to Mycobacterium avium.3,4 Furthermore, studies using IL-6-deficient (IL-6−/−) mice have revealed that IL-6 is required for resistance to Listeria monocytogenes, vesicular stomatitis virus, and vaccinia virus infections.1,5,6

The formation of granuloma at the site of bacteria proliferation is an essential component of host immunity for controlling infection. This process is regulated by cytokines produced by T cells and other immunocompetent cells. On the basis of cytokine profiles, granulomatous inflammation can be classified into two types. Type 1 is characterized by the predominance of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-12, while type 2 is typified by production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10.7,8 Although high levels of IL-6 have been detected in type 1 granulomatous inflammation induced by bacille Calmette–Guérin and M. tuberculosis,9,10 and type 2 induced by Schistosomiasis mansoni,5 the importance of IL-6 in granuloma formation is unknown.

To determine if there are critical functions for IL-6 in granuloma formation, we infected IL-6−/− mice with Rhodococcus aurantiacus, a psychrophilic acid-fast bacterium closely related to members of the genera Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium and Nocardia. Our previous studies showed that R. aurantiacus induces IFN-γ-dependent non-necrotic and epithelioid type 1 granuloma formation in wild-type (IL-6+/+) mice.11,12 Herein, we report that IL-6 deficiency results in up-regulation of granulomatous inflammation and necrosis of granulomas induced by R. aurantiacus infection.

Materials and methods

Mice and experimental infections

Control C57BL/6 IL-6+/+ mice and IL-6 gene knockout mice (IL-6−/−) were purchased from SLC (Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan) and The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), respectively. IL-6−/− mice were generated as previously described.1,5 Briefly, 129Sv × C57BL/6 mice with a disrupted IL-6 gene were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background to obtain mice homozygous for the mutation. Female C57BL/6 IL-6−/− mice and C57BL/6 IL-6+/+ mice, 6–8 weeks old, were used.

Mice were infected via a lateral tail vein with 108 colony-forming units (CFU) of viable R. aurantiacus (strain 80005) suspended in 0·2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). They were killed at the indicated times postinjection (p.i).

Administration of recombinant mouse IL-6 (rIL-6)

One µg of rIL-6 (R&D Systems, Inc., MN) was administered intravenously to IL-6−/− mice at day −1of R. aurantiacus infection. PBS was injected as a control.

In vivo depletion of endogenous IFN-γ or TNF-α

Anti-mouse IFN-γ monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and anti-mouse TNF-α mAb for in vivo depletion were prepared from hybridoma cell lines secreting a mAb against murine IFN-γ (R4-6A2; rat immunoglobulin)13 or murine TNF-α (MP6-XT22·11; rat immunoglobulin),14 as described previously.15 To deplete endogenous IFN-γ or TNF-αin vivo, 1 mg of either anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb or anti-mouse TNF-α mAb was injected intravenously into mice on day −1 before R. aurantiacus infection. Normal rat globulin was injected as a control.

Determination of number of bacteria in the organs

The organs were suspended in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco Laboratories, Grand Island, NY) (g/10 ml) and organ homogenates were prepared with a Dounce tissue grinder. The numbers of viable R. aurantiacus in the spleens and livers of infected mice were counted by plating serial 10-fold dilutions of organ homogenates in RPMI-1640 medium on nutrient agar plates (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Bacterial colonies that developed on the plates were counted after 48 hr of culture.

Preparation of organ extracts

Spleen extracts or liver extracts for cytokine assays were prepared as follows: spleens or livers were aseptically removed from mice and suspended in RPMI-1640 medium containing 1% (wt/vol) 3-[(cholamidopropyl)-dimethyl-ammonio]-1-propane-sulphonate (CHAPS: Wako Pure Chemical Co., Kyoto, Japan), and 10% (wt/vol) homogenates were prepared with a Dounce grinder. The homogenates were clarified by centrifugation at 2000 g for 25 min The supernatants were stored at −80° until cytokine assay.

Cytokine assays

Cytokine concentrations in the organ extracts were measured by double-sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). To measure IFN-γ, plates were coated with purified rat anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb produced by hybridoma R4–6A2 and incubated with organ extracts. IFN-γ was detected with rabbit polyclonal anti-recombinant murine IFN-γ serum followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc., Avondale, PA) and o-phenylenediamine (Wako Pure Chemical Co.) substrate.11,12 All ELISAs were run with recombinant murine IFN-γ (Genentech, Inc., San Francisco, CA). TNF-α was determined as described previously.16 Purified hamster anti-mouse TNF-α mAb (Genzyme Co., Boston, MA) and rabbit polyclonal anti-recombinant murine TNF-α serum were used as capture and detecting antibodies, respectively. A standard curve was constructed for each experiment by serially diluting recombinant mouse TNF-α (Genzyme Co.). The IL-6 concentration was also determined by ELISA. Briefly, 100 µl of sample and recombinant mouse IL-6 (Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) were, respectively, added to microtitre wells coated with the purified rat anti-mouse IL-6 mAb (MP5-20F3, Pharmingen), and IL-6 was detected with a biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-6 mAb (MP5-32C11, Pharmingen). The sensitivities of the ELISA were 0·1 IU/ml for IFN-γ, 20 pg/ml for TNF-α and 50 pg/ml for IL-6.

Histology

Granuloma area was measured from a separate set of formalin-inflated livers that were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 µm thickness, then stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). In each experiment, sections were made from 6 to 8 pieces of each organ. The size of the granuloma was calculated by the diameter of each granuloma measured with an ocular micrometer. The mean size of a granuloma and the mean number of granulomas per field were measured from 10 random optical fields within each section. Granuloma area was determined from the size of granuloma multiplied by the number of granulomas.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times and accepted as valid if the data were reproducible. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences between the values in experimental and control groups were calculated by Friedman's test. Values of P < 0·01 were considered significant.

Results

Kinetics of endogenous IL-6 production in R. aurantiacus infection

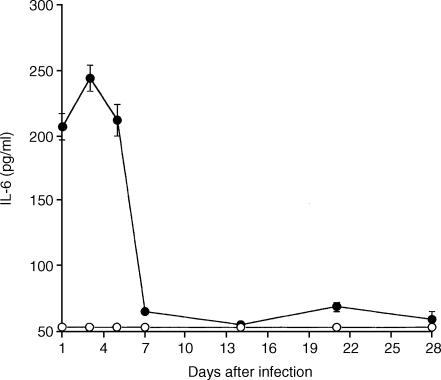

Titres of IL-6 were measured sin spleen extracts of infected IL-6+/+ mice and IL-6−/− mice by ELISA. In the IL-6+/+ mice, IL-6 was detected in the spleen and reached a maximum on day 3 p.i. No IL-6 was detected in spleen extracts of the infected IL-6−/− mice (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Kinetics of endogenous IL-6 production from days 1–28 p.i. in spleen extracts of R. aurantiacus-infected IL-6+/+ mice and IL-6−/− mice. IL-6 was produced during infection with maximal production on day 3 p.i. No IL-6 was detected in spleen extracts of the IL-6−/− mice. Each point represents the mean ± SD for 6–10 mice.

Kinetics of R. aurantiacus–induced granuloma formation

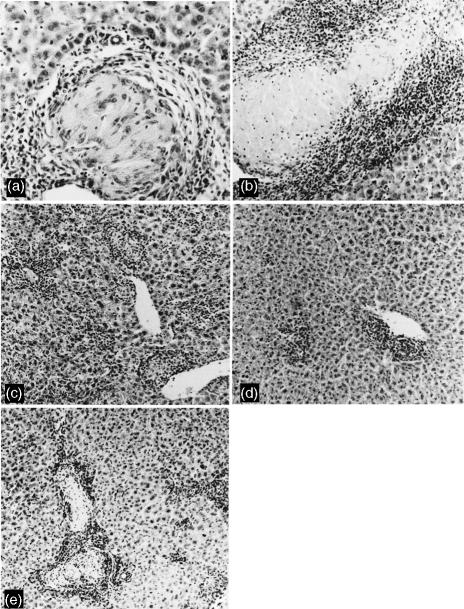

Granuloma formation in the liver was investigated histologically over the course of infection in IL-6+/+ mice and IL-6−/− mice injected with R. aurantiacus. Granuloma formation was observed in both groups of mice, but the sizes of granulomas and their histopathological features were remarkably different between the two groups. In the control group mononuclear cells and lymphocytes infiltrated the liver at 1 week p.i., and non-necrotic and epithelioid granulomas in the liver grew to maximum size at 2 weeks p.i. (Figs 2a and 3). Thereafter, the number of granulomas decreased and the granulomas regressed completely at 4 weeks p.i. When R. aurantiacus was injected to the IL-6−/− mice, massive infiltration of inflammatory cells into the liver occurred. Granuloma formation in IL-6−/− began at 1 week p.i and peaked in size at 2 weeks p.i. These granulomas were significantly larger than those of normal controls, and characterized by central necrotic areas throughout tissue sections of the livers (Figs 2b and 3). No epithelioid macrophages were evident in the necrotic lesions. The granulomas of IL-6−/− mice regressed completely at 5 weeks p.i.

Figure 2.

Histological appearance of livers of IL-6+/+ mice (a), IL-6−/− mice (b), IL-6−/− mice treated with anti-IFN-γ mAb (c), anti-TNF-α mAb (d), and rIL-6 (e) at 2 weeks p.i. A non-necrotic and epithelioid granuloma is seen in the liver of an IL-6+/+ mouse (a), while a large granulomatous lesion with a central area of necrosis is developing in the tissue of IL-6−/− mouse (b). Treatment of IL-6−/− mice with either anti-IFN-γ mAb (c) or anti-TNF-α mAb (d) caused extensive decreases in both number and size of granulomas, and no necrotic granulomas are observed. Administration of rIL-6 reduced the area of necrotic granulomas in the IL-6−/− mouse (e). (original magnification, a, ×400; b–e, ×100).

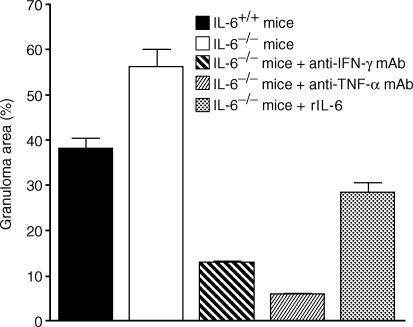

Figure 3.

Granuloma formation in the liver at 2 weeks p.i. The mean area of granulomas per field was determined in 10 optical fields of each section from livers of mice treated in the following ways: IL-6+/+ mice; IL-6−/− mice; IL-6−/− mice treated with anti-IFN-γ mAb; IL-6−/− mice treated with anti-TNF-α mAb; and IL-6−/− mice administered rIL-6.

Next, we examined the effects of administration of mAbs against IFN-γ and TNF-α on granuloma formation of R. aurantiacus-treated IL-6−/− mice. Endogenous IFN-γ or TNF-α produced by R. aurantiacus-injected IL-6−/− mice was neutralized by injection of an anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb or anti-mouse TNF-α mAb on day −1 before R. aurantiacus infection. The treatment with the anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb markedly reduced the number and size of granulomas in the tissues of IL-6−/− mice at 2 weeks p.i. (Figs 2c and 3). Few granulomas were apparent in the IL-6−/− mice treated with the anti-mouse TNF-α mAb at 2 weeks p.i. (Figs 2d and 3). Notably, no granulomas with central necrotic areas were observed in the slides from either IL-6−/− mice treated with the anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb or with anti-mouse TNF-α mAb (Fig. 2c, d). In a group of IL-6−/− mice treated prophylactically with rIL-6, granuloma size and the central necrotic area were substantially smaller than in IL-6−/− mice treated with PBS at 2 weeks p.i. (Figs 2e and 3).

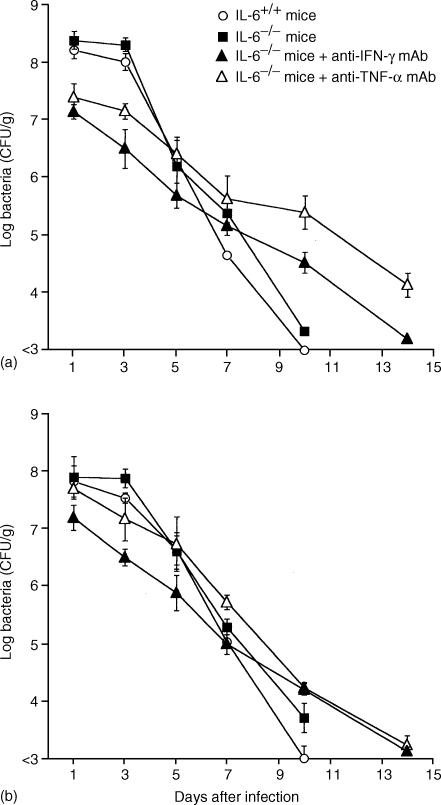

Survival of mice infected with R. aurantiacus and kinetics of bacterial growth

After IL-6−/− mice and IL-6+/+ mice were challenged with 108 CFU of R. aurantiacus, the bacterial loads in the spleen and liver were assessed. Bacterial counts in the spleen and liver in both IL-6−/− mice and IL-6+/+ mice markedly decreased and fell to an undetectable level by day 10 p.i., while bacteria were still detectable at 2 weeks p.i. in IL-6−/− mice treated with the anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb or anti-mouse TNF-α mAb (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Kinetics of bacterial number (Log CFU) of R. aurantiacus-infected IL-6+/+ mice, IL-6−/− mice, IL-6−/− mice treated with anti-IFN-γ mAb, and IL-6−/− mice treated with anti-TNF-α mAb. Four groups of mice were infected with 1 × 108 CFU of R. aurantiacus, and the numbers of viable bacteria present in spleens (a) and livers (b) were determined from days 1–14 p.i. Each point represents the mean ± SD of the R. aurantiacus CFU from 10 mice per time point.

Endogenous IFN-γ and TNF-α production

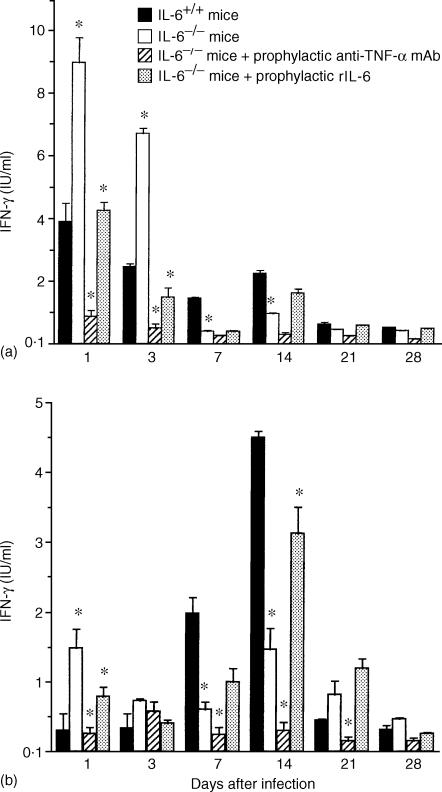

Titres of endogenous IFN-γ were determined in spleen and liver extracts by ELISA. In the IL-6+/+ mice infected with R. aurantiacus, production of IFN-γ was biphasic in the spleen, with an early phase detected at days 1 through 3 and a late phase detected at 2 weeks (Fig. 5a), while an elevated IFN-γ level was detected at 1 week p.i and peaked at 2 weeks p.i. in the liver (Fig. 5b). Infection of IL-6−/− mice with R. aurantiacus caused substantially greater production of IFN-γ in the spleen than seen in the IL-6+/+ mice at days 1 through 3, but not at 2 weeks p.i. (Fig. 5a). Similarly, a high level of IFN-γ was observed in the livers of IL-6−/− mice at day 1 p.i. (Fig. 5b) and in the in vitro cultures of splenocytes that were removed from IL-6−/− mice on day 1 p.i. (data not shown). Treatment with rIL-6 markedly decreased IFN-γ production in the early phase of the infection, while treatment with the anti-TNF-α mAb decreased endogenous IFN-γ titres throughout the period of infection in IL-6−/− mice (Fig. 5a, b).

Figure 5.

Endogenous IFN-γ production in spleen extracts (a) and liver extracts (b) of various mouse groups: infected IL-6+/+ mice, infected IL-6−/− mice, infected IL-6−/− mice treated prophylactically with anti-TNF-α mAb and infected IL-6−/− mice treated prophylactically with rIL-6. Compared with IL-6+/+ mice, a significantly higher level of IFN-γ is observed in the early phase of infection in IL-6−/− mice, whereas IFN-γ production shows a greater decrease at 2 weeks p.i. in IL-6−/− mice. Treatment with anti-TNF-α mAb prevented IFN-γ production. In the IL-6−/− mice treated with rIL-6, the production of IFN-γ in the early phase is observed to decrease. The data are the mean ± SD of 6 mice per group *P < 0·01.

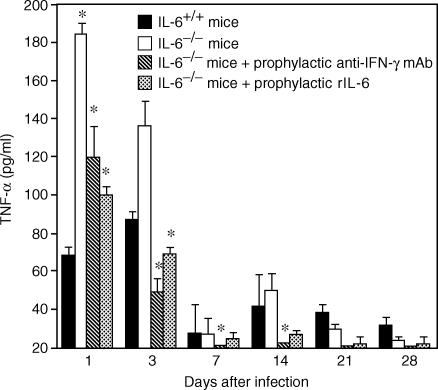

Endogenous TNF-α assay was also carried out on liver extracts. In the IL-6+/+ mice, the pattern of TNF-α secretion in the liver was similar to that of IFN-γ in the spleen, with an early phase detected at days 1 through 3 and a late phase detected from 1 week p.i and peaked at 2 weeks p.i. In contrast with the infected IL-6+/+ mice, a great excess of TNF-α was produced at days 1 through 3 p.i. in infected IL-6−/− mice. TNF-α production was suppressed by administration of a single injection of rIL-6 to IL-6−/− mice (Fig. 6). Treatment with the anti-IFN-γ mAb to deplete endogenous IFN-γ also resulted in decreased TNF-α production in the IL-6−/−mice (Fig. 6). Endogenous TNF-α production could not be detected in the spleen extracts.

Figure 6.

Endogenous TNF-α production in liver extracts of various mouse groups: infected IL-6+/+ mice, infected IL-6−/− mice, infected IL-6−/− mice treated prophylactically with anti-IFN-γ mAb and infected IL-6−/− mice treated prophylactically with rIL-6. Compared with IL-6+/+ mice, a significantly higher level of TNF-α is observed in the early phase of infection in IL-6−/− mice. Treatment with either anti-IFN-γ mAb or rIL-6 prevented TNF-α production. The data are the mean ± SD of 6 mice per group *P < 0·01.

Discussion

Our previous studies established that intravenous injection of R. aurantiacus into normal mice induced a granulomatous inflammation in the organs that resembled sarcoidosis.11,12 Because, in this murine model, IL-6 protein level was elevated in the early phase of the infection (Fig. 1), we wondered whether IL-6 was required for granuloma formation induced by R. aurantiacus. It is of interest to note that there was a significant difference in granuloma formation between IL-6+/+ mice and IL-6−/− mice. While challenge with R. aurantiacus induced formation of non-necrotic and epithelioid granulomas in the livers of the IL-6+/+ mice at 2 weeks p.i., the liver sections of R. aurantiacus-infected IL-6−/− mice showed many large granulomas characterized by central necrosis at 2 weeks p.i. (Fig. 2a, b). Compared to the IL-6+/+ mice, endogenous IFN-γ and TNF-α levels in the early phase of infection were remarkably high in IL-6−/− mice (Fig. 5a, b and Fig. 6). Our previous studies revealed that, in the infection of IL-6+/+ mice with R. aurantiacus, IFN-γ produced by natural killer (NK) cells in the early phase was crucial in inducing granuloma formation.11,17 Similarly, in severe combined immunodeficiency mice, Kaneko et al. also showed that granuloma formation was dependent on the presence of IFN-γ from NK cells and TNF-α from macrophages in response to M. avium.18 Although IFN-γ and TNF-α in the early phase of the infection are essential for inducing type 1 granuloma, overproduction of these cytokines up-regulates granulomatous inflammation and leads to liver injury. It was reported that increased and sustained production of TNF-α and IFN-γ elicited hepatic apoptosis in mice infected with Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) and hepatic necrosis in rats administered concanavalin A (Con A). Furthermore, an anti-TNF-α mAb or anti-IFN-γ mAb inhibited these phenomena.19,20 In the present study, the decreased levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α resulting from administration of an anti-IFN-γ mAb or anti-TNF-α mAb to IL-6−/− mice resulted in total ablation of the granuloma necrosis, and reduced the number and size of these granulomas in comparison to IL-6−/− mice receiving normal rat globulin (Fig. 2c, d). These results indicated that R. aurantiacus-induced granuloma formation was dependent on the presence of endogenous IFN-γ and TNF-α produced in the early phase, and that overproduction of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the IL-6−/− mice was responsible for the central necrosis of the granulomas. Because IFN-γ can stimulate the production of TNF-α from macrophages and act synergistically with TNF-α to induce granuloma formation,11,21,22 it is possible that neutralization of endogenous IFN-γ by anti-IFN-γ treatment might affect TNF-α production. On the other hand, TNF-α is required as a stimulatory factor with IL-12 for production of IFN-γ by NK cells, and neutralization of endogenous TNF-α by an anti-TNF-α antibody considerably reduced IFN-γ production.23,24 We observed that treatment with either the anti-IFN-γ mAb or anti-TNF-α mAb significantly decreased production of both cytokines (Fig. 5a, b, and Fig. 6).

Compared to infected IL-6+/+ mice, there was a marked decline in secretion of IFN-γ during the gramuloma formation phase in infected IL-6−/− mice (Fig. 5a, b). This IFN-γ production has been verified to originate from CD8+ T cells in the R. aurantiacus-infected IL-6+/+ mouse, and plays a role in the differentiation of macrophages to epithelioid cells.11,12 It has also been shown that IL-6 has an essential role in activating T cells to make IFN-γ.5,25 In this study, injection of rIL-6 into IL-6−/− mice at day −1 before infection increased the production of IFN-γ during the granuloma formation phase (Fig. 5a, b). Thus, it is thought that lack of IL-6 results in decreased T cell IFN-γ production during granuloma formation in IL-6−/− mice infected with R. aurantiacus.

To demonstrate that IL-6 deficiency results in significant increases in levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α, and in up-regulation of granulomatous inflammation in IL-6−/− mice, we analysed the effect of exogenous IL-6. It has been shown that Con A-induced hepatitis is almost completely controlled by rIL-6, and that rIL-6 exerts its protective effect through multiple mechanisms, including reduction of IFN-γ and TNF-α production.26 In our experiment model, when a single intravenous injection of rIL-6 was given to IL-6−/− mice one day prior to R. aurantiacus infection, there was decreased IFN-γ and TNF-α production in the early phase of infection (Fig. 5a, b and Fig. 6), and the size and necrotic area of granulomas were remarkably smaller than those of infected IL-6−/− mice at 2 weeks p.i. These results suggest that IL-6 has a suppressive function in R. aurantiacus-induced granuloma formation by reducing IFN-γ and TNF-α production in the early phase of infection. Thus, it is thought that IL-6, as an inflammatory cytokine, plays an important role in countering the effects of IFN-γ and TNF-α in R. aurantiacus-induced granuloma formation.

In addition, R. aurantiacus in the spleen and liver of either IL-6+/+ mice or IL-6−/− mice was eliminated to equivalent extents, but the treatment of IL-6−/− mice with the anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb or anti-mouse TNF-α mAb delayed the bacterial elimination (Fig. 4), suggesting that R. aurantiacus removal was dependent on the existence of IFN-γ and TNF-α, but not IL-6.

These data indicate that overproduction of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the case of a lack of IL-6 increase the severity of granuloma inflammation, resulting in a necrotic granuloma formation in R. aurantiacus-infected mice. In conclusion, it appears that, as a proinflammatory cytokine, IL-6 secreted in the extremely early phase of R. aurantiacus infection plays an important role in suppressing tissue injury induced by excess inflammatory reaction via reduction of overproduction of inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α.

References

- 1.Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, et al. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;368:339–42. doi: 10.1038/368339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Snick J. Interleukin-6: an overview. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:253–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelberg R, Castro AG, Pedrosa J, Minoprio P. Role of interleukin-6 in the induction of protective T cells during mycobacterial infections in mice. Immunol. 1994;82:361–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denis M, Gregg EO. Recombinant tumor necrosis factor-alpha decreases whereas recombinant interleukin-6 increases growth of a virulent strain of Mycobacterium avium in human macrophages. Immunol. 1990;71:139–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blum AM, Metwali A, Elliott D, Li J, Sandor M, Weinstock JV. IL-6-deficient mice form granulomas in murine Schistosomiasis that exhibit an altered B cell response. Cellular Immunol. 1998;188:64–72. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalrymple SA, Lucian LA, Slattery R, McNeil T, Aud DM, Fuchion S, Lee F, Murray R. Interleukin-6-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Listeria monocytogenes infection: Correlation with inefficient neutrophilia. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2262–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2262-2268.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chensue SW, Warmington KS, Ruth JH, Lincoln P, Kunkel SL. Cytokine function during mycobacterial and schistosomal antigen-induced pulmonary granuloma formation. J Immunol. 1995;154:5969–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chensue SW, Warmington KS, Ruth JH, Lukacs N, Kunkel SL. Mycobacterial and schistosomal antigen-elicited granuloma formation in IFN-γ and IL-4 knockout mice: analysis of local and regional cytokine and chemokine networks. J Immunol. 1997;159:3565–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon S, Keshav S, Stein M. BCG-induced granuloma formation in murine tissues. Immunobiol. 1994;191:369–77. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manca C, Tsenova LC, Barry CE, III, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 induces a more vigorous host response in vivo and in vitro, but is not more virulent than other clinical isolates. J Immunol. 1999;162:6740–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asano M, Nakane A, Minagawa T. Endogenous gamma interferon is essential in granuloma formation induced by glycolipid-containing mycolic acid in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2872–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2872-2878.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asano M, Nakane A, Kohanawa M, Minagawa T. Sequential involvement of NK cells and CD8+ T cells in granuloma formation of Rhodococcus aurantiacus-infected mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:499–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spitalny GL, Havell EA. Monoclonal antibody to murine gamma interferon inhibits lymphokine-induced antiviral and macrophage tumoricidal activities. J Exp Med. 1984;159:1560–5. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.5.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams JS, Roncarolo MG, Yssel H, Andersson U, Gleich GJ, Silver JE. Strategies of anti-cytokine monoclonal antibody development. immunoassay of IL-10 and IL-5 in clinical samples. Immunol Rev. 1992;127:5–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakane A, Minagawa M, Kohanawa M, Chen Y, Sato H, Moriyama M, Tsuruoka N. Interactions between endogenous gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor in host resistance against primary and secondary Listeria monocytogenes infections. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3331–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3331-3337.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakane A, Numata A, Minagawa T. Endogenous tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-6, and gamma interferon levels during Listeria monocytogenes infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1992;60:523–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.523-528.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yimin, Kohanawa M, Sato Y, Minagawa T. Role of T cells in granuloma formation induced by Rhodococcus aurantiacus is independent of their interferon-gamma production. J Med Microbiol. 2001;50:688–94. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-8-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko H, Yamada H, Mizuno S, Udagawa T, Kazumi Y, Sekikawa K, Sugawara I. Role of tumor necrosis factor-α in mycobacterium-induced granuloma formation in tumor necrosis factor-α-deficient mice. Laboratory Invest. 1999;79:379–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YL, Yu CK, Lei HY. Propionibacterium acnes induces acute TNFα-mediated apoptosis of hepatocytes followed by inflammatory T-cell-mediated granulomatous hepatitis in mice. J Biomed Sci. 1999;6:349–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02253524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Q, Batey R, Pang G, Russell A, Clancy R. IL-6, IFN-γ and TNF-α production by liver-associated T cells and acute liver injury in rats administered concanavalin A. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:542–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esparza I, Mannel D, Ruppel A, Falk W, Krammer PH. Interferon-γ and lymphotoxin or tumor necrosis factor act synergistically to induce macrophage killing of tumor cells and schistosomula of Schistosoma mansoni. J Exp Med. 1987;166:589–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith D, Hansch H, Bancroft G, Ehlers S. T-cell-independent granuloma formation in response to Mycobacterium avium: role of tumour necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ. Immunol. 1997;92:413–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter CA, Subauste CS, Van Cleave VH, Remington JS. Production of gamma interferon by natural killer cells from Toxoplasma gondii-infected SCID mice: Regulation by interleukin-10, interleukin-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2818–24. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2818-2824.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tripp CS, Wolf SF, Unanue ER. Interleukin 12 and tumor necrosis factor α are costimulators of interferon γ production by natural killer cells in severe combined immunodeficiency mice with listeriosis, and interleukin 10 is a physiologic antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3725–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, Simpson RJ, Cheers C. Role of IL-6 in activation of T cells for acquired cellular resistance to Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1994;152:5375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizuhara H, O'Neill E, Seki N, et al. T cell activation-associated hepatic injury: mediation by tumor necrosis factors and protection by interleukin 6. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1529–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]