Abstract

Stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) is a chemokine abundantly expressed in the thymus. However, a potential role of SDF-1α in the thymus has been under consideration, since no appreciable difference was detected in the migratory responsiveness to the SDF-1α between cortical and medullary thymocytes. In the present study, we examined the effects of extracellular matrix (ECM) on the responsiveness of murine thymocytes to several chemokines including SDF-1α. In the absence of ECM, chemotactic activity of SDF-1α for cortical (CD4/8 double-positive) thymocytes was almost same as that for medullary (CD4 or CD8 single-positive) thymocytes. In contrast, the chemotactic activity of SDF-1α for cortical thymocytes was considerably (more than 10-fold) enhanced by laminin or fibronectin as compared with that for medullary thymocytes. Chemotactic activities of macrophage-derived chemokine and macrophage inflammatory protein-3β for both cortical and medullary thymocytes were only slightly enhanced by fibronectin or laminin. Thus, fibronectin and laminin appear to enhance the chemotactic activity of SDF-1α for cortical thymocytes selectively. Addition of a monoclonal antibody against CD29 showed no inhibitory effect on the enhanced chemotactic activity of SDF-1α, suggesting that the other unknown receptor(s) is involved in this enhancement. Our present data demonstrate that SDF-1α in the presence of fibronectin or laminin is involved in the distribution of developing thymocytes.

Introduction

Chemokines are small proteins with molecular weights around 10 000 which regulate the migration of leucocytes.1–5 The chemokines constitute at least four subfamilies (CXC, CC, C and CX3C) depending on the number of cysteines and the space between the first two cysteines. These chemokines bind G-protein-coupled receptors with seven transmembrane domains.6–8 It seems that chemokines regulate movements and distribution of the corresponding population during lymphocyte development. One of the most dramatic microenvironmental shifts during T-cell development occurs in association with T-cell maturation in the thymus, with the movement of a number of positively selected mature phenotype cells to the medulla and the eventual emigration and trafficking to secondary lymphoid tissues.9 Export of mature T cells is inhibited in pertussis toxin (PTX) transgenic mice, which appears to be consistent with the involvement of G-protein-linked chemoattractant receptors in this migratory event.10,11 Recently, it has been reported that the developmentally determined movement is associated with changes in the responsiveness of defined immature and mature thymic subsets to chemokines expressed in the thymus.12 Thymus-expressed chemokine (TECK) predominantly attracts cortical thymocytes, whereas macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC), secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine (SLC) and macrophage inflammatory protein-3β (MIP-3β) attract medullary thymocytes. Thus, these chemokines appear to contribute to the distribution of immature and mature thymocytes to the relevant microenvironment.

Stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) is a widely expressed chemokine to which most mononuclear leucocytes respond.13,14 The SDF-1α is abundantly expressed in the thymus. Recently, it was reported that CXCR4, a chemokine receptor for SDF-1α, was expressed highly on cortical thymocytes and poorly on medullary thymocytes in mice.15,16 However, no appreciable difference has been reported in the migratory responsiveness to SDF-1α between cortical and medullary thymocytes.12 This discrepancy between the CXCR4 expression and the responsiveness to SDF-1α has not been explained. Thus, a potential role of SDF-1α in targeted migratory events during thymic development is still under consideration.

Extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules, such as fibronectin, laminin and collagen, represent important components of the thymic microenvironment.17,18 These proteins are secreted by endothelial and epithelial cells, associated with basement membranes, and are thought to support the growth and development of thymocytes and epithelial cells.19,20 The binding of haematopoietic cells to the fibronectin and laminin is mediated by integrin receptors.21–29 The classical receptor of fibronectin is α5β1 (very late antigen-5, VLA-5) that recognizes the minimum binding sequence Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD), and another well characterized receptor is α4β1 (VLA-4) that binds sites within the alternatively spliced IIICS region of the molecule defined by the synthetic peptides CS1 and CS5.21–27 On the other hand, laminin binds α1β1 (VLA-1), α2β1 (VLA-2), α3β1 (VLA-3), α6β1 (VLA-6), α7β1 (VLA-7) and α6β4.28,29 Although fibronectin and laminin are major components of ECM in the thymus,17,18 the physiological role of these proteins in the thymus has not been fully explained. In the present study, we examined the effects of ECM on the responsiveness of cortical and medullary thymocytes to chemokines. We demonstrate herein that chemotactic activity of SDF-1α to CD4/8 double-positive (DP) thymocytes, but not to CD4 or CD8 single-positive (SP) cells, is considerably and selectively enhanced in the presence of fibronectin or laminin.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6) female mice were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan). All mice were used at 6–9 weeks of age. All experiments were approved by the regulations of Hokkaido University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant murine SDF-1α and MDC were purchased from PeproTech (London, UK). Recombinant murine MIP-3β was purchased from Genzyme (Cambridge, MA). Purified murine fibronectin and murine laminin were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA) and Life Technologies (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. Purified murine collagen type IV and PTX were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO). Biotinylated anti-mouse CD69 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (clone H1.2F3),30 phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse CD8 mAb (clone Ly-2),31 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 mAb (clone RM4-5),32 and streptavidin-Cy-Chrome™ were obtained from PharMingen (La Jolla, CA). Purified anti-mouse CD104 mAb (clone 346-11A),33 anti-mouse CD29 mAb (clone HMβ1-1)34 and rat immunoglobulin G2b (IgG2b; clone A95-1) as a control immunoglobulin were obtained from PharMingen.

Chemotaxis assays

Chemotaxis assays were conducted as described.12,13 Thymi were removed from C57BL/6 mice and single cell suspensions were prepared by passing through a stainless steel mesh. In brief, 1 × 106 thymocytes were added to upper wells of 5-µm pore, polycarbonate 24-well tissue culture inserts (Costar, Cambridge, MA) in 100 µl, with 600 µl of chemokine or medium in the bottom wells. All migration assays were conducted in RPMI-1640 with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37° in 5% CO2 for 90 min. In the case of ECM coating, murine fibronectin, laminin, or collagen type IV in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to upper wells, and was incubated over night at 4°. Then the wells were washed with PBS and used for chemotaxis assay. The ECM were used at 50 µg/ml, since maximal effects of fibronectin and laminin on chemotactic performances were observed at 10–100 µg/ml (data not shown). To determine the effect of PTX on chemotaxis, the cells were pretreated with 0·1–10 ng/ml of PTX in RPMI-1640 with 1% BSA at 37° for 60 min, and then 100 µl of the cells (1 × 106 cells) were added to the upper well. To inhibit interaction of integrins containing β1 or β4 chain to the ligands, the cells (1 × 107 cells/ml) were incubated with 20 µg/ml of anti-mouse CD104 (β1 chain) mAb (346-11A), anti-mouse CD29 (β1 chain) mAb (HMβ1-1), or rat IgG2b (A95-1) in RPMI-1640 with 1% BSA at 0° for 60 min, and then 100 µl of the cells (1 × 106 cells) were added to the upper well. Concentrations of recombinant murine SDF-1α, MDC and MIP-3β for the optimal chemotaxis were determined (data not shown), and all chemokines were used at 400 ng/ml. A 100-µl aliquot of migrated cells recovered from each lower well was counted using comparison to a known number of beads as an internal standard as described.13,35 The remainders of the cells were stained with fluorescence-labelled mAbs (see below). The number of cells in the starting population and the migrated population was calculated for each subpopulation, and the per cent migration was determined from these values.

Flow cytometry

The migrated cells and starting populations were stained for two- or three-colour flow cytometry with biotinylated anti-mouse CD69 mAb (H1.2F3), PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD8 mAb (Ly-2), FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 mAb (RM4-5), and streptavidin-Cy-Chrome™. Flow cytometry was performed on EPICS® XL (Coulter Co. Miami, FL).

Statistical analysis

The Student's t-test was used to analyse data for significant differences. P-values less than 0·05 were regarded as significant.

Results

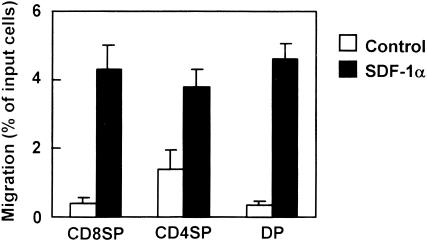

Chemotactic preferences of SDF-1α for thymocyte subsets

We first analysed the chemotactic activity of SDF-1α for CD4/8 DP, CD4 SP and CD8 SP subsets in the murine thymus. B6 thymocytes were added to upper wells of 24-well tissue culture inserts with the presence or absence of SDF-1α in the bottom wells. As shown in Fig. 1, migrations of CD4 SP, CD8 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes were significantly increased by SDF-1α (P < 0·05 versus control). SDF-1α induced the same levels of migration among cortical (CD4/8 DP) and medullary (CD4 and CD8 SP) populations in proportion to the original number of input cells in the upper well. This finding is consistent with a previous report of Campbell et al.12 that no appreciable differences in the SDF-1α responsiveness were detected between cortical and medullary thymocytes.

Figure 1.

Chemotactic preferences of SDF-1α for thymocyte subsets. Numbers of CD8 SP, CD4 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes migrating to the lower well are expressed as the percentage of input thymocytes in the upper well at the start time of chemotaxis assay. Each column represents the mean±SD of four independent experiments.

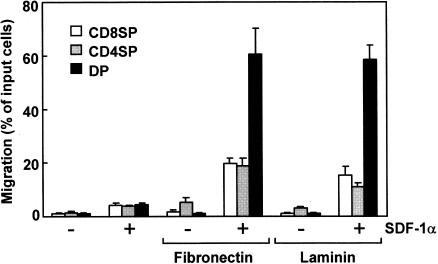

Enhanced chemotactic activities of SDF-1α for thymocytes by ECM

Fibronectin and laminin are major ECM in the thymus. To determine the effects of these proteins on SDF-1α-induced migration, the upper wells of culture inserts were coated with fibronectin or laminin before chemotaxis assays (Fig. 2). The fibronectin- or laminin-coating alone showed no notable influence on the constitutive migrations of CD8 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes, and resulted in a slight enhancement of that of CD4 SP thymocytes. On the other hand, the chemotactic activity of SDF-1α for CD4/8 DP thymocytes was considerably enhanced (more than 10-fold) in the presence of laminin or fibronectin. Although SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis of CD4 and CD8 SP thymocytes was also enhanced by fibronectin- or laminin-coating, the enhancement was not as impressive as that of CD4/8 DP thymocytes. Thus, fibronectin and laminin appeared to enhance selectively the SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis of CD4/CD8 DP thymocytes. Chemotactic activities of SDF-1α for both SP and DP thymocytes were unaffected by coating upper wells with type IV collagen, another component of the thymic microenvironment (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Chemotactic preferences of SDF-1α for thymocytes in the presence of laminin and fibronectin. Numbers of CD8 SP, CD4 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes migrating to the lower well are expressed as the percentage of input thymocytes in the upper well at the start time of chemotaxis assay. The upper wells were coated with fibronectin or laminin. Each column represents the mean±SD of four independent experiments.

The enhanced migration of CD4/8 DP thymocytes by laminin was almost at the same level as that by fibronectin (Fig. 2). In contrast, the enhanced migration level of CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes by laminin was lower than that by fibronectin. Thus, it seems that laminin is a more selective attractant than fibronectin for CD4/CD8 DP thymocytes.

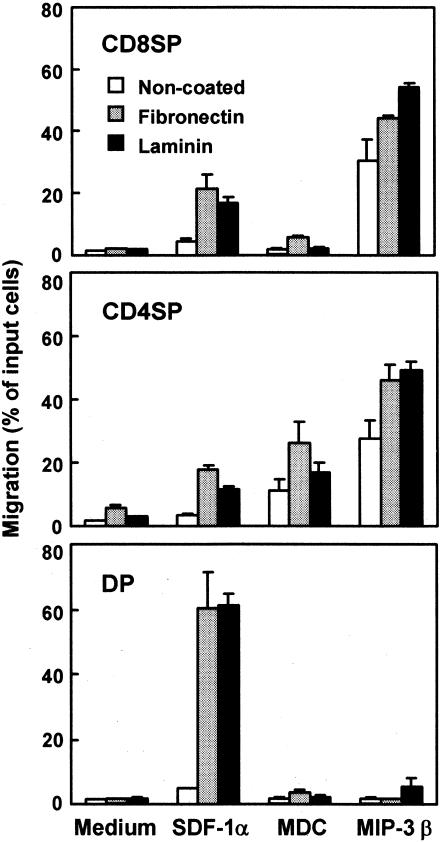

Effects of fibronectin or laminin on chemotactic activities of SDF-1α, MDC and MIP-3β for thymocytes

MDC and MIP-3β are expressed in the thymus and thought to contribute to the distribution of medullary thymocytes.12 Figure 3 shows the effects of laminin and fibronectin on the chemotactic activity of MDC or MIP-3β for thymocyte subpopulations and compares these effects with that of SDF-1α. In the absence of ECM, CD8 SP thymocytes showed only a slight response to MDC but marked migration to MIP-3β. CD4 SP thymocytes were significantly attracted to both MDC and MIP-3β, as compared to SDF-1α. CD4/8 DP thymocytes showed no significant migration to MDC or MIP-3β in the absence of EMC.

Figure 3.

Effects of laminin and fibronectin on chemotactic preferences of SDF-1α, MDC and MIP-3β for thymocytes. Numbers of CD8 SP, CD4 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes migrating to the lower well are expressed as the percentage of input thymocytes in the upper well at the start time of chemotaxis assay. The upper wells were coated with fibronectin or laminin. Each column represents the mean±SD of three independent experiments.

In the presence of fibronectin, chemotactic activities of MDC for CD8 and CD4 SP thymocytes were enhanced, whereas CD4/8 DP thymocytes showed only negligible migration to MDC (Fig. 3). Laminin showed no significant enhancement of chemotactic activities of CD8 SP, CD4 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes to MDC. MIP-3β-induced chemotaxis of CD8 SP and CD4 SP thymocytes was slightly enhanced by fibronectin and laminin. MIP-3β with laminin but not with fibronectin induced slight migration of CD4/8 DP thymocytes. It should be noted that again SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis of CD4/8 DP thymocytes was markedly enhanced by either fibronectin or laminin.

The enhancements of chemotactic activity of MDC and MIP-3β by fibronectin or laminin were not so remarkable for all three populations examined as compared with the enhancement of SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis of CD4/8 DP thymocytes by these ECM. Thus, fibronectin and laminin appear to enhance selectively the chemotactic activity of SDF-1α for CD4/8 DP thymocytes.

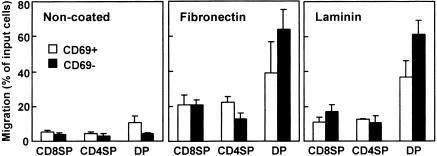

Enhanced chemotactic activities of SDF-1α by laminin or fibronectin for CD69 positive and negative subsets in thymocytes

To examine further the developmental stage of thymocytes that respond to SDF-1α with fibronectin or laminin, migratory responses were analysed for well-established phenotypically defined stages, CD69− CD4/8 DP (before positive selection), CD69+ CD4/8 DP (post-positive selection or transitional between cortex and medulla), CD69+ SP, and CD69− SP.36–38 Figure 4 compares the enhanced activities of SDF-1α with laminin or fibronectin for CD69+ and CD69− subsets among CD8 SP, CD4 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes. In the absence of ECM, no differences in the responsiveness to SDF-1α were detected between CD69+ and CD69− cells among CD8 SP or CD4 SP thymocytes. By contrast, CD69+ DP thymocytes showed significantly greater chemotaxis to SDF-1α than CD69− DP thymocytes (P < 0·05).

Figure 4.

Chemotactic preferences of SDF-1α with laminin and fibronectin for CD69 positive and negative subsets in CD8 SP, CD4 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes. Numbers of CD8 SP, CD4 SP and CD4/8 DP thymocytes migrating to the lower well are expressed as the percentage of input thymocytes in the upper well at the start time of chemotaxis assay. The upper wells were coated with fibronectin or laminin. Each column represents the mean±SD of four independent experiments.

CD69+ CD4 SP cells responded more prominently to SDF-1α with fibronectin than CD69− CD4 SP cells (P < 0·05). CD69+ CD8 SP and CD69− CD8 SP cells showed the same levels of migration to SDF-1α with fibronectin. In the CD4/8 DP population, CD69− cells showed higher responsiveness to SDF-1α with fibronectin than CD69+ cells (P < 0·05). No notable differences in the responsiveness to SDF-1α with laminin were detected between CD69+ and CD69− cells among CD8 SP or CD4 SP thymocytes. By contrast, again CD69− CD4/8 DP thymocytes responded more vigorously to SDF-1α with laminin than CD69+ DP thymocytes (P < 0·01).

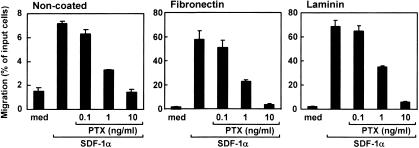

Effects of PTX on enhanced chemotactic activities of SDF-1α by laminin or fibronectin for CD4/8 DP thymocytes

PTX inhibits Gi/Go-proteins specifically among other G-proteins such as Gq, Gs, or G12/G13 proteins,39 which results in inhibition of cell migrations induced by chemokines.40,41 It has been reported that SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis is more sensitive to PTX than that induced by other chemokines.42 Figure 5 shows the effect of PTX on the chemotactic activity of SDF-1α with laminin or fibronectin for CD4/8 DP thymocytes. PTX partially inhibited SDF-1α-dependent chemotaxis at 1 ng/ml and almost completely at 10 ng/ml without ECM. Enhanced chemotactic activities of SDF-1α by fibronectin or laminin were also reduced by PTX in the same dose-dependent manner as the SDF-1α-dependent chemotaxis without ECM. Thus, the sensitivity of SDF-1α-dependent migration to PTX was unaffected in the presence of fibronectin or laminin.

Figure 5.

Chemotactic preferences of SDF-1α with laminin and fibronectin for CD4/8 DP thymocytes pretreated with PTX. Thymocytes were preincubated with PTX at the indicated concentrations for 1 hr. Numbers of CD4/8 DP thymocytes migrating to the lower well are expressed as the percentage of input thymocytes in the upper well at the start time of chemotaxis assay. The upper wells were coated with fibronectin or laminin. Each column represents the mean±SD of triplicate wells. The analysis was repeated twice with essentially the same results.

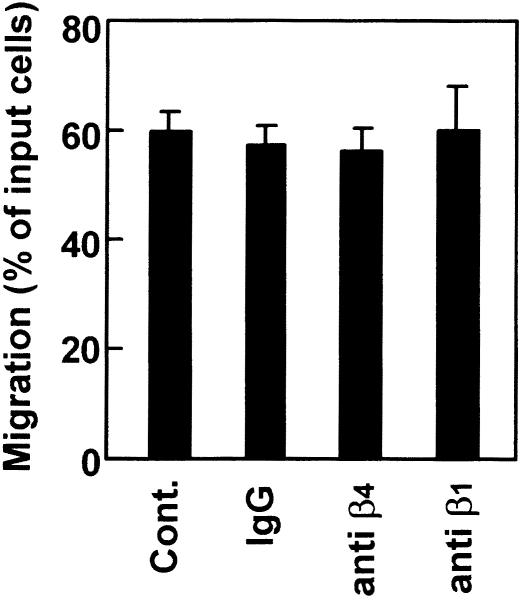

Effects of mAb against β1 and β4 integrins on the enhanced chemotactic activity of SDF-1α for CD4/8 DP thymocytes in the presence of laminin

It has been demonstrated that fibronectin receptors are α4β1 (VLA-4) and α5β1 (VLA-5), whereas laminin receptors are α1β1 (VLA-1), α2β1 (VLA-2), α3β1 (VLA-3), α6β1 (VLA-6), α7β1 (VLA-7) and α6β4.21–29 Thus, it seemed that these receptors were involved in the enhancement of SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis by ECM. It has been reported that an anti-β1 mAb, HMβ1-1 (10 µg/ml), inhibits cell adhesion and intracellular signalling mediated by interaction of β1-chain-containing integrins and ECM.34 To examine whether these integrins are involved in the enhancement of SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis by ECM, thymocytes were treated with HMβ1-1 before chemotaxis assay. As shown in Fig. 6, HMβ1-1 at 20 µg/ml exerted no influence on the enhancement of chemotactic activity of SDF-1α by laminin for CD4/8 DP thymocytes. This finding suggests that β1 integrins are not involved in the enhancement of SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis. An anti-β4 mAb, 346-11A, at 20 µg/ml also showed no effect on the enhanced chemotactic activity of SDF-1α with laminin. Although the biological function of 346-11A has not been fully elucidated, it seems to us that β4 integrin may not be involved in the enhancement of chemotaxis. Only 3–6% of murine thymocytes express β4 integrin.43

Figure 6.

Chemotactic preferences of SDF-1α by laminin and fibronectin for CD4/8 DP thymocytes pretreated with mAbs against β1 and β4 integrins. Thymocytes were preincubated with mAbs (20 µg/ml) against β1 and β4 integrins for 1 hr. Numbers of CD4/8 DP thymocytes migrating to the lower well are expressed as the percentage of input thymocytes in the upper well at the start time of chemotaxis assay. The upper wells were coated with fibronectin or laminin. Each column represents the mean±SD of triplicate wells. The analysis was repeated twice with essentially the same results.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that the chemotactic performance of SDF-1α for cortical thymocytes was considerably enhanced by fibronectin or laminin, which are major components of the thymic microenvironment (Fig. 2). Although this enhancement by ECM was also observed in medullary thymocytes, the degree was not so impressive as compared with that in cortical thymocytes. On the other hand, the chemotactic activities of MDC and MIP-3β for both cortical and medullary thymocytes were only slightly enhanced by fibronectin or laminin compared with those of SDF-1α (Fig. 3). Thus, fibronectin and laminin appear to enhance selectively the chemotactic activity of SDF-1α for CD4/8 DP thymocytes. Thus far, no report has shown this phenomenon. It was reported that a significant level of SDF-1α mRNA was expressed in the cortex and the subcapsular region in the thymus.15 It seems to us that SDF-1α in the presence of the ECM contributes to distribution of CD4/8 DP thymocytes in the thymic cortex. The location of ECM molecules has been immunohistochemically analysed in the murine thymus.17,44 Although both fibronectin and laminin are expressed in the cortex and medulla, these molecules are more abundant in the medulla.17,44 On the other hand, a significant level of SDF-1α mRNA is expressed in the cortex but not in the medulla of the thymus.15 Thus, it seems to us that the distribution of CD4/8 DP thymocytes in the cortex is largely determined by the level of SDF-1α. The abundant presence of ECMs in the medulla may enhance the migration of CD4/8 DP thymocytes to the cortex expressing SDF-1α.

Recently, expression of CXCR4, a chemokine receptor for SDF-1α, was demonstrated on murine thymocytes using a mAb, 2B11. This mAb was raised against human CXCR4 and specifically binds to human and murine CXCR4.16 Almost all CD4/8 DP thymocytes express a large amount of CXCR4. On the other hand, CXCR4 is only slightly expressed on CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes. However, only a small proportion of CD4/8 DP thymocytes (less than 5% of input cells) responded to SDF-1α in the absence of ECM, and this responsiveness was at the same level as those of CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes (Fig. 1).12 In contrast, in the presence of laminin or fibronectin, SDF-1α strongly attracted CD4/8 DP thymocytes and the migration of DP thymocytes was considerably greater than those of CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes (Fig. 2). These observations suggest that the responsiveness of CD4/8 DP thymocytes to SDF-1α is vastly dependent on the presence of the ECM. It seems that in the absence of the ECM, CD4/8 DP thymocytes bearing a high concentration of CXCR4 cannot fully respond to SDF-1α and no appreciable difference in the migratory responsiveness to SDF-1α alone between cortical and medullary thymocytes has thereby been reported.12

The specificity and affinity of T-cell receptors (TCR) on DP thymocytes to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) expressed in the thymus determine the fate of T-cell development.45 The negative selection process eliminates potentially harmful CD4/8 DP thymocytes that are reactive with MHC plus self-antigens, whereas positive selection saves CD4/8 DP thymocytes with TCR that recognize self-MHC plus foreign antigens. In the present study, we examined whether the enhanced chemotactic activity of SDF-1α with ECM was associated with the thymic development and the selection process. Since expression of CD69 is induced on CD4/8 DP thymocytes after initiation of the selection, and the CD69 expression on SP thymocytes decreases before their emigration from the thymus,36–38 we compared the SDF-1α-induced chemotactic activity between CD69 positive and negative subsets in the presence of laminin or fibronectin. We found that in the absence of ECM, a larger number of CD69+ DP thymocytes responded to SDF-1α than of CD69− DP cells (Fig. 4). This finding appears to be consistent with a previous report by Kim et al.42 These authors showed that SDF-1α attracted CD69+ cells more prominently than CD69− cells in DP thymocytes, and suggested that this phenomenon might be related to the rescue of selected thymocytes from phagocytic macrophages. On the other hand, using a SDF-1–immunoglobulin fusion protein, Suzuki et al.46 demonstrated that the expression of SDF-1α receptor is down-regulated after positive selection of DP thymocytes. Thus, chemotactic activity of SDF-1α may not necessarily be related to the expression level of SDF-1α receptor in the absence of ECMs.

In the present study, SDF-1α with laminin or fibronectin induced more prominent chemotaxis in CD69− cells than in CD69+ cells among DP thymocytes (Fig. 4). Thus, it seems that DP thymocytes lose their reactivity to SDF-1α with fibronectin or laminin after the selection step, and these are ready to move toward the medulla. It seems that the low reactivity of CD69+ DP thymocytes to SDF-1α is attributed to the decreased expression of SDF-1α receptor.46 In addition, expression levels of fibronectin and laminin receptors might also be involved in the reactivity to SDF-1α. As we reported in the present study (Fig. 6), unknown receptors for fibronectin and laminin appeared to be involved in the enhancement of responsiveness to SDF-1α. It should be pursued in future studies whether the expression level of these unknown receptors for fibronectin and laminin is different between CD69+ and CD69− DP thymocytes. In CD4 SP thymocytes, SDF-1α with fibronectin but not with laminin was more attractive to CD69+ cells than CD69− cells (Fig. 4). This reduction in the reactivity to SDF-1α may be related to the export of CD69− CD4 SP cells from the thymus.

PTX specifically inhibits Gi/Go proteins but not other G-proteins such as Gq, Gs, or G12/G13 proteins.39 Chemokine receptors are coupled with Gi proteins, and PTX inhibits cell migrations induced by chemokines.39–41 Sensitivity to PTX is different among chemokine receptor molecules,42 implicating that each chemokine receptor uses different Gi-proteins for signalling. SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis is highly sensitive to PTX compared with those induced by the other chemokines.42 Indeed, SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis, either with or without ECM, was almost completely inhibited by PTX at 10 ng/ml (Fig. 5). Thus, fibronectin and laminin may enhance signalling mediated by Gi-protein coupled with SDF-1α receptor.

Binding of haematopoietic cells to fibronectin and laminin is mediated by a number of integrins. Receptors on these haematopoietic cells for fibronectin are α4β1 and α5β1, whereas those for laminin are α1β1, α2β1, α3β1, α6β1, α7β1 and α6β4.28,29 We examined whether these receptors were involved in the enhanced chemotactic activity of SDF-1α with ECM using specific mAb against β1 and β4. The enhanced chemotactic activity of SDF-1α with laminin was unaffected by the anti-β1 mAb, HMβ1-1, and the anti-β4 mAb, 346-11A (Fig. 6). It has been demonstrated that HMβ1-1 inhibits cell adhesion and an intracellular signalling mediated by interaction of β1-coupled integrins and ECM. β4 integrin is expressed at high levels on fetal thymocytes and at very low levels on adult thymocytes in mice.43 The proportion of β4-positive thymocytes is only 3–6% in adult mice.43 Thus, β1- or β4-coupled integrins are unlikely to be involved in the enhancement of SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis. In addition to β1 and β4 integrins, CD44 also binds to fibronectin and laminin via a heparin-binding domain.47 However, hyaluronic acid, a CD44 ligand and collagen type IV that has a heparin-binding domain47 showed no enhancement of SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis (data not shown). In addition, soluble fibronectin or laminin also markedly enhanced the responsiveness of CD4/CD8 DP thymocytes to SDF-1α (data not shown). From these observations, we consider that unknown receptor(s) may be involved in the enhancement of SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis by ECM.

In conclusion, our present study indicates that fibronectin and laminin are important ECM that augment the chemotactic activity of SDF-1α in the thymus. The remarkable enhancement of chemotaxis by ECM was demonstrated only for CD4/8 DP thymocytes. The combination of SDF-1α and ECM appears to be involved in the developmental transition of thymocytes and contributes to the distribution in the thymus.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ms Kaori Kohno for her secretarial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B.C.) by the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Research Grant for Immunology, Allergy and Organ Transplant, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan. This study was also supported by grants from the Hokkaido Foundation for the Promotion of Scientific and Industrial Technology, The Tomakomai East Hospital Foundation and The Nishimura Aging Fund.

Abbreviations

- DP

double positive

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MDC

macrophage-derived chemokine

- MIP-3β

macrophage inflammatory protein-3β

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- SDF-1α

stromal cell-derived factor-1α

- SLC

secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine

- SP

single positive

- VLA

very late antigen

References

- 1.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, MoSeries B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines-CXC and CC chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, MoSeries B. Human chemokines: an update. Ann Rev Immunol. 1997;15:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rollins BJ. Chemokines. Blood. 1997;90:909–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schall TJ, Bacon KB. Chemokines, leukocyte trafficking, and inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:865–73. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedrick JA, Zlotnik A. Chemokines and lymphocyte biology. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:343–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy PM. The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:593–633. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy PM. Chemokine receptors: Structure, function and role in microbial pathogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7:47–64. doi: 10.1016/1359-6101(96)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bokoch GM. Chemoattractant signaling and leukocyte activation. Blood. 1995;86:1649–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson G, Moore NC, Owen JJ, Jenkinson EJ. Cellular interactions in thymocyte development. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;7:73–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaffin KE, Perlmutter RM. A pertussis toxin-sensitive process controls thymocyte emigration. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2565–73. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaffin KE, Beals CR, Wilkie TM, Forbush KA, Simon M, Perlmutter RM. Dissection of thymocyte signaling pathways by in vivo expression of pertussis toxin ADP-ribosyltransferase. EMBO J. 1990;9:3821–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell JJ, Pan J, Butcher EC. Related developmental switches in chemokine responses during T cell maturation. J Immunol. 1999;163:2353–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell JJ, Bowman EP, Murphy K, et al. 6-C-kine (SLC), a lymphocyte adhesion-triggering chemokine expressed by high endothelium, is an agonist for the MIP-3β receptor CCR7. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1053–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleul CC, Fuhlbrigge RC, Casanovas JM, Aiuti A, Springer TA. A highly efficacious lymphocyte chemoattractant, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) J Exp Med. 1996;184:1101–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki G, Sawa H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Pertussis toxin-sensitive signal controls the trafficking of thymocytes across the corticomedullary junction in the thymus. J Immunol. 1999;162:5981–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schabath R, Muller G, Schubel A, Kremmer E, Lipp M, Forster R. The murine chemokine receptor CXCR4 is tightly regulated during T cell development and activation. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:996–1004. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.6.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lannes-Vieira J, Dardenne M, Savino W. Extracellular matrix components of the mouse thymus microenvironment: ontogenetic studies and modulation by glucocorticoid hormones. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39:1539–46. doi: 10.1177/39.11.1918928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyd RL, Tucek CL, Godfrey DI, et al. The thymic microenvironment. Immunol Today. 1993;14:445–59. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90248-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yurchenco PD, O'Rear JJ. Basal lamina assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:674–81. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burgeson RE, Christiano AM. The dermal-epidermal junction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:651–8. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierschbacher MD, Ruoslahti E. Cell attachment activity of fibronectin can be duplicated by small synthetic fragments of the molecule. Nature. 1984;309:30–3. doi: 10.1038/309030a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aota S, Nomizu M, Yamada KM. The short amino acid sequence Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn in human fibronectin enhances cell-adhesive function. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24756–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danen EHJ, Aota S, van Kraats AA, Yamada KM, Ruiter DJ, van Muijen GNP. Requirement for the synergy site for cell adhesion to fibronectin depends on the activation state of integrin alpha 5 beta 1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21612–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leahy DJ, Aukhil I, Erickson HP. 2.0 A crystal structure of a four-domain segment of human fibronectin encompassing the RGD loop and synergy region. Cell. 1996;84:155–64. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphries MJ, Komoriya A, Akiyama SK, Olden K, Yamada KM. Identification of two distinct regions of the type III connecting segment of human plasma fibronectin that promote cell type-specific adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:6886–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohri H, Katoh K, Iwamatsu A, Okubo T. The novel recognition site in the C-terminal heparin-binding domain of fibronectin by integrin alpha 4 beta 1 receptor on HL-60 cells. Exp Cell Res. 1996;222:326–32. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0042. 10.1006/excr.1996.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mould AP, Komoriya A, Yamada KM, Humphries MJ. The CS5 peptide is a second site in the IIICS region of fibronectin recognized by the integrin alpha 4 beta 1. Inhibition of alpha 4 beta 1 function by RGD peptide homologues. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3579–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diamond MS, Springer TA. The dynamic regulation of integrin adhesiveness. Curr Biol. 1994;4:506–17. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokoyama WM, Koning F, Kehn PJ, Pereira GM, Stingl G, Coligan JE, Shevach EM. Characterization of a cell surface-expressed disulfide-linked dimer involved in murine T cell activation. J Immunol. 1988;141:369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiku H, Kisielow P, Bean MA, Takahashi T, Boyse EA, Oettgen HF, Old LJ. Expression of T-cell differentiation antigens on effector cells in cell-mediated cytotoxicity in vitro. Evidence for functional heterogeneity related to the surface phenotype of T cells. J Exp Med. 1975;141:227–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bierer BE, Sleckman BP, Ratnofsky SE, Burakoff SJ. The biologic roles of CD2, CD4, and CD8 in T-cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:579–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennel SJ, Foote LJ, Flynn KM. Related tumor antigen on benign adenomas and on murine lung carcinomas quantitated by a two-site monoclonal antibody assay. Cancer Res. 1986;46:707–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noto K, Kato K, Okumura K, Yagita H. Identification and functional characterization of mouse CD29 with a mAb. Int Immunol. 1995;7:835–42. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell JJ, Qin S, Bacon KB, Mackay CR, Butcher EC. The biology of chemokine and classical chemoattractant receptors: differential requirements for adhesion-triggering versus chemotactic responses in lymphoid cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:255–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamashita I, Nagata T, Tada T, Nakayama T. CD69 cell surface expression identifies developing thymocytes which audition for T cell antigen receptor-mediated positive selection. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1139–50. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.9.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandle D, Muller S, Muller C, Hengartner H, Pircher H. Regulation of RAG-1 and CD69 expression in the thymus during positive and negative selection. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:145–51. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabor MJ, Godfrey DI, Scollay R. Recent thymic emigrants are distinct from most medullary thymocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2010–15. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Post GR, Brown JH. G protein-coupled receptors and signaling pathways regulating growth responses. FASEB J. 1996;10:741–9. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.7.8635691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spangrude GJ, Sacchi F, Hill HR, van Epps DE, Daynes RA. Inhibition of lymphocyte and neutrophil chemotaxis by pertussis toxin. J Immunol. 1985;135:4135–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cyster JG, Goodnow CC. Pertussis toxin inhibits migration of B and T lymphocytes into splenic white pulp cords. J Exp Med. 1995;182:581–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim CH, Pelus LM, White JR, Broxmeyer HE. Differential chemotactic behavior of developing T cells in response to thymic chemokines. Blood. 1998;91:4434–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wadsworth S, Halvorson MJ, Coligan JE. Developmentally regulated expression of the beta 4 integrin on immature mouse thymocytes. J Immunol. 1992;149:421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savino W, Villa-Verde DMS, Lannes-Vieira J. Extracellular matrix proteins in intrathymic T-cell migration and differentiation? Immunol Today. 1993;14:158–60. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90278-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robey E, Fowlkes BJ. Selective events in T cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suzuki G, Nakata Y, Dan Y, Uzawa A, Nakagawa Y, Saito T, Mita K, Shirasawa T. Loss of SDF-1 receptor expression during positive selection in the thymus. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1049–56. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.8.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lesley J, Hyman R, Kincade PW. CD44 and its interaction with extracellular matrix. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:271–335. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]