Abstract

Intranasal immunization of BALB/c strain mice was carried out using baculovirus-derived human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) β-chain, together with Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Gonadotrophin-reactive immunoglobulin A (IgA) was induced in a remote mucosal site, the lung, in addition to a systemic IgG response. The extensive sequence homology with luteinizing hormone (LH) results in the production of LH cross-reactive antibodies when holo-hCG is used as an immunogen. In contrast to wild-type hCGβ, a mutated hCGβ-chain containing an arginine to glutamic acid substitution at position 68 did not induce the production of antibodies which cross-react with LH. Furthermore, the epitopes utilized in the B-cell response to the mutated hCGβ shifted away from the immunodominant region of the parent wild-type molecule towards epitopes within the normally weakly immunogenic C terminus. This shift in epitope usage was also seen following intramuscular immunization of rabbits. Thus, a single amino acid change, which does not disrupt the overall structure of the molecule, refocuses the immune response away from a disadvantageous cross-reactive epitope region and towards a normally weakly immunogenic but antigen-unique area. Similar mutational strategies for epitope-refocusing may be applicable to other vaccine candidate molecules.

Introduction

Many antigens considered for use in vaccines will contain several epitopes, some of which may be advantageous for the production of neutralizing antibodies whilst others may stimulate responses which are harmful to the host or which are unable to elicit the desired protection. For example, the unwanted epitopes may cross-react with self-proteins in the host, leading to an autoimmune response as in the case of Trypanosoma cruzi and nervous tissue,1 they may undergo rapid mutation and thus fail to elicit a broadly protective immune response [e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) gp120, malaria, African trypanosomiasis], or suppress an otherwise protective immune response (e.g. Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis).2 In such situations it would be highly desirable to exclude the unwanted parts of the antigen. In the case of T-cell epitopes this may be achieved by the construction of multiple antigenic peptides containing only the beneficial T-cell epitopes in a tandem array to form a synthetic polypeptide (for a recent review see ref. 3). For B-cell epitopes it is more difficult because the epitopes are usually discontinuous and therefore require correct folding of the antigen to form the immunogenic region of the protein. Though synthetic peptides containing part of the epitope have been used, the high entropy of such peptides in solution produces antibodies with relatively low affinity for the native antigen.

An alternative strategy is to develop epitope-specific molecules by selectively mutating the targeted epitope without affecting the overall folding of the polypeptide chain.4 We have investigated this possibility using the β-chain of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCGβ, Fig. 1) as a model. The glycoprotein hormone family of which hCG is a member also includes follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). They are all heterodimers containing a common α-subunit and a hormone-specific β-subunit. The FSH, TSH and LH β-chains have extensive sequence homologies, respectively, 36%, 46% and 85% to the first 114 of the 145 amino acid residues of hCGβ. The remaining C-terminal amino acids of hCGβ are referred to as the C-terminal peptide. The extensive sequence homology with LH results in the production of LH cross-reactive antibodies when hCG is used as an immunogen.5

Figure 1.

A computer-generated space-filled model of hCG highlighting residue hCGβR68. The α-subunit is indicated in dark grey and the β-subunit is shown in pale grey with the N terminus of the β-subunit and residue βR68 indicated in black. Human CG is a member of the cysteine-knot family21 in which a triple-loop structure for each subunit is held together by three disulphide bonds in a knot-like conformation, with loops 1 and 3 comprising one end of each subunit. The α- and β-subunits are oriented opposite to each other such that loops 1 and 3 of each subunit form either end of a cigar-like structure which is stabilized by a fourth short loop structure of the β-subunit, the seatbelt.13,14 Note that the CTP (β:110–145) is absent from the structure.

To reduce the LH cross-reactivity of hCGβ we have previously engineered a number of hCGβ mutants in which selected amino acid residues whose side chains protruded from the surface were substituted with different amino acids present in other members of the glycoprotein hormone family, thus optimizing the probability of correct folding of the mutated polypeptide chain.6 We showed that a substitution of a single arginine at position 68 by glutamic acid, hCGβ(R68E), eliminated the binding of a number of conformation-dependent LH cross-reactive monoclonal antibodies (mAb) without affecting the binding of hCG-specific (non-cross-reactive) mAb. In the present study we have investigated the immunogenicity of hCGβ(R68E) and report here that this single amino acid replacement dramatically re-focuses the immune response away from the immunodominant cross-reactive epitope region towards epitopes which evoke a relatively weak response when the native antigen is used as the immunogen. In addition, since hCG is initially produced at the mucosal interface in the uterus, we have compared the systemic and mucosal (lung) antibody responses in mice following mucosal immunization.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal anti-hCG antiserum (#C-8534) and mAb PE-4, PC-2 and ZBMCG27 were purchased from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK). Two additional anti-hCG mAbs, 9B4 and 2F4/3 were obtained from Biogenesis (Poole, Dorset, UK). The rabbit affinity-purified polyclonal anti-CTP was a generous gift from Professor V. C. Stevens (Ohio State University). Secondary antibodies, conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or alkaline phosphatase (AP), were purchased from Sigma.

Antigens

The holo-hCG αβ heterodimer and the isolated hCGβ-chain were both purified from urine taken during pregnancy and obtained from Zymed (South San Francisco, CA). Recombinant wild-type hCGβ (BAChCGβ) and mutant (BAChCGβ(R68E)) were produced in insect cells as described below. The CTP sequence of hCGβ was synthesized as a peptide and provided as a kind gift by Professor V. C. Stevens, Ohio State University. LH was provided by Dr A. F. Parlow, Harbor-UCLA.

Plasmid construction

Full-length cDNA encoding wild-type hCGβ6 and hCGβ(R68E) (hCGβ mutant 76) were subcloned into pLitmus28 (New England Biolabs, Beverley, MA) using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and a T7 promoter sense primer (5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC) and the antisense primer (5′-ACGTCTAGAAAACATTGATTACTGCTGGTGCTGCTGGTGGTCGACTTGTGGGAGGATCGG) containing a SalI site and His6-tag in front of the protein translation stop codon. The cDNAs were subsequently subcloned as an XbaI fragment or an EcoRV–XbaI fragment into the XbaI site or XbaI–SmaI site, respectively, of pBAC2 (Invitrogen, Groningen, the Netherlands) transfer vector, thus bringing the expression of the wild-type and mutant hCGβ genes under the control of the baculovirus P10 promoter. The recombinant P10-regulated genes encoding the wild-type and mutant hCGβ were then homologously recombined with baculovirus after co-transfection of the recombinant transfer vectors with BaculoGold DNA (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) in the insect cell line Sf9 (Spodoptora frugiperda) following the manufacturer's instructions. Recombinant baculoviruses were isolated and plaque-purified twice before being propagated to form the high titre virus stocks in Sf9 cells used for the production of recombinant hCGβ wild-type (BAChCGβ) and hCGβ(R68E)-mutant (BAChCGβ(R68E)) proteins. The production of recombinant proteins was carried out in High Five™ cells (BTI-TN-5B1-4 from Invitrogen). Both High Five and Sf9 cells were grown at 27° in BaculoGold protein-free insect medium (Pharmingen) with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco BRL, Paisley, UK) as suspension cultures. For Sf9 cells the medium was supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL).

Protein purification

The media from virus-infected High Five cultures infected at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 10 were harvested by centrifugation 72 hr post-infection, and the supernatant was immediately frozen and kept at −80° until purified. The recombinant proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using a nickel-charged resin (ProBond, Invitrogen) packed in a HR 5/10 FPLC column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Bucks, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The bound protein was eluted using a linear gradient of 0·0 m to 0·5 m imidazole followed by extensive dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°. The purified proteins, 98% pure judged by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, were stored in aliquots at −80° until use.

Immunization

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan Olac (Bicester, UK) and were used between 6 and 8 weeks of age. Escherichia coli heat-labile toxoid (LT) was kindly provided by Mariagrazia Pizza (Chiron, Siena, Italy). BALB/c mice were lightly anaesthetized with halothane and immunized intranasally on days 0 and 21 with 30 µl of LT either alone or non-covalently mixed with 10 µg of holo-hCG, hCGβ, BAChCGβ or BAChCGβ(R68E). Two weeks after the second immunization the mice were killed by cardiac exsanguination under terminal anaesthesia. Lung lavages were performed by flushing and aspirating 1 ml of PBS containing 0·1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) six times through a small incision made in the upper trachea. Vaginal lavages were performed by flushing and aspirating 0·2 ml of PBS containing 0·1% BSA.

For immunization in rabbits, 300 µg BAChCGβ(R68E) was incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 100 molar excess of N-succinimidyl-3[4-iodoacetyl]aminobenzoate (SIAB) (Pierce, Chester, UK) and then desalted using Sephadex G25 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) chromatography. The modified protein was mixed with 400 µg tetanus toxoid (TT) (Pasteur Merieux Connaught, Marcy l'Etoile, France), which had previously been cross-linked with 100 molar excess of N-succinimidyl-3[2-pyridyldithio]proprionate (SPDP) (Pierce) for 30 min at room temperature followed by desalting using Sephadex G25. The proteins were incubated overnight at 4°. Rabbits were primed intramuscularly with 100 µg BAChCGβ(R68E)-TT conjugate mixed (1:1/v:v) with 100 µl Ribi Adjuvant System (MPL + TDM + CWS) (monophosphoryl lipid A+trehalose dicorynomycolate+cell wall skeleton) (Sigma) and boosted by the same route with an equal amount of conjugate 3 weeks later.

Immunoassays

Nunc MaxisorpC plates were coated at 4° overnight with 50 µl per well of holo-hCG, hCGβ, human pituitary LH (courtesy of Dr A. F. Parlow, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA), BAChCGβ, BAChCGβ(R68E), or CTP at 1·0 µg/ml in 0·05 m carbonate–bicarbonate buffer (CBB) pH 9·6. The plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0·05% Tween-20 (PBS-T), followed by blocking with 2% dried skimmed milk powder in CBB overnight at 4°. After washing three times with PBS-T, 50 µl serum (from the immunized or non-immunized mice) or mAbs diluted in PBS-T was added and incubated for 2 hr at 37°. The plates were washed three times with PBS-T before a goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) AP-conjugated antibody (Sigma) was added for 2 hr at 37°. Following a further three washes in PBS-T and one wash in CBB, the substrate p-nitrophenylphosphate (Sigma) in CBB containing 2 mm MgCl2 was added, the plates were left for 15 min and then absorbance was read at 405 nm (A405) using an MR5000 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader (Dynatech Laboratories Ltd, Billinghurst, Kent, UK). In each assay a 1:1000 dilution of the hCGβ-specific mAb 2F4/3 (Biogenesis) was included as an inter-ELISA control.

The total secretory IgA (sIgA) in lung and vaginal lavages was quantified using end-point ELISA as described previously.7 Antigen-specific sIgA levels in these lavages were then measured using the ELISA described above for the sera samples. Instead of sera, 50 µl of lavages at 1:5 dilutions (from the immunized and non-immunized mice), or purified IgA, were tested against the specific and cross-reactive antigens. The secondary antibody was an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA (Sigma). The levels of antigen-specific IgA were normalized to the corresponding total sIgA measurement.

Results

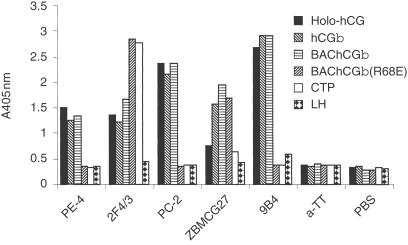

Antigenicity of the baculovirus-expressed recombinant proteins

High Five™ insect cells infected with the appropriate construct produced recombinant protein [BAChCGβ or BAChCGβ(R68E)] with an apparent MW of 25 000, which is slightly smaller than that of hCGβ purified from the urine of pregnant women (MW 43 000) due to differences in the glycosylation of the recombinant and human-derived proteins. To characterize partially the baculovirus-derived recombinant proteins affinity purified from day 3 insect cell supernatants, we used a conventional ELISA assay with a panel of mAbs. As we have shown previously using expression in COS-7 cells,6 hCGβ(R68E) fails to react with a number of LH cross-reactive mAbs but still reacts with mAbs which recognize the hCG-specific β1, β6 and β7 epitopes8 (results not shown). A comparison of the reactivity of five different hCG-specific mAbs, whose epitopes have not been mapped, with holo-hCG (i.e. the αβ heterodimer), hCGβ, BAChCGβ, BAChCGβ(R68E), CTP and LH is shown in Fig. 2. The antigenicity of the baculovirus-derived hCGβ is indistinguishable from human-derived hCGβ demonstrating that differences in the glycosylation did not affect the binding of any of the mAbs used. The hCGβ-specific mAb ZBMCG27 binds all three β-subunits to an equal extent, indicating that the R68E substitution has not significantly affected the folding and conformation of the epitope recognized by this mAb, although the epitopes recognized by the hCG-specific mAbs PE-4, PC-2 and 9B4 appear to be affected by the R68E substitution. Particularly striking, however, is that the CTP-specific mAb 2F4/3 shows more pronounced binding to BAChCGβ(R68E) than to either holo-hCG or hCGβ, irrespective of the source of the hCGβ protein. This suggests that, although distant from the C terminus in the primary amino acid sequence, the R68E substitution alters the conformation of the C-terminal sequence either directly, perhaps through charge interactions with arginine or lysine residues in the C-terminal extension, or indirectly as a result of self-aggregation of the mutant β chain.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the conformation of BAChCGβ and BAChCGβ (R68E) with different hCG-specific mAb: 1 µg/ml of pregnancy-urine-derived holo-hCG, pregnancy-urine-derived hCGβ, BAChCGβ, BAChCGβ(R68E), synthetic CTP or pituitary-derived LH were coated on to ELISA plates and tested for reactivity with the hCG-specific and irrelevant (anti-TT) mAb.

Systemic immunity

We next wished to examine whether the R68E substitution of hCGβ affected the immunogenicity of the recombinant protein. Groups of five mice were immunized intranasally with BAChCGβ or BAChCGβ(R68E), with holo-hCG and hCGβ purified from the urine of pregnant women as controls. Heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) from E. coli was used as the adjuvant for these immunizations. LT is a potent immunogen that can elicit both enterotoxin-specific serum IgG and enterotoxin-specific sIgA at different mucosal sites when administered intranasally. In addition, LT can function as an adjuvant (without the need for covalent attachment to the antigen) with respect to both systemic and mucosal immune responses.7,9–12

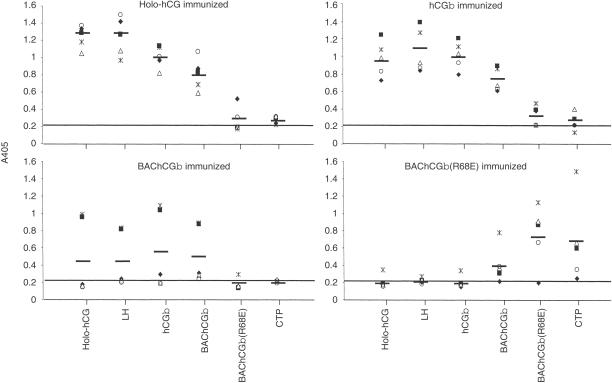

The specificity of the antisera was characterized by ELISA using different target antigens; holo-hCG, LH, hCGβ, BAChCGβ, BAChCGβ(R68E) and CTP (Fig. 3). Sera from mice immunized with hCG holo-hormone reacted strongly not only with the immunogen itself but also with the free β-subunit, irrespective of whether the latter was of human or insect cell origin (Fig. 3). In addition, as would be anticipated, the sera bound as strongly to LH as to the free hCGβ-subunits. However, only one of the holo-hCG-immunized animals produced a response with detectable reactivity to the mutant BAChCGβ(R68E), and none of the antisera contained detectable levels of CTP-binding IgG.

Figure 3.

Serum IgG responses of BALB/c mice (n = 5) immunized intranasally with LT mixed non-covalently with holo-hCG, hCGβ, BAChCGβ, or BAChCGβ(R68E). The antigen-specific IgG in a 1:100 dilution of the sera was determined in an ELISA on plates coated with hCG holohormone, LH, hCGβ, BAChCGβ, BAChCGβ(R68E) and CTP. Each symbol indicates the result for one serum sample read at A405 with the mean values indicated with a bar. Mice immunized with LT alone gave an OD of 0·2, indicated by the continuous line.

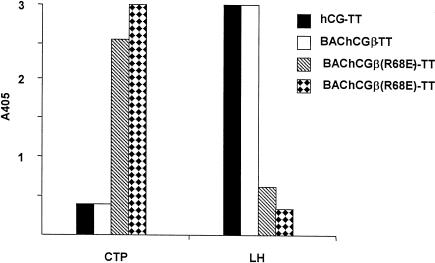

Irrespective of the origin of the hCGβ, this molecule elicited IgG that reacted equally well with holo-hCG, LH and hCGβ (Fig. 3), although only two of the animals immunized with BAChCGβ produced antisera with appreciable titres. Although these antisera contained BAChCGβ(R68E)-reactive antibodies the levels were significantly lower than those reacting with the specific immunogen (Fig. 3). The antisera from these wild-type holo-hCG/hCGβ-immunized mice contained only extremely low levels of CTP-reactive antibodies (Fig. 3). This contrasted with the result obtained following immunization with mutant BAChCGβ(R68E) (Fig. 3). Four out of the five immunized animals produced antibodies to the immunogen, but only a small fraction of the BAChCGβ(R68E)-specific antibody bound to BAChCGβ, and no holo-hCG, hCGβ, or LH cross-reactivity was observed (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, significant binding was detected with the CTP, with one of the antisera showing quite substantial reactivity. The shift in epitope usage was more dramatically demonstrated by the immunization of rabbits with holo-hCG, hCGβ, or BAChCGβ(R68E) each covalently coupled to TT. As shown in Fig. 4 the sera from the rabbits immunized with BAChCGβ(R68E)-TT had high levels of anti-CTP antibodies but contained no or very low levels of LH cross-reactive antibodies. However, rabbits immunized with either hCG-TT or BAChCGβ-TT produced high levels of LH cross-reactive antibodies but undetectable amounts of CTP-specific IgG. This clearly indicates that a single substitution of R68 with a glutamic acid residue significantly alters not only the antigenicity, as reported previously,6 but also substantially affects the immunogenicity of the recombinant protein both in mice and in rabbits.

Figure 4.

Specificity of antisera (diluted 1:500) from rabbits immunized with holo-hCG (rabbit hCG-TT), BAChCGβ (rabbit BAChCGβ-ΤΤ), or BAChCGβ(R68Ε) (two rabbits, BAChCGβ (R68E)) covalently coupled to TT. The antigen-specific IgG responses were determined in an ELISA on a plate coated with CTP or LH. Each bar represents serum from one rabbit read at A405.

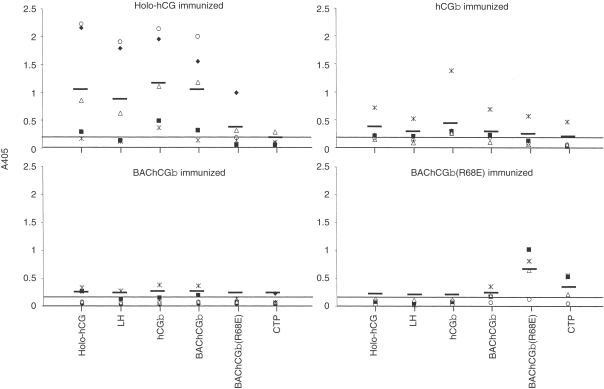

Mucosal immunogenicity

Intranasal immunization using LT as an adjuvant can elicit sIgA at distant mucosal sites. We therefore examined the antigen-specific sIgA in lavages from both the lung (Fig. 5) and the vagina (result not shown). Mice immunized with holo-hCG produced appreciable levels of antigen-specific sIgA with reactivities very similar to those observed for serum IgG responses (Fig. 3). Of the other immunogens, BAChCGβ(R68E) elicited a heterogeneous lung sIgA response with specificity for the immunogen and to a much lesser degree for CTP, albeit still significantly greater (P = 0·042, unpaired Student's t-test) than that seen in the holo-hCG immunized animals; further confirming the shift in the epitope usage for the R68E mutant. A substantially lower level of antigen-specific sIgA was detected in the vaginal washes with only two of the holo-hCG-immunized mice producing detectable levels of immunogen-specific sIgA (result not shown).

Figure 5.

Secretory IgA responses in lung lavages of BALB/c mice immunized intranasally with LT or LT mixed with holo-hCG, hCGβ, BAChCGβ, or BAChCGβ(R68E). The lavages were centrifuged to separate mucus before the total IgA was determined using ELISA. Samples were subsequently examined for specific antigen recognition using ELISA. Each symbol represents an individual mouse with the result for a 1:5 dilution of the lung lavage measured at A405 normalized to their total IgA content. The mean values are indicated by the bars. Lung lavages from mice immunized with LT alone gave a background value of 0·11 units, indicated by the continuous line.

Discussion

Epitope specificity of the immune response to hCG

Human chorionic gonadotrophin is a structurally13,14 and immunologically (see ref. 15 for a recent review) well-characterized molecule. Using panels of mAbs, two dominant epitope clusters have been located on the α-subunit, and 13 β-subunit-specific epitope clusters have been defined, four of which are located on the C-terminal peptide (amino acid residues 110–145). Two of the β-subunit specific clusters are located on the interface between the α- and β-subunits and are therefore only accessible on the free β-subunit. There is also at least one holo-hormone-specific epitope cluster, which has contact residues derived from both the α- and the β-subunit and is referred to as the C epitope cluster (not to be confused with the β-chain-specific CTP epitopes). Apart from the four CTP-specific epitopes, which are linear, all the other epitopes are discontinuous.

As most of the epitope clusters have been defined with mouse mAbs, there may be differences in the relative dominance of each epitope cluster following a polyclonal antibody response in vivo. Mice immunized intranasally with LT and holo-hCG produced antigen-specific IgG systemically with an apparently equal fraction of this IgG reacting with the purified hCGβ-subunits and with LH (Fig. 3). Since no CTP-reactivity was detectable in these animals, and because most of the hCGβ-immunoreactivity in mice immunized with hCGβ cross-reacts with LH (Fig. 3), we presume that these antibodies are essentially predominantly directed against the immunodominant but cross-reactive epitopes located in the tip of the β-subunit (see15). This would, by implication, suggest that the hCGβ-unique epitopes make only a relatively weak contribution to the immune response, irrespective of whether holo-hCG or the purified β-subunit is used for immunization, since antibodies with this specificity would not bind to LH.

Effect of the R68E substitution on the immunogenicity of hCG

Human CGβ(R68E) differs from hCGβ only in a single amino acid residue at position 68 located on loop 3 close to the tip of the β-subunit (Fig. 1). We have shown previously6 that this substitution has a major impact on the antigenicity of the molecule, because the mutant expressed in COS7 cells as a transmembrane fusion protein failed to bind all LH cross-reactive mAbs tested.8 Furthermore, these studies revealed that the arginine to glutamic acid substitution did not affect the binding of the mAbs to the hCGβ-specific discontinuous epitopes present on the holo-hormone (confirmed for one of the mAbs by unpublished BIACORE analysis) and on the interface with the α-subunit6, demonstrating that the polypeptide chain folds correctly for these structures, although the binding site for mAbs PE-4, PC-2 and 9B4 tested here did seem to be affected by the R68E substitution (Fig. 2). As we have shown here in the present experiments, the arginine to glutamic acid substitution at position 68 also has a profound effect on the immunogenicity of the recombinant protein, BAChCGβ(R68E). Mice and rabbits immunized with this protein produced BAChCGβ(R68E)-reactive IgG which does not cross-react with LH, confirming that the immunodominant cross-reactive epitope region has been functionally eliminated. It was, however, unexpected that the mouse antisera contained no reactivity towards either holo-hCG or free hCGβ subunits, with most of the immune response focused on epitope(s) present on the C-terminal region (residues 110–145) of the polypeptide. This may be because the substitution of a basic amino acid (arginine) for an acidic amino acid (glutamic acid) profoundly affects the electrostatic microenvironment of the cross-reactive epitope region, so that a significantly reduced number of B-cell receptors can interact with this part of the molecule. Alternatively the change in immunogenicity could be structurally related. We have identified one CTP-specific mAb, 2F4/3, which shows stronger binding to BAChCGβ(R68E) than to BAChCGβ, hCGβ, or holo-hCG (Fig. 2). This is unlikely to be due to differences in the oligosaccharides of insect- and human-derived glycoproteins, because all the mAbs reacted to the same extent with BAChCGβ as with hCGβ purified from human urine. The C-terminal region contains three arginines (at positions 112, 114 and 133) and one lysine (position 122). The glutamic acid at position 68 of hCGβ(R68E) could conceivably form a salt bridge with one or perhaps more of these basic amino acids, thus giving the C-terminal region a more restricted defined structure. The crystal structure of hCG showed no solvable conformation for the C-terminal peptide, suggesting that it floats as a free entropy-rich peptide chain and implying that B-cell epitopes on the C-terminal region will be immunogenically much weaker in the holo-hormone than epitopes on the remainder of the molecule. If, however, the C-terminus becomes fixed into a defined structure by an electrostatic interaction between glutamic acid at position 68 and one or more basic residues in the C terminus, it could block the accessibility to the epitope regions at the tip of the β-chain either directly, or indirectly through the four O-linked glycans in the C-terminal region. Furthermore, a structurally fixed C terminus would create a protruding loop structure, which may be responsible for the generation of a new immunodominant epitope(s) not well presented in the native molecule. It is notable that the immunodominant but hypervariable parts of the envelope proteins of several pathogens (e.g. HIV gp120 and measles virus H protein) protrude from the surface of the protein and have linear sequences as important parts of their B-cell-receptor-reactive structures.

Mucosal immune response

We and others have previously shown that mice intranasally immunized with proteins mixed with LT or cholera toxin B not only produce a systemic IgG response but also antibody responses at different mucosal sites.7,9–12,16–19 As has been shown for model immunogens such as ovalbumin, the C-fragment of TT11,12 and herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein,19 mice immunized intranasally with hCG mixed with LT will produce antigen-specific IgG in the serum as well as sIgA in both the respiratory and genital tracts. There was a strong correlation between the levels of immunogen-specific serum IgG and mucosal sIgA, and we saw no apparent differences in the spectrum of epitopes used for the mucosal antibodies in the respiratory tract compared to the epitope usage of the immunogen-specific IgG in the sera. This is consistent with the assumption that the antibody-producing cells migrate from the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue to populate other mucosal and systemic sites.20 Johansson and colleagues18 showed that specific IgG and sIgA were present in both respiratory and genital mucosal sites following nasal or vaginal immunization. In agreement with others,7,9–12,16–19 the level of specific sIgA in the lung lavages was greater than that of the vaginal lavages where only two of the animals immunized with hCG produced detectable levels of sIgA. Increasing the level of immunoglobulins at the mucosal sites would require covalent linkage of holo-hCG or its β-subunits to a carrier protein that can provide stronger T-cell help, and it is noteworthy that higher antibody titres were observed when the α-subunit of hCG was present as a potential carrier moiety.

Thus we have demonstrated here that a single amino acid substitution of arginine for a glutamic acid at position 68 of hCGβ dramatically shifts the epitope usage of the molecule by eliminating recognition of the immunodominant but LH cross-reactive epitope and focuses the response on the normally weak C-terminal epitopes. This type of approach might therefore also be applicable for the selective elimination of undesired immunodominant epitopes in other vaccine candidate molecules.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the technical assistance of Ms Inger Bjørndahl in preparing the recombinant baculovirus and for the infection of the insect cells. The financial support of The Wellcome Trust in carrying out this work is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Van Voorhis WC, Eisen H. Fl-160. A surface antigen of trypanosoma cruzi that mimics mammalian nervous tissue. J Exp Med. 1989;169:641–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delves PJ, Lund T, Roitt IM. Can epitope-focused vaccines select advantageous immune responses? Mol Med Today. 1997;3:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(96)20036-x. 10.1016/s1357-4310(96)20036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suhrbier A. Multi-epitope DNA vaccines. Immunol Cell Biol. 1997;75:402–8. doi: 10.1038/icb.1997.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roitt IM. Basic concepts and new aspects of vaccine development. Parasitol. 1989;98:S7–S12. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000072218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talwar GP, Singh O, Pal R, et al. A vaccine that prevents pregnancy in women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8532–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson AM, Klonisch T, Lapthorn AJ, et al. Identification and selective destruction of shared epitopes in human chorionic gonadotropin beta subunit. J Reprod Immunol. 1996;31:21–36. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(96)00978-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douce G, Giuliani MM, Giannelli V, Pizza MG, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Mucosal immunogenicity of genetically detoxified derivatives of heat labile toxin from Escherichia coli. Vaccine. 1998;16:1065–73. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)80100-x. 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dirnhofer S, Madersbacher S, Bidart JM, et al. The molecular basis for epitopes on the free beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), its carboxyl-terminal peptide and the hcg-beta core fragment. J Endocrinol. 1994;141:153–62. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1410153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Tommaso A, Saletti G, Pizza M, et al. Induction of antigen-specific antibodies in vaginal secretions by using a nontoxic mutant of heat-labile enterotoxin as a mucosal adjuvant. Infect Immunol. 1996;64:974–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.974-979.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douce G, Fontana M, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Intranasal immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of site-directed mutant derivatives of cholera toxin. Infect Immunol. 1997;65:2821–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2821-2828.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Magistris MT, Pizza M, Douce G, Ghiara P, Dougan G, Rappuoli R. Adjuvant effect of non-toxic mutants of E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin following intranasal, oral and intravaginal immunization. Dev Biol Stand. 1998;92:123–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giuliani MM, Del Giudice G, Giannelli V, et al. Mucosal adjuvanticity and immunogenicity of LTR72, a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin with partial knockout of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1123–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapthorn AJ, Harris DC, Littlejohn A, et al. Crystal structure of human chorionic gonadotropin. Nature. 1994;369:455–61. doi: 10.1038/369455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu H, Lustbader JW, Liu Y, Canfield RE, Hendrickson WA. Structure of human chorionic gonadotropin at 2.6 Å resolution from mad analysis of the selenomethionyl protein. Structure. 1994;2:545–58. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund T, Delves PJ. Immunological analysis of epitopes on hCG. Rev Reprod. 1998;3:71–6. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0030071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergquist C, Lagergard T, Lindblad M, Holmgren J. Local and systemic antibody responses to dextran-cholera toxin B subunit conjugates. Infect Immunol. 1995;63:2021–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2021-2025.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell MW, Moldoveanu Z, White PL, Sibert GJ, Mestecky J, Michalek SM. Salivary, nasal, genital, and systemic antibody responses in monkeys immunized intranasally with a bacterial protein antigen and the cholera toxin B subunit. Infect Immunol. 1996;64:1272–83. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1272-1283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson EL, Rask C, Fredriksson M, Eriksson K, Czerkinsky C, Holmgren J. Antibodies and antibody-secreting cells in the female genital tract after vaginal or intranasal immunization with cholera toxin B subunit or conjugates. Infect Immunol. 1998;66:514–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.514-520.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ugozzoli M, O'Hagan DT, Ott GS. Intranasal immunization of mice with herpes simplex virus type 2 recombinant gd2: The effect of adjuvants on mucosal and serum antibody responses. Immunol. 1998;93:563–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mestecky J. The common mucosal immune system and current strategies for induction of immune responses in external secretions. J Clin Immunol. 1987;7:265–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00915547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isaacs NW. Cystine knots. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:391–5. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]