Abstract

The majority of the human tumour-associated antigens characterized to date are derived from non–mutated self-proteins. However, nothing is known about the development of autoreactive and tumour-associated antigen-recognizing T cells. Tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-2 is a non-mutated melanocyte differentiation antigen and TRP-2-recognizing CD8+ T cells are known to show responses to melanoma both in humans and mice. In addition, TRP-2-reactive T cells with low avidity have been suggested to be readily induced from the spleen cells of naïve mice. On the other hand, recent reports suggest that self antigen-reactive CD8+ T cells can be positively selected in the periphery. In this study, we tested the possibility that TRP-2-reactive CD8+ T cells in naïve mice could develop via the extrathymic pathway. As a consequence, TRP-2-reactive CD8+ T cell precursors in naïve C57BL/6 mice were suggested to express both interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor β chain (IL-2Rβ) and CD44 molecules, in a manner similar to that of extrathymically developed T cells. Furthermore, IL-2Rβ+ CD44+ CD8+ T cells were detected in the adult thymectomized and bone marrow-reconstituted mice, and functional TRP-2-reactive T cells were generated from their spleen cells. Overall, these results suggest that low avidity CD8+ T cells recognizing TRP-2 can be developed extrathymically.

Introduction

Recent advances in tumour immunology have revealed that self-antigens on human cancer are the most prevalent antigens recognized by the immune system.1–7 Among them, tyrosine-related protein (TRP)-2 is a non-mutated melanocyte differentiation antigen (MDA) recognized by melanoma-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) both in humans and mice.8–10 In C57BL/6 mice, CTL reactive with the murine B16 melanoma were found to recognize TRP-2180-188 peptide in the context of H-2Kb.8,11 In addition, TRP-2180-188-reactive T cells with low avidity can be readily induced from the spleen cells of naïve mice when cultured with a high dose of the TRP-2180-188 peptide,12 thus suggesting the presence of a considerable number of TRP-2180-188-recognizing T-cell precursors with low avidity in naïve mice.

Most peripheral T cells require the thymus for their development. The repertoire of antigen specificities of T cells is shaped by the processes of positive and negative selection.13 Positive selection educates T cells that are capable of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted recognition of antigens and negative selection eliminates those T cells that are potentially autoreactive. In addressing why TRP-2-recognizing and autoreactive T-cell precursors can exist in the periphery of naïve mice at a relatively high level, two possibilities can be proposed. First, TRP-2-reactive T cells were positively selected in the thymus, thereafter escaped negative selection and consequently appeared in the periphery. Because there is no expression of MDA in the thymus, their specificity could be a result of cross-reactivity between TRP-2-derived peptide–MHC and self other peptide–MHC. Second, TRP-2-reactive T cells developed via the extrathymic pathway. It is known that some peripheral T cells do not require the thymus for their development.14 These extrathymically developed T cells are abundant in the gut and liver.15,16 In addition, it was recently reported that, by using H-Y antigen-specific T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice, self antigen-specific CD8+ T cells can be positively selected in the absence of the thymus.17

In this study, we examined the possibility that the prevalent presence of TRP-2-recognizing CD8+ T cell precursors in naïve mice could result from their extrathymic development. Our results indicate that CD8+ precursors of TRP-2180-188-recognizing T cells in naïve C57BL/6 mouse express IL-2Rβ chain (CD122) and CD44, both of which are known to be expressed on extrathymically developed T cells.15,17 Such T cells were detected in the adult thymectomized and bone marrow-reconstituted (ATX-BM) mice. Furthermore, functional TRP-2180-188-reactive T cells were generated from the spleen cells of the ATX-BM mice. Taken together, these results suggest that low avidity CD8+ T cells, which recognize TRP-2, can thus be developed extrathymically.

Materials and methods

Mice and tumour lines

Female Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 (B6: H-2b) mice were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka Japan). Female Thy1.1+ C57BL/10 (B10: H-2b) mice were kept in a specific pathogen-free animal facility in our institution. Both mice were used for experiments at from 8 to 12 weeks of age. B16 and EL4 are melanoma and T cell lymphoma, respectively. Their origins are all from B6 mice (H-2b). B16L is an MHC class I loss variant of B16 melanoma and B16L-Kb is a subline of B16L transfected with H-2Kb gene.11 All tumour cell lines were maintained in vitro in a complete medium. RPMI-1640 (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal claf serum (FCS; HyClone, Logan, UT), 5 × 10−5 m 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), 20 mm HEPES, 30 µg/ml gentamicin (Schering, Kenilworth, NJ), and 0·2% sodium bicarbonate was used as the complete medium.

Peptides

Both murine TRP-2180-188 (SVYDFFVWL)8 and gp10025-33 (EGSRNQDWL) peptides18 were purchases from the Asahi Technoglass Co. (Chiba, Japan) and diluted by dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) at a dose of 10 mg/ml. Purity (> 95%) was confirmed by reverse phased high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). To pulse the peptides on stimulator cells, the cells were incubated with the peptides for 90 min at 37°. Thereafter, these peptide-pulsed cells were washed twice with complete medium.

Generation of TRP-2180-188-recognizing T cells with low or high avidity

To generate TRP-2180-188-recognizing T cells with low avidity, spleen cells (5 × 106/well) from naïve B6 mice were cultured with the TRP-2180-188 peptide at a dose of 5 µm in 24-well plates. On day 3, IL-2 was added at a final concentration of 10 U/ml. On day 7, the viable cells were enriched using Lympholyte-M (Cedarlane Laboratories, Ontario, Canada) and then re-cultured at a dose of 5 × 105/well with 25 Gy-irradiated B6 spleen cells (5 × 106/well), which were pulsed with 5 µm TRP-2180-188 peptide. On day 10, the half medium was changed with the complete medium containing 20 U/ml IL-2. Six days after the fourth stimulation, the viable cells were enriched using Lympholyte-M and then were used for the experiments. To generate TRP-2180-188-recognizing T cells with high avidity, spleen cells from B6 mice, which were subcutaneously immunized twice with 2 × 106 inactivated granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing B16 melanoma cells, were used. To prepare inactivated cells for immunization, the GM-CSF-producing B16 melanoma cells were cultured with 100 µg/ml mitomycin C (Kyowa Hakko Kogyo, Tokyo) for 90 min. The spleen cells from the immunized mice were cultured with the same protocol except a different dose of the TRP-2180-188 peptide dose, 10 nm. Purified human rIL-2 was obtained from Takeda (Osaka, Japan) and the unit of IL-2 was expressed in international units.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

To examine the interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production, the cultured cells were incubated with several stimulator cells. EL4 cells were pulsed with the indicated doses of the peptides. After 24 hr culture, the level of IFN-γ in the supernatant was measured by ELISA using mouse IFN-γ DuoSeT (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA).

In vitro proliferation assay

Whole spleen cells (5 × 105/well) were cultured with the indicated peptides in 96-well flat plates. In some experiments, nylon wool (NW) non-adherent or NW non-adherent and CD44+ cell-depleted spleen cells (5 × 104/well) from naïve B6 mice were cultured with 25 Gy-irradiated B6 spleen cells (5 × 105/well) in the presence of the peptides at a dose of 5 µm. In both experiments, on day 3, IL-2 was added to each well at a final concentration of 10 U/ml. On day 6, cell proliferation was measured by counting the incorporation of [3H]TdR pulsed for the final 8 hr. CD44+ cells were depleted using Dynabeads M450 sheep anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG; Dynal, Oso, Norway) after staining with anti-CD44 (IM7, rat IgG) monoclonal antibody (mAb).

Flow cytometric analysis and mAb used for a flow cytometric analysis comprised fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-IL-2Rβ (CD122) mAb (TM-β1; Seikagaku Kogyo Co., Tokyo, Japan), FITC-conjugated CD44 mAb (1M7; PharMingen, San Diego, CA), phycoeryhrin (PE)-conjugated anti-TCRβ-chain mAb (H57.597: PharMingen) and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD8 mAb (53-6.7; PharMingen). The cells were incubated with various combinations of mAb before being analysed by a FACSCalibur flow cytometer with the CELLQuest program (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Just before being run on the cytometer, 50 µg/ml of propidium iodide (PI) were added to the cell suspension to exclude any dead cells.

Cytotoxic and CTL frequency assays

The assay of cytolytic activity was carried out using an ordinary 51Cr-release assay, as previously reported.11 The frequency of TRP-2180-188-reactive T-cell precursors was determined by limiting dilution assay. NW non-adherent or NW non-adherent and CD44+ cell-depleted spleen cells from B6 naïve mice were plated in 96-well round plates with irradiated B6 spleen cells (4 × 104/well), the TRP-2180-188 peptide (5 µm) and IL-2 (10 U/ml). On day 3, one half of the medium was changed, with the complete medium containing 20 U/ml IL-2. On day 6, half the medium was removed and 51Cr-labelled 1 × 104 EL4 cells, pulsed with the TRP-2180-188 peptide at a dose of 5 µm, were added to the wells. After 4 hr incubation, the supernatants were collected and the levels of 51Cr-release were determined. Each group consisted of 10 wells and the wells whose 51Cr-release were less than mean ±3 SD of the wells with labeled target alone were determined to be negative.

Preperation of ATX-BM mice

The recipient female Thy1.1+ B10 mice were thymectomized in an anaesthetized condition. After 1 month, they were lethally irradiated (10 Gy) and injected intravenously with 5 × 106 T-cell depleted bone marrow cells from Thy1.2+ B6 mice on the same day. Two months after bone marrow transfer, the ATX-BM mice were used for the experiments.

In vitro proliferation assay using the spleen cells from ATX-BM mice

To examine the presence of TRP-2-recognizing T cell precursors in ATX-BM mice, the spleen cells (2·5 × 105/well) were cultured with irradiated B6 spleen cells (2·5 × 105/well) with the peptides at a dose of 5 µm in 96-well flat plates. On day 3, IL-2 was added into the wells at a final concentration of 10 U/ml. On day 6, cell proliferation was measured by counting the incorporation of [3H]TdR pulsed for the final 8 hr.

Induction of TRP-2-reactive T cells from the spleen cells of ATX-BM mice

The spleen cells (2·5 × 106/well) from the ATX-BM mice were first cultured with irradiated B6 spleen cells (2·5 × 106/well) and the TRP-2180-188 peptide at a dose of 5 µm without IL-2 in 24-well plates. On day 3, IL-2 was added to a final concentration of 10 U/ml. On day 7, the enriched viable cells were re-cultured at a dose of 5 × 105/well with 5 × 106 25 Gy-irradiated B6 spleen cells, which were pulsed with 5 µm TRP-2180-188 peptide. On day 9, IL-2 was added at a final concentration of 10 U/ml. Six days after the second stimulation, the viable cells were harvested and used for a flow cytometric analysis and the in vitro stimulation assay. To examine the capacity of the cultured cells to produce IFN-γ, they (1 × 105/well) were cultured with EL4 cells (1 × 104/well), which were pulsed with several doses of the TRP-2180-188 peptide in a 96-well round plate. After 24 hr culture, the level of IFN-γ in the supernatant was determined using ELISA.

Statistics

The statistical significance of the data was determined using Student's U-test. A P-value less than 0·05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The responses of TRP-2180-188-recognizing T cells with high or low avidity

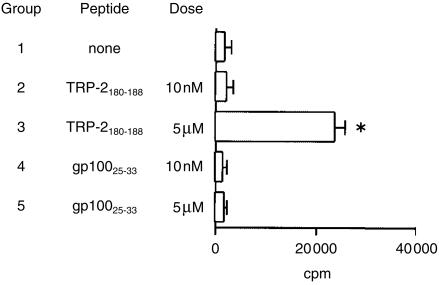

The avidity of T cells is influenced by several factors such as peptide dose or culture duration.19 Interestingly, Zeh et al. reported that naïve B6 spleen cells, which were cultured with a high dose (10 µm) of the TRP-2180-188 peptide, can generate low avidity CTL, but that the culture of the immunized B6 spleen cells with a low dose (1 nm) of the TRP-2180-188 peptide resulted in the generation of high avidity CTL.12 At first, we tried to confirm that MDA-reactive T-cell precursors could be detected in naïve B6 mice. The spleen cells from naïve B6 mice were cultured with two peptides of MDA, the TRP-2180-188 and gp10025-33 peptides, both of which are known to be antigens recognized by B16 melanoma-reactive CTLs.8,18 Figure 1 shows that cell proliferation was only detected when the spleen cells from naïve B6 mice were cultured with the TRP-2180-188 peptide at a dose of 5 µm. No proliferation was detected when cultured with the TRP-2 peptide at a dose of 10 nm. In addition, no proliferation in response to the gp100 peptide was observed at both doses of the peptides. These results suggest that the T-cell precursors recognizing the TRP-2180-188 peptide, but not the gp10025-33 peptide, existed in naïve B6 mice at a relatively high frequency.

Figure 1.

TRP-2180-188-recognizing T cells in naïve B6 spleen cells. The whole spleen cells from B6 naïve mice were cultured with the indicated peptides. On day 3, IL-2 was added to the well at a final concentration of 10 U/ml. On day 6, cell proliferation was measured by counting the incorporation of [3H]TdR pulsed for the final 8 hr. * P < 0·05 significant compared with the other groups. Similar results were obtained in two separate experiments.

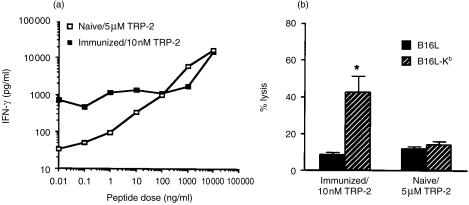

We next prepared TRP-2-recognizing T cells with either a high or low avidity. To generate low avidity T cells, the spleen cells from naïve B6 mice were cultured with a high dose (5 µm) of the TRP-2180-188 peptide. To generate high avidity T cells, the spleen cells from the B6 mice, which were twice immunized with irradiated GM-CSF-producing B16 melanoma, were cultured with a low dose (10 nm) of the TRP-2180-188 peptide, was examined. After four stimulations, the capacity of the cultured cells to produce IFN-γ in response to the stimulator cells, pulsed with several doses of the TRP-2180-188 peptide, was examined. As shown in Fig. 2(a)), low avidity T cells produced IFN-γ in a dose dependent manner. They produced a low level of IFN-γ when stimulated with the EL4 cells pulsed with lower doses (< 10 nm) of the TRP-2 peptide. In contrast, high-avidity T cells produced a considerable level of IFN-γ even when stimulated with the EL4 cells pulsed with a low dose of the TRP-2 peptide. We further examined the cytolytic activity of these T cells (Fig. 2b). The T cells with high avidity did not kill B16L, a class I negative variant of B16 melanoma, but did kill B16L-Kb, H-2Kb-transfected B16L cells. On the other hand, the T cells with low avidity showed no difference in the cytolytic activity against B16L and B16L-Kb.

Figure 2.

The responses of TRP-2180-188-recognizing T cells with high or low avidity. (a) To generate low avidity T cells, the spleen cells from naïve B6 mice were repeatedly stimulated with the TRP-2180-188 peptide at a dose of 5 µm. To generate high avidity T cells, the spleen cells of B6 mice, which were twice immunized with irradiated GM-CSF-producing B16 melanoma, were repeatedly stimulated with the TRP-2180-188 peptide at a dose of 10 nm. Six days after the fourth stimulation with the peptide, the viable cells were cultured for 24 hr with the EL4 cells pulsed with the indicated doses of TRP-2180-188 peptide. The level of IFN-γ in the supernatant was determined by ELISA. The levels of IFN-γ in the cultures of high and low avidity T cells with the EL4 cells without the TRP-2 peptide were 20 and less 16, respectively. (b) Six days after the fourth stimulation with the peptide, the viable cells were examined for any cytolytic activity against B16L and B16L-Kb. B16L is an MHC class I loss variant of B16 melanoma and B16L-Kb is a subline of B16L transfected with H-2Kb gene. The 4 hr cytolytic assay was performed at an E/T ratio of 10/1. *P < 0·05 significant compared with the other groups.

Anti-TRP-2180-188-reactive CD8+ T-cell precursors in naïve B6 mice express CD44 and CD122 molecules

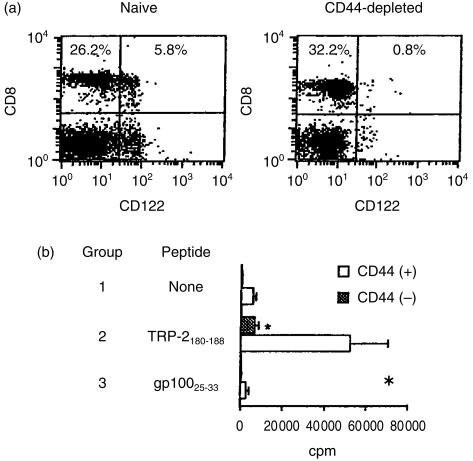

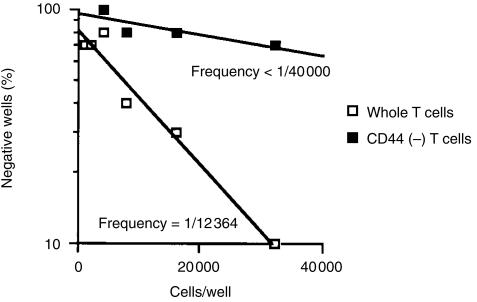

Because TRP-2 is a non-mutated MDA recognized by melanoma-reactive T cells,8,9 TRP-2-reactive T cells can thus be regarded as self-antigen-reactive. On the other hand, recent reports suggest that self antigen-reactive CD8+ T cells could develop via the extrathymic pathway,15,16 while in addition, that their surface phenotypes are positive for both CD122 (IL-2Rβ) and CD44.15,17 Based on these findings, we tried to determine whether TRP-2-reactive T-cell precursors in naive B6 mice express CD44 and CD122 molecules. The selective depletion of CD44+ cells from NW non-adherent spleen cells from naïve B6 mice clearly decreased the percentage of CD122+ CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3a). We next determined whether the prior depletion of CD44+ cells could have any influence on the in vitro proliferation of B6 naïve spleen cells against the TRP-2 peptide. As shown in Fig. 3(b)), the selective depletion of CD44+ cells resulted in a dramatic decrease in anti-TRP-2180-188 response of splenic T cells from naïve B6 mice. Presumably, the low level of anti-TRP-2180-188 response of NW non-adherent CD44+ cell-depleted cells was due to an incomplete depletion of CD44+ cells. In contrast, no proliferative response to the gp10025-33 peptide was observed in either group. Furthermore, using a limiting dilution assay, we confirmed that TRP-2180-188-reactive T-cell precursors in naïve B6 spleen cells were CD44 positive. Figure 4 shows that the frequency of TRP-2180-188-reactive T-cell precursors in naïve B6 spleen cells apparently decreased by the selective depletion of CD44+ cells. Taken together, these results indicate that TRP-2180-188-reactive T-cell precursors in B6 naïve spleen cells express both CD122 and CD44 molecules, in a similar manner to that of extrathymically developed T cells.15,17

Figure 3.

TRP-2-recognizing T-cell precursors in B6 naïve spleen cells express both CD44 and CD122 molecules. (a) NW non-adherent or NW non-adherent and CD44+ cell-depleted spleen cells from naïve B6 mice were examined for the expression of CD8 and CD122. (b) NW non-adherent or NW non-adherent and CD44+ cell-depleted spleen cells (5 × 104/well) from naïve B6 mice were cultured with irradiated B6 spleen cells (5 × 105/well) in the presence of either the TRP-2180-188 or gp10025-33 peptide at a dose of 5 µm. On day 3, IL-2 was added to the well at a final concentration of 10 U/ml. On day 6, cell proliferation was measured by counting the incorporation of [3H]TdR pulsed for the final 8 hr. * P < 0·05 significant compared with the other groups. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

Figure 4.

The frequency of TRP-2180-188-reactive T-cell precursors in naïve B6 spleen cells. NW non-adherent or NW non-adherent and CD44+ cell-depleted spleen cells from naïve B6 mice were cultured with irradiated B6 spleen cells (4 × 104/well) and the TRP-2180-188 (5 µm) in 96-well round plates with IL-2 (10 U/ml). On day 3, the half medium was changed with the complete medium containing 20 U/ml IL-2. On day 6, 51Cr-labelled 1 × 104 EL4 cells, pulsed with the 5 µm TRP-2180-188 peptide, were added to the well and the negative wells were determined. Each group consisted of 10 wells and the wells whose 51Cr-release were less than mean ±3 SD of the wells with target alone were determined to be negative. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

Generation of TRP-2180-188-reactive T cells from ATX-BM mice

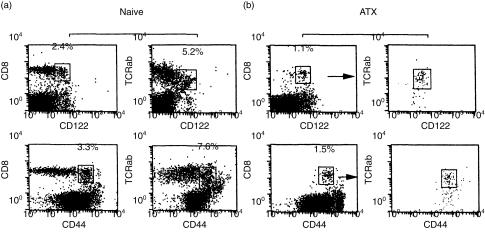

To directly examine the possibility that the TRP-2180-188-reactive T cells could develop extrathymically, we prepared mice lacking intrathymically developed T cells. Thy1.1+ B10 mice were adult thymectomized, lethally irradiated and reconstituted by T-cell depleted bone marrow cells from Thy1.2+ B6 mice. Two months later, their CD8+ T cells in the periphery were confirmed to be Thy1.2+ donor-derived cells (Fig. 5). Figure 6 shows representative findings of a flow cytometric analysis of the spleen cells from naïve B6 or ATX-BM mice. The spleen cells from naïve B6 mice contained CD8+ CD122+ or CD8+ CD44+ T cells. In addition, they also contained intermediate TCR αβ+ CD122+ T cells. The expression of natural killer (NK)1.1 antigen on CD8+ CD122+ or CD8+ CD44+ T cells was negative (data not shown). These results are consistent with those of a previous report,20 and we have already reported that extrathymically developed CD8+ T cells in H-Y antigen-specific TCR transgenic mice are negative for NK1.1 expression on CD8+ CD122+ T cells or CD8+ CD44+ T cells.17 On the other hand, in the ATX-BM mice, CD8+ T cells expressed both CD122 and CD44 molecules (Fig. 6b). The CD8+ CD122+ splenic T cells from the ATX-BM mice expressed intermediate TCRαβ. In addition, the intermediate TCRαβ+ cells were CD8+ CD44+. In total, these results indicate that CD8+ CD44+ T cells were CD122+ and that the subset of CD8+ CD122+ cells were almost identical to that of CD8+ CD44+ cells.

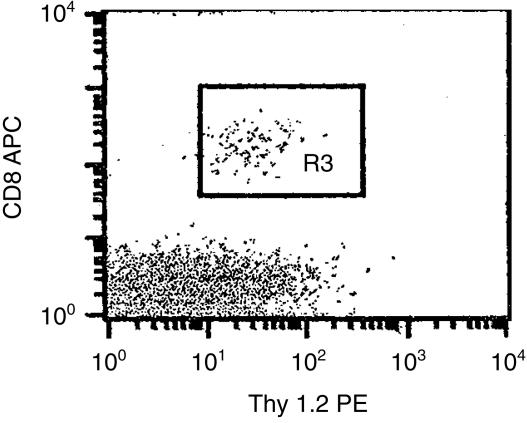

Figure 5.

Extrathymic origin of the CD8+ T cells in the ATX-BM mice. Thy1.1+ B10 mice were adult thymectomized, irradiated and reconstituted with T-cell depleted bone marrow cells from Thy1.2+ B6 mice. Two months after bone marrow reconstitution, the expressions of CD8 and Thy1.2 on their peripheral blood lymphocytes were examined. They were stained with PE-conjugated anti-Thy1.2 and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD8 mAb.

Figure 6.

The phenotypes of spleen cells from naïve B6 mice or the ATX-BM mice. Thy1.1+ B10 mice were adult thymectomized, irradiated and reconstituted with T-cell depleted bone marrow cells from Thy1.2+ B6 mice. Two months after bone marrow reconstitution, the expressions of CD122, CD44, CD8 and TCR αβ on the spleen cells from naïve B6 mice (a) or the ATX-BM mice (b) were examined. In the case of the ATX-BM mice (b), the gated subset of either CD8+ CD122+ or CD8+ CD44+ T cells, as shown by the arrow, was examined for their expression of TCR αβ using two-colour cytometry. The result are a representative of 3 mice experiments.

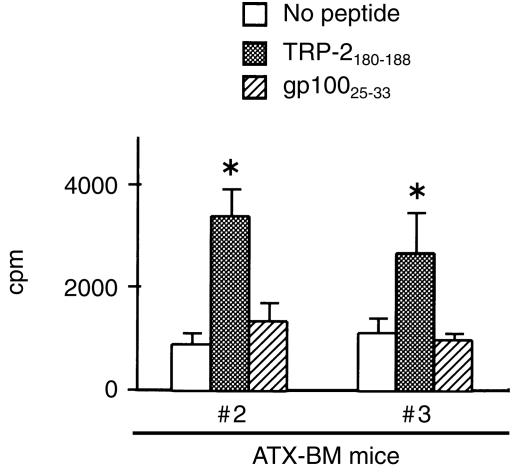

We next determined whether TRP-2-recognizing T-cell precursors could exist in these ATX-BM mice. In a preliminary experiment, the spleen cells from ATX-BM mouse #1 were cultured with the peptides (5 µm) with IL-2 (10 U/ml), but any antigen-specific proliferation was observed (data not shown). Next, the spleen cells from ATX-BM mice #2 and #3 were cultured with the peptides with IL-2 in the presence of irradiated syngeneic spleen cells (Fig. 7). As a result, T-cell precursors recognizing the TRP-2180-188 peptide, but not the gp10025-33 peptide, were found to exist in the spleen cells of the ATX-BM mice.

Figure 7.

The spleen cells from ATX-BM mice contain TRP-2-recognizing T-cell precursors. Two months after bone marrow reconstitution, the spleen cells (2·5 × 105/well) from ATX-BM mice #2 and #3 were individually cultured with irradiated B6 spleen cells (2·5 × 105/well) with the TRP-2180-188 or gp10025-33 peptide at a dose of 5 µm in 96-well flat plates. On day 3, IL-2 was added into the wells at a final concentration of 10 U/ml. On day 6, cell proliferation was measured by counting the incorporation of [3H]TdR pulsed for the final 8 hr. *P < 0·05 significant compared with the other groups.

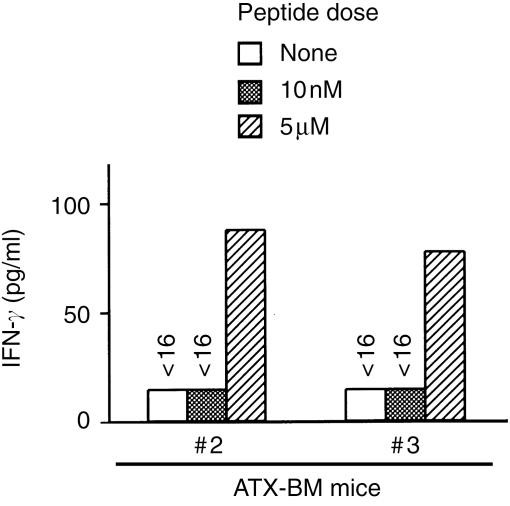

We further determined whether extrathymically developed T cells recognizing the TRP-2 peptide could produce IFN-γ production in response to the TRP-2 peptide. The spleen cells of the ATX-BM mice #2 and #3 were cultured in vitro with both TRP-2 peptide and IL-2 (10 U/ml), as well as irradiated B6 spleen cells. Six days after the 2nd stimulation, the cultured cells were harvested and their antigen-specific IFN-γ production was examined by a culture with the EL4 cells, pulsed with different doses of the TRP-2180-188 peptide. As shown in Fig. 8, the cultured spleen cells from ATX-BM mice #2 and #3 produced a low but definite level of IFN-γ in response to the EL4 cells only when pulsed with 5 µm, but not with 10 nm, of the TRP-2180-188 peptide.

Figure 8.

TRP-2-specific IFN-γ production of the cultured spleen cells from the ATX-BM mice. The spleen cells from the ATX-BM mice were in vitro stimulated with the TRP-2180-188 peptide, as described in Materials and methods. Six days after the second stimulation, the viable cells (1 × 105/well) were harvested and cultured with the EL4 cells (1 × 104/well), pulsed with the indicated doses of TRP-2180-188 peptide, in a 96-well round plate for 24 hr. The level of IFN-γ in the supernatant was determined by ELISA.

Discussion

Recent advances in tumour immunology has revealed that self-antigens on human cancer are the most prevalent antigens recognized by the immune system,2–6 and a better understanding of the balance between tumour immunity and autoimmunity is thus necessary.1,7,21 In melanoma patients, efficient tumour control in human patients is associated with autoimmunity, such as observed in vitiligo.22 In murine models, one report suggested the possibility of inducing an antitumour T-cell response without autoimmunity,23 but another report showed that immunotherapy with dendritic cells directed against tumour antigen shared with normal cells results in severe autoimmune disease.24 Although these reports focused on relationship between tumour immunity and autoimmunity, no one has previously referred to the development of autoreactive and tumour antigen-recognizing T cells.

The significant presence of T-cell precursors specific to a self-antigen, TRP-2, in naïve mice and their failure in rejecting melanoma have not yet been fully elucidated. Interestingly, similar observations have been reported in humans. Anti-melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART)-1 (anti-MART-1) CTL precursors are detectable in healthy donors,25 and the T-cell responses of melanoma patients to MART-1 antigen have not been reported to correlate with the clinical responses.26 Interestingly, Loftus et al. reported the data suggesting that the relatively high frequency of anti-MART-1 CTL may result from cross-reactivity of these T cells with either self antigens or relatively ubiquitous foreign epitopes.27 Furthermore, they suggested that anti-MART-1 CTL could not exhibit an efficient antimelanoma T-cell response in vivo because these antigens and epitopes can function as partial agonists or antagonists.28 However, although the situation is different between humans and mice, our findings in this study may provide an alternative explanation. That is, the prevalent presence of TRP-2-recognizing T-cell precursors in naïve mice may be ascribed to their extrathymic development. In addition, the failure to elicit an effective T-cell response in vivo may be due to their low avidity, as a result of their extrathymic development. In support of this idea, extrathymically developed H-Y antigen-reactive CD8+ T cells in H-Y antigen-specific TCR transgenic mice show no response to male stimulator cells, which are naturally presenting the H-Y epitope, but can be stimulated by anti-TCR mAb.17 In addition, such extrathymically developed T cells could show a response to stimulator cells, when pulsed with a high dose of the H-Y peptide (unpublished data). We suppose that extrathymically developed TRP-2-recognizing T cells with low avidity can participate in the antitumour immune response, not as antigen-specific T cells but as non-specific effector cells such as NK cells. This is because extrathymically developed T cells can proliferate and produce IFN-γ in response to IL-2 or IL-15, independent of antigen stimulation, because of their spontaneous expression of IL-2Rβ chain (CD122).29

The T-cell responses of the ATX-BM mice against the TRP-2 peptide were about 10-fold lower than those of naïve mice, although the number of CD8+ CD44+ or CD8+ CD122+ T cells in the former mice were almost half of the latter mice. This might suggest the possibility that up to 90% of the low avidity TRP-2-reactive T cells in naïve mice could require a thymus for development. In regards with this observation, one possibility is that a lack of CD4+ T cells in the ATX-BM mice, judged from the results of Fig. 6(b)), decreased their CD8+ T-cell responses. The presence of irrelevant CD4+ T cells could help antigen-specific responses of CD8+ T cells probably through bystander cytokine help. Another possibility is that the splenic cells from the ATX-BM mice contained suppressive cells. Indeed, many fibroblastic and large-sized cells were observed in the cultured cells from the ATX-BM mice by microscopy (data not shown). However, we have no clear answer to explain the low T-cell responses of the splenic cells from the ATX-BM mice. In addition, as shown in Fig. 3, the selective depletion of CD8+ CD44+ or CD8+ CD122+ cells in naïve spleen cells, which means the removal of extrathymically developed CD8+ T cells, resulted in about 1/5 of the T-cell response against the TRP-2 peptide. This result suggests that a main population of CD8+ T cells, capable of responding to the TRP-2 peptide in the naïve B6 mice, was CD44+ or CD122+. Therefore, we could rule out the possibility that the low avidity TRP-2-reactive T cells in naïve mice are thymus-dependent.

Extrathymically developed CD8+ T cells in naïve mice are CD44+ and CD122+. This might suggest the possibility that chronic stimulation of thymus-dependent T cells by a cross-reactive antigen could account for the presence and phenotype of CD8+ CD44+ or CD8+ CD122+. However, this population could be detected in thymectomized male mice which were reconstituted with bone marrow cells of mice transgenic for male H-Y antigen-specific TCR.17 Because H-Y antigen is known not to be cross-reactive, we suppose that expression of CD44 and CD122 molecules on extrathymically developed T cells did not result from chronic stimulation of thymus-dependent T cells by cross-reactivity.

Although one report previously suggested that low avidity T cells recognizing a model tumour-antigen can show an antitumour T-cell response,20 high avidity T cells have a superior in vitro and in vivo antitumour efficiency in the murine model.12 A similar observation has been made with CTL clones specific for human gp100 peptide.30 These lines of evidence imply that methods of in vivo vaccination that activate large numbers of low avidity T cells may not be useful because they could not recognize naturally presented tumour antigens. In fact, immunization with high doses of peptide epitopes has been reported to result in the induction of epitope-specific tolerance and enhanced tumour growth in vivo.31 For successful antitumour vaccination with peptides, further studies are needed to explore the methods to selectively activate tumour-antigen recognizing high avidity T cells in vivo.

Abbreviations

- ATX-BM

adult thymectomized and bone marrow reconstituted

- IL-2Rβ

interleukin-2R β chain

- MDA

melanocyte differentiation antigen

- NW

nylon wool

- TRP

tyrosinase-related protein

References

- 1.Houghton AN. Cancer antigens: immune recognition of self and altered self. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1–4. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, et al. Identification of a human melanoma antigen recognized by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6458–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, Robbin PF, Rivoltini L, Topalian SL, Miki T, Rosenberg SA. Cloning of the gene coding for a shared human melanoma antigen recognized by autologous T cells infiltrating into tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3515–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brichard V, Van Pel A, Wolfel T, Wolfel C, De Plaen E, Lethe B, Coulie PG, Boon T. The tyrosinase gene codes for an antigen recognized by autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. J Exp Med. 1993;178:489–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg SA. A new era for cancer immunotherapy based on the genes that encode cancer antigens. Immunity. 1999;10:281–7. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde B. Tumor antigens recognized by T cells. Immunol Today. 1997;81:267–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardoll DM. Inducing autoimmune disease to treat cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5340–2. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloom MB, Perry-Lalley D, Robbins FP, Li Y, El-Gamil M, Rosenberg SA, Yang JC. Identification of tyrosinase-related protein 2 as a tumor rejection antigen for the B16 melanoma. J Exp Med. 1997;185:453–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang RF, Appella E, Kawakami Y, Kang X, Rosenberg SA. Identification of TRP-2 as a human tumor antigen recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2207–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkhurst MR, Fitzgerald EB, Southwood S, Sette A, Rossenberg SA, Kawakami Y. Identification of a shared HLA-A *0201-restricted T-cell epitope from the melanoma antigen tyrosinase-related protein 2 (TRP2) Cancer Res. 1998;58:4895–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harada M, Tamada K, Abe K, et al. Characterization of B16 melanoma-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;47:198–204. doi: 10.1007/s002620050521. 10.1007/s002620050521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeh HJ, II, Perry-Lalley I, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA, Yang JC. High avidity CTLs for two self-antigens demonstrate superior in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy. J Immunol. 1999;162:989–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Q, Walker RB, Girao C, Opferman JT, Sun J, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Ashton-Rickardt PG. Specific recognition of thymic self-peptides induces the positive selection of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1997;7:221–31. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodes RJ, Sharrow SO, Solomon A. Failure of T cell receptor Vβ negative selection in an athymic environment. Science. 1989;246:1041–4. doi: 10.1126/science.2587987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato K, Ohtsuka K, Hasegawa K, Yamagiwa S, Watanabe H, Asakura H, Abo T. Evidence for extrathymic generation of intermediate T cell receptor cells in the liver revealed in thymectomized, irradiated mice subjected to bone marrow transplantation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:759–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocha B, Vassalli P, Guy-Grand D. The Vβ repertoire of mouse gut homodimeric αCD8+ intraepithelial T cells receptor α/β+ lymphocytes reveals a major extrathymic pathway of T cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 1991;173:483–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada H, Ninomiya T, Hashimoto A, Tamada K, Takimoto H, Nomoto K. Positive selection of extrathymically developed T cells by self-antigens. J Exp Med. 1998;188:779–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overwijk WW, Tsung A, Irvine KR, et al. Gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: induction of ‘self’-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med. 1998;188:277–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander-Miller MA, Leggartt GR, Sarin A, Berzofsky JA. Role of antigen, CD8, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) avidity in high dose antigen induction of apoptosis of effector CTL. J Exp Med. 1996;184:485–492. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe H, Miyaji M, Kawachi Y, Iiai T, Ohtsuka K, Iwanaga T, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Abo T. Relationships between intermediate TCR cells and NK1.1+ T cells in various immune organs. J Immunol. 1995;155:2972–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowne WB, Srinivasan R, Wolchok JD, Hawkins WG, Blachere NE, Dyall R, Lewis JJ, Houghton AN. Coupling and uncoupling of tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1717–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg SA, White DE. Vitiligo in patients with melanoma: normal tissue antigens can be targets for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother. 1996;19:81–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan DJ, Kreuwel HT, Fleck S, Levitsky HI, Pardoll DM, Sherman LA. Activation of low avidity CTL specific for a self epitope resulted in tumor rejection but not autoimmunoty. J Immunol. 1998;160:643–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludewig B, Ochsenbein AF, Odermatt B, Paulin D, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Immunotherapy with dendritic cells directed against tumor antigens shared with normal host cells resulted in severe autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2000;191:795–803. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pittet MJ, Valmori D, Dunbar PR, et al. High frequencies of naïve Melan/MART-1-specific CD8+ T cells in a large proportion of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2 individuals. J Exp Med. 1999;190:705–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Jennings C, et al. Recognition of multiple epitopes in the human melanoma antigen gp100 by tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor regression. J Immunol. 1995;154:3961–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loftus D, Castelli C, Clay T, et al. Identification of epitope mimics recognized by CTL reactive to the melanoma/melanocyte-derived peptide MART-1 (27–35) J Exp Med. 1996;184:647–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loftus DJ, Squarcina P, Nielsen M-B, et al. Peptides derived from self-proteins as partial agonists and antagonists of human CD8+ T-cell clones reactive to melanoma/melanocyte epitope MART-1 27–35. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2433–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada H, Nakamura T, Matsuzaki G, Iwamoto Y, Nomoto N. TCR-independent activation of extrathymocally developed, self antigen-specific T cells by IL-2/IL-15. J Immunol. 2000;164:1746–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dudley ME, Nishimura MI, Holt AKC, Rosenberg SA. Anti-tumor immunization with a minimal peptide epitope (G9-209-2M) leads to a functionally heterogenous CTL response. J Immunother. 1998;22:288–98. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toes RE, Blom RJ, Iffringa R, Kast WM, Melief CW. Enhanced tumor outgrowth after peptide vaccination. Functional deletion of tumor-specific CTL induced by peptide vaccination can lead to the inability to reject tumors. J Immunol. 1996;156:3911–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]