Abstract

Removal and repair of DNA damage by the nucleotide excision repair pathway requires two sequential incision reactions, which are achieved by the endonuclease UvrC in eubacteria. Here, we describe the crystal structure of the C-terminal half of UvrC, which contains the catalytic domain responsible for 5′ incision and a helix–hairpin–helix–domain that is implicated in DNA binding. Surprisingly, the 5′ catalytic domain shares structural homology with RNase H despite the lack of sequence homology and contains an uncommon DDH triad. The structure also reveals two highly conserved patches on the surface of the protein, which are not related to the active site. Mutations of residues in one of these patches led to the inability of the enzyme to bind DNA and severely compromised both incision reactions. Based on our results, we suggest a model of how UvrC forms a productive protein–DNA complex to excise the damage from DNA.

Keywords: DNA damage, DNA repair, endonuclease, nucleotide excision repair, UvrC, RNase H

Introduction

Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is a conserved DNA repair pathway found in all three kingdoms of life. It is unique in its ability to repair a vast assortment of chemically and structurally distinct DNA lesions. In prokaryotes, the UvrA, UvrB and UvrC proteins mediate NER in a multistep, ATP-dependent reaction. The initial damage recognition is performed by a heterotrimeric UvrA2B complex (Theis et al, 2000) or a heterotetrameric UvrA2B2 complex (Verhoeven et al, 2002b). After damage recognition, UvrA dissociates leaving a stable UvrB–DNA pre-incision complex. UvrC binds to the complex and executes the sequential incision of the damaged DNA strand four nucleotides 3′ and seven nucleotides 5′ of the lesion (Lin and Sancar, 1992a; Verhoeven et al, 2000). UvrC makes stoichiometric incisions, and UvrD (helicase II) is required for removal of the damaged strand and for the productive turnover of UvrC (Caron et al, 1985; Husain et al, 1985). UvrB is believed to remain bound to the DNA until it is displaced by DNA polymerase I, which fills the resulting gap (Orren et al, 1992). The reaction is completed by DNA ligase, sealing the nicked DNA.

UvrC has been shown to catalyze both the 3′ and 5′ incisions, each by a distinct catalytic site that can be inactivated independently (Lin and Sancar, 1992a; Verhoeven et al, 2000; Truglio et al, 2005). The domain responsible for 3′ incision is located in the N-terminal half of the protein and is formed by the first 100 amino acids (Figure 1A). It is homologous in both structure and sequence to the catalytic domain of members of the GIY-YIG endonuclease superfamily (Truglio et al, 2005). Following the 3′ endonuclease domain is a UvrB-interacting region (Hsu et al, 1995) required for 3′ incision (Moolenaar et al, 1998a, 1995), but not for 5′ incision (Moolenaar et al, 1995). The C-terminal half of UvrC contains the catalytic domain responsible for 5′ incision. This domain is followed by two helix–hairpin–helix (HhH) motifs (Aravind et al, 1999), a motif commonly found in nonspecific DNA-binding proteins, which has been observed to interact with the phosphate backbone of the minor groove (Shao and Grishin, 2000; Singh et al, 2002). In UvrC, the tandem HhH motif is essential for 5′ incision and is required for 3′ incision when the lesion resides in certain sequence contexts (Verhoeven et al, 2002a).

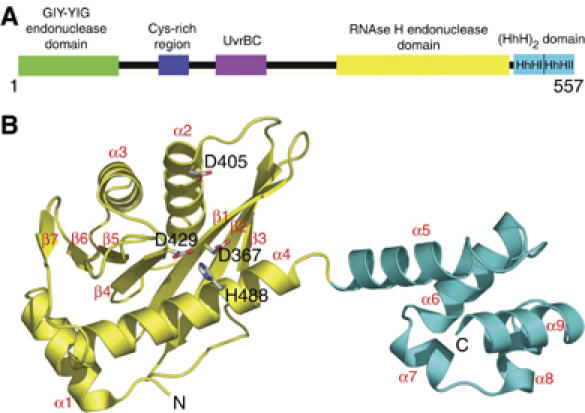

Figure 1.

Overall structure of the 5′ endonuclease and (HhH)2 domain of TmUvrC. (A) Domain architecture of TmUvrC. (B) Structure of UvrCC-term. The endonuclease and (HhH)2 domain are shown in yellow and cyan, respectively. Selected residues are displayed in all-bonds representation. Secondary structure elements and the N- and C-termini are labeled.

We previously solved the structure of the N-terminal endonuclease domain, which provided insights into the 3′ incision reaction (Truglio et al, 2005). In order to obtain a better understanding of the 5′ incision event, we solved the crystal structure of the C-terminal half of Thermotoga maritima UvrC, which includes both the C-terminal endonuclease domain and the (HhH)2 domain. Despite the lack of sequence homology, the endonuclease domain has an RNase H-like fold, which is characteristic of enzymes with nuclease or polynucleotide transferase activities. Based on the structure, various mutations were generated to obtain an understanding of the role of this part of UvrC in the incision reactions.

Results and discussion

Overall structure

Initially, we determined the structure of the 5′ endonuclease domain of UvrC from T. maritima (TmUvrCEndo) consisting of residues 339–502 at a resolution of 1.2 Å (Table I). Subsequently, a larger portion of the protein consisting of the C-terminal 219 amino acids was crystallized (residues 341–557; TmUvrCC-term) at a resolution of 1.5 Å (crystal form 1; Table I). The TmUvrCC-term protein crystallized in four additional crystal forms (crystal forms 2–5; Table I). Crystal form 1 was used for the structural analysis described here, as it was solved at the highest resolution and had the lowest Rfree. The structure consists of the endonuclease domain responsible for the 5′ incision event (residues 341–494), followed by a pair of HhH motifs (residues 497–557) that form an (HhH)2 domain implicated in DNA binding. A very short linker (residues 495 and 496) connects the two domains (Figure 1B).

Table 1.

Crystallization, data collection and refinement statistics

| TmUvrCendo (residues 345–502) | TmUvrCC-term (residues 339–557) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal form (PDB ID) | — | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| (2NRR) | (2NRT) | (2NRV) | (2NRW) | (2NRX) | (2NRZ) | |||

| Crystallization conditions | 2.4 M NaCl, 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 4.6, 0.1 M Li2SO4 | 10% PEG8000, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5 | 15% PEG3000, 0.1 M CHES pH 9.5 | 10% PEG3000, 0.1 M phosphate-citrate pH 4.2 | 1.8 M (NH4)2SO4, 50 mM Tris pH 8.5, 25 mM MgSO4 | 14% PEG 8000, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 10 mM MnCl2 | ||

| Space group molecules in the ASU | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | I222 | P21 | P21 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Unit cell dimensions | a=38.1, | a=35.4, | a=35.5, | a=37.8, | a=35.4, | a=35.4, | ||

| b=46.5, | b=72.8, | b=94.6, | b=105.7, | b=81.0, | b=83.9, | |||

| c=84.5 | c=91.7 | c=132.4 | c=156.6 | c=99.6, | c=100.6, | |||

| β=98.0° | β=99.5° | |||||||

| Data collection and refinement | ||||||||

| Pt derivative | Native | |||||||

| Inflection | Remote | |||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.07249 | 1.07114 | 1.0000 | 1.0090 | 1.0047 | 1.1000 | 1.1000 | 1.0090 |

| Measured reflections | 124 246 | 120 470 | 333 240 | 259 228 | 177 922 | 68 050 | 141 889 | 227 801 |

| Unique reflections | 21 864 | 21 984 | 47 662 | 37 576 | 42 358 | 14 326 | 42 886 | 76 400 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 40–1.9 | 40–1.9 | 40–1.2 | 40–1.5 | 40–1.8 | 40–2.3 | 40–1.9 | 40–2.0 |

| Completeness (%) | 96.9 (72.6) | 97.7 (78.5) | 99.6 (99.2) | 98.0 (97.6) | 99.4 (99.9) | 99.8 (99.9) | 97.2 (94.8) | 98.6 (97.9) |

| Rsym | 0.074 (0.32) | 0.074 (0.33) | 0.067 (0.42) | 0.076 (0.42) | 0.044 (0.35) | 0.111 (0.56) | 0.071 (0.34) | 0.065 (0.42) |

| 〈I〉/〈σI〉 | 30.8 (5.2) | 30.7 (4.9) | 40.2 (3.2) | 24.8 (3.8) | 29.6 (4.7) | 15.0 (3.3) | 18.2 (3.7) | 18.9 (2.6) |

| Phasing to 2.0 Å | ||||||||

| FOM (SOLVE) | 0.43 (0.23) | |||||||

| FOM (RESOLVE) | 0.64 (0.30) | |||||||

| Map correlation | 0.42 | |||||||

| Mean phase difference (deg) | 66.3 (73.4) | |||||||

| Number of atoms | 1320 | 1972 | 3907 | 1803 | 3826 | 3723 | ||

| Rcrys (Rfree) | 0.18 (0.22) | 0.18 (0.22) | 0.18 (0.25) | 0.20 (0.27) | 0.18 (0.24) | 0.18 (0.23) | ||

| R.m.s. deviation bond length (Å) | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.017 | ||

| R.m.s. deviation bond angles (deg) | 1.585 | 1.529 | 1.574 | 1.537 | 1.606 | 1.538 | ||

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | 96.6–3.4 | 94.8–5.2 | 93.4–6.1 | 93.4–4.9 | 93.5–6.2 | 92.1–7.4 | ||

| UvrCEndo (residues 345–502) is the C-terminal endonuclease domain of UvrC. UvrCC-term (residues 339–557) is the C-terminal endonuclease domain of UvrC with the (HhH)2 domain. Values in the highest resolution shell are in parentheses. Rsym=∑hkl ∑i∣Ii−〈I〉∣∑hkl∑i〈I〉, where Ii is the ith measurement and 〈I〉 is the weighted mean of all measurements of I. FOM=∣Fbest∣I∣F∣, with Fbest=∑αP(α)Fhkl(α)/∑αP(α). The map correlation coefficient describes the correlation between the electron density map calculated from the final model and the map corresponding to the experimental set of phases, averaged over all grid points. The mean phase difference is the mean differences between the initial phases calculated from SOLVE and phases calculated from the final wild-type model. Rcryst=∑∣ ∣Fo∣−∣Fc∣ ∣/∑∣Fo∣, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes. Rfree same as Rcryst for 5% of the data randomly omitted from refinement. Ramachandran statistics indicate the fraction of residues in the most favored and additionally allowed regions, respectively, of the Ramachandran diagram as defined by PROCHECK (Laskowski et al, 1993). ASU refers to asymmetric unit. | ||||||||

The endonuclease fold

The core of UvrC's 5′ endonuclease domain has a fold belonging to the RNase H family of enzymes. The fold is also typical of other enzymes with nuclease or polynucleotide transferase activities. The RNase H fold was first observed in 1990 with the crystal structure of RNase HI (Katayanagi et al, 1990; Yang et al, 1990). A similar fold with a related active site has since been identified in retroviral integrases (Rice and Baker, 2001), the PIWI domain of Argonaute (Parker et al, 2004; Song et al, 2004), RuvC (a Holliday junction resolvase) (Ariyoshi et al, 1994; Ceschini et al, 2001), DNA transposases (Lovell et al, 2002), mitochondrial resolvase (Ceschini et al, 2001) and RNase HII (Lai et al, 2000). The closest structural homologues, identified using DALI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/dali), are the core domain of avian sarcoma virus integrase (Z=7.7; PDB entry 1CXQ), the PIWI protein from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Z=7.0; 1W9H), the integrase catalytic domain of HIV-1 (Z=6.1; 1B9D), the PIWI domain of Argonaute from Pyrococcus furiosus (PfAgo) (Z=6.0; 1U04) and RNase HII from Methanococcus janaschii (Z=6.0; 1EKE). The common denominator among all these RNase H-like proteins is an ∼100-residue core structure made up of a five-stranded mixed β-sheet (β1–β5) and three α-helices (α2–α4) (Figures 1 and 2). In TmUvrC, two additional β-strands are accommodated as an insertion within the RNase H-like domain between β5 and α4, completing a central seven-stranded mixed β-sheet (Figure 1). TmUvrC also contains an additional α-helix, α1, located in front of β1, which is oriented perpendicular to and interacts with α4 (Figure 1). Whether this helix is technically a part of the endonuclease domain is not known and requires knowledge of the full-length structure.

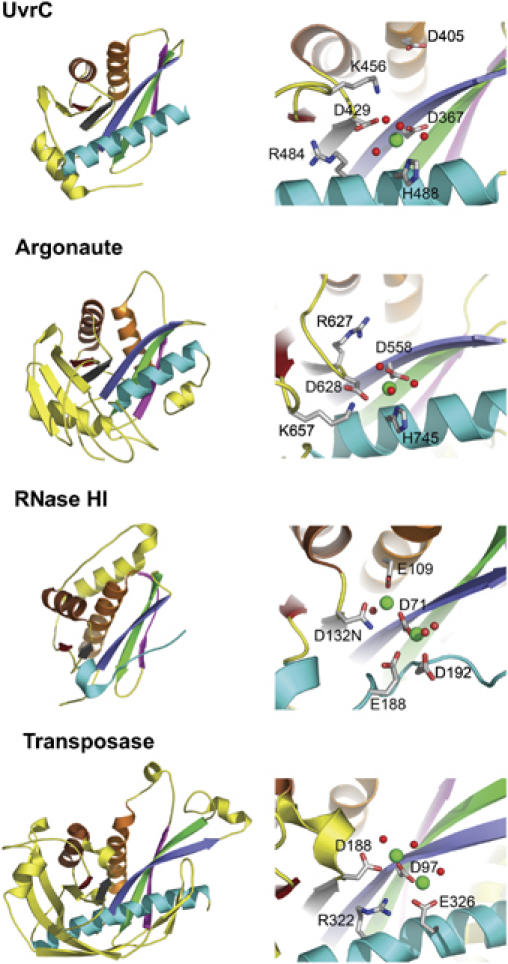

Figure 2.

Comparison of RNase H family members. Domain architecture and active site of T. maritima UvrC endonuclease domain, PIWI domain of P. furiosus Argonaute (PDB ID: 1Z25), B. halodurans RNase HI (PDB ID: 1ZBI) and E. coli Tn5 transposase (PDB ID: 1MUS). The DNA/RNA was omitted from the structures of Tn5 transposase and RNase HI for clarity. Structurally related elements are colored similarly and unrelated elements are shown in yellow. Side chains of selected active site residues are shown in all-bonds representation. Manganese ions and water molecules are shown as green and red spheres, respectively.

UvrC has an uncommon DDH motif

RNase H-related enzymes typically contain a highly conserved carboxylate triad, usually DDE, in their catalytic center (Haren et al, 1999). One of these carboxylates is located on the first β-strand (β1), which is centrally positioned in the β-sheet. The second is located on the fourth β-strand (β4), which borders β1. In TmUvrC, these residues correspond to the strictly conserved D367, on β1 and D429, at the end of β4 (Figure 2). The equivalent aspartates in Escherichia coli UvrC (EcUvrC), D399 and D466, have been shown to be essential for the 5′ incision reaction (Lin and Sancar, 1992a). Site-directed mutagenesis of either aspartate to alanine in TmUvrC severely compromises the protein's ability to perform the 5′ incision. The D367A mutant only incises 1% and D429A 12% the amount of DNA incised by Wt TmUvrC after incubation for 30 min (Figure 3A).

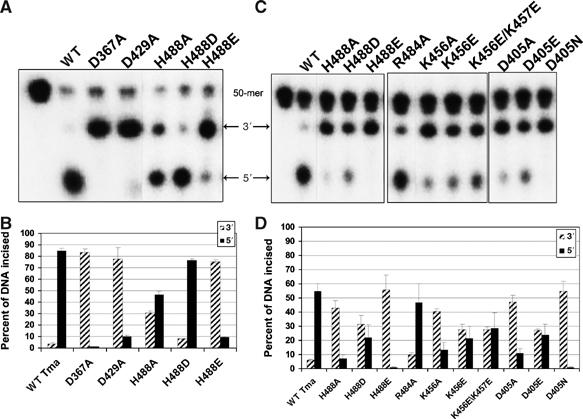

Figure 3.

Incision activity of TmUvrC mutants. (A) The 5′ end-labeled F2650/NDB duplex was incubated with 20 nM Bca UvrA, 100 nM Bca UvrB and 50 nM of the indicated TmUvrC protein for 30 min (A, B) or 5 min (C, D) at 55°C. The reactions were terminated with stop buffer and the incision products were resolved on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. (A, C) Dotted lines indicate that these lanes were not originally next to one another in the original gel. (B, D) Graphical representation of the data in (A) and (C), mean±s.d., n=3 refers to experiments performed on separate days. It is important to note here that UvrC does not turnover, and the incision kinetics represent a single binding event to a UvrB–DNA complex.

The third carboxylate in RNase H-related enzymes varies in its position and is only required to be in proximity to the other two. However, instead of a third carboxylate, TmUvrC contains a highly conserved histidine (H488) on helix α4 in close proximity to the two previously mentioned aspartates (Figure 2). The only other known RNase H family member with a DDH configuration is PfAgo (Figure 2) (Rivas et al, 2005). Site-directed mutagenesis of H488 in TmUvrC produced proteins with reduced catalytic activity. When replaced by an alanine, the amount of 5′ incision product generated after a 30 min incubation was 55% compared with Wt TmUvrC (Figure 3A and B). For the E. coli protein, the equivalent histidine, H538, was changed to phenylalanine, tyrosine, asparagine and aspartate (Lin and Sancar, 1992a). The aromatic substitutions, tyrosine and phenylalanine, rendered the protein unable to perform the 5′ incision, whereas substitution with aspartate and asparagine reduced the 5′ incision activity.

Additional mutants were designed to analyze the importance of the DDH motif relative to the DDD and DDE configuration. In order to better observe the phenotypes of these mutants, incision was monitored at 5 and 30 min. The H488D mutant mimics the few UvrC proteins with a DDD configuration and the active site found in RNase HI. This mutant has a reduced 5′ incision rate and cuts 60% less substrate than Wt TmUvrC after 5 min and 10% less substrate after 30 min (Figure 3). In contrast, the H488E mutant, which mimics the DDE configuration found in Tn5 transposase and the majority of the other RNase H-like enzymes, displays almost no 5′ incision activity after 5 and 30 min of incubation (Figure 3). These results demonstrate the importance of the histidine side chain for UvrC-mediated substrate cleavage. H488 is apparently necessary for the nuclease center, but it is not as important as D367 and D429.

Metal coordination and a model for catalysis

Divalent cations (Mg2+ or Mn2+) are required by RNase H-like enzymes to bind substrate and catalyze nucleotidyl transfer reactions. Stereochemical studies indicate that the reaction occurs by a one-step SN2-like mechanism through the formation of a pentacovalent intermediate and subsequent inversion of the configuration at the phosphate (Kennedy et al, 2000; Krakowiak et al, 2002). A two-metal mechanism was proposed, where one metal acts to lower the pKa of a coordinated water molecule for nucleophilic attack on the scissile phosphate and the other stabilizes the negative charge formed on the pentacovalent intermediate (Steitz and Steitz, 1993). In support of this mechanism, the crystal structure of the Tn5–transposase–DNA complex was observed to contain two divalent metal cations coordinated by the DDE motif (Figure 2) (Lovell et al, 2002). In addition, the crystal structure of Bacillus halodurans RNase H (Bh-RNase H) bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid also contains two divalent cations that are coordinated by the carboxylic triad (Figure 2) (Nowotny et al, 2005).

In order to better understand the catalytic mechanism of the incision reaction catalyzed by the 5′ endonuclease domain of UvrC, we co-crystallized TmUvrCC-term in the presence of 10 mM MnCl2 and collected data to a resolution of 2.0 Å (crystal form 5; Table I). Anomalous difference Fourier and Fo–Fc electron density maps unambiguously reveal one cation in the active site bound solely to the protein through the Nδ of H488 at a distance of 2.5 Å (Figure 2). The two catalytic aspartates, D367 and D429, each interact indirectly with the cation through water molecules. Co-crystallization or soaking at MnCl2 concentrations of 100 mM or higher yielded the same results. As the H488A mutant is still able to perform the 5′ incision, albeit at a somewhat reduced rate (Figure 3), it is unlikely that this residue is solely responsible for metal coordination. In PfAgo, which also contains a DDH catalytic motif, a single manganese is also bound to the active site histidine (Figure 2) (Rivas et al, 2005). However, both catalytic aspartates also directly coordinate the metal. In the case of apo-RNase H from E. coli, two metals were observed in the active site only when Mg2+ concentrations were greater than 10 mM. Otherwise, a single divalent cation was observed. However, the crystal structure of Bh-RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid showed that two divalent cations were positioned in the active site with only 2.5 mM MgCl2 present during crystallization (Figure 2) (Nowotny et al, 2005). This structure suggested that RNase H also uses a conserved two-metal mechanism as proposed for other RNase H-like enzymes. It also showed that binding of the second divalent cation at low ion concentration depended greatly on the presence of nucleic acid substrate. Thus, it was not surprising that only one metal was observed in the TmUvrCC-term structure.

All three residues of the DDD, DDE and DDH motif are in similar positions in Bh-RNase H, Tn5 transposase, PfAgo and TmUvrC (Figure 2). Based on clear active site similarities, it is very likely that, in the presence of DNA, UvrC also binds two divalent cations similar to Bh-RNase H and Tn5 transposase. H488 and D367 of TmUvrC would then coordinate one metal, and D367 and D429 would coordinate the other. To test this hypothesis, each of these residues was mutated individually to alanine. The D367A mutant comprised the most severe phenotype, which would be expected as it is predicted to coordinate both metals simultaneously (Figure 3A and B). Mutant D429A had a more severe phenotype compared to H488A (Figure 3A and B), which suggests that D367 could more strongly compensate for metal binding at the H488 site than for the D429 site.

A possible DDKH motif

Notably, Tn5 contains a highly conserved and catalytically important arginine (R322) in its active site (Figure 2) (Naumann and Reznikoff, 2002). Thus, this enzyme contains a DDRE motif instead of the common DDE motif. In the Tn5/nucleic acid crystal structure, R322 interacts with the phosphate backbone of the DNA (Davies et al, 2000). In TmUvrC, R484 is located in a position similar to R322 in Tn5 and is also conserved (72% in 211 species). PfAgo contains an arginine as well, R627, located at the center of its active site, although its position is different from that of TmUvrC and Tn5 (Figure 2). Surprisingly, mutation of R484 in TmUvrC to alanine does not substantially affect UvrC's activity (Figure 3). However, there is a second positively charged residue located in the active site of TmUvrC, K456, which may be important for catalysis (Figure 2). According to sequence alignments, this residue is strictly conserved with the exception of UvrC from Fusobacterium nucleatum, which contains a glutamate at this position. Mutation of this residue to either alanine or glutamate resulted in a 78 and 61% reduction in 5′ incision, respectively, relative to Wt TmUvrC after 5 min of incubation (Figure 3C and D). These results suggest that UvrC may contain a DDKH motif in its active site. There is also a second, less conserved lysine adjacent to K456. The K456E/K457E mutant had a similar incision activity to K456E alone suggesting that K457 is not important for enzymatic function (Figure 3C and D). The function of K456 is unclear at present, but the charge distribution suggests that it may be involved in stabilizing the transition state or the negatively charged product, thereby making the reaction more favorable.

A unique carboxylate

In addition to the two invariant active site aspartates, UvrC contains a third highly conserved aspartate, D405, which is not found in other RNase H family members and is only substituted by glutamate in Helicobacter pylori UvrC. D405 has previously been shown to be essential for the 5′ incision reaction in EcUvrC (Lin and Sancar, 1992b). Surprisingly, this residue is located at the N-terminus of α2, on the surface of the protein and on the same face as the active site, but approximately 8 Å away from the catalytic center (Figures 1 and 2). Mutation of D405 to alanine in TmUvrC reduces the amount of 5′ incised DNA by 82% compared with Wt TmUvrC after 5 min (Figure 3C and D). A replacement with asparagine is even more severe, almost completely abolishing the enzymatic activity, thus revealing the importance of the side-chain carboxylate for the reaction. We also mutated D405 to glutamate to mimic H. pylori UvrC. This mutant incised 57% less DNA on the 5′ side as compared with Wt TmUvrC after 5 min (Figure 3C and D). Although D405 may not contribute to the catalytic cycle of the enzyme, it could provide a charge repulsion that is used to help to ‘steer' the DNA phosphate backbone down into the active site for cleavage.

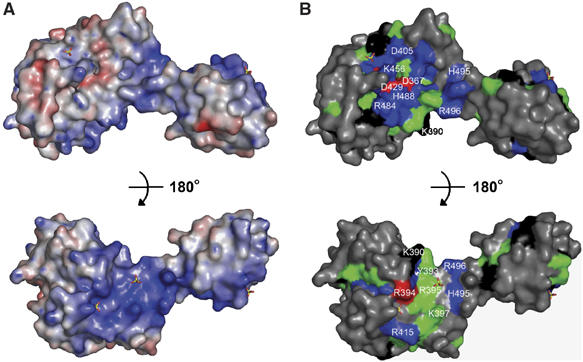

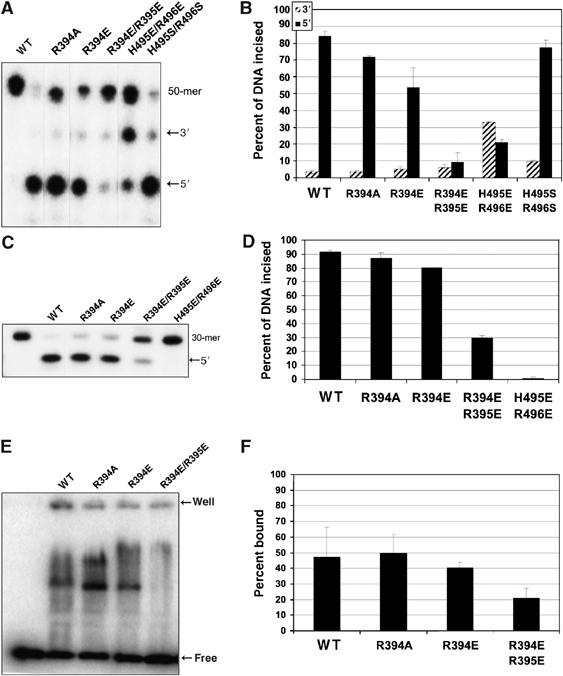

A DNA-binding region important for 3′ and 5′ incision

We identified a positive patch of conserved amino acids on the surface of TmUvrCC-term opposite from the active site; these residues include K390, Y393, R394, R395, K397 and R415 (Figure 4). R394 is strictly conserved and solvent accessible. Crystals of TmUvrCC-term grown in the presence of ammonium sulfate revealed two sulfate molecules bound to this region. One of the sulfates is positioned in a pocket formed by the side chains of R394, Y396, R416, K419 and H420. The other interacts with the highly conserved R395 (Figure 4). We speculate that the bound sulfate molecules mimic the binding of the phosphate backbone of the DNA. In RNase HI, a sulfate molecule was observed in the apo-structure in a similar position as the DNA backbone phosphate in the protein–DNA complex (Nowotny et al, 2005). To test this hypothesis, we generated the R394A and R394E mutants. DNA gel mobility shift assays showed that DNA binding to R394A was similar to that of WT TmUvrC, and binding to the R394E mutant was only slightly reduced. In contrast, DNA binding to an R394E/R395E double mutant was reduced by 44% relative to the total amount of DNA bound by Wt TmUvrC (Figure 5E and F). Analysis of the mutants with respect to their incision activity revealed that 5′ incision is reduced by 15 and 36% compared to Wt TmUvrC for the R394A and R394E mutants, respectively (Figure 5A and B). Interestingly, the R394E/R395E double mutant was not able to make the 3′ incision efficiently, which is a prerequisite for 5′ incision. To determine if 5′ incision was also affected, a fluorescein-containing DNA substrate was synthesized, which contains a nick on the 3′ side of the lesion, where the normal 3′ incision occurs. Such a substrate bypasses the 3′ incision and allows an independent analysis of 5′ incision. The results clearly show that both the R394A and the R394E mutants are mildly reduced in activity (95 and 87% of Wt, respectively) (Figure 5C and D). However, the R394E/R395E double mutant is severely compromised, incising 67% less DNA than Wt TmUvrC after 30 min. Thus, the double mutant is compromised in both incision reactions. These results indicate that this surface region is essential for creating a protein–DNA interface important for incision both on the 3′ and 5′ sides of the lesion.

Figure 4.

Electrostatic surface potential and sequence conservation of the C-terminal half of UvrC. (A) Electrostatic surface potential was calculated with PyMol/APBS and contoured at ±10 kBT. The top panel features the active site of the protein and the bottom view is a 180° rotation. (B) Sequence conservation using the same orientations as in (A). The degree of conservation was obtained by alignment of 47 UvrC sequences with ClustalX. Strictly conserved (red), very highly conserved (blue), highly conserved (green) and moderately conserved (black) amino acids are highlighted. The remainder of the protein is colored in gray. Bound sulfate molecules are shown in all-bonds representation. Selected amino acids are labeled.

Figure 5.

Amino acids R394, R395, H495 and R496 are important for incision. (A) Incision activity. The incubation time was 30 min at 55°C. (B) Graphical representation of the data in (A), mean±s. d., n=3 refers to experiments performed on separate days. (C) The duplex, F19,30/NDB, contains a nick where the normal 3′ incision would occur. It was labeled on the 5′ end of the F19,30 strand so that incision by 20 nM Bca UvrA, 100 nM Bca UvrB and 50 nM of the indicated TmUvrC protein for 30 min at 55°C could be monitored. A representative gel is shown. (D) Graphical representation of data in (C), mean±s.d., n=3 refers to experiments performed on separate days. (E) A representative gel of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay containing 200 nM UvrC and 2 nM NDT/NDB duplex is shown. The indicated protein and DNA were allowed to incubate with DNA for 15 min at room temperature and were then loaded onto a 4% polyacrylamide gel. (F) Quantitation of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay in (E). These data are reported as the mean±s.d. (n=3 refers to experiments performed on separate days).

The (HhH)2 DNA-binding domain

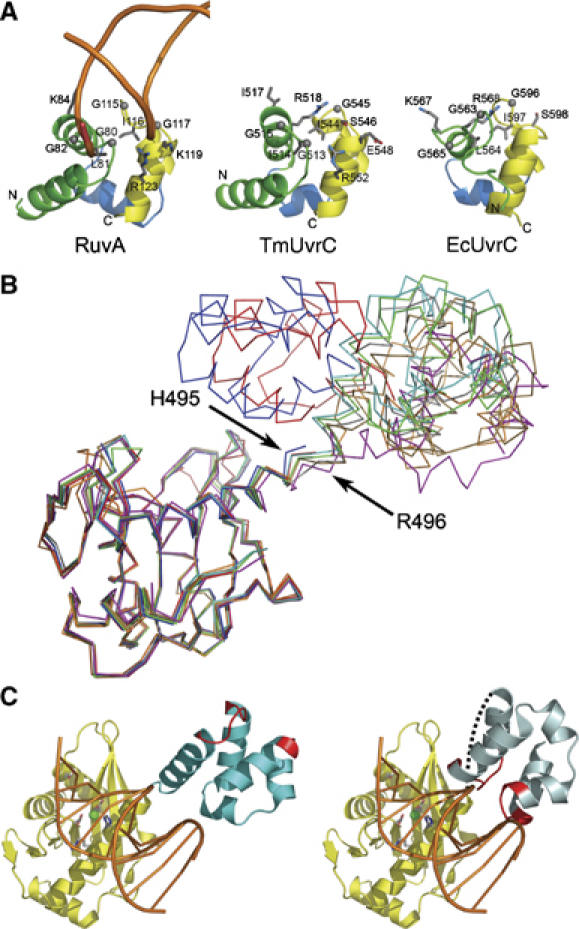

The HhH motif is prevalent in a number of distinct proteins including ERCC1 (Tripsianes et al, 2005), which, together with XPF, is responsible for the 5′ incision in human nucleotide excision repair. It is predominantly involved in nonsequence-specific DNA binding (Doherty et al, 1996; Aravind et al, 1999; Shao and Grishin, 2000). Two of these motifs are found adjacent to each other at the C-terminus of UvrC and are called HhH-I and HhH-II (Figure 1). HhH-I and HhH-II are connected to each other by a small linker helix and are held together as a domain by a conserved hydrophobic core. An NMR structure of the isolated (HhH)2 domain from E. coli has been reported (Figure 6A) (Singh et al, 2002). The EcUvrC and TmUvrC (HhH)2 domains share 40% sequence identity and can be superimposed with a root mean square deviation of 2.0 Å for 43 Cα atoms out of 56. The most apparent difference between the two structures is the absence of the first helix in HhH-I of EcUvrC, which instead forms a loop. This could be due to the analysis of the isolated domain from E. coli (Figure 6A). In the case of EcUvrC, a variant lacking the (HhH)2 domain is not able to bind ssDNA (Moolenaar et al, 1998b). The domain has also been shown to be important for both incision events during NER depending on the sequence context of the lesion (Verhoeven et al, 2002a). Furthermore, the isolated domain from E. coli appears to bind DNA with a centrally located bubble of six or more nucleotides (Singh et al, 2002), which may mimic the form of DNA present in the UvrB/DNA preincision complex (Truglio et al, 2006).

Figure 6.

DNA binding model. (A) Side-by-side comparison of the (HhH)2 domain of RuvA (left), TmUvrC (center) and EcUvrC (right) after superposition. The DNA backbone of the RuvA/DNA complex (left panel) is shown as an orange worm. Selected residues are shown in all-bonds representation and are labeled. The N- and C-termini are indicated. The HhHI and HhHII motifs are colored yellow and green, respectively. The helical linker between the two motifs is colored blue. (B) The endonuclease domains of eight TmUvrCC-term structures are superimposed to show the orientation of the (HhH)2 domains relative to the endonuclease domain in the different crystal forms. (C) Model of TmUvrC interacting with DNA based on a superposition with the Tn5 transposase–DNA complex. The endonuclease and (HhH)2 domain of TmUvrC are colored yellow and cyan, respectively. The DNA is orange and drawn with spokes for clarity. The side chains of the catalytic triad and D405 are depicted as all-bonds. The bound magnesium is shown as a green sphere. In the left panel, the (HhH)2 domain is depicted in the position found in the crystal structure. The DNA-interacting region of the (HhH)2 domain is shown in red. In the right panel, the (HhH)2 domain has been rotated to form a productive UvrC/DNA complex. A dashed line indicates the connection point between the endonuclease domain and the (HhH)2 domain.

Characteristic of HhH motifs is a conserved GφG consensus sequence in the motif's hairpin, where φ is a hydrophobic residue. In UvrC, the sequence is well conserved in the first motif, but degenerative in the second, although a number of UvrC proteins continue to have the GφG consensus sequence in both. TmUvrC has a GIG (G513-I514-G515) sequence in the first hairpin and an IGS (I544-G545-S546) sequence in the second, where the first glycine and the isoleucine have switched places and the second glycine has become a serine (Figure 6A). Looking closer at the rearrangement, the hydrophobic residue (I544) is in a structurally similar position as the central hydrophobic residue in RuvA (I116) and EcUvrC (I597). Residue G545 in TmUvrC is shifted by about 3.4 Å as compared to its counterpart G115 in RuvA and S546 in TmUvrC aligns with the second glycine (G117) in RuvA. The importance of this rearrangement and substitution, if any, is not known. However, the overall importance of the consensus sequence is demonstrated in the crystal structure of the RuvA–Holliday junction (1BDX) where the glycines facilitate a tight approach toward the DNA backbone of duplex DNA in the minor groove (Figure 6A). RuvA also makes additional contacts through positively charged residues in the second helix of each HhH motif. The DNA-interacting surface of the (HhH)2 domain of UvrC from E. coli has been mapped (Singh et al, 2002). The results indicate that like RuvA, UvrC also uses the hairpin regions to interact with DNA. In addition to the hairpin region, RuvA contacts the DNA backbone using K84 in the second helix of the first HhH domain, and K119 and R123 in the second helix of the second HhH domain. Although the positions of R84 and K119 are occupied by I517 and E548, respectively, in TmUvrC, there are a couple of moderately conserved positively charged residues, R518 and R552, in somewhat analogous positions indicating a similar function (Figure 6A). EcUvrC also has two positively charged residues, K567 and R568, in the same position as I517 and R518 of TmUvrC. This suggests that UvrC proteins have evolved slightly different DNA-binding surfaces.

Flexible linker and a DNA-binding model

We were fortunate to solve multiple structures of the C-terminal half of UvrC from five different crystal forms, resulting in eight snapshots of the protein, as some forms had more than one molecule in the asymmetric unit (crystal forms 1–5, Table I). These structures reveal that the position and orientation of the (HhH)2 domain relative to the endonuclease domain can vary significantly (Figure 6B). The rigid-body movements of the (HhH)2 domain are achieved through a flexible linker formed by the highly conserved residues H495 and R496 between the last helix of the endonuclease domain and the first helix of the (HhH)2 domain (Figure 6B). Various other highly conserved residues are also present in the linker adjacent to H495 and R496 including R489, V492 and R499. In six of the eight structures, the (HhH)2 domain is in an extended conformation and bends from side to side over a range of approximately 30° with various degrees of rotation (Figure 6B). However, in two of the structures, the (HhH)2 domain and the endonuclease domain come in close proximity to each other (Figure 6B, the structures depicted in red and blue). In both of these structures, residues 497–502 of the first helix of the (HhH)2 domain are disordered (Figure 6B). We hypothesize that the flexibility of the linker and the subsequent helix is of biological significance during NER. A similar situation was observed for the XPF complex in eukaryotic NER, which is also responsible for 5′ incision and contains an (HhH)2 domain. It should be mentioned that the endonuclease domain of XPF is not similar to that of UvrC. In XPF, the (HhH)2 domain was shown to adopt different orientations in the presence and absence of bound DNA (Newman et al, 2005).

To further investigate the role of the linker, we mutated both H495 and R496 to glutamate or serine. The H495S/R496S double mutant displays a mild phenotype, cutting only 8% less DNA than Wt TmUvrC after 30 min (Figure 5). In contrast, the H495E/R496E double mutant appeared to be severely compromised in 3′ incision (Figure 5), and by using a substrate containing a nick at the 3′ incision position, we observe that it is devoid of 5′ incision activity (Figure 5C and D). It is likely that H495 and R496 will be in close proximity to the DNA during the incision reaction, as they are relatively close to the active site. Thus, putting a negative charge on these residues could interfere with the binding of DNA. Interestingly, some 5′ incision activity can be observed when the non-nicked substrate is used (Figure 5A and B). One possibility is that there is a special link between the 3′ and 5′ incision reactions that results in proper orientation of the DNA in the 5′ active site, regardless of the mutations in certain instances. This hand-off may not occur when the pre-nicked substrate is used, making DNA binding to the 5′ active site more difficult.

RNase H family members recognize dramatically different substrates despite a highly conserved active site. For example, Argonaute recognizes RNA duplexes between an ∼20-mer siRNA and a longer mRNA, while cleaving the mRNA in the middle of the duplex region; RuvC recognizes Holliday junctions, resolving it into two DNA complexes; and retroviral integrases and transposases like Tn5 recognize specific sequences at donor DNA ends, cleave the ends from flanking sequences and insert them into a target site. As UvrC also interacts with DNA, and its active site is more closely related to Tn5 than RNase H, we superimposed the UvrC structure with the Tn5–DNA complex. The protein portion of the Tn5–DNA complex was then removed resulting in a simple model of how the 5′ endonuclease domain of UvrC might interact with DNA (Figure 6C). In the initial model, the DNA-binding site of the (HhH)2 domain faces away from the minor groove of the DNA (Figure 6C, left panel). The RuvA–Holliday junction complex was then used to model how the (HhH)2 domain would interact with the DNA. In order to accommodate such an interaction, the (HhH)2 domain of TmUvrC had to be rotated almost 180° (Figure 6C, right panel). Such a rotation could be easily achieved owing to the inherent flexibility of the linker and thus a simultaneous interaction of the endonuclease domain and the (HhH)2 domain can be envisioned. A model for the predicted DNA binding region on the back of the endonuclease domain is currently not possible as the conformation of the DNA after 3′ incision is entirely unknown. A model could be envisioned in which the DNA wraps around UvrC in the context of the UvrB/UvrC/DNA complex. However, more data are required to make such a prediction.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

UvrC constructs UvrCendo (residues 345–502) and UvrCC-term (residues 339–557) from T. maritima were cloned into the pTXB1 vector (New England Biolabs) and transformed into BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL cells. The expressed proteins were affinity-purified using the IMPACT (NEB) system, followed by size-exclusion chromatography. The proteins were concentrated to 14 mg/ml for UvrCendo and 25 mg/ml for UvrCC-term, based on a molar absorption coefficient of 8960 M−1 cm−1 for both.

Crystallization and data collection

We initially obtained crystals of TmUvrCendo by vapor diffusion, mixing and equilibrating equal volumes of protein solution and precipitant solution containing 2.4 M NaCl, 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.6) and 0.1 M Li2SO4 against a reservoir solution containing 2.65 M NaCl, 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.6) and 0.1 M Li2SO4. Subsequently, five different crystal forms of TmUvrCC-term were obtained by vapor diffusion, mixing and equilibrating equal volumes of protein solution with the appropriate precipitant solution listed in Table I against a reservoir solution similar to the respective precipitant solution with the addition of 250 mM NaCl. All crystals were cryoprotected by passing them stepwise through their respective precipitant solution with added glycerol in increasing incremental steps of 5%, until a final glycerol concentration of 30% was reached. The crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen and diffraction data were collected at beam lines X26C and X12B at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratories. Diffraction data were indexed, integrated and scaled using the HKL2000 software (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997).

The structure of TmUvrCendo was determined by MAD phasing using a crystal soaked in 10 mM K2PtCl4 for 1 h. Phases were calculated using SOLVE (Terwilliger and Berendzen, 1999), and seven Pt sites were identified. Phase refinement was performed with RESOLVE (Terwilliger, 2000), at a resolution of 2.0 Å. The structure was predominantly built using ARP (Perrakis et al, 1999) and the remainder was built using O (Jones et al, 1991). Refinement was carried out with REFMAC (Murshudov et al, 1997). All other structures of TmUvrCC-term were solved by molecular replacement (MOLREP) using the TmUvrCendo structure as the search model (Vagin and Teplyakov, 1997) and refined with REFMAC.

Mutagenesis

TmUvrC mutants were generated with the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using pTXB1-TmUvrC as template, and sense and antisense oligonucleotides specific for each mutant as PCR primers.

DNA substrates and UvrABC incision assay

The DNA substrates were prepared and the incision assays were performed essentially as described previously (Truglio et al, 2005). Briefly, the 5′ or 3′ end-labeled duplex DNA (2 nM) was incised by the UvrABC enzymes (20 nM Bacillus caldotenax (Bca) UvrA, 100 nM Bca UvrB, 50 nM Tma UvrC in 20 μl of UvrABC buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP and 5 mM DTT)) at 55°C for 5 or 30 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of EDTA (20 mM), a stop buffer. A 2 μl portion of the reaction was added to 5 μl of formamide and blue dextran, and then heated to 85°C for 10 min. The incision products were resolved on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresis was performed at 325 V for 40 min in Tris–borate–EDTA buffer (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid and 2 mM EDTA). The gels were dried and exposed to a phosphorimager screen (Molecular Dynamics) overnight. The incision efficiency was calculated using the Molecular Dynamics software ImageQuant. All oligonucleotides were synthesized and PAGE-purified by Sigma Genosys. The F26,50 oligonucleotide has the sequence 5′-GAC TAC GTA CTG TTA CGG CTC CAT C[FldT]C TAC CGC AAT CAG GCC AGA TCT GC-3′, where [FldT] denotes the internal fluorescene. The NDT oligonucleotide has the sequence 5′-GAC TAC GTA CTG TTA CGG CTC CAT CTC TAC CGC AAT CAG GCC AGA TCT GC-3′.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The 5′ end-labeled duplex, NDT/NDB (2 nM), was incubated with 200 nM of the indicated TmUvrC protein in electrophoretic mobility shift assay buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM DTT) for 15 min at room temperature. Following incubation, 10 μl of the reaction was loaded onto a 4% native polyacrylamide gel (80:1 acrylamide:bis ratio). The gel and running buffer contained 0.5 × TBE (44.5 mM Tris, 44.5 mM boric acid and 1.25 mM EDTA). The gel was run for 1 h at 100 V, and then dried and exposed to a phosphorimager screen. The percent of DNA bound was calculated by subtracting the percent of DNA that migrated as free DNA from 100. These data are reported as the mean±s.d.; n=3 refers to separate biological experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by a grant from the NIH to CK (GM 070873), from the PEW Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences to CK and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (BVH). The National Synchrotron Light Source in Brookhaven is supported by the DOE and NIH, and beamline X26C is supported in part by the State University of New York at Stony Brook and its Research Foundation. We thank Drs Hong Wang and Mark Melton for help with purification of some of the UvrC mutants.

Accession numbers Coordinates for TmUvrCEndo and the five crystal forms of TmUvrCC-term (Table I) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 2NRR, 2NRT, 2NRV, 2NRW, 2NRX and 2NRZ, respectively.

References

- Aravind L, Walker DR, Koonin EV (1999) Conserved domains in DNA repair proteins and evolution of repair systems. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 1223–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyoshi M, Vassylyev DG, Iwasaki H, Nakamura H, Shinagawa H, Morikawa K (1994) Atomic structure of the RuvC resolvase: a Holliday junction-specific endonuclease from E. coli. Cell 78: 1063–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron PR, Kushner SR, Grossman L (1985) Involvement of helicase-II (UvrD gene product) and DNA Polymerase-I in excision mediated by the UvrABC protein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 4925–4929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceschini S, Keeley A, McAlister MS, Oram M, Phelan J, Pearl LH, Tsaneva IR, Barrett TE (2001) Crystal structure of the fission yeast mitochondrial Holliday junction resolvase Ydc2. EMBO J 20: 6601–6611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DR, Goryshin IY, Reznikoff WS, Rayment I (2000) Three-dimensional structure of the Tn5 synaptic complex transposition intermediate. Science 289: 77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty AJ, Serpell LC, Ponting CP (1996) The helix–hairpin–helix DNA-binding motif: a structural basis for non-sequence-specific recognition of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 2488–2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haren L, Ton-Hoang B, Chandler M (1999) Integrating DNA: transposases and retroviral integrases. Annu Rev Microbiol 53: 245–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DS, Kim ST, Sun Q, Sancar A (1995) Structure and function of the UvrB protein. J Biol Chem 270: 8319–8327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain I, Houten BV, Thomas DC, Abdel-Monem M, Sancar A (1985) Effect of DNA polymerase I and DNA helicase II on the turnover rate of UvrABC excision nuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 6774–6778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A 47: 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayanagi K, Miyagawa M, Matsushima M, Ishikawa M, Kanaya S, Ikehara M, Matsuzaki T, Morikawa K (1990) Three-dimensional structure of ribonuclease H from E. coli. Nature 347: 306–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AK, Haniford DB, Mizuuchi K (2000) Single active site catalysis of the successive phosphoryl transfer steps by DNA transposases: insights from phosphorothioate stereoselectivity. Cell 101: 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowiak A, Owczarek A, Koziolkiewicz M, Stec WJ (2002) Stereochemical course of Escherichia coli RNase H. Chembiochem 3: 1242–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L, Yokota H, Hung LW, Kim R, Kim SH (2000) Crystal structure of archaeal RNase HII: a homologue of human major RNase H. Structure 8: 897–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr 26: 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- Lin J-J, Sancar A (1992a) Active site of (A)BC excinuclease: I. Evidence for 5′ incision by UvrC through a catalytic site involving Asp399, Asp438, and His538 residues. J Biol Chem 267: 17688–17692 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JJ, Sancar A (1992b) Evidence for 5′ incision by UvrC through a catalytic site involving Asp399, Asp438, Asp466, and His538 residues. J Biol Chem 267: 17688–17692 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell S, Goryshin IY, Reznikoff WR, Rayment I (2002) Two-metal active site binding of a Tn5 transposase synaptic complex. Nat Struct Biol 9: 278–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar GF, Bazuine M, van Knippenberg IC, Visse R, Goosen N (1998a) Characterization of the Escherichia coli damage-independent UvrBC endonuclease activity. J Biol Chem 273: 34896–34903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar GF, Franken KL, Dijkstra DM, Thomas-Oates JE, Visse R, van de Putte P, Goosen N (1995) The C-terminal region of the UvrB protein of Escherichia coli contains an important determinant for UvrC binding to the preincision complex but not the catalytic site for 3′-incision. J Biol Chem 270: 30508–30515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar GF, Uiterkamp RS, Zwijnenburg DA, Goosen N (1998b) The C-terminal region of the Escherichia coli UvrC protein, which is homologous to the C-terminal region of the human ERCC1 protein, is involved in DNA binding and 5′ incision. Nuclieic Acids Res 26: 462–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G, Vagin A, Dodson E (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D 53: 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann TA, Reznikoff WS (2002) Tn5 transposase active site mutants. J Biol Chem 277: 17623–17629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M, Murray-Rust J, Lally J, Rudolf J, Fadden A, Knowles PP, White MF, McDonald NQ (2005) Structure of an XPF endonuclease with and without DNA suggests a model for substrate recognition. EMBO J 24: 895–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, Yang W (2005) Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell 121: 1005–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orren DK, Selby CP, Hearst JE, Sancar A (1992) Post-incision steps of nucleotide excision repair in Escherichia coli. Disassembly of the UvrBC–DNA complex by helicase II and DNA polymerase I. J Biol Chem 267: 780–788 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In Methods in Enzymology, Carter CW, Sweet RM (eds) Vol. 276, pp 307–326. New York: Academic Press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JS, Roe SM, Barford D (2004) Crystal structure of a PIWI protein suggests mechanisms for siRNA recognition and slicer activity. EMBO J 23: 4727–4737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol 6: 458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice PA, Baker TA (2001) Comparative architecture of transposase and integrase complexes. Nat Struct Biol 8: 302–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas FV, Tolia NH, Song JJ, Aragon JP, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L (2005) Purified Argonaute2 and an siRNA form recombinant human RISC. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 340–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao X, Grishin NV (2000) Common fold in helix–hairpin–helix proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 2643–2650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Folkers GE, Bonvin AM, Boelens R, Wechselberger R, Niztayev A, Kaptein R (2002) Solution structure and DNA-binding properties of the C-terminal domain of UvrC from E. coli. EMBO J 21: 6257–6266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JJ, Smith SK, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L (2004) Crystal structure of Argonaute and its implications for RISC slicer activity. Science 305: 1434–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz TA, Steitz JA (1993) A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 6498–6502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC (2000) Maxinum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D 56: 965–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J (1999) Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D 55: 849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis K, Skorvaga M, Machius M, Nakagawa N, Van Houten B, Kisker C (2000) The nucleotide excision repair protein UvrB, a helicase-like enzyme with a catch. Mutat Res 460: 277–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripsianes K, Folkers G, Ab E, Das D, Odijk H, Jaspers NG, Hoeijmakers JH, Kaptein R, Boelens R (2005) The structure of the human ERCC1/XPF interaction domains reveals a complementary role for the two proteins in nucleotide excision repair. Structure 13: 1849–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truglio JJ, Karakas E, Rhau B, Wang H, Dellavecchia MJ, Van Houten B, Kisker C (2006) Structural basis for DNA recognition and processing by UvrB. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truglio JJ, Rhau B, Croteau DL, Wang L, Skorvaga M, Karakas E, DellaVecchia MJ, Wang H, Van Houten B, Kisker C (2005) Structural insights into the first incision reaction during nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J 24: 885–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A, Teplyakov A (1997) MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr 30: 1022–1025 [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven EE, van Kesteren M, Moolenaar GF, Visse R, Goosen N (2000) Catalytic sites for 3′ and 5′ incision of Escherichia coli nucleotide excision repair are both located in UvrC. J Biol Chem 275: 5120–5123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven EE, van Kesteren M, Turner JJ, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH, Moolenaar GF, Goosen N (2002a) The C-terminal region of Escherichia coli UvrC contributes to the flexibility of the UvrABC nucleotide excision repair system. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 2492–2500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven EE, Wyman C, Moolenaar GF, Goosen N (2002b) The presence of two UvrB subunits in the UvrAB complex ensures damage detection in both DNA strands. EMBO J 21: 4196–4205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Hendrickson WA, Crouch RJ, Satow Y (1990) Structure of ribonuclease H phased at 2̊ resolution by MAD analysis of the selenomethionyl protein. Science 249: 1398–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]