Abstract

Recent studies indicate that T helper type 1 (Th1) and 2 (Th2) lymphocytes differ in their expression of molecules that control T-cell migration, including adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors. We investigated the relationship between cytokine production and expression of the homing receptor integrin α4/β7 on T cells. We began by analysing cytokine production by human CD4+ CD45RA– memory/effector T cells following brief (4 hr) stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin. α4/ CD4+ T cells were more likely to produce the Th1 cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ) than were α4/β7− CD4+ T cells in all six subjects studied. In contrast, production of the Th2 cytokine interleukin-4 (IL-4) was similar on α4/

CD4+ T cells were more likely to produce the Th1 cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ) than were α4/β7− CD4+ T cells in all six subjects studied. In contrast, production of the Th2 cytokine interleukin-4 (IL-4) was similar on α4/ and α4/β7− CD4+ T cells. In addition, we found that human CD4+ CD45RA– T cells that adhered to the α4/β7 ligand mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) had a greater capacity to produce IFN-γ than did non-adherent cells, suggesting that the association between α4/β7 expression and IFN-γ production has functional significance. These results suggested that primary activation under Th1-promoting conditions might favour expression of α4/β7. We directly examined this possibility, and found that naïve murine CD4+ T cells activated under Th1-promoting conditions expressed higher levels of α4/β7 compared to cells activated under Th2-promoting conditions. The association between α4/β7 expression and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells may help to determine the cytokine balance when MAdCAM-1 is expressed at sites of inflammation in the intestine or elsewhere.

and α4/β7− CD4+ T cells. In addition, we found that human CD4+ CD45RA– T cells that adhered to the α4/β7 ligand mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) had a greater capacity to produce IFN-γ than did non-adherent cells, suggesting that the association between α4/β7 expression and IFN-γ production has functional significance. These results suggested that primary activation under Th1-promoting conditions might favour expression of α4/β7. We directly examined this possibility, and found that naïve murine CD4+ T cells activated under Th1-promoting conditions expressed higher levels of α4/β7 compared to cells activated under Th2-promoting conditions. The association between α4/β7 expression and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells may help to determine the cytokine balance when MAdCAM-1 is expressed at sites of inflammation in the intestine or elsewhere.

Introduction

The selective migration of T lymphocytes to target organs depends upon adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors expressed on these cells.1,2 Adhesion molecules, including members of the integrin and selectin families, promote lymphocyte attachment by binding to ligands (‘addressins’) expressed on the surface of endothelial cells. Chemokine receptors help control lymphocyte migration both by triggering integrin-mediated adhesion and by stimulating chemotaxis. The combination of addressins and chemokines presented on endothelial cells plays a major role in determining which types of leucocytes are recruited. This allows for the preferential recirculation of subsets of T lymphocytes to specific organs, and also permits the selective recruitment of specific types of leucocytes during an inflammatory response.

The lymphocyte adhesion molecule integrin α4/β7 helps direct the migration (or ‘homing’) of lymphocytes to the intestine. α4/β7 is a receptor for mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1), a glycoprotein expressed on intestinal lamina propria venules and on high endothelial venules in Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes.3,4 MAdCAM-1 is not normally expressed at most extraintestinal sites,5,6 although it can be induced during inflammatory responses in the genital tract, the pancreas and the salivary glands.7–10 Studies performed with antibodies to α4/β7 or MAdCAM-1 or with β7-deficient mice clearly demonstrated that the α4/β7–MAdCAM-1 interaction plays a key role in the trafficking of lymphocytes to the intestine and associated lymphoid tissue.11–14

The expression of integrin α4/β7 on circulating T cells is heterogeneous.4,15 Naïve T cells, identified by their expression of CD45RA, generally express α4/β7 at a relatively low level. In contrast, CD45RA– memory/effector T cells can be divided into two subsets: α4/ and α4/β7–. The α4/

and α4/β7–. The α4/ memory/effector T cells preferentially recirculate through the intestine, whereas α4/β7– cells preferentially recirculate through other sites, including the periphery and the lung.16 Thus, the evidence suggests that a subset of T cells are ‘programmed’ to express high levels of α4/β7 and migrate preferentially to the intestine following primary activation. However, the factors that regulate α4/β7 expression on memory/effector T cells are not well known.

memory/effector T cells preferentially recirculate through the intestine, whereas α4/β7– cells preferentially recirculate through other sites, including the periphery and the lung.16 Thus, the evidence suggests that a subset of T cells are ‘programmed’ to express high levels of α4/β7 and migrate preferentially to the intestine following primary activation. However, the factors that regulate α4/β7 expression on memory/effector T cells are not well known.

Recent work indicates that the expression of certain T-lymphocyte adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors is influenced by some of the same factors that control the production of cytokines. Attention has focused largely on differences between cells producing type 1 cytokines [e.g. interferon-γ (IFN-γ)] and cells producing type 2 cytokines [e.g. interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-5]. For example, primary in vitro activation of CD4+ T cells under conditions that produce T helper type 1 (Th1) cells promoted the binding of cells to the endothelial ligands E- and P-selectin, whereas activation under Th2 conditions did not.17–19 This was associated with increased trafficking of Th1 cells to inflamed skin, where E- and P-selectin are expressed. Th1 and Th2 cells have also been reported to differ in the expression of several chemokine receptors.20–25 The existence of mechanisms for co-ordinate regulation of T-cell trafficking molecules and cytokine production may help to control the local balance between type 1 and type 2 cytokines during infection, allergy and autoimmune disease.

In this work, we explore the possibility that cytokine priming and the expression of integrin α4/β7 might be linked. This could help to control the delivery of T cells with specific cytokine-producing capabilities to the intestine and other sites of MAdCAM-1 expression. Our goals were: (1) to determine whether α4/ and α4/β7– memory/effector T cells from blood differ in their ability to produce cytokines; (2) to determine whether T cells that adhere to the α4/β7 ligand MAdCAM-1 differ from non-adherent cells in their ability to produce cytokines, and (3) to determine how in vitro primary activation of naïve T cells under Th1- versus Th2-promoting conditions influences expression of α4/β7.

and α4/β7– memory/effector T cells from blood differ in their ability to produce cytokines; (2) to determine whether T cells that adhere to the α4/β7 ligand MAdCAM-1 differ from non-adherent cells in their ability to produce cytokines, and (3) to determine how in vitro primary activation of naïve T cells under Th1- versus Th2-promoting conditions influences expression of α4/β7.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and cytokines

For identification of human T-cell subsets, CD4-allophycocyanin and CD8-allophycocyanin were obtained from Coulter (Miami, FL), and CD45RA-CyChrome was obtained from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). The following fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibodies were used for intracellular cytokine staining of human cells: anti-IL-2 (5344.111) and anti-TNF-α (6401.1111) from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA), and anti-IFN-γ (4S.B3) and anti-IL-4 (MP4-25D2) from Pharmingen. Isotype-matched control mouse and rat antibodies were purchased from Caltag (Burlingame, CA). For murine lymphocyte activation and polarization, murine recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2), rIL-4 and rIL-12 were obtained from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Unconjugated antibodies against mouse CD3e (145-2C11), CD28 (37.51), IFN-γ (XMG1.2) and IL-4 (BVD4-1D11) were obtained from Pharmingen. Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against murine IFN-γ (XMG1.2, FITC), integrin α4/β7 complex (DATK32, PE), integrin β7 subunit (FIB504, PE, recognizes both mouse and human β7) and l-selectin (MEL-14, FITC) were obtained from Pharmingen.

Human lymphocyte stimulation and staining

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from six normal adult donors (five male and one female, ages 30–41 years) using Vacutainer cell preparation tubes (Becton Dickinson) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were resuspended at 0·5 × 106−1 × 106/ml in a 1:1 mixture of autologous plasma and RPMI-1640. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 25 ng/ml, Sigma), ionomycin (1 µg/ml, Sigma), and Brefeldin A (10 µg/ml) were added and cells were incubated for 4 hr at 37°. Unstimulated cells (incubated with Brefeldin A alone) were used as controls. Cells were fixed in 2 ml FACS Lyse Solution (Becton Dickinson) for 10 min at room temperature, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0·1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) permeabilizing solution (Becton Dickinson) for an additional 10 min at room temperature. After an additional wash with PBS with 0·1% BSA, cells were incubated with allophycocyanin-conjugated CD4 or CD8 antibody, CyChrome-conjugated CD45RA, PE- conjugated anti-integrin β7 and FITC-conjugated antibody against IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, or tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for 30 min on ice. After washing, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and analysed by four-colour flow cytometry (FACScalibur, Becton Dickinson). Cells were also stained using isotype control antibodies, and these results were used to set thresholds used to calculate percentages of cytokine-producing cells. The University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research approved this study, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Adhesion assay

Recombinant soluble MAdCAM-1 (gift of Dr M. Briskin, LeukoSite, Cambridge, MA) and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) were used as ligands for in vitro adhesion assays. Six-well polystyrene plates (Corning, Corning, NY) were coated with ligand (6 µg in 3 ml PBS) for 18 hr at 4°, and then blocked by incubating with BSA for 1 hr at 37°. Other wells were coated with BSA alone as a control. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) were purified from PBMC by immunomagnetic negative selection using a CD14 MACS separation column (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PBL were resuspended in adhesion buffer (NaCl 150 mm, HEPES 10 mm, MnCl2 0·15 mm, pH 7·4) at 2 × 106 cells/ml. PBL were allowed to adhere at 37° for 20 min with gentle agitation. Non-adherent cells were collected and subjected to one or two additional rounds of panning on plates coated with the same ligand. Adherent cells were collected by incubating wells with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; 2 mm in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PBS) for 5 min. Non-adherent cells (remaining after two or three rounds of panning) and adherent cells were resuspended in PBS with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). In vitro stimulation (with PMA and ionomycin) and flow cytometric analysis were performed as described above.

Animals

DO11.10 T-cell receptor transgenic mice were bred and housed in a pathogen-free environment at the University of California San Francisco Animal Care Facility. These mice carry a transgene for a T-cell receptor that is specific for an ovalbumin-derived peptide (OVA323-339) presented by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) protein I-Ad.26,27 BALB/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The University of California San Francisco Committee on Animal Research approved this study.

In vitro activation of CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 T cell receptor-transgenic mice

For in vitro activation of DO11.10 CD4+ T cells, CD4+ T cells were purified from the spleens of DO11.10 mice by negative selection using an Isocell kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were ∼90% CD4+ as determined by flow cytometry. CD4+ T cells were activated using methods based on those described by other investigators.28,29 To activate cells with CD3 and CD28 antibodies, CD4+ T cells (0·3 × 105−2 × 105 cells/well), rIL-2 (10–50 units/ml) and soluble CD28 antibody (1–10 µg/ml) were added to 96-well plate wells that had been coated with CD3 antibody (50 µl of a 0·5–20 µg/ml solution). Alternatively, T cells were activated by co-incubating these cells with antigen-presenting cell (APC) loaded with the OVA323-339 peptide. A dendritic cell-rich APC population (∼20–40% CD11c+) was isolated from BALB/c mouse spleens using CD11c+ immunomagnetic selection. APC were treated with mitomycin C (5 µg/ml) at 37° for 30 min, pulsed with OVA323-339 (0·3–1·7 µm), and then co-cultured with CD4+ T cells (0·3 × 104−5·0 × 104 APC and 2 × 105 CD4+ T cells per well, in 24-well plates). Cells were activated in the presence of 3·5 ng/ml exogenous IL-12 plus 10 µg/ml neutralizing antibody against IL-4 (Th1-promoting conditions) or 500 U/ml exogenous IL-4 plus 10 µg/ml anti-IFN-γ (Th2-promoting conditions). Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 10 mm l-glutamine, 200 U/ml penicillin and 200 U/ml streptomycin.

In preliminary experiments, the effectiveness of Th1/Th2 polarization was assessed by re-stimulating cells with anti-CD3 8 days after primary activation and measuring IFN-γ and IL-4 production by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Caltag). Cells activated using Th1 conditions produced substantial amounts of IFN-γ (709 U/ml) but little IL-4 (4 ng/ml) after re-stimulation. Cells activated using Th2 conditions produced less IFN-γ (116 U/ml) but more IL-4 (78 ng/ml).

In vitro activation of naïve CD4+ T cells from BALB/c mice

BALB/c splenocytes were stained with antibodies against CD4 and l-selectin and sorted by flow cytometry (FACS Vantage, Becton Dickinson). Sorted cells were 99% CD4+ and 99% l-selectin+. Cells were activated using CD3 antibody (10 µg/ml coating concentration), CD28 antibody (1 µg/ml), and rIL-2 (20 ng/ml) under Th1 or Th2 conditions as described above.

Relationship of β7 expression and IFN-γ production following in vitro activation of murine CD4+ T cells

DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were activated using CD3 and CD28 antibodies as described above. Cells were collected 12 days after primary in vitro activation and re-stimulated with 5 ng/ml PMA (Sigma, Poole, UK) and 500 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma) in the presence of 10 µg/ml Brefeldin A (Sigma) for 4 hr. Cells were then incubated with PE-conjugated anti-β7 antibody, permeabilized with 0·1% saponin, stained with FITC-conjugated anti-IFN-γ antibody, and analysed by flow cytometry (FACSort, Becton Dickinson).

Expression of α4β7 following CD4+ T-cell activation under Th1- or Th2-promoting conditions

BALB/c naïve (l-selectin+) CD4+ T cells or DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were activated under Th1- or Th2-promoting conditions as described above. After 3–12 days in culture, cells were stained using DATK32 (anti-α4β7 antibody) or isotype control antibody and analysed by flow cytometry. For these experiments, cells were not re-stimulated with PMA and ionomycin.

Data analysis

Flow cytometry data were analysed using CellQuest (Becton Dickinson). Comparisons of cytokine production by  and β7– T cells were made using paired t-tests (InStat, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

and β7– T cells were made using paired t-tests (InStat, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Relationships between α4/β7 expression and cytokine production by human blood memory/effector T cells

The initial aim of our study was to determine whether α4/ and α4/β7– memory/effector T cells from blood differed in their ability to produce cytokines. Cytokine production was measured by intracellular cytokine staining following brief (4 hr) stimulation of human PBMC with PMA and ionomycin. Flow cytometry was used to simultaneously measure cytokine production and the expression of integrin β7. The anti-β7 antibody we used recognizes both α4/β7 and αE/β7. However, since very few blood T cells (∼1%) express αE/β7 (ref. 30 and data not shown), β7 staining is a reliable indicator of α4/β7 expression in these experiments. Antibodies against T-cell subset markers (CD45RA, expressed on naïve cells, and either CD4 or CD8) were also included in each flow cytometric analysis.

and α4/β7– memory/effector T cells from blood differed in their ability to produce cytokines. Cytokine production was measured by intracellular cytokine staining following brief (4 hr) stimulation of human PBMC with PMA and ionomycin. Flow cytometry was used to simultaneously measure cytokine production and the expression of integrin β7. The anti-β7 antibody we used recognizes both α4/β7 and αE/β7. However, since very few blood T cells (∼1%) express αE/β7 (ref. 30 and data not shown), β7 staining is a reliable indicator of α4/β7 expression in these experiments. Antibodies against T-cell subset markers (CD45RA, expressed on naïve cells, and either CD4 or CD8) were also included in each flow cytometric analysis.

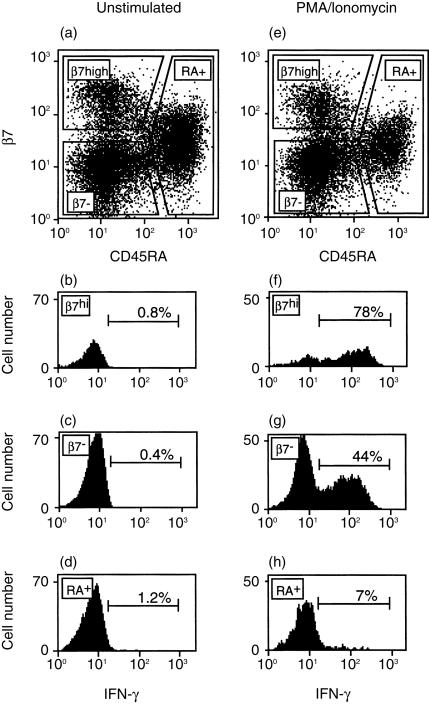

Figure 1 shows an analysis of IFN-γ production and β7 expression on human blood CD4+ T cells from one subject. In agreement with previous reports,4,15 CD4+ CD45RA– memory/effector T cells could be divided into  and β7– subsets, whereas CD45RA+ naïve cells expressed low-intermediate levels of β7 (Fig. 1a and e). As expected, there was little or no IFN-γ production detected in unstimulated T cells from any of these subsets (Fig. 1b–d). Stimulation with PMA and ionomycin resulted in increased IFN-γ production (Fig. 1f–h). Naïve cells (CD45RA+) produced IFN-γ at a relatively low frequency (7%). Among memory (CD45RA–) T cells from the subject analysed in Fig. 1, IFN-γ was produced by a large fraction of

and β7– subsets, whereas CD45RA+ naïve cells expressed low-intermediate levels of β7 (Fig. 1a and e). As expected, there was little or no IFN-γ production detected in unstimulated T cells from any of these subsets (Fig. 1b–d). Stimulation with PMA and ionomycin resulted in increased IFN-γ production (Fig. 1f–h). Naïve cells (CD45RA+) produced IFN-γ at a relatively low frequency (7%). Among memory (CD45RA–) T cells from the subject analysed in Fig. 1, IFN-γ was produced by a large fraction of  cells (78%) and by a smaller fraction (44%) of β7– cells. Analysis of data from a total of six subjects indicates that CD4+

cells (78%) and by a smaller fraction (44%) of β7– cells. Analysis of data from a total of six subjects indicates that CD4+  cells were more likely to produce IFN-γ than were β7– cells (Fig. 2a, P < 0·01 by paired t-test). In these six subjects, the fraction of CD4+

cells were more likely to produce IFN-γ than were β7– cells (Fig. 2a, P < 0·01 by paired t-test). In these six subjects, the fraction of CD4+  cells producing IFN-γ was 2·3 ± 0·5 (mean±SE) times larger than the fraction of β7– cells producing this cytokine.

cells producing IFN-γ was 2·3 ± 0·5 (mean±SE) times larger than the fraction of β7– cells producing this cytokine.

Figure 1.

Association between β7 expression and IFN-γ production by human CD4+ CD45RA– memory/effector T cells. Human PBMC were isolated and cultured for 4 hr without a stimulus (a–d), or in the presence of PMA and ionomycin (e–h). Expression of integrin β7 and CD45RA on unstimulated (a) and stimulated (e) CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were divided into CD45RA+ (naïve) and CD45RA– (memory/effector)  and β7– subsets, as shown. IFN-γ production was then determined for

and β7– subsets, as shown. IFN-γ production was then determined for  , β7– and CD45RA+ CD4+ T cells for the unstimulated (b–d) and stimulated (f–h) samples.

, β7– and CD45RA+ CD4+ T cells for the unstimulated (b–d) and stimulated (f–h) samples.

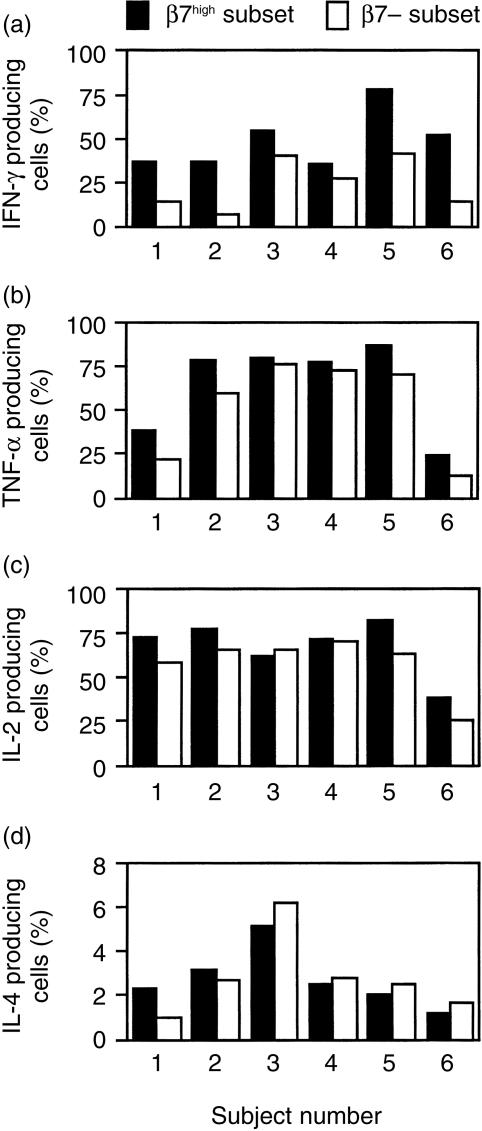

Figure 2.

Cytokine production by  and β7– human blood CD4+ CD45RA– T cells from six normal subjects. Production of the cytokines IFN-γ (a), TNF-α (b), IL-2 (c), and IL-4 (d) were measured by intracellular cytokine staining after 4 hr stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. The association between cytokine production and β7 expression on CD4+ CD45RA– T cells was determined using the approach outlined in Fig. 1.

and β7– human blood CD4+ CD45RA– T cells from six normal subjects. Production of the cytokines IFN-γ (a), TNF-α (b), IL-2 (c), and IL-4 (d) were measured by intracellular cytokine staining after 4 hr stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. The association between cytokine production and β7 expression on CD4+ CD45RA– T cells was determined using the approach outlined in Fig. 1.

We used the same approach to examine the association of β7 expression with the production of additional cytokines, and extended our analysis to include CD8+ T cells. For CD4+ CD45RA– T cells,  cells were more likely to produce TNF-α than were β7– cells (Fig. 2b, P < 0·01 by paired t-test). In the six subjects studied, the fraction of CD4+

cells were more likely to produce TNF-α than were β7– cells (Fig. 2b, P < 0·01 by paired t-test). In the six subjects studied, the fraction of CD4+  cells producing TNF-α was 1·4 ± 0·1 (mean ±SE) larger than the fraction of β7– cells producing this cytokine. For CD4+ CD45RA– T cells, there were no significant differences in the production of IL-2 or IL-4 by

cells producing TNF-α was 1·4 ± 0·1 (mean ±SE) larger than the fraction of β7– cells producing this cytokine. For CD4+ CD45RA– T cells, there were no significant differences in the production of IL-2 or IL-4 by  and β7– cells (Fig. 2c,d). Figure 3 shows results obtained when CD8+ CD45RA– T cells from the same six subjects were studied. Analysis of these results indicates that CD8+

and β7– cells (Fig. 2c,d). Figure 3 shows results obtained when CD8+ CD45RA– T cells from the same six subjects were studied. Analysis of these results indicates that CD8+  cells were more likely to produce IL-2 (Fig. 3c, P < 0·01) but less likely to produce TNF-α (Fig. 3b, P < 0·05) than were β7– cells. Among CD8+ cells, the fraction of

cells were more likely to produce IL-2 (Fig. 3c, P < 0·01) but less likely to produce TNF-α (Fig. 3b, P < 0·05) than were β7– cells. Among CD8+ cells, the fraction of  cells that produced IL-2 was 2·6 ± 0·6 times as large as the fraction of β7– cells that produced IL-2, and the fraction of

cells that produced IL-2 was 2·6 ± 0·6 times as large as the fraction of β7– cells that produced IL-2, and the fraction of  cells that produced TNF-α was 0·7 ± 0·1 times as large as the fraction of β7– cells that produced TNF-α. For CD8+ T cells, there were no significant differences in the production of IFN-γ or IL-4 by

cells that produced TNF-α was 0·7 ± 0·1 times as large as the fraction of β7– cells that produced TNF-α. For CD8+ T cells, there were no significant differences in the production of IFN-γ or IL-4 by  and β7– cells (Fig. 3a and d).

and β7– cells (Fig. 3a and d).

Figure 3.

Cytokine production by  and β7– human blood CD8+ CD45RA– T cells from six normal subjects. The experimental protocol and analysis were performed in the same manner as described in Figs 1 and 2, except that a CD8 antibody was used for staining cells (instead of a CD4 antibody). Columns labelled ‘0’ indicate that no cytokine production was detected for these subsets.

and β7– human blood CD8+ CD45RA– T cells from six normal subjects. The experimental protocol and analysis were performed in the same manner as described in Figs 1 and 2, except that a CD8 antibody was used for staining cells (instead of a CD4 antibody). Columns labelled ‘0’ indicate that no cytokine production was detected for these subsets.

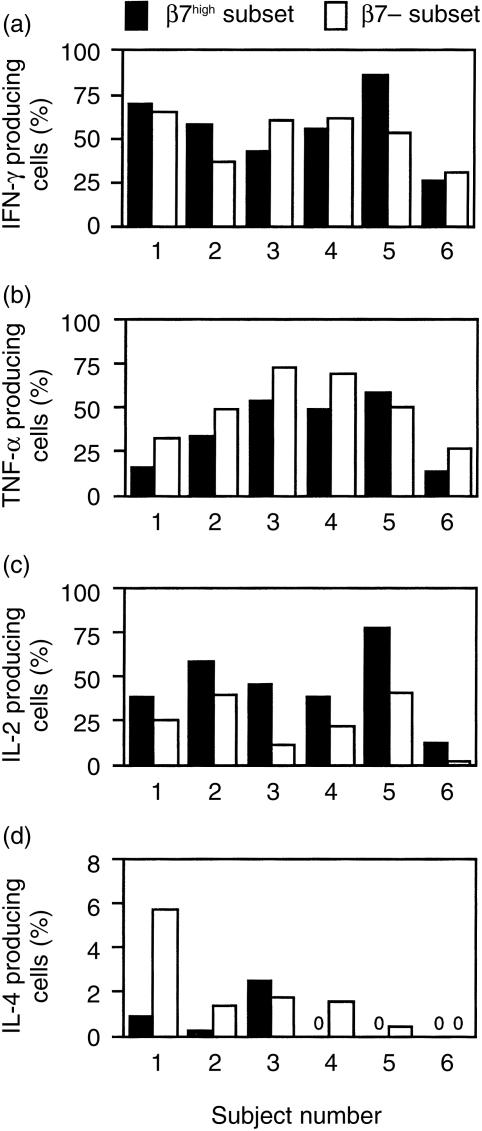

Selective adhesion of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells to MAdCAM-1

The finding of an association between IFN-γ production and integrin α4/β7 expression by CD4+ T cells suggests that IFN-γ-producing cells might be preferentially recruited to sites where the α4/β7 ligand MAdCAM-1 is expressed. We used an in vitro adhesion assay to directly determine whether MAdCAM-1-adherent human blood CD4+ memory/effector T cells produced IFN-γ at a different frequency than non-adherent cells. After panning on MAdCAM-1-coated plates, adherent and non-adherent cells were stimulated for 4 hr with PMA and ionomycin, and IFN-γ production was determined by intracellular cytokine staining. CD4+ CD45RA– T cells that adhered to MAdCAM-1 were more likely to produce IFN-γ than were non-adherent cells in all four experiments performed (Fig. 4a,b and data not shown). In comparison, when ICAM-1 (a ligand for integrin αLβ2) was used, IFN-γ production by adherent and non-adherent cells was similar (Fig. 4c,d). As expected, adhesion to MAdCAM-1 greatly enriched for α4/ cells (Fig. 4e,f), but adhesion to ICAM-1 did not (Fig. 4g,h). Some α4/β7– cells did adhere to MAdCAM-1-coated plates (Fig. 4e). Many or all or these cells are likely to represent non-specifically adherent cells, since there was some adhesion of cells to plates coated with BSA alone. IFN-γ production was similar for BSA-adherent (41% IFN-γ+) and non-adherent (42% IFN-γ+) cells, indicating that non-specific adhesion did not contribute to the preferential production of IFN-γ by cells adhering to MAdCAM-1-coated plates.

cells (Fig. 4e,f), but adhesion to ICAM-1 did not (Fig. 4g,h). Some α4/β7– cells did adhere to MAdCAM-1-coated plates (Fig. 4e). Many or all or these cells are likely to represent non-specifically adherent cells, since there was some adhesion of cells to plates coated with BSA alone. IFN-γ production was similar for BSA-adherent (41% IFN-γ+) and non-adherent (42% IFN-γ+) cells, indicating that non-specific adhesion did not contribute to the preferential production of IFN-γ by cells adhering to MAdCAM-1-coated plates.

Figure 4.

Preferential production of IFN-γ by MAdCAM-1-adherent CD4+ memory/effector T cells. Human PBL were allowed to adhere to MAdCAM-1- or ICAM-1-coated plates, and adherent and non-adherent populations were treated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hr to stimulate cytokine production. IFN-γ production by CD4+ CD45RA– T cells was analysed by intracellular cytokine staining of (a) MAdCAM-1-adherent, (b) MAdCAM-1-non-adherent, (c) ICAM-1-adherent and (d) ICAM-1-non-adherent populations. The expression of β7 on CD4+ CD45RA– T cells in these populations was also analysed by flow cytometry (e–h).

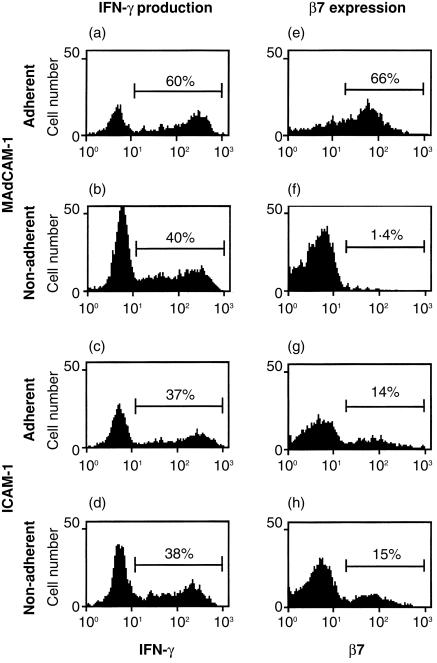

Association of β7 expression and IFN-γ production following in vitro activation of mouse CD4+ T cells

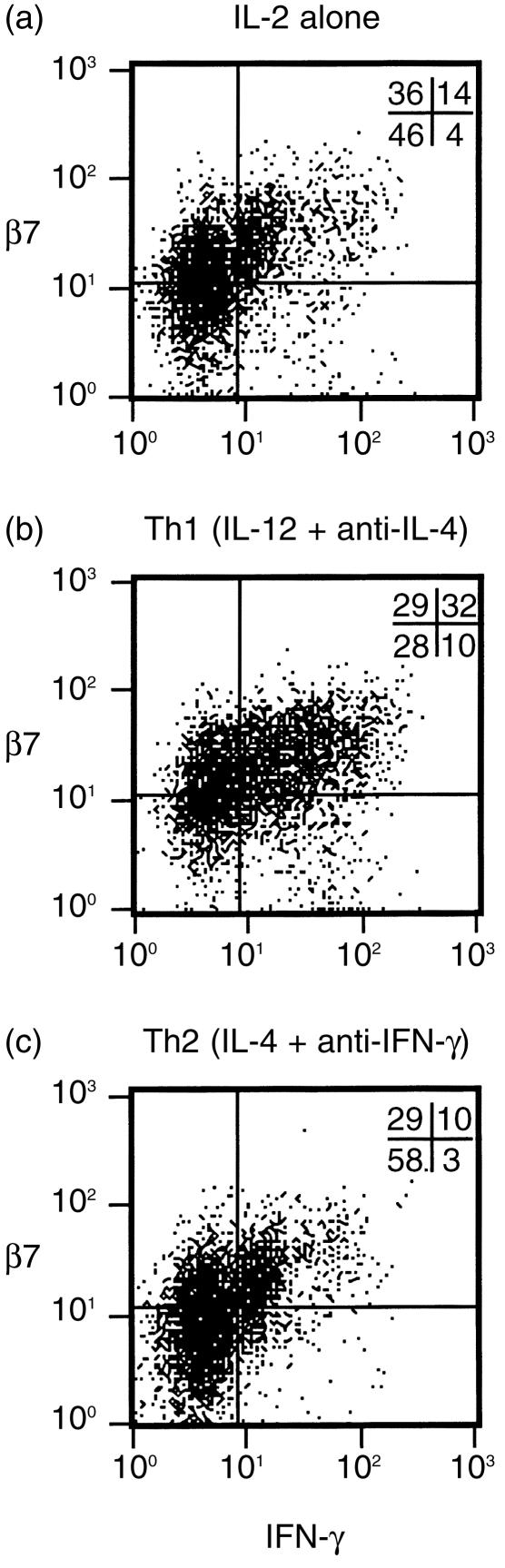

Our analysis of human blood CD4+ memory/effector T cells revealed the preferential production of the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ by  cells. One possible explanation for this result is that factors that promote Th1 differentiation at the time of activation of CD4+ T cells might also promote expression of α4/β7. We studied the effects of Th1/Th2 polarization on α4/β7 expression following in vitro activation of mouse T cells. We first determined whether CD4+ T cells activated in this system would exhibit the same association between α4/β7 expression and IFN-γ production as seen in the human experiments. For this experiment, CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 T-cell receptor transgenic mice were activated using anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies and supplemental IL-2. Exogenous IL-12 and anti-IL-4 were added to promote Th1 polarization, or exogenous IL-4 and anti-IFN-γ were added to promote Th2 polarization. We used flow cytometry to directly compare IFN-γ production in

cells. One possible explanation for this result is that factors that promote Th1 differentiation at the time of activation of CD4+ T cells might also promote expression of α4/β7. We studied the effects of Th1/Th2 polarization on α4/β7 expression following in vitro activation of mouse T cells. We first determined whether CD4+ T cells activated in this system would exhibit the same association between α4/β7 expression and IFN-γ production as seen in the human experiments. For this experiment, CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 T-cell receptor transgenic mice were activated using anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies and supplemental IL-2. Exogenous IL-12 and anti-IL-4 were added to promote Th1 polarization, or exogenous IL-4 and anti-IFN-γ were added to promote Th2 polarization. We used flow cytometry to directly compare IFN-γ production in  and β7– murine CD4+ T cells harvested 12 days after primary in vitro activation. These cells (like human blood T cells) produced little IFN-γ spontaneously (not shown) but did produce easily detectable amounts of IFN-γ after 4 hr treatment with PMA and ionomycin (Fig. 5). Many cells (42%) activated under Th1-promoting conditions produced IFN-γ. As expected, cells activated without exogenous polarizing cytokines (IL-2 alone) or under Th2-promoting conditions produced IFN-γ less frequently (18% and 13%, respectively). High β7 expression was more common on cells activated under Th1-promoting conditions (60%) than on cells activated using IL-2 alone (50%) or Th2-promoting conditions (39%). In all three conditions, 76–78% of IFN-γ-producing cells expressed β7 at high levels. In contrast, only 33–51% of cells that did not produce detectable amounts of IFN-γ expressed β7 at high levels.

and β7– murine CD4+ T cells harvested 12 days after primary in vitro activation. These cells (like human blood T cells) produced little IFN-γ spontaneously (not shown) but did produce easily detectable amounts of IFN-γ after 4 hr treatment with PMA and ionomycin (Fig. 5). Many cells (42%) activated under Th1-promoting conditions produced IFN-γ. As expected, cells activated without exogenous polarizing cytokines (IL-2 alone) or under Th2-promoting conditions produced IFN-γ less frequently (18% and 13%, respectively). High β7 expression was more common on cells activated under Th1-promoting conditions (60%) than on cells activated using IL-2 alone (50%) or Th2-promoting conditions (39%). In all three conditions, 76–78% of IFN-γ-producing cells expressed β7 at high levels. In contrast, only 33–51% of cells that did not produce detectable amounts of IFN-γ expressed β7 at high levels.

Figure 5.

Association between β7 expression and IFN-γ production by mouse CD4+ T cells activated and polarized in vitro. CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 T-cell receptor-transgenic mice were activated using anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 in the presence of IL-2 alone (a), or in combination with exogenous IL-12 plus anti-IL-4 antibody (Th1 conditions) (b) or exogenous IL-4 plus anti-IFN-γ (Th2 conditions) (c). After 12 days, cells were re-stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hr and β7 integrin expression and IFN-γ production were analysed by flow cytometry (see Materials and Methods). The percentage of cells in each quadrant is shown at the upper right corner of each plot. Quadrant positions were established based on staining with isotype control antibodies (99% of cells were in the lower left quadrant when control antibodies were used for staining, not shown).

Primary activation of naïve mouse CD4+ T cells under Th1 polarizing conditions favours expression of integrin α4/β7

We extended our analysis of the effects of Th1/Th2 polarization during in vitro activation in additional experiments. In these experiments, CD4+ splenocytes, isolated from DO11.10 mice, were activated using either anti-CD3 and CD28 antibodies or ovalbumin peptide and APC. A range of antibody and peptide concentrations was used (see Materials and Methods). For each comparison, two samples of cells were activated using the same stimuli, except that IL-12 and anti-IL-4 were included in one sample (Th1 sample) and IL-4 and anti-IFN-γ were included in the other (Th2 sample). α4/β7 expression was measured 8–12 days after activation, using the α4/β7-specific antibody DATK32. Since the goal of these experiments was to determine the effects of polarization at the time of activation, the cells were not re-stimulated prior to analysis (and intracellular cytokine staining was not performed). We found that α4/β7 expression, as measured by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) after staining with the DATK32 antibody, was higher on cells in the Th1 sample in 28 of the 30 paired samples analysed. Expression of α4/β7 was significantly higher following Th1 polarization when activation was accomplished with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (MFI 146 ± 31 versus 50 ± 11; mean±SD, P < 0·01 by paired t-test) or with ovalbumin and APC (MFI 112 ± 20 versus 68 ± 14, P < 0·0001). These results suggest that activation of CD4+ T cells under Th1-promoting conditions favours α4/β7 expression. Alternatively, the results might be explained by the preferential proliferation or survival of the α4/ subset of memory/effector T cells present in the starting T-cell population under these conditions.

subset of memory/effector T cells present in the starting T-cell population under these conditions.

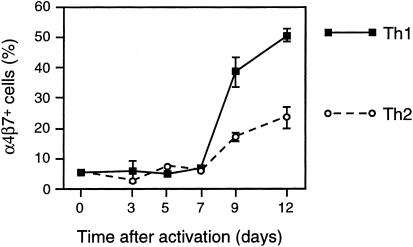

We performed an additional experiment to determine directly the effects of Th1/Th2 polarization on α4/β7 expression following primary in vitro activation of naïve CD4+ T cells. For this experiment, BALB/c naïve CD4+ splenocytes (99% l-selectin+) were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 under Th1- or Th2-promoting conditions. Expression of α4/β7 was measured before activation and at 3, 5, 7, 9 and 12 days after activation (Fig. 6). For both Th1- and Th2-promoting conditions, α4/β7 expression remained low over the first 7 days following activation but increased thereafter. At these later time-points, α4/β7 expression was greater for cells activated under Th1-promoting conditions. These results indicate that primary activation of naïve CD4+ T cells under Th1-promoting conditions favours α4/β7 expression.

Figure 6.

α4/β7 expression following primary in vitro activation and polarization of naive mouse CD4+ T cells under Th1- and Th2-promoting conditions. Naïve T cells (99% CD4+, 99% l-selectin+) were purified from spleens of BALB/c mice and activated under Th1- or Th2-promoting conditions (see Materials and Methods). Before activation and at 3, 5, 7, 9 and 12 days after activation, duplicate samples were stained with DATK32 antibody (anti-α4/β7) and analysed by flow cytometry. The mean percentage of α4/β7+ cells is shown at each time-point. Error bars represent standard deviations of duplicate samples. In all cases, ≤ 1% of cells were stained with an isotype control antibody.

Discussion

The studies reported here were designed to identify possible associations between the expression of integrin α4/β7 and the production of specific cytokines by T lymphocytes. We began by studying T cells from human blood. We chose to measure cytokine production using intracellular cytokine staining rather than measuring cytokine secretion from purified subsets of  and β7– cells. With the intracellular cytokine staining approach, all cells were stimulated under identical conditions and with as little manipulation as possible. This method allowed us to relate cytokine production directly to α4/β7 expression on individual cells belonging to different T-cell subsets. When CD4+ CD45RA– memory/effector T cells were analysed, we found that α4/

and β7– cells. With the intracellular cytokine staining approach, all cells were stimulated under identical conditions and with as little manipulation as possible. This method allowed us to relate cytokine production directly to α4/β7 expression on individual cells belonging to different T-cell subsets. When CD4+ CD45RA– memory/effector T cells were analysed, we found that α4/ cells were significantly more likely to produce IFN-γ and TNF-α following 4 hr stimulation with PMA and ionomycin than were α4/β7– cells (Figs 1 and 2). When CD8+ CD45RA– cells were analysed, we found that α4/

cells were significantly more likely to produce IFN-γ and TNF-α following 4 hr stimulation with PMA and ionomycin than were α4/β7– cells (Figs 1 and 2). When CD8+ CD45RA– cells were analysed, we found that α4/ cells were more likely to produce IL-2 compared with α4/β7– cells, but less likely to produce TNF-α (Fig. 3). For both CD4+ CD45RA– and CD8+ CD45RA– T cells, there were no significant differences in IL-4-producing cells between α4/

cells were more likely to produce IL-2 compared with α4/β7– cells, but less likely to produce TNF-α (Fig. 3). For both CD4+ CD45RA– and CD8+ CD45RA– T cells, there were no significant differences in IL-4-producing cells between α4/ and α4/β7– cells (Figs 2 and 3). These data demonstrate that there are differences in cytokine production between α4/

and α4/β7– cells (Figs 2 and 3). These data demonstrate that there are differences in cytokine production between α4/ and α4/β7– human blood memory/effector T cells.

and α4/β7– human blood memory/effector T cells.

The association between α4/β7 expression and IFN-γ production suggests a link between homing and cytokine production. However, the level of expression of α4/β7 does not always predict the ability of a cell to adhere to the α4/β7 ligand MAdCAM-1.4 We used an in vitro cell adhesion assay to compare MAdCAM-1-adherent and non-adherent CD4+ memory/effector T cells directly. Adhesion to MAdCAM-1 did enrich for CD4+ T cells that produced IFN-γ following brief stimulation, whereas adhesion to plates coated with ICAM-1, a ligand for a different integrin (αLβ2) did not (Fig. 4a–d). The most likely explanation for these results is that MAdCAM-1 selectively promotes binding of α4/ cells, which produce IFN-γ at a higher frequency than α4/β7– cells. Consistent with this explanation, adhesion to MAdCAM-1 did substantially enrich for α4/

cells, which produce IFN-γ at a higher frequency than α4/β7– cells. Consistent with this explanation, adhesion to MAdCAM-1 did substantially enrich for α4/ cells, whereas adhesion to ICAM-1 did not (Fig. 4e–h). We conclude that CD4+ memory/effector T cells that bind to MAdCAM-1 are preferentially primed to produce IFN-γ.

cells, whereas adhesion to ICAM-1 did not (Fig. 4e–h). We conclude that CD4+ memory/effector T cells that bind to MAdCAM-1 are preferentially primed to produce IFN-γ.

The strongest association that we identified in our studies of human blood CD4+ memory/effector cells was the association between α4/β7 expression and the production of IFN-γ, a cytokine that is characteristically produced by Th1 cells. This led us to investigate the possibility that primary T-cell activation conditions that favour Th1 polarization might lead to higher expression of α4/β7. We directly tested this possibility by activating murine CD4+ splenocytes under conditions that promote Th1 or Th2 polarization. For initial experiments, we chose to use CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 T-cell receptor-transgenic mice, since protocols for primary activation of T cells from these mice with either anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies or with antigen (ovalbumin) presented by APC are well established.28,29 Twelve days after primary activation, using the same approach we employed with the human PBMCs, we stimulated the cells with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hr and then measured β7 expression and IFN-γ production by flow cytometry. We found that  cells produced by in vitro T-cell activation were more likely to express IFN-γ than were β7– cells, a finding similar to that obtained in our studies of human blood memory/effector T cells (Fig. 5). Additional studies involving a range of primary activation conditions confirmed that cells activated under Th1-polarizing conditions expressed significantly higher levels of α4/β7 than did cells activated under Th2-promoting conditions at 8–12 days after activation. To rigorously examine the kinetics of α4/β7 expression after primary in vitro activation of naïve CD4+ T cells under Th1- and Th2-promoting conditions, we purified naïve (l-selectin+) cells and measured α4/β7 expression at various time-points after activation (Fig. 6). We found that α4/β7 expression remained low up to day 7, but increased by day 9. Expression of α4/β7 at days 9 and 12 was substantially greater when cells were activated under Th1-promoting conditions. These findings suggest some relationship between mechanisms that control Th1 cytokine expression and those that control α4/β7 expression. However, as there are cells that express α4/β7 but do not produce IFN-γ, or produce IFN-γ but do not express α4/β7, there must be other factors that are also important in regulating α4/β7 expression after primary activation of CD4+ T cells.

cells produced by in vitro T-cell activation were more likely to express IFN-γ than were β7– cells, a finding similar to that obtained in our studies of human blood memory/effector T cells (Fig. 5). Additional studies involving a range of primary activation conditions confirmed that cells activated under Th1-polarizing conditions expressed significantly higher levels of α4/β7 than did cells activated under Th2-promoting conditions at 8–12 days after activation. To rigorously examine the kinetics of α4/β7 expression after primary in vitro activation of naïve CD4+ T cells under Th1- and Th2-promoting conditions, we purified naïve (l-selectin+) cells and measured α4/β7 expression at various time-points after activation (Fig. 6). We found that α4/β7 expression remained low up to day 7, but increased by day 9. Expression of α4/β7 at days 9 and 12 was substantially greater when cells were activated under Th1-promoting conditions. These findings suggest some relationship between mechanisms that control Th1 cytokine expression and those that control α4/β7 expression. However, as there are cells that express α4/β7 but do not produce IFN-γ, or produce IFN-γ but do not express α4/β7, there must be other factors that are also important in regulating α4/β7 expression after primary activation of CD4+ T cells.

These results suggest that the induction of MAdCAM-1 during an inflammatory response might favour recruitment of IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells. MAdCAM-1 expression on intestinal venules is increased in a variety of inflammatory states, including Crohn's disease and animal models of inflammatory bowel disease.6,31,32 IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells appear to be especially important in the pathogenesis of these diseases.33–35 MAdCAM-1 can also be expressed at some extraintestinal inflammatory sites, such as the pancreatic islet venules of diabetic mice7,10,36 or the genital mucosal venules of mice infected with Chlamydia trachomatis.9 In these extraintestinal inflammatory conditions, MAdCAM-1 expression is also associated with the infiltration of α4/ T cells and the development of a local Th1 response.9,37 Based on these results we speculate that MAdCAM-1 expression could contribute to the selective recruitment of Th1 cells in certain inflammatory states, but further studies will be required to directly examine this possibility.

T cells and the development of a local Th1 response.9,37 Based on these results we speculate that MAdCAM-1 expression could contribute to the selective recruitment of Th1 cells in certain inflammatory states, but further studies will be required to directly examine this possibility.

This work should be considered in light of recent studies focusing on relationships between Th1/Th2 polarization and expression of several molecules involved in T-lymphocyte trafficking, including other adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors. Some studies have focused on the relationship between Th1/Th2 polarization and the expression of E- and P-selectin ligands, adhesion molecules that are important for the trafficking of T cells to sites of inflammation in the skin and some other sites. Mouse Th1 cells, produced by in vitro activation, were found to bind to the endothelial ligands E- and P-selectin, whereas Th2 cells did not.17,18 However, no relationship was found between E-selectin binding and the production of cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-2, or IL-4) by human blood CD4+ memory T cells.38,39 There was also no relationship between P-selectin binding and IFN-γ production on T cells isolated from inflamed colon in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease.40 Chemokine receptors found to be preferentially expressed on Th1 cells include CXCR3, CCR5 and CCR7, whereas Th2 cells have been reported to preferentially express CCR3, CCR4, CCR8 and CXCR4.20–24 Recently, some chemokine receptors have been shown to be differentially expressed on α4/ T cells.41–46 In some cases, associations between Th1/Th2 polarization and adhesion receptor or chemokine receptor expression that were observed using in vitro activated cells were also seen in vivo, but not in other cases.25 In our studies, we found an association between α4/β7 expression and priming for IFN-γ production both for mouse CD4+ T cells activated in vitro and for CD4+ T cells that had undergone primary activation in vivo (human blood memory/effector cells). Taken together, available data indicate that regulation of Th1/Th2 differentiation and the expression of several molecules that control T-cell migration are co-ordinated in some situations. The molecular mechanisms that allow for this co-ordination are not yet known.

T cells.41–46 In some cases, associations between Th1/Th2 polarization and adhesion receptor or chemokine receptor expression that were observed using in vitro activated cells were also seen in vivo, but not in other cases.25 In our studies, we found an association between α4/β7 expression and priming for IFN-γ production both for mouse CD4+ T cells activated in vitro and for CD4+ T cells that had undergone primary activation in vivo (human blood memory/effector cells). Taken together, available data indicate that regulation of Th1/Th2 differentiation and the expression of several molecules that control T-cell migration are co-ordinated in some situations. The molecular mechanisms that allow for this co-ordination are not yet known.

In summary, the studies described here indicate that human blood α4/ and α4/β7– memory/effector T cells differ in their ability to produce certain cytokines following short-term stimulation. Most notably, we found that α4/

and α4/β7– memory/effector T cells differ in their ability to produce certain cytokines following short-term stimulation. Most notably, we found that α4/ CD4+ T cells were more likely to produce the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ. The association between α4/β7 and IFN-γ is likely to be functionally important, since we found that cells that adhered to the α4/β7 ligand MAdCAM-1 produced IFN-γ at a higher frequency than non-adherent cells. We also found an association between Th1 polarization and α4/β7 expression on mouse CD4+ T cells that had undergone primary activation in vitro. Relationships between α4/β7 expression and cytokine production might help to determine the cytokine balance when MAdCAM-1 is expressed at sites of inflammation in the intestine or elsewhere.

CD4+ T cells were more likely to produce the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ. The association between α4/β7 and IFN-γ is likely to be functionally important, since we found that cells that adhered to the α4/β7 ligand MAdCAM-1 produced IFN-γ at a higher frequency than non-adherent cells. We also found an association between Th1 polarization and α4/β7 expression on mouse CD4+ T cells that had undergone primary activation in vitro. Relationships between α4/β7 expression and cytokine production might help to determine the cytokine balance when MAdCAM-1 is expressed at sites of inflammation in the intestine or elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH R01 grants DK54212 and HL50024. Dr Abramson received training grant support from the NIH (T32-DK07762). We thank the staff of the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology at UCSF for their assistance and training, Madeleine Willkom for her excellent technical assistance, and members of the Erle laboratory for comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- MAdCAM-1

mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- Th1

T helper type 1

- Th2

T helper type 2

References

- 1.Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–6. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butcher EC, Williams M, Youngman K, Rott L, Briskin M. Lymphocyte trafficking and regional immunity. Adv Immunol. 1999;72:209–53. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlin C, Berg EL, Briskin MJ, et al. α4β7 integrin mediates lymphocyte binding to the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM-1. Cell. 1993;74:185–5. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90305-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erle DJ, Briskin MJ, Butcher EC, Garcia-Pardo A, Lazarovits AI, Tidswell M. Expression and function of the MAdCAM-1 receptor, integrin α4β7, on human leukocytes. J Immunol. 1994;153:517–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Streeter PR, Berg EL, Rouse BT, Bargatze RF, Butcher EC. A tissue-specific endothelial cell molecule involved in lymphocyte homing. Nature. 1988;331:41–6. doi: 10.1038/331041a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briskin M, Winsor-Hines D, Shyjan A, et al. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is preferentially expressed in intestinal tract and associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faveeuw C, Gagnerault MC, Lepault F. Expression of homing and adhesion molecules in infiltrated islets of Langerhans and salivary glands of nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 1994;152:5969–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanninen A, Salmi M, Simell O, Andrew D, Jalkanen S. Recirculation and homing of lymphocyte subsets: dual homing specificity of beta 7-integrin (high) -lymphocytes in nonobese diabetic mice. Blood. 1996;88:934–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly KA, Rank RG. Identification of homing receptors that mediate the recruitment of CD4 T cells to the genital tract following intravaginal infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5198–208. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5198-5208.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang XD, Michie SA, Mebius RE, Tisch R, Weissman I, McDevitt HO. The role of cell adhesion molecules in the development of IDDM. implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Diabetes. 1996;45:705–10. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.6.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamann A, Andrew DP, Jablonski-Westrich D, Holzmann B, Butcher EC. Role of α4-integrins in lymphocyte homing to mucosal tissues in vivo. J Immunol. 1994;152:3282–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hesterberg PE, Winsor-Hines D, Briskin MJ, Soler-Ferran D, Merrill C, Mackay CR, Newman W, Ringler DJ. Rapid resolution of chronic colitis in the cotton-top tamarin with an antibody to a gut-homing integrin α4β7. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1373–80. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picarella D, Hurlbut P, Rottman J, Shi X, Butcher E, Ringler DJ. Monoclonal antibodies specific for β7 integrin and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) reduce inflammation in the colon of scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:2099–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner N, Lohler J, Kunkel EJ, Ley K, Leung E, Krissansen G, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Critical role for β7 integrins in formation of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Nature. 1996;382:366–70. doi: 10.1038/382366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schweighoffer T, Tanaka Y, Tidswell M, et al. Selective expression of integrin α4β7 on a subset of human CD4+ memory T cells with hallmarks of gut-trophism. J Immunol. 1993;151:717–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abitorabi MA, Mackay CR, Jerome EH, Osorio O, Butcher EC, Erle DJ. Differential expression of homing molecules on recirculating lymphocytes from sheep gut, peripheral, and lung lymph. J Immunol. 1996;156:3111–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austrup F, Vestweber D, Borges E, et al. P- and E-selectin mediate recruitment of T-helper-1 but not T-helper-2 cells into inflamed tissues. Nature. 1997;385:81–3. doi: 10.1038/385081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borges E, Tietz W, Steegmaier M, Moll T, Hallmann R, Hamann A, Vestweber D. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) on T helper 1 but not on T helper 2 cells binds to P-selectin and supports migration into inflamed skin. J Exp Med. 1997;185:573–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syrbe U, Siveke J, Hamann A. Th1/Th2 subsets: distinct differences in homing and chemokine receptor expression? Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1999;21:263–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00812257. 10.1007/s002810050067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallusto F, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. Selective expression of the eotaxin receptor CCR3 by human T helper 2 cells. Science. 1997;277:2005–7. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2005. 10.1126/science.277.5334.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. Flexible programs of chemokine receptor expression on human polarized T helper 1 and 2 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:875–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonecchi R, Bianchi G, Bordignon PP, et al. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and chemotactic responsiveness of type 1 T helper cells (Th1s) and Th2s. J Exp Med. 1998;187:129–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zingoni A, Soto H, Hedrick JA, et al. The chemokine receptor CCR8 is preferentially expressed in Th2 but not Th1 cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:547–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randolph DA, Huang G, Carruthers CJ, Bromley LE, Chaplin DD. The role of CCR7 in TH1 and TH2 cell localization and delivery of B cell help in vivo. Science. 1999;286:2159–62. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2159. 10.1126/science.286.5447.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Galli G, Beltrame C, Romagnani P, Manetti R, Romagnani S, Maggi E. Assessment of chemokine receptor expression by human Th1 and Th2 cells in vitro and in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:691–9. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy KM, Heimberger AB, Loh DY. Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+CD8+TCRlo thymocytes in vivo. Science. 1990;250:1720–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh CS, Heimberger AB, Gold JS, O'Garra A, Murphy KM. Differential regulation of T helper phenotype development by interleukins 4 and 10 in an αβ T-cell-receptor transgenic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6065–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swain SL. Generation and in vivo persistence of polarized Th1 and Th2 memory cells. Immunity. 1994;1:543–52. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosken NA, Shibuya K, Heath AW, Murphy KM, O'Garra A. The effect of antigen dose on CD4+ T helper cell phenotype development in a T cell receptor-αβ-transgenic model. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1579–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erle DJ, Brown T, Christian D, Aris R. Lung epithelial lining fluid T cell subsets defined by distinct patterns of β7 and β1 integrin expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:237–44. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.3.7509610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Souza HS, Elia CC, Spencer J, MacDonald TT. Expression of lymphocyte-endothelial receptor-ligand pairs, α4β7/MAdCAM-1 and OX40/OX40 ligand in the colon and jejunum of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1999;45:856–63. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Winter H, Cheroutre H, Kronenberg M. Mucosal immunity and inflammation. II. The yin and yang of T cells in intestinal inflammation: pathogenic and protective roles in a mouse colitis model. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1317–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.6.G1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacDermott RP. Alterations in the mucosal immune system in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Med Clin North Am. 1994;78:1207–31. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuss IJ, Neurath M, Boirivant M, Klein JS, de la Motte C, Strong SA, Fiocchi C, Strober W. Disparate CD4+ lamina propria (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn's disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-γ, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J Immunol. 1996;157:1261–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumberg RS, Saubermann LJ, Strober W. Animal models of mucosal inflammation and their relation to human inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:648–56. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00032-1. 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanninen A, Salmi M, Simell O, Jalkanen S. Mucosa-associated (β7-integrinhigh) lymphocytes accumulate early in the pancreas of NOD mice and show aberrant recirculation behavior. Diabetes. 1996;45:1173–80. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.9.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liblau RS, Singer SM, McDevitt HO. Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis of organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Immunol Today. 1995;16:34–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teraki Y, Picker LJ. Independent regulation of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen expression and cytokine synthesis phenotype during human CD4+ memory T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 1997;159:6018–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akdis M, Akdis CA, Weigl L, Disch R, Blaser K. Skin-homing, CLA+ memory T cells are activated in atopic dermatitis and regulate IgE by an IL-13-dominated cytokine pattern: IgG4 counter-regulation by CLA– memory T cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:4611–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu A, Hong K, Berg EL, Ehrhardt RO. Tissue specificity of E- and P-selectin ligands in Th1-mediated chronic inflammation. J Immunol. 1999;163:5086–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell JJ, Haraldsen G, Pan J, et al. The chemokine receptor CCR4 in vascular recognition by cutaneous but not intestinal memory T cells. Nature. 1999;400:776–80. doi: 10.1038/23495. 10.1038/23495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao F, Rabin RL, Smith CS, Sharma G, Nutman TB, Farber JM. CC-chemokine receptor 6 is expressed on diverse memory subsets of T cells and determines responsiveness to macrophage inflammatory protein 3 alpha. J Immunol. 1999;162:186–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zabel BA, Agace WW, Campbell JJ, et al. Human G protein-coupled receptor GPR-9-6/CC chemokine receptor 9 is selectively expressed on intestinal homing T lymphocytes, mucosal lymphocytes, and thymocytes and is required for thymus-expressed chemokine-mediated chemotaxis. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1241–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agace WW, Roberts AI, Wu L, Greineder C, Ebert EC, Parker CM. Human intestinal lamina propria and intraepithelial lymphocytes express receptors specific for chemokines induced by inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:819–26. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200003)30:3<819::AID-IMMU819>3.0.CO;2-Y. 10.1002/(sici)1521-4141(200003)30:03<819::aid-immu819>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kunkel EJ, Campbell JJ, Haraldsen G, et al. Lymphocyte CC chemokine receptor 9 and epithelial thymus-expressed chemokine (TECK) expression distinguish the small intestinal immune compartment: Epithelial expression of tissue-specific chemokines as an organizing principle in regional immunity. J Exp Med. 2000;192:761–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papadakis KA, Prehn J, Nelson V, Cheng L, Binder SW, Ponath PD, Andrew DP, Targan SR. The role of thymus-expressed chemokine and its receptor CCR9 on lymphocytes in the regional specialization of the mucosal immune system. J Immunol. 2000;165:5069–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]