Abstract

The biology of Candida albicans, including dimorphism and virulence, is significantly influenced by environmental pH. The response to ambient pH includes the pH-conditional expression of several genes, which is directly or indirectly regulated by Rim101p. Rim101p is homologous to PacC, a transcription factor that regulates pH-conditional gene expression in Aspergillus nidulans. PacC binds 5′-GCCARG-3′ sequences upstream of pH-responsive genes and either activates or represses transcription. The absence of pacC consensus binding sites upstream of PHR1, a RIM101-dependent, alkaline pH-induced gene of C. albicans, suggested either that PHR1 is indirectly regulated by Rim101p or that the binding specificity of Rim101p is different. In vitro binding studies demonstrated that Rim101p strongly bound two regions upstream of PHR1 that were only weakly bound by PacC. Deletion analysis and site-specific mutagenesis demonstrated that both sites were functionally significant, mutation of either site reduced RIM101-dependent induction, and expression was abolished in the double mutant. Furthermore, oligonucleotides containing these sites conferred pH-conditional expression when inserted upstream of a reporter gene. The consensus sequence of these sites, 5′-CCAAGAAA-3′, was identical to the binding recognition sequence identified by in vitro selection of Rim101p binding oligonucleotides from a random pool. The functional significance of this binding sequence was reinforced by its observed presence upstream of a number of newly identified pH-conditional genes. We conclude that Rim101p acts as a transcription factor and directly regulates pH-conditional gene expression but has a binding specificity different from that of PacC.

Microorganisms have a limited capacity to control their external environment and instead must often adapt to changes in their surroundings. Ambient pH profoundly affects the biology of fungi, influencing the metabolism, meiotic processes, morphological development, and virulence of plant and animal pathogens (9). These responses derive, in part, from alterations in the expression of genes, many of which encode cell surface or secreted proteins that are directly exposed to the environment (9).

An apparently conserved signal pathway mediates responses to ambient pH. As elaborated in Aspergillus nidulans, the pathway consists of several pal genes of uncertain function, which effect the pH-conditional activation of the transcription factor PacC (16). Activation occurs at alkaline pH and requires two sequential proteolytic steps that remove the C-terminal two-thirds of the protein (10). The truncated amino terminus localizes to the nucleus, where it induces alkaline pH-expressed genes and represses acid pH-expressed genes (28, 43). PacC directly controls transcription by binding upstream of the affected genes (13, 15). This interaction occurs through a domain that contains three zinc fingers and that selectively recognizes the sequence 5′-GCCARG-3′ (17).

Elements of this pathway have been described for a range of fungi (9). Orthologs of PacC, variously named PaC or Rim101p, have been reported for eight ascomycetes and, except for closely related species, sequence similarity is confined almost entirely to the zinc finger domain (8, 25, 26, 36, 37, 39, 41, 43). In vitro DNA binding has been demonstrated for PacC from three filamentous fungi, and each recognizes the consensus sequence 5′-GCCARG-3′ (39, 42, 43).

Mutational analyses have shown the functional importance of upstream 5′-GCCARG-3′ sequences in the pH-conditional expression of several genes of Aspergillus spp.; these include ipnA, encoding isopenicillin N synthase (15), gabA, which encodes a transporter of γ-aminobutyric acid (13), and the polyketide synthase gene pksA (12). Potential PacC binding sites have also been implicated in the expression of isopenicillin N synthase of Acremonium chrysogenum (39) and the Yarrowia lipolytica protease gene XPR2 (27) and in the repression of NRG1, SMP1, and RIM8 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (24). Although a PacC binding site may be necessary, it may not be sufficient to confer pH-conditional expression (24, 27).

Analogous to A. nidulans PacC, Rim101p/Prr2p of the human pathogen Candida albicans acts as a positive regulator of alkaline pH-expressed genes and a negative regulator of acid pH-expressed genes (8, 15, 20, 36). It is required for proper morphological development and virulence (7, 8, 36). Genetic evidence suggests that, like PacC, Rim101p is activated by proteolytic removal of the carboxy terminus (2, 8, 35). In this study, we demonstrate that Rim101p is a DNA binding protein and that, unlike Saccharomyces cerevisiae but like A. nidulans, it activates transcription of the alkaline pH-expressed gene PHR1 through its binding upstream. A Rim101p binding site was sufficient to confer pH-conditional expression to an artificial promoter, demonstrating that Rim101p can independently activate expression. However, the DNA sequence recognized by Rim101p is not the same as that recognized by PacC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The C. albicans strains used are listed in Table 1. Strains were cultured at 30°C on YPD (2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone); YNB (2% glucose, 0.67% Difco yeast nitrogen base); or medium 199 containing Earle's salts and glutamine but lacking sodium bicarbonate (Gibco-BRL), supplemented with 150 mM HEPES, and adjusted to pH 4.0 or 7.5. S. cerevisiae strain LL-20 (34) was cultured at 30°C on YPD. A. nidulans ATCC 26454 was maintained on minimal medium (33) and cultured in alkaline penicillin production broth (14) for RNA isolation.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used in this work

| Strain | Parent | Genotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAI4 | iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | 36 | |

| CAI12 | CAI4 | iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/IRO1 URA3 | 36 |

| CAR2 | CAR16 | rim101Δ::hisG/rim101Δ::hisG::URA3::hisG iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | 36 |

| CAR26 | CAR2 | rim101Δ::hisG/rim101Δ::hisG iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | 36 |

| CAR2-U1 | CAR26 | rim101Δ::hisG/rim101Δ::hisG iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/IRO1 URA3 | This work |

| TAN3 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(952)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| TAN5 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(707)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| TAN7 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(489)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| TAN9 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(262)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| TAN3X1 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(952,1Xbal)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| TAN3X2 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(952,2Xbal)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| TAN3X12 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(952,1,2Xbal)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL0 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-P0-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL1 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(1BS)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL2 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(2BS)-GFP-iro1 ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL3 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(3BS)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL4 | CAI4 | IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(3BS)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL5 | CAR26 | rim101Δ::hisG/rim101Δ::hisG IRO1 URA3-P0-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL6 | CAR26 | rim101Δ::hisG/rim101Δ::hisG IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(1BS)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL7 | CAR26 | rim101Δ::hisG/rim101Δ::hisG IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(2BS)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL8 | CAR26 | rim101Δ::hisG/rim101Δ::hisG IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(3BS)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

| RAL9 | CAR26 | rim101Δ::hisG/rim101Δ::hisG IRO1 URA3-PPHR1(0BS)-GFP-iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434/iro1-ura3Δ::λimm434 | This work |

GFP, GFP gene. PPHR1 designations indicate the following (examples of each type are explained): PPHR1(952), −952 to −8 PHR1 fragment; PPHR1(952, 1XaI), −952 to −8 PHR1 fragment with mutations at positions −825 and −823; P0, no Rim101p binding sequence; and PPHR1(1BS), BS-825 fragment.

Production of GST fusion proteins.

The zinc finger domain of Rim101p was expressed as a fusion protein appended to the C terminus of glutathione S-transferase (GST). DNA encoding the zinc finger domain was amplified by PCR with primers 5′-TGAATTCAACCATCACAGCAATACCAC-3′ and 5′-TGAATTCAGTTTGCTCGCTTGTTGG-3′ and plasmid pARA1 (36) as a template. The 522-bp PCR product encoded amino acids Q159 through N331, with an adjacent translational stop codon. This product was cleaved at the EcoRI sites designed into the primer ends and cloned into the EcoRI site of plasmid pGEX-2T (Pharmacia). The fidelity and orientation of the cloned product were verified by nucleotide sequencing.

An analogous GST fusion protein containing the zinc finger domain of A. nidulans PacC was created essentially as described by Tilburn et al. (43). Total RNA was extracted from cells grown in alkaline medium to enhance pacC expression (14) and used as a template for cDNA synthesis. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) with the oligonucleotide 5′-ATAGTGCGCAGCAGCATAGCC-3′ as a primer. Double-stranded cDNA was produced by PCR amplification with the preceding oligonucleotide and oligonucleotide 5′-CGCTGCGCAGGTTACAACTGTC-3′ as primers. The 498-bp PCR product, encoding amino acids Q30 to A195, was digested with FspI, and the resulting blunt-ended product was cloned into the SmaI site of pGEX-2T. The fidelity and orientation of the cloned product were verified by nucleotide sequencing.

Fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE) (Novagen). A single colony was inoculated into Luria broth (LB) with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and grown overnight at 37°C. The culture was diluted 1:100 into fresh LB-ampicillin and grown at 37°C until the optical density at 595 nm (OD595) reached 0.6. Expression was induced by the addition of 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and incubation was continued for 3 h. Cells were recovered by centrifugation, washed with modified phosphate-buffered saline (637 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, 1.4 mM KH2PO4) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and 200 μM 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride · HCl (AEBSF), and suspended in the same buffer. Cells were lysed in an Aminco pressure cell, and the lysate was made 1% in Triton X-100. Following clarification by centrifugation, the supernatant was mixed with glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia) for 2 h at 4°C with rotation. Sepharose beads were collected by centrifugation and washed two times with the above-described buffer. Bound protein was eluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-0.5 M NaCl containing 30 mM glutathione. Protein in the eluate was quantified by using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Native GST expressed from pGEX-2T was purified in parallel as a control.

EMSAs.

For electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), GST fusion protein and DNA probe were mixed in 20 μl of H50 buffer (25.0 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 0.1 mM EDTA, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 50.0 mM KCl, 1.0 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 20.0% [wt/vol] glycerol, 0.2 mM AEBSF, 1 μl of protease inhibitor cocktail/ml) (43) containing 1.6 μg of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC) (Pharmacia) and incubated for 30 min on ice. The reactions were fractionated in 4 or 8% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 4°C. The gels were dried, and DNA banding was detected by either autoradiography or phosphorimaging. Phosphorimages were quantified by using ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics) or the public domain program NIH Image (developed at the National Institutes of Health and available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

DNA probes were generated by PCR amplification of the following regions upstream of PHR1: nucleotides −952 to −707, −864 to −707, and −707 to −489. Nucleotide positions are expressed relative to the initiating ATG codon of PHR1. Additional probes were made by extension of end-labeled primers with the Klenow polymerase (Gibco-BRL). Oligonucleotide primers were denatured for 5 min at 95°C, cooled on ice, and annealed with templates for 30 min at 37°C. Extension was performed for 30 min at room temperature following the manufacturer's instructions, and the reaction products were purified by using Micro-SELECT spin columns (5 Prime-3 Prime, Inc.). The template oligonucleotides BS-825 (5′-TAAAAAAAAAACCAAGAAAAATATTCCATCTTTATAACC-3′) and BS-825X (5′-TAAAAAAAAAATCTAGAAAAATATTCCATCTTTATAACC-3′) were primed with the 14-mer 5′-GGTTATAAAGATGG-3′. These templates encompass nucleotides −836 to −798 of PHR1. BS-825 reproduces the wild-type sequence. BS-825X incorporates transition and transversion mutations at positions −825 and −823, respectively. The template oligonucleotides BS-516 (5′-TGAAAATAAAACCAAGAAATTTTATTGAATATTTCAATCC-3′) and BS-516X (5′-TGAAAATAAAATCTAGAAATTTTATTGAATATTTCAATCC-3′) were primed with 5′-GGATTGAAATATTC-3′. BS-516 parallels the wild-type sequence between nucleotides −527 and −488, while BS-516X contains mutations at positions −516 and −514. The template oligonucleotide BS-934 (5′-ATGGCATTCACCTAGAAACTAATCCAGAACCAATTAAGC-3′), which encompasses nucleotides −934 and −896 of the wild-type sequence, was primed with the 16-mer 5′-GCTTAATTGGTTCTGG-3′. An oligonucleotide containing a native PacC binding site, ipnA2, was prepared by annealing complementary oligonucleotides as described previously (15). All probes were end labeled by using T4 kinase and [γ-32P]dATP.

CAST determination of DNA sequences recognized by Rim101p.

Cyclic amplification and selection of targets (CAST) (44) was performed as described by Aoki et al. (1) with the following modifications. The pool of randomized oligonucleotides [AGACGGATCCATTGCA(N)20CTGTAGGAATTCGGA] was made double stranded by extension of the primer 5′-TCCGAATTCCTACAG-3′ with Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The 100-μl reaction mixture contained 5 U of Taq polymerase, 15 μg of randomized oligonucleotides, and 0.9 nmol of primer. Samples were denatured for 3 min at 94°C, annealed for 45 s at 52°C, and incubated for 30 min at 72°C. Reaction products were ethanol precipitated and dissolved in 21 μl of H2O. The double-stranded oligonucleotides were mixed with 45 μg of purified GST-Rim101p fusion protein in 50 μl of H50 buffer containing l.6 μg of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC). After 1 h on ice, 100 μl of a 50% slurry of glutathione-Sepharose 4B equilibrated with H50 buffer was added, and the mixture was incubated with rotation at 4°C for 2 h. The mixture was centrifuged, and the pellet was washed twice with H50 buffer and suspended in 50 μl of water. Twenty microliters of this suspension was added to a 50-μl PCR mixture containing primers complementary to the fixed end sequences, and the bound DNA was amplified by 13 cycles of PCR consisting of 60 s at 94°C, 45 s at 51°C, and 45 s at 72°C. Twenty microliters of the PCR product was used in the next CAST cycle. After the sixth cycle of selection, bound DNA was amplified by 33 cycles of PCR. The final amplification products were desalted by using a Sephadex Midi-SELECT G-25 spin column, and the eluted DNA was cloned into pTOPO-RT (Invitrogen). Two independent CAST selections were performed. The cloned DNA was sequenced, and the insert sequences were analyzed for conserved blocks by using a Gibbs sampling strategy as implemented in the program MACAW (40).

Plasmid and strain constructions.

Plasmids containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene flanked upstream by various promoter sequences and downstream by the terminator region of PHR1 were constructed in the following manner. The PHR1 terminator region, a 481-bp BstYI-SpeI fragment encompassing nucleotides +1782 to +1962, was cloned into the BglII and SpeI sites of LITMUS 28 (NEB), creating plasmid pLT. Various regions upstream of PHR1 were amplified by PCR with forward and reverse primers having NcoI and HindIII sites incorporated at the 5′ ends, respectively. The amplified fragments, designated N3, N5, N7, and N9, encompassed nucleotides −8 to −952, −8 to −707, −8 to −489, and −8 to −262, respectively. These were cloned into the NcoI and HindIII sites of pLT, producing plasmids pLTN3, pLTN5, pLTN7, and pLTN9. These were digested with HindIII and PstI and ligated with a HindIII-PstI fragment containing the GFP gene obtained from yEGFP (5), generating the series pLGTN3, pLGTN5, pLGTN7, and pLGTN9. The AgeI-SpeI fragment from these was cloned into the same sites of pLUX to create pGTUN3, pGTUN5, pGTUN7, and pGTUN9. Plasmid pLUX consisted of the 4.1-kb XbaI fragment from URA3 (22) in the XbaI site of LITMUS 28.

Site-specific mutation of the PHR1 promoter was achieved by inverse PCR. Plasmid pLTN3 was amplified with primers 5′-CTAGAAAAATATTCCATCTTTATAACC-3′ and 5′-ATTTTTTTTTTATATTGCAAGTGTCAG-3′. The primers incorporated a C-to-T transversion at position −825 and an A-to-T transition at position −823. The PCR product was phosphorylated and ligated to produce plasmid pLTN3X1. The AgeI-HindIII fragment from pLTN3X1 was used to replace the analogous region of pGTUN3, creating plasmid pGTUNX1 and effectively replacing the wild-type PHR1 promoter sequences with the mutated forms. Plasmid pGTUN3X2 was constructed in the same manner with primers 5′-TAGAAATTTTATTGAATATTTCAATCCTC-3′ and 5′-GATTTTATTTTCATTTGTTGTTCTTGTTG-3′ to introduce analogous mutations at positions −516 and −514. All four mutations were incorporated into plasmid pGTUN3X12, which was produced by ligation of the AgeI-PsiI fragment from pLTN3X1 and the PsiI-HindIII fragment from pLTN3X2 into the AgeI and HindIII sites of pGTUN3. All mutations were verified by DNA sequencing.

Construction of plasmids pA3BHG, pA2BHG, and pA1BHG paralleled the construction described by Nakayama et al. (31). The TATA box region of S. cerevisiae HOP1, nucleotides −168 to −3, was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of strain LL-20 with primers 5′-CCATGGCTAAATTGTACTTTATATATAGTTG-3′ and 5′-GACAAGCTTCCTGACTTTTCTGAG-3′, which introduced NcoI and HindIII sites, respectively, at the 5′ ends. The product was cloned into the NcoI and HindIII sites of LITMUS 28, creating plasmid pH3. The terminator region of S. cerevisiae ADH1, nucleotides +939 to +1305, was amplified with primers 5′-GACCGGTCAAGTCTCCAATCAAGG-3′ and 5′-CATGACGTCATTGCTGGAGTTAG-3′. The AgeI and AatII sites incorporated into the primers were used to clone the PCR product into the like sites of pH3, resulting in plasmid pAH. Synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotides of the form 5′-GACGTC(AAAAAAAAACCAAGAAAAA)xTATTCCATCTTTATAACCATGG-3′, where x equals 1, 2, or 3, were cloned into the AatII and NcoI sites of pAH between the upstream terminator and downstream TATA box sequences. The variable region of the oligonucleotides contained a Rim101p consensus binding sequence. The plasmids were called pA1BH, pA2BH, and pA3BH, indicating the presence of 1, 2, or 3 binding sites. A control plasmid, pA0BH, lacking Rim101p binding sites was produced in the same manner with the oligonucleotide 5′-GACGTC(AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA)2TATTCCATCTTTATAACCATGG-3′. The AgeI-HindIII fragments bearing these artificial promoters were used to replace the wild-type PHR1 promoter in plasmid pGTUN3, creating the plasmid series pAxBHGU, where x equals 0, 1, 2, or 3. The structures of the promoter inserts were verified by DNA sequencing. A control plasmid, pAHGU, lacking an oligonucleotide insert was constructed in an analogous manner with the AgeI-HindIII fragment from plasmid pAH.

The plasmids were transformed into C. albicans by using lithium acetate as previously described (18). Plasmid DNA was made linear prior to transformation by digestion at the unique NheI site adjacent to URA3 to target integration to the homologous locus. The locus of integration and the integrity of the integrated DNA were verified by Southern blot hybridization.

Plasmid pLUBP was constructed by ligation of the BglII-PstI fragment from URA3 (22) into the same sites of LITMUS 28. This URA3 fragment was used to restore the URA3 locus in strain CAR26.

Northern blot analyses.

Cultures for RNA preparation were established by inoculation of 50 ml of prewarmed medium 199, adjusted to either pH 4.0 or 7.5, to a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Cells cultured for 48 h on YPD at 28°C were used as the inoculum. The cultures were incubated for 4 h at 28°C on an orbital shaker. Cell harvesting, RNA extraction, and Northern blot preparation were performed as described previously (36).

Blots were hybridized with either a 730-bp HindIII-PstI fragment containing the GFP gene or the1.9-kb SalI fragment of C. albicans ACT1. Probes were labeled by random priming with [α-32P]dCTP and Ready-to-Go DNA labeling beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Hybridization intensities were quantified by phosphorimaging and normalized to that of ACT1.

Microarray analysis.

Cells were cultured and RNA was prepared essentially as described by Cowen et al. (6). An isolated colony of strain CAI12 or CAR2 was cultured for 48 h at 28°C on YPD. The cells were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 to 0.1 in 50 ml of prewarmed 199 medium (pH 7.5) and incubated at 28°C until an OD600 of 0.6 to 0.7 was achieved. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at room temperature, and the cell pellet was rapidly frozen by immersion in dry ice. Total RNA was extracted by using hot phenol (23). Polyadenylated RNA was isolated by using a Message Maker reagent assembly kit (Life Technologies, Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that incubation with resin was done for 30 min at 37°C and for an additional 90 min at room temperature. Purified mRNA was quantified by using a RiboGreen RNA quantification kit (Molecular Probes) and labeled by the aminoallyl protocol (SOP 004) developed at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR). Arrays (Candida Chips 5.2; Biotechnology Research Institute, Montreal, Canada; http://dirac.bri.nrc.ca/microarraylab/) were prehybridized and hybridized according to TIGR protocol SOP 005. Both protocols are available at http://www.tigr.org/tdb/microarray/protocolsTIGR.shtml.

Hybridized arrays were scanned with a GenePix 4000A (Axon Instruments, Inc.) at a 10-mm resolution. Image processing and quantification of intensities were performed by using SPOT Finder software (TIGR; http://www.tigr.org/softlab/) (19). Intensity values were normalized on the basis of the total intensity in each channel. Spots exhibiting a twofold or greater difference between the parent and the mutant in three independent experiments were independently quantified by end-point reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

End-point RT-PCR quantification of mRNA.

RNA was isolated from strains CAI12 and CAR2-U1 as described for microarray analysis and further purified by using RNeasy (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 5 μg of total RNA with primer dT18 and SuperScript II (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification of the cDNA was carried out with the gene-specific primers listed in Table 2. In addition to the gene-specific primers, each reaction contained ACT1 primers. Coamplification of ACT1 mRNA provided a quantification control and allowed the detection of contaminating DNA due to the 657-bp intron in ACT1 (11). The cDNA reaction mixture was diluted 1:4, and 1 μl was used in a 50-μl PCR mixture containing 12 pmol of each primer and 1.75 U of Taq polymerase. The MgCl2 concentration and annealing temperature were adjusted as necessary. Thermal cycles consisted of 5 min of denaturation at 94°C; 23 to 31 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at the appropriate annealing temperature, and 2 min at 72°C; and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. Amplification products were fractionated on 1.0% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and scanned with a Fluor-S Imager (Bio-Rad). Band intensities were quantified by using NIH Image.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for the end-point RT-PCR quantitation of mRNA

| Primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| act-F | 5′-AAAATATAATCATTCAAAATGGACGG-3′ |

| act-R | 5′-AATGAAGCCAAGATAGAACCACC-3′ |

| orf6.7614-F | 5′-TGACGGTGTCAACGATTCTCC-3′ |

| orf6.7614-R | 5′-GCATATCTTTGGAATGGGTCG-3′ |

| orf6.5731-F | 5′-TTTTTTGTTGTTGGTGGGTTCC-3′ |

| orf6.5731-R | 5′-CAGCAGACCTCAATTCATCAACC-3′ |

| orf6.4503-F | 5′-AGTTTGCGTATGATTTCTTTTTGG-3′ |

| orf6.4503-R | 5′-TTGATGGAGTTTGTGAATGATGG-3′ |

| orf6.8522-F | 5′-GATGCTGTAACTACGGCTAATGG-3′ |

| orf6.8522-R | 5′-ATAAGTTGGGAAATCGGTTGG-3′ |

| orf6.5814-F | 5′-CCAGTGGGTGCTATTGGTGAAG-3′ |

| orf6.5814-R | 5′-AAATCAACGTCAACTGAAGTGTGG-3′ |

| orf6.7524-F | 5′-TTCTTTGGTATCAATATGTATGAATGG-3′ |

| orf6.7524-R | 5′-ACGGACATACCACCAACAAATGC-3′ |

| orf6.6934-F | 5′-CGGTTACCAGATTTGTTGATGC-3′ |

| orf6.6934-R | 5′-GTGTGGCAATGCAGGTTAGC-3′ |

| orf6.8147-F | 5′-TGGCCAACAAGCGAGCAAAC-3′ |

| orf6.8147-R | 5′-TGTGCTTGGCAACATCCTTC-3′ |

| orf6.8439-F | 5′-GTATCACTTCAGCACCAGACTCC-3′ |

| orf6.8439-R | 5′-GCAATGGTAGAGTTTCCGTAGC-3′ |

| orf6.957-F | 5′-CTTGGGGTAGCTGGTTCTGC-3′ |

| orf6.957-R | 5′-AACAATATTGGTTTACTATCAGCAGG-3′ |

| orf6.6363-F | 5′-ACAAACATATTACCTACAAAACCACC-3′ |

| orf6.6363-R | 5′-CCCTGTAGTACATGAACCGCC-3′ |

| orf6.3969-F | 5′-TTCAATCAATTACAAAACATTACTGG-3′ |

| orf6.3969-R | 5′-TCAATACCATACCAGGAACAACC-3′ |

| orf6.5009-F | 5′-ATACGGTGACGGAATGAGAGG-3′ |

| orf6.5009-R | 5′-TGAAAACACTAGAGCAACGATACC-3′ |

| orf6.8476-F | 5′-TGGCGACGGCACTAACC-3′ |

| orf6.8476-R | 5′-TTCAGAAACGATACTGCTCACC-3′ |

| orf6.5928-F | 5′-GCCATTATCAGTGTTTTATTTTCG-3′ |

| orf6.5928-R | 5′-TTCAATGCATCCACTTTTTCC-3′ |

| orf6.3107-F | 5′-CAAAACGGAAAATAGTCACTGCTGC-3′ |

| orf6.3107-R | 5′-GTGCCTACCCAAATGTCACC-3′ |

| orf6.1543-F | 5′-CATGAAGCCAATATTCTTACTCG-3′ |

| orf6.1543-R | 5′-CACCACTACTATTTTTGCTGTTGC-3′ |

| orf6.4212-F | 5′-TTGCGTCATGGTGCTGC-3′ |

| orf6.4212-R | 5′-GAAAGTAAGCTCAGATGGGTAGG-3′ |

| orf6.897-F | 5′-CTTGCGTCATGGTGCTGC-3′ |

| orf6.897-R | 5′-AGAAAGTAAGCTCAGATGGGTAGG-3′ |

| orf6.1540-F | 5′-CAGAAGACGATGAAGAAGAAGAGG-3′ |

| orf6.1540-R | 5′-GATAATGCAGCAGCTAATGTAAACC-3′ |

| orf6.6260-F | 5′-GGTATAAACATGTACGAATGGTGTGG-3′ |

| orf6.6260-R | 5′-GTAATTAAACCGAAACCAACAACG-3′ |

| orf6.450-F | 5′-TGAAATTCTCCACCACTTTATTAGC-3′ |

| orf6.450-R | 5′-ACCAGCACCAGCGACAGG-3′ |

| orf6.5470-F | 5′-GCACTTAACATTTCCCCTTTCC-3′ |

| orf6.5470-R | 5′-TCAAAACCAATGCTGCTAAGG-3′ |

RESULTS

Rim101p recognizes sequences upstream of PHR1.

The putative transcription factor Rim101p/Prr2p is required for the pH-conditional expression of several genes of C. albicans (8, 36). Prior studies demonstrated that Rim101p acts in a positive manner to effect alkaline pH-induced expression of PHR1 (8, 36). The orthologous PacC of A. nidulans enhances gene expression at alkaline pH through its binding via a zinc finger domain to a well-characterized consensus sequence, 5′-GCCARG-3′ (17). Strong conservation within the zing finger domains of PacC and Rim101p, the only well-conserved regions of these proteins, suggested that DNA recognition was similarly preserved.

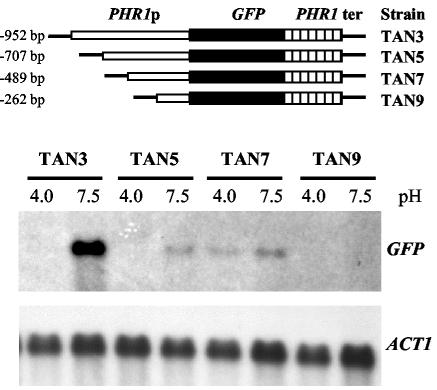

A 1,172-bp region upstream of the PHR1-2 (38) coding region was sequenced. Examination of the sequence failed to reveal any instances of the PacC consensus binding sequence. Nonetheless, the functional significance of this region was demonstrated by cloning nucleotides −952 to −8 of PHR1 upstream of the GFP gene. The resulting reporter construct was integrated at the URA3 locus of strain CAI4 by homologous recombination to generate strain TAN3. The fidelity of integration was verified by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Although GFP expression was inadequate to impart detectable fluorescence, GFP mRNA was readily measured. As shown in Fig. 1, GFP gene expression paralleled the pH-conditional expression of native PHR1 with comparable mRNA abundances (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Deletion analysis identified two regions within this 944-bp fragment that were important for pH-conditional expression. Analogous GFP gene fusions were constructed to contain the sequences between −707 and −8, −489 and −8, and −262 and −8. The resulting plasmids were integrated as described above to generate strains TAN5, TAN7, and TAN9, respectively (Fig. 1). As in TAN3, GFP gene expression in TAN5 was pH conditional and paralleled PHR1 expression. However, the mRNA abundance was 90% lower. The removal of an additional 218 nucleotides of sequence upstream of PHR1, as in TAN7, eliminated pH-conditional expression and resulted in low-level constitutive expression of the GFP gene. No expression was detected when the smallest fragment, nucleotides −262 to −8, was placed upstream of the GFP gene, as in TAN9. These results indicated that pH-conditional expression was influenced by at least two sequences, one located between positions −952 and −707 and the other located between positions −707 and −489.

FIG. 1.

Effects of upstream deletions on PHR1 promoter-GFP gene expression. A GFP gene was fused with progressive 5′ deletions of the promoter region of PHR1 (PHR1p). (Upper panel) Structures of the resulting reporter genes. For each construct, the 5′ end point of the PHR1 promoter sequence is indicated to the left, and the strain containing an integrated copy is indicated to the right. ter, terminator. (Lower panel) Results of Northern blot hybridization. The indicated strains were cultured at either pH 4.0 or pH 7.5, and a Northern blot of total RNA extracted from the cells was probed with GFP and ACT1 DNAs.

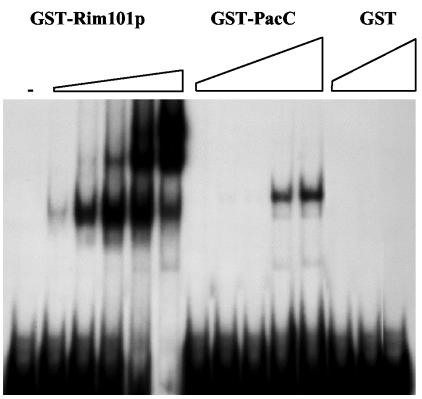

The absence of the PacC consensus binding sequence suggested either that Rim101p does not bind upstream of PHR1 or that the nucleotide sequence recognized by Rim101p differs from that recognized by PacC. To distinguish between these possibilities, the capacity of recombinant Rim101p to bind upstream of PHR1 was tested in EMSAs. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that the mobilities of DNA fragments spanning nucleotides at positions −952 to −707 or positions −707 to −489 were similarly retarded when they were preincubated with GST-Rim101p and that this interaction was not inhibited by excess nonspecific DNA (data not shown). Binding to nucleotides at positions −952 to −707 was further localized to a region between positions −864 and −707. This DNA fragment was designated N4/H3 in subsequent experiments. As shown in Fig. 2, the mobility of N4/H3 decreased in the presence of GST-Rim101p but was not affected by GST alone. Furthermore, the amount of N4/H3 retarded was directly proportional to the amount of GST-Rim101p present. Together, these results demonstrated that Rim101p could bind sequences upstream of PHR1. The electrophoretic pattern contained two retarded complexes, suggesting either the presence of two Rim101p binding sites within N4/H3 or oligomerization of GST-Rim101p, possibly through the GST moiety (4, 32). The latter interpretation is supported by subsequent experiments demonstrating that dual retardation complexes are formed in the presence of oligonucleotides containing a single binding site.

FIG. 2.

EMSA of a PHR1 promoter fragment in the presence of GST-Rim101p or GST-PacC. The 157-bp region of the PHR1 promoter designated N4/H3 was labeled with 32P and incubated with 0, 0.09, 0.18, 0.9, 1.8, and 3.6 μg of GST-Rim101p; 0.17, 0.85, 1.7, 3.4, and 10 μg of GST-PacC; or 1.8, 3.6, and 9 μg of GST. Following electrophoresis, labeled DNA was visualized by autoradiography.

The ability of Rim101p to bind sequences upstream of PHR1 implied that the binding specificity of Rim101p differs from that of PacC and led to the supposition that PacC would be unable to bind these DNA fragments. As an intended negative control, this prediction was tested by using a GST-PacC fusion protein. Unexpectedly, PacC did retard the mobility of PHR1 DNA; however, a substantially higher concentration of GST-PacC was required (Fig. 2).

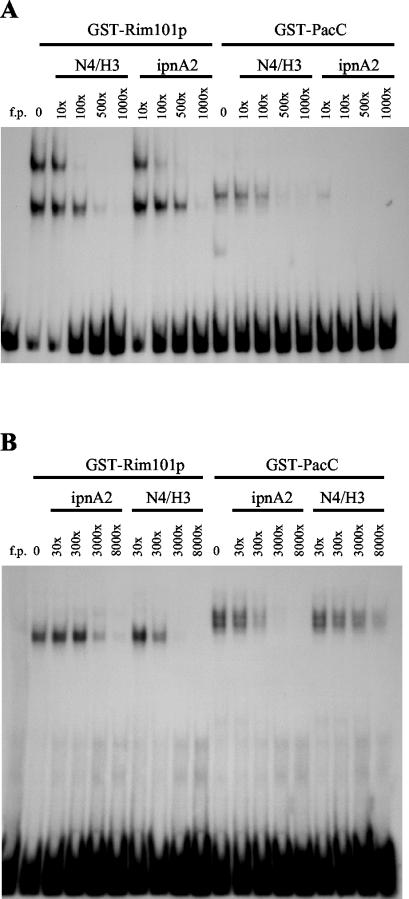

The implied distinction in the binding specificities of Rim101p and PacC was supported by binding competition experiments. The interaction of N4/H3 DNA with GST-Rim101p was efficiently blocked by unlabeled N4/H3 DNA but not ipnA2 DNA (Fig. 3A). The latter is a synthetic oligonucleotide containing an authentic PacC binding site (15). Similar binding inhibition required an approximately fivefold-higher molar concentration of ipnA2 DNA than of N4/H3 DNA (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the interaction of GST-PacC with N4/H3 was more effectively competed by ipnA2 DNA than by N4/H3 DNA (Fig. 3A). This inverse pattern of competition was also observed when ipnA2 DNA instead of N4/H3 DNA was used as the binding probe. N4/H3 was more effective at blocking the interaction with GST-Rim101p, and ipnA2 was 10- to 100-fold more effective at inhibiting GST-PacC binding (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Rim101p and PacC have different binding specificities. GST-Rim101p or GST-PacC was incubated with 32P-labeled N4/H3 (A) or ipnA2 (B) DNA and various amounts of the indicated unlabeled DNA. GST-Rim101p binding reaction mixtures contained 0.15 μg of protein (A) and 0.36 μg of protein (B). The amounts of GST-PacC used were 10 μg (A) and 1 μg (B). 1× N4/H3 or ipnA2 DNA equaled 1.33 × 10−14 mol (A) or 7.6 × 10−16 mol (B). Following electrophoresis, labeled DNA was visualized by autoradiography. f.p., free probe.

CAST determination of Rim101p binding specificity.

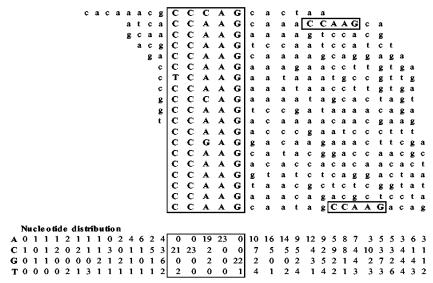

Since the binding studies suggested that the specificity of Rim101p differed from that of PacC, CAST analysis (44) was performed as described by Aoki et al. (1) to define a consensus recognition sequence for Rim101p. The oligonucleotides used for selection contained 20 random nucleotides flanked by fixed primer binding sequences. This random pool of oligonucleotides was mixed with GST-Rim101p, and oligonucleotides bound by the protein were recovered by affinity chromatography with glutathione-Sepharose. Eluted oligonucleotides were amplified by PCR, and the amplification products were used in a subsequent round of selection. Six cycles of selection were performed to eliminate nonspecific or weakly binding sequences, and the final amplification products were cloned into pTOPO-RT. Twenty-three clones were sequenced, and 21 unique inserts were identified. Alignment of the insert sequences (Fig. 4) demonstrated the presence of a consensus pentanucleotide, 5′-CCAAG-3′, followed preferentially by A or C in the adjacent 3′ positions. This sequence was related to but distinct from the PacC consensus binding site sequence, 5′-GCCARG-3′ (17).

FIG. 4.

Rim101p consensus binding site. The nucleotide sequences of CAST-selected oligonucleotides were aligned around a conserved pentanucleotide motif (boxed regions). The nucleotide distribution matrix is shown below the nucleotide sequences.

Rim101p consensus binding sites upstream of PHR1 are required for expression.

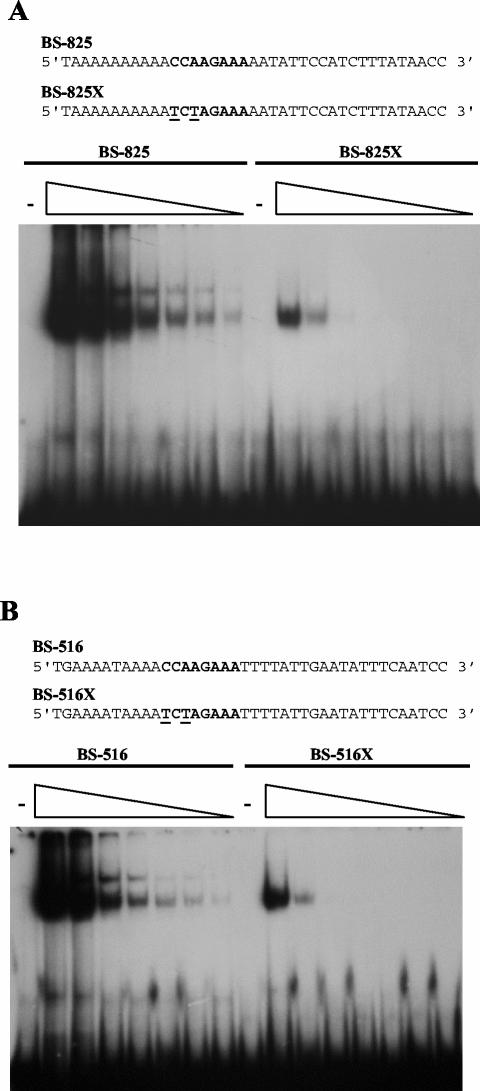

Three potential Rim101p binding sites lay within the region containing positions −952 to −8 upstream of PHR1. These were identified by using MatInspector (40), and a matrix description was derived from the nucleotide distribution of the aligned CAST sequences. The weakest match, CCTAGAAA, had a matrix similarity of 0.86 and was located at position −935. The other two matches had high matrix similarities, 0.98 and 0.96, and were located at nucleotides −825 and −516, respectively. These three sites were located within regions at positions −952 to −707 and positions −707 to −489, defined as functionally significant by deletion analysis. The ability of Rim101p to recognize these consensus binding sites was tested by EMSAs with synthetic double-stranded oligomers. No interaction was detected with the oligonucleotide containing the site at position −934, even with high concentrations of GST-Rim101p (data not shown). However, binding was readily detected with oligonucleotides containing the site at either position −825 or position −516 (Fig. 5). The specificity of this interaction was demonstrated by using oligonucleotides in which the core consensus sequence CCAAG was changed to TCTAG. This alteration dramatically reduced GST-Rim101p binding (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Rim101p binds consensus sequences within the PHR1 promoter. (A) GST-Rim101p (0, 1.8, 0.360, 0.180, 0.090, 0.045, 0.022, and 0.011 μg) was incubated with an oligonucleotide containing either the wild-type consensus sequence located at position −825 of the PHR1 promoter (BS-825) or a mutated version of the site (BS-825X). (B) As for panel A, except that the oligonucleotide contained the consensus sequence located at position −516 (BS-516) or a mutated site (BS-516X). The sequences of the oligonucleotides are shown above the panels. The consensus binding site is indicated in bold type, and mutated nucleotides are underlined.

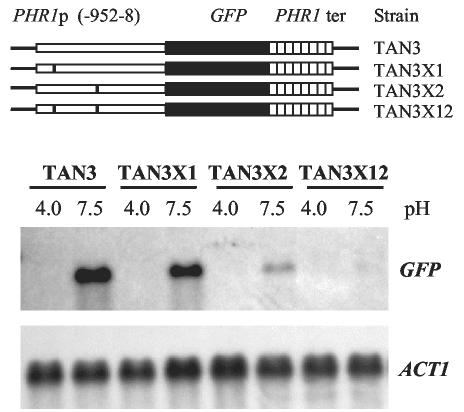

The functional significance of these consensus binding sites within the context of the PHR1 promoter was demonstrated by site-specific mutagenesis. The CCAAG-to-TCTAG mutations were incorporated into the site at either position −825 or position −516 or both sites in the GFP reporter plasmid pGTUN3. Following integration into the genome, the effect of the mutations on GFP gene expression was measured. Mutation of the distal site did not eliminate pH-conditional expression. However, expression at pH 7.5 was reduced by 52% relative to that obtained with the wild-type promoter (Fig. 6, strains TAN3 and TAN3X1). Expression was even more severely reduced, 82%, by mutation of the proximal site, but again, pH-conditional expression was maintained (Fig. 6, strain TAN3X2). Incorporation of both mutations resulted in the loss of all detectable expression (Fig. 6, strain TAN3X12). Comparable results were obtained in three independent expression experiments. Thus, the consensus binding sites at both positions −825 and −516 are functional upstream activating sequences essential for pH-conditional expression from the PHR1 promoter.

FIG. 6.

Functional test of Rim101p consensus binding sites in the PHR1 promoter. A GFP gene was fused with either the wild-type PHR1 promoter (PHR1p) or promoters in which one or both Rim101p consensus binding sites were mutated. (Upper panel) Structures of reporter genes. A vertical bar within the PHR1 promoter region indicates the presence and approximate position of a mutated binding site. To the right of each construct is indicated the strain containing an integrated copy of the reporter. ter, terminator. (Lower panel) Results of Northern blot hybridization. The indicated strains were cultured at either pH 4.0 or pH 7.5, and a Northern blot of total RNA extracted from the cells was probed with GFP and ACT1 DNAs.

Rim101p binding sites are sufficient to confer pH-conditional expression.

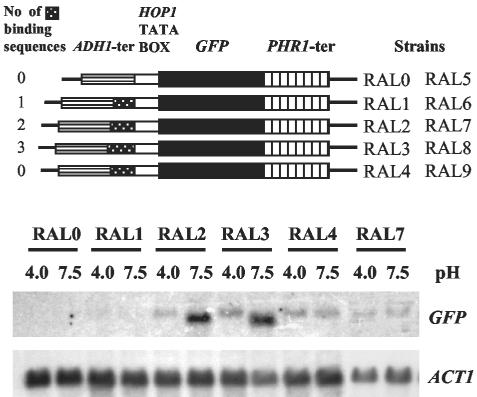

To ascertain whether Rim101p binding sites were sufficient for pH-conditional regulation, a synthetic promoter containing zero to three copies of the Rim101p consensus binding sequence was assembled. The promoter was constructed essentially as described by Nakayama et al. (31) and consisted of the yeast ADH1 terminator region cloned upstream of the yeast HOP1 TATA box, which was adjacent to the GFP gene as the downstream reporter. Oligonucleotides containing Rim101p binding sites were cloned between the ADH1 and the HOP1 sequences (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Rim101p consensus binding sequence confers pH-conditional expression. Synthetic promoters were constructed to contain 1, 2, or 3 copies of the Rim101p consensus binding sequence placed between the ADH1 terminator and the HOP1 TATA box region, upstream of the GFP gene. (Upper panel) Structures of the resulting reporter genes. The number of Rim101p binding sites is indicated to the left. The reporter genes were integrated into either CAI4 or CAR26 (rim101/rim101), resulting in strains RAL0 to RAL4 and RAL5 to RAL9, respectively. ter, terminator. (Lower panel) Results of Northern blot hybridization. The indicated strains were cultured at either pH 4.0 or pH 7.5, and a Northern blot of total RNA extracted from the cells was probed with GFP and ACT1 DNAs.

In the absence of a Rim101p binding site, no detectable GFP gene expression occurred, as shown for the control strains RAL0 and RAL5 (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Similarly, no expression was seen, regardless of pH, when a single binding site was incorporated, as in strains RAL1 and RAL6 (Fig. 7 and data not shown). However, insertion of either two or three binding sites conferred pH-conditional transcription. In these strains, RAL2 and RAL3, respectively, two transcripts, which differed 4- to 10-fold in abundance, were observed. The shorter, more abundant transcript paralleled native PHR1 expression and was highly expressed at pH 7.5 but not detectable at pH 4.0 (Fig. 7). Its expression was also RIM101 dependent, as demonstrated by its absence when the artificial promoters were tested in a Δrim101 background (Fig. 7, strains RAL7 and RAL8, and data not shown). Furthermore, the expression of this transcript required the Rim101p consensus binding sites. Substituting the sequence AAAAA for both CCAAG sequences in the promoter eliminated the expression of the shorter transcript in both wild-type and Δrim101 backgrounds (strains RAL4 and RAL9, respectively) (Fig. 7 and data not shown). These results demonstrated that the consensus binding sites were sufficient to confer pH-conditional RIM101-dependent transcription.

In contrast, the longer, less abundant transcript was expressed only at acid pH in the wild-type background, as seen in strain RAL2, but was constitutively expressed in strain RAL7, which has a Δrim101 background (Fig. 7). Substitution of the sequence CCAAG with AAAAA did not prevent the expression of the longer transcript but did result in its constitutive expression in a wild-type background (Fig. 7, strain RAL4). The nature and implications of this transcript are considered in the Discussion.

Rim101p binding sites are common to RIM101-dependent genes.

There was a strong association between RIM101-dependent gene expression and the presence of upstream Rim101p binding sites. Six genes, detected by microarray analysis and verified by RT-PCR, whose expression was enhanced at least twofold in Rim101p-expressing versus non-Rim101p-expressing cells at pH 7.5, were identified (Table 3). These, in addition to two previously reported genes, RIM101 and PRA1 (8, 36), were examined for the presence of Rim101p binding sites within 1 kb upstream of the coding region. Binding sites were identified by using MatInspector (40) and defined as sequences with a matrix match score of ≥0.962 by using the nucleotide matrix defined by CAST analysis. This cutoff value is equivalent to the lower score for the two functional binding sites upstream of PHR1. By this criterion, the region upstream of six of the eight positively regulated genes contained at least one binding site (Table 3). The probability that this scenario would occur by chance is 7.8 × 10−5, based on an analysis of 1,000 randomly selected 1-kb segments of the C. albicans genome. The frequency of random segments containing at least one binding site was 0.124 ± 0.010 (n = 5). Of the eight putative binding sites, only one was preceded by a G residue and thus conformed to the PacC consensus binding site (43).

TABLE 3.

Rim101p binding sites upstream of positively regulated genesa

| Open reading frame | Gene nameb | Function | No. of Rim101p binding sitesc |

|---|---|---|---|

| orf6.7614 | (ENA2) | Plasma membrane-type ATPase involved in Na+ efflux | 1 |

| orf6.5731 | (FRE4) | Ferric reductase | 1 |

| orf6.4503 | (FRE5) | Ferric reductase transmembrane component | 0 |

| orf6.8522 | SKN1 | β-1,6-Glucan synthesis | 2 |

| orf6.5814 | PHO8 | Repressible alkaline phosphatase | 1 |

| orf6.7524 | PHR1 | β-1,3-Glucanosyltransferase | 2 |

| orf6.6934 | PRA1 | pH-regulated antigen | 0 |

| orf6.8147 | RIM101 | Transcription factor; regulation of pH response | 2 |

| orf6.8439 | WAP1/CSA1-1 | TUP1-regulated cell wall protein | 1 |

Genes listed are those detected by microarray analysis and verified by RT-PCR.

Gene names are either previously published names or those annotated in the C. albicans genome project. Names in parentheses are those of the most closely related C. albicans or S. cerevisiae genes.

Binding sites were defined as sequences with a score of ≥0.962 compared with the nucleotide matrix defined by CAST analysis.

Since RIM101 negatively regulates the expression of PHR2 (8, 36), genes that were derepressed in the absence of the regulator were also examined (Table 4). In this experiment, the association was less strong but was still much greater than random. Six of the 14 genes identified contained an upstream Rim101p binding site, a random expectation of 3.8 × 10−3, and only 1 of the 7 potential binding sites conformed to the PacC consensus binding site. These results support the contention that the correct Rim101p binding site sequence has been identified and suggest that transcription of many of these genes is directly influenced by Rim101p.

TABLE 4.

Rim101p binding sites upstream of negatively regulated genesa

| Open reading frame | Gene nameb | Function | No. of Rim101p binding sitesc |

|---|---|---|---|

| orf6.957 | CCP1 | Cytochrome c peroxidase | 0 |

| orf6.6363 | CHA1 | l-Serine/l-threonine deaminase | 0 |

| orf6.3969 | ECM33 | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored cell surface protein | 0 |

| orf6.5009 | FET99 (FET3) | Iron transport multicopper oxidase | 1 |

| orf6.8476 | FRE7 | Ferric reductase transmembrane component | 0 |

| orf6.5928 | GIT99 (GIT1) | Glycerophosphoinositol transporter | 1 |

| orf6.3107 | (MNN1) | α-1,3-Mannosyltransferase | 0 |

| orf6.1543 | (MNN4) | Phosphorylation of manno-oligosaccharides | 1 |

| orf6.4212 | PHO11 | Secreted acid phosphatase | 0 |

| orf6.897 | PHO11 | Secreted acid phosphatase | 0 |

| orf6.1540 | PHO99 (PHO87) | Phosphate transporter | 1 |

| orf6.6260 | PHR2 | β-1,3-Glucanosyltransferase | 2 |

| orf6.450 | Unknown | 0 | |

| orf6.5470 | Unknown | 1 |

Genes listed are those detected by microarray analysis and verified by RT-PCR.

Gene names are either previously published names or those annotated in the C. albicans genome project. Names in parentheses are those of the most closely related C. albicans or S. cerevisiae genes.

Binding sites were defined as sequences with a score of ≥0.962 compared with the nucleotide matrix defined by CAST analysis.

DISCUSSION

Like PaC, Rim101p of C. albicans was shown to exhibit sequence-specific binding of DNA. While this result was anticipated, the binding specificities were unexpectedly diverged. This result was unexpected, since the DNA binding zinc finger domains of these proteins are highly conserved (8, 36). The difference in sequence recognition was evidenced in two independent experimental approaches. First, competition binding studies showed that Rim101p binding to PHR1 promoter sequences was more effectively competed by native PHR1 DNA than by DNA containing a PacC consensus binding site. Conversely, PacC binding was more effectively competed by DNA containing a PacC consensus binding site than by PHR1 DNA. Second, the sequences of in vitro-selected oligonucleotides did not conform to the PacC consensus sequence.

Although the core Rim101p binding site sequence, 5′-NCCAAG-3′, bore similarity to the PacC consensus sequence, 5′-GCCARG-3′, there are two distinct differences. The initial G residue of the PacC sequence is critical for binding; recognition is drastically reduced by substitution with any other nucleotide (17). In contrast, there was no evidence of nucleotide preference at this position in the CAST-selected sequences. Furthermore, neither of the two functional binding sites in the PHR1 promoter contained guanine at this position; both contained adenine. Whereas A or G is acceptable in the fifth position of the PacC binding site sequence (17), only A was present in the PHR1 promoter binding sites and the in vitro-selected binding sites.

The basis of these binding differences is unclear. An elegant molecular analysis of the contacts between DNA and the zinc fingers of PacC provided a detailed model of these interactions (17). All of the amino acids identified as having key DNA contacts are conserved in Rim101p, including K125 of PacC, which is believed to interact with the first guanine (17). This finding suggests that one or more of the different amino acids critically affect interactions with DNA.

The functional significance of the in vitro-defined Rim101p binding site sequence was validated by the demonstrations that putative Rim101p recognition sequences in the PHR1 promoter were required for pH-conditional expression and that the Rim101p binding site sequence conferred pH-conditional expression to an ersatz promoter. Simultaneous inactivation of both the −825 and the −516 binding sites of PHR1 by site-specific mutagenesis resulted in the complete loss of PHR1 expression. Inactivation of either site alone led to a reduction in expression, but pH-conditional regulation was maintained. These results indicated that a single Rim101p binding site is sufficient to confer pH-conditional expression, a conclusion supported by promoter deletion studies. Strain TAN5 contained a GFP reporter gene fused with nucleotides −707 to −8 of the PHR1 promoter and thus contained only the −516 binding site. Nonetheless, GFP gene expression was pH conditional. The only contrary data were obtained with the artificial promoter, in which a single Rim101p binding site did not confer detectable transcriptional activity. However, the significance of this result is difficult to assess given the nonnative context.

Although a single binding site was sufficient, multiple binding sites enhanced expression. Mutation of either the −825 or the −516 binding site resulted in a substantial decline in the level of expression, indicating that both sites contribute to the rate of transcription. Similarly, a comparison of GFP gene expression in strains TAN3 and TAN5 demonstrated that deletion of the distal site decreased transcription. Expression from the artificial promoter was also influenced by the number of Rim101p binding sites. The presence of three Rim101p binding sites yielded alkaline pH-induced expression approximately twofold above that obtained with two binding sites. However, in this context, the enhancement could reflect the repositioning of binding sites, since an additional length of sequence was added along with the third binding site. Of the two binding sites in the native promoter, the proximal site appears to be more important, since inactivation of this site reduced expression approximately fivefold, versus the twofold effect of the distal site.

Similar conclusions were reached in studies of the ipnA promoter of A. nidulans. The expression of ipnA is pH conditional by virtue of three upstream PacC binding sites (15). Any one of the three sites is sufficient for pH-conditional expression, but each contributes differentially to the overall level of expression (15). Interestingly, the site of highest affinity contributed the least enhancement (15). Similarly, two PacC binding sites are present upstream of alkaline pH-inducible pcbC, which encodes the ipnA ortholog of A. chrysogenum (39). Both bind PacC in vitro, but only the distal site appears to contribute to pH-conditional expression in vivo (39).

The behavior of the artificial promoter was of interest in several regards. Two alternately expressed mRNAs emanated from this promoter. The smaller, more abundant transcript mimicked PHR1. Its expression was detected at alkaline but not acid pH and was dependent upon the presence of Rim101p binding sites and Rim101p. These results conclusively demonstrated that Rim101p binding sites are necessary and sufficient for alkaline pH-inducible gene expression.

The alternate transcript was expressed only at acid pH in Rim101p-expressing cells but was constitutively expressed in the absence of RIM101 or Rim101p binding sites. This expression pattern parallels that of the acid pH-expressed gene PHR2, which becomes constitutive in the absence of Rim101p (8, 36). The increased length of this alternate mRNA indicates that it initiates upstream of the Rim101p-induced transcripts, and its repression at alkaline pH suggests that Rim101p binding downstream of the initiation site blocks expression. Thus, Rim101p appears to act as a negative regulator to confer an acid pH-enhanced pattern of expression, analogous to PacC. In A. nidulans, the permease for γ-aminobutyrate is an acid pH-expressed gene under the control of PacC (20). Overlapping binding sites in the promoter allow PacC to competitively block the binding of the activator IntA at alkaline pH (13). The features of the artificial promoter that imparted transcription from the upstream binding site were not investigated. However, it is worth noting that the oligonucleotides used in its construction contained extensive poly(dA-dT) tracts, which activate transcription from many promoters (21).

The presence of Rim101p binding sites upstream of a number of RIM101-dependent genes suggests that Rim101p directly regulates their expression and, conversely, indicates that the appropriate consensus binding site has been identified. These data also demonstrate that the targets of Rim101p control have both similarities with and differences from PacC-regulated genes. As in A. nidulans, both acid and alkaline phosphatases of C. albicans have remained under the control of the pH response pathway. More generally, all of the genes positively regulated by RIM101 and many of the negatively regulated ones encode known or putative cell surface proteins. These data are in accord with the hypothesis proposed for A. nidulans that a primary role of the pH response pathway is to ensure that the proteins exposed to the external milieu are those adapted for efficient functioning under extant ambient conditions (3). However, few additional targets of PacC are known, limiting comparison. The isopenicillin synthase gene is not present in C. albicans, and the γ-aminobutyrate permease gene was not detected in our screen. GEL1, an A. nidulans ortholog of PHR1 and PHR2, does not exhibit a pH-conditional response (29), suggesting that it is not regulated by PacC.

The ability of C. albicans Rim101p to function as a transcriptional activator stands in contrast to the function of Rim101p in S. cerevisiae. In S. cerevisiae, Rim101p acts primarily as a repressor (24). Whereas most of the positively regulated genes in C. albicans contained putative Rim101p binding sites upstream, consistent with their activation via Rim101p, in S. cerevisiae only negatively regulated genes exhibited potential binding sites (24). Two of these negatively regulated genes are themselves negative regulators, NRG1 and SMP1, and they mediate, in part, the biological role of RIM101 (24). Comparable sequential repression pathways do not appear to be as important for Rim101p in C. albicans. Based on our microarray analysis, NRG1 expression was not influenced by RIM101. NRG1 represses over 200 genes in C. albicans (30). Over 90% of those were represented on the microarrays used in this study, yet only one NRG1-regulated gene, FRE4, was among the RIM101-regulated genes reported here. Moreover, ENA1/ENA2 and ZPS/PRA1, homologous targets of RIM101 control in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, respectively, are negatively regulated by NRG1 in Saccharomyces but not in Candida (30).

In conclusion, Rim101p, like the orthologous PacC, is a transcriptional activator directly imparting alkaline pH-induced expression. Preliminarily, it appears also to be capable of acting as a negative regulator to impart acid pH-enhanced expression.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI50800 from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Ivana V. Yang for useful advice on the microarray analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki, K., G. Meng, K. Suzuki, T. Takashi, Y. Kameoka, K. Nakahara, R. Ishida, and M. Kasai. 1998. RP58 associates with condensed chromatin and mediates a sequence-specific transcriptional repression. J. Biol. Chem. 273:26698-26704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkani, A. E., O. Kurzai, W. A. Fonzi, A. M. Ramon, A. Porta, M. Frosch, and F. A. Mühlschlegel. 2000. Dominant active alleles of RIM101 (PRR2) bypass the pH restriction on filamentation of Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4635-4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caddick, M. X., A. G. Brownlee, and H. N. J. Arst. 1986. Regulation of gene expression by pH of the growth medium in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 203:346-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catt, D., W. Luo, and D. G. Skalnik. 1999. DNA-binding properties of CCAAT displacement protein cut repeats. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-Le-Grand) 45:1149-1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cormack, B. P., G. Bertram, M. Egerton, N. A. R. Gow, S. Falkow, and A. J. Brown. 1997. Yeast-enhanced green fluorescent protein (yEGFP): a reporter of gene expression in Candida albicans. Microbiology 143:303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowen, L. E., A. Nantel, M. S. Whiteway, D. Y. Thomas, D. C. Tessier, L. M. Kohn, and J. B. Anderson. 2002. Population genomics of drug resistance in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:9284-9289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, D., J. E. Edwards, Jr., A. P. Mitchell, and A. S. Ibrahim. 2000. Candida albicans RIM101 pH response pathway is required for host-pathogen interactions. Infect. Immun. 68:5953-5959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis, D., R. B. Wilson, and A. P. Mitchell. 2000. RIM101-dependent and -independent pathways govern pH responses in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:971-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denison, S. H. 2000. pH regulation of gene expression in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 29:61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diez, E., J. Alvaro, E. A. Espeso, L. Rainbow, T. Suarez, J. Tilburn, J. H. N. Arst, and M. A. Peñalva. 2002. Activation of the Aspergillus PacC zinc finger transcription factor requires two proteolytic steps. EMBO J. 21:1350-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnelly, S. M., D. J. Sullivan, D. B. Shanley, and D. C. Coleman. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis and rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis based on analysis of ACT1 intron and exon sequences. Microbiology 145:1871-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrlich, K. C., B. G. Montalbano, a. J. W. Cary, and P. J. Cotty. 2002. Promoter elements in the aflatoxin pathway polyketide synthase gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1576:171-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espeso, E. A., and H. N. Arst, Jr. 2000. On the mechanism by which alkaline pH prevents expression of an acid-expressed gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3355-3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espeso, E. A., and M. A. Peñalva. 1992. Carbon catabolite repression can account for the temporal pattern of expression of a penicillin biosynthetic gene in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1457-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espeso, E. A., and M. A. Peñalva. 1996. Three binding sites for the Aspergillus nidulans PacC zinc-finger transcription factor are necessary and sufficient for regulation by ambient pH of the isopenicillin N synthase gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271:28825-28830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espeso, E. A., T. Roncal, E. Diez, L. Rainbow, E. Bignell, J. Alvaro, T. Suarez, S. H. Denison, J. Tilburn, H. N. Arst, Jr., and M. A. Peñalva. 2000. On how a transcription factor can avoid its proteolytic activation in the absence of signal transduction. EMBO J. 19:719-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espeso, E. A., J. Tilburn, L. Sanchez-Pulido, C. V. Brown, A. Valencia, H. N. Arst, Jr., and M. A. Peñalva. 1997. Specific DNA recognition by the Aspergillus nidulans three zinc finger transcription factor PacC. J. Mol. Biol. 274:466-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gietz, D., A. St. Jean, R. A. Woods, and R. H. Schiestl. 1992. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1425.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegde, P., R. Qi, K. Abernathy, C. Gay, S. Dharap, R. Gaspard, J. E. Hughes, E. Snesrud, N. Lee, and J. Quackenbush. 2000. A concise guide to cDNA microarray analysis. BioTechniques 29:548-550, 552-554, 556 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchings, H., K. P. Stahmann, S. Roels, E. A. Espeso, W. E. Timberlake, H. N. Arst, Jr., and J. Tilburn. 1999. The multiply-regulated gabA gene encoding the GABA permease of Aspergillus nidulans: a score of exons. Mol. Microbiol. 32:557-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iyer, V., and K. Struhl. 1995. Poly(dA:dT), a ubiquitous promoter element that stimulates transcription via its intrinsic DNA structure. EMBO J. 14:2570-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly, R., S. M. Miller, M. B. Kurtz, and D. R. Kirsch. 1987. Directed mutagenesis in Candida albicans: one-step gene disruption to isolate ura3 mutants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:199-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohrer, K., and H. Domdey. 1991. Preparation of high molecular weight RNA. Methods Enzymol. 194:398-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb, T. M., and A. P. Mitchell. 2003. The transcription factor Rim101p governs ion tolerance and cell differentiation by direct repression of the regulatory genes NRG1 and SMP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:677-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert, M., S. Blanchin-Roland, F. Le Louedec, A. Lepingle, and C. Gaillardin. 1997. Genetic analysis of regulatory mutants affecting synthesis of extracellular proteinases in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica: identification of a RIM101/pacC homolog. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3966-3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacCabe, A. P., J. P. Van den Hombergh, J. Tilburn, H. N. Arst, Jr., and J. Visser. 1996. Identification, cloning and analysis of the Aspergillus niger gene pacC, a wide domain regulatory gene responsive to ambient pH. Mol. Gen. Genet. 250:367-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madzak, C., S. Blanchin-Roland, R. R. Cordero Otero, and C. Gaillardin. 1999. Functional analysis of upstream regulating regions from the Yarrowia lipolytica XPR2 promoter. Microbiology 145:75-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mingot, J. M., E. A. Espeso, E. Diez, and M. A. Peñalva. 2001. Ambient pH signaling regulates nuclear localization of the Aspergillus nidulans PacC transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1688-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mouyna, I., T. Fontaine, M. Vai, M. Monod, W. A. Fonzi, M. Diaquin, L. Popolo, R. P. Hartland, and J. P. Latge. 2000. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored glucanosyltransferases play an active role in the biosynthesis of the fungal cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14882-14889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murad, A. M., C. d'Enfert, C. Gaillardin, H. Tournu, F. Tekaia, D. Talibi, D. Marechal, V. Marchais, J. Cottin, and A. J. Brown. 2001. Transcript profiling in Candida albicans reveals new cellular functions for the transcriptional repressors CaTup1, CaMig1 and CaNrg1. Mol. Microbiol. 42:981-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama, H., T. Mio, S. Nagahashi, M. Kokado, M. Arisawa, and Y. Aoki. 2000. Tetracycline-regulatable system to tightly control gene expression in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 68:6712-6719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nemoto, T., Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Shimazaki, S., and O. M. 1994. Dimerization characteristics of the DNA- and steroid-binding domains of the androgen receptor. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 50:225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orejas, M., E. A. Espeso, J. Tilburn, S. Sarkar, H. N. Arst, Jr., and M. A. Peñalva. 1995. Activation of the Aspergillus PacC transcription factor in response to alkaline ambient pH requires proteolysis of the carboxy-terminal moiety. Genes Dev. 9:1622-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orr-Weaver, T. L., J. W. Szostak, and R. J. Rothstein. 1981. Yeast transformation: a model system for the study of recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:6354-6358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porta, A., Z. Wang, A. Ramon, F. A. Muhlschlegel, and W. A. Fonzi. 2001. Spontaneous second-site suppressors of the filamentation defect of prr1Delta mutants define a critical domain of Rim101p in Candida albicans. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:624-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramon, A. M., A. Porta, and W. A. Fonzi. 1999. The effect of environmental pH on the morphological development of Candida albicans is mediated via the pacC-related transcription factor encoded by PRR2. J. Bacteriol. 181:7524-7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rollins, J. A., and M. B. Dickman. 2001. pH signaling in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: identification of a pacC/RIM1 homolog. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:75-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saporito-Irwin, S. M., C. E. Birse, P. S. Sypherd, and W. A. Fonzi. 1995. PHR1, a pH-regulated gene of Candida albicans, is required for morphogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:601-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmitt, E. K., R. Kempken, and U. Kuck. 2001. Functional analysis of promoter sequences of cephalosporin C biosynthesis genes from Acremonium chrysogenum: specific DNA-protein interactions and characterization of the transcription factor PACC. Mol. Genet. Genomics 265:508-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuler, G. D., S. F. Altschul, and D. J. Lipman. 1991. A workbench for multiple alignment construction and analysis. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 9:180-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su, S. S. Y., and A. P. Mitchell. 1993. Molecular characterization of the yeast meiotic regulatory gene RIM1. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:3789-3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suarez, T., and M. A. Peñalva. 1996. Characterization of a Penicillium chrysogenum gene encoding a PacC transcription factor and its binding sites in the divergent pcbAB-pcbC promoter of the penicillin biosynthetic cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 20:529-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tilburn, J., E. A. Sarkar, M. Orejas, J. Mungroo, M. A. Peñalva, and H. N. J. Arst. 1995. The Aspergillus PacC zinc finger transcription factor mediates regulation of both acid- and alkaline-expressed genes by ambient pH. EMBO J. 14:779-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright, W. E., M. Binder, and W. Funk. 1991. Cyclic amplification and selection of targets (CASTing) for the myogenin consensus binding site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:4104-4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]