Abstract

BACKGROUND and OBJECTIVES: The close contact between the endothelial cell monolayer in blood vessels and blood plasma allows free diffusion of the hydrophobic unconjugated bilirubin (BR) into these cells. BR can exert both anti- and pro-oxidative effects in various types of cells in a dose-dependent manner. High glucose levels downregulate the expression of the glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) and the rate of glucose uptake in vascular endothelial cell (VEC). Pro-oxidants, on the other hand, up-regulate this system in VEC. We aimed to investigate potential effects of BR on the glucose transport system in VEC. METHODS: Primary cultures of bovine aortic endothelial cells were exposed to BR, and the rate of hexose transport, GLUT-1 expression and plasma membrane localization were determined. RESULTS: BR induced oxidative stress in VEC, and significantly augmented the rate of glucose transport and GLUT-1 expression and plasma membrane localization in these cells. BR also reversed the high glucose-induced downregulation of the glucose transport system in VEC. CONCLUSION: The pro-oxidative properties of BR are responsible for its effects on the regulation of glucose transport in vascular endothelium. Pathological concentrations of BR in the vascular compartment (jaundice) may influence the cellular handling of glucose in diabetes.

Keywords: bilirubin, jaundice, endothelial cells, glucose transport, glucose transporter-1, oxidative stress

Introduction

Unconjugated bilirubin (BR) is an endogenous product of heme degradation. Being a highly lipophilic molecule, BR avidly binds to plasma albumin. It is conjugated in the liver to form water-soluble glucuronides that are excreted in the bile. The “physiological” levels of BR in plasma range between 3 and 15 μmol/l [1]. It has been recognized that BR may exert both cytotoxic and cytoprotective effects in a dose-dependent manner [2], and that cell sensitivity to BR varies among different types of cells. BR-induced encephalopathy due to the pathological accumulation of BR in the plasma of newborns (neonatal jaundice) is the most striking example of the cytotoxic potential of this compound. It involves inhibition of DNA and protein synthesis, altered neurotransmitter synthesis and release, and altered glucose metabolism and mitochondrial functions ([2] and references therein). In addition, it was shown that BR, at a concentration as low as 0.5 μmol/l, induced apoptosis in primary cultures of neurons [3]. Likewise, physiological plasma levels of BR induced death in cultures of cerebral granule neurons [4]. Yet, astrocytes seemed less prone to BR-induced damage at these low levels of BR [5]. Various molecular mechanisms for BR-induced neurotoxicity have been proposed, including mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and cytochrome c release, induction of nitric oxide synthase, and activation of p38-MAPK [2].

Another potential target for BR-induced cytotoxic or cytoprotective effects is the endothelial cell monolayer (tunica intima) in blood vessels. Indeed, it has been reported that BR induced apoptosis in cultured bovine rat endothelial cells at a concentration as low as 10 μmol/l [6]. Such BR-induced cytotoxic effects are of particular interest since lesions in the endothelial cell monolayer in blood vessels precede the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

Cytoprotective effects of BR are attributed to its antioxidant potential due to its free radical scavenging capacity [7, 8]. For example, it has been shown that albumin-bound BR is a scavenger of peroxyl, hydroxyl, hydroperoxyl and superoxide radicals, and protects albumin-bound fatty acids from oxidation [9]. In addition, the ability of BR to inhibit lipid oxidation in low-density lipoprotein has been associated with a reduced risk of atherogenesis [10]. It has also been shown that BR protects VEC from hydrogen peroxide-induced cytotoxic effects [11]. These results support the hypothesis that the antioxidant activity of low levels of BR is associated with a low incidence of cardiovascular disorders. Yet, higher concentrations of BR may exhibit potent pro-oxidant activities that damage cells. Kapitulnik has concluded that BR can exert cytotoxic or cytoprotective effects depending on its plasma concentration and albumin binding capacity, type of target cell, and cellular redox state [2].

Vascular endothelial cells reduce their rate of glucose transport in the face of hyperglycemia, thus protecting their intracellular environment against the deleterious effects of increased production of glucose-derived free radicals and excessive protein glycation [12, 13]. It has also been proposed that pro-oxidants and mitochondrial uncouplers affect the glucose transport in cells. We have shown that VEC and other cell types react to such metabolically challenging conditions by increasing the expression of their typical glucose transporter, GLUT-1, and subsequently augmenting the rate of glucose uptake [14, 15]. The increased influx of glucose serves as a glycolytic substrate for a compensatory ATP synthesis when mitochondrial energy production is impaired in the presence of uncouplers and pro-oxidants. We aimed at investigating whether BR-induced anti- or pro-oxidative effects in VEC modulate the glucose transport system and its autoregulation in VEC.

Materials and methods

Materials

The sources of materials used in this study were as follows: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal calf serum (FCS) from Biological Industries (Beth-Haemek, Israel); 2-[1, 2-3H(N)]-deoxy-D-glucose (2.22 TBq/mmol) from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA); bilirubin (mixed isomers), 2-deoxy-D-glucose (dGlc), HEPES, PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail and streptavidin-agarose beads from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Sulfosuccinimidyl-6-(biotinamido) hexanoate) from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Carboxy-H2DCFDA (5, (and 6)-carboxy-2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate) from Invitrogen-Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). FluoroGuard Antifade reagent from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). All other chemicals, reagents and solvents were reagent- or molecular biology-grade.

Cell culture

Primary cultures of bovine aortic endothelial cells were prepared and characterized as described previously [16]. The cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS. Plates were pre-coated with bovine fibronectin (5 μg/ml phosphate buffered saline (PBS)).

Hexose uptake assay

The [3H]-2-deoxy-D-glucose ([3H]-dGlc) uptake assay in VEC cultures was performed as described [17, 18]. A freshly-prepared stock solution of BR (30 mmol/l) in 100 mmol/l NaOH served to prepare serial dilutions of BR in the NaOH solution. Aliquots from these solutions were added (0.25%, vol/vol) to VEC cultures incubated with DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS and 20 mmol/l HEPES, pH 7.4. The whole procedure was carried out in the dark.

Preparation of cell lysates and Western blot analyses

VEC cultures were lysed for 30 min in an ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mmol/l HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mmol/l NaCl, pH 7.5; 1% Triton X-100 (vol/vol), 2 mmol/l PMSF; and protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100 dilution)), and centrifuged (12,000 rpm in an Eppendorf centrifuge, 15 min, at 4°C). Protein content in the supernatant was determined according to Bradford, using BSA standard dissolved in the same buffer. Aliquots (5-10 μg protein) were mixed with sample buffer (62.5 mmol/l Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 50 mmol/l DTT and 0.1% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue), and warmed at 37°C for 15 min. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE, and Western blot analyses of GLUT-1 was performed using rabbit antiserum prepared against the human erythrocyte transporter (courtesy of Dr. HG Joost, The German Institute for Human Nutrition, Potsdam Rehbrücke, Germany), as described [13].

Cell surface biotinylation and determination of plasma membrane-localized GLUT-1

VEC culture plates were washed with PBS, pH 7.4, and incubated with 0.5 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin in PBS for 30 min at 4°C. The reaction was stopped by rinsing the plates three times with 15 mmol/l glycine in ice-cold PBS. The cells were then collected and solubilized for 30 min on ice in 1 ml solubilization buffer (150 mmol/l NaCl, 50 mmol/l Hepes, pH 7.4, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 2 mmol/l PMSF, 2 μg/ml aprotinin and protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100 dilution)). The supernatant was separated by a 10 min centrifugation in an Eppendorf centrifuge, and mixed with 50 μl streptavidin-agarose beads (1 mg streptavidin/1 ml gel in solubilization buffer containing 0.1 mmol/l PMSF). The suspension was gently mixed for 30 min at 4°C and the beads sedimented by centrifugation. The bead pellet was washed twice with the solubilization buffer and biotinylated proteins were then eluted with urea buffer (8 mol/l urea, 100 mmol/l Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 2% (wt/vol) SDS and 2 mmol/l PMSF). The supernatant was separated from the beads by centrifugation, collected and kept at -70°C until used. Protein content in the supernatant was determined with the BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), using BSA standard dissolved in the same elution buffer. Aliquots from eluates were separated by SDS/PAGE, and Western blot analysis of GLUT-1 was performed as described above.

Determination of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) in VEC cultures

We used the green fluorescence dye 5, (and 6) -carboxy-2' 7'-dichlorodihydrofluoresceine diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA) that is freely permeable to cells. Following its intracellular hydrolysis, its product - carboxy-dichloro-fluoresceine - is retained intracellularly and becomes fluorescent upon oxidation by intracellular oxidants [19]. The dye was freshly dissolved in ethanol, added (20 μmol/l) to VEC grown on fibronectin-coated glass cover slips, and incubated for 1 h. BR was then added at the indicated concentrations, and incubation was carried out for an additional 4-h period. The cells were then washed 3 times with PBS (pH 7.4 at 37°C) and treated with a fixative (4% (wt/vol) formaldehyde in PBS) and 15 μl/cover slip FluoroGuard Antifade reagent. The presence of fluorescent dye in cells was detected (excitation 475 nm; emission 515 nm) with an Axioskop fluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Germany) equipped with a photo camera (Coolsnap, Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ, USA) at x32 magnification. The relative fluorescence intensity in 20 randomly selected fields for each treatment was analyzed and quantified using ImageProPlus software.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± S.E.M.; Student's two-tailed t test was used for group comparisons. A p value of <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Results

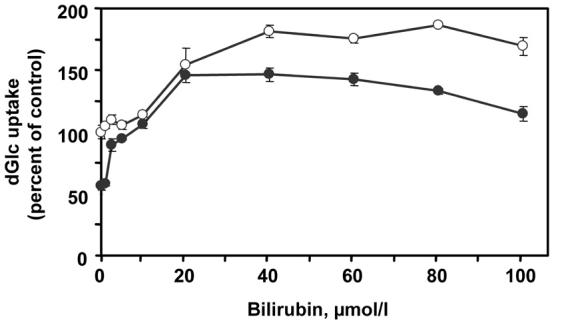

Figure 1 shows a dose-response analysis of BR-induced stimulation of glucose transport in VEC. Confluent cultures were incubated for 48 h with DMEM supplemented with 5.5 or 23 mmol/l glucose, with or without BR at the indicated concentration. As expected [12, 13], exposure of cells to 23 mmol/l glucose downregulated the rate of glucose transport (compare 32.6 ± 2.0 to 57.5 ± 1.6 pmol dGlc/106 cells/min in cells exposed to 5.5 mmol/l glucose). The incubation period lasted for 48 h because this downregulation process is normally slow in VEC and is completed within 36-48 h [12]. BR augmented the rate of glucose transport in VEC cultures exposed to both glucose concentrations, but the kinetics, dose-dependency and efficacy were different. In cells exposed to 5.5 mmol/l glucose, BR had no significant effect on the rate of glucose transport up to 10 μmol/l. Half-maximal and maximal stimulatory effects (1.45- and 1.88-fold increase, respectively) of BR in these cultures were observed at 20 and >40 μmol/l, respectively. At concentrations higher than 100 μmol/l, BR reduced endothelial cell viability in a dose-dependent manner. The effect of low concentrations of BR in VEC exposed to 23 mmol/l glucose was strikingly different than that at 5.5 mmol/l glucose: at concentrations as low as 2.5-5.0 μmol/l BR completely prevented high glucose-induced downregulation of glucose transport. It also augmented the rate of glucose transport at higher concentrations: half-maximal and maximal stimulatory effects (1.78- and 2.64-fold increase, respectively) were observed at 12 and >20 μmol/l BR, respectively. Despite the higher relative increase in the rate of glucose transport in VEC incubated at 23 mmol/l glucose in comparison with 5.5 mmol/l, the maximal rate of transport under the former condition was lower than that observed under the latter.

Figure 1. Dose-response of BR-dependent stimulation of hexose transport in VEC.

Cultures were incubated for 48 h with complete DMEM supplemented with 5.5 (open circles) or 23 mmol/l D-glucose (close circles), in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of BR. The [3H]dGlc uptake assay was performed at the end of the incubation period. The 100% value was assigned to the rate of uptake of VEC incubated with 5.5 mmol/l glucose in the absence of BR (57.5±1.6 pmol dGlc/106 cells/min). Mean ± SEM (n = 3-9).

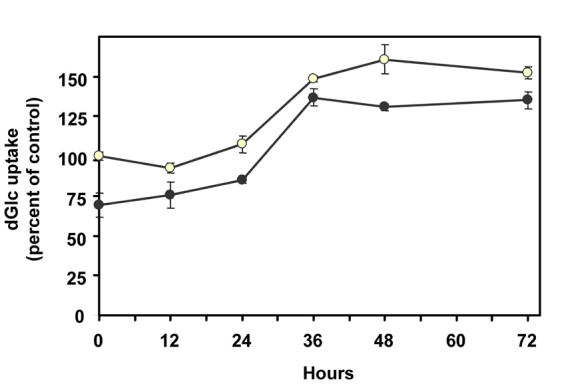

Time-course analysis of the glucose transport augmenting effect of BR is depicted in Figure 2. VEC received fresh DMEM with 5.5 or 23 mmol/l glucose, with or without 40 μmol/l BR. At this concentration, BR produced maximal effects under both glucose levels (Figure 1). A 12-24 h lag period was observed, during which BR did not alter or just marginally increased the glucose uptake capacity of cells. After this lag period, BR increased the rate of glucose uptake in a time-dependent manner, reaching a maximal effect (2.08-fold increase) within 12 h in VEC exposed to 23 mmol/l glucose. The stimulatory effect of BR in VEC maintained at 5.5 mmol/l glucose (1.64-fold increase) developed more slowly, and reached a maximum 24 h after the initial lag period.

Figure 2. Time-course of BR-dependent stimulation of hexose transport in VEC.

Cultures were incubated with complete DMEM supplemented with 5.5 (open circles) or 23 mmol/l D-glucose (close circles). Bilirubin (40 µmol/l) was added at zero time. [3H]dGlc uptake assay was performed at the indicated times. The 100% value was assigned to the rate of uptake of VEC incubated with 5.5 mmol/l glucose in the absence of BR (49.2 ± 2.7 pmol dGlc/106 cells/min). Mean ± SEM (n = 3-9).

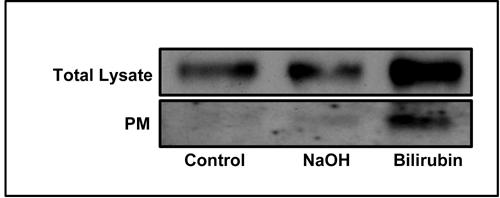

Figure 3 shows the effect of 40 μmol/l BR on GLUT-1 content and plasma membrane abundance in VEC exposed to 23 mmol/l glucose for 48 h. We chose this glucose concentration because it allows for a maximal fold-stimulation of the glucose transport system (Figures 1 and 2). The Western blot analysis of GLUT-1 in total cell lysates shows a marked increase in cells exposed to BR in comparison with control cells (either in normal DMEM or in DMEM supplemented with the NaOH vehicle). The same cultures were used for cell-surface biotinylation and separation of membrane-localized proteins, followed by Western blot analysis of GLUT-1 to assess its relative content in the plasma membrane. The corresponding blot shows a significant increase in GLUT-1 abundance in the plasma membrane of BR-treated cells in comparison with control cells.

Figure 3. Effect of BR on total and plasma-membrane localized GLUT-1.

VEC were treated with 23 mmol/l glucose and 40 µmol/l BR. The preparation of total cell lysate and the isolation cell-surface biotinylated proteins were performed as described under the 'materials and methods' section. Representative Western blots of GLUT-1 are presented.

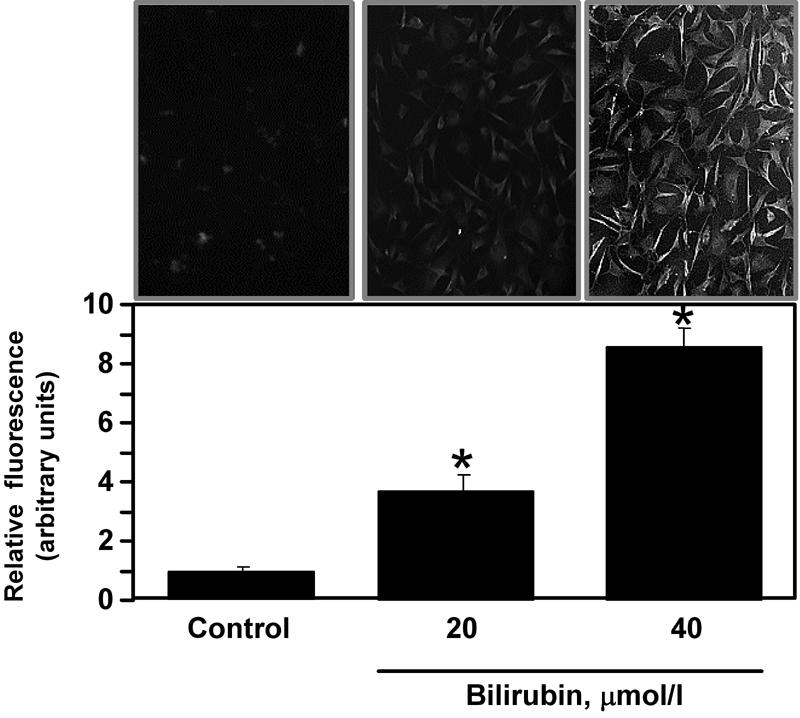

These stimulatory effects of BR on glucose transport may result from its pro-oxidant properties. To test this hypothesis we incubated (for 4 h) VEC, which were pre-loaded with the reactive oxygen species detection dye carboxy-H2DCFDA, in DMEM supplemented with 23 mmol/l glucose with or without 20 or 40 μmol/l BR, and determined the intracellular accumulation of the fluorescent carboxy-dichloro-fluoresceine product. Figure 4 shows fluorescence microscope images of VEC cultures and a summary of 3 determinations. It shows a minimal presence of reactive oxygen species in control cells, and a 3.7 ± 0.5- and 8.6 ± 0.6-fold increase in BR-mediated oxidation of H2DCFDA at 20- and 40 μmol/l, respectively.

Figure 4. BR-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species in VEC.

Cells grown on fibronectin-coated glass cover-slips were loaded with 20 µmol/l carboxy-H2DCFD and treated with BR at the indicated concentration, as described under ‘Materials and Methods’. Following fixation, the cells were taken for fluorescent microscopic determination. Upper panel shows representative images of control and BR-treated cells. Lower panel depicts the summary of 20 field measurements in 3 different slides of cells treated similarly. The fluorescence of control cells was taken as 1 unit. Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05. * in comparison with control cells.

Discussion

This study shows for the first time that unconjugated bilirubin stimulates the glucose system in VEC in a dose- and time-dependent manner, and that it blocks high glucose-induced downregulation of this system. Physiological levels of BR (<20 μmol/l) had no marked effects on the rate of glucose transport in VEC exposed to normal glucose levels. Yet, higher levels of BR increased the rate of glucose transport 1.6-1.9-fold (Figures 1 and 2). Incubation of VEC at 23 mmol/l glucose activates in these cells the natural protective mechanism that downregulates the rate of glucose transport, by destabilizing GLUT-1 mRNA and reducing GLUT-1 protein and its plasma membrane abundance [12, 13, 20]. This mechanism limits the influx of glucose to VEC in the face of hyperglycemia. The present results confirm that a 48 h incubation period of bovine aortic endothelial cells cultures at 23 mmol/l glucose significantly reduced the rate of hexose transport in comparison with cells maintained at a normal glucose level. Remarkably, physiological concentrations of BR rendered VEC insensitive to this high glucose-dependent downregulation, and the rate of glucose uptake in these cells remained high and similar to that measured in VEC at 5.5 mmol/l glucose (Figure 1). Therefore, normal plasma levels of BR blocked the natural mechanism that protects VEC against effects of hyperglycemia. Exposure of VEC to 23 mmol/l glucose and to higher BR concentrations (>20 μmol/l) also resulted in a pronounced stimulation (2.1-2.6-fold increase) of the glucose transport system. It should be noted that although the relative increase in the rate of glucose transport in VEC incubated at 23 mmol/l glucose was higher than that at 5.5 mmol/l, the maximal rate of transport under the high glucose condition was lower than that observed under normoglycemic-like conditions.

We have shown before that the induction of metabolic stress in cells using pro-oxidants (i.e., 4-hydroxy tempol) or mitochondrial uncouplers (rottlerin) activates a compensatory stress reaction to increase the expression of GLUT-1 and, subsequently, the rate of glucose transport and glycolytic production of ATP [14, 15]. The present study also shows a similar increase in GLUT-1 expression in VEC exposed to 23 mmol/l glucose and 40 μmol/l BR (Figure 3). These findings suggested that BR might also induce an oxidative stress in VEC and subsequently activate the compensatory mechanism that increases GLUT-1 expression. Indeed, using the reactive oxygen species detection dye carboxy-H2DCFDA, we were able to demonstrate a significant production of reactive oxygen species in VEC exposed to 40 μmol/l BR. These results may explain the marked increase in GLUT-1 content and its plasma membrane abundance in cells exposed to 40 μmol/l BR. Moreover, these findings also associate pathophysiological levels of BR to oxidative damage in VEC, since oxidative stress is a major detrimental factor that contributes to impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation of blood vessels, activation of the polyol pathway, activation of PKC isoforms, impaired nitric oxide function, and induction of atherosclerosis [14, 21-28].

The lack of high glucose-induced downregulation of glucose transport at normal circulating levels of BR (Figure 1) is surprising. It is unlikely that this effect results from BR-induced oxidative stress: first, similar low levels of BR had no effect on the glucose transport system in VEC maintained at 5.5 mmol/l glucose. Second, BR-dependent generation of free radicals is low in VEC exposed to normal circulating levels of BR. It has been shown that hyperglycemia per se is cytotoxic to VEC [29] by attenuating fundamental cellular functions due to generation of glucose-derived reactive oxygen species coupled to protein glycation [21-23, 28, 30-32]. In fact, high glucose-induced damage in VEC has recently been shown to be directly linked to the generation of superoxide anion [33, 34]. It has also been suggested that heme oxygenase (OH-1) participates in defense processes against glucose-induced oxidative injury by increasing the generation of BR [35]. Therefore, it is likely that BR at physiological levels acts as an antioxidant in VEC and blocks high glucose-generated free radicals or oxidative metabolites that activate the downregulatory response in these cells. Interestingly, a protective role for BR in diabetes-induced damage in endothelial cells, likely via a decrease in oxidative stress, has recently been proposed [36, 37]. Since normal glucose levels do not promote an excessive generation of free radicals in VEC, the antioxidative potential of low concentrations of BR in VEC exposed to 5.5 mol/l glucose is inconsequential.

In summary, BR augments the rate of glucose transport in primary cultures of bovine aortic endothelial cells in a dose- and time dependent manner. Under normoglycemic-like conditions, this effect was apparent only at pathological BR levels. Yet, normal BR concentrations blocked the natural protective mechanism in cultures exposed to high glucose levels. We attribute the former effect to the pro-oxidative potential of high levels of BR. Yet the latter effect could be related to an anti-oxidative capacity of low concentrations of BR. Therefore, the glucose-transport augmenting activity of BR at both normal and hyperglycemic-like conditions could be detrimental to the endothelial cell monolayer in blood vessels.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. A. Maklakov and M. Kohan for their useful advice. S. Sasson and J. Kapitulnik are members of the David R. Bloom Center for Pharmacy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. G. Cohen received a fellowship from the Hebrew University Center for Diabetes Research. This work was supported by grants from the Yedidut Foundation (Mexico) and the David R. Bloom Center for Pharmacy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

References

- 1.Fiereck EA. In: Tietz NE. Fundamentals of clinical chemistry. WB Saunders Co; 1982. Table of normal values; p. 1208. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapitulnik J. Bilirubin: an endogenous product of heme degradation with both cytotoxic and cytoprotective properties. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:773–779. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grojean S, Koziel V, Vert P, Daval JL. Bilirubin induces apoptosis via activation of NMDA receptors in developing rat brain neurons. Exp Neurol. 2000;166:334–341. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin S, Yan C, Wei X, Paul SM, Du Y. p38 MAP kinase mediates bilirubin-induced neuronal death of cultured rat cerebellar granule neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2003;353:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva RF, Rodrigues CM, Brites D. Rat cultured neuronal and glial cells respond differently to toxicity of unconjugated bilirubin. Pediatr Res. 2002;51:535–541. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200204000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akin E, Clower B, Tibbs R, Tang J, Zhang J. Bilirubin produces apoptosis in cultured bovine brain endothelial cells. Brain Res. 2002;931:168–175. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stocker R, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Antioxidant activity of albumin-bound bilirubin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:5918–5922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, McDonagh AF, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science. 1987;235:1043–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.3029864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuzil J, Stocker R. Bilirubin attenuates radical-mediated damage to serum albumin. FEBS Lett. 1993;331:281–284. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80353-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu TW, Fung KP, Wu J, Yang CC, Weisel RD. Antioxidation of human low density lipoprotein by unconjugated and conjugated bilirubins. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51:859–862. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02395-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motterlini R, Foresti R, Intaglietta M, Winslow RM. NO-mediated activation of heme oxygenase: endogenous cytoprotection against oxidative stress to endothelium. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H107–H114. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alpert E, Gruzman A, Riahi Y, Blejter R, Aharoni P, Weisinger G, Eckel J, Kaiser N, Sasson S. Delayed autoregulation of glucose transport in vascular endothelial cells. Diabetologia. 2005;48:752–755. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1681-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alpert E, Gruzman A, Totary H, Kaiser N, Reich R, Sasson S. A natural protective mechanism against hyperglycaemia in vascular endothelial and smooth-muscle cells: role of glucose and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. Biochem J. 2002;362:413–422. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alpert E, Altman H, Totary H, Gruzman A, Barnea D, Barash V, Sasson S. 4-Hydroxy tempol-induced impairment of mitochondrial function and augmentation of glucose transport in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:1985–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alpert E, Gruzman A, Tennenbaum T, Sasson S. Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors stimulate glucose transport in L6 myotubes in a protein kinase Cdelta-dependent manner. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaiser N, Vlodavsk I, Tur-Sinai A, Fuks Z, Cerasi E. Binding, internalization, and degradation of insulin in vascular endothelial cells. Diabetes. 1982;31:1077–1083. doi: 10.2337/diacare.31.12.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alpert E, Gruzman A, Lardi-Studler B, Cohen G, Reich R, Sasson S. Cyclooxygenase-2 (PTGS2) inhibitors augment the rate of hexose transport in L6 myotubes in an insulin- and AMPKalpha-independent manner. Diabetologia. 2006;49:562–570. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasson S, Cerasi E. Substrate regulation of the glucose transport system in rat skeletal muscle. Characterization and kinetic analysis in isolated soleus muscle and skeletal muscle cells in culture. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16827–16833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kehrer JP, Paraidathathu T. The use of fluorescent probes to assess oxidative processes in isolated-perfused rat heart tissue. Free Radic Res Commun. 1992;16:217–225. doi: 10.3109/10715769209049175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Totary-Jain H, Naveh-Many T, Riahi Y, Kaiser N, Eckel J, Sasson S. Calreticulin destabilizes glucose transporter-1 mRNA in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells under high-glucose conditions. Circ Res. 2005;97:1001–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000189260.46084.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzik TJ, Mussa S, Gastaldi D, Sadowski J, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Channon KM. Mechanisms of increased vascular superoxide production in human diabetes mellitus: role of NAD(P)H oxidase and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2002;105:1656–1662. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012748.58444.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hink U, Li H, Mollnau H, Oelze M, Matheis E, Hartmann M, Skatchkov M, Thaiss F, Stahl RA, Warnholtz A et al. Mechanisms underlying endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circ Res. 2001;88:E14–E22. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.2.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunt JV, Dean RT, Wolff SP. Hydroxyl radical production and autoxidative glycosylation. Glucose autoxidation as the cause of protein damage in the experimental glycation model of diabetes mellitus and ageing. Biochem J. 1998;256:205–212. doi: 10.1042/bj2560205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii H, Koya D, King GL. Protein kinase C activation and its role in the development of vascular complications in diabetes mellitus. J Mol Med. 1998;76:21–31. doi: 10.1007/s001090050187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milstien S, Katusic Z. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin by peroxynitrite: implications for vascular endothelial function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263:681–684. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pieper GM, Gross GJ. Oxygen free radicals abolish endothelium-dependent relaxation in diabetic rat aorta. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H825–H833. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.4.H825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sano T, Umeda F, Hashimoto T, Nawata H, Utsumi H. Oxidative stress measurement by in vivo electron spin resonance spectroscopy in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 1998;41:1355–1360. doi: 10.1007/s001250051076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolff SP, Dean RT. Glucose autoxidation and protein modification. The potential role of 'autoxidative glycosylation' in diabetes. Biochem J. 1987;245:243–250. doi: 10.1042/bj2450243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Slevin M, Duraisamy Y, Gaffney J, Smith CA, Ahmed N. Comparison of protective effects of aspirin, D-penicillamine and vitamin E against high glucose-mediated toxicity in cultured endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brownlee M. Lilly Lecture 1993. Glycation and diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1994;43:836–841. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.6.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brownlee M. Negative consequences of glycation. Metabolism. 2000;49:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(00)80078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bucala R, Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation end products in diabetic renal and vascular disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:875–888. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piconi L, Quagliaro L, Assaloni R, Da Ros R, Maier A, Zuodar G, Ceriello A. Constant and intermittent high glucose enhances endothelial cell apoptosis through mitochondrial superoxide overproduction. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2006;22:198–203. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quagliaro L, Piconi L, Assaloni R, Da Ros R, Szabo C, Ceriello A. Primary role of superoxide anion generation in the cascade of events leading to endothelial dysfunction and damage in high glucose treated HUVEC. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacerdoti D, Olszanecki R, Li Volti G, Colombrita C, Scapagnini G, Abraham NG. Heme oxygenase overexpression attenuates glucose-mediated oxidative stress in quiescent cell phase: linking heme to hyperglycemia complications. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:103–111. doi: 10.2174/1567202053586802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawamura K, Ishikawa K, Wada Y, Kimura S, Matsumoto H, Kohro T, Itabe H, Kodama T, Maruyama Y. Bilirubin from heme oxygenase-1 attenuates vascular endothelial activation and dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:155–160. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000148405.18071.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodella L, Lamon BD, Rezzani R, Sangras B, Goodman AI, Falck JR, Abraham NG. Carbon monoxide and biliverdin prevent endothelial cell sloughing in rats with type I diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:2198–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]