Introduction

Guarding a large space against intruders is tricky when there are only a few of you. Lymphocytes know this only too well as the frequency of naive T or B cells specific for a given pathogen is in the order of 10−5–10−6. How then, can these rare cells survey the entire body for early signs of their foe, which can show up unpredictably at any one of many ports of entry? Direct scanning of every body surface would not be an efficient strategy. The body is a large space and, on average, detection would simply take too long, especially considering the speed with which many infectious agents replicate. Accordingly, lymphocytes in the naive pool do not, by and large, travel to peripheral tissues in search of antigen. Rather, T and B cells are confined to a pool that re-circulates via the lymph and blood between lymph nodes, spleen, Peyer's patches and similar organs. It is in these secondary lymphoid tissues (SLTs) that encounters between lymphocytes and antigens take place and, if appropriate, immune reactivity develops.

Antigen transport by dendritic cells (DC) to secondary lymphoid organs

Antigens must get to SLTs from sites of pathogen entry. There are two ways in which this can happen. Antigens can drain to SLTs by passive means or may be actively transported there by specialized cells such as dendritic cells (DC). DC are present in SLTs and in most other tissues as a trace population and are thought to be involved in the initiation of all T-cell responses.1 Studies of Langerhans cells (LC), a population of DC found in skin and mucosa, suggest that much of DC biology has been designed for bringing antigens to T cells. Freshly isolated LC are able to internalize exogenous antigens and process them for major histocompatibility class (MHC) class II presentation to T cells, but antigen acquisition and processing abilities are rapidly lost when LC are cultured in vitro.2,3 At the same time, the cells increase their expression of MHC, adhesion and costimulatory molecules and become more potent at stimulating T-cell proliferation.3–5 This process, known as ‘DC maturation’, has also been observed with DC isolated from heart, kidney, lung and other peripheral organs, and with DC grown from various progenitors.1,6 Such studies have led to the following model: DC in peripheral tissues are in an ‘immature’ state, in which they sample antigens and process them for MHC presentation (Fig. 1). This is followed by a migratory stage through lymph (where the cells are known as veiled cells) or blood, during which maturation occurs. Thus, mature DC arrive in draining SLTs (lymph nodes for veiled cells, spleen for blood-borne DC) primarily presenting on their surface those antigens that they sampled before departure and not new ones acquired upon arrival (Fig. 1).1,6 This model resolves the antigen surveillance problem for T cells: DC act as tissue sentinels, bringing antigens in processed form to the areas where T cells congregate and effectively allowing the latter to encounter antigens from the entire body. DC migration may take place continuously at a basal level but is markedly increased in response to inflammation, such as occurs after infection.6

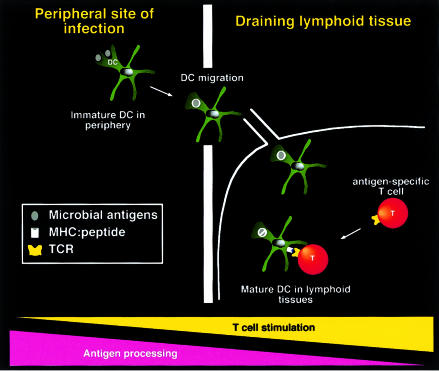

Figure 1.

Model for DC migration and maturation. Immature DC sample antigens in peripheral tissues and migrate into draining SLT where, as mature DC, they present antigens to re-circulating T cells and initiate immune responses. Although traditionally depicted in this manner, it is not actually known whether DC migration is always coupled to DC maturation. Microbial antigens are depicted as grey ovals, which are taken up and degraded in DC phagosomes (white circles).

Like T cells, B cells are also confined to SLTs. Intriguing new evidence suggests that migrating DC may also play a role in bringing non-processed antigen into SLTs for ‘presentation’ to B cells.7,8 The ability of DC to transport intact antigens may even have been exploited by certain infectious organisms such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which appear to use LC as vehicles for gaining access to T cells in lymph nodes.9,10

Antigen sampling by DC in secondary lymphoid organs

In addition to active transport, there are passive mechanisms by which antigens can reach SLTs. For example, lymph nodes collect afferent lymph draining from most body surfaces (although not all lymph-borne antigens may be accessible to lymphocytes11). Similarly, the spleen filters antigens present in the blood and Peyer's patches collect gut antigens transported across the gut wall by M cells (specialized epithelial cells). Other less well-defined accumulations of lymphoid tissue are found at most sites of pathogen entry, such as the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue that receives airborne antigens.

With so much material draining into SLTs, it is reasonable to presume that antigen-presenting cells (APC) also capture antigens locally for presentation to T cells. This would require the presence of immature, antigen-sampling DC in SLTs. Indeed, it is clear that all SLTs, like other tissues, contain resident DC that share many of the properties of freshly isolated LC. For example, freshly isolated mouse spleen DC populations contain cells that can process soluble native antigens in vitro and internalize particles by phagocytosis.12,13 As with LC, the ability of spleen DC to internalize and process antigen is lost during culture,12,13 concomitantly with upregulation of molecules involved in T-cell stimulation.14 In vivo studies also support the notion that there are immature DC in spleen and lymph nodes (LN) that can capture antigens, including particulates, although in some cases it is difficult to exclude the possibility that some of the cells captured the antigen before immigrating into SLTs.15–19

What has been less clear is what fraction of DC in SLTs is in an immature, antigen sampling as opposed to a mature, T-cell stimulatory state. This is further complicated by the fact that there exist in fact at least three distinct subsets of DC in SLTs that can be identified by differential expression of CD8 and CD4.20 The function of these individual DC types is still obscure and they have variably been proposed to be involved in regulation of tolerance and/or different types of immune responses.21–28 We recently evaluated the ability of murine DC subsets in spleen and lymph nodes to process and present the model antigen hen egg lysozyme (HEL). Following in vitro or in vivo exposure to HEL protein, over 90% of all lymph node and spleen DC subsets displayed HEL:MHC class II complexes at the cell surface, demonstrating that most SLT DC are capable of efficiently internalizing, processing and presenting native antigen29,30 (Fig. 2). Similarly, Kamath et al. have recently shown that a very high proportion of all three spleen DC subsets are phagocytic in vivo, a hallmark of immaturity.19 Thus, the vast majority of DC in SLTs, independently of subset, are in a relatively immature, antigen-processing state, whereas truly mature DC are rare, perhaps owing to their limited lifespan. The notion that immature cells represent the great majority of DC in SLTs is, perhaps, surprising but is compatible with evidence that many lymph node DC do not originate from LC but from blood-borne progenitors, which, like lymphocytes, presumably enter the node via high endothelial venules.31,32 Having a distinct cohort of resident DC able to sample antigen locally, as well as antigen-carrying migrant DC, greatly increases the number of APC presenting relevant antigens in SLTs and the chances that they will be encountered by a rare T cell (Fig. 3).

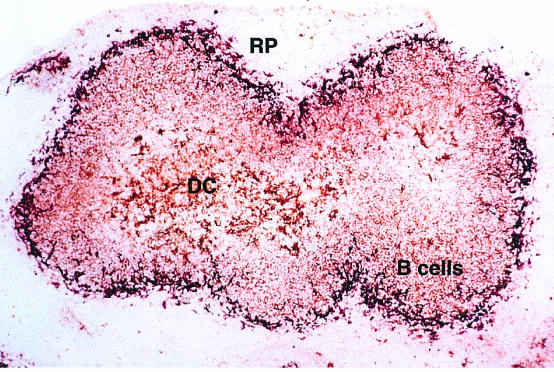

Figure 2.

DC in spleen, process and present HEL protein. This image shows the distribution of APC-bearing complexes of HEL + MHC class II in the spleen of a mouse injected i.v. 4 hr previously with HEL protein containing endotoxin. The complexes (brown) are revealed with the C4H3 monoclonal antibody (mAb), specific for HEL 46–61:I-Ak. B denotes B-cell areas, DC denotes DC areas. Metallophilic macrophages (purple staining; MOMA-1 antibody) outline the boundary between the white and red pulp (RP). The great majority of spleen DC stain with C4H3 in this experiment, arguing that they are not all recent immigrants but resident cells that acquired the antigen locally. See reference 37 for details.

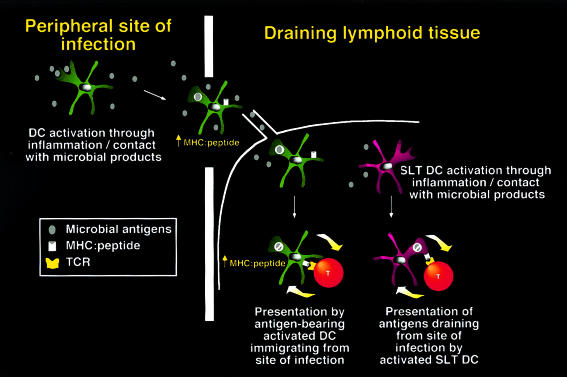

Figure 3.

Revised model for presentation by DC in SLTs. Like DC in peripheral tissues, the majority of DC in SLTs are immature and have the capacity to internalize, process and present native antigens on MHC class II. However, DC presentation is not constitutive but upregulated upon receipt of activation signals, likely to represent infection. These signals also induce activation and emigration of DC from the site of infection. As a result, two distinct populations of DC in SLTs can present antigens from pathogens following infection, one representing recent immigrants, the other representing resident SLT DC. These two pathways increase the number of APC presenting relevant antigens and maximize the chance that rare T cells specific for those antigens will be activated. The process of T-cell activation results in delivery of feedback signals to DC that further augment antigen presentation (thick arrows). The relative contribution of the two pathways for antigen presentation may depend on the abundance of antigen and the extent of inflammation.

Antigen presentation requires DC activation

Thus, lymph node DC have the potential to sample lymph contents and present them to T cells. But, a growing body of evidence suggests that they do not do so constitutively in vivo. In fact, antigen internalization by DC does not necessarily guarantee its conversion into MHC class II:peptide complexes and presentation to CD4+ T cells.30,33–36 Our own studies show that subcutaneous immunization with HEL alone does not lead to presentation of a high frequency of MHC:HEL peptide complexes by lymph node DC unless adjuvants such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or anti-CD40 are coadministered with the antigen.30 DC interactions with antigen-specific T cells in vivo also improve antigen presentation, presumably because of feedback signals30 (Fig. 3). Likewise, Inaba et al.36 have shown that HEL is internalized by LC and immature bone marrow-derived DC, reaches processing compartments, but is not converted into antigenic complexes until maturation-promoting stimuli are added to the cultures. In addition, LPS also improves HEL presentation by spleen DC after intravenous HEL immunization, although this was originally attributed to its ability to promote DC migration.37 Adjuvants may increase MHC presentation by several means, for example by promoting upregulation of MHC class II synthesis, alteration of MHC class II recycling, invariant chain cleavage, peptide loading, and/or increased transport of loaded MHC molecules to the cell surface.33–35

These results suggest a slight departure from the original model of DC as tissue sentinels actively sampling their antigenic environment. Rather, tissue-resident DC, including those in SLTs, are quiescent until they receive an activation signal (Fig. 3). In this quiescent state, DC may internalize antigens but do not necessarily generate antigenic complexes. DC activation results in loading of a cohort of MHC molecules with peptides and their display at the cell surface. However, this is a transient phenomenon as the activation signal also initiates DC maturation and leads to eventual downregulation of antigen acquisition and processing functions.

Why is it important to regulate MHC class II presentation in response to activation? Activation of DC is generally seen after infection, in response to direct recognition of microbial organisms or of hallmarks of their presence, such as inflammatory cytokines, chemokines or tissue damage.38 Co-ordinating peptide sampling and activation causes DC to present peptides associated with the activating stimulus, which suggests that DC are naturally biased to present peptides of pathogen origin. Thus, DC are not blind sentinels of the immune system, providing T cells with environmental antigens indiscriminately. Rather, DC select antigens likely to be useful for a protective immune response while allowing the T cell to make the ultimate distinction.

Interestingly, the ability to prevent loading of MHC molecules until there is a DC-activating pathogen around does not simply result in presentation of an increased total number of MHC molecules loaded with pathogen antigens. Rather, it also leads to display of an increased frequency of MHC molecules loaded with pathogen peptides compared with MHC molecules loaded with self-peptides (Fig. 4). Indeed, the most striking effect of adjuvants on HEL presentation by DC in vivo is to increase the proportion of MHC class II molecules loaded with HEL peptides.30 Thus, regulation of MHC class II presentation in DC may be designed not only to present high levels of microbial antigens but also to prevent presentation of high levels of self-peptides. Why should this be the case? The answer is not clear. It is possible that self-peptides presented by DC could act as T-cell receptor (TCR) antagonists39 or could be recognized by regulatory T cells,40 in either case decreasing the sensitivity of anti-pathogen responses. It remains to be determined whether DC similarly regulate MHC class I loading to avoid self-peptide presentation.

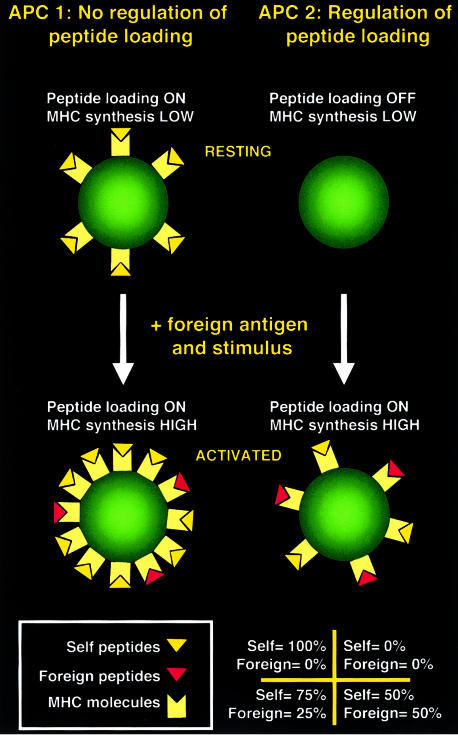

Figure 4.

Regulation of peptide loading increases the proportion of MHC class II molecules loaded with antigenic peptides. Two hypothetical APC types are shown both of which increase MHC class II synthesis by the same amount upon activation (6 molecules in this example). However, APC 1 constitutively loads MHC class II molecules with peptides while APC 2 can only do so after activation (e.g. by regulating invariant chain cleavage35). If activation is coupled with uptake of a foreign antigen (e.g. phagocytosis of a microorganism), the number of newly synthesised MHC molecules loaded with foreign versus self-peptides depends on the ratio of foreign:self-proteins that reach endosomes. Choosing a ratio of 1:1 in this example, this results in both APC presenting three new MHC molecules with foreign antigen and three new MHC molecules with self-peptides. However, although both APC present exactly the same number of antigenic complexes, these are displayed at a higher frequency on APC 2 than on APC 1 because APC 2 presents fewer self-peptides. Note that regulation of peptide loading is not the only mechanism by which DC can display a high frequency of foreign peptide-loaded MHC class II molecules. A major contributing factor is the large increase in MHC synthesis that follows activation.33,34

DC may act to tolerize T cells in the absence of infection.41 Because DC activation generally increases immunogenicity, the presence of tolerogenic DC may be seen as invalidating the model that MHC presentation is always coupled to DC activation. However, alternative forms of DC activation, unrelated to infection, may exist that do not result in increased immunogenicity.42 For example, it is possible that certain stimuli (e.g. recognition of apoptotic cells) could activate DC to present antigen without inducing the upregulation of costimulation. Certain specialized tolerogenic DC subsets may also exist that do not require activation for antigen loading onto MHC.41

Conclusion

Lymphocytes do not have an easy job surveying the entire body for the presence of infection. Their job is facilitated by the physiology of SLTs, organized lymphocyte ‘truckstops’ strategically located around the body, which collect antigens from peripheral sites. Antigens can be displayed to T cells in SLTs by immigrant DC who sample peripheral tissues, or by resident DC who sample lymph or blood contents. Importantly, antigen presentation is not constitutive but is coupled to innate signals that elicit DC activation. For example, normal lymph contents draining non-inflammatory sites are not presented at high levels by DC in draining lymph nodes, but presentation can increase rapidly upon infection. The presence of a large cohort of immature DC in SLTs and the ability of DC to select which antigens they present on MHC is likely to have evolved to maximize the expansion of rare T-cell clones specific for infectious organisms.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nancy Hogg, Jon Austyn and members of the Immunobiology Laboratory, ICRF, for helpful comments on the manuscript, and to Libby Gretz, Steve Shaw and Art Anderson for discussions.

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romani N, Koide S, Crowley M, Witmer PM, Livingstone AM, Fathman CG, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Presentation of exogenous protein antigens by dendritic cells to T cell clones. Intact protein is presented best by immature, epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1169–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romani N, Lenz A, Glassel H, Stossel H, Stanzl U, Majdic O, Fritsch P, Schuler G. Cultured human Langerhans cells resemble lymphoid dendritic cells in phenotype and function. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:600–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12319727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuler G, Steinman RM. Murine epidermal Langerhans cells mature into potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1985;161:526–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.3.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsen CP, Ritchie SC, Pearson TC, Linsley PS, Lowry RP. Functional expression of the costimulatory molecule, B7/BB1, on murine dendritic cell populations. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1215–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austyn JM. New insights into the mobilization and phagocytic activity of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1287–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wykes M, Pombo A, Jenkins C, MacPherson GG. Dendritic cells interact directly with naive B lymphocytes to transfer antigen and initiate class switching in a primary T-dependent response. J Immunol. 1998;161:1313–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludewig B, Maloy KJ, Lopez-Macias C, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Induction of optimal anti-viral neutralizing B cell responses by dendritic cells requires transport and release of virus particles in secondary lymphoid organs. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:185–96. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<185::AID-IMMU185>3.0.CO;2-L. 10.1002/(sici)1521-4141(200001)30:01<185::aid-immu185>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron PU, Freudenthal PS, Barker JM, Gezelter S, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells exposed to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells [published erratum appears in Science 1992; 257 (5078): 1848] Science. 1992;257:383–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1352913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gretz JL, Norbury CC, Anderson AO, Proudfoot AEI, Shaw S. Lymph-borne chemokines and other low molecular weight molecules reach high endothelial venules via specialized conduits while a functional barrier limits access to the lymphocyte microenvironments in lymph node cortex. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inaba K, Metlay JP, Crowley MT, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells pulsed with protein antigens in vitro can prime antigen-specific, MHC-restricted T cells in situ. J Exp Med. 1990;172:631–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reis e Sousa C, Stahl PD, Austyn JM. Phagocytosis of antigens by Langerhans cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1993;178:509–19. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girolomoni G, Simon JC, Bergstresser PR, Cruz P., Jr Freshly isolated spleen dendritic cells and epidermal Langerhans cells undergo similar phenotypic and functional changes during short-term culture. J Immunol. 1990;145:2820–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fossum S, Rolstad B. The roles of interdigitating cells and natural killer cells in the rapid rejection of allogeneic lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16:440–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830160422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macatonia SE, Knight SC, Edwards AJ, Griffiths S, Fryer P. Localization of antigen on lymph node dendritic cells after exposure to the contact sensitizer fluorescein isothiocyanate. Functional and morphological studies. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1654–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.6.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crowley M, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells are the principal cells in mouse spleen bearing immunogenic fragments of foreign proteins. J Exp Med. 1990;172:383–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inaba K, Turley S, Yamaide F, et al. Efficient presentation of phagocytosed cellular fragments on the major histocompatibility complex class II products of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2163–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamath AT, Pooley J, O'Keeffe MA, et al. The development, maturation, and turnover rate of mouse spleen dendritic cell populations. J Immunol. 2000;165:6762–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vremec D, Pooley J, Hochrein H, Wu L, Shortman K. CD4 and CD8 expression by dendritic cell subtypes in mouse thymus and spleen. J Immunol. 2000;164:2978–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suss G, Shortman K. A subclass of dendritic cells kills CD4 T cells via Fas/Fas-ligand-induced apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1789–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kronin V, Winkel K, Suss G, Kelso A, Heath W, Kirberg J, von Boehmer H, Shortman K. A subclass of dendritic cells regulates the response of naive CD8 T cells by limiting their IL-2 production. J Immunol. 1996;157:3819–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maldonado-López R, De Smedt T, Michel P, et al. CD8α+ and CD8α– Subclasses of Dendritic Cells Direct the Development of Distinct T Helper Cells In Vivo. J Exp Med. 1999;189:587–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fazekas de St Groth B. The evolution of self-tolerance: a new cell arises to meet the challenge of self-reactivity. Immunol Today. 1998;19:448–54. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01328-0. 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pulendran B, Smith JL, Caspary G, Brasel K, Pettit D, Maraskovsky E, Maliszewski CR. Distinct dendritic cell subsets differentially regulate the class of immune response in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1036–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith AL, Fazekas de St Groth B. Antigen-pulsed CD8α+ Dendritic Cells Generate an Immune Response after Subcutaneous Injection without Homing to the Draining Lymph Node. J Exp Med. 1999;189:593–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moser M, Murphy KM. Dendritic cell regulation of THI–TH2 development. Nature Immunol. 2000;1:199–205. doi: 10.1038/79734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shortman K. Burnet oration: dendritic cells: multiple subtypes, multiple origins, multiple functions. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:161–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00901.x. 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong G, Reis e Sousa C, Germain RN. Antigen-unspecific B cells and lymphoid dendritic cells both show extensive surface expression of processed antigen: MHC class II complexes after soluble protein exposure in vivo or in vitro. J Exp Med. 1997;186:673–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manickasingham S, Reis e Sousa C. In vivo regulation of antigen presentation by microbial and T cell-derived stimuli. J Immunol. 2000;165:5027–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salomon B, Cohen JL, Masurier C, Klatzmann D. Three populations of mouse lymph node dendritic cells with different origins and dynamics. J Immunol. 1998;160:708–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruedl C, Koebel P, Bachmann M, Hess M, Karjalainen K. Anatomical origin of dendritic cells determines their life span in peripheral lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2000;165:4910–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cella M, Engering A, Pinet V, Pieters J, Lanzavecchia A. Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:782–7. doi: 10.1038/42030. 10.1038/42030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pierre P, Turley SJ, Gatti E, et al. Developmental regulation of MHC class II transport in mouse dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:787–92. doi: 10.1038/42039. 10.1038/42039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierre P, Mellman I. Developmental regulation of invariant chain proteolysis controls MHC class II trafficking in mouse dendritic cells. Cell. 1998;93:1135–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inaba K, Turley S, Iyoda T, et al. The formation of immunogenic major histocompatibility complex class II-peptide ligands in lysosomal compartments of dendritic cells is regulated by inflammatory stimuli. J Exp Med. 2000;191:927–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reis e Sousa C, Germain RN. Analysis of adjuvant function by direct visualization of antigen presentation in vivo: endotoxin promotes accumulation of antigen- bearing dendritic cells in the T cell areas of lymphoid tissue. J Immunol. 1999;162:6552–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reis e Sousa C, Sher A, Kaye P. The role of dendritic cells in the induction and regulation of immunity to microbial infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:392–9. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(99)80066-1. 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basu D, Williams CB, Allen PM. In vivo antagonism of a T cell response by an endogenously expressed ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14332–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells: key controllers of immunologic self-tolerance. Cell. 2000;101:455–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinman RM, Turley S, Mellman I, Inaba K. The induction of tolerance by dendritic cells that have captured apoptotic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:411–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goerdt S, Orfanos CE. Other functions, other genes: alternative activation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 1999;10:137–42. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]