Abstract

The role of inflammatory effector cells in the pathogenesis of airway allergy has been the subject of much investigation. However, whether systemic factors are involved in the development of local responses in both upper and lower airways has not been fully clarified. The present study was performed to investigate aspects of the pathogenesis of isolated allergic rhinitis in a murine model sensitized to ovalbumin (OVA). Both upper- and lower-airway physiological responsiveness and inflammatory changes were assessed, as well as bone marrow progenitor responses, by culture and immunohistological methods. Significant nasal symptoms and hyper-responsiveness appeared after intranasal OVA challenge (P < 0·0001 and P < 0·01, respectively), accompanied with significant nasal mucosal changes in CD4+ cells (P < 0·001), interleukin (IL)-4+ cells (P < 0·01), IL-5+ cells (P < 0·01), basophilic cells (P < 0·02) and eosinophils (P < 0·001), in the complete absence of hyper-responsiveness or inflammatory changes in the lower airway. In the bone marrow, there were significant increases in CD34+ cells, as well as in eosinophils and basophilic cells. In the presence in vitro of mouse recombinant IL-5, IL-3 or granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), the level of bone marrow eosinophil/basophil (Eo/Baso) colony-forming cells increased significantly in the OVA-sensitized group. We conclude that, in this murine model of allergic rhinitis, haemopoietic progenitors are upregulated, which is consistent with the involvement of bone marrow in the pathogenesis of nasal mucosal inflammation. Both local and systemic events, initiated in response to allergen provocation, may be required for the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis. Understanding these events and their regulation could provide new therapeutic targets for rhinitis and asthma.

Introduction

We and others have shown that murine bone marrow eosinophil progenitors are upregulated during the induction of lower airway inflammation and hyper-responsiveness by ovalbumin (OVA).1,2 These observations, together with our findings in human allergic rhinitis and asthma and in canine allergic airway inflammation,3–10 demonstrating the active recruitment and specific upregulation of blood and bone marrow progenitors in these processes, have led us to postulate that a key mechanism underlying inflammatory cell recruitment to the airways is the initiation and maintenance of proliferation and differentiation of haemopoietic progenitors. Many studies using animal models of airway inflammation have focused on the lower airway, utilizing the nasal passages only to deliver large doses of antigen to the lung, while some murine studies have focused only on nasal responses without verification of changes in the lower airway.11–13 The present study was aimed at investigating links between haemopoietic processes and ‘pure’ upper airway inflammation in the nasal mucosa, in the absence of lower airway inflammation. When both upper and lower airway changes co-occur, it is difficult to assess the role of haemopoietic processes in the development of each compartment in isolation; therefore, we decided to establish an experimental murine allergic rhinitis as a model to define the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis in isolation. We examined the role of bone marrow responses in this model, in which upper (but not lower) airway inflammation was induced.

In the present study, four groups of animals were studied (non-sensitized; sensitized, but without nasal antigen challenge; sensitized and administered daily nasal antigen challenge for 1 week; sensitized and administered daily nasal antigen challenge for 2 weeks) in order to clarify the relationship of haemopoietic responses to the various phases of sensitization and challenge with antigen.

Materials and Methods

Animals and OVA sensitization

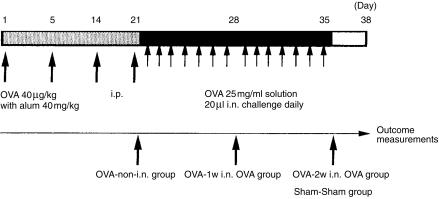

Male and female 8–10-week-old BALB/c mice (Charles River Therion, Troy, NY), housed under specific pathogen-free conditions, were sensitized using OVA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), as shown in Fig. 1 and described as follows. Forty µg/kg of OVA, diluted in sterile normal saline containing aluminium hydroxide gel (alum adjuvant, 40 mg/kg), was administered to non-anaesthetized animals four times (on days 1, 5, 14, 21) by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, followed by daily intranasal (i.n.) challenge with OVA diluted in sterile normal saline (20 µl per mouse of a 25 mg/ml solution of OVA) from day 22 onwards (Fig. 1). Mice were divided into four groups:

OVA-2w i.n. OVA group, i.e. mice challenged with OVA via the i.n. route from day 22 to day 35 after sensitization (day 1 to day 21).

OVA-1w i.n. OVA group, i.e. mice challenged with OVA via the i.n. route from day 22 to day 28 after sensitization.

OVA-non-i.n. group, i.e. mice sensitized but not challenged intranasally.

Sham-Sham group, i.e. mice treated with diluent during both sensitization and challenge.

Figure 1.

Protocol for ovalbumin (OVA) sensitization and subsequent OVA intranasal (i.n.) challenge. OVA-2w i.n. OVA group: mice in which OVA challenge was given intranasally from day 22 to day 35 after sensitization from day 1 to day 21. OVA-1w i.n. OVA group: mice that were challenged with OVA from day 22 to day 28 after sensitization. OVA-non-i.n. group: mice that were given sensitization without OVA challenge. Sham-Sham group: mice treated with diluent, during both sensitization and challenge, instead of with OVA. i.p., intraperitoneal.

Clinical symptoms, airway responsiveness and specimens

Nasal histamine responsiveness was measured by determining the concentration of histamine that caused sneezing and itching. Nasal challenges with 10 µl of serially diluted histamine solution or saline were administered. Sneezes and nasal itching motions (nasal rubbing) were counted and the point noted at which these were significantly higher than those associated with the normal saline control. This was expressed as the limiting concentration of histamine (log10 pg/ml), and measured on day 29 for the OVA-1w i.n. OVA group and on day 36 for the OVA-2w i.n. OVA group and Sham-Sham group.

Nasal symptoms were evaluated by counting the number of sneezes and nasal rubbing that occurred in the 10 min after OVA i.n. provocation, by the same dose of OVA as given during daily challenge, on day 31 for the OVA-1w i.n. OVA group and on day 38 for the OVA-2w i.n. OVA group; Sham-Sham group animals were also given diluent on day 38.

Twenty-four hours after intranasal provocation, lower airway responsiveness was measured; this was performed on day 32 for the OVA-1w i.n. OVA group (n = 5) and on day 39 for both of groups 1 (n = 5) and 4 (n = 5). The method used, as previously reported,1,14 was based on the measurement of total pulmonary resistance (RRS) to increasing intravenous (i.v.) doses of methacholine, using a flow interrupter technique that was modified for use in mice. Mice were killed, 24 hr post-i.n. provocation with OVA or diluent, by cardiac puncture after induction of deep anaesthesia, using a solution that contained ketamine hydrochloride (Ketalean®; Bimeda-MTC, Animal Health Inc., Cambridge, Ont., Canada) and xylazine (Rompun®; Bayer Inc. Agriculture Division, Animal Health, Toronto, Ont., Canada), diluted in sterile normal saline. Nasal mucosa, tracheal mucosa, lung tissue, femoral and sternal bone marrow were removed and processed immediately. The OVA-1w i.n. OVA group mice were also used for kinetic studies; after daily i.n. OVA challenge from days 22–28, followed by a 5-day recovery interval, i.n. OVA provocation was performed on day 34, and the tissues described above were sampled prior to challenge and 1, 4, 10 and 24 hr postchallenge (n = 5 at each time-point, total n = 25).

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of McMaster University.

Tissue preparation

Nasal mucosal, tracheal and lung tissues were treated using methods previously described.15 Briefly, specimens were cut into 3–4-mm3 pieces and fixed overnight at −20° in cold acetone containing protease inhibitors, prior to processing in glycolmethacrylate (GMA) resin. The embedded tissues were cut into 4-µm thin sections using a microtome for ultra-thin sections (Ultra Cut; Leica, Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Bone marrow cells were obtained from femoral and sternal bone marrow separately, suspended in McCoys 3+ culture medium, as previously described,1 and cell numbers were counted in cell pellets. Both total bone marrow cells and mononuclear cells were separated by density-gradient centrifugation over LymphoPrep (NYCOMED Pharma, Oslo, Norway) for 25 min at 850 g, diluted to a concentration of 5 × 105/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then cytocentrifuge slides were prepared (Cytospin 3; Shandon Scientific, Sewickly, PA) on 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTEX)-coated glass slides. Blood samples were centrifuged at 350 g and the supernatant sera was stored at −20°.

OVA-specific serum immunoglobulin E level

OVA-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) titres in serum were evaluated by a passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) reaction (an 8-day PCA reaction using Wistar rats, as previously reported).13,16 Briefly, the 8-day PCA reaction indicates the serum OVA-specific IgE level in each mouse. Wistar rats were injected intradermally (i.d.), serially with the diluted serum of each mouse, then 8 days later, under xylazine anaesthesia, the rats were injected i.v. with OVA and Evans blue. An i.d. blueing of more than 5 mm diameter was taken to be a positive reaction.

Trypan Blue dye test

To examine the distribution of OVA after intranasal challenge, 20 µl of blue dye solution (Trypan Blue; Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was applied, with or without anaesthesia, as described above in the section entitled ‘Clinical symptoms, airway responsiveness and specimens’ (n = 5 each) and the area of blue staining in the airway was determined 10–60 min postchallenge.

Immunostaining

For differential cell counts of bone marrow on cytocentrifuge slides, the Diff Quick stain (Baxter, McGaw Park, IL) was performed. To identify eosinophils and basophilic cells in the nasal mucosa, tracheal mucosa, bronchial and lung tissue, slides were fixed in acetone–methanol at room temperature for 10 min, then stained in Diff Quick; slides were then embedded in Permount (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). To identify CD4+ lymphocytes, immunoreactive interleukin (IL)-4+ cells and immunoreactive IL-5+ cells in airway tissues, and CD34+ cells in bone marrow cytocentrifuge preparations, a streptavidin–biotin complex immunostaining system method was employed, using various anti-murine monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): anti-murine CD4 mAb (L3T4, rat immunoglobulin G2a [IgG2a], k; PharMingen Canada, Missisauga, Ont., Canada); anti-murine IL-4 mAb (rat IgG1, k; Genzyme, Cambridge, MA); anti-murine IL-5 mAb (rat IgG1, Genzyme); and anti-murine CD34 mAb (rat IgG2a, k; PharMingen Canada), as previously described but with some modification.15 Briefly, GMA resin-embedded tissue slides and acetone-fixed cytocentrifuge slides were pretreated (to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity) with a solution of 0·1% sodium azide and 0·3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min, washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS), then treated for 30 min with TBS containing 1% skim milk (Carnation; Nestle, Don Mills, Ont., Canada) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL), followed by incubation for 20 min with sterile water saturated with bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma) and 10% normal goat serum in TBS to block non-specific reactivity, and then each mAb was added for 2 hr. Bound antibodies were then labelled with biotinylated second-stage antibodies appropriate to the isotype of each primary antibody (DAKO Canada, Missisauga, Ont., Canada) for 2 hr, and detected using a streptavidin–biotin peroxidase detection system (StreptABComplex/HRP, DAKO Canada). Aminoethylcarbazole (AEC; Sigma) was then applied as a chromogen and the sections were counterstained with Mayer's haematoxylin (Sigma) to contrast with the red positive staining of AEC. A separate set of sections was stained using an avidin–biotin–complex alkaline phosphatase system (VECTASTAIN ABC-AP kit; Vectastain, Burlingame, CA) prior to counterstaining with Methyl Green (Harleco, Philadelphia, PA) to confirm immunoreactivity. Negative control sections were similarly treated with the same isotype immunoglobulin antibody (DAKO Canada), instead of the primary antibody, at a concentration of 25 mg/ml. As a positive control, murine spleen tissue was stained by the same procedure.

Evaluation and quantification of staining

In the lamina propria of the nasal mucosa, all cells expressing positive immunoreactivity for cellular surface markers or any of the intracellular cytokines, were enumerated. The area of the nasal tissue was measured, excluding glands, using an eyepiece with a grid, and the cell count results were expressed as the number of cells/mm2 of lamina propria; the same method of evaluation was employed for lung tissue. For bone marrow evaluation, differential cell counts were performed on cytospin preparations of bone marrow cells after application of the Diff Quick stain; eosinophilic cells and basophilic cells on each slide were enumerated by light microscopy and results were expressed as the number of cells per total cells counted or as a percentage of total femoral or sternal bone marrow cells. CD34+ cells on bone marrow cytospins were also counted by light microscopy: 1000 mononuclear bone marrow cells were counted and the result was expressed as the number of positive cells per total mononuclear cells or percentage of femoral or sternal bone marrow cells.

Bone marrow methylcellulose cultures

Mononuclear cells were isolated, as described above, from the femoral bone marrow of OVA-2w i.n. OVA group and Sham-Sham group mice, then incubated in plastic flasks for 2 hr at 37°, in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2, to remove adherent cells (which interfere with the growth of progenitor cells in semisolid culture). The non-adherent mononuclear cells (NAMNC) were cultured in 35 × 10-mm tissue culture dishes (Falcon Plastics, Oxnard, CA) in a culture medium that comprised 0·9% methylcellulose (The Dow Chemical Company, Midland, MI), 20% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL), Iscove's Dulbecco's medium (with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 0·5 µg of 2-ME and 0·1% BSA) and the following recombinant mouse cytokines (R & D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN): recombinant mouse (rm)IL-5 (0·5, 1, 5, 10 ng/ml) in the presence of 1 × 105 NAMNC, rmIL-3 (0·5, 1, 5, 10 ng/ml) in the presence of 5 × 104 NAMNC, or rm granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (1, 5, 10 ng/ml), in the presence of 2·5 × 104 NAMNC. Following 6 days of culture, colonies of greater than 40 cells were counted using an inverted microscope; eosinophil/basophil colony-forming units (Eo/Baso-CFU) were classified using morphological and histological criteria (tight, compact, round refractile cell aggregates). To confirm the identification of colonies as Eo/Baso-CFU, samples were selected at random from cultures, placed on slides and stained with Diff Quik, as previously described in detail for both human and murine Eo/Baso-CFU.1,2

Statistics

For all cell counts, stained slides were read randomly and in a blinded manner. For analysis of the correlation between clinical symptoms and hyper-responsiveness, Fisher's correlation test was used. The Mann–Whitney U-test was employed for comparison of data between groups, while analysis of variance (anova) was used to evaluate the differences in lower airway hyper-responsiveness.

Results

Clinical symptoms

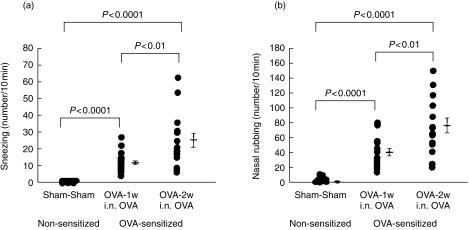

Nasal allergic symptoms, such as sneezing and nasal itching, appeared by day 28 after starting i.n. OVA challenge. Nasal symptoms were accelerated significantly by daily i.n. challenge; sneezing and rubbing were significantly higher in the i.n. daily challenge groups. Fig. 2 (a): number of sneezes/10 min, mean±SE: OVA-2w i.n. OVA group (n = 15): 24·9 ± 4·2, P < 0·0001 compared to the Sham-Sham group (n = 12), P < 0·01 compared to the OVA-1w i.n. OVA group (n = 18); OVA-1w i.n. OVA group: 12·8 ± 1·3, P < 0·0001 compared to the Sham-Sham group; Sham-Sham group: 0·1 ± 0·1. Fig. 2(b): number of nasal rubs/10 min, mean±SE: OVA-2w i.n. OVA group (n = 15): 79·0 ± 9·7, P < 0·0001 compared to the Sham-Sham group (n = 12), P < 0·01 compared to the OVA-1w i.n. OVA group (n = 18); OVA-1w i.n. OVA group: 42·6 ± 5·6, P < 0·0001 compared to the Sham-Sham group; Sham-Sham group: 2·5 ± 1·4.

Figure 2.

Nasal symptoms after ovalbumin (OVA) antigen challenge. The clinical allergic nasal symptoms of (a) sneezing and (b) rubbing, were determined in sensitized mice. OVA-2w i.n. OVA: mice in which OVA challenge was given intranasally from day 22 to day 35 after sensitization from day 1 to day 21. OVA-1w i.n. OVA: mice that were challenged with OVA from day 22 to day 28 after sensitization. Sham-Sham: mice treated with diluent, during both sensitization and challenge, instead of with OVA.

Upper/lower airway responsiveness

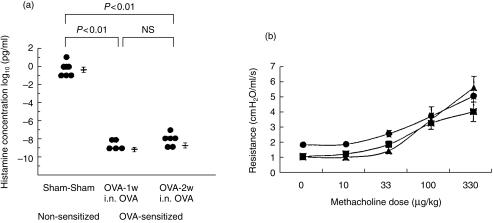

Nasal hyper-responsiveness correlated strongly with clinical symptoms: with sneezing, r = 0·829, P < 0·001; and with itching, r = 0·919, P < 0·0001. Nasal hyper-responsiveness in OVA-sensitized mice was significantly higher than in non-sensitized mice (nasal hyper-responsiveness, log10 pg/ml, mean±SE; OVA-2w i.n. OVA group (n = 6) vs. the Sham-Sham group (n = 6): − 9·2 ± 0·3 vs. −0·3 ± 0·3, P < 0·01; OVA-1w i.n. OVA group (n = 5): − 9·6 ± 0·2, P < 0·01 vs. the Sham-Sham group; NS versus the OVA-2w i.n. OVA group). On the other hand, there was no increase in lower airway hyper-responsiveness in OVA-sensitized mice (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Upper and lower airway responsiveness in sensitized and nonsensitized mice. (a) Nasal histamine responsiveness as represented by the limiting concentration of histamine that caused sneezing and itching. (b) Lower airway responsiveness based on the total lower respiratory system resistance to increasing intravenous doses of methacholine. Filled triangle, ovalbumin (OVA)-2w intranasal (i.n.) OVA group; filled square, OVA-1w i.n. OVA group; filled circle, Sham-Sham group.

Antigen-specific IgE level (PCA titre)

The OVA antigen-specific serum IgE antibody level, as indicated by the 8-day PCA titre of OVA-sensitized mice, ranged from 1 : 84 to 1 : 1028 (OVA-2w i.n. OVA group: 1 : 256–1 : 1028; OVA-1w i.n. OVA group: 1 : 84–1 : 512), while the Sham-Sham group showed no increase in PCA.

Trypan Blue dye test

In challenged, non-anesthetized mice, the distribution of Trypan Blue included nasal mucosa, oral mucosa, pharynx, larynx, subglottic region, and gastrointestinal tract; however, from below the tracheal region to the lower airways, no Trypan Blue staining was observed. In challenged, anaesthetized mice, the entire airway from the nasal cavity to the lungs was stained.

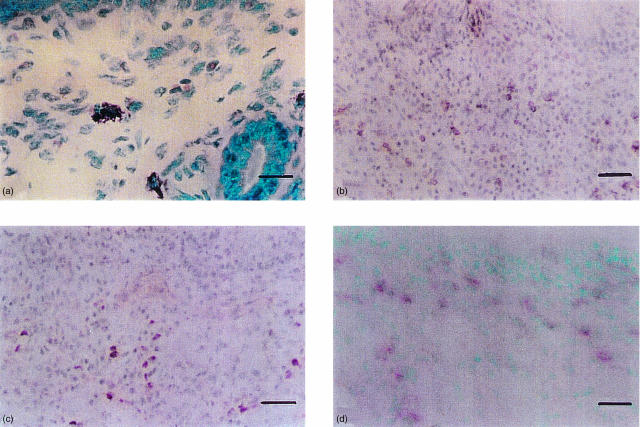

Pathological changes in airway tissue

Significant pathological changes in the nasal mucosa occurred after OVA i.n. daily challenge: increases in the number of eosinophils, CD4+ cells, basophilic cells, IL-4+ cells and IL-5+ cells were observed (Table 1, Fig. 4) (n = 12 each). The numbers of eosinophils and IL-5+ cells were significantly increased in the nasal mucosa as a result of daily i.n. OVA challenge in the OVA-2w i.n. OVA group (see Table 1) as well as in the OVA-1w i.n. OVA group (number of cells/mm2, mean±SE: eosinophils, 76·1 ± 12·0, P < 0·001 versus the Sham-Sham group; IL-5+ cells: 67·1 ± 5·6, P < 0·001 versus the Sham-Sham group). On the other hand, no significant pathological changes were detected in the tracheal mucosa or lung tissue by this method of OVA challenge (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pathological changes in ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized mice

| Sham-Sham group | OVA-2w i.n. OVA group | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory cells in the nasal mucosa | |||

| Eosinophils | 0·0 ± 0·0 | 396·7 ± 77·9 | < 0·001 |

| CD4+ cells | 0·8 ± 0·3 | 46·7 ± 14·4 | < 0·001 |

| Basophilic cells | 10·6 ± 5·0 | 33·5 ± 4·1 | < 0·02 |

| IL-4+ cells | 1·1 ± 0·6 | 115·5 ± 22·0 | < 0·01 |

| IL-5+ cells | 1·6 ± 0·9 | 181·0 ± 35·5 | < 0·01 |

| Inflammatory cells in peripheral lung tissue | |||

| Eosinophils | 0·2 ± 0·2 | 1·3 ± 0·6 | NS |

| CD4+ cells | 116·6 ± 28·0 | 148·4 ± 29·9 | NS |

| Basophilic cells | 0·2 ± 0·2 | 0·5 ± 0·3 | NS |

| IL-4+ cells | 0·3 ± 0·3 | 6·0 ± 4·2 | NS |

| IL-5+ cells | 0·0 ± 0·0 | 0·9 ± 0·5 | NS |

The number of eosinophils, CD4+ lymphocytes, basophilic cells,interleukin (IL)-4+ cells and IL-5+ cells in normal and OVA-sensitized murine tissues are shown. Values represent the meantSE of cell numbers/mm2.

Sham-Sham group, mice treated with diluent, during both sensitization and challenge, instead of with OVA. OVA-2w i.n. OVA group, mice in which OVA challenge was given intranasally from day 22 to day 35 after sensitization from day 1 to day 21.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of murine ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized nasal mucosa. (a) Eosinophils (pink-cytoplasm and blue-nucleus stained cells) and basophilic cells (purple-stained cells); scale bar = 25 µm. (b) CD4+ cells (red, stained by streptABC-PO); scale bar = 100 µm. (c) Interleukin (IL)-5+ cells [red, stained by streptavidin–biotin peroxidase detection system (streptABC-PO)]; scale bar = 100 µm. (d) IL-4+ cells (pink, stained by ABC-AP); scale bar = 62·5 µm.

Bone marrow analysis (Table 2)

Table 2.

Bone marrow changes in ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized mice

| OVA-2w i.n. OVA group | OVA-1w i.n. OVA group | OVA-non-i.n. group | Sham-Sham group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sternal bone marrow | ||||

| Eosinophilic cells† | 28·9 ± 5·3(4·5 ± 0·6)* | 63·1 ± 7·3**(8·2 ± 0·5)** | 75·8 ± 11·6**(9·3 ± 2·5) | 15·7 ± 6·7(1·7 ± 0·7) |

| Basophilic cells† | 15·6 ± 2·8(2·3 ± 0·1)* | 27·1 ± 7·0*(3·6 ± 0·9)* | 12·4 ± 2·7(1·8 ± 0·4) | 10·7 ± 1·1(1·1 ± 0·3) |

| CD34+ cells‡ | 73·4 ± 18·2**(5·6 ± 1·5)* | 78·9 ± 12·8**(5·2 ± 0·7)** | 11·1 ± 1·8(1·1 ± 0·2) | 15·8 ± 6·5(1·4 ± 0·5) |

| Femoral bone marrow | ||||

| Eosinophilic cells† | 127·6 ± 48·5*(5·4 ± 1·6)* | 165·8 ± 15·4**(6·1 ± 0·5)** | 242·5 ± 35·5**(6·5 ± 1·0)** | 30·6 ± 7·0(1·1 ± 0·2) |

| Basophilic cells† | 55·8 ± 13·3(2·8 ± 0·7) | 206·7 ± 41·4**(7·5 ± 1·2)** | 79·1 ± 36·1(2·1 ± 0·9) | 51·3 ± 12·6(1·9 ± 0·4) |

| CD34+ cells‡ | 177·1 ± 25·7**(5·4 ± 0·4)** | 237·4 ± 50·8**(4·5 ± 0·4)** | 112·4 ± 30·8(1·8 ± 0·5) | 53·5 ± 19·6(1·3 ± 0·4) |

P < 0·05,

P < 0·01 when compared to the Sham-Sham group.

Number of cells (mean±SE) × 104/sternal bone marrow. Values in parenthesis indicate percentage (mean±SE) compared with total bone marrow cells.

Number of cells (mean±SE) × 103/sternal bone marrow. Values in parenthesis indicate percentage (mean±SE) compared with total bone marrow cells.

OVA-2w i.n. OVA group, mice in which OVA challenge was given intranasally from day 22 to day 35 after sensitization from day 1 to day 21. OVA-1w intranasal (i.n.) OVA group, mice that were challenged with OVA from day 22 to day 28 after sensitization. OVA-non-i.n. group, mice that were given sensitization without OVA challenge. Sham-Sham group, mice treated with diluent, during both sensitization and challenge, instead of with OVA.

In comparisons among the four groups (n = 5 each), a significant increase in bone marrow eosinophilic cell counts was observed after OVA sensitization in both sternal and femoral bone marrow, especially in the OVA-1w i.n. OVA group. The number of basophilic cells in the bone marrow showed a pattern similar to that of eosinophilic cells, and the number of CD34+ cells also increased significantly in the OVA-1w i.n. OVA group and the OVA-2w i.n. OVA group.

Eo/Baso-CFU analysis

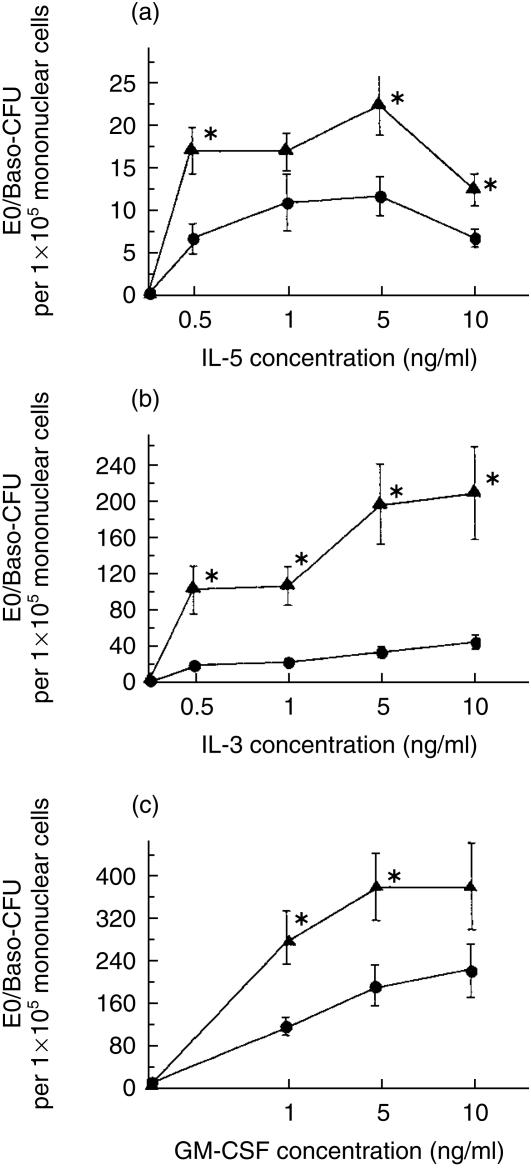

In 6-day methylcellulose-based culture assays, the number of Eo/Baso-CFU increased significantly in the OVA-2w i.n. OVA group in the presence ex vivo of rmIL-5, rmIL-3 or rmGM-CSF (Fig. 5); without cytokines, no CFU growth was observed. In the presence of rmIL-5, cultures of bone marrow-derived NAMNC from OVA-2w i.n. OVA group mice produced significantly greater numbers of Eo/Baso-CFU. In the presence of rmIL-3 or rmGM-CSF, cultures of bone marrow-derived NAMNC from OVA-2w i.n. OVA group mice also produced significantly greater numbers of Eo/Baso-CFU.

Figure 5.

Bone marrow eosinophil/basophil colony-forming units (Eo/Baso-CFU) in murine allergic rhinitis. Dose–response curves of Eo/Baso-CFU growth from bone marrow in ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized (OVA-2w i.n. OVA group, i.e. mice in which OVA challenge was given intranasally from day 22 to day 35 after sensitization from day 1 to day 21) or non-sensitized (Sham-Sham group, i.e. mice treated with diluent, during both sensitization and challenge, instead of with OVA) mice using a range of mouse recombinant cytokines (n = 8 each for each point): (a) Interleukin (IL)-5; (b) IL-3; and (c) granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). The closed circle represents the result from OVA-2w i.n. OVA group and the closed triangle represents that from Sham-Sham group (mean±SE). *P < 0·05 when compared to the Sham-Sham group.

Kinetics of inflammatory changes in the nasal mucosa

As demonstrated in Fig. 6, a 24-hr kinetic study showed that in this experimental design, eosinophil accumulation in the nasal mucosa occurred at 1 hr postchallenge. CD4+ lymphocytes had accumulated by 4 hr after provocation. Basophilic cell counts showed no significant changes during the 24 hr postchallenge (data not shown). In the bone marrow, eosinophilic cell counts tended to decrease 1 hr after provocation; however, this was not significant (P = 0·12). CD34+ cells had increased significantly in number, 4 hr after challenge. Results of femoral bone marrow counts revealed a similar tendency (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Results of a 24-h kinetic study of nasal mucosa and bone marrow. (a) Number of CD4+ cells in nasal mucosa. (b) Number of eosinophils in nasal mucosa. (c) Number of CD34+ cells in sternal bone marrow. (d) Number of eosinophils in sternal bone marrow. Each x-axis depicts certain time-points after ovalbumin (OVA) challenge. Pre, prechallenge. Each y-axis depicts positive cell counts in nasal mucosa or in bone marrow. *P < 0·05 compared with the prechallenge value.

Discussion

To fully understand the pathogenesis of allergic inflammation at a given tissue site, it is useful to study both systemic and local mechanisms contributing to this process. The present study has examined a potentially important aspect of the process of experimental allergic inflammation in the airways: demonstration of activation of a key marker of systemic response – i.e. bone marrow progenitor cell recruitment – during the induction of experimental allergic rhinitis. First, we showed that sensitization by methods employed in this study led to a ‘pure’ allergic rhinitis in mice, as evidenced by isolated upper airway changes symptomatically, pathologically and physiologically, without such changes in the lower airway. In several previous studies in which a murine allergic rhinitis model was established experimentally, the lower airway was not formally examined.11–13 In the present study, nasal symptoms and nasal hyper-responsiveness were observed, and increased significantly during daily i.n. OVA antigen challenge, which paralleled the accumulation of allergic inflammatory cells in the nasal mucosa. Significant increases of OVA-specific IgE in serum were demonstrated in the sensitized groups, in the absence of pathological or physiological changes in the lower airway.

A recent study from our group has described a murine model with significant lower airway eosinophilia and bronchial hyper-responsiveness accompanied with bone marrow eosinophil progenitor increases which are temporally related to lung changes in BALB/c mice after i.p. OVA sensitization and i.n. OVA challenge.1,17 The differences between the latter model and our present upper airway model are described below. First, the i.p. dose of OVA in this current model is lower, and the i.n. dose more frequent and higher than in the lower airway model; compared to the lower airway model of Inman et al.,1 the i.p. dose we used was almost 50-fold lower and divided into four doses; the i.n. dose was fivefold more concentrated and given more frequently (daily for 7–14 days versus twice). Second, antigen distribution after i.n. challenge is different: for the lower airway model, mice were challenged with OVA under general anaesthesia, with aspiration of the OVA solution to the lower airway through the nasal cavity, while in the present model, challenge was performed in non-anaesthetized animals and the antigen did not move to the lower airway, presumably because of an intact pharyngeal reflex (as shown by the Trypan Blue dye study), although this could be examined by more sensitive methods such as an application and detection of radioisotope-labelled OVA solution to mice in future studies. Therefore, the upper airway allergic inflammatory changes appear not only to be a reflection simply, by contiguity, of lower airway changes, but also represent an independent organ reaction, at least in this murine experimental model. How antigen presentation, in the context of a systemic response, can induce inflammation in the upper, but not the lower, airway, remains to be determined.

In the present murine experimental ‘pure’ allergic rhinitis, the numbers of mature and immature eosinophilic and basophilic cells in the bone marrow increased significantly during OVA sensitization. Bone marrow participation in various allergic disorders has already been described18 in several studies in human subjects that examined the relationship between peripheral blood and/or bone marrow progenitors and the development of upper and lower airway inflammation.3–10,19,20 The current study formally demonstrates, for the first time, the activation of bone marrow inflammatory cells and their progenitors in a situation in which an isolated upper airway response is generated, in contrast to our human studies3–7 in which allergic inflammation may well have been occurring at several sites (nose, lung, skin) simultaneously. High levels of bone marrow eosinophilic cells were seen (particularly after i.p. OVA sensitization), which then decreased following ongoing challenge and was accompanied with the development of tissue eosinophilia. Such responses have been previously documented, with or without anti-IL-5 treatment, in an OVA-immunized murine model,2,19,21 and could be explained by chemotaxis of mature eosinophils to tissues, from the bone marrow pool, under the influence of IL-52 and eotaxin.22 In addition, there was a different pattern between sternal and femoral bone marrow responses, as shown in Table 2. This could be explained by differences in group sizes; further investigations with adequate numbers for statistical analysis are required.

We have also studied CD34+ progenitor cells in murine bone marrow during airway allergen challenge, showing that these cells are maintained at high levels in the bone marrow during the daily antigen challenge protocol. This is in accordance with our previous finding of higher than normal levels of CD34+ cells in cross-sectional studies of blood and marrow in atopic (asthmatic/allergic and rhinitic) individuals;7 there is also a previous study on OVA-immunized mice in which significantly increased numbers of bone marrow cells were found to yield eosinophil-bearing colonies and differentiated eosinophhils after 7 days of liquid culture in the presence of IL-5 or IL-3.2 Therefore, to determine whether such a significant bone marrow change occurs in the isolated allergic rhinitis model, bone marrow culture studies were performed and the proliferation of Eo/Baso-CFU in bone marrow was evaluated as a measure of marrow function, i.e. the capacity to produce and deliver inflammatory cells to tissues. In the presence of mouse recombinant IL-5, IL-3 or GM-CSF, the number of bone marrow Eo/Baso-CFU increased significantly in the OVA-sensitized group. Therefore, in the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis, the bone marrow appears to be activated functionally to respond to cytokine signals, which leads to the production of allergic inflammatory cells, similarly to that shown in lower airway allergic inflammation.1

The kinetics of cellular responses during the first 24 hr after OVA i.n. challenge demonstrate a peak eosinophil accumulation at 1 hr after i.n. provocation, at a time when eosinophil numbers in the bone marrow are decreasing. This suggests an active recruitment of mature eosinophils from the bone marrow to the nasal mucosa during the effector phase of the immune response to OVA.21,22 Interestingly, nasal mucosal CD4+ lymphocytes accumulated later than eosinophils, while CD34+ cells in the bone marrow increased to a peak at 4 hr postchallenge. This temporal sequence is compatible with bone marrow involvement, even during the induction phase of allergic rhinitis.

Whether specific signals such as IL-5, GM-CSF or other haemopoietins derived from upper or lower airway tissues can induce these bone marrow changes in progenitors and mature cells, has recently been explored in both human and canine models of lower airway hyper-responsiveness,7,9,23,24 but a clear answer is not yet available. Recent studies suggest that locally active bone marrow IL-5+ T cells may play a role in progenitor recruitment.25

Whether the co-occurrence of asthma and allergic rhinitis in humans is attributable to a systemic contribution from the bone marrow, or is simply a reflection of postnasal drip, neural reflex, or other local mechanisms,26–36 has not yet been fully resolved. Our current ‘pure’ allergic rhinitis model might be useful in investigating the role of the bone marrow in airway interactions.

In conclusion, there are both local and systemic events initiated in response to allergen provocation, which appear to be required for the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis. Understanding these events and their regulation could provide new therapeutic targets for rhinitis and asthma.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lynne Larocque for her help with the artwork and text. This study was supported by the MRC Canada. Dr Saito is a recipient of an MRC/CTS/AstraZeneca Fellowship Award.

Abbreviations

- AEC

aminoethylcarbazole

- Eo/Baso-CFU

eosinophil/basophil colony-forming units

- GMA

glycolmethacrylate

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- IL

interleukin

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- NAMNC

non-adherent mononuclear cells

- NHR

nasal hyper-responsiveness

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PCA

passive cutaneous anaphylaxis

- rm

recombinant murine

- RRS

total pulmonary resistance

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline.

References

- 1.Inman MD, Ellis R, Wattie J, Denburg JA, O'Byrne PM. Allergen-induced increase in airway responsiveness, airway eosinophilia and bone-marrow eosinophil progenitors in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:473–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.4.3622. PM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaspar Elsas MI, Joseph D, Elsas PX, Vargaftig BB. Rapid increase in bone marrow eosinphil production and responses to eosinopoietic interleukins triggered by intranasal allergen challenge. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:404–13. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.4.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denburg JA, Telizyn S, Belda A, Dolovich J, Bienenstock J. Increased numbers of circulating basophil progenitors in atopic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985;76:466–72. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(85)90728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otsuka H, Dolovich J, Befus AD, Telizyn S, Bienenstock J, Denburg JA. Basophilic cell progenitors, nasal metachromatic cells, and peripheral blood basophils in ragweed-allergic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78:365–71. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(86)80091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson PG, Dolovich J, Girgis-Gabardo A, Morris MM, Anderson M, Hargreave FE, Denburg JA. The inflammatory response in asthma exacerbation: changes in circulating eosinophils, basophils and their progenitors. Clin Exp Allergy. 1990;20:661–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1990.tb02705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson PG, Manning PJ, O'Byrne PM, Girgis-Gabardo A, Dolovich J, Denburg JA, Hargreave FE. Allergen-induced asthmatic responses: relationship between increases in airway responsiveness and increases in circulating eosinophils, basophils, and their progenitors. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:331–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sehmi R, Howie K, Sutherland DR, Schragge W, O'Byrne PM, Denburg JA. Increased levels of CD34+ hemopoietic progenitor cells in atopic subjects. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:645–54. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.5.8918371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolley MJ, Denburg JA, Ellis R, Dahlback M, O'Byrne PM. Allergen-induced changes in bone marrow progenitors and airway responsiveness in dogs and the effect of inhaled budesonide on these parameters. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:600–6. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.5.7946389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inman MD, Denburg JA, Ellis R, Dahlback M, O'Byrne PM. Allergen-induced increase in bone marrow progenitors in airway hyperresponsive dogs: regulation by a serum hemopoietic factor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:305–11. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.3.8924277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denburg JA, Inman MD, Wood L, Ellis R, Sehmi R, Dahlback M, O'Byrne P. Bone marrow progenitors in allergic airways diseases: studies in canine and human models. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;113:181–3. doi: 10.1159/000237540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito H, Asakura K, Watanabe M, Ogasawara H, Kataura A. Investigation of the in vivo effect of cyclosporin A (CsA) on nasal mucosa of egg-albumin sensitized mice. Jpn Soc Immunol Allergol Otolaryngol. 1996;12:154–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asakura K, Saito H, Watanabe M, Ogasawara H, Matsui T, Kataura A. Effects of anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody on the murine model of nasal allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998;116:49–52. doi: 10.1159/000023924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogasawara H, Asakura K, Saito H, Kataura A. Role of CD4-positive T cells in the pathogenesis of nasal allergy in the murine model. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;118:37–43. doi: 10.1159/000024029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levitt RC, Eleff SM, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR, Ewart SL. Linkage homology for bronchial hyperresponsiveness between DNA markers on human chromosome 5q31-q33 and mouse chromosome 13. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25(Suppl. 2):61–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1995.tb00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Britten KM, Howarth PH, Roche WR. Immunohistochemistry on resin sections: a comparison of resin embedding techniques for small mucosal biopsies. Biotech Histochem. 1993;68:271–80. doi: 10.3109/10520299309105629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mancino D, Bevilacqua N. Persistent and boosterable IgE antibody production in mice injected with low doses of ovalbumin and silica. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1978;57:155–8. doi: 10.1159/000232096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster PS. Allergic networks regulating eosinophilia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:451–4. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.4.f167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mygind N, Dahl R, Pedersen S, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Essential Allergy. 2. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohkawara Y, Lei XF, Stampfli MR, Marshall JS, Xing Z, Jordana M. Cytokine and eosinophil responses in the lung, peripheral blood, and bone marrow compartments in a murine model of allergen-induced airways inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:510–20. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.5.9160833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki A, Andrew DP, Gonzalo JA, et al. CD34-deficient mice have reduced eosinophil accumulation after allergen exposure and show a novel crossreactive 90-kD protein. Blood. 1996;87:3550–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egan RW, Athwahl D, Chou CC, et al. Pulmonary biology of anti-interleukin 5 antibodies. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92(Suppl. 2):69–73. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000800011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conroy DM, Humbles AA, Rankin SM, Palframan RT, Collins PD, Griffiths-Johnson DA, Jose PJ, Williams TJ. The role of the eosinophil-selective chemokine, eotaxin, in allergic and non-allergic airways inflammation. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92(Suppl. 2):183–91. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000800024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood LJ, Inman MD, Watson RM, Foley R, Denburg JA, O'Byrne PM. Changes in bone marrow inflammatory cell progenitors after inhaled allergen in asthmatic subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:99–105. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9704125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood LJ, Inman MD, Denburg JA, O'Byrne PM. Allergen challenge increases cell traffic between bone marrow and lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;18:759–67. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.6.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minshall EM, Schleimer R, Cameron L, Minnicozzi M, Egan RW, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q. Interleukin-5 expression in the bone marrow of sensitized BALB/c mice after allergen challenge. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:951–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9709114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pratter MR, Bartter T, Lotano R. The role of sinus imaging in the treatment of chronic cough in adults. Chest. 1999;116:1287–91. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchesani F, Cecarini L, Pela R, Sanguinetti CM. Causes of chronic persistent cough in adult patients: the results of a systematic management protocol. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1998;53:510–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lalloo UG, Barnes PJ, Chung KF. Pathophysiology and clinical presentations of cough. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:S91–S97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aaronson DW. Evaluation of cetirizine in patients with allergic rhinitis and perennial asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1996;76:440–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63461-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen KL, Corbett ML, Garcia DP, et al. Chronic sinusitis among pediatric patients with chronic respiratory complaints. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:824–30. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90059-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corren J. Allergic rhinitis and asthma: how important is the link? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:S781–6. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mygind N, Dahl R, Nielsen LP. Effect of nasal inflammation and of intranasal anti-inflammatory treatment on bronchial asthma. Respir Med. 1998;92:547–9. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dahl R, Mygind N. Mechanisms of airflow limitation in the nose and lungs. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28(Suppl. 2):17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corren J, Adinoff AD, Irvin CG. Changes in bronchial responsiveness following nasal provocation with allergen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;89:611–8. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90329-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aubier M, Levy J, Clerici C, Neukirch F, Herman D. Different effects of nasal and bronchial glucocorticosteroid administration on bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with allergic rhinitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:122–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brugman SM, Larsen GL, Henson PM, Honor J, Irvin CG. Increased lower airways responsiveness associated with sinusitis in a rabbit model. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:314–20. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]