Abstract

A binary complex of the ammonia channel Amt1 from Methanococcus jannaschii and its cognate PII signalling protein GlnK1 has been produced and characterized. Complex formation is prevented specifically by the effector molecules Mg-ATP and 2-ketoglutarate. Single-particle electron microscopy of the complex shows that GlnK1 binds on the cytoplasmic side of Amt1. Three high-resolution X-ray structures of GlnK1 indicate that the functionally important T-loop has an extended, flexible conformation in the absence of Mg-ATP, but assumes a compact, tightly folded conformation upon Mg-ATP binding, which in turn creates a 2-ketoglutarate-binding site. We propose a regulatory mechanism by which nitrogen uptake is controlled by the binding of both effector molecules to GlnK1. At normal effector levels, a 2-ketoglutarate molecule binding at the apex of the compact T-loop would prevent complex formation, ensuring uninhibited ammonia uptake. At low levels of Mg-ATP, the extended loops would seal the ammonia channels in the complex. Binding of both effector molecules to PII signalling proteins may thus represent an effective feedback mechanism for regulating ammonium uptake through the membrane.

Keywords: electron microscopy, membrane transport, nitrogen metabolism, signalling mechanism, X-ray crystallography

Introduction

Biosynthesis of macromolecules requires reduced nitrogen. Whereas higher eukaryotes usually take up nitrogen in the form of amino acids, the prevalent source for microorganisms is either uncharged ammonia (NH3) or the ammonium ion (NH4+). Free diffusion of ammonia through the membrane is uncontrolled, and it is too slow at low or neutral pH (Kleiner, 1985). Therefore, many microorganisms have evolved systems for highly efficient and strictly regulated ammonium uptake.

Members of the ammonium uptake (Amt) family of membrane proteins are found in bacteria, archaea, fungi and plants. Mammalian homologues are the Rhesus glycoproteins (Marini et al, 1997). The recent high-resolution crystal structures of AmtB from Escherichia coli (Khademi et al, 2004; Zheng et al, 2004) and Amt1 from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Andrade et al, 2005) show that the Amt proteins are trimers, with 11 membrane-spanning helices in the monomer forming a bundle around a hydrophobic channel. The X-ray structures imply that Amt proteins act as channels enabling controlled uptake of ammonia rather than active transport of ammonium ions (Khademi et al, 2004). Each monomer has an ammonium-binding site at the extracellular pore entrance that might deprotonate the ammonium ion for passage through the channel. On the cytoplasmic side, ammonia would again accept a proton at physiological pH to form the ammonium ion.

In the cell, glutamine synthetase adds the ammonium ion to glutamate to produce glutamine. The amino group is then transferred to 2-ketoglutarate (2-KG) for the synthesis of glutamate, from where it enters various anabolic pathways. Thus 2-KG, a central effector molecule in cellular metabolism, is the final acceptor of ammonium nitrogen in the reductive transamination cycle (Reitzer, 2003).

Nitrogen metabolism in archaea and bacteria is regulated by the soluble PII proteins, which are among the most ancient, ubiquitous and versatile signalling proteins (Ninfa and Jiang, 2005). E. coli has two of these proteins: the family prototype known as PII or GlnB and its homologue GlnK (van Heeswijk et al, 1996). They bind the small effector molecules ATP, 2-KG or glutamate (Vasudevan et al, 1994; Kamberov et al, 1995) and form trimers, like the Amt proteins. The molecular mass of PII monomers is ∼13 kDa.

Several crystal structures of PII proteins have been determined with or without bound ATP or ADP (Cheah et al, 1994; Xu et al, 1998, 2003; Benelli et al, 2002; Schwarzenbacher et al, 2004; Sakai et al, 2005; Nichols et al, 2006), but none in complex with Mg-ATP or 2-KG. The PII monomer has an α/β-structure with three loops, one of which, the T-loop, has been implicated in the regulation of uridylyl transfer (Jaggi et al, 1996). In many bacteria, a conserved tyrosine in the T-loop is covalently modified under nitrogen-limiting conditions. In E. coli, this tyrosine is uridylylated, but adenylylation of the same residue has been found in Streptomyces coelicolor (Hesketh et al, 2002) and Corynebacterium glutamicum (Strosser et al, 2004). A cyanobacterial PII has been reported to be phosphorylated at a nearby serine residue (Forchhammer and Tandeau de Marsac, 1994; Jaggi et al, 1996). It is thought that at low cellular nitrogen levels and consequently high concentrations of 2-KG, the latter binds to PII proteins, modulating the activity of a number of enzymes in the nitrogen metabolism pathways (Jiang et al, 1998a, 1998b and 1998c; Atkinson and Ninfa, 1999). Biochemical studies have shown that the binding of 2-KG to E. coli PII is strictly dependent on ATP (Kamberov et al, 1995).

The gene of GlnK in eubacteria and archaea is almost invariably linked to an Amt gene and in many cases, both open reading frames are found on the same operon (Thomas et al, 2000). Thus, it was concluded that GlnK might be involved not only in the regulation of nitrogen metabolism but also of ammonium uptake. A recent study Durand and Merrick (2006) has reported the isolation of a 1:1 AmtB/GlnK complex from E. coli, which dissociated in the presence of ATP, MgCl2 and 2-KG, suggesting a direct role of small effector molecules in the regulation of ammonia uptake. Docking of a homology model of A. fulgidus GlnB1 to the crystal structure of Amt1 from this organism recently resulted in a hypothetical model of a complex in which the T-Loops blocked the ammonia channel (Andrade et al, 2005). The mechanisms by which the PII proteins regulate ammonium uptake through Amt, however, remained unknown.

In the present study, we demonstrate the formation of a binary complex of GlnK1 and Amt1, the homologues of GlnK and AmtB in Methanococcus jannaschii. Mg-ATP together with 2-KG prevents complex formation. We identified the location of GlnK1 in the isolated complex by electron image processing and determined the crystal structures of GlnK1 with and without bound effectors. Together, these structures allow us to propose a molecular mechanism for the regulation of ammonium uptake through Amt by PII proteins.

Results

Amt1 and GlnK1 form a binary complex

To investigate the existence and formation of a complex between Amt and PII proteins, and the role of small effector molecules in regulating ammonium uptake, we cloned Amt and GlnK from the hyperthermophile M. jannaschii, with the expectation that these proteins, and any complex they might form, would be more stable than their E. coli counterparts. M. jannaschii has two sets of genes for Amt and PII like proteins. The two PII genes are each linked to an Amt gene and their products differ by only three residues. GlnK1, encoded by the gene linked to Amt1, has 112 amino acids, of which 53% are identical to E. coli GlnK. M. jannaschii Amt1 has 391 amino acids, with 24% identity to E. coli AmtB and 29% to A. fulgidus Amt1.

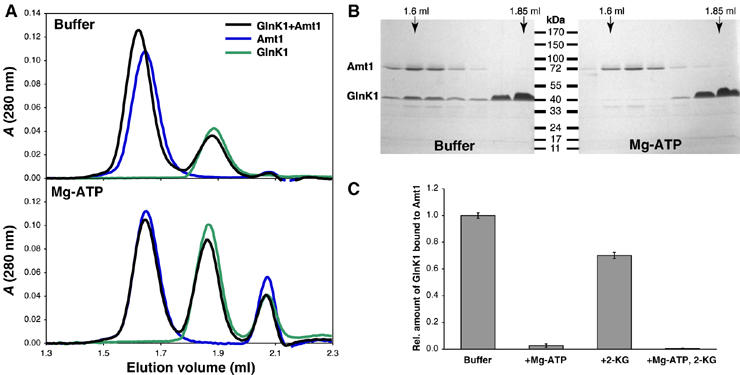

Amt1 and GlnK1 were each expressed in E. coli, purified to homogeneity and analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography. When applied to the column individually, both proteins show a single symmetrical peak upon elution (Figure 1A). When they are mixed and briefly incubated before gel filtration, the Amt1 peak elutes slightly earlier, while the area underneath the GlnK1 peak decreases. Analysis of the peak fractions by Coomassie-stained SDS–PAGE shows clearly that GlnK1 co-elutes with Amt1 (Figure 1B), indicating the formation of a binary complex.

Figure 1.

Size-exclusion chromatography of Amt1 and GlnK1. (A) GlnK1 (green) and Amt1 (blue) applied separately or together (black) to a Superdex 200 PC3.2/30 column, without (top) or with 0.1 mM ATP and 0.5 mM MgCl2 in the elution buffer. In the absence of Mg-ATP, GlnK1 (elution volume ∼1.85 ml) shifts the Amt1 peak (∼1.6 ml) towards lower volumes, indicating the formation of an Amt1/GlnK1 complex. With Mg-ATP present, the Amt1 peak elutes at the same volume with or without GlnK1. The peak at ∼2.05 ml is due to ATP. (B) Peak fractions analyzed by SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining. In the absence of ATP, a significant amount of GlnK1 co-elutes with Amt1. (C) Relative amounts of GlnK1 bound to Amt1 in the presence or absence of Mg-ATP and/or 2-KG. Complex formation was quantified in three separate experiments by Coomassie-stained SDS–PAGE and densitometry, with error bars indicating standard deviations.

Amt1/GlnK1 complex formation is prevented by Mg-ATP and 2-ketoglutarate

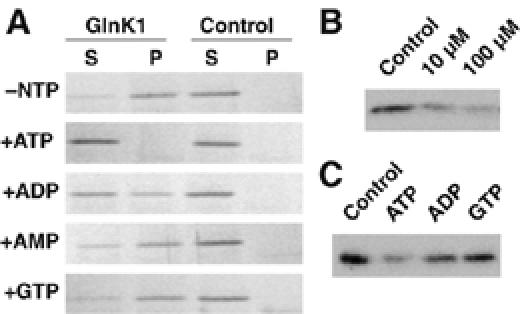

We reasoned that the effectors might be involved in the regulation of ammonium uptake and wondered whether they would affect the observed complex formation. First, we tested ATP, which has been reported to bind tightly to E. coli PII and GlnK. Indeed, the addition of 100 μM ATP and 500 μM MgCl2 reduced the amount of Amt1/GlnK1 complex by ∼95%, as estimated by densitometry of Coomassie-stained SDS gels (Figure 1B). To show that this effect is specific, we performed control experiments with other nucleotides (Supplementary Figure 1A) and confirmed the gel filtration results by co-precipitation experiments. StrepII-tagged GlnK1 was immobilized on streptactin–Sepharose and incubated with purified Amt1 in the presence of different nucleotides. In both experiments, AMP and GTP had no effect, whereas ADP reduced the interaction between Amt1 and GlnK1 only slightly. Thus, we conclude that ATP is required to prevent formation of the Amt1/GlnK1 complex.

It has been observed previously that 2-KG enhances binding of E. coli PII to the downstream signal-transducing kinase/phosphatase NRII in the presence of ATP (Kamberov et al, 1995). In order to investigate whether it also affects the binding of GlnK1 to Amt1, we added 2-KG to the Amt1/GlnK1 mixture before size-exclusion chromatography. Densitometry of Coomassie-stained SDS gels revealed that 2-KG alone reduces the binding of Amt1 to GlnK1 by about 30%, whereas in combination with Mg-ATP, it abolishes complex formation virtually completely (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure 1B).

We confirmed the specificity of GlnK1 for ATP by incubating a biotinylated photo-crosslinkable azido-ATP analogue at 1 μM with 0.15 μM His-tagged GlnK1 and adding either 10 or 100 μM ATP, 100 μM ADP or 100 μM GTP as competitors (Figure 2A). Binding was analyzed on Western blots and detected with streptactin–HRP. Competition with increasing amounts of ATP successively diminished the binding of the labelled nucleotide to GlnK1 (Figure 2B). In contrast, an excess of ADP displaced the biotinylated ATP only partly, whereas GTP had no effect (Figure 2C), consistent with the gel filtration and co-precipitation results.

Figure 2.

Effect of nucleotides on Amt1/GlnK1 complex formation. (A) Co-precipitation: StrepII-GlnK1 bound to streptactin-Sepharose beads was incubated with Amt1 with or without nucleotides present. The bead fraction (P) was separated from the supernatant (S) by centrifugation and the amount of Amt was analyzed by SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining. Association of GlnK1 with Amt1 in the absence of nucleotides (−NTP) is largely abolished by incubation with Mg-ATP. Mg-ADP reduces the association slightly while other nucleotides have no effect. (B) Competition of a biotinylated photo-crosslinkable ATP analogue with increasing amounts of ATP for GlnK1 binding. The decrease in binding of labelled ATP indicates a specific interaction. (C) Competition of a biotinylated photo-crosslinkable ATP analogue with different nucleotides. Whereas unlabelled ATP displaces the biotinylated analogue almost completely, ADP does so only weakly and GTP has no effect, indicating that the nucleotide-binding pocket of GlnK1 is selective for ATP.

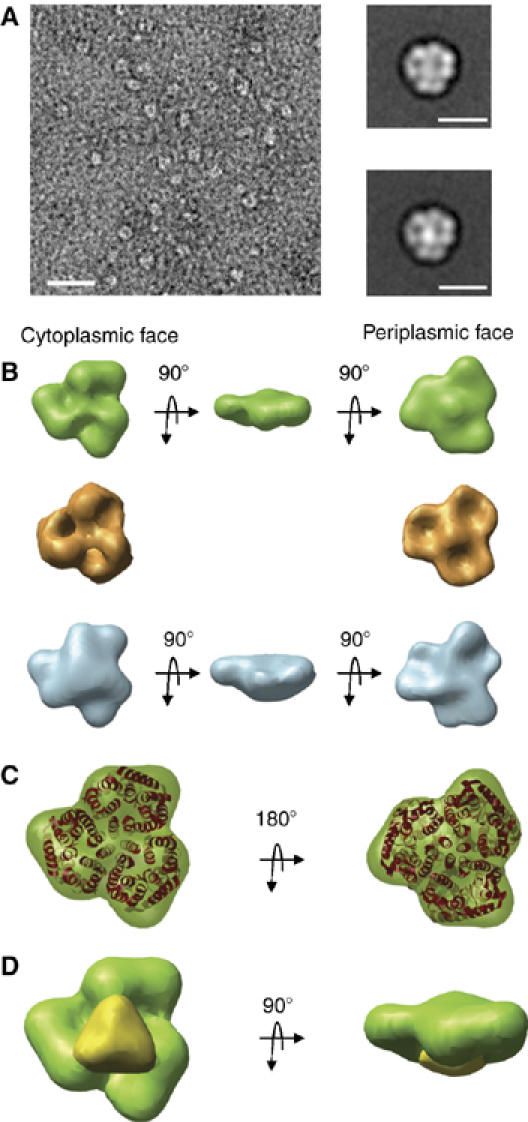

Electron microscopy of the Amt1/GlnK1 complex

We investigated both Amt1 and the Amt1/GlnK1 complex by electron microscopy and single-particle image processing. Negatively stained samples of column fractions showed that both proteins were monodisperse and of similar size (Figure 3A). Representative averages indicated that Amt1 and Amt1/GlnK1 were trimers with a diameter of ∼90 Å in the face-on view. The Amt1/GlnK1 projections had an additional strong density in the center of the trimer. To identify the position of this density in the complex, we calculated three-dimensional (3D) volumes of Amt1 and of Amt1/GlnK1 (Figure 3B). Fourier shell correlation (FSC) with an FSC=0.5 cutoff indicated a resolution of 2.4 nm for the final reconstructions (Supplementary Figure 2). The side views of Amt1 and Amt1/GlnK1 look significantly flatter than the atomic models of Amt trimers would suggest. This is due to specimen dehydration, as expected in negatively stained samples (Ohi et al, 2004). Nonetheless, the triangular shape and lateral dimensions of the 3D volumes closely match those of the A. fulgidus Amt1 trimer in projection (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Electron microscopy and single-particle analysis of negatively stained Amt1 and Amt1/GlnK1 complex. (A) Electron micrograph of Amt1/GlnK1. Scale bar, 100 nm. Insets show representative class averages of Amt1 (top) and Amt1/GlnK1. Scale bars, 10 nm. (B) 3D volumes of Amt1 (green) and Amt1/GlnK1 (blue). The X-ray structure of Amt1 trimer from A. fulgidus (Andrade et al, 2005) converted to SPIDER format and filtered to 20 Å is shown for comparison (gold). (C) Superposition of the A. fulgidus Amt1 X-ray structure (red) and 3D volume of M. jannaschii Amt1. (D) Difference map (yellow) between 3D volumes of Amt1/GlnK1 and M. jannaschii Amt1 (green).

The cytoplasmic and periplasmic surfaces of the Amt1 volume were unambiguously identified by their surface relief, which shows three cavities on the cytoplasmic face and a central protrusion on the periplasmic face, as in the 3D volume calculated for comparison from the X-ray structure of A. fulgidus Amt1 (Figure 3B). A large additional density covering the three cytoplasmic cavities was evident in the Amt1/GlnK1 complex. A difference map between the experimentally determined volumes (Figure 3D) indicated that the extra density is located symmetrically on the Amt1 trimer and matches the shape and dimensions of the GlnK1 trimer (see below). This extra density therefore marks the cytoplasmic location of GlnK1 in the Amt1/GlnK complex.

Crystal structure of GlnK1

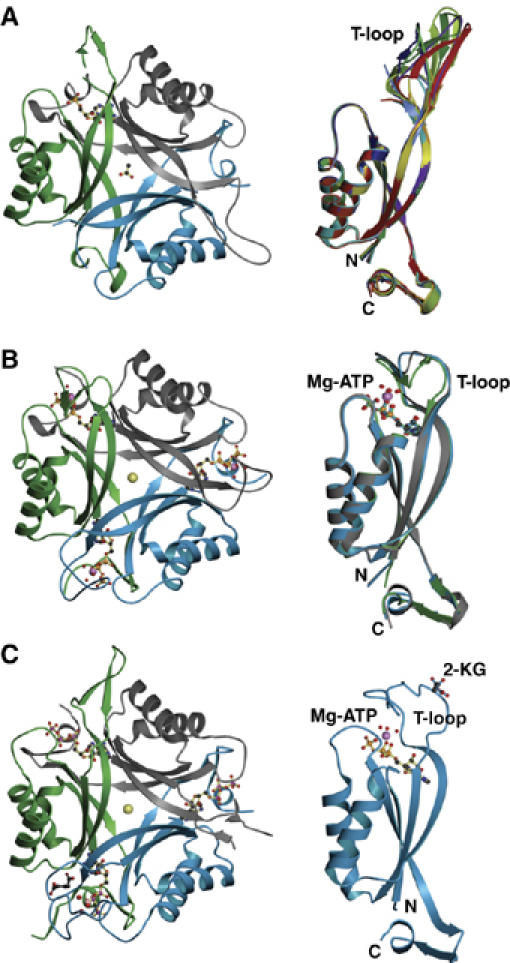

For a detailed understanding of how ATP and 2-KG bind to PII proteins and how this might regulate the interaction with Amt, we crystallized GlnK1 without effector molecules, as well as in complex with Mg-ATP, and with both Mg-ATP and 2-KG present. We then determined the structure of all three forms by molecular replacement with the E. coli GlnB homologue.

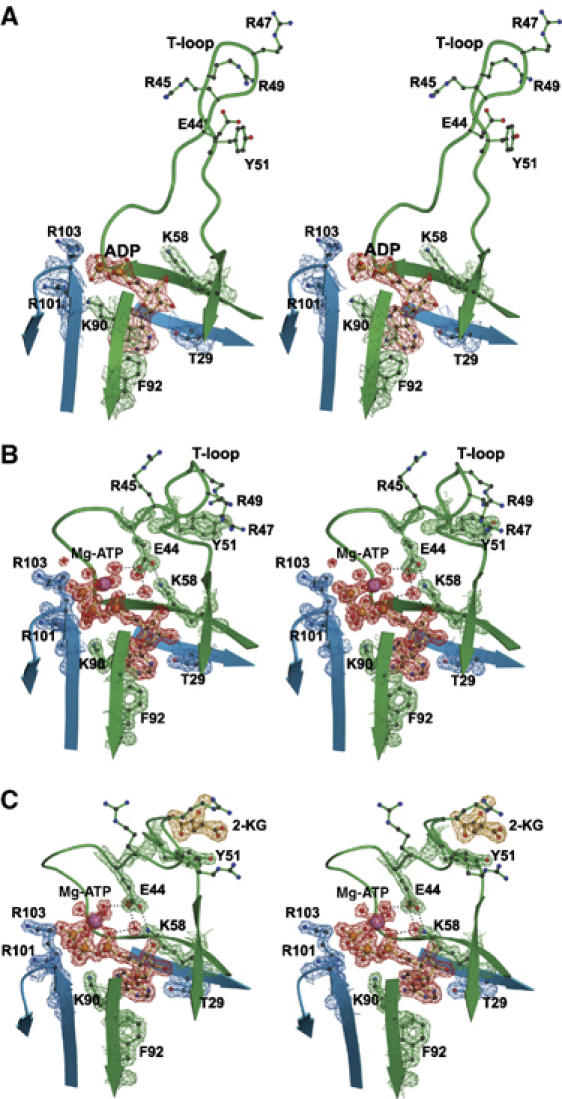

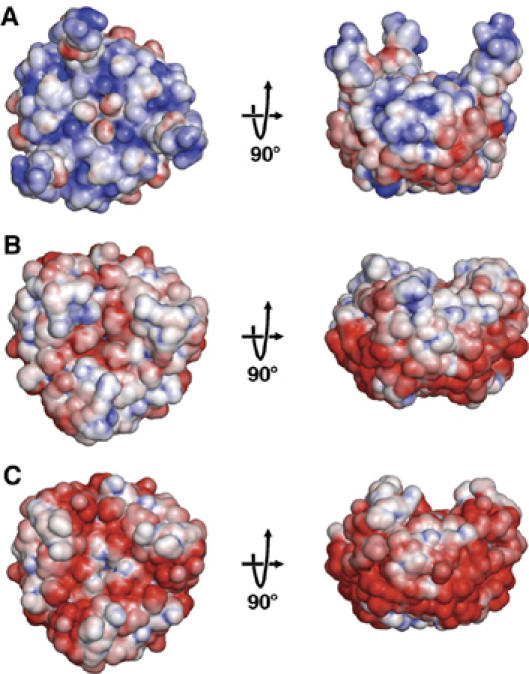

Without added Mg-ATP, GlnK1 crystallized in an orthorhombic form (cell dimensions 96 × 107 × 134 Å3), with crystals diffracting to a resolution of 2.1 Å. The asymmetric unit contained four GlnK1 trimers (Supplementary Figure 3), which differed in the conformation of the T-loop (residues 37–53) as well as in the occupancy of the nucleotide-binding pockets. Six out of the 12 T-loops of the four trimers in the asymmetric unit were disordered, but the other six well-defined loops were built completely into the electron density. All resolved T-loops in the GlnK1 trimer were in an extended conformation (Figures 4A and 5A). Interestingly, their structures differed significantly from one another (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 4), indicating a high degree of flexibility. Although no nucleotides had been added to the crystallization buffer, four of the 12 binding pockets were occupied by ADP (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 3) and one by AMP, apparently carried over from the expressing cells. The remaining seven binding pockets were empty. There was no correlation between the presence of nucleotides and T-loop conformation. Without T-loops and nucleotides, the pairwise root mean square (r.m.s.) deviations between all 12 monomers ranged from 0.16 to 0.73 Å (Supplementary Table 1), indicating that otherwise the four trimers in the asymmetric unit were virtually identical. The calculated electrostatic potential at neutral pH indicated an overall positive charge on the surface interacting with Amt1 and pronounced clusters of positive charge on the tips of the extended T-loops at arginines 45, 47 and 49 (Figure 6A)

Figure 4.

X-ray structures of GlnK1 (A) in the absence of added nucleotide at 2.1 Å; (B) with bound Mg-ATP at 1.2 Å; (C) with Mg-ATP and 2-KG at 1.6 Å resolution. On the left is the trimer with the Amt1 interaction surface facing up. Individual protein monomers are drawn as blue, green and gray ribbon diagrams. Bound cofactors are shown as ball-and-stick models. In (A), one out of three monomers binds ADP; in (B), all three monomers bind Mg-ATP; in (C), all three monomers bind ATP, but only the blue monomer binds Mg2+ as well, plus a single molecule of 2-KG. The center of the trimer holds either an acetate (A) or a chloride ion (yellow sphere). The corresponding monomer side views are shown on the right. (A) Superposition of six monomers with resolved T-loops in the extended conformation (Supplementary Figure 4). (B) Superposition of three monomers of one Mg-ATP-binding trimer, with T-loops in the compact conformation. Color coding as in Supplementary Figures 3 and 4. (C) Single monomer binding Mg-ATP and 2-KG.

Figure 5.

Stereo diagrams showing details of the electron density of T-loop residues and the nucleotide-binding pocket at the interface between two adjacent GlnK1 monomers (blue and green). (A) Without added Mg-ATP, occasional sites are occupied by ADP (red) or AMP from the expressing cells. The T-loop is in an extended conformation, with arginines 45, 47 and 49 and Tyr51at the tip. (B) Mg-ATP (red) fixes the T-loop in the compact conformation through main-chain interactions with the ATP γ-phosphate and hydrogen bonds with Mg-coordinated water molecules, positioning Glu44 to form a salt bridge with Lys58. (C) By fixing the T-loop in its compact conformation, Mg-ATP (red) creates a binding site for 2-KG (yellow) on the far side of Tyr51. The density above the keto oxygen of 2-KG is due to an ordered water molecule.

Figure 6.

Calculated surface potential on GlnK1 at neutral pH, with positive charge density in blue and negative charge density in red. Views of the surface harboring the T-loops are shown on the left. The corresponding side views are shown on the right, with the T-loops facing up. (A) Trimer model of three identical monomers with T-loops in the extended conformation. In the absence of bound nucleotide, the surface is positively charged. Note the blue clusters of arginines 45, 47 and 49 at the tips of the T-loops. (B) Trimer structure of the GlnK1/Mg-ATP complex with all three binding pockets occupied and the T-loops in the compact conformation. Mg-ATP reverses the overall surface potential towards predominantly negative. (C) Trimer model of three identical monomers, each binding one Mg-ATP and one 2-KG. 2-KG changes the surface potential to strongly negative and fully compensates the positive charges of the T-loop arginines.

Crystal structure of GlnK1 in complex with Mg-ATP

When ATP and Mg2+ were added to the crystallization buffer, GlnK1 formed hexagonal crystals (space group P63; cell dimensions 122.7 × 122.7 × 45.5 Å3) that diffracted beyond 1.1 Å. The asymmetric unit contained one GlnK1 trimer, and all residues, including the three T-loops, were well resolved (Figure 4B). In contrast to the extended conformation in the nucleotide-free form, the T-loops in the trimer assumed a compact shape. Slight differences in their structures (Figure 4B) with overall r.m.s. deviations of ∼0.8 Å, which are visible at this high resolution, are due to crystal contacts. All three nucleotide-binding pockets contained ATP in complex with Mg2+. Each Mg2+ coordinates three water molecules, which in turn form hydrogen bridges with the main-chain carbonyls of T-loop residues Val38, Gly40 and Val42. The T-loop also contributes to the Mg-ATP-binding site through the peptide NH of Val38 interacting with the ATP γ-phosphate, and the side-chain carboxyl of Glu44. This is hydrogen-bonded to three water molecules coordinated by Mg-ATP (Figure 5B), and forms a salt bridge with Lys58. In addition, there are numerous other hydrogen bonds between T-loop residues and a network of ordered water molecules in the second coordination shell of Mg-ATP. The side chain of Arg49 is held in a position parallel to the aromatic ring of Tyr51 by π stacking (Figure 5B). Apart from the T-loop and the side-chain conformation of Lys90 that contributes to the Mg-ATP-binding pocket, the structure was indistinguishable from that of GlnK1 without added nucleotides, with average r.m.s. deviations of 0.48 Å without T-loops (Supplementary Table 1).

Calculations of the electrostatic potential at neutral pH indicated that Mg-ATP binding reverses the overall charge on the GlnK1 surface interacting with Amt1 from predominantly positive to slightly negative (Figure 6B). In particular, the positive charge at the tips of the T-loops is partly compensated in the compact conformation.

Crystal structure of GlnK1 in complex with Mg-ATP and 2-ketoglutarate

A further addition of 10 mM 2-KG to the crystallization buffer containing Mg2+ and ATP yielded orthorhombic crystals (cell dimensions 60.4 × 77.8 × 82.2 Å3) with one trimer in the asymmetric unit, diffracting beyond 1.6 Å resolution. All three binding pockets were occupied by ATP (Figure 4C), but surprisingly only one of the ATP molecules bound Mg2+ (Figure 5C). The T-loop interacting with this Mg-ATP is in the compact conformation, whereas the other two T-loops are extended, as in the ATP-free form. This shows clearly that Mg2+ is required to fix the T-loop in its compact state, and that ATP is necessary but not sufficient to bring about this major conformational change. The compact T-loop was fully resolved, as was one of the extended T-loops, whereas the other one was disordered between residues 47 and 50.

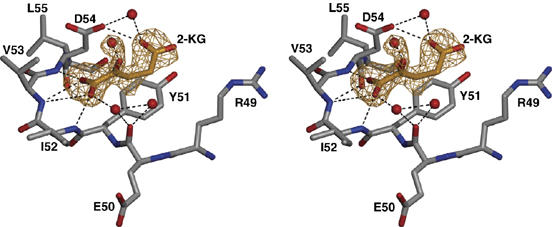

Interestingly, we found a single molecule of 2-KG bound to the compact T-loop interacting with Mg-ATP (Figures 4C, 5C and 7). No other densities in the 1.6 Å map could be attributed to 2-KG. The attachment of 2-KG to GlnK1, thus, requires the compact conformation of the T-loop, which in turn depends on Mg-ATP. The specificity of the 2-KG-binding site is largely provided by a network of hydrogen bonds that link the keto–carboxy group to the main-chain NH of Ile52, Val53 and Asp54. The 5-carboxy group forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Asp54 and interacts by π stacking with the aromatic ring of the conserved Tyr51 (Figures 5C and 7). The polypeptide sequence of the binding site is not strongly conserved because only one side chain is involved in forming hydrogen bonds with 2-KG. The two effector molecules bind at either side of the compact T-loop, so that there are no direct contacts between them.

Figure 7.

Stereo diagram of the apex of the T-loop in the compact conformation with bound 2-KG. An omit map for 2-KG, phased by the unrefined model, is shown at a contour level of three standard deviations (yellow). The keto carboxy group of 2-KG is held in place by hydrogen bonds with three main-chain NH groups. The 5-carboxy group is attached to the carbonyl of Asp54 through hydrogen bonds, one of them via an attached water molecule, and to the coplanar phenyl ring of Tyr51 by π–π interaction.

The conformation of the Mg2+-binding T-loop in this structure corresponds closely to that in the Mg-ATP complex without 2-KG (Figure 5B), except that residues 46–54 are closer to ATP by 0.4–0.7 Å and the side chains of arginines 45, 47 and 49 reorient (Figure 5C). Calculations of electrostatic surface potential indicated that 2-KG further increases the net negative charge on the Amt1 interaction surface of GlnK and fully compensates the positive surface charge of the arginines at the tip of the T-loop (Figure 6C).

Discussion

Formation of the Amt/GlnK complex

It is generally accepted that GlnK and other PII proteins regulate Amt-dependent ammonium uptake in prokaryotes. Until recently, most of the evidence has been based on biochemistry, bacterial physiology and genetics. We show that the Methanococcus proteins form a one-to-one complex of two trimers. The complex can be produced in biochemical quantities in vitro by combining the two protein components expressed in E. coli. Our results demonstrate that Amt1 and GlnK1 interact with each other directly in the absence of Mg-ATP and 2-KG, but the complex does not form in the presence of these two effector molecules. A recent biochemical study on the E. coli AmtB/GlnK complex (Durand and Merrick, 2006) is fully consistent with this finding. In M. jannaschii, but not in E. coli, Mg-ATP by itself largely prevents complex formation. This may be attributable to different binding affinities, or the C-terminal polyhistidine tags on the Methanococcus proteins, which however do not prevent complex formation. Our 3D reconstruction of the complex generated by single-particle analysis of EM images indicates that the GlnK1 trimer binds in the center of the cytoplasmic side of the Amt1 trimer.

T-loop conformation

Our GlnK1 structures show that the functionally important T-loop assumes two distinct main conformations depending on effector binding. In the absence of Mg-ATP, the T-loop has a flexible, extended shape, irrespective of whether the nucleotide-binding site contains ATP, ADP, AMP or water. Whereas ADP has been found before in the nucleotide-binding pocket of PII proteins (Schwarzenbacher et al, 2004), this is not the case for AMP. However, these two nucleotides have not been implicated in the regulation of ammonium uptake, nor do our structures suggest that they participate in this process. Comparison of the eight different conformations of extended T-loops in our GlnK1 structures (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 4) with the seven published structures of other PII proteins with ordered T-loops (Cheah et al, 1994; Xu et al, 1998; Benelli et al, 2002; Xu et al, 2003; Sakai et al, 2005) indicated a high degree of conformational flexibility, but at the same time a preference for the same overall orientation (Figure 4A, Supplementary Figure 4) which may favor association with other proteins, such as Amt.

With Mg-ATP in the nucleotide-binding pocket, the T-loops of Methanococcus GlnK1 assume a compact, rigid conformation, in which they fold tightly against the body of the GlnK1 trimer. The compact T-loop conformation cannot form with ATP alone, as shown by the two extended loops in the GlnK1/Mg-ATP/2-KG complex. Nor would Mg2+ by itself be sufficient to induce the compact conformation, as ATP constitutes an essential part of its binding site, orienting the Mg2+ ion and thereby the network of hydrogen bonds with Glu44, which is strongly conserved. The orientation of Glu44 is critical for establishing the salt bridge to Lys58, which appears to be the key factor in pulling the T-loop into its compact conformation. This salt bridge does not exist in the extended T-loops, even though the orientation of the Lys58 side chain is unchanged.

All previously published crystal structures of PII proteins either had resolved T-loops in the extended conformation without any bound cofactors (Cheah et al, 1994; Xu et al, 1998, 2003; Benelli et al, 2002; Sakai et al, 2005), or bound nucleotides but unresolved, disordered T-loops (Xu et al, 1998, 2001; Schwarzenbacher et al, 2004; Sakai et al, 2005). The disordered T-loops in these structures of ATP-containing PII proteins are evidently owing to the lack of Mg2+ in the crystallization buffer.

2-Ketoglutarate sensing

2-KG, a dianion, binds to GlnK1 at Tyr51 at the apex of the compact T-loop (Figure 5C). Although it has only a minor effect on T-loop structure, it clearly is a strong factor in stabilizing its conformation, being held in place by six hydrogen bonds or water bridges, five of them to the polypeptide main chain. The 2-KG binding site does not exist in the extended T-loop (Figure 5A), but is created only as Mg-ATP fixes the T-loop in its compact conformation. This explains the earlier observation that 2-KG does not bind to E. coli PII unless ATP has bound first (Kamberov et al, 1995).

At physiological ATP levels, a stoichiometry of one molecule of 2-KG per PII trimer has been reported (Kamberov et al, 1995), in striking agreement with our crystal structure. Under different conditions, it is however possible for 2-KG to bind to all three sites in the E. coli protein (Jiang et al, 1998a; Ninfa and Jiang, 2005). 2-KG binding to PII proteins is strongly anti-cooperative, such that the second and third binding sites in the trimer have 20–30-fold lower affinity than the first one to be occupied (Jiang et al, 1998a). This may reflect an increase in negative surface potential, which would make it more difficult for additional copies of 2-KG to bind.

There is growing evidence that the primary function of PII proteins is in sensing the level of 2-KG in the cell (Ninfa and Jiang, 2005; Durand and Merrick, 2006). Concentrations of ATP and 2-KG in M. jannaschii are not known, but for the related M. maripaludis (Dodsworth et al, 2005) a 2-KG level of 0.1 mM has been reported, and for another archaeon, Halobacterium halobium (Michel and Oesterhelt, 1980), an ATP concentration of ∼1 mM is estimated. These values are broadly similar to those found in E. coli, that is, between 0.1 and 0.9 mM for 2-KG, depending on growth conditions, and ∼5 mM for ATP (Rohwer et al, 1996). In vitro, Mg-ATP together with 2-KG prevents the interaction of the phylogenetically distant proteins from E. coli (Durand and Merrick, 2006) or M. jannaschii. This suggests strongly that the mechanism regulating ammonia uptake is conserved among prokaryotes. Our structures of GlnK1 without bound cofactors, in complex with Mg-ATP and with Mg-ATP plus 2-KG now enable us to propose a model for the molecular basis of this elementary signalling process.

Proposed mechanism for the regulation of ammonium uptake by PII proteins

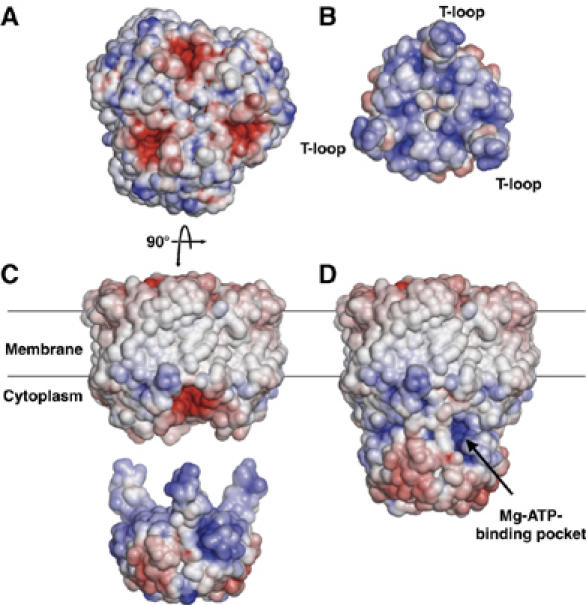

Our structural studies of the Amt1/GlnK1 complex and the Methanococcus GlnK1 protein in three different states offer new insights into the regulation of ammonium uptake through Amt by PII proteins. The experimentally determined volume of the Amt1/GlnK1 complex provided a first, low-resolution framework for docking the GlnK1 structure to the experimentally determined structure of Archaeoglobus Amt1 (Andrade et al, 2005) (Figure 8A). Comparing the Amt1 surface potential to that of GlnK1 (Figure 8B and C), it is striking that the vestibules at the cytoplasmic exit of the ammonia translocation channel are negatively charged, whereas the tips of the extended T-loops of GlnK1 are positively charged. We propose that this charge complementarity would draw the arginines at the tips of the flexible T-loops into the vestibules, sealing the pores, and blocking ammonia uptake in the binary Amt1/GlnK1 complex (Figure 8D). This situation would prevail at low ATP and 2-KG levels, when the cell does not require nitrogen for biosynthesis. Under these conditions, an influx of unused ammonia must be prevented to avoid a rise in intracellular pH, resulting from the uptake of protons by uncharged ammonia. This would tend to reduce the proton gradient used for ATP production, which would be particularly undesirable when energy is sparse.

Figure 8.

Surface potential of the A. fulgidus Amt1 trimer (Andrade et al, 2005) and M. jannaschii GlnK1. Facing views of interacting surfaces of (A) Amt1 with red, negatively charged channel vestibules and (B) GlnK1 with blue, positively charged contact surface and T-loops. (C) Side views of Amt1 in the membrane and a GlnK1 trimer with extended T-loops. (D) Model of the binary Amt1/GlnK1 complex with the T-loops docked into the cytoplasmic pore vestibules. The Mg-ATP-binding pocket on GlnK1 is visible as a dark blue, positively charged cavity.

At increasing ATP levels, Mg-ATP would be attracted to the positively charged binding pockets in the GlnK1 trimer, which are easily accessible on the outside of the binary complex (Figure 8C). Mg-ATP together with 2-KG would fix the T-loops in their compact conformation, so that they would withdraw from the channel vestibules. Simultaneously, the GlnK1 surface facing Amt1 would become negatively charged (Figure 6B), which might cause the Amt1/GlnK1 complex to dissociate by electrostatic repulsion. Both effects would cooperate to unblock the Amt1 channels.

High levels of 2-KG in the cell signal both an ample carbon supply and an increased demand for reduced nitrogen, whereas high levels of ATP indicate sufficient energy for biosynthesis. Our in vitro data, as well as those of Durand and Merrick, show that Mg-ATP and 2-KG together prevent complex formation entirely. The two effectors together are thus likely to function as positive regulators of ammonium uptake in vivo, by interfering with the binding of PII signalling proteins to the Amt channel. This would ensure uninhibited uptake of ammonia, as long as there is an ample supply of both ATP and 2-KG. Note that already one 2-KG bound to GlnK1, as in our structure of the GlnK1/Mg-ATP/2-KG complex, would prevent the effective sealing of all three pores, even if the other two T-loops in the GlnK1 trimer are extended.

Our model of the Amt1/GlnK1 complex resembles the recent in silico model of the Archaeoglobus complex (Andrade et al, 2005). Whereas Andrade et al assumed that the interaction between Amt and PII proteins was largely the result of surface complementarity, our structures suggest that charge complementarity is a key factor, which remains to be demonstrated experimentally. The negative surface potential in the cytoplasmic exit vestibules of Archaeoglobus Amt1 (Figure 8A) and of a Methanococcus Amt1 homology model (not shown) is conspicuous, and at least two of the three matching arginines are conserved in the corresponding archaeal GlnK proteins. Hyperthermophilic archaea may require a particularly strong electrostatic attraction between the pore vestibules and T-loops to overcome thermal motion and ensure a tight seal of the ammonia channels even at 95°C. However, Arg47 at the tip of the T-loop is fully conserved in the PII family, as are two aspartates in the Amt family at the cytoplasmic channel exit. Formation of an Amt/PII complex by charge and surface complementarity, and our proposed mechanism for regulating ammonia uptake through Amt proteins would thus appear to be similar in all organisms.

It is interesting to note the location of the 2-KG-binding site on Tyr51 at the apex of the T-loop, the residue that is reversibly modified in many organisms. Uridylylation or adenylylation of Tyr51 in bacteria, or reversible phosphorylation of a nearby serine in cyanobacteria (Forchhammer and Tandeau de Marsac, 1994; Jaggi et al, 1996; Strosser et al, 2004) all add a covalently attached, negatively charged group at this position, and this apparently prevents the interaction with Amt proteins. A non-covalently attached, negatively charged 2-KG in this position would have the same effect. In addition to fixing the T-loop in its compact conformation, 2-KG thus appears to have another important role in preventing complex formation at high levels of this effector molecule. Our model suggests that binding of 2-KG at Tyr51 is the primary, most ancient step in the regulation of ammonia uptake, and that its role has been taken over by a variety of more permanent, covalent modifications at or near Tyr51 in the course of evolution.

Conclusions

Although it is widely accepted that GlnK proteins regulate Amt-dependent ammonium uptake, the regulatory mechanism and the exact role of ATP and 2-KG in this mechanism has remained enigmatic. We produced a binary complex of the membrane protein Amt1, the M. jannaschii homologue of the E. coli ammonia channel AmtB, with its cognate, soluble PII signalling protein GlnK1, by expressing both in E. coli and combining them in vitro. We show by gel filtration chromatography, co-precipitation and competition experiments that the complex is stable in the absence of Mg-ATP, and Mg-ATP inhibits complex formation, and, together with 2-KG, prevents it completely. Electron microscopy and single-particle analysis indicated that the GlnK1 trimer binds centrally on the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane protein.

To gain detailed insight into the structural basis of the regulatory mechanisms, we determined three high-resolution structures of GlnK1, by itself and in complex with the effector molecules Mg-ATP and 2-KG. We show that, depending on cofactor binding, the T-loop has two distinct conformations, one extended and flexible, the other compact and rigid. The compact conformation is induced by Mg-ATP, but not by ATP alone, and is stabilized by 2-KG. In the absence of both effectors, a tight binary complex between Amt1 and GlnK1 forms, most likely by insertion of positively charged arginines at the ends of the extended T-loops into the negatively charged channel vestibules, which would block ammonia uptake.

At rising ATP levels, Mg-ATP would bind with high affinity to GlnK1, forcing the T-loops into compact conformation and reversing the charge on the interface, which would destabilize the Amt1/GlnK1 complex. The conformational change of the T-loop creates a binding site for 2-KG at Tyr51. This residue is covalently modified in many PII proteins by reversible attachment of a negatively charged group, which ensures nitrogen uptake. A negatively charged 2-KG in this location would have the same effect. Our model suggests how binding of Mg-ATP and 2-KG to PII proteins might regulate nitrogen uptake in prokaryotes by a simple and effective feedback mechanism. It is likely that PII proteins regulate other receptors and signalling pathways in cellular nitrogen metabolism in similar ways.

Materials and methods

Cloning and expression of GlnK1 and Amt1

GlnK1 and Amt1 were expressed with a carboxy-terminal His6-tag using the pET28-D2 vector derived from pET28a (Novagen) by deleting the bases 201–296. Amt1 encoded by the M. jannaschii locus MJ0058 was amplified from the genomic DNA clone AMJGV79 (ATCC #625840) by polymerase chain reaction and GlnK1 on locus MJ0059 was amplified from the clone AMJFT37 (ATCC #625482). Both open reading frames were ligated between the BamH1 and Xho1 sites of the pET28-D2 vector. An N-terminal StrepII-tag on GlnK1 was added between the BamHI and SalI sites of the pASK-IBA7 expression vector (IBA). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

For expression, the Amt1 and GlnK1 plasmids were co-transformed with the plasmid pRARE (Novagen) into the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain (Invitrogen). Bacteria were grown in 2 l shaker cultures in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol to a density of A600 nm=0.6 and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells expressing GlnK1 constructs were incubated for 3 h at 25°C and cells expressing the Amt1 construct for 18 h at 18°C and harvested by centrifugation.

Purification of GlnK1 and Amt1

For isolation of His-tagged GlnK1, cells were resuspended in 5 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) per liter of culture, lysed with 1% w/v Triton X-100 (Sigma) and sonicated with a Branson sonifier 250 for 2 min at 30% output and 50% duty cycle. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation in a Ti70 rotor (Beckman Coulter) for 20 min at 40 000 r.p.m. and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 2 ml of NiNTA resin (Qiagen) per liter of culture. The resin was loaded into a column and washed with 20 volumes of wash buffer (lysis buffer with 20 mM imidazole). His-tagged GlnK1 was eluted with 250 mM imidazole in lysis buffer (elution buffer). Peak fractions were purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Tris–HCl and 100 mM NaCl pH 7.5 and concentrated using a Vivaspin-4 30 000 MWCO ultrafiltration device (Vivascience). StrepII-tagged GlnK1 was purified in the same way except PBS (1.9 mM KH2PO4, 8.2 mM NaH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl and 2.7 mM KCl) was used for lysis and column washes, with streptactin-Sepharose (IBA) as the affinity resin. Beads with bound protein were used directly for co-precipitation and binding assays.

For purification of Amt1, the cells were resuspended in ∼12 ml membrane buffer (50 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM Pefabloc per liter of culture and lysed in a cell disrupter (Constant Systems) at 2.0 bar. Unbroken cells, debris and inclusion bodies were pelleted for 20 min at 14 000 r.p.m. in a JA30.5 rotor (Beckman Coulter). Membranes were collected by centrifugation for 1 h at 45 000 r.p.m. in a Type 45Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter), resuspended in membrane buffer and diluted to a concentration of 2 mg/ml, as judged by a Bradford assay (Sigma Aldrich). Amt1 was solubilized by slow addition of n-decyl-β-D-maltoside (DM; Glycon) to a final concentration of 1.1% (w/v). After stirring for 1 h at room temperature, the solution was clarified for 1 h at 45 000 r.p.m. in a 45Ti rotor and incubated with 1 ml Ni-NTA resin per 100 mg of membranes for 1 h at room temperature. The resin was poured into a column and washed with 7 column volumes of wash buffer (see above) containing 0.2% DM. Amt1 was released with elution buffer containing 0.2% DM. The peak fractions were further purified by ion-exchange chromatography on a MiniQ column (GE Healthcare) in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 0.2% DM with a 0–200 mM NaCl gradient.

Analytical size-exclusion chromatography

The purified proteins were analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography using a SMART system on a Superdex 200 PC3.2/30 column (GE Healthcare) with a void volume of ∼0.8 ml and a total volume of ∼2.3 ml at 25°C at a flow rate of 50 μl/min in binding buffer (50 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl) with 0.2% DM, pH 7.5. Nucleotides and/or 2-KG were added at a concentration of 0.1 mM. When nucleotides were present, 0.5 mM MgCl2 was included. Before each run, the proteins were incubated at room temperature for 5 min at 0.45 mg/ml each, resulting in a three-fold molar excess of GlnK1, with nucleotides and/or 2-KG at two-fold higher concentration than in the running buffer. Fifty microliter fractions between elution volumes 1.55 and 1.90 ml were analyzed by SDS–PAGE using 4–20% acrylamide gradient gels and stained with Coomassie G-250 (Serva). To avoid aggregation of Amt1 at 97°C, the fractions were incubated at 45°C for 10 min in the SDS sample buffer before electrophoresis. Gels were scanned and protein levels estimated densitometrically using the NIH Image 1.63 software. The ratio of the average densities of the GlnK1 bands and the Amt1 bands collected between elution volumes 1.55 and 1.75 ml from three independent experiments was determined. The amount of association in the absence of 2-KG and ATP was defined as 1, and all other values obtained for binding were related to this standard.

Co-precipitation

Amt1 (0.125 mg/ml) was incubated with 10 μl StrepII-GlnK1-Sepharose in 20 mM Tris–HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 0.2% DM, pH 7.0, in a total volume of 50 μl with 0.16 mM nucleotide and 4 mM MgCl2 added. The beads were separated from the supernatant by centrifugation and washed twice with 500 μl of buffer. All samples were analyzed by SDS–PAGE using 4–20% acrylamide gradient gels and stained with Coomassie G-250.

Binding of Mg-ATP to GlnK1

The nucleotide specificity of GlnK1 was analyzed by incubation of 0.15 μM purified His6-tagged protein with 1 μM 8-Azido-ATP-2′,3′-biotin (Affinity Labelling Technologies), followed by incubation with 10 or 100 μM ATP, 100 μM ADP or 100 μM GTP for 20 min on ice. For crosslinking, samples were UV-irradiated at 295 nm for 5 min on ice. Photo-crosslinked proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE on 4–20% acrylamide gradient gels, transferred to nitrocellulose and visualized using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptactin (IBA) and ECL reagent (GE Healthcare).

Electron microscopy and image processing

Amt1 and Amt1/GlnK1 complex from gel filtration peak fractions were diluted to 0.01 mg/ml in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 0.2% (w/v) DM and negatively stained with 0.75% (w/v) uranyl formate (Ohi et al, 2004). Electron micrographs were recorded with an FEI Tecnai T12 electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. Images were taken at a magnification of × 52 000 and a defocus of ∼1.5 μm using low-dose conditions. Tilt pairs at 50–60 and 0° tilt for random conical tilt reconstruction (Radermacher et al, 1987) were collected on Kodak SO-163 film and developed for 10 min with full-strength Kodak D-19 developer at 20°C. Electron micrographs were digitized with an SCAI scanner (Zeiss) using a step size of 7 μm. A 3 × 3 pixel averaging yielded a pixel size of 4.0 Å at the specimen. From a total of 30 negatives, 10 051 tilt pairs of Amt1 particles and 11 071 tilt pairs of Amt1/GlnK1 particles were selected interactively using WEB and SPIDER (Frank et al, 1996). The tilt angle of each particle was determined and selected particles were windowed into 64 × 64 pixel images normalized to background level. All 0° images (Amt1 and Amt1/GlnK1) were subjected to 10 cycles of multireference alignment and classified into 50 output classes. Several classes contained only Amt1 particles, whereas other classes included only Amt1/GlnK1 particles.

Images from three similar classes of each subset were merged. Tilt images of the 3597 Amt1 particles and 2250 Amt1/GlnK1 particles were used to calculate initial 3D reconstructions by back-projection, back-projection refinement and angular refinement. The defocus of each particle was deduced from its position on the micrograph and tilt angles and defocus values determined with CTFTILT (Mindell and Grigorieff, 2003). The contrast transfer function was corrected and volumes were refined using FREALIGN (Stewart and Grigorieff, 2004), with the final SPIDER volumes as input. Fourier shell correlation with an FSC=0.5 criterion indicated a final resolution of 24 Å for both reconstructions. A difference map between the Amt1/GlnK1 and Amt1 volumes was calculated in SPIDER.

3D crystallization

Initial 3D crystallization trials were carried out in 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5) in Greiner 96 three-well sitting-drop plates using commercial crystallization screens (Nextal, Hampton, Jena) and a Cartesian pipetting robot at final protein concentrations of 5, 10 and 15 mg/ml and a temperature of 18°C. Conditions yielding crystals were optimized in hanging drops equilibrated at 18°C against 1 ml reservoir solution. GlnK1 without added Mg-ATP crystallized in 5–8 days after mixing 1 μl protein solution with 1 μl of 10% PEG-6000. The GlnK1/Mg-ATP crystallized within 1 day after mixing 1 μl protein solution containing 5 mM ATP and 20 mM MgCl2 with 1 μl of 10% PEG-6000 in 100 mM Na-acetate (pH 4.6). Crystals of the GlnK1/Mg-ATP/2-KG complex grew within 8–10 days upon mixing 1 μl protein solution containing Mg-ATP as above plus 10 mM 2-KG with 1 μl 2.5% PEG-4000 in 100 mM Na-acetate (pH 4.6).

Data collection, structure determination and refinement

Crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Crystals grown without Mg-ATP were transferred to 25% PEG-400 before freezing. For crystals of GlnK1 in complex with Mg-ATP, or with Mg-ATP and 2-KG, PanatoneN was used as a cryoprotectant. Native data sets of GlnK1 crystals were collected at 100 K on beamline ID14-1 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble/France. Data of the GlnK1/Mg-ATP complex were collected at beamline PXI, and of the GlnK1/Mg-ATP/2-KG complex at PXII of the Swiss Light Source (SLS) in Villigen/Switzerland. All data sets were processed with XDS (Kabsch, 1993) and analyzed with programs from the CCP4 suite (Collaborative Computational Project, 1994).

The structure of the GlnK1/Mg-ATP complex was determined by molecular replacement with Phaser (McCoy et al, 2005) using the coordinates of E. coli GlnB with the T-loops removed. After rigid-body refinement, the GlnK1 model was rebuilt, completed with COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and subjected to iterative rounds of refinement using REFMAC (Murshudov et al, 1997). The solvent model was improved with ARP/wARP (Perrakis et al, 2001), and the structure was validated with COOT and PROCHECK from the CCP4 suite (Table I).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | GlnK1 | GlnK1/Mg-ATP | GlnK1/Mg-ATP/2-KG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 | P63 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | a=96.6, b=107.0, c=134.3, α=β=γ=90° | a=b=122.7, c=45.5, α=β=90°, γ=120° | a=60.4, b=77.8, c=82.2, α=β=γ=90° |

| Resolution (Å) | 20–2.1 (2.2–2.1) | 15–1.2 (1.25–1.2) | 20–1.6 (1.7–1.6) |

| Wavelength (Å) | λ=0.934 | λ=0.9001 | λ=0.9765 |

| Rmerg (%) | 16.0 (53.0) | 12.4 (51.3) | 3.3 (16.8) |

| I/σI | 11.3 (3.1) | 9.7 (2.3) | 27.8 (8.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.0 (98.8) | 99.5 (99.4) | 92.0 (57.7) |

| No. of observed refl. | 370 014 (47 734) | 830 117 (79 028) | 451 557 (32 237) |

| No. of unique refl. | 80 980 (10 355) | 121 571 (13 903) | 47 704 (4 915) |

| Refinement | GlnK1 | GlnK1/Mg-ATP | GlnK1/Mg-ATP/2-KG |

| Resolution (Å) | 19.8–2.1 | 14.6–1.3 | 19.9–1.62 |

| No. of unique reflections | 76 930 | 91 351 | 45 308 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 20.67/26.50 | 14.33/18.69 | 14.67/19.95 |

| No. of atoms in AU | 10 840 | 3428 | 3321 |

| Protein | 9991 | 2820 | 2815 |

| No. of water molecules | 694 | 487 | 393 |

| B-factor (Å2) | 30.3 | 14.9 | 17.4 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | 0.022 | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (deg) | 1.446 | 2.068 | 1.636 |

Figures were generated using the programs PovScript+ (Fenn et al, 2003), PyMOL (Delano, 2004) and POV-Ray (http://www.povray.org). Electrostatic surface potentials were calculated with the APBS plugin (Baker et al, 2001) in PyMOL. The charges for APBS were calculated at different pH with the python script pdb2pqr using CHARMM force fields. Superpositions were carried out with the SSM Superposition routine (Krissinel, and Henrick, 2004) in COOT.

Atomic coordinates of GlnK1 without added nucleotide (2j9d), with bound Mg-ATP (2j9c) and with bound Mg-ATP and 2-KG (2j9e) have been deposited in the PDB.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Figure 4

Supplementary Table 1

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Ziegler for stimulating discussions, RK Hite for help with EM and image processing, T Walz for advice on image processing, Anke Terwisscha van Scheltinga for help and advice on data collection and processing, and the beam line staff at ESRF and the SLS for excellent facilities and assistance.

References

- Andrade SL, Dickmanns A, Ficner R, Einsle O (2005) Crystal structure of the archaeal ammonium transporter Amt-1 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14994–14999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson MR, Ninfa AJ (1999) Characterization of the GlnK protein of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 32: 301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA (2001) Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10037–10041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelli EM, Buck M, de Souza EM, Cruz LM, Pedrosa FO (2002) Herbaspirillum seropedicae signal transduction protein PII is structurally similar to the enteric GlnK. Eur J Biochem 269: 3296–3303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah E, Carr PD, Suffolk PM, Vasudevan SG, Dixon NE, Ollis DL (1994) Structure of the Escherichia coli signal transducing protein PII. Structure 2: 981–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project N (1994) The Ccp4 suite—programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D 50: 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delano WL (2004) Use of PYMOL as a communications tool for molecular science. Abstr Papers of the Am Chem Society 228: U313–U314 [Google Scholar]

- Dodsworth JA, Cady NC, Leigh JA (2005) 2-Oxoglutarate and the PII homologues NifI1 and NifI2 regulate nitrogenase activity in cell extracts of Methanococcus maripaludis. Mol Microbiol 56: 1527–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand A, Merrick M (2006) In vitro analysis of the Escherichia coli AmtB–GlnK complex reveals a stoichiometric interaction and sensitivity to ATP and 2-oxoglutarate. J Biol Chem 281: 29558–29567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D 60: 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn TD, Ringe D, Petsko GA (2003) POVScript+: a program for model and data visualization using persistence of vision ray-tracing. J Appl Crystallogr 36: 944–947 [Google Scholar]

- Forchhammer K, Tandeau de Marsac N (1994) The PII protein in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 is modified by serine phosphorylation and signals the cellular N-status. J Bacteriol 176: 84–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Radermacher M, Penczek P, Zhu J, Li Y, Ladjadj M, Leith A (1996) SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J Struct Biol 116: 190–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh A, Fink D, Gust B, Rexer HU, Scheel B, Chater K, Wohlleben W, Engels A (2002) The GlnD and GlnK homologues of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) are functionally dissimilar to their nitrogen regulatory system counterparts from enteric bacteria. Mol Microbiol 46: 319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggi R, Ybarlucea W, Cheah E, Carr PD, Edwards KJ, Ollis DL, Vasudevan SG (1996) The role of the T-loop of the signal transducing protein PII from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett 391: 223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Peliska JA, Ninfa AJ (1998a) Enzymological characterization of the signal-transducing uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (EC 2.7.7.59) of Escherichia coli and its interaction with the PII protein. Biochemistry 37: 12782–12794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Peliska JA, Ninfa AJ (1998b) Reconstitution of the signal-transduction bicyclic cascade responsible for the regulation of Ntr gene transcription in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 37: 12795–12801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Peliska JA, Ninfa AJ (1998c) The regulation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase revisited: role of 2-ketoglutarate in the regulation of glutamine synthetase adenylylation state. Biochemistry 37: 12802–12810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W (1993) Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Crystallogr 26: 795–800 [Google Scholar]

- Kamberov ES, Atkinson MR, Ninfa AJ (1995) The Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein is activated upon binding 2-ketoglutarate and ATP. J Biol Chem 270: 17797–17807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademi S, O'Connell J III, Remis J, Robles-Colmenares Y, Miercke LJ, Stroud RM (2004) Mechanism of ammonia transport by Amt/MEP/Rh: structure of AmtB at 1.35 A. Science 305: 1587–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner D (1985) Bacterial ammonium transport. Fems Microbiol Rev 32: 87–100 [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E, Henrick K (2004) Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr D 60: 2256–2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini AM, Urrestarazu A, Beauwens R, Andre B (1997) The Rh (rhesus) blood group polypeptides are related to NH4+ transporters. Trends Biochem Sci 22: 460–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ (2005) Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D 61: 458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel H, Oesterhelt D (1980) Electrochemical proton gradient across the cell membrane of Halobacterium halobium: effect of N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide, relation to intracellular adenosine triphosphate, adenosine diphosphate, and phosphate concentration, and influence of the potassium gradient. Biochemistry 19: 4607–4614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Grigorieff N (2003) Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 142: 334–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D 53: 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CE, Sainsbury S, Berrow NS, Alderton D, Saunders NJ, Stammers DK, Owens RJ (2006) Structure of the PII signal transduction protein of Neisseria meningitidis at 1.85 A° resolution. Acta Crystallogr F 62: 494–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninfa AJ, Jiang P (2005) PII signal transduction proteins: sensors of alpha-ketoglutarate that regulate nitrogen metabolism. Curr Opin Microbiol 8: 168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi M, Li Y, Cheng Y, Walz T (2004) Negative staining and image classification—powerful tools in modern electron microscopy. Biol Proc Online 6: 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Harkiolaki M, Wilson KS, Lamzin VS (2001) ARP/wARP and molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr D 57: 1445–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radermacher M, Wagenknecht T, Verschoor A, Frank J (1987) Three-dimensional reconstruction from a single-exposure, random conical tilt series applied to the 50S ribosomal subunit of Escherichia coli. J Microsc 146: 113–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzer L (2003) Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 57: 155–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer JM, Jensen PR, Shinohara Y, Postma PW, Westerhoff HV (1996) Changes in the cellular energy state affect the activity of the bacterial phosphotransferase system. Eur J Biochem 235: 225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H, Wang H, Takemoto-Hori C, Kaminishi T, Yamaguchi H, Kamewari Y, Terada T, Kuramitsu S, Shirouzu M, Yokoyama S (2005) Crystal structures of the signal transducing protein GlnK from Thermus thermophilus HB8. J Struct Biol 149: 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbacher R, von Delft F, Abdubek P, Ambing E, Biorac T, Brinen LS, Canaves JM, Cambell J, Chiu HJ, Dai X, Deacon AM, DiDonato M, Elsliger MA, Eshagi S, Floyd R, Godzik A, Grittini C, Grzechnik SK, Hampton E, Jaroszewski L, Karlak C, Klock HE, Koesema E, Kovarik JS, Kreusch A, Kuhn P, Lesley SA, Levin I, McMullan D, McPhillips TM, Miller MD, Morse A, Moy K, Ouyang J, Page R, Quijano K, Robb A, Spraggon G, Stevens RC, van den Bedem H, Velasquez J, Vincent J, Wang X, West B, Wolf G, Xu Q, Hodgson KO, Wooley J, Wilson IA (2004) Crystal structure of a putative PII like signaling protein (TM0021) from Thermotoga maritima at 2.5 Å resolution. Proteins 54: 810–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Grigorieff N (2004) Noise bias in the refinement of structures derived from single particles. Ultramicroscopy 102: 67–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosser J, Ludke A, Schaffer S, Kramer R, Burkovski A (2004) Regulation of GlnK activity: modification, membrane sequestration and proteolysis as regulatory principles in the network of nitrogen control in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol Microbiol 54: 132–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G, Coutts G, Merrick M (2000) The glnKamtB operon. A conserved gene pair in prokaryotes. Trends Genet 16: 11–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heeswijk WC, Hoving S, Molenaar D, Stegeman B, Kahn D, Westerhoff HV (1996) An alternative PII protein in the regulation of glutamine synthetase in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 21: 133–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan SG, Gedye C, Dixon NE, Cheah E, Carr PD, Suffolk PM, Jeffrey PD, Ollis DL (1994) Escherichia coli PII protein: purification, crystallization and oligomeric structure. FEBS Lett 337: 255–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Carr PD, Clancy P, Garcia-Dominguez M, Forchhammer K, Florencio F, Vasudevan SG, Tandeau de Marsac N, Ollis DL (2003) The structure of the PII proteins from the cyanobacteria Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Acta Crystallogr D 59: 2183–2190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Carr PD, Huber T, Vasudevan SG, Ollis DL (2001) The structure of the PII–ATP complex. Eur J Biochem 268: 2028–2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Cheah E, Carr PD, van Heeswijk WC, Westerhoff HV, Vasudevan SG, Ollis DL (1998) GlnK, a PII-homologue: structure reveals ATP binding site and indicates how the T-loops may be involved in molecular recognition. J Mol Biol 282: 149–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Kostrewa D, Berneche S, Winkler FK, Li XD (2004) The mechanism of ammonia transport based on the crystal structure of AmtB of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17090–17095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Figure 4

Supplementary Table 1