Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the experiences with cancer of adults diagnosed when between 20 and 35 years old.

DESIGN

Qualitative study using semistructured interviews.

SETTING

Largest health care region in the province of New Brunswick.

PARTICIPANTS

Six men and 9 women cancer patients and survivors.

METHOD

Fifteen adults interviewed when between the ages of 20 and 43 representing a variety of cancers and stages of disease were recruited for this study. Interviews were guided by a set of open-ended questions and explored participants’ experiences with cancer from initial presentation of symptoms through to survivorship issues.

MAIN FINDINGS

The most important clinical issue that emerged from the analysis was that participants’ youth appeared to contribute to delays in diagnosis of cancer. These delays were attributed to either patients’ or physicians’ inaction. Some patients attributed their initial cancer symptoms to the adverse effects of alcohol or excessive partying; others feared a bad diagnosis and delayed seeking help. Family physicians frequently interpreted nonspecific symptoms as resulting from patients’ lifestyle choices and were reluctant to consider a diagnosis of cancer. Several family physicians reportedly believed that persistent symptoms could not be the result of cancer because patients were too young.

CONCLUSION

Although cancer is relatively rare in young adults, family physicians need to include it in differential diagnoses. Both patients and physicians tend to minimize cancer symptoms in young adults. Delays in diagnosis might not affect health outcomes, but can cause distress to young adults with cancer.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer comment les adultes de 20 à 35 ans vivent le fait d’être confrontés à un diagnostic de cancer.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Étude qualitative à l’aide d’entrevues semi-structurées.

CONTEXTE

La région sanitaire la plus étendue du Nouveau-Brunswick.

PARTICIPANTS

Six hommes et 9 femmes atteints ou survivants d’un cancer.

MÉTHODE

Pour cette étude, 15 adultes représentant divers types de cancer à divers stades ont été interviewés alors qu’ils avaient entre 20 et 43 ans. Les entrevues étaient conduites à l’aide d’un ensemble de questions ouvertes; elles exploraient l’expérience vécue par les participants à partir des premiers symptômes jusqu’à la période de survie.

PRINCIPALES OBSERVATIONS

L’issue la plus importante révélée par l’analyse est que l’âge des participants semble contribuer à retarder le diagnostic du cancer. Ce retard pouvait être attribué à l’inaction du patient ou du médecin. Certains patients attribuaient les symptômes initiaux du cancer à trop d’alcool ou de sorties; d’autres la croyaient consultation, craignant le verdict. Les médecins de famille interprétaient souvent des symptômes non spécifiques comme résultant du mode de vie choisi par le patient, hésitant à envisager un diagnostic de cancer. Apparemment, plusieurs médecins croyaient que les symptômes persistants ne pouvaient être dus à un cancer, parce que le patient était trop jeune.

CONCLUSION

Même si le cancer est relativement rare chez le jeune adulte, le médecin de famille doit l’inclure dans le diagnostic différentiel. Autant le patient que le médecin ont tendance à minimiser les symptômes de cancer chez le jeune adulte. Même si un retard de diagnostic ne modifie pas nécessairement les conséquences pour la santé, il peut être source de détresse chez le jeune adulte qui a un cancer.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

This qualitative study explored the experiences of young adults diagnosed with cancer. Delays in diagnosis were reported by about 75% of participants.

Patients often delayed seeking a diagnosis because of a feeling of invincibility or a state of denial. Physicians sometimes failed to consider a diagnosis of cancer because patients were so young.

Family physicians should remember that youth is not always a protective factor against cancer.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Cette étude qualitative voulait savoir comment les jeunes adultes confrontés à un diagnostic de cancer vivent cette expérience. Des retards de diagnostic ont été mentionnés par environ 75 % des participants.

Les patients tardent souvent à consulter en raison d’un sentiment d’invulnérabilité ou parce qu’ils nient le problème. Parfois, le médecin n’envisage pas le diagnostic de cancer parce que le patient est trop jeune.

Le médecin de famille devrait se souvenir que l’âge ne procure pas toujours une protection contre le cancer.

During the past decade, 100 000 adults between the ages of 20 and 44 were diagnosed with cancer in Canada. One quarter died of cancer, and 850 000 potential years of life were lost.1 Researchers estimated that, in 2005, more than 6000 adults between the ages of 20 and 39 years would develop cancer.2

Although the total number of young adults who develop cancer is small, and overall incidence is stable for most cancers, rates of thyroid cancer among young women and testicular cancer among young men are rising.3 The most common cancers among young adults are breast and testicular cancer.3 Young women are twice as likely to develop cancer as young men are. In general, the prognosis of young adults with cancer is good, yet cancer remains the leading cause of death among young women and the third leading cause of death (after accidental death and suicide) among young men.1

Patients with specific and nonspecific symptoms of cancer present most often to family physicians. Regular visits to a physician can be an important cancer prevention strategy and offer opportunities for early detection of cancer.4 Family physicians, however, do not always know when to screen or order appropriate tests or have the confidence to diagnose cancer or ask patients the important questions.5-9 These factors can contribute to delays in diagnosing cancer. Patients’ inaction—often rooted in fear—and sometimes the health care system can also cause delays in diagnosis.10-12 Some believe that the sooner a malignant growth is treated, the better the outcome,12-16 but others argue that delayed diagnosis has little effect on outcome.17,18 Regardless of clinical outcome, delayed diagnosis could cause substantial problems for both patients and physicians. It heightens patients’ stress and anxiety; it might limit treatment options; it can harm patient-physician relationships; and it can expose physicians to malpractice suits.19-22

An extensive search of the literature revealed several studies dealing with cancer issues among older adults and among children. Few studies looked at the experiences of young adults with cancer, and even fewer focused specifically on (delayed) diagnosis. Although cancer rates among young adults are double those among children, there is much more literature on pediatric cancer. Young adults’ cancer issues seem to fall through the crack between children’s cancer issues and older adults’ issues.23,24 This study was designed to fill that gap and to study the cancer experiences of adults diagnosed when between 15 and 35 years old.

METHOD

Setting

New Brunswick is largely a rural province with a population of 760 000 people. The 7 health care regions in the province provide a variety of health care services. This study took place in the largest health care region in the province.

Participant recruitment and data collection

Participants were recruited through newspaper advertisements, radio announcements, and posters in doctors’ offices and local gymnasiums. Over several weeks, 15 people volunteered to participate in the study. Before the interviews commenced, written informed consent and demographic information were obtained from participants. Open-ended questions were used in the interviews, which were conducted wherever participants suggested. There were 5 general questions starting with, “Could you please tell me about when you were diagnosed with cancer and how you felt about that?” Mr Hamilton interviewed the men, and Ms Easley and Dr Miedema interviewed the women.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were read and analyzed by 4 researchers, including the interviewers, immediately after each interview. Responses were coded and compared with previous interviews. New codes were documented during numerous team meetings. After 13 interviews, no new codes were identified. The 2 remaining interviews were completed, and their data were added to the analysis. The team identified 3 central themes: delayed diagnosis, support issues, and coping strategies. This paper focuses exclusively on a single theme: delayed diagnosis.

To present a rigorous qualitative analysis, the study methods were evaluated for how well they could be audited and for their credibility.25 For auditing purposes, we documented all steps from transcription of raw data to final analysis (eg, notes, transcripts, coding schemes, team meeting minutes). Credibility was achieved by inviting participants to comment on the study summary. We were able to reach 12 of the 15 participants; one had died shortly after the interview, and 2 others could not be located. Only 1 participant chose to comment, stating that the summary reflected his or her experiences. Finally, we believe we have faithfully shown participants’ everyday reality because 3 members of the research team were young adults themselves, and 1 was a young adult cancer survivor.25

The study was approved by the regional hospital’s Research Ethics Committee.

FINDINGS

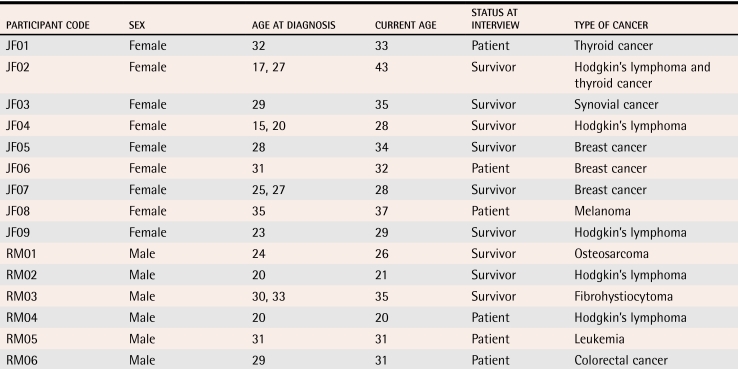

Participants were a diverse sample ranging from first-year university students to older people with established careers and families. The types of cancers represented in the group ranged from breast cancer to an uncommon abdominal synovial cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

Despite the fact that the interviewers did not focus exclusively on the issue of diagnosis, it became apparent that the process of diagnosis was an important aspect of the overall cancer experience. Some reported that they were diagnosed promptly and received timely treatment. A man aged 21 with Hodgkin’s lymphoma described his experience as follows:

After [seeing a family physician], it went fairly quickly, like I saw the specialist and then maybe 2 or 3 weeks later I had the surgery and right after that—maybe the next month—I just went to the next doctor and just kept going. I was in [city X] getting the treatments [radiation] within 21⁄2 months. I guess it was in September or August that I went to see the throat specialist, and in November I started doing the radiation, so it went by pretty quickly.

More than three quarters of participants, however, described some delay in the diagnostic process. These delays were reportedly caused by either patients’ or physicians’ inaction.

Patients’ inaction

Many participants used the word invincible to describe how they saw themselves before the cancer diagnosis. They assumed that such symptoms as fatigue and visual disturbances were the result of lifestyle choices, such as too much partying, too much alcohol consumption, and other “bad habits”. Others ignored symptoms out of fear of serious illness. A 28-year-old female breast cancer patient said:

Well, my boyfriend (who is my husband now) said, “You know you have a lump there, don’t you?” And I said, “No.” And he said, “Well, you do.” So, I felt it and I had a little lump around my nipple and I thought, well that is nothing, you always hear about people with these lumps.

In this case, the young woman’s delay in seeking medical attention was partly because she had dismissed her symptoms but also because of the shortage of family physicians in her area. She could not find a family physician in the city to which she had just moved and had to wait for an opportunity to visit her physician in her previous home town. Visiting the physician was further complicated by a lack of transportation.

When symptoms persisted, some participants developed a sense of foreboding, fearing a diagnosis of cancer. This fear contributed to delay in seeking medical attention. One man aged 20 with Hodgkin’s lymphoma explained:

I mean, I guess it’s partly my fault that I didn’t go to the [family] doctor, but I thought it was just a cold. And I was kind of afraid of going to the doctors and finding out what it was.… Even when I started thinking that it might be [cancer], I kind of waited a little longer than I should have.

A few participants whose cancer recurred indicated that they actively denied persistent symptoms, even though “deep down” they knew what was happening, having gone through it before. A 28-year-old woman with Hodgkin’s lymphoma who was first diagnosed with cancer during her teenage years said:

I wasn’t feeling well, but I wouldn’t admit it. I was in [city X], away from my family. I came home on the weekends, but I knew that there was something wrong… anyway, so it was at Christmas time that I came home for the holidays and I got sick. I had a cold that just wouldn’t go away. So, I never, never said, you know it could be back [cancer recurrence], but it was in the back of my mind.

Physicians’ inaction

Some delays were due to physicians’ reluctance to make a diagnosis. One 29-year-old participant, who had a very unusual synovial cancer, had a difficult time obtaining the proper diagnosis from either her family physician or a specialist.

I guess we went for months dealing with the allergies first, and when that was done, I was back and said okay, there is a little lump there now, and it was about the size of a pea maybe, and [the family physician] still said it was nothing, you know, it was just a lipoma and tried to convince me of that. But I kept going back because I just… it was, you know, it was bothering me. So, [the family physician] said we will send you to the surgeon. I went to the surgeon. The surgeon gave me the same diagnosis, it was a lipoma, didn’t need to come out, it was just a fat cluster, you know, it might grow a bit, don’t be concerned.…

A 25-year-old woman with breast cancer had a similar experience. She reported, “So I went for an ultrasound and they looked at it, and you could see it [lump in breast], and they said it is probably nothing because you are so young.”

Some participants described cancer-specific symptoms, but their physicians thought that, given their youth, cancer was unlikely. One 29-year-old man, who died of colorectal cancer shortly after his interview, waited almost a full year for a final diagnosis and described encounters with his family physician.

[The family physician] started putting me on stool softeners in September; [that] was the same thing I tried to do to myself. For some reason I thought that [the family physician] knew something more.… I went to see [the family physician] a couple of times but [the family physician] just put me on more frigging stool softeners.… I was losing a little bit of weight,… but [the family physician] still didn’t seem to make a difference... I think it was February, and I had lost like 55 lbs and I just walked in and said, “there’s something wrong.” [The family physician] said, “Well, if you were 65, I would say it was cancer, but it can’t be.”

Another participant, aged 32 with breast cancer, described her initial consultation with her family physician after she found a large lump in her breast, “So I went in and saw the doctor, [the family physician] sort of was really hum and hum saying, ‘Oh you know, it’s probably just a cyst because you’re so young.’ And I’m like, ‘No, find out what it is.’”

Not only family physicians, but other medical professionals assumed that age was a protective factor also. One 35-year-old man with fibrohistiocytoma described his experience: “I had my MRI, and they made comments and asked me if I hurt myself cause I guess I was young and usually they don’t get young people with cancer in their legs.”

DISCUSSION

There is very little literature on young adults’ experiences with cancer, so the goal of this study was to gain an understanding of these experiences. We did not set out to focus on a specific topic, but analysis of the data showed that many participants perceived their diagnosis to have been delayed. Sometimes participants themselves postponed seeking medical attention after they had specific or nonspecific symptoms. It is not uncommon for patients in denial to minimize their complaints, which could lead to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.26 In a substantial number of cases, however, physicians ignored symptoms because patients’ age did not fit a cancer profile. Physician-caused delay in cancer diagnosis has been reported in the literature for both adolescents and older adults.27-29

With the exception of 1 study participant, it is unclear whether these delays in diagnosis resulted in worse outcomes for patients. In the literature, there appears to be a lack of consensus on the effects of delayed diagnosis. Size of tumours at time of presentation seems to have as much effect on outcome as diagnostic delays.15,29,30 Even if a diagnostic delay does not seriously affect the outcome of the disease, it can limit treatment options for certain cancers and might leave physicians open to malpractice suits.31 In the United States, most clinical cancer malpractice suits are in relation to perceived delays in breast cancer diagnosis. When patients think physicians are to blame for delayed diagnoses, patient-physician relationships can be severely compromised.21,22 Finally, a perceived delay in cancer diagnosis adds considerable stress to an already stressful situation.20,32 High stress levels might hinder treatment.33

There is evidence in the literature of delayed cancer diagnosis in children because physicians do not suspect serious illness; our study found a similar tendency. A contributing factor is young adults’ tendency not to suspect serious disease either, along with their sense of invincibility.

Although our results do not suggest that family physicians should order unnecessary tests when young adults present with nonspecific symptoms, they do alert family physicians to the fact that age does not always protect against cancer. While cancer is unlikely among young adults, it must remain in the differential diagnosis, particularly when symptoms persist. Appropriate follow-up in such cases might well prevent delays in diagnosing cancer.

Limitations

The conclusions drawn from this study were based on the comments of a self-selected sample of young adult cancer patients or survivors. We acknowledge that there might be selection bias toward people who have experienced medical, psychological, or social problems throughout their experiences with cancer. We believe, however, that this does not take away from the seriousness of the issues these participants brought forward.

Conclusion

This qualitative study highlights the fact that youth can contribute to delayed diagnosis of cancer. Young people delay seeking medical attention because they feel invincible or fear a serious diagnosis. Family physicians also might delay a diagnosis of cancer because young adults do not fit the profile of typical cancer patients. Family physicians should implement appropriate follow-up procedures for patients who seem too young for cancer but present with cancer symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Kalin McClusky for helping with data analysis and Dr Sue Tatemichi for her assistance in reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Biography

Dr Miedema is Director of Research at the Dalhousie University Family Medicine Teaching Unit (FMTU) located at the Dr Everett Chalmers Regional Hospital in Fredericton, NB. Ms Easley and Mr Hamilton are part-time research assistants at the FMTU.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Cancer Care Ontario and Public Health Agency of Canada. Cancer in young adults in Canada. Toronto, Ont: Canadian Cancer Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute of Canada. Cancer incidence in young adults. Special topic from Canadian cancer statistics 2002. Toronto, Ont: National Cancer Institute of Canada; 2005. [cited 2006 September 29]. Available at: http://www.ncic.cancer.ca/ncic/internet/standard/0,3621,84658243_85787780_91035800_langId-en,00.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrett LD, Frood J, Nishri D, Ugnat AM. (Cancer in Young Adults in Canada (CYAC) Working Group). Cancer incidence in young adults in Canada: preliminary results of a cancer surveillance project. Chronic Dis Can. 2002;23(2):58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Quinzio ML, Dewar RA, Burge FI, Veugelers PJ. Family physician visits and early recognition of melanoma. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(2):136–139. doi: 10.1007/BF03403677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson A, From L, Cohen A, Tipping J. Family physicians’ knowledge of malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(6):953–957. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgess CC, Ramirez AJ, Richards MA, Love SB. Who and what influences delayed presentation in breast cancer? Br J Cancer. 1998;77(8):1343–1348. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zitzelsberger L, Grunfeld E, Graham ID. Family physicians’ perspectives on practice guidelines related to cancer control [abstract]. BMC Fam Pract. 2004;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tudiver F, Guibert R, Haggerty A, Ciampi A, Medved W, Brown JB, et al. What influences family physicians’ cancer screening decisions when practice guidelines are unclear or conflicting? [abstract]. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(9):760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner B, Myers RE, Hyslop T, Hauck WW, Weinberg D, Brigham T, et al. Physician and patient factors associated with ordering a colon evaluation after a positive fecal occult blood test. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(5):357–363. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meechan G, Collins J, Petrie K. Delay in seeking medical care for self-detected breast symptoms in New Zealand women. N Z Med J. 2002;115(1166):257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenner DC, Middleton A, Webb WM, Oommen R, Bates T. In-hospital delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87(7):914–919. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West Midlands Urological Research Group. Wallace DM, Bryan RT, Dunn JA, Begum G, Bathers S. Delay and survival in bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2002;89(9):868–878. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen ED, Harvald T, Jendresen M, Aggestrup S, Petterson G. The impact of delayed diagnosis of lung cancer on the stage at the time of operation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;12(6):880–884. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(97)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgess C, Hunter MS, Ramirez AJ. A qualitative study of delay among women reporting symptoms of breast cancer. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(473):967–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards MA, Smith P, Ramirez AJ, Fentiman IS, Rubens RD. The influence on survival of delay in the presentation and treatment of symptomatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(5-6):858–864. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tjemsland L, Soreide JA. Operable breast cancer patients with diagnostic delay—oncological and emotional characteristics. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30(7):721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sainsbury R, Johnston C, Haward B. Effect on survival of delays in referral of patients with breast-cancer symptoms: a retrospective analysis. Lancet. 1999;353(9159):1132–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGurk M, Chan C, Jones J, O’regan E, Sherriff M. Delay in diagnosis and its effect on outcome in head and neck cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43(4):281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montella M, Crispo A, D’Aiuto G, de Marco M, de Bellis G, Fabbriocini G, et al. Determinant factors for diagnostic delay in operable breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001;10(1):53–59. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200102000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Risberg T, Sorbye SW, Norum J, Wist EA. Diagnostic delay causes more psychological distress in female than in male cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 1996;16(2):995–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norman A, Sisler J, Hack T, Harlos M. Family physicians and cancer care. Palliative care patients’ perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:2009–2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sisler JJ. Delays in diagnosing cancer. Threat to the patient-physician relationship. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:857–859. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Docker MA. Cancer survival gap: Progress stalls for young adults. Wall Street Journal 2005 July 5; Sect. D:1.

- 24.Eaton G. Article main page [Realtime Cancer portal]. St John’s, Nfld: Realtime Cancer; 2006. [cited 2006 September 29]. Available at: http://www.realtimecancer.org/articles.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 25.LoBiondo-Wood G, Haber J. Nursing research: methods, critical appraisal, and utilization. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabinowitz T, Peirson R. “Nothing is wrong, doctor”: understanding and managing denial in patients with cancer. Cancer Invest. 2006;24(1):68–76. doi: 10.1080/07357900500449678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young CJ, Sweeney JL, Hunter A. Implications of delayed diagnosis in colorectal cancer. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70(9):635–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2000.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohrer TR, Fahlbusch R, Buchfelder M, Dorr HG. Craniopharyngioma in a female adolescent presenting with symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Klin Padiatr. 2006;218(2):67–71. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-921506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu CK, Chiu C, McCormack M, Olaitan A. Delayed diagnosis of cervical cancer in young women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25(4):367–370. doi: 10.1080/01443610500118814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comber H, Cronin DP, Deady S, Lorcain DO, Riordan P. Delays in treatment in the cancer services: impact on cancer stage and survival. Ir Med J. 2005;98(8):238–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tartter PI, Pace E, Frost M, Bernstein JL. Delay in diagnosis of breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1999;229(1):91–96. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199901000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer. Health Psychol. 2005;24(6):579–585. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, Laurenceau JP, Balbin E, Klimas N, et al. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):1013–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]