Abstract

Plant peroxisomes perform multiple vital metabolic processes including lipid mobilization in oil-storing seeds, photorespiration, and hormone biosynthesis. Peroxisome biogenesis requires the function of peroxin (PEX) proteins, including PEX10, a C3HC4 Zn RING finger peroxisomal membrane protein. Loss of function of PEX10 causes embryo lethality at the heart stage. We investigated the function of PEX10 with conditional sublethal mutants. Four T-DNA insertion lines expressing pex10 with a dysfunctional RING finger were created in an Arabidopsis WT background (ΔZn plants). They could be normalized by growth in an atmosphere of high CO2 partial pressure, indicating a defect in photorespiration. β-Oxidation in mutant glyoxysomes was not affected. However, an abnormal accumulation of the photorespiratory metabolite glyoxylate, a lowered content of carotenoids and chlorophyll a and b, and a decreased quantum yield of photosystem II were detected under normal atmosphere, suggesting impaired leaf peroxisomes. Light and transmission electron microscopy demonstrated leaf peroxisomes of the ΔZn plants to be more numerous, multilobed, clustered, and not appressed to the chloroplast envelope as in WT. We suggest that inactivation of the RING finger domain in PEX10 has eliminated protein interaction required for attachment of peroxisomes to chloroplasts and movement of metabolites between peroxisomes and chloroplasts.

Keywords: β-oxidation, biogenesis, glyoxysome

Eukaryotic peroxisomes perform multiple metabolic processes, including fatty acid β-oxidation and H2O2 inactivation by catalase (1). In plants, leaf peroxisomes interact with chloroplasts and mitochondria in photorespiration, a metabolic pathway in which two molecules of glycolate are converted in a series of enzymatic reactions through glyoxylate, glycine, serine, and hydroxypyruvate into CO2 and phosphoglycerate (2–4). The advantage of the photorespiratory cycle is twofold. When CO2 in the plant canopy becomes limited in supply (which is frequent at midday), ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase functions as an oxygenase and protects the photosynthetic machinery from photodamage. It does so by using energy for respiration, producing CO2, and regenerating the substrate to be used in CO2 fixation. Mutants lacking enzymes of the photorespiratory cycle are incapable of surviving in ambient air but are able to grow normally in atmosphere enriched in CO2 because ribulose-bisphosphate oxygenase is suppressed (2). Plant peroxisomes are necessary for jasmonic acid biosynthesis (5) and are implicated in conversion of indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) into indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (6–8). Specialized peroxisomes called glyoxysomes contain glyoxylate cycle enzymes for lipid mobilization in germinating oil seedlings and senescing leaves (1).

The peroxins (PEX proteins) are a set of cytosolic and membrane proteins involved in peroxisome biogenesis. Mutations of PEX genes leading to impaired peroxisome biogenesis result in severe metabolic and developmental disturbances in yeasts, humans (Zellweger syndrome), and plants (9–11). PEX10, PEX12, and PEX2 encode integral membrane proteins distinct in their primary sequence except for a shared C3HC4-type RING finger motif in the C-terminal domain. Loss of function of any one of these three genes in Arabidopsis causes embryo lethality at the heart stage, supporting the notion that they act together during peroxisome biogenesis (12–15). Glyoxysomes and leaf peroxisomes originate de novo, presumably with an involvement of the ER, and multiply by division (9–11). Their developmental transition with replacements of enzyme content is induced by light (16–18).

The seed lethal T-DNA disruption phenotype of PEX10 implicates this membrane PEX in multiple cell biological functions, but nothing is yet known about the physiological role of PEX10 in plants. We therefore tried to elucidate its function with conditional sublethal mutants. Four different T-DNA insertion lines expressing pex10 with a dysfunctional C3HC4 RING finger were created in an Arabidopsis WT background. They could be normalized by growth in an atmosphere of high CO2 partial pressure, indicating a defect in photorespiration. Gene expression, biochemical analyses, and light and electron microscopy of these conditional mutants were undertaken to identify the role of PEX10 in peroxisome proliferation, attachment to chloroplasts, matrix protein import, and photorespiration.

Results

Generation of Conditional Sublethal Mutants Expressing pex10 with a Dysfunctional Zn Finger (ΔZn Lines).

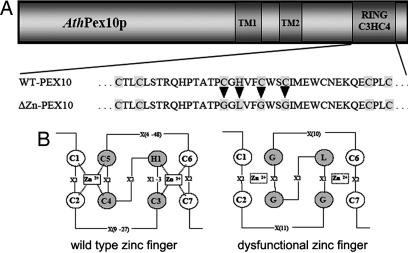

The motif C2GLG2C2, unable to coordinate Zn ions in the C3HC4 Zn finger of pex10 cDNA, was created by mutating C3, C4, and C5 to G and H1 to L (Fig. 1). The mutated cDNA was cloned under control of the 35S promoter into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens vector pBI121 conferring kanamycin resistance and transformed into Arabidopsis Columbia WT plants. Screening of T2 transformants for noticeable phenotypes such as dwarfism and atrophy in normal air (360 ppm CO2) and under 5-fold elevated CO2 partial pressure (1,800 ppm CO2) identified four dwarfs that could be normalized by high CO2 [for details of progeny analysis see supporting information (SI) Text]. After verifying the phenotypes in T3 progenies, four lines (referred to as ΔZn1–4) with the following characteristics were established: in normal atmosphere, the plants grew as dwarfs with a 2- to 3-week-delayed development and retarded silique maturation, but under elevated CO2, the plants developed normally (Fig. 2A and B), which is typical for mutants impaired in photorespiration (2). Although seed yield was normal, ΔZn seeds were often smaller, shrunken, and less tightly filled with storage material (Fig. 2C). The weight of 1,000 seeds was 26.9 ± 0.4 mg for WT and 21.0 ± 1.6 mg for ΔZn1–4 grown in normal air, compared with 22.4 ± 0.1 mg for WT and 23.0 ± 2.5 mg for ΔZn1–4 grown under high CO2. Transmission electron microscopy of maturing embryos revealed no conspicuous structural difference between WT and ΔZn1–4 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

The dysfunctional Zn finger motif in AtPex10p. The amino acid changes resulting in a loss of Zn coordination sites are shown.

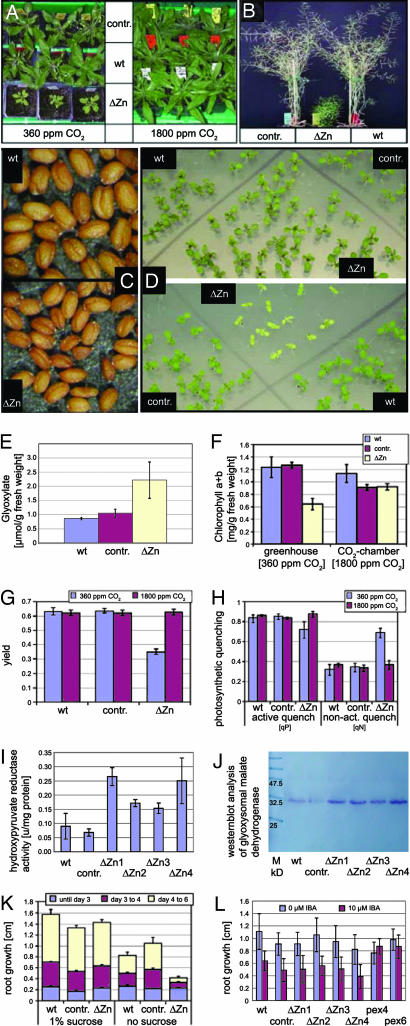

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the ΔZn lines, WT, and pB1727 vector control (contr). (A) Dwarfish growth of 4-week-old ΔZn plants under 360 ppm CO2 (Left) and normalization under 1,800 ppm CO2 (Right). (B) Six-week-old dwarfish ΔZn plant compared with WT and control. (C) Seeds of the ΔZn mutant are smaller than the WT seeds. (D) Ten-day-old ΔZn plants grown in atmospheric CO2 (at the bottom) show dwarfism and chlorosis that are normalized under 5-fold elevated CO2 partial pressure (at the top). (E) Increased glyoxylate accumulation in the peroxisomes of the ΔZn. (F) ΔZn plants regained WT chlorophyll a+b content after transfer to high CO2. (G) Photosynthetic yield of photosystem II in light-adapted leaves after a saturating actinic light pulse. Yield in ΔZn is decreased in low CO2. (H) Photochemical active quenching (qP) reduced and nonactive quenching (qN) increased in ΔZn in normal atmosphere. (I) Increased hydroxypyruvate reductase activity in ΔZn organellar pellets. (J) Increased glyoxysomal malate dehydrogenase in ΔZn. (K) Lack of sucrose causes reduced root growth from day 3 after germination in ΔZn with beginning photoautotrophy. (L) Auxin precursor IBA inhibits root growth of WT, ΔZn, and control, but not of IBA-resistant pex4 and pex6 seedlings.

ΔZn1–4 were similarly dwarfed with ΔZn1 showing sometimes a slightly more severe phenotype under strong light. Transcript levels of the parental WT gene and the mutated pex10 gene carrying additionally a MbiI restriction site marker for recognition were examined by RT-PCR. A 248-bp fragment spanning the WT or the mutated Zn finger motif was amplified in approximately equal amounts, indicating that the authentic and mutant PEX10 genes exhibited similar transcript levels in all ΔZn lines. Furthermore, all ΔZn lines exhibited approximately equal transcript amounts versus WT and vector control plants (Fig. 3).

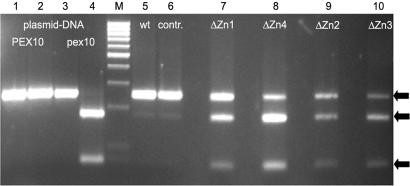

Fig. 3.

Transcript levels of PEX10 and pex10 after amplification by RT-PCR and digestion with MbiI; plasmid DNA was used as control. Lanes 1 and 3, undigested; lanes 2 and 4–10, digested with MbiI. Arrows indicate the undigested 248-bp PCR product of WT PEX10 and the 176-bp and 72-bp fragments of the mutated pex10 after digestion with MbiI. ΔZn lines exhibit both transcripts in approximately equal amounts. M, 100-bp ladder.

A T-DNA insertion disrupting the fourth exon of the AtPEX10 gene leads to embryo lethality; the mutant can be rescued by transformation with the WT AtPEX10 cDNA (12). To characterize the significance of the C3HC4 Zn finger motif for the function of PEX10, the heterozygous kanamycin-resistant pex10 disruption line was transformed with ΔZn-pex10 under control of the 35S promoter, by using the Bar resistance gene as selection marker (12). Forty-eight double-resistant seedlings, carrying both the insertion and the ΔZn-pex10, were obtained. Three pairs of PCR primers diagnostic for the presence of at least one intact genomic copy of PEX10, the transgenic ΔZn-pex10, and the insertion element permitted genotyping of all possible segregants (see figure 1 D and G in ref. 12). None of the 48 transgenic plants could survive despite knockout of the WT by the overexpressed ΔZn-pex10; siliques of the surviving plants exhibited the same ratio of segregating seeds as the noncomplemented insertion line, i.e., green maturing to white lethal seeds (data not shown). Thus, mutation of the C3HC4 Zn finger motif conferred the same lethality as the complete disruption of PEX10, and the phenotypes of ΔZn1–4 were caused by competition between the endogenous PEX10 and the mutated pex10 transcripts.

Leaf Peroxisomes in the ΔZn Lines Are Impaired in Photorespiration.

ΔZn plants showed the dwarfish and chlorotic phenotype in normal air after 10 days (Fig. 2D) and were used for characterization. We quantified the parameters that are associated with defective photorespiration, such as glyoxylate level, the amount of chlorophyll a and b and carotenoids (xanthophylls and carotenes), and the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II. All four ΔZn lines exhibited the same phenotype to a similar quantitative degree (Fig. 2 E–H).

An abnormally high level of glyoxylate was detected photometrically after reaction with phenylhydrazine in the presence of K3Fe(CN)6 (Fig. 2E). The mutant plants regained WT chlorophyll a and b contents after transfer to high CO2 (Fig. 2F) but had a lowered content of carotenoids compared with WT grown in normal air and transferred to high CO2 (data not shown). Photosynthetic parameters were evaluated by chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics with the portable fluorometer PAM-2000 (Fig. 2 G and H). The ΔZn plants revealed a decreased photosystem II quantum yield under normal atmosphere; under high CO2 these values reached WT levels (Fig. 2G). As a parameter for the redox state of the primary electron acceptor in photosystem II, photochemical quenching was determined. Under atmospheric CO2 conditions, active quenching was decreased and nonactive quenching was increased in the ΔZn lines, indicating an ineffective photosynthesis system. Under 5-fold-elevated CO2 partial pressure these parameters did not differ from WT and vector controls (Fig. 2H).

The high level of glyoxylate indicates a defect in peroxisomal metabolism, possibly a deficiency in serine-glyoxylate aminotransferase activity. We determined the serine-glyoxylate aminotransferase activity by measuring the consumption of glyoxylate with serine as amino donor in protein extracts of 10-day-old plants. We found equal levels in both WT and ΔZn plants: consumption of 0.24 μmol of glyoxylate min−1·mg−1 of protein compared with 0.22 μmol of glyoxylate min−1·mg−1 of protein. We compared hydroxypyruvate reductase and glyoxysomal malate dehydrogenase amounts in crude organelle pellets of ΔZn plants, WT, and vector control plants (Fig. 2 I and J). The enzyme content in the ΔZn plants was significantly increased as compared with control plants.

Glyoxysomes in the ΔZn Lines Are Not Impaired in β-Oxidation During Germination and Seedling Establishment.

To assess β-oxidation in glyoxysomes, we tested sugar dependence during germination and IBA response of the ΔZn lines. Peroxisomal mutant seedlings of oil seed species such as Arabidopsis grow poorly in the absence of exogenous sugar (19). The developmental delay of ΔZn plants was quantified by measuring the root growth on medium either with or without 1% sucrose in the light (Fig. 2K). Mutant plants developed normally without exogenous sugar until days 3–4 of germination, so long as lipid mobilization was the limiting factor. However, a lag in root growth was seen from the beginning of photoautotrophy at day 4 on medium lacking sucrose, when peroxisomal transport of metabolized phosphoglycolate starts to play a crucial role for the normal photosynthetic development of seedlings.

Mutants defective in β-oxidation are resistant to the inhibitory effect of IBA on root elongation, because the glyoxysomes cannot convert IBA into IAA (6). Root growth was determined in WT, vector control, and ΔZn seedlings on medium with 1% sucrose with or without 10 μM IBA. pex6, which has photorespiration defects similar to the ΔZn lines (7), and pex4, which appears to grow normally (8), are IBA-resistant as seedlings and were used as positive controls (Fig. 2L). ΔZn seedlings responded to the inhibitory effect of IBA on root elongation similar to WT and vector control plants, whereas pex4 and pex6 seedlings exhibited the expected resistance to IBA.

Early normal development of the ΔZn seedlings implies that their glyoxysomes contain sufficient matrix enzymes to perform β-oxidation to mobilize stored lipids and to convert IBA into IAA. Glyoxysomal function thus appears to be unaffected by the overexpression of a dysfunctional PEX10 protein that impairs photorespiratory function in leaf peroxisomes.

Leaf Type Peroxisomes in ΔZn Lines Are Pleomorphic and Rarely Associated with Chloroplasts.

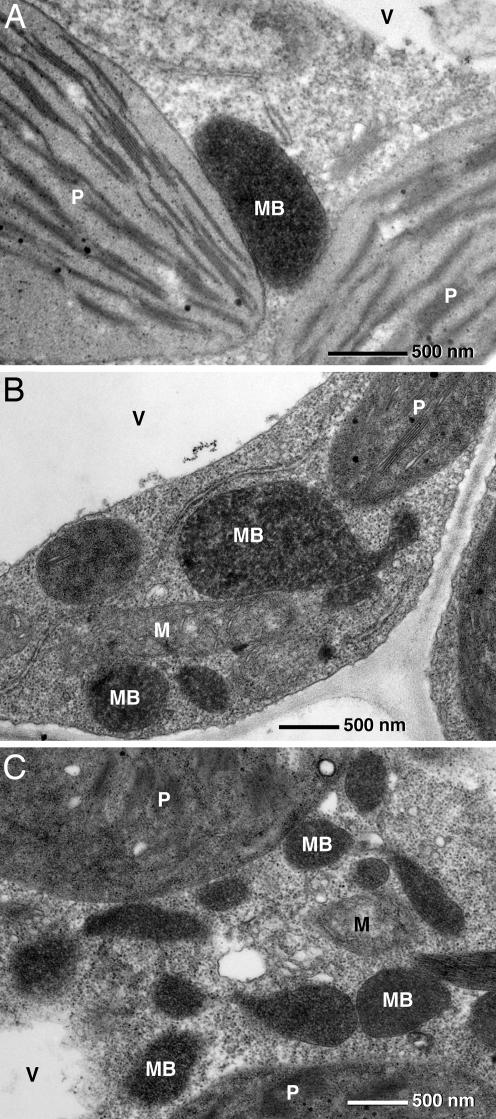

The morphology and association of leaf peroxisomes with other organelles in ΔZn seedlings were examined by quantitative transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 4) and light microscopy (Fig. 5). Peroxisomes are identified unequivocally by cytochemical staining for catalase (20). As exemplified in Figs. 4A and 5, WT image, the spherical or ovoid peroxisomes in the mesophyll cells of WT Arabidopsis thaliana had a diameter of 0.88 ± 0.23 μm (n = 50), were appressed to the envelope of chloroplasts, and were frequently in close physical contact with mitochondria. The peroxisomes of the ΔZn plants exhibit catalase activity equal to those of WT (Figs. 4 B and C and 5, image ΔZn1–4), but they varied considerably in size and shape and were rarely associated with chloroplasts. The ΔZn peroxisomes form chains, protuberances, and interconnected clusters within the cytoplasm (Fig. 5, image ΔZn1–4), possibly indicating an inhibition of the proliferating peroxisomes in their fission.

Fig. 4.

Electron micrographs of leaf tissue of WT (A) and ΔZn1 (B and C) plants stained for catalase activity with diaminobenzidine. The leaf peroxisomes of WT are ovoid and in physical contact with chloroplasts (A). Mutant ΔZn plants exhibit peroxisomes with catalase activity, however rarely associated with chloroplasts. Their shape is pleomorph, ranging from ovoid to elongated with protrusions (B). Clusters of peroxisomes forming local networks are frequent (C). P, chloroplast; V, vacuole; MB, microbody (peroxisome); M, mitochondrion.

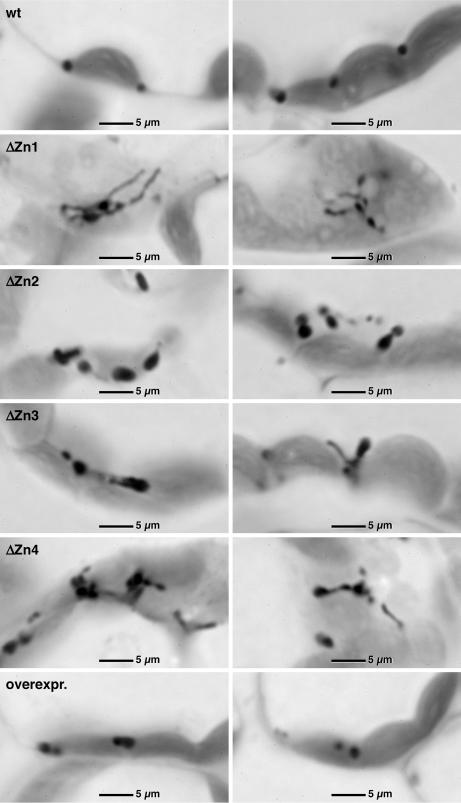

Fig. 5.

Light microscopy of semithin sections of leaf tissue from WT and ΔZn1–4 plants and AtPEX10-overexpressing plants stained for catalase activity with diaminobenzidine.

A quantitative analysis of the peroxisomal profiles revealed 3.32 ± 1.5 per WT (n = 25) and 9.0 ± 4.2 per ΔZn1 (n = 25) cell section (t for difference = 4.11; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001). In WT cells 88 ± 16% (n = 25) of peroxisomes were appressed to a chloroplast, whereas in an equal number of ΔZn1 cell sections 31 ± 21% were appressed to chloroplasts (t for difference = 27.7; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001). Measurements of the width of peroxisomal profiles (n = 50) in both WT and ΔZn1 did not reveal any significant difference with 0.88 ± 0.23 μm for WT and 1.28 ± 0.78 μm for ΔZn1 (t for comparison = 0.331; ∗∗∗, P = 0.07). However, there was a large difference in length. There were two peroxisomal populations in ΔZn1 cells, one with a normal length of 0.68 ± 0.15 μm (n = 29) and a second with a highly variable length of 3.51 ± 1.93 μm (n = 21) (tk for difference = 6.227; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001). The elongated structures could reach a length of 7 μm. Plants overexpressing WT PEX10 have normal-shaped peroxisomes attached to the chloroplast envelope (Fig. 5, image overexpr.).

Isolation and Mapping of Genomic Sequences Flanking the T-DNA Integration Sites in ΔZn Lines 1–4.

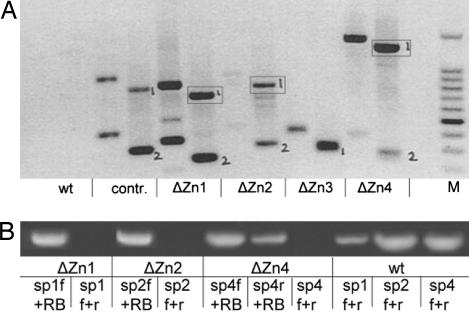

Southern blot analysis of the ΔZn lines revealed the presence of at least one integration site of the T-DNA carrying the pex10 cDNA (data not shown). Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR (TAIL-PCR) was carried out to identify genomic sequences flanking the T-DNA insertions (Fig. 6A). The two bands in the left lane for each plant DNA represent the products of the second cycle of the TAIL-PCR created with the arbitrary degenerate primer Nr.2 (AD-2) and the pBI right border primer (RB-2). The two bands in the right lane for the individual plant DNA amplificates (marked “1” and “2”) are the specific products of the third TAIL-PCR cycle. These PCR fragments are shorter than the bands in the left lane, because nested T-DNA primers were used to demonstrate the specificity of the PCR. WT DNA produced no PCR products. The bands marked “1” and “2” were sequenced and subjected to BLAST search. Bands marked with “2” were primarily T-DNA regions. The boxes in Fig. 6A mark the sequenced bands that matched different genomic sequences of A. thaliana. Thus, T-DNA integration into the different ΔZn lines occurred at different sites. In ΔZn1, the insertion was 335 bp upstream of the start codon within the 5′ UTR of an ortholog to the MtN24 gene of Medicago trunculata encoding a sequence similar to a prokaryotic membrane lipoprotein with a lipid attachment site (At3g55390). In ΔZn2, the integration was found 140 bp downstream of the stop codon within the 3′ UTR of a gene for glycerol-phosphodiesterase involved in glycerol metabolism (At5g58050). Integration in ΔZn4 occurred in the last intron of a gene for an unknown but expressed protein (At5g24314). TAIL-PCR for ΔZn3 did not reach genomic regions. Thus, the gene integrations, especially in the ΔZn1 and ΔZn2 lines, are unlikely to have interrupted expression of genes essential for photorespiration, and the phenotype must be due to the expression of the mutated PEX10 Zn finger protein. The integration sites were confirmed by genomic PCR by using primers specific for the affected genes. As expected, PCR using two gene-specific primers resulted in an absence of PCR products, whereas a combination of either of the appropriate gene-specific primers with primers for the pBI121 right border yielded PCR products confirming the results of the BLAST search (Fig. 6B). In ΔZn4, both specific primers in combination with the right border primers led to amplified DNA, indicating a full or partial tandem integration. Furthermore, crosses between homozygous ΔZn lines resulted in F1 progeny that were homozygous for the pex10 cDNA expression but heterozygous for the gene affected by the T-DNA insertion. These F1 progenies consistently exhibited the dwarf chlorotic ΔZn phenotype, again confirming that the expressed pex10 cDNA was responsible for the phenotype (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Localization of T-DNA integrations in ΔZn lines. (A) TAIL-PCR of ΔZn lines 1–4, WT, and pBI121 vector control (contr). PCR products marked “1” and “2” were sequenced and subjected to a BLAST search. PCR products “2” represent T-DNA regions. PCR products “1” (boxes) indicate positive matches in the Arabidopsis genome. (B) Genomic PCR of the ΔZn lines. The lack of DNA fragments obtained with ΔZn DNA from lines ΔZn1, ΔZn2, and ΔZn4 with the respective forward and reverse specific primers (sp1–4 f+r), and the creation of bands with the specific primers in combination with a right border primer (RB) for pBI121, confirm the T-DNA integrations within the genes proposed by TAIL-PCR and BLAST search. The band from ΔZn4 DNA created by the specific reverse primer (sp4r) and the RB primer, additionally to the band generated by the specific forward primer (sp4f) and the RB primer, indicates a full or partial inverse tandem integration into chromosomal DNA in ΔZn4. M, 100-bp ladder with the accentuated 500-bp fragment.

Knockout Lines with T-DNA Integrations in the Genes Containing the Transgenes in the ΔZn Lines Do Not Exhibit Impaired Photorespiration.

As a final confirmation that expression of pex10 is responsible for the dwarf chlorotic phenotype of ΔZn lines, knockout mutants with T-DNA integrations close to the integration sites of the pex10 cDNA in the ΔZn lines were examined. Homozygous knockout mutants were grown and genotyped to confirm the presence and position of the T-DNA insertions: SALK line 534800 and SAIL line 809777 with an insertion in the third exon of the gene At3g55390 affected in the ΔZn1 line, and SALK line 537722 with an insertion in the fifth exon of the gene At5g58050 affected in the ΔZn2 line. Their phenotype was similar to WT plants.

Discussion

Given the lethal phenotype of the previously analyzed null mutants of PEX10, we generated nonlethal partial loss-of-function mutants. By expressing a version of AtPEX10 cDNA with a dysfunctional Zn finger motif under the control of the 35S CaMV promoter, we obtained four dominant negative, conditional transformants with all landmarks of mutants compromised in photorespiration (Fig. 2). The parental WT gene and the mutated pex10 cDNA inserted in different regions of the Arabidopsis genome exhibited equal transcript levels in the four transformants supporting the rationale that the mutant protein lacking the RING finger metal ligands competes with the WT protein for interacting partners and will therefore interfere with the normal function of PEX10. By determining the sites of integration of three of the transgenes in the Arabidopsis genome and by analyses of knockout mutants of the genes targeted by the insertions, it was shown that they are not encoding proteins involved in photorespiration and thus the integrations were not responsible for the defective phenotype. The RING finger with the Zn metal ligands was required for normal-shaped peroxisome organelles that can physically associate through their single membrane with the outer membrane of the chloroplast envelope. This was correlated with proliferation of elongated peroxisomes that were unable to fission into normal-sized peroxisomes (Fig. 5). The dysfunctional RING finger did not affect the function of glyoxysomes that carry out β-oxidation and the glyoxylate cycle for lipid mobilization during oil seed germination; it did not influence the conversion of IBA into the plant growth hormone IAA. Furthermore, the dysfunctional RING finger did not impair the abundance of catalase within leaf peroxisomes as demonstrated in situ by cytochemical staining.

Functional photorespiration requires the localization of matrix enzymes within peroxisomes as well as the association of peroxisomes, chloroplasts, and mitochondria to enable the metabolite flow between these organelles. Our results let us conclude the necessity of the PEX10 Zn RING finger for the physical attachment between peroxisome membrane and chloroplast envelope. PEX10 is already known as an essential component of the peroxisomal protein import machinery and is thought to form a complex with the Zn RING finger proteins PEX2 and PEX12 in the peroxisomal membrane (9). We found equal or even enhanced activity levels for ΔZn plants compared with WT for the peroxisome marker enzymes serine-glyoxylate aminotransferase in protein extracts and hydroxypyruvate reductase and glyoxysomal malate dehydrogenase in organellar pellets. Because the function of the different PEX10 subdomains in matrix protein import is not known, it could be that the complex between the mutated PEX10 and the PEX2 and PEX12 is stabilized by the intact Zn finger of PEX2 and PEX12, thus allowing enzyme import into the abnormal-shaped peroxisomes. This interpretation is supported by the intact glyoxysome import machinery that might be inherited during developmental transition to leaf peroxisomes as demonstrated by the cytochemical catalase staining. We cannot, however, completely exclude the mislocalization of peroxisome enzymes to the cytosol, thus contributing to the defective photorespiration phenotype.

Efficient processing of glyoxylate into glycine for transport into mitochondria was severely curtailed. The elevated level of glyoxylate might be an inheritance of the glyoxysome metabolism rather than owing to the transfer from chloroplasts. Because the activity of serine-glyoxylate aminotransferase is comparable in WT and ΔZn plants, the reason for the disturbed metabolism is either the mislocalization of the enzyme to the cytosol or the lack of serine that is thought to be on the return trip from mitochondria.

It is of interest whether the RING finger domains of PEX12p and PEX2p are also required for generating associations between peroxisomes, chloroplasts, and mitochondria. In a comparable strategy, RNA interference plants with reduction of the PEX12 transcript were used to obtain sublethal mutants (15). These plants exhibited impaired peroxisome biogenesis and function and inhibition of plant growth. Down-regulation of PEX12 by RNA interference, however, yielded plants that were also less responsive to IBA.

In conclusion, transformants with peroxins mutated in an individual protein domain can detect novel functions of the peroxins. In the present case, the requirement of PEX10 for establishing the physical attachment of the peroxisome membrane to the chloroplast envelope has been demonstrated. It opens the way to finding out how this attachment shown in numerous published micrographs is established at the molecular level and which other proteins and possible transporters are involved. The attachment has been presaged in textbook cartoons to explain the metabolite flow from chloroplasts via peroxisomes to mitochondria and back via peroxisomes into the chloroplast to describe the photorespiratory pathway.

Methods

Generation of the Mutated C3HC4 Zn Finger.

Four point mutations were introduced into the Zn finger motif of the PEX10 cDNA with gene splicing by overlap extension (21, 22) to change the codons TGT or TGC for Cys into GGT for Gly and CAT for His into CTT for Leu (Fig. 1). The required primers are listed in SI Text.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from 100 mg of 3-week-old seedlings grown on MS plates. After cDNA first-strand synthesis, PCR was carried out with the PEX10 sense and antisense primers spanning a 248-bp-long fragment of the C terminus including the Zn finger and part of the 3′ UTR. The products of amplified PEX10/pex10 were purified, reamplified, digested with MbiI, and analyzed on a 3% agarose gel. The required primers are listed in SI Text.

Assays.

Glyoxylate was measured according to ref. 23, leaf pigments were measured as in ref. 24, serine-glyoxylate aminotransferase was measured as in ref. 25, and hydroxypyruvate reductase activity was measured as in ref. 26. Organellar pellets were prepared as in ref. 27. For Western blotting, polyclonal antibodies generated against glyoxysomal malate dehydrogenase were used (28). Defects in β-oxidation or photorespiration were assayed by growth on MS plates with or without 1% sucrose and measurement of root length (mean value of 20 plants) at days 3, 4, and 6. The inhibitory effect of IBA on root elongation (mean value of 20 plants) was tested as in ref. 6.

Photosynthetic Parameters.

The photosynthetic yield and the active and nonactive quenching were calculated from data collected with the portable pulse amplitude modulator fluorometer (PAM-2000; Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) at 25 ± 1°C and ambient CO2 partial pressure (29). For details see SI Text.

Electron and Light Microscopy.

Pieces of leaf tissue from 12-day-old light-grown control and ΔZn plants were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 75 mM sodium cacodylate/2 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.0) for 1 h at 25°C, rinsed several times in fixative buffer, and postfixed for 2 h with 1% osmium tetroxide in fixative buffer at 25°C. After two washing steps in distilled water, the pieces were stained en bloc with 1% uranyl acetate in 20% acetone for 30 min. Dehydration and embedding in Spurr's low-viscosity resin were essentially as in ref. 19. Ultrathin sections of 50–70 nm were cut with a diamond knife and mounted on uncoated copper grids. The sections were poststained with aqueous lead citrate (100 mM, pH 13.0). Micrographs were taken with an EM 912 electron microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an integrated OMEGA energy filter operated in the zero-loss mode. Specific localization of catalase activity was performed as in ref. 20. For light microscopy, semithin sections with a thickness of 500 nm were cut with a diamond knife, mounted onto glass slides, and embedded in epoxy resin.

Characterization of T-DNA Insertion Sites Within the Chromosomes ΔZn Lines.

TAIL-PCR (30) used a combination of primers recognizing the pBI121 right border (RB2 or RB3) and three different arbitrary degenerate primers (AD primers) annealing randomly in the genome of A. thaliana. The AD-2 primer combined with the RB3 primer resulted in the specific PCR products. Genomic PCR for verification of the integration sites identified by TAIL-PCR and BLAST research in ΔZn1, ΔZn2, and ΔZn4 used a primer pair annealing ≈900 bp upstream and downstream of the putative integration sites. The primers used and their locations are listed in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bonnie Bartel for the Arabidopsis pex4 and pex6 mutant seeds and Dr. Markus Schmid for ideas on this project, especially for the design of the ΔZn-pex10. The skillful technical assistance of Ms. Silvia Dobler is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant Gi 154/12-1.

Abbreviations

- TAIL-PCR

thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR

- IBA

indole-3-butyric acid

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- PEX

peroxin.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0610402104/DC1.

References

- 1.Olsen LJ. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38:163–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somerville CR. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:20–24. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Somerville CR. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1986;37:467–507. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gietl C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1100:217–234. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90476-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wasternak C, House B. Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 2002;72:165–221. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(02)72070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zolman BK, Yoder A, Bartel B. Genetics. 2000;156:1323–1337. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.3.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zolman BK, Bartel B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1786–1791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304368101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zolman BK, Monroe-Augustus M, Silva ID, Bartel B. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3422–3435. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckert JH, Erdmann R. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;147:75–121. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mano S, Nishimura M. Vitam Horm. 2005;72:111–154. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)72004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wanders JA, Waterham HR. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:295–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumann U, Wanner G, Veenhuis M, Schmid M, Gietl C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9626–9631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633697100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparkes IA, Brandizzi F, Slocombe SP, El-Shami M, Hawes C, Baker A. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1809–1819. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.031252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J, Aguirre M, Peto C, Alonso J, Ecker J, Chory J. Science. 2002;297:405–409. doi: 10.1126/science.1073633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan J, Quan T, Orth T, Awai C, Chory J, Hu J. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:231–239. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.066811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Titus DE, Becker WM. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1288–1299. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sautter C. Planta. 1986;167:491–503. doi: 10.1007/BF00391225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimura M, Yamaguchu J, Mori H, Akazawa T, Yokota S. Plant Physiol. 1986;80:313–316. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.1.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi M, Totiyama K, Kondo M, Nishimura M. Plant Cell. 1998;10:183–195. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wanner G, Vigil EL, Theimer RR. Planta. 1982;156:314–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00397469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saiki RK, Gelford DH, Stoffel S, Scharf SJ, Higuchi R, Horn GT, Mullis KB, Ehrlich HA. Science. 1988;239:487–490. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneidereit J, Häusler RE, Fiene G, Kaiser WM, Weber APM. Plant J. 2006;45:206–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichtenthaler HK. Methods Enzymol. 1987;148:350–382. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Häusler RE, Bailey KJ, Lea PJ, Leegood RC. Planta. 1996;22:388–396. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tolbert NE, Yamazaki RK, Oeser A. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:5129–5136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sautter C, Hock B. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:1162–1168. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.4.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gietl C, Wimmer B, Adamec J, Kalousek F. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:863–871. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.3.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiber U, Bilger W. Progr Bot. 1992;54:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y-G, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Whittier RF. Plant J. 1995;8:457–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08030457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.