Abstract

Mouse, human and rat mast cells have been shown to express major histocompatibility complex II molecules and present antigens to specific T-cell hybridomas in vitro. The purpose of our investigation was to determine whether mouse mast cells are able to initiate specific immune responses in vivo. Induction of anti-dinitrophenyl (DNP) immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2a antibodies was performed by transferring ovalbumin (OVA)–DNP-pulsed bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMC), B cells, or macrophages into naive mice which were boosted later with soluble antigen. Cultured spleen cells from immunized mice were tested for their cytokine content. Our data show that mast cells were by far better inducers of anti-DNP IgG1 antibodies than were B cells and macrophages. In contrast, anti-DNP IgG2a response induced by macrophages was much stronger than that obtained with mast cells whereas B cells were completely unable to elicit this response. In addition to a high index of cell proliferation, spleen cells from mast cell-injected mice produced more interferon-γ than those mice who received macrophages or B cells by two- to fivefold, and almost 10-fold, respectively. Mast cell-deficient Wf/Wf mice were compared with their normal +/+ littermates and with mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice to develop delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reactions as well as humoral immune responses. Mast cell sufficient mice as well as mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice developed significantly increased DTH reactions (P = 0·02, and 0·03, repectively) and higher anti-OVA-specific antibody responses as compared with Wf/Wf mice. Our data suggest that mast cells have the potential to up-regulate both humoral and cellular immune responses in vivo.

Introduction

Until recently mast cells have been almost exclusively shown to be critical effector cells in immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated allergic responses. In this context, the common evolutionary view on the determinism of mast cells is their potential to cause tissue damage to the host. This deleterious effect has been recently tempered by several reports that ascribe to mast cells potential roles in the expression of specific1 as well as innate immune responses.2–5 Mouse,6,7 rat8 and human mast cells9,10 have been shown to express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and induce antigen-specific T-cell activation in vitro. In addition, it has been demonstrated that mast cells, like other professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), express adhesion11 as well as co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86.12 A series of reports have elegantly demonstrated that mast cells are critical components of innate immunity and that they contribute to the initiation and the amplification of host defence mechanisms against bacterial infections. Mast cell-deficient mice, infected with a virulent strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae were much less efficient in clearing bacteria than their normal littermates or mast cell-reconstituted deficient mice.4 Similar findings were obtained in a model of acute septic peritonitis where mast cell-deficient mice showed increased mortality as compared to normal mice or to mast cell-deficient mice reconstituted with mast cells.3

Various strategies can be used to investigate the contribution of a particular APC to the immune response in vivo. For instance, studies on the B-cell APC function demonstrated that the transfer into mice of rat IgG targeted to B lymphocytes through IgM or IgD resulted in a specific IgG1 response.13 The failure of anti-IgM-treated mice to mount antigen-specific T-cell responses in lymph nodes demonstrates the role of B cells in the initiation of specific immune responses in vivo.14 More recently, by using mice transgenic for hen egg lysozyme (HEL)-specific IgM and IgD expressed in B cells, it was found that antigen-specific B cells induced maximal T-cell proliferation and significantly more interleukin-4 (IL-4) in comparison with polyclonal non-specific B cells and macrophages.15

Although mast cells have been shown to present antigens to T cells in vitro, no study has so far attempted to address the question of whether mast cells can act as APC in vivo and their relative potency as compared to ‘professional’ APC. In the experiments described herein we have assessed the role of mast cells as APCs in vivo by adoptively transferring antigen-pulsed bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMC) into naive mice and examining their ability to prime T cells. Our results demonstrate that mast cells were able to prime T cells in vivo for efficient T-cell as well as antibody responses to specific antigens. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the immune response promoted by different APCs indicate that the position of mast cells is intermediate between B cells and macrophages.

Materials and methods

Animals

Female BALB/c mice, 6–8-week-old and 4-month-old Lewis rats were purchased from Janvier (Laval, France). C3H/HeJ and Kit W/Kit Wf mice with a C3H genetic background were from the animal facility at the Institut Pasteur (Paris, France).

Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant mouse IL-3 and IL-4 were purchased from Immugenex (Los Angeles, CA). Ovalbumin (OVA) grade VII and dinitrophenyl–human serum albumin (DNP-HSA) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). 2,4-dinitrobenzenesulphonic (DNBS) acid was purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Coupling of DNP to OVA was prepared as follows: briefly, 2 mg of antigen were allowed to react with 2 mg of DNBS in a total volume of 2 ml of 0·2 m Na2CO3 at room temperature for 5 hr. The uncoupled hapten was removed by extensive dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Anti-mouse CD4 was prepared from GK1.5 clone (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD). Anti-Thy-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb; clone 9.37) was kindly provided by U. Hämmerling (Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York). Unlabelled anti-interferon-γ (IFN-γ; clone AN18), biotinylated anti-IFN-γ (clone R46A2), and anti-IL-4 mAbs (clones 11B11 and BVD6) were purchased from Pharmingen (San Francisco, CA). Anti-IL-5 (clone TRFK5), and biotinylated anti-IL-5 (TRFK4) were purshased from R & D Systems (Abingdon, UK).

Preparation of mast cells

BMMC were prepared as described elsewhere16 with slight modification by us.17 Briefly, bone marrow cells incubated for 7 days in RPMI-1640 culture medium containing 3 U/ml of recombinant IL-3 (rIL-3) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; ATGC, Noisy-Le Grand, France). Cells were passaged into the same medium every week until day 21. Mast cells were cultured in the presence of 100 U/ml rIL-4 and 3 U/ml of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for the last 48 hr. On day 21, the cells were harvested and thoroughly washed before their transfer into mice. Cultures consisted of over 98% mast cells as assessed by toluidine blue staining as well as by positive labelling with anti-CD117 antibody (clone ACK2).18 Consistent with our previous reports, non-specific esterase staining, immunofluorescence staining for Mac-1, NLDC-145, and B220 cell surface antigen indicated that mast cell preparations were not contaminated with macrophages, dendritic cells, or B cells, respectively.

Determination of mast cell number

A piece of dorsal skin or duodenum was gently flattened onto a piece of thick paper to avoid curling and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hr. Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and serial sections (5-µm thick sections) were deparaffinized in xylene, through ethanol to PBS pH 7·2. Slides were then stained with toluidine blue (2% toluidine blue in 0·7 m HCl pH 2·5) for 2 min. For each sample, measurements were made on five separate histological sections and the number of mast cells per centimetre length of tissue was determined. Measurements were obtained from 10 different +/+ or Wf/Wf mice.

Reconstitution of mast cell-deficient mice was carried out by injecting Wf/Wf mice intraperitoneally with 107 BMMC of syngeneic normal mice at 4 weeks of age. Complete reconstitution as assessed by the presence of mature mast cells in the peritoneal cavity and in the skin of Wf/Wf mice (data not shown) occurred 10 weeks following mast cell injections.

Preparation of B cells and macrophages

B cells were prepared by suspending spleen cells at 5 × 107/ml in the presence of anti-Thy-1 and anti-CD4 antibodies. After 30 min of incubation in ice, the cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1/10 dilution of fresh low-tox rabbit serum complement (Cedarlane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada), and incubated for 45 min at 37°. The complement lysis of T cells was repeated twice. The purity of B cells was consistently more than 95–98% as assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis using anti-B220 mAb.

Macrophages were obtained by in vitro differentiation of bone marrow precursor cells as described elsewhere19,20 in RPMI-1640 (Gibco–BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% FCS and 10% NCTC clone 929 fibroblast-conditioned medium. After 5 days of culture, macrophages were detached from bacteriological plastic Petri dishes (Sterilin, Staffordshire, UK) by incubating cells in trypsin solution for 1 min on ice immediately followed by extensive washes with 10% FCS-containing medium. Adherent cells which consisted of 90–95% of macrophages did express MHC II molecules but at a reduced level. To induce higher expression of MHC class II molecules, macrophage preparation was incubated for 24 hr with 25 U/ml murine rIFN-γ.

Immunization protocol

For priming T cells in vivo, mice received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 107 OVA–DNP-pulsed mast cells, B cells, or macrophages. Cells (2 × 106 in 0·5 ml of RPMI-1640) were incubated for 1 hr at 37° with 10 µg of OVA–DNP and after extensive washings were transferred into recipient mice. Control mice received unpulsed APCs or were left untreated. Mice were boosted twice, at days 5 and 20, with two i.p. injections of 100 µg of soluble OVA–DNP in the absence of any adjuvant. Control groups received 100 µg of OVA–DNP adsorbed on alum and were boosted 2 weeks later with the same amounts of OVA–DNP adsorbed on alum. Mice were bled at day 20 (primary response) and day 27 (secondary response).

T-cell proliferation assay

The T-cell proliferation assay was carried out in flat-bottom 96-well plates (Gibco) using RPMI-1640 supplemented with 5% (v/v) FCS (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), 5 × 10−5 m 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mm l-glutamine, 0·1 mm non-essential amino acids (Flow Laboratories, Rickmansworth, UK), penicillin 100 U/ml and streptomycin 0·1 mg/ml (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France). In a final volume of 200 µl/well, spleen cells (4 × 106/ml) were incubated in the presence of various antigen concentrations. After 48 hr of incubation, cultures were pulsed with 0·25 µCi [3H]TdR (Amersham, UK), and harvested 16 hr later. Means of duplicate thymidine incorporation obtained with the optimal OVA concentration of 10 µg/ml were represented.

Delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction

Ovalbumin (50 µg) in 25 µl of saline was emulsified with an equal volume of complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA; Sigma, St Louis, MO), and injected subcutaneously in both sides of the base of the tail. Delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) reactions were elicited in groups of five mice 7 days after the immunization by challenging mice with 30 µl at 1 mg/ml of aggregated OVA injected subcutaneously in the left hind footpad while the right hind footpad was injected with the same volume of saline. Footpad thickness was measured at 24 hr after challenge using a skin-thickness gauge. The extent of swelling was measured by subtracting values for saline-injected footpads from those for antigen-injected footpads. To assess whether aggregated OVA has any irritant effect, OVA-challenged footpads were compared to saline-challenged footpads of naive mice and no difference was observed. Aggregated OVA was prepared by heating a 2% solution of OVA at 70° for 1 hr. After cooling, the precipitate was washed and resuspended in the original volume of saline.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Flat-bottom 96-well plates (Nunc, Copenhagen, Denmark) were coated for 2 hr at 37° with anti-IL-4 mAb 11B11, anti-IL-5 TRFK5, or with anti-IFN-γ mAb AN18 at 4 µg/ml, 1 µg/ml, or 3 µg/ml, respectively. Some plates were coated with 3 µg/ml of DNP–bovine serum albumin (BSA). After three washes in PBS–Tween (0·1%) plates were saturated for 1 hr at 37° with PBS–BSA (0·1%). After three washes, standards and pure samples were incubated overnight at 4°. Plates were then incubated for 2 hr at 37° with 1 µg/ml of biotinylated anti-IL-4 BVD6 or with biotinylated anti-IL-5 TRFK4 with biotinylated anti-IFN-γ R46A2 mAbs at 1 µg/ml, 10 µg/ml, and 1 µg/ml, respectively. After washing, streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate was added for 2 hr at 37° followed by O-phenylenediamine (Sigma). Absorbance was determined by optical density at 490 nm. Anti-DNP antibodies were assessed by coating plates with DNP–HSA (3 µg/ml) followed by sera from immunized mice added at various dilutions. After 2 hr of incubation at 37°, plates were thoroughly washed and incubated with either peroxidase-labelled rabbit anti-mouse IgG1 or anti-mouse IgG2a antibodies (Burlingame, CA). Two hours later, plates were washed and the substrate O-phenylenediamine (Sigma) was added at a concentration of 1 mg/ml and the reaction was stopped by adding 1 m HCl. Optical density was read at 490 nm with an automated ELISA reader (Dynatech, Guernsey).

Induction of IgE response in vivo and analysis by passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) reaction

OVA-specific IgE antibodies were induced by injecting mice i.p. with 10 µg of OVA (Sigma) adsorbed on 0·2 ml of Al(OH)3 (alum) at 5 mg/ml. Serum IgE antibodies were detected by the PCA reaction in rats.21 Lewis rats received intradermal injections of serial dilutions of mouse sera and 4 hr later an intravenous challenge of Evans blue dye with 2 mg of OVA. PCA titre represents the highest dilution yielding a 5-mm blue spot.

Statistical analysis

Each group consisted of five mice and experiments were performed two or three times. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare the mean values between different groups and the significance was set up at P-values < 0·05.

Results

Mast cells pulsed with antigen induce antibody response in vivo

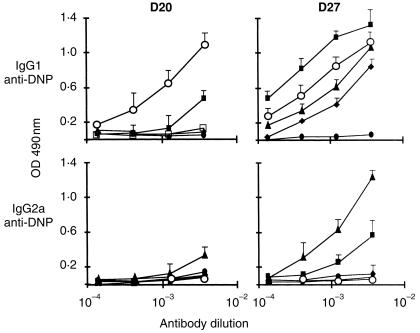

To demonstrate whether mast cells can prime immune cells for antibody response in vivo, BALB/c mice received 107 mast cells pulsed or not with OVA–DNP for 3 hr and were challenged 5 days and 20 days later with soluble OVA–DNP without any adjuvant. One week later, collected sera were analysed for their anti-DNP antibody content. Figure 1 shows that in vivo administration of DNP–OVA-pulsed mast cells induced specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies upon antigen challenge. Mice which received unpulsed mast cells or antigen alone did not mount any specific antibody response.

Figure 1.

Antigen-pulsed mast cells induce an antibody response in vivo. OVA–DNP-pulsed (▪) or unpulsed mast cells (□) (107/mouse) were intraperitoneally transferred into mice (five mice per group). Five and 20 days later, mice were given 100 µg of OVA–DNP in saline. Control mice received two shots of OVA–DNP at day 5 and 20 (•) or saline alone (○). Mice were bled 7 days after the last boost and sera were analysed for their anti-DNP IgG1 and IgG2a contents by ELISA. Values are expressed as means ± SEM of two separate experiments.

Comparative antibody response induced by mast cells, B cells and macrophages

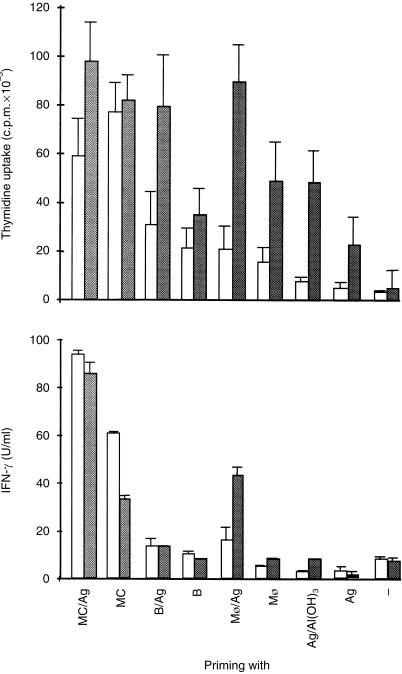

To assess the relative capacity of mast cells as compared to ‘professional’ APCs to initiate immune responses in vivo, BALB/c mice were primed with DNP–OVA-pulsed mast cells, B cells, or macrophages. Control groups received unpulsed APCs (not shown), the antigen alone, or alum-adsorbed OVA–DNP. All mice primed with cells were challenged 5 and 20 days later with soluble OVA–DNP in the absence of classical adjuvants. Figure 2 (left panels) shows that the primary anti-DNP IgG1 response was induced only by mast cells and alum whereas no response was obtained with macrophages and B cells. Conversely, the anti-DNP IgG2a was induced only by macrophages whereas no detectable response was found in mice injected with other APCs, or with alum. Interestingly, mast cells were found to be the most effective inducers of the secondary anti-DNP IgG1 response in comparison with macrophages and B cells (P < 0·01) and even with alum (P < 0·05) (Fig. 2, right panels). Although less effective than macrophages, this potent mast cell APC function applied also for the secondary anti-DNP IgG2a response which remained undetectable with alum and when B cells were used as APCs. The complete picture of the isotype analysis must include the IgE response, unfortunately in our system no anti-DNP IgE antibody production could be detected.

Figure 2.

Relative potency of mast cells, B cells and macrophages in inducing antibody responses in vivo. Immunization protocol was performed as in Fig. 1, except that in addition to those mice which received OVA–DNP-pulsed mast cells (▪), additional groups of mice were primed with OVA–DNP-pulsed B cells (♦) or macrophages (▴). Control groups of mice received at day 5 and 20 OVA–DNP alone (•) or alum-adsorbed OVA–DNP (○). Primary (D20) (left panels) and secondary (D27) (right panels) anti-DNP IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies were titrated by ELISA. Results are presented as means ± SEM from two separate experiments where each group consisted of five mice.

Effect of the in vivo priming with different APCs on the proliferative response and cytokine production

Secondary cell proliferative response to OVA was measured by incubating spleen cells from mice primed in vivo with OVA–DNP-pulsed or unpulsed mast cells, B cells, or macrophages, and immunized with soluble OVA–DNP according to the protocol described above, in the presence or in the absence of OVA. As shown in Fig. 3 (right panel), spleen cells from antigen-pulsed APCs and challenged in vitro with OVA all gave high proliferative responses. The most striking observation was that spleen cells from mice injected either with antigen-pulsed or unpulsed mast cells displayed a strong proliferative response whether they have been challenged or not with OVA in vitro. This non-specific mast cell-induced proliferative response was much more limited when B cells or macrophages were used as APCs. In parallel to the proliferative response, Fig. 3 (left panel) shows that large amounts of IFN-γ were found in every condition where mast cells were involved. Although non-specific IFN-γ production is a characteristic feature of mast cells, the largest IFN-γ production was induced in mice which received antigen-pulsed mast cells. While unpulsed B cells and macrophages did not induce significant amounts of IFN-γ, only antigen-pulsed macrophages gave significant and specific IFN-γ production. IL-4 in culture supernatants remained undetectable from 24-hr to 72-hr of culture. Altogether, these data demonstrate that mast cells are highly effective inducers of immune responses in vivo which, in contrast to B cells and macrophages, provide signals for antigen-specific as well as non-specific lymphoproliferative response and IFN-γ production.

Figure 3.

Mast cells transferred in vivo into mice provide T cell with antigen-specific and non-specific proliferative response and IFN-γ production. Spleen cells from mice immunized as described in Fig. 2, were harvested 7 days after the last boost of antigen, and cultured at 4 × 106/ml alone (open bars) or in the presence of various dilutions of OVA. For simplification, only data obtained with the optimal concentration of 10 µg/ml OVA are represented (shaded bars). After 48 hr of culture, supernatants were tested for their IFN-γ content by ELISA. In parallel, cell proliferation was assessed by adding 0·25 µCi [3H]TdR/well and after an additional 16 hr of culture, cells were harvested for thymidine uptake. Data obtained are from a pool of individually cultured spleen cells from five mice per group. Values are presented as means ± SEM from three separate experiments.

Specific antibody response in Wf/Wf mast cell-deficient mice, their normal +/+ littermates, and mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice

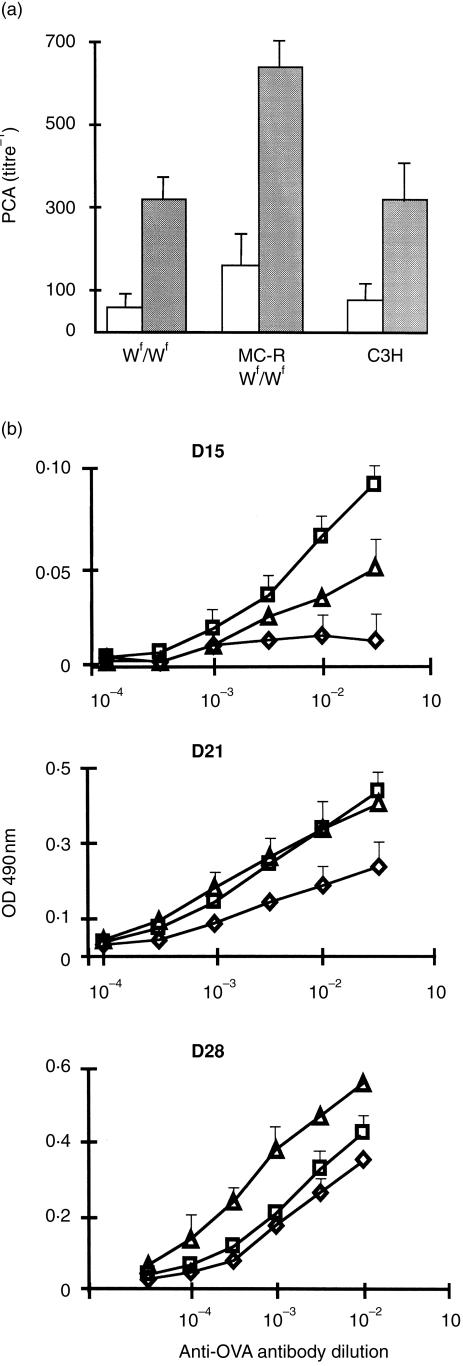

Based on the strong potential for mast cells to induce antigen-specific and non-specific IFN-γ production, mast cell-deficient Wf/Wf mice were compared to their +/+ littermates and mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice to mount specific antibody responses. The Wf mutation carried by the mouse strain used in this work has appeared spontaneously in a C3H/HeJ colony kept at the Institut Pasteur and was detected as previously described.22 Unlike other alleles of the W series, in paticular the Wv allele, the Wf allele did not result in sterility. Furthermore, the Wf allele resulted in slight anaemia but less pronounced than that found in the Wv allele. However, relationships between the Wf mutation in this particular mouse strain and the mast cell deficiency have not been established so far. Therefore we looked at the mast cell distribution in two distinct compartments, the skin and the intestinal mucosa. Figure 4 shows that although some residual mast cells can be found in both compartments, mast cells were detected at a much lower frequency in Wf/Wf mice than in their normal littermates (P = 0·0001). The different groups of mice were sensitized by injections of OVA in the presence of alum and IgE titres were evaluated by performing PCA reactions in rats passively sensitized with various dilutions of sera. As shown in Fig. 5(a), there was no difference in PCA titres between Wf/Wf mice and normal mice. However, it was striking to observe that mast cell-reconstituted mice consistently mounted significantly higher IgE reponses than other groups of mice, namely normal and Wf/Wf mice which did not show significant differences. Similarly, mast cell-reconstituted mice mounted vigorous OVA-specific IgG1 responses as compared to mast cell-deficient mice which developed a weaker response than normal mice (Fig. 5b). Kinetic studies also demonstrated that OVA-specific IgG1 antibody response took place much faster in normal and mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice than in Wf/Wf (Fig. 5b). The data were not conclusive for the OVA-specific IgG2a response due to limited amounts of antibody produced.

Figure 4.

Mast cell distribution in Wf/Wf and their +/+ littermates skin and gut mucosa. Histological samples from the same portions of duodenum and back skin were treated as described in the Materials and methods. The number of mast cells in tissue sections was evaluated with a light microscope and expressed as the mean of values from 10 different +/+ and Wf/Wf mice.

Figure 5.

Effect of mast cell deficiency on specific antibody response. Mast cell-deficient Wf/Wf mice, their +/+ littermates (C3H), and mast cell-reconstituted mice (MC-RWf/Wf), were immunized with OVA adsorbed on alum. (a) OVA-specific IgE antibodies were measured in rats by PCA reaction at day 15 (open bars, primary response) and day 21 (shaded bars, secondary response). (b) Sera from Wf/Wf (◊), normal C3H mice (▵) and mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice (□) were tested by ELISA for their OVA-specific IgG1 antibody content at days 15, 21 and 28. Each group consisted of five mice and data are from two distinct experiments.

Delayed-type hypersensitivity in mast cell-deficient Wf/Wf mice

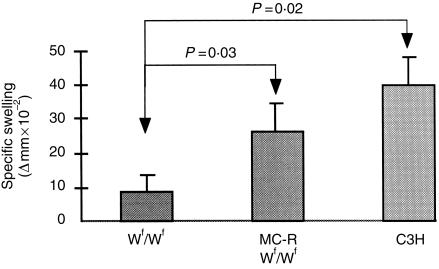

Several conflicting reports have attempted to evaluate the role of mast cells in the expression of DTH. In the light of our recent work establishing that mast cells specifically9,12 and non-specifically activate T cells23 and that DTH reactions are dependent upon T cells, it was of interest to re-evaluate responses of mast cell-deficient Wf/Wf mice to a sensitizing antigen. Homozygous Wf/Wf mutant mice were sensitized with OVA at the tail base and after 7 days they were challenged with aggregated OVA at the hind footpad. As controls, normal as well as mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice were subjected to similar treatment. As shown in Fig. 6, although all mice developed DTH responses, swelling measurements in Wf/Wf mice were significantly lower than in +/+ mice (P = 0·02). Interestingly, DTH reactions in mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice were significantly higher than in mast cell-deficient mice (P = 0·03) and did not appear different from that of normal mice (P = 0·06). These data demonstrate that mast cells do play an important role in sustaining cell-mediated immune responses.

Figure 6.

Role of mast cells in DTH reactions. Five mice in each group, Wf/Wf, mast cell-sufficient (C3H), and mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice (MC-RWf/Wf) were given subcutaneous injections of 50 µg OVA emulsified in CFA in both sides of the base of the tail. DTH reactions were induced 7 days later by injecting subcutaneously 30 µl of 1 mg/ml of aggregated OVA in the left hind footpad. The right footpad was injected with saline. Footpad thickness was assessed by subtracting values for the saline-injected footpads from those of the challenged footpads.

Discussion

The role of mast cells in host defence mechanisms against some parasite infestations, tumour induction, or bacterial infections has been extensively investigated. Most of these reports emphasized the critical role of mast cells as effector cells in innate immunity. In contrast, no study has yet attempted to demonstrate whether mast cells can participate in the expression of acquired immune responses. Two methodological approaches have been considered, the first consisted in priming naive mice with exogenously transferred in vitro antigen-pulsed mast cells. In another set of experiments, analysis of humoral and cellular specific immune responses was carried out by using mast cell-deficient mice in comparison with congenic sufficient mice and mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice.

The immune response against a soluble antigen requires its capture, processing and presentation by a variety of ‘professional’ APCs including dendritic cells, macrophages and B cells. Over the past few years, we and others have demonstrated that mast cells can process antigens and present immunogenic peptides to specific T cells via MHC class I24 or MHC class II6,12,25,26 in vitro. The present work extends our earlier studies that mast cells play a critical role in initiating antigen-specific antibody responses in vivo. Indeed a single injection of mast cells, pulsed in vitro with OVA-DNP followed by two injections of soluble antigen, gave rise to substantial amounts of anti-DNP IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies. Specific priming of the immune system by mast cells was demonstrated by the failure of unpulsed mast cells or antigen alone to elicit a detectable antibody response (Fig. 1). These data provide evidence that mast cells, in addition to their APC function, have an intrinsic adjuvant activity. To test whether mast cells induce a particular type of immune response, mast cells, B cells and macrophages were pulsed extracorporally with OVA–DNP and injected into syngeneic mice. The primary antibody response indicates the potential of mast cells and macrophages to induce IgG1 or IgG2a antibodies. Analysis of the secondary anti-DNP antibody response shows that both isotypes were induced by mast cells and macrophages whereas B cells and alum elicited a more polarized IgG1 response. Unfortunately, no anti-DNP IgE response was detected, probably because of the relatively high amount (100 µg/mouse) of OVA–DNP used for immunization and/or because of the short half-life (12 hr) of IgE antibodies. As to the cytokine profiles generated by different APCs, we consistently observed that spleen cells from mast cell-injected mice and challenged in vitro with antigen had the highest potential for inducing IFN-γ production, about six-fold more and two-fold more than those from B cell- and macrophage-injected mice, respectively. Strikingly, the basal IFN-γ concentration and cell proliferation were also elevated in spleen cell cultures from mice injected with unpulsed mast cells and not challenged with antigen in vitro. This particular antigen non-specific elevated IFN-γ concentration induced by mast cells, but not by B cells or macrophages, supports our recent findings where normal spleen cells co-cultured in vitro with mast cells or harvested from mice injected with mast cells produced large amounts of IFN-γ and IL-12.23 To draw clear conclusions on the actual potential of mast cells, B cells and macrophages to induce T helper type 1 (Th1) or Th2 polarized immune responses, one needs not only to monitor IFN-γ but also IL-4 or IL-5. Unfortunately, in our experimental system detection of IL-4 or IL-5 remained elusive. This again, as for IgE, may be due to the fairly high doses of antigen used for immunization. On the other hand, we have established this immunization regimen because it provided the optimal conditions for inducing measurable IgG1 and IgG2a antibody responses. In the absence of detectable IL-4 or IL-5 as a marker for Th2 responses, it remains unclear whether mast cells support Th1- or Th2-mediated immune responses. Based on the isotypic profile of the humoral immune response and the IFN-γ production by different APCs, mast cells and macrophages presented similar patterns of induction. In contrast to mast cells and macrophages, B cells selectively induced IgG1 but not IgG2a antibody response and only limited amounts of IFN-γ. These opposed effects of mast cells and macrophages versus B cells are consistent with several studies supporting the widespread acceptance that targeting antigen to B cells in vivo induces Th2 responses15 while dendritic cells and macrophages activate Th1 lymphocytes.15,27–29

Although numerous reports have considered in vivo transfer of cultured APCs to investigate their potential to initiate in vivo immune responses, the relevance of such function to resident tissue APCs may be questionable. It can be postulated that cultured BMMCs which have a mucosal mast cell phenotype could reflect immune functions of mucosal tissue mast cells rather than connective tissue mast cells. It is also questionable whether injected mast cells act directly as APCs to activate specific T cells or whether processed antigen or immunogenic peptides are transferred from mast cells to endogenous APCs, such as macrophages or dendritic cells. However, if this peptide exchange may happen with injected mast cells, there is no reason that this hypothesis should not apply for injected B cells and macrophages. Our current working hypothesis is that mast cells may participate concomitantly on both antigen-specific and non-specific T-cell responses. From in vitro as well as in vivo studies,23 mast cells were found to display the unique property which consists in the induction of non-specific activation of B and T lymphocytes and IL-2 and IFN-γ production. Recently, we demonstrated that mast cells secrete small vesicles called exosomes which harbour various immunologically relevant molecules such as MHC II, lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1, CD40, CD86 molecules. These exosomes, when purified, were able to activate B and T lymphocytes just as whole mast cells do (Skokos D. et al., manuscript in preparation).

To address the question whether resident mast cells contribute to the regulation of specific antibody response in vivo, genetically mast cell-deficient Wf/Wf mice were immunized with OVA in the presence of alum used as adjuvant. The anti-OVA-specific antibody response including IgE and IgG1 in Wf/Wf mice was significantly lower than in mast cell-sufficient and in mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice. This indicates that failure to mount efficient antibody responses is very likely related to the mast cell deficit.

We have recently observed that BMMC and mast cell lines such as P815 or MC-9 have the property to induce vigorous proliferative responses and IFN-γ production in a non-specific manner.23 It was therefore of interest to investigate whether another characteristic feature of T-cell reactivity, the development of DTH, had also been influenced by mast cells. We found that Wf/Wf mice developed DTH responses but significantly lower than their normal littermates. Recovery of optimal DTH responses in mast cell-reconstituted Wf/Wf mice demonstrates that the presence of mast cells is critical for the occurrence of this particular specific cellular immune response. Using the same mouse strain used in this work, Marchal et al.30 have shown that the altered DTH reaction in Wf/Wf mice was essentially caused by an impaired capacity of Wf/Wf DTH-mediating cells to circulate in the blood. Consistent with our findings, some studies have demonstrated that DTH reactions were defective in Wv/Wv and in Sl/Sld mast cell-deficient mice.31 By contrast, others have shown that DTH reactions in mast cell-deficient mice were indistinguishable from the responses of normal littermates.32,33 These apparently conflicting results, which may result from different experimental procedures, should not obscure the emerging concept of the immunoregulatory potential of mast cells. We have recently hypothesized that as a consequence of the IgE-mediated allergic response, mast cells may have the property to recruit and activate B and T cells in inflamed tissues which accounts for the occurrence of the late-phase reaction.23

From both approaches, using either transfer of in vitro pulsed mast cells into naive mice or immunization of mast cell-deficient mice, it cannot be formally implied that mast cells directly participate as APCs but it can be inferred that mast cells may act as APCs or may contribute through a ‘bystander’ mechanism (through other APCs) to support efficient specific immune responses. To investigate further the mast cell APC function in vivo, direct evidence can be provided by targeting resident mast cells via mast cell-specific receptors such as c-kit (CD117) or FcεRI. Work is in progress to investigate this issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr G. Marchal for providing advice and assistance to perform DTH experiments.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- BMMC

bone marrow-derived mast cells

- CFA

complete Freund adjuvant

- DTH

delayed-type hypersensitivity

References

- 1.Mécheri S, David B. Unravelling the mast cell dilemma: culprit or victim of its generosity? Immunol Today. 1997;18:212–15. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01034-7. 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galli S, Maurer M, Lantz C. Mast cells as sentinels of innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:53–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80010-7. 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Echtenacher B, Mannel DN, Hultner L. Critical protective role of mast cells in a model of acute septic peritonitis. Nature. 1996;381:75–7. doi: 10.1038/381075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malaviya R, Ikeda T, Ross E, Abraham SN. Mast cell modulation of neutrophil influx and bacterial clearance at sites of infection through TNF-alpha. Nature. 1996;381:77–80. doi: 10.1038/381077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malaviya R, Abraham SN. Interaction of bacteria with mast cells. Meth Enzymol. 1995;253:27–43. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)53005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frandji P, Oskéritzian C, Cacaraci F, Lapeyre J, Peronet R, David B, Guillet JG, Mécheri S. Antigen-dependent stimulation by bone-marrow-derived mast cells of MHC class II-restricted T cell hybridoma. J Immunol. 1993;151:6318–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frandji P, Mourad W, Tkaczyk C, David B, Colle JH, Mécheri S. IL-4 mRNA transcription is induced in mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells through an MHC class II-dependent signalling pathway. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:844–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199803)28:03<844::AID-IMMU844>3.0.CO;2-4. 10.1002/(sici)1521-4141(199803)28:03<844::aid-immu844>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox CC, Jewell SD, Whitacre CC. Rat peritoneal mast cells present antigen to a PPD-specific T cell line. Cell Immunol. 1994;158:253–64. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1272. 10.1006/cimm.1994.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimitriadou V, Mécheri S, Koutsilieris M, Fraser W, Al-Dakkak R, Mourad W. Expression of functional major histocompatibility complex class II molecules on HMC-1 human mast cells. J Leuk Biol. 1998;64:791–9. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.6.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poncet P, Arock M, David B. MHC class II-dependent activation of CD4+ T cell hybridomas by human mast cells through superantigen presentation. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:105–12. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inamura N, Mekori YA, Bhattacharyya SP, Bianchine PJ, Metcalfe DD. Induction and enhancement of FceRI-dependent mast cell degranulation following coculture with activated T cells: dependency on ICAM-1-and leukocyte function-associated antigen (LFA) -1-mediated heterotypic aggregation. J Immunol. 1998;160:4026–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frandji P, Tkaczyk C, Oskeritzian C, David B, Desaymard C, Mécheri S. Exogenous and endogenous antigens are differentially presented by mast cells to CD4+ T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2517–28. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denis O, Latinne D, Nisol F, Bazin H. Resting B cells can act as antigen presenting cells in vivo and induce antibody responses. Int Immunol. 1992;5:71–8. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janeway C, Jr, Ron J, Katz M. The B cell is the initiating antigen-presenting cell in peripheral lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1986;138:1051–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macauley A, DeKruyff R, Goodnow C, Umetsu D. Antigen-specific B cells preferentially induce CD4+ T cells to produce IL-4. J Immunol. 1997;158:4171–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Razin E, Cordon-Cardo C, Good RA. Growth of a pure population of mouse mast cells in vitro with conditioned medium derived from concanavalin A-stimulated splenocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2559–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frandji P, Tkaczyk C, Oskéritzian C, Lapeyre J, Peronet R, David B, Guillet JG, Mécheri S. Cytokine-dependent regulation of MHC class II expression and antigen presentation of mast cells. Cell Immunol. 1995;163:37–46. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1096. 10.1006/cimm.1995.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogawa M, Matsuzaki Y, Nishikawa S, et al. Expression and function of c-kit in hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 1991;174:63–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antoine JC, Jouanne C, Lang T, Prina E, de Chastellier C, Frehel C. Localization of MHC class II molecules in phagolysosomes of murine macrophages infected with Leishmania amazonenesis. Infec Immun. 1991;59:764–75. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.764-775.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prina E, Lang T, Glaichenhaus N, Antoine J-C. Presentation of the protective parasite antigen LACK by leishmania-infected macrophages. J Immunol. 1996;156:4318–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ovary Z, Stevens S, Caiazza R, Kojima S. PCA reactions with mouse antibodies in mice and rats. Int Archs Allergy Appl Immunol. 1975;48:16–21. doi: 10.1159/000231289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guénet J, Marchal G, Milon G, Tambourin P, Wendling F. Fertile dominant spotting (Wf): a new allele at the W locus of the house mouse. J Heredity. 1979;70:9–12. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tkaczyk C, Villa I, Peronet R, David B, Chouaïb S, Mécheri S. In vitro and in vivo immunostimulatory potential of bone marrow-derived mast cells on B and T lymphocyte activation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:134–42. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malaviya R, Twesten NJ, Ross EA, Abraham SN, Pfeifer JD. Mast cells process bacterial Ags through a phagocytic route for class I MHC presentation to T cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:1490–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tkaczyk C, Viguier M, Boutin Y, Frandji P, David B, Hebert J, Mécheri S. Specific antigen targeting to surface IgE and IgG on mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells enhances efficiency of antigen presentation. Immunology. 1998;94:318–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00525.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tkaczyk C, Villa I, Peronet R, David B, Mécheri S. FceRI-mediated antigen endocytosis turns IFN-g-treated mouse mast cells from inefficient into potent antigen presenting cells. Immunology. 1999;97:333–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00789.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cua DJ, Stohlman SA. In vivo effects of T helper cell type 2 cytokines on macrophage antigen-presenting cell induction of T helper subsets. J Immunol. 1997;159:5834–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gajewski TF, Pinnas M, Wong T, Fitch FW. Murine Th1 and Th2 clones proliferate optimally in response to distinct antigen-presenting cell populations. J Immunol. 1991;146:1750–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sornasse T, Flamand V, De Becker G, et al. Antigen-pulsed dendritic cells can efficiently induce an antibody response in vivo. J Exp Med. 1992;175:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchal G, Milon G, Guénet J. Altered circulation of lymphocytes mediating delayed-type hypersensitivity when primed in Wf/Wf mice. Immunology. 1980;39:269–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Askenase PW, Van Looveren H, Kraeuter-Kops S, et al. Defective elicitation of delayed-type hypersensitivity in W/Wv and Sl/Sld mast cell deficient mice. J Immunol. 1983;134:2687–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas WR, Schrader JW. Delayed hypersensitivity in mast cell-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1983;130:2665–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galli SJ, Hammel I. Unequivocal delayed hypersensitivity in mast cell-deficient and beige mice. Science. 1984;226:710–13. doi: 10.1126/science.6494907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]