Abstract

During the recombination of variable (V) and joining (J) gene segments at the T cell receptor α locus, a VαJα joint resulting from primary rearrangement can be replaced by subsequent rounds of secondary rearrangement that use progressively more 5′ Vα segments and progressively more 3′ Jα segments. To understand the mechanisms that target secondary T cell receptor α recombination, we studied the behavior of a T cell receptor α allele (HYα) engineered to mimic a natural primary rearrangement of TRAV17 to Jα57. The introduced VαJα segment was shown to provide chromatin accessibility to Jα segments situated within several kilobases downstream and to suppress germ-line Jα promoter activity and accessibility at greater distances. As a consequence, the VαJα segment directed secondary recombination events to a subset of Jα segments immediately downstream from the primary rearrangement. The data provide the mechanistic basis for a model of primary and secondary T cell receptor α recombination in which recombination events progress in multiple small steps down the Jα array.

Keywords: chromatin, promoter, thymus, variable(diversity)joining [V(D)J] recombination

Mature αβ T lymphocytes develop in the thymus from immature cells known as CD4−CD8− double-negative (DN) thymocytes. During the DN stage of development, the Tcrb locus rearranges its variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments by the process of V(D)J recombination (1). Expression of a functional T cell receptor (TCR)β protein leads to the development of CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) thymocytes, which then rearrange the Tcra locus (2). Tcra locus rearrangement is unique in several respects. First, primary Tcra rearrangements use Jα segments at the 5′ end of the 65-kb Jα array (3–6). Second, primary rearrangements can be replaced by secondary rearrangements that use progressively more 3′ Jα segments until a selectable αβ TCR is generated (7–12). Third, rearrangement occurs on both alleles in a relatively synchronous manner without allelic exclusion (10, 13, 14). Rearrangement terminates by down-regulation of recombinase expression as a result of positive selection or by apoptosis if positive selection fails to occur (6, 15–17). Positive selection allows the development of CD4+CD8− or CD4−CD8+ single-positive thymocytes, which then exit the thymus to the circulation. Although much is known about primary rearrangements, little is known about the mechanisms that control secondary rearrangements.

Multiple regulatory elements are known to activate and control accessibility to the Jα array (composed of 61 Jα segments) in DP thymocytes. The Tcra enhancer (Eα) at the 3′ end of the Tcra locus was shown by gene targeting to control all Vα-to-Jα rearrangements and to maintain the Jα array in an accessible state in DP thymocytes (18, 19). However, Eα-dependent accessibility also requires the activation of germ-line promoters within the Jα array. The T early α (TEA) and Jα49 promoters were identified at the 5′ end of the Jα array and were shown to account for the majority of primary rearrangements (20, 21). Rearrangements in mice lacking both promoters were substantially reduced across the entire 5′ region, recovering to normal levels by Jα37 (21). Two models have been proposed to explain the targeting of primary and secondary rearrangements (6, 13, 20). The “developmental windows” model suggests that sequential activation of developmentally controlled promoters along the Jα array controls the progression of rearrangements across the locus during DP thymocyte development. The second model argues that promoters at the 5′ end of the Jα array provide the initial accessibility for primary rearrangement and that successively introduced Vα promoters direct secondary rearrangements to Jα segments that are progressively more 3′. This model downplays the importance of other developmentally controlled promoters within the Jα array.

We previously showed that there are weak promoter elements associated with Jα segments in the central and 3′ portions of the Jα array and that transcription from these promoters was substantially elevated in DP thymocytes of mice lacking both the TEA and Jα49 promoters (21). This increase in central and 3′ promoter activity correlated with an increase in histone H3 and histone H4 acetylation and with the retargeting of primary rearrangements to the central and 3′ Jα segments. These observations led us to propose the following mechanism for secondary rearrangement: once the TEA promoter is deleted by primary rearrangement, promoter elements located in the central and 3′ portions of the Jα array become activated and provide accessibility for secondary rearrangements to central and 3′ Jα segments.

Primary rearrangement replaces the TEA promoter with the promoter of a Vα segment. However, the role of the promoter of the rearranged Vα in Jα accessibility and in secondary rearrangements is not known. To test the role of the Vα promoter in directing secondary rearrangements, we took advantage of HY-I mice (11), which carry an engineered Tcra allele that simulates a natural primary rearrangement of a proximal Vα segment (TRAV17) to Jα57. We found that TRAV17 suppressed the activity of central promoter elements and focused the first wave of rearrangements to the portion of the Jα array immediately downstream from the Vα segment (Jα53 to Jα45). Based on these results, we have incorporated the role of Vα promoters into our previous model for secondary Tcra recombination (21), and we suggest that Vα promoters play an important role in directing secondary rearrangements to a small set of downstream Jα segments. By doing so, they ensure that rearrangements proceed along the Jα array in small steps to maximize the chances for positive selection.

Results

We assessed the role of the promoter of the rearranged Vα segment in controlling accessibility to downstream Jα segments by using the HY-I mouse model (11). The HY TCR recognizes a male-specific peptide in the context of H-2Db (22). In the HY-I model, the HY TCR is encoded by a VαJα joint inserted into the endogenous Tcra locus (HYα) and a randomly integrated Tcrb transgene (HYβtg). The HYα allele was generated by gene-targeted insertion of TRAV17 Jα57 in place of wild-type Jα57, followed by Cre-loxP-mediated deletion of the region between TRAV21/DV12 (in the proximal portion of the Vα array) and the insertion (11). Thus, it structurally mimics a normal primary VαJα rearranged allele (Fig. 1A). Previous data showed that on a nonpositively selecting background, the inserted HY VαJα joint was replaced by secondary Vα to Jα recombination in most DP cells (11). We introduced the HYα allele and an unrelated Tcrb transgene onto a recombinase-deficient (Rag2−/−) background to obtain HYα R×β mice. Hence, the TCR that is generated in thymocytes of HYα R×β mice is of unknown specificity. To assess whether thymocytes of HYα R×β were positively selected, we analyzed thymocyte populations by flow cytometry with antibodies specific for CD4, CD8, and TCRβ (data not shown). An abundant DP population but no single positive thymocytes were detected, implying a lack of positive selection. Thus, HYα R×β mice provide a highly enriched population of DP thymocytes to analyze Tcra locus structure and regulation.

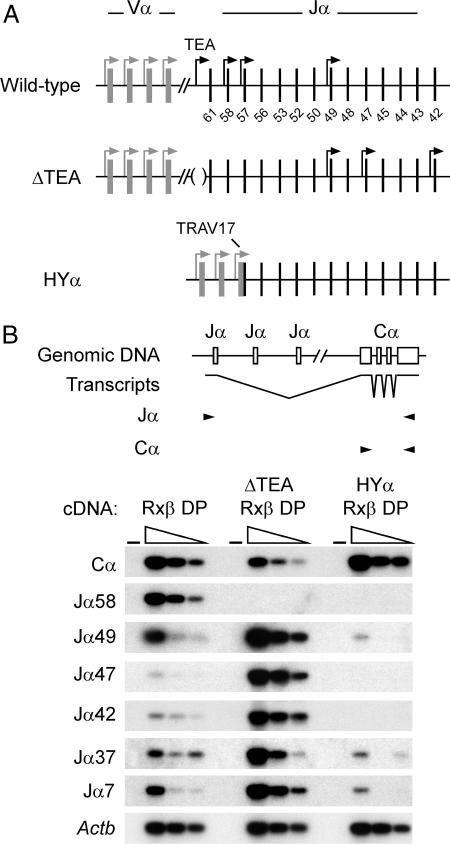

Fig. 1.

Tcra allele structure and germ-line transcription. (A) Schematic maps of the wild-type, ΔTEA, and HYα Tcra alleles are shown. The gray rectangles identify Vα segments, and black vertical lines represent Jα segments (numbered). Bent arrows identify the locations of active promoters. The diagram depicts changes in promoter activity on the ΔTEA and HYα alleles. (B) RT-PCR analysis of Tcra transcripts. The structure of spliced Jα transcripts and the PCR strategies used to detect individual Jα transcripts and total Cα-containing transcripts are presented. PCR primers are indicated by arrowheads. Serial 3-fold dilutions of cDNA prepared from R×β, ΔTEA R×β, and HYα R×β thymocytes were analyzed by RT-PCR to detect Jα transcripts, total Cα-containing transcripts, or β-actin (Actb) transcripts. (−) indicates a control PCR lacking cDNA. PCRs were analyzed by Southern blotting with Cα or Actb probes. Because of variations in PCR efficiency, PCR cycle number, and exposure time, the figure should not be taken to indicate quantitative relationships among the different transcripts; however, for any individual transcript, quantitative comparisons are valid among the different thymus RNA samples.

We compared the Tcra loci of thymocytes from R×β, ΔTEA R×β, and HYα R×β mice. The Tcra locus in R×β thymocytes is unmanipulated and in germ-line configuration. By comparing the ΔTEA R×β Tcra locus with that of R×β, we could assess the effect of deleting the TEA promoter, which would naturally occur as a consequence of primary Vα to Jα rearrangement. The HYα R×β Tcra locus lacks the TEA promoter as well, but in addition it includes the promoter of the rearranged VαJα. Therefore, a comparison of HYα R×β with the ΔTEA R×β allowed us to evaluate selectively the influence of the Vα promoter newly introduced by primary Vα to Jα rearrangement (Fig. 1A).

To assess the level of promoter activation across the Jα array, we prepared cDNA from total thymocytes of R×β, ΔTEA R×β, and HYα R×β mice, and we measured the abundance of spliced Tcra transcripts by RT-PCR using different Jα primers paired with a common constant (C)α primer. In R×β thymocytes, germ-line transcripts were previously reported to initiate at a high frequency from several sites in the 5′ portion of the Jα locus (TEA, Jα58, Jα57, and Jα49) but at low frequency from sites further downstream (Jα47, Jα42, and Jα37) (21). TEA promoter deletion was shown to result in an overall reduction in germ-line transcripts and complete loss of transcripts initiating at TEA, Jα58, and Jα57 but increases in transcripts initiating at downstream sites. Consistent with this picture, the present analysis of ΔTEA R×β mice revealed a loss of Jα58 transcripts but substantial increases in the frequencies of transcripts initiating at Jα49, Jα47, Jα42, Jα37, and Jα7 compared with R×β (Fig. 1B). Introduction of TRAV17 in HYα R×β thymocytes reversed the effect of deleting the TEA promoter: total Tcra transcripts (measured with a pair of Cα primers) were up-regulated to a level that was comparable with that in R×β thymocytes, whereas transcripts from all Jα promoter elements tested were potently suppressed. This result implies that the TRAV17 promoter accounts for almost all transcription across the Jα array and that it suppresses downstream germ-line promoter elements even more efficiently than did TEA. Recent studies indicate that promoter suppression by TEA occurs through transcriptional interference (23); promoter suppression by TRAV17 is likely to occur through a similar mechanism. That suppression by TRAV17 is more potent than by TEA may reflect the fact that TRAV17 is 5 kb closer to downstream promoters than is TEA, resulting in higher levels of suppressive readthrough transcription at the downstream sites (23). We conclude that the introduced Vα promoter represents the only strong promoter in the Jα array after primary Vα to Jα recombination.

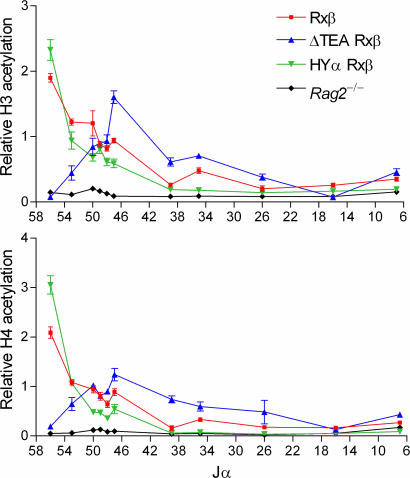

It has been shown for various immunoglobin and TCR loci that accessibility for V(D)J recombination correlates with the elevated acetylation of histones H3 and H4 (24). Therefore, to evaluate the influence of upstream promoters on chromatin structure across the Jα array, mononucleosomes were prepared from Rag2−/−, R×β, ΔTEA R×β, and HYα R×β mice and immunoprecipitated with antibodies directed to diacetylated H3 and tetraacetylated H4. DNA was recovered from the immunoprecipitated material and used to quantify acetylation at Jα segments by real-time PCR (Fig. 2). As reported previously (21, 25), acetylation was high in R×β at the most 5′ Jα segments, and it declined gradually toward the 3′ end of the Jα array. As a negative control, acetylation in DN thymocytes of Rag2−/− mice was very low across all Jα segments. Consistent with a previous study that analyzed an allele with a distinct and larger deletion of the TEA promoter region (25), acetylation in ΔTEA R×β was very low across the 5′ portion of the Jα array, but it recovered gradually, and it was elevated above the level in R×β at Jα47 and several sites further 3′ (Fig. 2). Increased acetylation in the central region between Jα49 and Jα26 correlated with the increases in germ-line transcripts associated with central Jα segments in ΔTEA R×β thymocytes (Fig. 1B). Significantly, analysis of HYα R×β DP thymocytes showed that introduction of TRAV17 reversed the effects of TEA promoter deletion: acetylation of 5′ Jα segments was restored, whereas acetylation of central and 3′ Jα segments was suppressed (Fig. 2). In fact, H3 acetylation in HYα R×β was higher than R×β at Jα56 and even lower at sites further 3′, paralleling the potent suppression of downstream promoters on the HYα allele (Fig. 1B). Essentially identical results were obtained for H4 acetylation (Fig. 2). We conclude that the introduced TRAV17 very potently focuses accessible chromatin structure to a small portion of the Jα array lying immediately downstream.

Fig. 2.

Tcra allele histone modifications. Histone H3 and H4 acetylation was analyzed by immunoprecipitation of chromatin prepared from thymocytes of R×β, ΔTEA R×β, HYα R×β, and Rag2−/− mice. Sites associated with Jα segments (numbered) were analyzed. Bound and input fractions were quantified using real-time PCR, and ratios of bound/input were normalized to that for β2-microglobulin in each sample. The data shown are representative of two experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of triplicate PCRs.

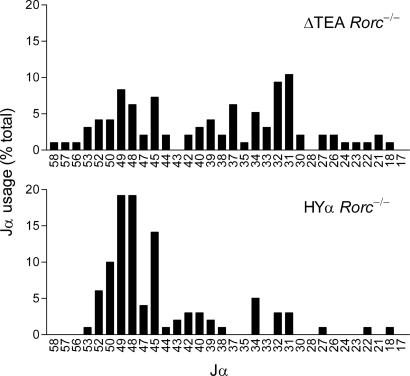

To understand the influence of TRAV17 on secondary rearrangements, we bred mice to introduce ΔTEA and HYα alleles onto a genetic background deficient for transcription factor RORγ (Rorc−/−). The orphan nuclear receptor RORγ is expressed in its highest amount in DP thymocytes and controls DP thymocyte survival by regulating the expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL (26). In the absence of RORγ, DP thymocytes are short-lived, and Jα usage is limited to the 5′ portion of the Jα array, reflecting one or a very few rounds of rearrangement (6). We amplified cDNA from ΔTEA Rorc−/− and HYα Rorc−/− thymocytes by PCR using TRAV12 (Vα8) and Cα primers (Fig. 3). Cloned PCR products were then sequenced to identify the distribution of Jα segments used in the early rearrangements on these alleles. We previously identified two peaks of Jα usage in Rorc−/− thymocytes, one immediately downstream from TEA that involves Jα58 and Jα57 and a second centered around Jα49 that involves Jα52-Jα45 (21). We showed that Jα49 promoter deletion eliminated usage of Jα52–Jα45 and that deletion of both the TEA and Jα49 promoters eliminated usage of both sets of Jα segments and retargeted rearrangements to the central Jα segments. Consistent with these results, analysis of ΔTEA Rorc−/− thymocytes indicated that deletion of the TEA promoter alone drastically reduced usage of Jα58 and Jα57 but did not substantially affect Jα52–Jα45 usage (Fig. 3). Moreover, TEA promoter deletion led to a large increase in usage of central Jα segments spanning the region from Jα42 to Jα30. This increase in central Jα usage correlates with and is likely a consequence of the increased activity of central Jα promoters. In sharp contrast, analysis of HYα Rorc−/− mice revealed Jα usage to be largely restricted to the Jα52–Jα45 interval (73% vs. 32% in ΔTEA Rorc−/−) with targeting to the central Jα segments substantially suppressed (23% vs. 51% in ΔTEA Rorc−/−). We conclude that the introduced TRAV17 focuses rearrangements to a limited number of Jα segments immediately downstream from TRAV17, presumably because the TRAV17 promoter suppresses central promoter elements and limits the region of chromatin modifications.

Fig. 3.

Targeting of secondary Vα to Jα recombination on the HYα allele. TRAV12 (Vα8) to Cα RT-PCR products obtained from thymocytes of 3- to 6-week-old ΔTEA Rorc−/− and HYα Rorc−/− mice were cloned and sequenced to evaluate Jα usage. The fraction of clones using particular Jα segments (numbered) is plotted. Numbers of clones analyzed for ΔTEA Rorc−/− and HYα Rorc−/− were 96 and 99, respectively. Because the TRAV12 primer detects multiple dispersed TRAV12 family members, TRAV12 rearrangements are relatively unbiased with respect to Jα usage.

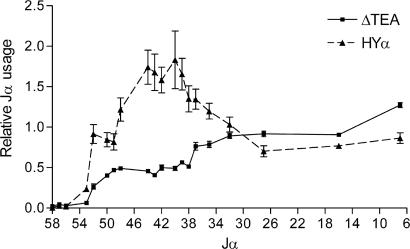

As a separate measure of the ability of the introduced TRAV17 promoter to influence the Jα repertoire, we compared the Jα repertoire of HYα thymocytes with that of ΔTEA thymocytes on an otherwise wild-type background that allowed for multiple rounds of Vα to Jα rearrangement (Fig. 4). We prepared cDNA from HYα and ΔTEA thymocytes and amplified them by using TRAV12 and Cα primers. We then fractionated PCR products on agarose gels, transferred them to nylon filters, and evaluated Jα usage by hybridization with Jα-specific oligonucleotide probes. As described (20, 21), the Jα repertoire in ΔTEA mice was suppressed across the 5′ region, with recovery to wild-type levels by Jα37. In contrast, Jα usage in HYα mice was at wild-type levels or above from Jα52 to Jα32. Thus, the introduced TRAV17 promoter has a dramatic effect on both the initial round of Vα to Jα rearrangements and the steady-state thymic Jα repertoire.

Fig. 4.

Thymic Jα repertoires of mice carrying the HYα allele. TRAV12 (Vα8) to Cα and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) RT-PCR products obtained from thymocytes of 4- to 5-week-old wild-type, ΔTEA, and HYα mice were fractionated on agarose gels and immobilized to nylon filters. Jα usage was evaluated by hybridization with 32P-labeled Jα and G6PD oligonucleotide probes and was expressed as (variant allele Jα/G6PD)/(wild-type allele Jα/G6PD). Results represent the mean ± SEM of three or four determinations.

Discussion

We have shown previously (21) that deleting both the TEA and Jα49 promoters from the Jα array activates promoter elements associated with downstream Jα segments. We attributed that activation specifically to the removal of TEA and confirmed this in the present work by analysis of mice lacking the TEA promoter only. We hypothesized that removal of the TEA promoter by primary rearrangement in wild-type thymocytes might also activate downstream promoter elements and that such activation might provide accessibility for secondary rearrangements. However, the impact of the promoter of the rearranged Vα was not accounted for in that model. Here, we took advantage of HY-I mice to evaluate how the introduced Vα promoter regulates Jα chromatin structure and the targeting of Vα to Jα recombination events. Previous work with this model indicated that the inserted HY VαJα joint could be replaced by secondary rearrangements in the absence of positive selection (11). However, only a small set of rearrangements were structurally characterized, and there was no means of restricting the analysis to the initial round of rearrangement. Moreover, chromatin structure and promoter activity were not addressed in that study.

Our comparison of ΔTEA with HYα alleles clearly implicated the rearranged VαJα in the regulation of Jα accessibility and recombination. First, the rearranged VαJα induced elevated acetylation of histones H3 and H4 over several kilobases immediately downstream. Second, the rearranged VαJα suppressed the Jα49 and additional central Jα promoter elements even more potently than did TEA. Our analysis of HYα Rorc−/− mice indicated that these influences had the effect of focusing secondary rearrangements to a limited number of Jα segments immediately downstream from the rearranged VαJα. Assuming that subsequently introduced VαJα rearrangements would behave similarly, rearrangements would then proceed along the locus in a series of small steps (i.e., according to the “local service” model; ref. 6) (Fig. 5). In this view, an important function of incoming Vα segments is continually to suppress downstream Jα promoters to prevent disorganized and uncoordinated secondary rearrangements that would proceed in large jumps down the Jα array. This mechanism ensures efficient use of Jα segments and would maximize the chances for positive selection.

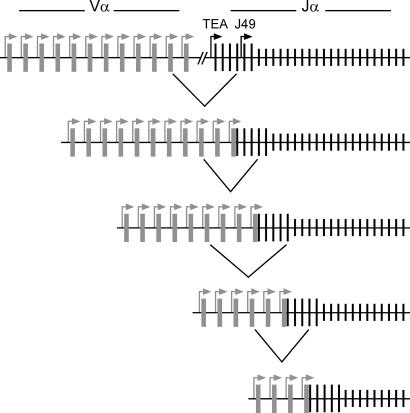

Fig. 5.

Model for primary and secondary Vα to Jα recombination. The diagram depicts Vα segments as gray rectangles, accessible Jα segments as long black vertical lines, and inaccessible Jα segments as short black vertical lines. Promoters are depicted as bent arrows. In the model, primary Vα to Jα rearrangement is directed to a set of Jα segments made accessible by the germ-line TEA and Jα49 promoters. Secondary Vα to Jα rearrangements are directed to discrete sets of Jα segments made accessible by successively introduced Vα promoters. Rearrangements would progress down the Jα array in multiple small steps.

We assume that the ability of the introduced VαJα to target secondary rearrangements in this fashion depends on the promoter of the rearranged Vα. Based on the analysis of secondary rearrangements in HYα Rorc−/− thymocytes, the TRAV17 promoter appeared to target rearrangements to the region spanning Jα52–Jα45, which corresponds closely to the region that we had previously shown to be targeted by the Jα49 promoter (21). Nevertheless, we think that the TRAV17 promoter and not the Jα49 or other Jα promoters was involved in targeting secondary rearrangements in this instance because the Jα49 and downstream promoters were efficiently suppressed by the TRAV17 promoter. Recent studies reveal that the ability of the TEA promoter to create accessibility over downstream Jα segments depends directly on transcriptional elongation through those Jα segments (23). Accessibility is a presumed consequence of transcription-dependent chromatin modifications that extend for several kilobases downstream from the promoter. Further downstream, transcription not only fails to create accessibility, but it also suppresses downstream promoters through transcriptional interference. We believe that the same phenomena occur as a consequence of TRAV17 promoter-dependent transcription.

Surprisingly, we were unable to detect secondary rearrangement of Jα56, the first functional Jα downstream from the TRAV17 Jα57 joint on the HYα allele. This failure cannot reflect an intrinsic defect in the ability of Jα56 to rearrange because the sequence of the Jα56 recombination signal sequence (RSS) diverges little from the RSS consensus and Jα56 usage is readily detected on wild-type alleles (Fig. 4). Moreover, it also seems unlikely to be the result of an accessibility defect because H3 and H4 acetylation were both very high at this site on the HYα allele (Fig. 2). We checked for the possibility of inactivating mutations that might have been introduced during the targeting of the HYα VαJα joint, but we found none (data not shown). In addition, because HYα was previously shown to be expressed prematurely in DN thymocytes (11), we tested whether secondary rearrangement to Jα56 occurred in DN rather than DP thymocytes. However, no such evidence was obtained (data not shown). Thus, the absence of Jα56 usage remains unexplained.

The suppression of central Jα promoters by both TEA and TRAV17 raises questions as to whether these cryptic central promoters are ever substantially activated in vivo and whether there are circumstances in which they do play a role in targeting Vα to Jα recombination events. One possibility is that a relatively weak Vα promoter may be able to provide accessibility to its own RSS at a distance of 400–500 bp, but after VαJα rearrangement it may be unable to provide accessibility to Jα RSSs several kilobases downstream. If such a promoter also failed to suppress central Jα promoters, those promoters could provide a fail-safe mechanism to allow for continued rearrangement events that would rescue the allele for further use. In this regard, we previously identified by PCR elevated levels of spliced transcripts initiating upstream from Jα47, Jα42, and Jα37 on wild-type alleles in thymocytes of Rorc−/− mice (21). Because these alleles should carry heterogeneous VαJα rearrangements involving primarily 5′ Jα segments, the results are consistent with the possibility that central promoters may be active on at least a subset of rearranged alleles. However, the results should be interpreted with some caution because the PCR approach leaves ambiguity regarding the true sites of transcript initiation on the heterogeneous genomic templates. By contrast, the current results for the HYα allele are unambiguous. We suggest that the behavior of TRAV17 is likely to be representative of the majority of Vα segments which, by providing local activation and long-distance suppression, would enforce the stepwise propagation of secondary Vα to Jα recombination events along the Jα array. Nevertheless, the generality of this conclusion may only be confirmed by analysis of homogeneously rearranged alleles that test additional Vα gene segments.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Strains.

Mice homozygous for the ΔTEA allele were described in ref. 21. Mice homozygous for the HYα allele (11) were kindly provided by Barry Sleckman (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). The two alleles were each bred to homozygosity on both the Rorc−/− (26) and Rag2−/− Tcrb transgene (R×β) (27) backgrounds. Rag2−/− mice (28) were on a 129 background, and all Tcra alleles examined were of 129 origin. All mice were used in accordance with protocols approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Durham, NC).

RT-PCR Analysis of Tcra Transcripts.

Thymocyte RNA was converted to cDNA and analyzed by RT-PCR as described in ref. 21. The Jα primers were positioned immediately upstream from the respective gene segments: Jα58 (5′-TGCAAAGCCCTTCAGTGCAGT-3′), Jα49 (5′-GGGAAAGGAACAAGTTTGAC-3′), Jα47 (5′-GTCACAGGAGTTTGAGGCTGT-3′), Jα42 (5′-CCCAAATGACTGTGAATTCTGG-3′), Jα37 (5′-AAAGTGCAGCATTGGGGTGTAA-3′), and Jα7 (5′-ACAGACTTACTTTGGGGAAG-3′).

RT-PCR Analysis of Jα Usage.

RT-PCR, blotting, probing, and quantification of Jα usage were performed as described in ref. 21 with the exception that Jα signals were normalized to G6PD rather than to Cα. Primers used for G6PD PCR were 5′-TTGTAGGTACCCTCGTACTG-3′ and 5′-TCCTGCAGATGTTGTGTCTG-3′. The G6PD probe was 5′-TGCCAGGCTTCTTGGTCATC-3′. Hybridization and washing were both at 50°C.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation.

Mononucleosomes were prepared and immunoprecipitated as described in refs. 19 and 21, with additional primers 5′-CGTTGAAGCTTCAGGGGAGGT-3′ and 5′-ACGGTTCCTTGACCAAAAGTCAGC-3′ for Jα56, and 5′-TCCTGAGTTGTAGTGTTGCG-3′ and 5′-ACAGATACTCTGGTGCCAAG-3′ for Jα26.

Acknowledgments

We thank Iratxe Abarrategui and Juan Carabana for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM41052 (to M.S.K.).

Abbreviations

- C

constant

- D

diversity

- DN

double negative

- DP

double positive

- Eα

Tcra enhancer

- G6PD

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- J

joining

- R×β

Rag2−/− × Tcrb transgene

- RSS

recombination signal sequence

- TCR

T cell receptor

- TEA

T early α

- V

variable.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

References

- 1.Bassing CH, Swat W, Alt FW. Cell. 2002;109:S45–S55. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krangel MS, Carabana J, Abarrategui I, Schlimgen R, Hawwari A. Immunol Rev. 2004;200:224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson SD, Pelkonen J, Hurwitz JL. J Immunol. 1990;145:2347–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrie HT, Livak F, Burtrum D, Mazel S. J Exp Med. 1995;182:121–127. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yannoutsos N, Wilson P, Yu W, Chen HT, Nussenzweig A, Petrie H, Nussenzweig MC. J Exp Med. 2001;194:471–480. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo J, Hawwari A, Li H, Sun Z, Mahanta SK, Littman DR, Krangel MS, He YW. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:469–476. doi: 10.1038/ni791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marolleau J-P, Fondell JD, Malissen M, Trucy J, Barbier E, Marcu KB, Cazenave P-A, Primi D. Cell. 1988;55:291–300. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrie HT, Livak F, Schatz DG, Strasser A, Crispe IN, Shortman K. J Exp Med. 1993;178:615–622. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang F, Huang C-Y, Kanagawa O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11834–11839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C-Y, Kanagawa O. J Immunol. 2001;166:2597–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buch T, Rieux-Laucat F, Forster I, Rajewsky K. Immunity. 2002;16:707–718. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00312-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang CY, Sleckman BP, Kanagawa O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14356–14361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505564102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mauvieux L, Villey I, de Villartay J-P. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2080–2086. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2080::aid-immu2080>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davodeau F, Difilippantonio M, Roldan E, Malissen M, Casanova JL, Couedel C, Morcet JF, Merkenschlager M, Nussenzweig A, Bonneville M, et al. EMBO J. 2001;20:4717–4729. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turka L, Schatz DG, Oettinger MA, Chun JJM, Gorka C, Lee K, McCormack WT, Thompson C. Science. 1991;253:778–781. doi: 10.1126/science.1831564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borgulya P, Kishi H, Uematsu Y, von Boehmer H. Cell. 1992;69:529–537. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90453-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandle D, Muller C, Rulicke T, Hengartner H, Pircher H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9529–9533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sleckman BP, Bardon CG, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Alt FW. Immunity. 1997;7:505–515. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMurry MT, Krangel MS. Science. 2000;287:495–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villey I, Caillol D, Selz F, Ferrier P, de Villartay J-P. Immunity. 1996;5:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawwari A, Bock C, Krangel MS. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:481–489. doi: 10.1038/ni1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uematsu Y, Ryser S, Dembic Z, Borgulya P, Krimpenfort P, Berns A, von Boehmer H, Steinmetz M. Cell. 1988;52:831–841. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abarrategui I, Krangel MS. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krangel MS. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:624–630. doi: 10.1038/ni0703-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauvieux L, Villey I, de Villartay J-P. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2216–2222. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Z, Unutmaz D, Zou YR, Sunshine MJ, Pierani A, Brenner-Morton S, Mebius RE, Littman DR. Science. 2000;288:2369–2373. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinkai Y, Koyasu S, Nakayama K-I, Murphy KM, Loh DY, Reinherz EL, Alt FW. Science. 1993;259:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.8430336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam K-P, Oltz EM, Stewart VE, Mendelsohn M, Charron J, Datta M, Young F, Stall AM, et al. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]