Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the proportion of family physicians who diagnose rheumatoid arthritis (RA) correctly and to note how they report they would manage RA patients.

DESIGN

Mailed survey (self-administered questionnaire) requesting comments on vignettes.

SETTING

Province of Quebec.

PARTICIPANTS

Computer-generated random sample of family physicians registered with the Quebec College of Family Physicians.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

The proportion of family physicians who recognized RA and their reported management strategies.

RESULTS

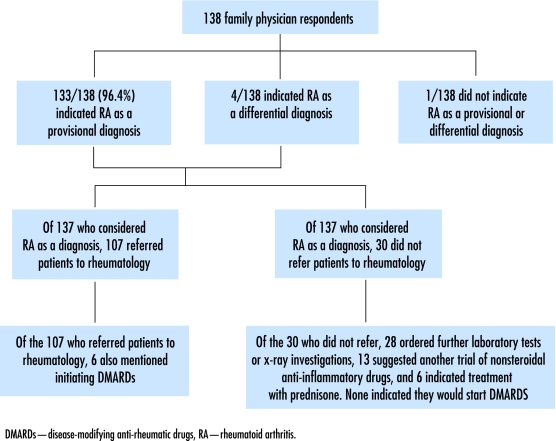

Most respondents recognized the vignette presentation as a case of RA; 133/138 (96.4%) indicated RA as their provisional diagnosis, and all but 1 of the remaining respondents listed RA as a differential diagnosis. Of those who considered RA as a provisional or possible diagnosis, 107 (77.5% of all respondents) suggested referring the patient to a rheumatologist. Among the physicians who suggested referral, none indicated they would initiate disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

CONCLUSION

Almost all respondents considered RA as a provisional or differential diagnosis. Although many suggested referring the patient to a rheumatologist, almost a quarter did not. Initiating DMARDs before referring patients to rheumatologists appears to be rare. Since DMARDs given during the early stages of RA are known to decrease damage and dysfunction, ways to increase their use and optimize care pathways for new-onset inflammatory arthritis are urgently needed.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer la proportion des médecins de famille qui diagnostiquent correctement l’arthrite rhumatoïde (AR) et décrire de quelle façon ils disent vouloir traiter les patients atteints.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête postale (questionnaire auto-administré) avec vignettes à commenter.

CONTEXTE

Province de Québec.

PARTICIPANTS

Un échantillon aléatoire généré par ordinateur de médecins de famille inscrits au Collège des médecins de famille du Québec.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES À L’ÉTUDE

Proportion des médecins de famille qui identifiaient correctement l’AR et les stratégies de traitement qu’ils disaient envisager.

RÉSULTATS

La plupart des répondants ont reconnu un cas d’AR dans les vignettes présentées; 133/138 (96,4%) ont mentionné ce diagnostic comme provisoire, et tous les autres sauf un l’ont inclus dans le diagnostic différentiel. Parmi ceux qui mentionnaient l’AR comme diagnostic provisoire ou possible, 107 (77,5% de tous les répondants) suggéraient d’adresser le patient à un rhumatologue. Toutefois, parmi ceux qui suggéraient une telle consultation, aucun n’indiquait qu’il instaurerait un traitement avec des médicaments antirhumatismaux modificateurs de la maladie (MARMM).

CONCLUSION

Presque tous les répondants considéraient l’AR comme un diagnostic provisoire ou différentiel. Même si plusieurs suggéraient de diriger le patient en rhumatologie, près du quart ne le faisaient pas. Il est apparemment rare qu’un traitement aux MARMM soit instauré avant la demande de consultation en rhumatologie. On sait que l’administration de MARMM à un stade précoce de l’AR réduit les lésions et dysfonctions; il est donc urgent de trouver des façons d’accroître leur usage et d’optimiser ainsi les stratégies de traitement de l’arthrite inflammatoire dès le début.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is now possible through early use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The best opportunity for preventing damage and disability comes during the first few months of disease.

Unfortunately, data suggest severe problems with timely access to care for patients with RA in Canada, including delayed access to DMARDs for patients with new-onset RA.

This study aimed to determine the accuracy with which primary care physicians diagnosed RA and to describe their proposed management of RA patients, particularly regarding referral to specialists.

Results showed that almost all respondents considered RA as a provisional or differential diagnosis in the case described. Although many suggested referring the patient to a rheumatologist, almost a quarter did not. Initiating DMARDs before referral appears to be rare.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

On peut maintenant intervenir auprès des patients souffrant d’arthrite rhumatoïde (AR) par l’utilisation précoce de médicaments antirhumatismaux modificateurs de la maladie (MARMM). C’est durant les premiers mois de la maladie que les chances de prévenir les lésions et invalidités sont les meilleures.

Malheureusement, les données donnent à penser, que les patients souffrant d’AR au Canada rencontrent de graves problèmes d’accès en temps opportun aux soins, notamment un retard dans l’accès aux MARMM en début de maladie.

Cette étude voulait déterminer la précision avec laquelle les médecins de soins primaires diagnostiquent l’AR et décrire quel traitement ils envisagent pour ces patients, particulièrement en ce qui concerne le recours aux consultations en spécialité.

Les résultats montrent que devant le cas qui leur était présenté, la plupart des répondants ont identifié l’AR comme un diagnostic provisoire ou différentiel. Quoique plusieurs suggéraient de diriger le patient à un rhumatologue, près d’un quart ne le faisaient pas. Il semble rare qu’on instaure un traitement aux MARMM avant la demande de consultation.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a progressive, painful, disabling disease that affects about 1% of the population. Intervention is now possible through early use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).1 The best opportunity for preventing damage and disability comes during the first few months of disease. Reports indicate better outcomes for patients who begin DMARD therapy early.2-4 Optimal care of people with RA often hinges on early referral to rheumatologists. Quality of care and health outcomes are better for RA patients who have contact with relevant specialists5 than they are for those who do not. Since Canadian family physicians function both as front-line caregivers and gatekeepers for access to specialists, they have an essential role in ensuring RA patients receive optimal care. Unfortunately, data suggest severe problems with timely access to care for RA patients in our country,6 including delayed access to DMARDs for patients with new-onset RA.7,8 Factors contributing to the problem include both family physicians’ difficulties in diagnosing RA and barriers to optimal referral practices.

Our primary research objectives were to determine the accuracy with which family physicians diagnose RA, using vignette presentations, and to describe their proposed management of RA patients, particularly regarding referral to specialists.

METHODS

The survey was mailed to a random sample of family physicians in Quebec drawn from the mailing list of the Quebec College of Family Physicians.9 This approach was based on the fact that simple random sampling strategies had been used in similar surveys where researchers were successful in producing samples whose demographic profiles reflected those of their target populations.10

From a computer-generated random sample of 600 physicians, we excluded those who were deceased (n = 6), retired (n = 53), or not actively practising family medicine for other reasons (n = 99). We were left with 442 physicians potentially eligible to participate in our study. To be included, physicians had to be in active family practice at the location noted on the College’s mailing list. We calculated that, if we had 125 to 150 respondents, our study would be powered to provide a point estimate of the percentage of physicians referring suspected RA patients to rheumatologists, with an appropriately narrow 95% confidence interval (within 15 percentage points), an alpha level of .05, and a beta level of .20

Our survey was based on the methods used by Glazier et al7,8 to assess family physicians’ management of arthritis. Content was developed with input from family medicine, rheumatology, physiotherapy, and community health. Two unlabeled vignettes were presented: one showed a classic early RA presentation of subacute polyarticular swelling and stiffness for 2 months in a young woman, and the other showed uncomplicated mild osteoarthritis in an elderly man with chronic knee pain. For each vignette, physicians were asked to provide provisional diagnoses and differential diagnoses. Physicians were then asked to indicate their management strategy for each case. This could be done by filling in proposed actions on blank lines and by checking off options that included the following: a trial of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), laboratory investigations, radiologic examinations, treatment with prednisone, referral to a rheumatologist, and referral to physiotherapy or occupational therapy.

We used an adapted version of the Dillman method.11 It included 2 follow-up mailings and follow-up calls to nonrespondents. During statistical analysis, we determined summary statistics for respondents’ demographic characteristics and compared them with characteristics found in the College of Family Physicians of Canada’s National Family Physician Survey—Regional Report (Québec).12 We calculated the percentages of respondents who recognized RA in the vignette and who chose various items for managing patients, including referral to a specialist. The study protocol was approved by McGill University’s Research Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

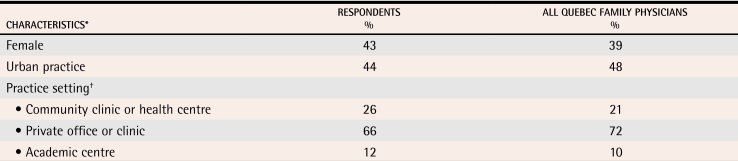

Of 442 eligible physicians, 138 completed and returned the questionnaire for a response rate of 31.2%, which reaches or surpasses response rates of similar surveys.13-17 Eighty-one (18.3%) of the 442 physicians refused to complete the survey, and the remainder did not respond at all despite repeated mailings and follow-up calls (Figure 1). The demographic and practice characteristics of respondents were similar to the characteristics of the entire population of Quebec family physicians (Table 112). The demographic characteristics and practice locations of respondents were similar to those of nonrespondents.

Figure 1.

Flowchart summarizing results of the survey on diagnosis of RA using a vignette case and self-reported management practices

Table 1. Characteristics of survey respondents compared with all Quebec family physicians.

Mean age of respondents was 47.6 years (± 9.5 years); mean age of all Quebec family physicians was 43.9 years (± 8.7 years).

Data from the College of Family Physicians of Canada.12

*For all characteristics, 95% confidence intervals for estimates overlap, indicating no evidence of important differences between survey respondents and all Quebec family physicians.

†The combined percentage exceeds 100%, as some respondents indicated more than one category.

The vast majority of respondents recognized the first vignette case as RA; 133/138 (96.4%) indicated RA as their provisional diagnosis, and all but 1 of the remaining respondents listed RA as a differential diagnosis. Of those who considered RA as a provisional diagnosis, 107 (80.5%) suggested referral to a rheumatologist (95% confidence interval 70.2 to 84.1). Of the 30 respondents who did not suggest referring the first vignette case to a rheumatologist, 28 indicated that they would order further laboratory tests and radiographs, 15 suggested another trial of NSAIDs, 6 indicated treatment with prednisone, and 1 suggested referral to a physiotherapist. Among the physicians who did not refer patients to rheumatology, none indicated they would start DMARDs; only 6 respondents among the entire sample mentioned the need for DMARDs.

DISCUSSION

Results of our research update our understanding of how family physicians likely deal with patients presenting with symptoms of new-onset inflammatory arthritis. Most studies of this disease were done a decade ago.7,8 Given the recent ground-breaking developments in RA treatment1 and the fact that these treatments seem to work best if administered early in the course of disease, a re-assessment of the situation, evaluating diagnostic accuracy and referral behaviour, is long overdue.

Most respondents in our sample diagnosed the probable RA case appropriately. Though many suggested referral to a rheumatologist, almost a quarter did not. Initiating DMARDs before referral to rheumatology appears to be rare. Lacaille et al6 studied referral rates and use of DMARDs in British Columbia and had similar findings, noting that most DMARDs were initiated by rheumatologists rather than by family physicians. In comparing self-reported rheumatology referral rates to administrative data reports, we suspected that actual referrals for new-onset RA were fewer than reported by our respondents.18 Previous authors have indicated that, although self-reports can provide useful information, they should be interpreted with caution, keeping in mind that self-reporting sometimes exaggerates true behaviour.19

These findings cause great concern, since delay in DMARD treatment is associated with severe damage and dysfunction.2 In an optimal care pathway for new-onset RA, early referral and DMARD treatment are key.4 Our results suggest that thousands of people with RA are being denied prompt treatment that could prevent disability. Recently, the arthritis community has tried to encourage early referral of patients with inflammatory arthritis, even if they do not have a definitive diagnosis. This has been acknowledged in “standards of care” put forth by the Alliance for a Canadian Arthritis Program at the national Summit for Arthritis Care and Prevention held in Ottawa in November 2005. At this summit, the standard of care relevant to inflammatory arthritis recommended that, once recognized, inflammatory arthritis should be considered an urgent condition requiring prompt appropriate treatment (including specialty referral).

Once they recognize a case of suspected RA, family physicians in large part determine the course of patients’ care from that point forward. Because family physicians often do not see many patients with RA, they might not be aware of recent changes in optimal management and they might lack the experience to judge which DMARD should be prescribed for a particular patient. Our results suggest that many family physicians would order more tests, which could delay referral, even when a provisional diagnosis of RA has been made. In general, it might be appropriate to order tests to confirm a diagnosis or assign priority. Previous authors have raised concern over delays in definitive therapy (early DMARD treatment) that could arise when investigations are favoured over early referral.

The current system for referral to rheumatologists is a barrier to prompt initiation of DMARDs; waiting lists for rheumatologists in Quebec (and across Canada) are long, meaning that once patients are referred, further delays occur unless rheumatologists are alerted that the referral is for RA or suspected RA. To improve patient care, we believe patients with RA should be flagged by referring physicians, and these referring physicians should be aware that patients will be assessed promptly if rheumatologists are notified. Otherwise patients will continue to suffer unnecessarily.

In order to explore barriers to care and solutions, as the next phase of our research, we are working to identify the barriers that prevent timely access to appropriate care. We are conducting focus groups with patients, family physicians, specialists, and policy makers from across the province. Working with decision makers, our findings could then be used to inform current thinking on how to restructure delivery of care for chronic diseases, such as RA.

Limitations

Although we believe our survey respondents were representative of the family physician population in Quebec, our sample might have been biased toward respondents interested in musculoskeletal diseases. It could be argued that the results thus represent the “best-case scenario” in terms of current practice. Diagnostic accuracy in the entire family physician population (particularly among the subpopulation represented by the nonrespondents) might be more variable. As well, the actual practices of physicians might not be reflected in their self-reported behaviour. In fact, as mentioned earlier, administrative data suggest that rates of rheumatology referrals for new-onset RA (as identified by physician billing codes from outpatient encounters) could be lower than self-reported rates.18 Our results, however, give us an opportunity to examine the “best-practice” care pathways provided to patients with RA by family physicians today.

Conclusion

Many of our respondents appropriately considered RA as the diagnosis in a case vignette. Though most suggested referring the patient to a rheumatologist, almost a quarter did not. Initiating DMARDs before referral to rheumatology is very rare. This suggests that thousands of people with RA are being denied prompt treatment; the cost in terms of subsequent disability is huge. Because DMARD treatment is known to prevent damage and dysfunction, our findings signal an urgent need for optimizing care pathways in early RA.

Biographies

Dr Bernatsky is a faculty member in the Department of Medicine, Division of Clinical Epidemiology at the McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, Quebec.

Dr Shrier is a faculty member in the Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Community Studies at the SMBD–Jewish General Hospital in Montreal.

Dr Feldman is a faculty member in the Faculty of Medicine in the École de réadaptation at the University of Montreal; Ms Toupin was Dr Feldman’s graduate student.

Dr Haggerty is a faculty member in the Département de Sciences de la santé communautaire at Sherbrooke University in Quebec.

Dr Tousignant is a faculty member in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at McGill University in Montreal.

Dr Zummer practises in the Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont at the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Pincus T, Sokka T. How can the risk of long-term consequences of rheumatoid arthritis be reduced? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15(1):139–170. doi: 10.1053/berh.2000.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lard LR, Visser H, Speyer I, vander Horst-Bruinsma IE, Zwinderman AH, Breedveld FC, et al. Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. Am J Med. 2001;111(6):446–451. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00872-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potter T, Mulherin D, Pugh M. Early intervention with disease-modifying therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: where do the delays occur? Rheumatology. 2002;41:953–955. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.8.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Kalden JR, Schiff MH, Smolen JS. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: evidence based development of a clinical guide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:290–297. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.4.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yelin EH, Such CL, Criswell LA, Epstein WV. Outcomes for persons with rheumatoid arthritis with a rheumatologist versus a non-rheumatologist as the main physician for this condition. Med Care. 1998;36(4):513–522. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199804000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacaille D, Anis AH, Guh DP, Esdaile JM. Gaps in care for rheumatoid arthritis: a population study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(2):241–248. doi: 10.1002/art.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glazier RH, Dalby DM, Badley EM, Hawker GA, Bell MJ, Buchbinder R, et al. Management of the early and late presentations of rheumatoid arthritis: a survey of Ontario primary care physicians. CMAJ. 1996;155:679–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glazier RH, Dalby DM, Badley EM, Hawker GA, Bell MJ, Buchbinder R, et al. Management of common musculoskeletal problems: a survey of Ontario primary care physicians. CMAJ. 1998;158:1037–1040. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collège des médecins du Québec. L’Annuaire médical Québec 2003-2004. Québec, QC: Collège des médecins du Québec; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makni H, O’Loughlin J, Tremblay M, Gervais A, Lacroix C, Dery V, et al. Smoking prevention counseling practices of Montreal general practitioners. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(12):1263–1267. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.12.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet surveys: the tailored design method. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.College of Family Physicians of Canada. National Family Physician Survey—Regional Report (Québec). Mississauga, Ont: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foley KA, Denke MA, Kamal-Bahl S, Simpson RJ, Berra K, Sajjan S, et al. The impact of physician attitudes and beliefs on treatment decisions: lipid therapy in high-risk patients. Med Care. 2006;44(5):421–428. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000208017.18278.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowan AE, Winston CA, Davis MM, Wortley PM, Clark SJ. Influenza vaccination status and influenza-related perspectives and practices among US physicians. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34(4):164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scatarige JC, Weiss CR, Diette GB, Haponik EF, Merriman B, Fishman EK. Scanning systems and protocols used during imaging for acute pulmonary embolism: how much do our clinical colleagues know? Acad Radiol. 2006;13(6):678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ku JH, Kim SW, Paick JS. Questionnaire survey of urologists’ initial treatment practices for acute urinary retention secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia in Korea. Urol Int. 2006;76(4):314–320. doi: 10.1159/000092054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Rourke M, Richardson LD, Wilets I, D’Onofrio G. Alcohol-related problems: emergency physicians’ current practice and attitudes. J Emerg Med. 2006;30(3):263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman D, Bernatsky S, Haggerty J, Tousignant P, Leffondré K, Roy Y, et al. Referral to rheumatology in persons with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA): a population based study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9 Suppl):1030. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Lomas J, Ross-Degnan D. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999;11(3):187–192. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/11.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]