Abstract

A murine model of oral candidiasis was used to show that nitric oxide (NO) is involved in host resistance to infection with Candida albicans in infection-‘resistant’ BALB/c and infection-‘prone’ DBA/2 mice. Following infection, increased NO production was detected in saliva. Postinfection samples of saliva inhibited the growth of yeast in vitro. Treatment with NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (MMLA), an inhibitor of NO synthesis, led to reduced NO production, which correlated with an increase in C. albicans growth. Reduction in NO production following MMLA treatment correlated with an abrogation of interleukin-4 (IL-4), but not interferon-γ (IFN-γ), mRNA gene expression in regional lymph node cells. Down-regulation of IL-4 production was accompanied with an increase in IFN-γ production in infection-‘prone’ DBA/2 mice. There was a functional relationship between IL-4 and NO production in that mice treated with anti-IL-4 monoclonal antibody showed a marked inhibition of NO production in saliva and in culture of cervical lymph node cells stimulated with C. albicans antigen. The results support previous conclusions that IL-4 is associated with resistance to oral candidiasis and suggest that NO is involved in controlling colonization of the oral mucosal surface with C. albicans.

Introduction

Candida albicans, a yeast-like opportunistic fungus, is part of the normal flora that colonizes human mucosal surfaces of the mouth, vagina and gastrointestinal tract. It can cause stomatitis and vaginitis. In immunocompromised hosts it can invade tissues and cause systemic infection.1–4 Cell-mediated immunity plays an important role in the resistance to mucosal candidiasis, but little is known about the mechanisms that protect mucosal surfaces against disease. While macrophages kill micro-organisms using oxygen-dependent and -independent mechanisms,5–7 recent studies in mice have shown that nitric oxide (NO) produced by macrophages contributes to resistance to infection with C. albicans.8,9 For example, inhibition of NO synthesis in vivo leads to increased susceptibility of mice to systemic and mucosal candidiasis8,10 and reduced candidacidal activity of macrophages.8,9 In vitro studies have shown that NO inhibits the growth of C. albicans and is associated with macrophage candidacidal activity.11 We have shown in a murine model of oral candidiasis that host protection is linked to a particular pattern of cytokines and an increase in the number of γ/δ T cells in the regional lymph node.12 The differences in the colonization patterns of C. albicans in ‘infection-resistant’ BALB/c mice and ‘infection-prone’ DBA/2 mice following infection correlated with both T-cell proliferation and the secretion pattern of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-12 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). The results showed that a balanced T helper 1 (Th1) and T helper 2 (Th2) cell response, characterized by secretion of both IL-4 and IFN-γ, correlates with resistance to infection with C. albicans.12 NO influences the Th1/Th2 balance by inhibiting the proliferation of Th1 cells and IFN-γ production13,14 and enhancing IL-4 expression. NO thus favours the generation of Th2 cells.15,16 The aim of this study was to determine the extent to which NO is involved with the resistance in mice to oral candidiasis by examining the effect of NO on the growth of C. albicans and the production of IL-4 and IFN-γ in the regional lymph nodes of mice.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male BALB/c (H2d) and DBA/2 mice (H2d), 6–8 weeks old, were purchased from the Animal Resource Center (Perth, Western Australia). They were housed in groups of three to five and provided with food and water ad libitum. All mice were used after 1 week of acclimatization.

Fungal culture

C. albicans isolate 3630 was obtained from the National Reference Laboratory (Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia). The yeast cells were cultured in Sabouraud dextrose broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) for 48 hr at 25° in a shaking water bath. The blastospores were transferred into fresh medium and cultured at 25° for a further 18 hr. Then, the blastospores were collected by centrifugation, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and adjusted to 108 blastospores/ml in PBS until use.

C.albicans antigen

Freshly cultured organisms of C. albicans isolate 3630 were resuspended in PBS at 1010 cells/ml and then sonicated in an MSE Soniprep (MSE Ltd, Crawley, UK) set at an amplitude of 10 for 30 cycles with intermittent cooling and sonication. The sonicate was centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 g, after which the supernatant was collected and dialysed against PBS. After protein estimation, the solution was filtered and stored in aliquots at −20° until use.

Oral infection

Mice were inoculated orally with C. albicans, according to the method described by Chakir et al.17 Briefly, 108 blastospores/ml in PBS were centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min. The pellet was recovered on a fine-tip sterile swab (MW & E, Corsham, UK), which was then used for oral inoculation by topical application.

Quantification of oral infection

Groups of mice (five per group) were killed at various time-points to determine the number of C. albicans in the oral mucosa. The oral cavity (i.e. cheek, tongue and soft palate) was swabbed with using a fine-tip cotton swab. After swabbing, the cotton end was cut off and placed in an Eppendorf tube containing 1 ml of PBS. The yeast cells were resuspended by mixing on a vortex mixer before culture in serial 10-fold dilutions on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Oxoid) supplemented with chloramphenicol (0·05 g/l), for 48 hr at 37°. The results were expressed as log 10 colony-forming units (CFU) per mouse.

Cytokine assay

The cervical lymph nodes (CLN) were excised from five C. albicans-infected mice at each time-point after infection.12 Pooled CLN cells in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) were cultured at 4 × 106 cells/well in the presence of 2·5 µg/ml of C. albicans antigen in wells of a 24-well plate for 3 days, as described above. The culture supernatants were collected and then assayed for IL-4 and IFN-γ by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using matched-antibody pairs and recombinant cytokines as standards (PharMingen, San Diego, CA).12 Briefly, immuno-polysorb microtitre plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with capture rat monoclonal anti-IL-4 (αIL-4) (IgG1) or IFN-γ (IgG1) antibody at 1 µg/ml in sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 9·6) overnight at 4°. The wells were washed and then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) before the culture supernatants and the appropriate standard were added to each well. Biotinylated rat monoclonal anti-IL-4 and IFN-γ antibody at 2 µg/ml was added as second antibody. Detection was carried out using streptavidin peroxidase (Amrad, Melbourne, Australia) and tetramethyl benzedine (TMB) (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA). The sensitivities of the cytokine ELISAs were 31 pg/ml and 15 pg/ml for IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)

RNA extraction and amplification of synthesized cDNA from lymphoid cells have been described previously.18,19 Briefly, 10 µl of total RNA extracted from 4 × 106 CLN cells/ml was added to 20 µl of RT mix containing 6 µl of 5× RT reaction buffer (250 mm Tris–HCl, 375 mm KCl, 15 mm MgCl2), 3 µl of 100 mm dithiothreitol, 1·5 µl of deoxynucleotide (10 mm), 1 µl of RNAse inhibitor (40 U/ml), 0·5 µl of Moloney murine leukaemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase (200 U/ml), 3 µl of oligo-(dT)15′, 3 µl of acetylated BSA (1 mg/ml) and 2 µl of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. The cDNA synthesis was carried out at 42° for 1 hr followed by heating at 72° for 10 min. PCR amplification was carried out by adding 5 µl of the first-strand cDNA to the PCR mix containing: 1 µm of each primer (20 µm), 1 µl of 10 mm dNTP mix, 5 µl of 10× PCR buffer, 1·2 µl of 1·5 mm MgCl2, 0·2 µl of Taq DNA polymerase (50 U/ml) and 31 µl of DEPC-treated water. The mixture was subjected to amplification using a thermal cycler (Hybaid, Ashford, UK) at 94° for 1 min (IL-4 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]) or 30 seconds (IFN-γ), 60° for 2 min (IL-4 and GAPDH) or 62° for 1 min (IFN-γ), and 72° for 3 min (GAPDH and IL-4) or 90 seconds (IFN-γ), with a final elongation step at 72° for 10 min. PCR amplification was carried out for 35–40 cycles. PCR fragments were separated by agarose-gel electrophoresis (2% gel), stained with ethidium bromide and then viewed under a UV transilluminator. The primer sequences were as follows: IL-4, sense GAATGTACCAGGAGCCATATC; antisense CTCAGTACTACGAGTATTCCA; and IFN-γ, sense TCTCTCCTGCCTGAAGGAC; antisense ACACAGTGATCCTGTGGAA. The amplified DNA was 399 bp for IL-4 and 460 bp for IFN-γ. The PCR conditions were optimized for each primer pair with a linear relationship between RNA input and cDNA output.

NO determination

Saliva was collected from mice after intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of pilocarpine to stimulate saliva flow. NO in saliva was determined by measuring nitrite accumulation, a stable metabolic product of NO with oxygen, as determined by the Griess reaction.20,21 Briefly, equal volumes of saliva and Griess reagent (0·5% sulphanilamide and 0·05% N-1-napthylethelenediamide hydrochloride in 2·5% phosphoric acid) were mixed at room temperature. After 5 min, the absorbance was measured at 550 nm using an ELISA microplate reader. The concentration of nitrite was determined by a standard curve prepared with sodium nitrite (1–200 µm).

Saliva collection

Mice were anaesthetized by i.p. injection with 75 µl of ketamine:xylazil (100 mg/ml:20 mg/ml). Saliva was collected from each mouse using a glass pipette after cholinergic stimulation by i.p. injection of pilocarpine (2·5 µg/20 g of body weight).

Effect of saliva on C. albicans viability

Saliva was collected at various time-points from mice following infection with C. albicans. Immediately after collection, 250 µl of saliva was added to 1 × 107 C. albicans blastospores. After incubation at 37° for 150 min, the viability of blastoconidia was determined by plating serial 10-fold dilutions of the yeast suspension onto Sabouraud dextrose agar. Colony counts were determined after incubation for 24 hr at 37°.

Treatment of infected mice with NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (MMLA)

Mice were infected orally by topical application with 1 × 108 yeast cells. The following day, mice were injected i.p. with a specific inhibitor of NO synthase, MMLA, at 50 mg/kg9,10 every 2 days for 8 and 13 days in BALB/c mice and DBA/2 mice, respectively. Meanwhile, the control mice were infected with C. albicans and received sterile PBS instead of MMLA by i.p. injection. At various time-points, mice were killed and the number of yeast cells in the oral cavity was determined.

Treatment of saliva with NO scavenger

Immediately after collecting saliva from mice infected with C. albicans, the saliva was treated with or without total haemoglobin as a NO scavenger for 5 min after which time the yeasts (1 × 107) were added, mixed and then cultured. After incubation at 37° for 150 min, the fungal growth was assessed by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of each sample onto Sabouraud dextrose agar. Colony growth was expressed as CFU/ml.

Infection and treatment with αIL-4 monoclonal antibody (mAb)

Mice were infected with C. albicans and then followed-up by treatment with αIL-4 antibody, as described previously.12 Briefly, BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with 30 µg of rat anti-rIL-418 (clone 11B11; PharMingen), or with the purified rat IgG1-matched isotype, in 200 µl of PBS per mouse, on days 1, 3 and 5 after oral infection with 108 yeast cells. At various time-points after the final injection, the mice were anaesthetized and the saliva collected for nitrite determination as described above.

Statistical analysis

Differences between the control and experimental groups were analysed by using the Student's t-test. A P-value of < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

NO concentration in the saliva of infected mice

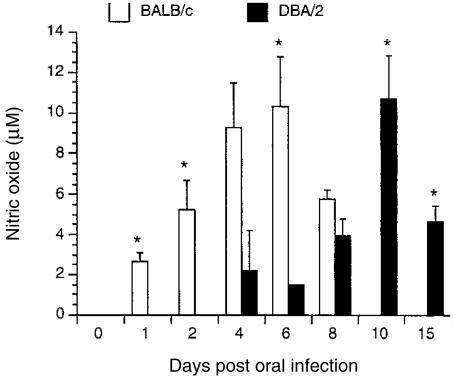

Figure 1 shows the kinetics of nitrite production in saliva from BALB/c and DBA/2 mice infected with C. albicans. In BALB/c mice, NO production was detected 1 day after infection and peaked on day 6 before decreasing to an undetectable level by day 10. In contrast, NO production was delayed in DBA/2 mice with levels first becoming detectable on day 4; this was followed by a sharp decline on day 6 before the NO level peaked on day 10 and then showed a decrease by day 15. Non-infected mice had low-to-undetectable levels of nitrite in saliva (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Nitric oxide (NO) production in saliva from mice infected with Candida albicans. BALB/c and DBA/2 mice were orally infected with C. albicans. At various time-points after infection, saliva was collected for determination of nitrite concentrations by the Griess reaction. Results shown represent the mean values + standard error of the mean for five mice. *P < 0·05 compared with values from control mice.

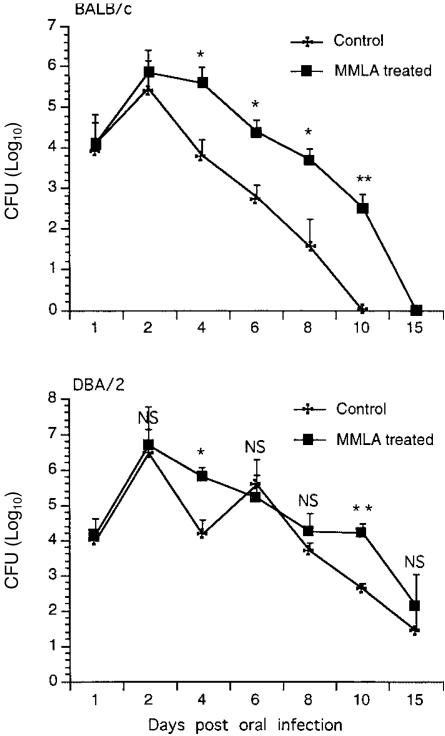

Effect of treatment of infected mice with NO inhibitor (MMLA)

In BALB/c mice, after an initial increase in colonization on day 2 in both control and MMLA-treated groups following oral infection, the levels of colonization thereafter were higher in treated groups than in control groups. The rate of clearance of the yeasts was slower in MMLA-treated mice than in control mice. In DBA/2 mice, after a peak level of colonization on day 2 for both control and treated mice, there was a sharp decline in colonization by day 4 in the control mice, but not in the treated mice, where high levels of colonization were still detected. On day 6, a repeat cycle of infection was noted in control mice, but not in treated mice, with levels of colonization similar to those of controls. Yeasts were rapidly cleared in control mice, but not in treated mice where the level of colonization remained high at day 10 before declining to levels seen in control mice by day 15. The kinetics of infection and the clearance rate correlated (P < 0·05 and P < 0·01) with the production of NO (Fig. 2), suggesting that host resistance to C. albicans infection is associated with the production of NO in the oral mucosa. Treatment of naive mice with MMLA had no detectable level of nitrite in saliva (data not shown). While treatment with MMLA to inhibit NO synthesis was effective by increasing colonization in the short term, it was not sufficient to prevent eventual elimination of colonization with C. albicans in the oral cavity.

Figure 2.

Patterns of colonization with Candida albicans in BALB/c and DBA/2 mice following treatment with NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (MMLA). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with an inhibitor of nitric oxide (NO) synthase, MMLA, every 2 days for 8 and 13 days in BALB/c mice and DBA/2 mice, respectively, after which the levels of colonization in the oral mucosa were assessed. Results shown represent the mean values + standard error of the mean for five mice. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 compared with values from control mice.

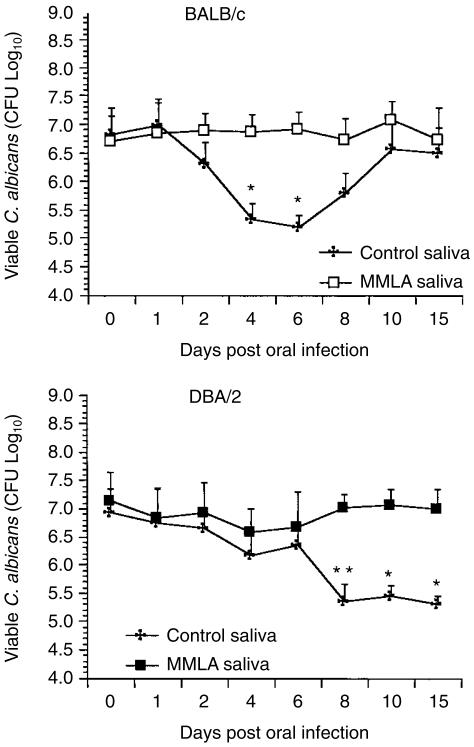

Effect of NO in saliva on C. albicans viability

To determine whether the production of NO in saliva is involved in the clearance of yeast from the oral mucosa, mice were infected with C. albicans and then treated with MMLA. Saliva was collected and tested for its effect on the growth of C. albicans in culture. As shown in Fig. 3, a 2-log reduction in C. albicans viability was noted when saliva was collected from BALB/c control mice on days 4 and 6 compared with saliva collected from MMLA-treated mice. A similar effect on C. albicans viability was detected with saliva collected from days 8–15 in DBA/2 mice. While the effect of saliva on C. albicans viability from BALB/c mice appeared to decline to control levels by day 10, it was not the case with DBA/2 mice where the candidastatic effect persisted in saliva for up to 15 days.

Figure 3.

Effect of saliva on Candida albicans viability. BALB/c and DBA/2 mice were infected orally with C. albicans. At various time-points after infection, saliva collected from individual mice was tested for its effect on the growth of C. albicans in vitro. Results shown represent the mean values + standard error of the mean for five mice. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 compared with values from NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (MMLA)-treated mice.

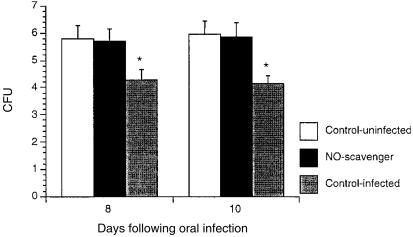

Effect of NO scavenger on candidacidal activity in saliva

To determine whether the candidacidal activity of saliva was caused by NO, total haemoglobin (an NO scavenger) was added to saliva collected from infected or uninfected DBA/2 mice before incubation with C. albicans. As shown in Fig. 4, saliva from infected mice significantly inhibited the growth of C. albicans compared to saliva treated with haemoglobin (P ≤ 0·05), indicating that NO was responsible for the antifungal activity in saliva.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of antifungal activity in saliva treated with a nitric oxide (NO) scavenger. DBA/2 mice were infected with Candida albicans in the oral cavity. At various time-points, saliva was collected and tested for its capacity to inhibit fungal growth in culture with or without haemoglobin (10% vol/vol). After incubation for 2 hr at 37°, the viability of C. albicans was assessed. Data shown represent the mean values + standard error of the mean for five mice. *P ≤ 0·05 compared with values from control mice.

Expression of cytokine and NO production in mice infected with C. albicans

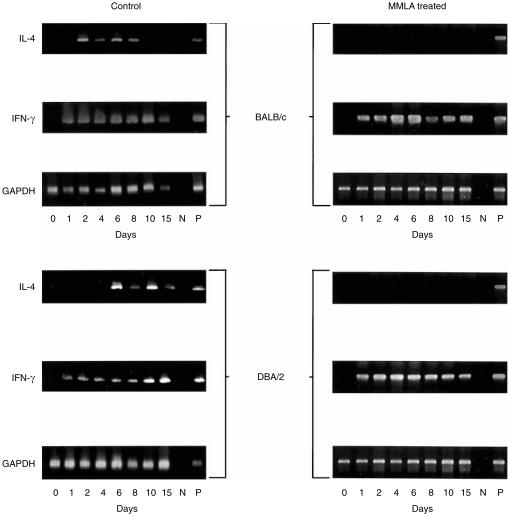

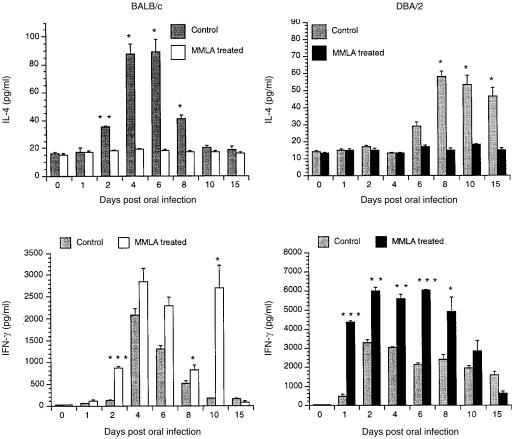

We have shown that a balanced cytokine response characterized by IL-4 and IFN-γ production is important in mucosal protection in the current model of oral infection with C. albicans.12 To determine whether resistance to infection of mice with C. albicans involving NO is associated with the production of cytokine, IL-4 and IFN-γ gene expression and protein production were measured in cultures of CLN cells stimulated with C. albicans antigens. As shown in Fig. 5, treatment of C. albicans-infected mice with MMLA abrogated mRNA gene expression for IL-4 but not IFN-γ. This is reflected in IL-4 production in the culture supernatant, as shown in Fig. 6, which was significantly inhibited in both BALB/c and DBA/2 mice. In contrast, a marked increase in IFN-γ production (Fig. 6) was observed in both BALB/c and DBA/2 mice following infection and treatment with MMLA. Higher amounts were produced in DBA/2 mice than in BALB/c mice, at levels that were sustained for up to 8 and 10 days, respectively.

Figure 5.

mRNA gene expression of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in cervical lymph node (CLN) cells from mice infected with Candida albicans. BALB/c and DBA/2 mice were infected orally with C. albicans. At various time-points after infection, total RNA was extracted from CLN cells to determine the levels of cytokine gene expression by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) amplification. Equivalent loading of each sample was determined by the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) message shown. N, negative control; P, positive control.

Figure 6.

Interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production by cervical lymph node (CLN) cells in culture stimulated with Candida albicans. BALB/c and DBA/2 mice treated or untreated with NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (MMLA) were infected orally with C. albicans. At various time-points after infection, CLN cells were isolated and then stimulated in culture with C. albicans for 3 days, after which time the amounts of IL-4 and IFN-γ in culture supernatants were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data shown represent the mean values + standard error of the mean for five mice. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·0001 compared with values from untreated mice.

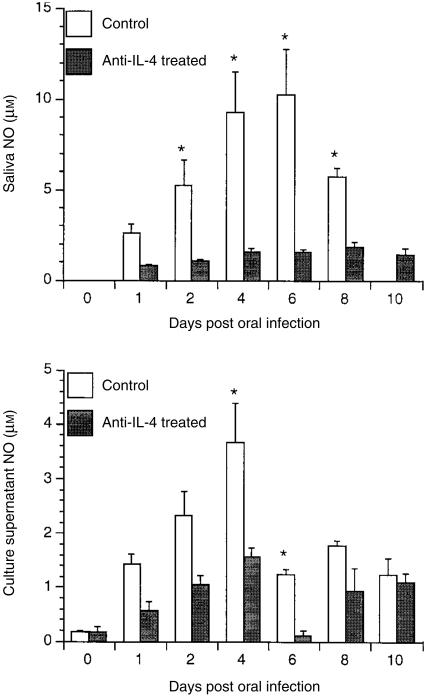

Effect of treatment with αIL-4 on NO production in saliva from mice infected with C. albicans

As shown in Fig. 7, infected BALB/c mice injected with rat anti-mouse IL-4 produced significantly less saliva nitrite at days 2, 4, 6 and 8 compared with those injected with a matched rat IgG isotype control in PBS. Inhibition of NO production was also observed in culture supernatants from CLN cells stimulated with C. albicans antigens, especially on days 4 and 6 after injection of αIL-4. NO production in unstimulated cultures was low to undetectable (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Nitric oxide (NO) production in saliva and culture supernatant of cervical lymph node (CLN) cells from mice treated with anti-interleukin-4 (αIL-4). BALB/c mice, treated or untreated with αIL-4, were challenged orally with Candida albicans. At various time-points after oral challenge, CLN cells were isolated and then stimulated in culture with C. albicans for 3 days, after which the NO concentrations in saliva and in culture supernatants of CLN cells, stimulated or unstimulated with C. albicans antigens, were measured. Results shown represent the mean values + standard error of the mean for five mice. *P < 0·05 compared with values from control mice.

Discussion

This study used a murine model of oral candidiasis, which included ‘infection-resistant’ BALB/c mice and ‘infection-prone’ DBA/2 mice,12 to show that NO is involved in host resistance to infection with C. albicans. Oral infection with C. albicans led to increased production of NO in saliva, which inhibited the growth of yeast in vitro. Treatment of mice with an inhibitor of NO synthesis, MMLA, reduced saliva levels of nitrite, which correlated with an increase in C. albicans viability. Reduction in NO production following MMLA treatment correlated with an abrogation of IL-4, but not IFN-γ, mRNA gene expression in regional lymph node cells. The down-regulation of IL-4 production was accompanied with an increase in IFN-γ, particularly in the infection-‘prone’ strain DBA/2. Treatment of infected mice with αIL-4 led to a decrease in the nitrite concentration in saliva and supernatant of cultured CLN cells (data not shown). These results support previous conclusions that IL-4 is linked to host protection against C. albicans infection in oral candidiasis.12 In addition, they suggest that NO is an effector molecule involved in controlling colonization of the mucosal surface with C. albicans.12

NO is an antimicrobial factor generated by NO synthase in activated macrophages and plays a role in the killing of bacteria, protozoa and fungi.22,23 Recent studies have shown that increased NO production is associated with both macrophage candidacidal activity and resistance of mice to C. albicans infection.8,11 The present study indicates that C. albicans infection results in a rapid increase in the concentration of nitrite in the saliva of ‘infection-resistant’ BALB/c mice, but has less effect in ‘infection-prone’ DBA/2 mice. In both mouse strains, however, resistance to infection was associated with the production of NO, as mice injected with the NO inhibitor, MMLA, showed an increased colonization and a delayed clearance of yeast. This was particularly apparent in the ‘infection-resistant’ BALB/c mice. These observations support data of a previous study reporting that poor candidacidal activity of macrophages from DBA/2 correlates with a reduced nitrite production capacity.11 This is the first study to demonstrate that NO mediates protection against C. albicans within the oral mucosa. It is consistent with studies, in orogastric candidiasis, where inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA expression was increased in the gastric mucosa of immunodeficient mice infected with C. albicans, and where treatment with a NO inhibitor led to more severe infection.10 In the present study, however, treatment with MMLA did not prevent eventual elimination of the yeasts from the oral cavity. This suggests that, while effective in the short term (as shown by increased colonization), the doses used may not be sufficient to inhibit NO synthesis in a sustained manner over a longer period of time. This may lead to the recovery of NO synthesis and the eventual elimination of C. albicans.

The effector mechanisms by which NO contributes to protection against C. albicans infection at the mucosal surface remain unclear. A recent study reported that nitrite was candidacidal in vitro at low pH, while NO was more effective against blastospores than hyphae.24 In addition, NO has high candidacidal activity in vitro.25 In the present study, we showed that saliva from mice infected with C. albicans inhibited the growth of yeast cells in vitro. Addition of a NO scavenger to the saliva led to a reduction in the candidacidal activity. Furthermore, the C. albicans was less sensitive to saliva from infected mice when treated with a NO inhibitor (MMLA) compared to the saliva from control mice, confirming that the candidacidal activity was caused by NO. A reduction in the candidacidal activity following treatment with MMLA correlated with results of production of NO in mice infected with C. albicans. The effect of candidacidal activity in saliva was detected early in BALB/c mice compared with the delayed appearance in DBA/2 mice. This variable production of NO in saliva may explain the rapid clearance rate of the yeasts in ‘infection-resistant’ BALB/c mice (which have a higher and more rapid production of NO) compared to ‘infection-prone’ DBA/2 mice, following infection with C. albicans.

Numerous studies indicate that T cells (through cytokine activation of macrophages and neutrophils) play an important role in the resistance to infection with C. albicans.26,27 The generation of NO is regulated by Th1 and Th2 cells and their secreted cytokines, such as IFN-γ and IL-4. For example, loss of iNOS expression and the consequent defective production of NO led to an increase in the Th1 response,28 whereas NO enhanced the expression of the Th2 cytokine, IL-4.16 We have recently reported that a balanced Th1/Th2 response characterized by both IL-4 and IFN-γ production is linked to resistance of mice to oral candidiasis.12 The present study showed that inhibition of NO production by MMLA in mice resulted in suppression of IL-4 mRNA gene expression and its protein production and an enhancement of IFN-γ production in regional lymph node cells. In addition, we showed that neutralization of IL-4 in vivo by administration of αIL-4 antibody led to a decreased production of NO in saliva and by cultured CLN cells stimulated with C. albicans antigen. In our previous studies,12 neutralization of IL-4 in vivo also led to an increase in colonization and a delayed clearance of C. albicans from the oral mucosa. Taken together, these data provide evidence that resistance to infection with C. albicans is associated with a positive paracrine relationship between IL-4 and NO. The cell source of each factor cannot be established from these studies, although the stimulation data suggests that this paracrine ‘loop’ is T-cell dependent. Therefore, an impaired production of NO with a down-regulation of IL-4, or vice versa, leads to lower resistance to infection with C. albicans and is associated with a switch in the Th1/Th2 balance characterized by an increased production of IFN-γ.

Macrophages and neutrophils are the only cells to have been shown to be cytotoxic to the blastoconidia and hyphal forms of C. albicans, as a result of the production of NO.8,9,25 Direct contact with activated T cells and cytokines that include IL-4 and IFN-γ is necessary for the full expression of candidacidal activity and resistance to infection.9,23,29 It has been reported that γ/δ T cells enhance resistance to mucosal candidiasis by stimulating macrophage NO production and candidacidal activity.30 We and others have shown that oral infection with C. albicans resulted in an increased number of γ/δ T cells in the oral mucosa17 and in regional lymph nodes,12 suggesting that γ/δ T cells are important in the resistance to oral candidiasis, possibly through a mechanism that involves a cytokine-mediated activation of macrophages to produce NO.

References

- 1.Bodey GP. Infection in cancer patients. Am J Med. 1986;81A:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho YS, Choi HY. Opportunistic fungal infection among cancer patients. A ten year autopsy study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979;72:617–22. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/72.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein J, Truelove E, Izutau K. Oral candidiasis: pathogenesis and host defence. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:96–106. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odds FC. Candida and Candidosis. London: Bailliere Tindall; 1988. Factors that predispose the host to candidosis; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brummer E, Stevens D. Candidacidal mechanisms of peritoneal macrophages activated with lymphokines or gamma interferon. J Med Microbiol. 1989;28:173–81. doi: 10.1099/00222615-28-3-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiemstra P, Eisenhauer P, Harwing S, Van den Barselaar M, Van furth R, Lehrer R. Antimicrobial proteins of murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3038–46. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.3038-3046.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe K, Kagaya K, Yamada T, Fakazawa Y. Mechanism for candidacidal activity in macrophages activated by recombinant gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1991;59:521–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.521-528.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cenci E, Romani L, Mencacci A, Spaccapolo R, Schiaffella E, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 inhibit nitric oxide-dependent macrophage killing of C. albicans. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1034–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Balish E. Candidacidal activity of macrophages from immunocompetent and congenitally immunodeficient mice. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:180–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Warner T, Balish E. Nitric oxide enhances resistance of SCID mice to mucosal candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:192–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Balish E. Nitric oxide production does not directly increase macrophage candidacidal activity. Infect Immun. 1995;6:1142–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1142-1144.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elahi S, Pang G, Ashman RB, Clancy R. Cellular and cytokine correlates of mucosal protection in a murine model of oral candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5771–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5771-5777.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liew FY. Regulation of lymphocyte function by nitric oxide. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:396–408. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor-Robinson A, Liew FY, Severn A. Regulation of the immune response by nitric oxide differentially produced by T helper type 1 and 2 cells. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:280–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes PJ, Liew FY. Nitric oxide and asthmatic inflammation. Immunol Today. 1995;16:128–30. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang R, Linfeng MH, Liu WH, Lai MZ. Nitric oxide increased IL-4 expression in T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;90:364–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1997.00364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakir J, Cote L, Coulombe C, Delasriers N. Differential pattern of infection and immune response during experimental oral candidiasis in BALB/c and DBA/2 (H-2d) mice. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1994;9:88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1994.tb00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mencacci A, Spaccapelo R, Del Sero G, Enssle KH, Cassone A, Bistoni F, Romani L. CD4+ T helper cell responses in mice with low-level C. albicans infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4907–14. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4907-4914.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romani L, Mencacci A, Cenci E, Spaccapelo R, Mosci P, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. CD4+ subset expression in murine candidiasis. Th responses correlate directly with genetically determined susceptibility or vaccine-induced resistance. J Immunol. 1993;150:925–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrate and [15N] nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131–44. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moncada S, Palmer RMJ, Higges EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alspaugh J, Granger D. Inhibition of Cryptococcus neoformans replication by nitrogen oxides supports the role of these molecules as effectors of macrophage-mediated cytostasis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2291–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2291-2296.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan J, Xing Y, Magliozzo R, Bloom B. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1111–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abaitua F, Rementeria A, Sanmillan R, Eguzkiza A, Rodriguez J, Ponton J, Sevilla M. In vitro survival and germination of C. albicans in the presence of nitrogen compounds. Microbiology. 1999;145:1641–7. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fierro M, Barja-Fidalgo C, Cunha FG, Ferreira HS. The involvement of nitric oxide in the anti-C. albicans activity of rat neutrophils. Immunology. 1996;89:295–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantorna M, Balish E. Mucosal and systemic candidiasis in congenitally immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1093–100. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1093-1100.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantorna MT, Balish E. Role of CD4+ lymphocytes in resistance to mucosal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2447–55. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2447-2455.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei X-Q, Charles IG, Smith A. Altered immune responses in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthetase. Nature. 1995;375:408–13. doi: 10.1038/375408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao X, Stouat RD. T cell-mediated cognate signalling of nitric oxide production by macrophages. Requirement for macrophage activation by plasma membranes isolated from T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2916–21. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones-Carson J, Vazquez-torres A, Van der Heyde Warner T, Wagner R, Balish E. γδ T cell-induced nitric oxide production enhances resistance to mucosal candidiasis. Nat Med. 1995;1:552–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]