Abstract

We evaluated the use of recombinant human interleukin-6 (rhIL-6) and a monoclonal antibody specific for interferon-γ (IFN-γ) as co-adjuvants in a subunit vaccine against tuberculosis consisting of the culture filtrate proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (ST-CF) emulsified in the adjuvant dimethyl-dioctadecylammonium bromide (DDA). Both the addition of rhIL-6 and the neutralization of IFN-γ resulted in an increased T helper type 1 (Th1) response characterized by enhanced IFN-γ production and cell proliferation. Nevertheless, this did not result in the enhancement of protection against either an intravenous or an aerosol M. tuberculosis challenge. Our data stress the need to identify further correlates of protection in addition to IFN-γ production to screen vaccines against tuberculosis infection.

Introduction

Resistance of mice to mycobacteria in general and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in particular depends on the ability of the host to produce interferon-γ (IFN-γ).1–3 In the human, the disruption of the cytokine axis leading to the secretion of IFN-γ, namely due to mutations in the genes encoding the IFN-γ receptor and interleukin-12 (IL-12), predispose for mycobacterial infections.3 Therefore, a correlate of protection currently used to evaluate the efficacy of anti-tuberculosis vaccines has been the level of IFN-γ production following in vitro stimulation of immune cells. There has generally been an agreement between the magnitude of the Th1 response induced by experimental vaccines and the protection they promote.4

In a simplistic way, potentiating the IFN-γ response would be a way to promote the efficacy of a tuberculosis vaccine. Thus we have been attempting to determine which cytokines are involved in the induction of IFN-γ production by a tuberculosis subunit vaccine using distinct immunomodulatory strategies, in order to try to improve the protection afforded by such a vaccine. In a previous report5 we have shown that the endogenous production of both IL-6 and IL-12 are required for the induction of an IFN-γ-dominated response to the aforementioned vaccine. It has also been shown that the co-administration of IL-12 together with mycobacterial subunit vaccines is able to potentiate the IFN-γ-generating capacity of immune cells5 as well as their protective efficacy.5–7 On the other hand, the inclusion of IL-6 in the first immunization could reverse the lack of IFN-γ priming observed in IL-6-deficient mice. Preliminary analysis of the effects of cytokine depletion during vaccination also showed that neutralization of IFN-γ would lead to a paradoxical enhanced response with increased production of IFN-γ itself. We confirm here that the neutralization of IFN-γ and the administration of IL-6 lead to enhanced IFN-γ responses to the tuberculosis protein subunit vaccine. Nevertheless, we have failed to observe a correlation between the enhancement of the IFN-γ response to the vaccine antigens and a concomitant increase in protection, highlighting the need to establish other correlates of protection to the evaluation of anti-tuberculosis vaccines.

Materials and methods

Animals and immunizations

C57BL/6 female mice (8–10-week-old, purchased from the Gulbenkian Institute in Oeiras, Portugal or from Bomholtegård in Ry, Denmark) were subcutaneously (s.c.) immunized twice with a 2-week interval, or three times at weekly intervals, at the dorsal base of the tail with a vaccine consisting of a mixture of 50 µg of short-term culture filtrate (ST-CF) proteins from M. tuberculosis8 and 250 µg of the adjuvant dimethyl-dioctadecylammonium bromide (DDA) (Eastman Kodak Inc., Rochester, NY) as described previously.5 In some experiments, recombinant human IL-6 (rhIL-6, Ares-Serono, Geneva, Switzerland) was added directly to the mixture of ST-CF and DDA on the day of the first immunization and injected alone on the following days. In other experiments, a monoclonal antibody specific for IFN-γ [a rat immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) secreted by the hybridoma XMG1.2, DNAX, Palo Alto, CA] or a control antibody (either the anti-β-galatosidase GL113 monoclonal antibody or non-immune rat immunoglobulin) were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 2–3 hr before the vaccine at a dose of 2 mg per animal.

In vitro assays

Spleen cells were isolated 3 weeks after the last immunization and were prepared as described previously.5 They were stimulated in vitro with 4 µg of ST-CF per ml and lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ secretion were analysed as described.5 IL-5 secretion was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay by using the antibody pairs specific for IL-5 secreted by hybridoma cell line TRFK-5 (DNAX, Palo Alto, CA) as coating antibody and by TRFK-4 (DNAX) as a detecting antibody. The standards were made of recombinant IL-5 from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). The sensitivity of the assay was such that it could detect 10 pg of the cytokine per ml.

Assessment of protective immunity

To assess the generation of protective immunity to tuberculosis, groups of five mice were immunized s.c. with either 5 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU) of bacille Calmette–Guèrin (BCG, Danish strain 1331) or with three weekly doses of the ST-CF plus DDA vaccine given as such or modified with either rhIL-6 (30 µg admixed with the vaccine in the first immunization, and two similar doses on the two subsequent days by s.c. injection) or with anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (2 mg of antibody given with the first and third immunizations and 2 weeks after the last immunization). Mice were infected either intravenously (i.v.) with 5 × 104 CFU of M. tuberculosis Erdman 5 weeks after the last immunization or aerogenically by exposure to an aerosol challenge with 5 × 106 CFU of M. tuberculosis Erdman per ml, leading to a pulmonary seeding with 15–20 CFU, 6 weeks after the last immunization. Mice were killed 2 weeks after the i.v. challenge or 6 weeks after the aerosol infection and the organs were removed for bacterial enumeration. The values are presented as log10 resistance corresponding to the difference between the log10CFU in control (non-immune) mice and the log10CFU in the immunized groups.

Results

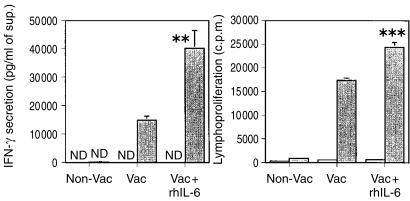

Previous studies in our laboratory showed that administration of IL-6 at the early stages of immunization boosts the priming of antigen-specific T cells for IFN-γ secretion. C57BL/6 mice were immunized twice with ST-CF and DDA and half of the animals received recombinant IL-6 with the first dose of the vaccine and in the following 2 days. Spleen cells were collected 3 weeks after the second immunization and were specifically stimulated in vitro. As shown in Fig. 1, the injection of IL-6 during the first immunization with ST-CF and DDA led to a statistically significant increase in IFN-γ production and in cell proliferation as compared to vaccinated mice that did not receive the cytokine.

Figure 1.

Effects of the early addition of rhIL-6 in the priming of T cells during the immunization of C57BL/6 with ST-CF in DDA. C57BL/6 mice were immunized twice with the ST-CF/DDA vaccine (Vac) or injected with PBS/DDA (Non-Vac) at 2-week interval. Recombinant human IL-6 (30 µg per dose) was administered with the first immunization and in the two subsequent days by subcutaneous injection. Mouse spleens (three per group) were collected 3 weeks after the last immunization and the cells were pooled and cultured in triplicate wells, in vitro, with (shaded bars) or without (white bars) ST-CF (4 µg/ml). The amount of IFN-γ secreted as well as lymphoproliferation were evaluated (at 96 or 48 hr, respectively) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and radioactive thymidine incorporation, respectively. (ND, not detectable). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test (**P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001). The statistical analysis between the vaccinated group and the vaccinated group treated with IL-6 are shown.

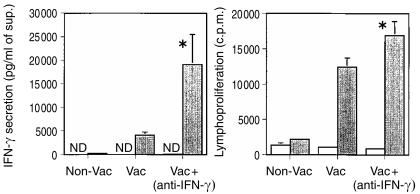

During a screening of the effects of specific cytokine neutralization during vaccination we found that neutralizing IFN-γ had the counter-intuitive effect of enhancing the priming of T cells for IFN-γ release. We show here a typical experiment demonstrating that the neutralization of IFN-γ with a specific monoclonal antibody during the immunization significantly increased IFN-γ secretion and lymphoproliferation as compared to immunized mice receiving a control antibody (Fig. 2). These findings were confirmed in three independent experiments. Furthermore, only vestigial amounts of IL-5 were found in the supernatants of the two groups (data not shown) and the treatment with the anti-IFN-γ antibody did not switch the immunonoglobulin isotype response following vaccination, since no changes in the IgG2a to IgG1 ratio were found between the control immunized and the treated groups (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of the neutralization of IFN-γ in the priming of T cells during the immunization of C57BL/6 with ST-CF in DDA. C57BL/6 mice were immunized subcutaneously, three times at weekly intervals with ST-CF/DDA (50 µg and 250 µg, respectively, in 0·2 ml) (Vac) or with PBS/DDA (Non-Vac) and a monoclonal antibody specific for IFN-γ (anti-IFN-γ) or an irrelevant immunoglobulin preparation was administered 2 hr before the first and third immunizations, by i.p. injection (2 mg/animal). Mouse spleens (three per group) were collected 3 weeks after the last immunization and the cells were pooled and cultured in triplicate wells, in vitro, with (shaded bars) or without (white bars) ST-CF (4 µg/ml). The amount of IFN-γ secreted as well as lymphoproliferation were evaluated (at 96 or 48 hr, respectively) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and radioactive thymidine incorporation, respectively. (ND, not detectable). Statistically significant effects of the antibody treatment are indicated by * (for P < 0·05), according to Student's t-test. The statistical analysis between the vaccinated group and the vaccinated group treated with anti-IFN-γ are shown.

To assess whether these treatments that enhanced the priming of the IFN-γ responses had an impact on the generation of protective immunity to tuberculosis, mice were immunized with either BCG as a positive control group or with the ST-CF plus DDA vaccine given as such or modified with either rhIL-6 or with anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody. Mice were challenged by either the i.v. route or aerogenically 5 weeks after the last immunization. In order to reduce the non-specific protection induced by vaccination and related to inflammatory reactions to the preparations, the time interval from immunization to challenge was longer than that in the previous experiments. However, in vitro stimulation of the lymph node cells of immunized mice at the time of challenge showed that the memory recall response was similar to that at 3 weeks post-vaccination and that the immunomodulatory treatments had the same IFN-γ-promoting effects (not shown). Protection was assessed at the peak of mycobacterial proliferation,9,10 i.e. at 2 weeks in the i.v. challenge and at 6 weeks in the aerosol challenge by comparing mycobacterial loads in non-immune versus the immunized mice at those time-points. Although the addition of rhIL-6 to the vaccine and the neutralization of IFN-γ conferred a higher capacity for IFN-γ priming to the vaccine, neither treatment was able to increase its protective efficacy either upon an aerosol (Fig. 3a) or an intravenous challenge (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Effect of the early addition of rhIL-6 or IFN-γ neutralization on the protection conferred by the ST-CF/DDA vaccine to an aerosol or an i.v. challenge with M. tuberculosis. Groups of five C57Bl/6 mice were immunized s.c. with ST-CF/DDA (Vac) three times at weekly intervals or injected with PBS/DDA. Recombinant human IL-6 (30 µg/animal) or phosphate-buffered saline alone were administered with the first immunization and on the two subsequent days by s.c. injection. A monoclonal antibody specific for IFN-γ (anti-IFN-γ) or an irrelevant immunoglobulin preparation were administered 2 hr before the first and third immunizations, and 2 weeks after the last immunization, by i.p. injection (2 mg/animal). Another group was immunized with 5 × 104 CFU of BCG per animal while its control group was left untreated. Thirty-five days after the last immunization mice were challenged with M. tuberculosis Erdman either through an aerosol infection (15–20 CFU per lung) (a) or intravenously (i.v.) (5 × 104 CFU per animal) (b) Bacterial organ count was determined 14 and 42 days after the i.v. and aerosol challenge, respectively. Results are represented as log10 of resistance, which was calculated by subtracting the mean of log10CFU in the immune groups from the mean of log10CFU in the control, non-immune group. Statistical analysis was done by comparing the immune groups with the immune groups treated as indicated using Student's t-test (NS, P > 0·05).

Discussion

We had previously seen that the neutralization of IL-6 during the vaccination process with ST-CF in DDA decreased IFN-γ priming to very low levels and that it also reduced cell proliferation.5 Moreover, we had shown that the need for IL-6 was essentially restricted to the induction phase of the immune response to this subunit vaccine.5,11 Here we demonstrate that the use of rhIL-6 as a co-adjuvant to the vaccine, in the days that follow the first immunization, is also capable of increasing IFN-γ production in wild-type animals. This confirms the role of IL-6 in the induction of a Th1 response to the vaccine. The need for IL-6 at the beginning of the immune response against a M. tuberculosis infection has also recently been demonstrated by Saunders et al.12 More surprising was the fact that neutralization of IFN-γ during immunization led to an enhancement of the priming of T cells for the secretion of IFN-γ itself. However, IFN-γ may have a role in the induction of apoptosis of T cells,13–17 namely in down-regulating the number of responding CD4 T cells during a mycobacterial infection by inducing apoptosis of the activated CD4 T cells.13 Thus, the neutralization of IFN-γ could be preventing the programmed cell death of stimulated CD4 T cells specific for the mycobacterial antigens, thereby leading to an increase in the number of IFN-γ producing cells. Also, this could explain the observed increase in cell proliferation. Experiments are under way to examine the mechanisms underlying the effect of IFN-γ neutralization.

The in vitro stimulation of immune cells with antigen and the measure of IFN-γ secretion in the culture supernatants is a routine assay to assess the efficacy of vaccination protocols. The production of IFN-γ is generally taken as a correlate of protection and used to screen vaccine strategies. However, we showed here that despite increasing IFN-γ production, the early administration of rhIL-6 or the neutralization of IFN-γ were unable to improve the protective efficacy of the subunit vaccine. Although the general tendency seems to be that efficient tuberculosis subunit vaccines induce IFN-γ,4 an enhanced priming of T cells for IFN-γ production does not always imply an increase in protection against M. tuberculosis such as in the case of DNA vaccines encoding M. tuberculosis antigens18–20 and recombinant vaccines expressing M. tuberculosis antigens.21 A possible explanation for our results is that the vaccine already induces an optimal amount of IFN-γ needed for protection and that the increase in production of this cytokine induced by rhIL-6 or the administration of the anti-IFN-γ antibody is superfluous. This explanation is highly relevant as the vaccine efficacy of the DDA-adjuvanted vaccine, at least in the lung, is at the same level as BCG. The mouse model may therefore not allow the detection of an improvement and the discrimination between different vaccines at the top end of the scale. In the future it would therefore be highly relevant to test such a strategy in other animal models or even the improvement of more suboptimal vaccines (e.g. with a less efficient adjuvant) in the mouse model. Alternatively, the treatments that affected IFN-γ production might have failed to increase additional effector pathways required for protection against tuberculosis infection, as even in the presence of IFN-γ other components of the immune system need to be present. These might include tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα), essential for granuloma formation, Fas ligand, which may allow the release of live mycobacteria from macrophages unable to kill them, or granulysin, a molecule secreted by CD8+ T cells that is able to directly kill mycobacteria (for reviews see refs 22 and 23) as well as other as yet unknown protective factors. In this context, we have recently shown that IFN-γ-independent pathways may be required for the effective control of M. avium replication.24,25 Similar data are emerging from other laboratories.26,27 This issue is of particular relevance in the study of new vaccines as screening for immune correlates of protection is far more cost-effective and less labour-consuming than the actual study of protective efficacy with infection models. Our data show that using IFN-γ as the only read-out in such screenings may be misleading, as already discussed by others.28

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Commission of the European Communities STD3 programme (contract TS3*-CT/94-0313) and the INCO/DC programme (contract no. ERBIC18CT970254). I.S.L. received a fellowship from the PRAXIS XXI programme (Lisbon).

References

- 1.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. An essential role for interferon γ in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jouanguy E, Döffinger R, Dupuis S, Pallier A, Altare F, Casanova J-L. IL-12 and IFN-γ in host defense against mycobacteria and salmonella in mice and men. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:346–51. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80055-7. 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agger EM, Andersen P. Tuberculosis subunit vaccine development: on the role of interferon-γ. Vaccine. 2001:2298–302. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00519-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leal IS, Smedegård B, Andersen P, Appelberg R. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-12 participate in induction of a type 1 protective T-cell response during vaccination with a tuberculosis subunit vaccine. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5747–54. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5747-5754.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin SL, D'Souza C, Roberts AD, et al. Evaluation of new vaccines in the mouse and guinea pig model of tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2951–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2951-2959.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva RA, Pais TF, Appelberg R. Evaluation of IL-12 in immunotherapy and vaccine design in experimental Mycobacterium avium infections. J Immunol. 1998;161:5578–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen P, Askgaard D, Ljungqvist L, Bennedsen J, Heron I. Proteins released from Mycobacterium tuberculosis during growth. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1905–10. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.1905-1910.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orme IM, Collins FM. Mouse model of tuberculosis. In: Bloom BR,, editor. Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Protection, and Control. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 113–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orme IM. The kinetics of emergence and loss of mediator T lymphocytes acquired in response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1987;138:293–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leal IS, Flórido M, Andersen P, Appelberg R. IL6 regulates the phenotype of the immune response to a tuberculosis sub-unit vaccine. Immunology. 2001:375–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saunders BM, Frank AA, Orme IM, Cooper AM. Interleukin-6 induces early gamma interferon production in the infected lung but is not required for generation of specific immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3322–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3322-3326.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu C-Q, Wittmer S, Dalton DK. Failure to suppress the expansion of the activated CD4 T cell population in interferon γ-deficient mice leads to exacerbation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:123–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalton DK, Haynes L, Chu C-Q, Swain SL, Wittmer S. Interferon γ eliminates responding CD4 T cells during mycobacterial infection by inducing apoptosis of activated CD4 T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:117–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liesenfeld O, Kosek JC, Suzuki Y. Gamma interferon induces Fas-dependent apoptosis of Peyer's patch T cells in mice following peroral infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4682–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4682-4689.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Janeway CA. Interferon γ plays a critical role in induced cell death of effector T cell: a possible third mechanism of self-tolerance. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1735–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins GA, Vieira LQ, Cunha FQ, Silva JS. Gamma interferon modulates CD95 (Fas) and CD95 ligand (Fas-L) expression and nitric oxide induced apoptosis during the acute phase of Trypanosoma cruzi infection: a possible role in immune response control. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3864–71. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3864-3871.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z, Howard A, Kelley C, Delogu G, Collins F, Morris S. Immunogenicity of DNA vaccines expressing tuberculosis proteins fused to tissue plasminogen activator signal sequences. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4780–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4780-4786.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris S, Kelley C, Howard A, Li Z, Collins F. The immunogenicity of single and combination DNA vaccines against tuberculosis. Vaccine. 2000;18:2155–63. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeremeev VV, Lyadova YV, Nikonenko BV, Apt AS, Abou-Zeid C, Inwald J. The 19-KD antigen and protective immunity in a murine model of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;120:274–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01212.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abou-Zeid C, Gares M-P, Inwald J, et al. Induction of a type 1 immune response to a recombinant antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis expressed in Mycobacterium vaccae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1856–62. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1856-1862.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray PJ. Defining the requirements for immunological control of mycobacterial infections. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:366–72. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flynn JL, Ernst JD. Immune responses in tuberculosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:432–6. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appelberg R, Leal IS, Pais TF, Pedrosa J, Flòrido M. Differences in resistance of C57Bl/6 and C57Bl/10 mice to infection by Mycobacterium avium are independent of gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 2000;68:19–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.19-23.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flòrido M, Gonçalves AS, Silva RA, Ehlers S, Cooper AM, Appelberg R. Resistance of virulent Mycobacterium avium to gamma interferon-mediated antimicrobial activity suggests additional signals for induction of mycobacteriostasis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3610–18. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3610-3618.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nau GJ, Liaw L, Chupp GL, Berman JS, Hogan BLM, Young RA. Attenuated host resistance against Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection in mice lacking osteopontin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4223–30. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4223-4230.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scanga CA, Mohan VP, Yu K, Joseph H, Tanaka K, Chan J, Flynn JL. Depletion of CD4+ T cells causes reactivation of murine persistent tuberculosis despite continued expression of interferon γ and nitric oxide synthase 2. J Exp Med. 2000;192:347–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellner JJ, Hirsch CS, Whalen CC. Correlates of protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in humans. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl. 3):S279–82. doi: 10.1086/313874. 10.1086/313874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]