Abstract

The alymphoplasia (aly) mutation of mice prevents the development of systemic lymph nodes and Peyer's patches. The mutant homozygotes (aly/aly) are partially deficient in both humoral and cell-mediated immune functions. In the present study, we show that adult worm expulsion was slightly delayed and that T helper 2 (Th2)-type responses were partially defective in aly/aly mice after infection with Trichinella spiralis. Male aly/aly and aly/+ mice (8-weeks old) were infected with 400 muscle larvae. There was no difference in worm recovery between the two groups on day 5. However, worm recovery in aly/aly mice was significantly higher than that in aly/+ mice on day 14. Mucosal mast cells increased in number and peaked 14 days after infection in aly/+ mice. aly/aly mice were deficient in their mucosal mast cell response through out the primary infection. To examine the existence of mast cell precursors, aly/aly mice were treated with recombinant interleukin-3 (rIL-3) before infection. The mast cell response was poorly induced in aly/aly mice treated with rIL-3. An immunoglobulin E (IgE) response was not detected in aly/aly mice during the course of infection. Serum IgG1 levels in aly/aly mice were significantly lower than that of aly/+. The serum IgG2a levels increased in both strains of mice. However, IgG2a production in aly/aly mice on day 14 was half as much as that in aly/+mice. Stimulation of splenic T cells in vitro with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) showed that spleen cells from aly/+ mice on day 5 produced more IL-4 than spleen cells from aly/aly mice. IL-4 production from aly/aly mice on day 14 was half that from aly/+ mice. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) was produced in both aly/aly and aly/+ mice on day 14. Proliferation assay showed that T cells of aly/aly mice responded poorly when cultured with antigen-presenting cells. These results suggest that aly gene is needed for the induction of protective immunity and Th2 responses in mice infected with T. spiralis.

Introduction

In addition to its role in barrier function and absorption of nutrients, the intestinal mucosa has a crucial role in regional immunologic function. Especially, the M cell and Peyer's patches have been shown to be significant in the induction of mucosal immunity against various antigens including viruses, bacteria, and protozoa.1 Miyawaki et al.2 described a new spontaneous autosomal recessive mutation in mice (aly/aly) that causes a systemic absence of lymph nodes and Peyer's patches (alymphoplasia). The mutant homozygotes were shown to be deficient in both humoral and cell-mediated immune functions. Mutant mice have reduced levels of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and severely depressed levels of IgG and IgA in their sera, although they have mature T and B cells as determined by their cell surface antigens. More recently, Shinkura et al.3 have demonstrated that alymphoplasia in aly/aly mice is caused by a point mutation in the gene encoding NF (nuclear factor)-κB-inducing kinase which is a central mediator of NF-κB activation in T and B lymphocytes.

We have shown that the phenotype of T helper cells conferring protection against Trichinella spiralis in rats is an OX8– OX22– (CD8– CD45RC–) subset and that it is produced on days 2–3 after infection in mesenteric lymphadenectomized rats and functions in the intestine.4 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that lymphocyte activation in the first 48 hr as measured by incorporation of 3H-TdR is restricted to the epithelium and lamina propria and does not occur in the Peyer's patches.5 Thus, it is possible that the site in which lymphocytes become activated might be the intestinal mucosa in rats infected with T. spiralis. We anticipated that the deficient development of Peyer's patches in aly/aly mice might help us define the role of the Peyer's patches more clearly. In the present study, we show that adult worm expulsion was delayed in alymphoplastic (aly/aly) mice and that the Th2-type response after infection was impaired more severely, when compared to heterozygote (aly/+) mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male 8-week-old inbred aly/aly and aly/+ mice were purchased from the CLEA Japan, Inc. (Osaka, Japan).2 Male 7-week-old outbred ddY mice were obtained from the Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan). They were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Institute for Laboratory Animals of Kochi Medical School. All animals were handled under the regulations for animal welfare of the school.

Parasite

The strain of T. spiralis was maintained in our laboratory by serial passage in ddY mice. This strain of the parasite was originally supplied by Professor N. Watanabe, Department of Tropical Medicine, Jikei University School of Medicine. The procedures used to isolate larvae to infect mice and to count intestinal worms were done according to the methods of Bell and McGregor.6 Briefly, eviscerated mouse carcasses were cut into pieces and then digested for 1 hr for infection, or overnight for counting muscle worm burden at 37° in a pepsin–HCl digestion fluid. To count intestinal worms, the small intestine was removed from mice, slit open longitudinally, and then incubated in a Petri dish containing saline for 4 hr at 37°. The worms that emerged were counted under a dissecting microscope.

Antigens

Muscle larvae of the parasite were obtained as above, homogenized by Polytron® (Kinematica AG, Switzerland) and sonicated on ice by a sonicator (Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan). The suspension was centrifuged at 435 000 g for 10 min (TL-100, Beckman Instruments Inc., Palo Alto, CA). The supernatant portions were stored at −30° until use.7

Cell culture medium

RPMI-1640 medium was supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 0·1 mm sodium pyruvate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), 100 IU/ml penicillin (Toyo Jouzo, Shizuoka, Japan), 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Meiji Seika Kaisha, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), 15 mm 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl] ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES), and 0·05 mm 2-mercaptoethanol (all from Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan).

Recombinant interleukin (IL)-3

rIL-3 was prepared from the culture supernatants of a myeloma cell line transfected with murine IL-3 cDNA, X63BMG 14-17.8

Preparation of spleen cells

Mice infected with T. spiralis were killed by bleeding under anaesthesia with diethylether and the spleen was removed aseptically and squeezed through a steel sieve using a silicone plug (Abe Kagaku Co., Chiba, Japan) into 15 ml of RPMI-1640 medium with 2% FBS and 30 mg/l DNase I (Sigma). After allowing the debris to settle, the cell suspension was transferred to a 15-ml centrifuge tube, then pelleted at 400 g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in 2 ml of Tris (2·05 g/l)-buffered ammonium chloride (7·5 g/l) for 2 min on ice to lyse erythrocytes, washed twice, resuspended in the culture medium, and counted in 0·1% trypan blue solution (Chroma Gesellscaft, Köngen, Germany).

Cell proliferation assay

Spleen cells were cultured in a Petri dish (Iwaki Glass Co., Tokyo, Japan) containing 5 ml cell culture medium with 10% FBS for 3–4 hr at 37°. After removing non-adherent cells, 5 ml of Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Ca2+, Mg2+ free) (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was added to the dish which was transferred to 4° for 30 min. Adherent cells were collected by pipetting and centrifuged. The pellet was resuspended with cell culture medium. The adherent cells were used as antigen-presenting cells. Cells (1 × 107) were incubated with 10 µg/ml of the antigen and 50 µg/ml of mitomycin C (Sigma) for 1 hr at 37°. After 4–5 washes, the cells were resuspended and adjusted in to 0·5 × 105/200 µl/well in 96-well culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark).

A T-enriched population was prepared with fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD11b (Mac 1), FITC-conjugated anti-CD45R (B220) (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and anti-FITC-magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The purity of the T cell population was >95%.7 Cells of the T-enriched population (2 × 105/200 µl/well) were incubated together with antigen-pulsed or non-pulsed adherent cells for 4 days at 37° in the CO2 incubator. The culture plate was centrifuged and the supernatant was removed. 100 µl of culture medium containing 10% TetraColor ONE® (2-(2-methoxy-4 nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulphophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, monosodium salt and 1-methoxy-5-methylphenazinium methylsulphate; Seikagaku Co., Tokyo, Japan) was added to each well. After incubation for 2 hr, absorbence values at 450/630 nm were recorded using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices Co., Sunnyvale, CA). The effectiveness of antigen presentation was calculated as followed; (absorbence of antigen-pulsed cells) − (absorbence of non-pulsed cells).

Detection of IL-4 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production in splenic T-cell culture by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Cytokine assays were performed as previously described.7 The T-enriched cell population was restimulated with anti-CD3 in vitro as follows: 6·5 × 105 cells/150 µl/well were cultured in 96-well flat-bottomed culture plates treated with anti-CD3 for 48 hr at 37° in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 (Astec, Fukuoka, Japan). In each experiment, duplicate cultures were established from four mice. At the end of incubation, cell supernatant portions were collected and frozen at −80° until they were tested. IL-4 or IFN-γ activity contained in the supernatant portions was measured by ELISA kits according to the manufacture's protocol (Bio Source International, Camarillo, CA).

ELISA for total serum IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a

For the measurement of total serum IgE, a sandwich ELISA was developed using two monoclonal rat anti-mouse IgE antibodies (mAb; 6HD5 and HMK-12) as mentioned previously.9 Briefly, coating of the wells of microtitration plate (MaxisorpTM, NUNC) was performed using 6HD5 (10 µg/ml) at 4° overnight. After blocking with bovine serum albumin (10 mg/ml) in PBS/Tween 20, serum samples and standard mouse IgE (SPE-7) were applied at 37° for 1 hr. After incubation, biotinylated-HMK-12 was used at a 1 : 3000 (v/v) dilution and then streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Germany) was applied at a 1 : 3000 (v/v) dilution. For colouring, 1,2-phenylenediamine substrate solution was added to the wells according to the manufacturer's method (Dako A/S, Denmark). The absorbence values were read by spectrophotometer at 490 nm.

Polyclonal IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies were detected by ELISA. Rabbit anti-mouse IgG1 or antimouse IgG2a (Dako) was coated at a dilution of 1 : 1000 (v/v) in the wells of microtitration plates. Serum samples and standard mouse IgG1 and IgG2a were optimally diluted and applied. Rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins bound to horseradish peroxidase were then applied at a dilution of 1 : 1000 (v/v).

Histology

A piece of the small intestines was fixed with Carnoy's fixative, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with 0·1% Alcian blue (Sigma) in 0·7 n HCl (pH 0·3) (room temperature, overnight) and 0·5% Safranin-O (Nacalai Tesque) in 0·125 n HCl (pH 1·0) as described previously.10 The number of intestinal mast cells in the epithelium and villous lamina propria were counted for 10 villus crypt units.

Statistical analysis

Probability of significant differences between groups was determined by Student's t-test. A value (P) less than 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of aly mutation on worm burdens and intestinal mucosal mast cell response

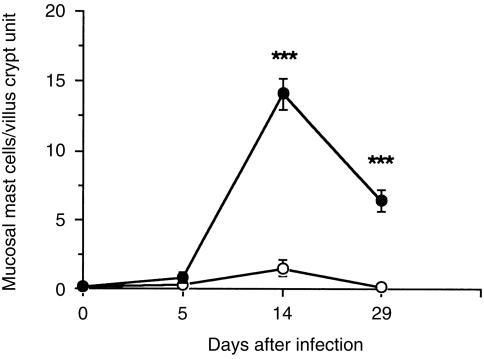

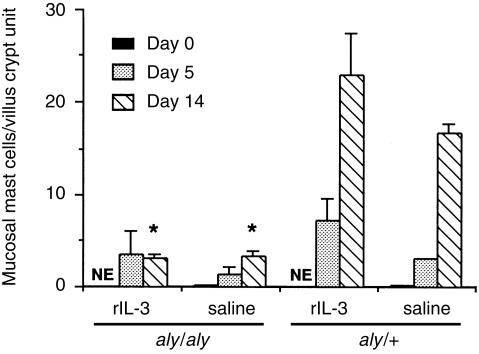

To examine the effect of aly mutation on the host's protective response, 400 muscle larvae were inoculated into both aly/aly and aly/+mice. Intestinal adult worms were expelled earlier in aly/+mice than in aly/aly mice (Table 1). Muscle worm burdens were not significantly different between two groups on day 30 (mean±se; 16 100 ± 1590 in aly/aly, 18 100 ± 2690 in aly/+). Mucosal mast cell numbers increased on day 14 after infection in aly/+mice, but few mast cells were observed in aly/aly mice (Fig. 1). The next experiment sought to establish the existence of mast cell progenitors in aly/aly mice. To do this, aly/aly mice were treated with rIL-3 for 5 days before infection, as shown in Fig. 2, mast cells were induced slightly in aly/aly mice treated with rIL-3, while bigger increase in the number of mast cells was observed in aly/+mice after the same treatment.

Table 1.

Number of worms* recovered from the small intestine in aly/aly and aly/+mice infected with 400 Trichinella spiralis muscle larvae

| Mice | Day 5 | Day 14 |

|---|---|---|

| aly/aly | 170 ± 14 | 77 ± 19† |

| aly/+ | 182 ± 14 | 18 ± 5 |

Mean ± se.

P < 0·05.

Figure 1.

Kinetics of mucosal mast cell responses in aly/aly and aly/+mice infected with Trichinella spiralis. Mice were infected with 400 muscle larvae. Values represent mean±se from four mice. (○) aly/aly; (•) aly/+. ***P < 0·001.

Figure 2.

Mucosal mast cell responses in aly/aly and aly/+mice treated with rIL-3 before infection with Trichinella spiralis. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with a total of 10 000 units rIL-3 or saline for 5 days before infection with 400 muscle larvae. Values represent means±se from three mice. NE; not examined. Significantly different from aly/+ values. *P < 0·05.

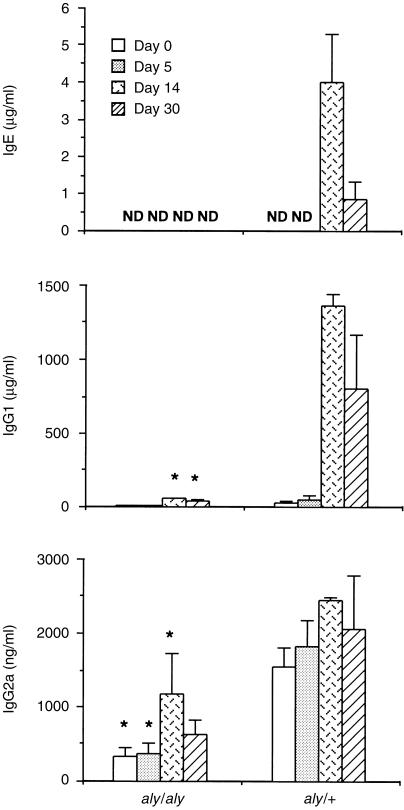

IgE, IgG1 and IgG2a responses during a primary infection

Mice were bled on days 0, 5, 14 and 30 after infection. Immunoglobulin levels were examined in serum by ELISA. IgE was undetectable in aly/aly mice during the course of infection. Low levels of IgG1 were detected in aly/aly mice on days 14 and 30. The IgG2a level in aly/aly mice was less than that in aly/+mice (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Immunoglobulin levels in aly/aly and aly/+mice infected with Trichinella spiralis. Total serum IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a levels were detected with ELISA. Values represent means±se from three to four mice. ND; not detected (IgE < 30 ng/ml, IgG1 < 2 µg/ml, IgG2a < 200 ng/ml). Significantly lower than aly/+ values. *P < 0·05.

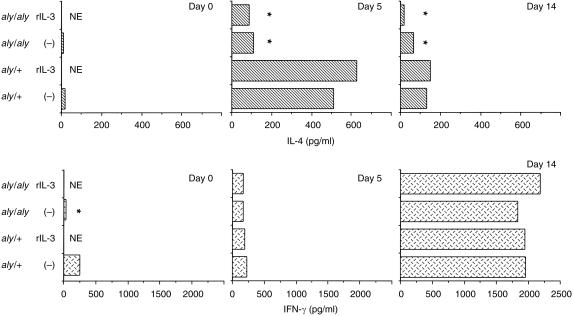

IL-4 and IFN-γ production in spleen cell cultures obtained from aly/aly and aly/+ mice

To compare the cytokine responses between aly/aly and aly/+mice infected with the parasite, mice were killed on days 0, 5, and 14 after infection. The supernatants of splenic T-cell-enriched cultures stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb were collected 48 hr later. IL-4 production from the aly/aly mice was significantly less than that from aly/+mice on day 5. rIL-3 treatment slightly affected IL-4 production of splenic T cells from aly/+mice on day 5. IFN-γ production was significantly different between the two groups of mice on day 0, but it was not different on days 5 and 14 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

IL-4 and IFN-γ production of splenic T cells from aly/aly and aly/+mice infected with Trichinella spiralis. Spleen cells were separated into subsets using mAb and magnetic beads. Pooled cells (6·5 × 105/150 µl/well) were cultured in 96-well plate with anti-CD3 mAb for 48 hr. Cytokines in the culture supernatant were detected by ELISA. Values represent means from duplicates. NE; not examined. Significantly different from aly/+ values. *P < 0·05.

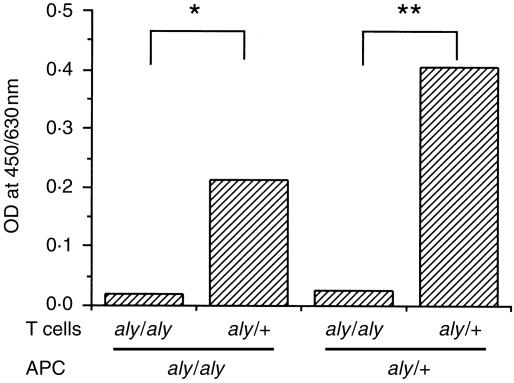

Splenic T-cell proliferation

To examine the proliferative response of T cells, spleen cells were separated from aly/aly and aly/+mice infected with T. spiralis on day 8. As shown in Fig. 5, T cells of aly/+mice proliferated, when cultured with macrophages from either aly/aly or aly/+mice but the proliferation of T cells from aly/aly mice was poor.

Figure 5.

Proliferation of splenic T cells cultured with antigen-presenting cells. aly/aly and aly/+mice were infected with Trichinella spiralis. The spleens were removed on day 8 after infection. After treatment with mitomycin C, 0·5 × 105/well plastic adherent cells were used as antigen-presenting cells. T-enriched cells were prepared with mAb and magnetic microbeads. Cells (2 × 105/200 µl/well) were cultured with antigen-pulsed or nonpulsed adherent cells for 4 days. Cell growth was measured with TetraColor ONE®. Values represent (absorbence of antigen-pulsed cells) − (absorbence of non-pulsed cells) from duplicates. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

Discussion

The present study showed that adult worm expulsion in mutant (aly/aly) mice was delayed and that the Th2 response was decreased in aly/aly mice. The results supported the involvement of Th2-type responses in protective immunity against T. spiralis. We have previously shown that rIL-3 treatment hastens not only worm expulsion but also Th2 type responses in C3H/He mice.7,9,10 Lawrence et al.11 have indicated that a novel interplay between IL-4 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) is involved in intestinal pathology in T. spiralis infection and that the IL-4-dependent protective response against the parasite operates by a mechanism other than the gross degradation of the parasite's environment brought about by the immune enteropathy. Furthermore, IL-4, IL-13, IL-4 receptor α-chain, and Stat6 have all been demonstrated to be important for protective immunity against the parasite.12 Although resistance to intestinal nematode infections is thought to correlate with the ability to mount a CD4+ Th2 type response, the actual effector mechanisms remain poorly defined.13

Our results in this study indicated that the gene aly was involved in regulation of intestinal immunity against T. spiralis infection in mice. Recently, Shinkura et al.3 have shown that the aly allele carries a point mutation causing an amino acid substitution in the carboxy-terminal interaction domain of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK). NIK is a central mediator of NF-κB activation in T and B cells. T cells are essential for induction of worm expulsion and pathology during the course of infection with T. spiralis.14–16 In the present study, we showed that T cell proliferation from aly/aly mice was poor after in vitro stimulation with the antigens. Furthermore, Th2-type responses were depressed in T. spiralis infected-aly/aly mice, while Th1-type responses were not so. Interestingly, in Listeria monocytogenes infection, the production of IFN-γ, IL-4 and TNF-α has been reported to be diminished in the spleen cell cultures of aly/aly mice.17 Although it is unclear how the host's response against different pathogens is differentially regulated, the present results suggest a possibility that NIK-independent mechanism(s) might induce Th1-type responses in T. spiralis infection. Our results showed also an increased response of IFN-γ on day 14. It has been reported that IFN-γ production is detected on days 10–15 much higher than on days 3–9 in T. spiralis-infected mice.7,18,19 There is no report indicating how Th1 responses are regulated in intestinal helminth infection.

In the present study, the generation of protective immunity against T. spiralis was deferred in aly/aly mice. In general, the Peyer's patches play an important role in T- and B-cell responses of gut-associated lymphoid tissue.20,21 Secondary lymphoid organs (the spleen, lymph nodes and mucosal lymphoid tissues) are thought to provide the proper environment for antigen-presenting cells to interact with and activate naive T and B cells. In T. spiralis infection, a mesenteric node response, characterized by increased cellularity22 and large numbers of dividing cells, peaked on day 8 in NIH mice.23 In mice, protective helper T cells have been demonstrated in the mesenteric lymph node (MLN) from days 4–8·23,24 However, these facts do not directly indicate that the sites of T-cell activation are MLN in mice infected with the parasite. The observations in rats infected with T. spiralis have been reported to be more consistent with the direct activation of epithelial and lamina propria lymphocytes than they are of MLN or Peyer's patch cells.4,5,25 Recent evidence suggests that the capacity to generate an early humoral immunity against T. spiralis appears first in the non-Peyer's patch region of the small intestine.26 Furthermore, Yamamoto et al.27 have demonstrated that organized Peyer's patches are not a strict requirement for induction of mucosal IgA antibody responses in the gut. It is increasingly evident that intestinal epithelial cells participate, both directly and indirectly, in regulating local immunological functions of intraepithelial lymphocytes and the subjacent lymphocytes and mononuclear cells contained within the lamina propria.1 Using an in vitro model of epithelial invasion by T. spiralis, Li et al.28 have shown induction and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in epithelial cells that initiate the acute inflammatory response of the small intestine. Taken together, co-operation of both the epithelial cell and Peyer's patch region might be necessary to effectively generate protective immunity against T. spiralis in mice. To clarify more clearly the role of the Peyer's patches and MLN in mucosal immunity, it might be advantageous to use gene-targeted mice that have abnormality in lymphoid organogenesis. Lymphotoxin (LT)-β-deficient mice29 lack the Peyer's patches, peripheral lymph nodes, but that have cervical lymph nodes and MLN unlike LT-α-deficient mice.30,31 In contrast to Peyer's patches, peripheral lymph nodes and MLN are present in p55 TNF receptor-deficient mice.32 Furthermore, TNF-α has been demonstrated to be a critical factor of IL-13-mediated protective responses in mice infected with Trichuris muris.33 In this context, the role of TNF-α and/or secondary lymphoid organs in mucosal immunity should be examined.

In the present study, mucosal mast cells were slightly induced in aly/aly mice treated with rIL-3. This might be due to a poor IL-4 response in aly/aly mice after infection with T. spiralis, but not to the absence of the progenitors. IL-4 is thought to be one physiologically important stimulus of mastocytosis in vivo.34 The results in the present study could not exclude the possibility that mast cells in aly/aly mice have a defect in the ability to migrate to the intestine. Our results support the hypothesis that mastocytosis is involved in adult worm expulsion in mice infected with T. spiralis. Prolongation of T. spiralis infection has been reported in mast-cell-deficient W/WV mice35–37 and in mice treated with anti-stem cell factor and/or anti-c-kit mAb.38,39 It has been demonstrated that systemic and intestinal release of intestinal mast cell proteinase coincides with the immune expulsion of adult worms from the intestine in T. spiralis infection.40,41

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Professor R. G. Bell, Cornell University, for valuable discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Professors T. Abe, Akita Prefectural University, and N. Watanabe, Jikei University School of Medicine for their provision of cytokine and monoclonal antibodies. We also wish to thank Mrs. K. Imamura for assisting in continued studies. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 10670230) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture in Japan, and the president research fund of Kochi Medical School. A part of this study was presented at 10th International Conference on Trichinellosis.

References

- 1.Mayer L, Blumberg RS. Antigen-presenting cells: Epithelial cells. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, Bienenstock J, McGhee JR, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 365–79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyawaki S, Nakamura Y, Suzuka H, Koba M, Yasuzumi R, Ikehara S, Shibata Y. A new mutation, aly, that induces a generalized lack of lymph nodes accompanied by immunodeficiency in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:429–34. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shinkura R, Kitada K, Matsuda F, et al. Alympholasia is caused by a point mutation in the mouse gene encoding NF-κB-inducing kinase. Nat Genet. 1999;22:74–7. doi: 10.1038/8780. 10.1038/8780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korenaga M, Wang CH, Bell RG, Zhu D, Ahmad A. Intestinal immunity to Trichinella spiralis is a property of OX8– OX22– T-helper cells that are generated in the intestine. Immunology. 1989;66:588–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang CH, Korenaga M, Sacuto FR, Ahmad A, Bell R. Intraintestinal migration to the epithelium of protective, dividing, anti-Trichinella spiralis CD4+ OX22– cells requires MHC class II compatibility. J Immunol. 1990;145:1021–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell RG, McGregor DD. Requirement for two discrete stimuli for induction of the intestinal rapid expulsion response against Trichinella spiralis in rats. Infect Immun. 1980;29:186–93. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.1.186-193.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korenaga M, Akimaru Y, Hashiguchi Y. Exogenous interleukin-3 enhances IL-4 production by splenic CD4+ cells during the early stages of a Trichinella spiralis infection. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998;117:131–7. doi: 10.1159/000024000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karasuyama H, Melchers F. Establishment of mouse cell lines which constitutively secrete large quantities of interleukin 2, 3, 4 or 5, using modified cDNA expression vectors. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:97–104. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korenaga M, Watanabe N, Abe T, Hashiguchi Y. Acceleration of IgE responses by treatment with recombinant interleukin-3 prior to infection with Trichinella spiralis in mice. Immunology. 1996;87:642–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.505586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korenaga M, Abe T, Hashiguchi Y. Injection of recombinant interleukin 3 hastens worm expulsion in mice infected with Trichinella spiralis. Parasitol Res. 1996;82:108–13. doi: 10.1007/s004360050079. 10.1007/s004360050079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawrence CE, Paterson JCM, Higgins LM, MacDonald TT, Kennedy MW, Garside P. IL-4-regulated enteropathy in an intestinal nematode infection. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2672–84. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2672::AID-IMMU2672>3.0.CO;2-F. 10.1002/(sici)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2672::aid-immu2672>3.3.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urban JF, Jr, Schopf L, Morris SC, et al. Stat6 signaling promotes protective immunity against Trichinella spiralis through a mast cell- and T cell-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2000;164:2046–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Else KJ, Finkelman FD. Intestinal nematode parasites, cytokines and effector mechanisms. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:1145–58. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(98)00087-3. 10.1016/s0020-7519(98)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walls RS, Carter RL, Leuchars E, Davies AJS. The immunopathology of trichiniasis in T-cell deficient mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;13:231–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruitenberg EJ, Steerenberg PA. Intestinal phase of Trichinella spiralis in congenitally athymic (nude) mice. J Parasitol. 1974;60:1056–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruitenberg EJ, Elgersma A, Kruizinga W, Leenstra F. Trichinella spiralis infection in congenitally athymic (nude) mice: parasitological, serological and haematological studies with observations on intestinal pathology. Immunology. 1977;33:581–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishikawa S, Nakane A. Host resistance against Listeria monocytogenes is reciprocal during the course of infection in alymphoplastic aly mutant mice. Cell Immunol. 1998;187:88–94. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1329. 10.1006/cimm.1998.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grencis RK, Hultner L, Else KJ. Host protective immunity to Trichinella spiralis in mice: activation Th cell subsets and lymphokine secretion in mice expressing different phenotypes. Immunology. 1991;74:329–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pond L, Wassom DL, Hayes CE. Influence of resistant and susceptible genotype, IL-1, and lymphoid organ on Trichinella spiralis-induced cytokine secretion. J Immunol. 1992;149:957–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelsall B, Strober W. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue: Antigen handling and T-lymphocyte responses. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, Bienenstock J, McGhee JR, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 365–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGhee JR, Lamm ME, Strober W. Mucosal immune responses, an overview. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, Bienenstock J, McGhee JR, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 485–506. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manson-Smith DF, Bruce RG, Rose ML, Parrott DMV. Migration of lymphoblasts to the small intestine: III. Strain differences and relationship to distribution and duration of Trichinella spiralis infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1979;38:475–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grencis RK, Wakelin D. Short lived, dividing cells mediate adoptive transfer of immunity to Trichinella spiralis in mice: I. Availability of cells in primary and secondary infections in relation to cellular changes in the mesenteric lymph node. Immunology. 1982;46:443–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grencis RK, Riedlinger J, Wakelin D. L3T4-positive T lymphoblasts are responsible for transfer of immunity to Trichinella spiralis in mice. Immunology. 1985;56:213–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bell RG, Korenaga M, Wang CH. Characterization of a cell population in thoracic duct lymph that adoptively transfers rejection of adult Trichinella spiralis to normal rats. Immunology. 1987;61:221–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang CH, Richards EM, Block RD, Lezcano EM, Gutierrez R. Early induction and augmentation of parasitic antigen-specific antibody-producing B lymphocytes in the non-Peyer's patch region of the small intestine. Front Bioscience. 1998;3:A58–65. doi: 10.2741/a253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto M, Rennert P, McGhee JR, et al. Alternate mucosal immune system: organized Peyer's patches are not required for IgA responses in the gastrointestinal tract. J Immunol. 2000;164:5184–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li CKF, Seth R, Gray T, Bayston R, Mahida YR, Wakelin D. Production of proinflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators in human intestinal epithelial cells after invasion by Trichinella spiralis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2200–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2200-2206.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koni PA, Sacca R, Lawton P, Browning JL, Ruddle NH, Flavell RA. Distinct roles in lymphoid organogenesis for lymphotoxins α and β revealed in lymphotoxin β-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Togni P, Goellner J, Ruddle NH, Streeter PR, et al. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science. 1994;264:703–7. doi: 10.1126/science.8171322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banks TA, Rouse BT, Kerley MK, et al. Lymphotoxin-α-deficient mice: Effects on secondary lymphoid organ development and humoral immune responsiveness. J Immunol. 1995;155:1685–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumann B, Luz A, Pfeffer K, Holzmann B. Defective Peyer's patch organogenesis in mice lacking the 55-kD receptor for tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med. 1996;184:259–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Artis D, Humphreys NE, Bancroft AJ, Rothwell NJ, Potten CS, Greenish RK. Tumor necrosis factor α is a critical component of interleukin 13-mediated protective T helper cell type 2 responses during helminth infection. J Exp Med. 1999;190:953–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madden KB, Urban JF, Jr, Ziltener HJ, Schrader JW, Finkelman FD, Katona IM. Antibodies to IL-3 and IL-4 suppress helminth-induced intestinal mastocytosis. J Immunol. 1991;147:1387–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ha TY, Reed ND, Crowle PK. Delayed expulsion of adult Trichinella spiralis by mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice. Infect Immun. 1983;41:445–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.1.445-447.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alizadeh H, Murrell KD. The intestinal mast cell response to Trichinella spiralis infection in mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice. J Parasitol. 1984;70:767–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oku Y, Itayama H, Kamiya M. Expulsion of Trichinella spiralis from the intestine of W/WV mice reconstituted with haematopoietic and lymphopoietic cells and origin of mucosal mast cells. Immunology. 1984;53:337–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grencis RK, Else KJ, Huntley JF, Nishikawa SI. The in vivo role of stem cell factor (c-kit ligand) on mastocytosis and host protective immunity to the intestinal nematode Trichinella spiralis in mice. Parasite Immun. 1993;15:55–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1993.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donaldson LE, Schmitt E, Huntley JF, Newlands GFJ, Grencis RK. A critical role for stem cell factor and c-kit in host protective immunity to an intestinal helminth. Int Immunol. 1996;8:559–67. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huntley JF, Gooden C, Newlands GFJ, et al. Distribution of intestinal mast cell proteinase in blood and tissues of normal and Trichinella-infected mice. Parasite Immun. 1990;12:85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1990.tb00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuohy M, Lammas DA, Wakelin D, Huntley JF, Newlands GFJ, Miller HRP. Functional correlations between mucosal mast cell activity and immunity to Trichinella spiralis in high and low responder mice. Parasite Immun. 1990;12:675–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1990.tb00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]