Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate how often family physicians see adolescents with mental health problems and how they manage these problems.

DESIGN

Mailed survey completed anonymously.

SETTING

Province of Quebec.

PARTICIPANTS

All 358 French-speaking family physicians who practise primarily in local community health centres (CLSCs), including physicians working in CLSC youth clinics, and 749 French-speaking practitioners randomly selected from private practice.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Frequency with which physicians saw adolescents with mental health problems, such as depression, suicidal thoughts, behavioural disorders, substance abuse, attempted suicide, or suicide, during the last year or since they started practice.

RESULTS

Response rate was 70%. Most physicians reported having seen adolescents with mental health problems during the last year. About 10% of practitioners not working in youth clinics reported seeing adolescents with these disorders at least weekly. Anxiety was the most frequently seen problem. A greater proportion of physicians working in youth clinics reported often seeing adolescents for all the mental health problems examined in this study. Between 8% and 33% of general practitioners not working in youth clinics said they had not seen any adolescents with depression, behavioural disorders, or substance abuse. More than 80% of physicians had seen adolescents who had attempted suicide, and close to 30% had had adolescent patients who committed suicide.

CONCLUSION

Family physicians play a role in adolescent mental health care. The prevalence of mental health problems seems higher among adolescents who attend youth clinics. Given the high prevalence of these problems during adolescence, we suggest on the basis of our results that screening for these disorders in primary care could be improved.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Évaluer à quelle fréquence les médecins de famille voient des adolescents avec des problèmes de santé mentale.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Questionnaire postal anonyme.

CONTEXTE

Province de Québec.

PARTICIPANTS

L’ensemble des 358 omnipraticiens francophones dont la pratique est principalement en Centre local de services communautaires (CLSC), incluant ceux qui travaillent en clinique jeunesse, et 749 omnipraticiens francophones choisis aléatoirement parmi les médecins de pratique privée.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES MESURÉS

La fréquence avec laquelle les médecins ont vu, durant la dernière année ou depuis qu’ils ont débuté leur pratiques médicales, des adolescents avec des problèmes de santé mentale tels que la dépression et les idéations suicidaires, les troubles du comportement, les abus de substances, les tentatives suicidaires ou le suicide.

RÉSULTATS

Le taux de réponse a été 70%. La majorité des médecins de famille ont rapporté avoir vu des adolescents ayant des problèmes de santé mentale dans la dernière année. Environ 10% des omnipraticiens (ne travaillant pas à une clinique jeunesse) ont affirmé voir au moins à chaque semaine de tels adolescents. L’anxiété est le problème de santé mentale le plus fréquemment rencontré chez les adolescents par les médecins de famille. Une plus grande proportion des médecins de clinique jeunesse ont rapporté voir fréquemment des jeunes avec des problèmes de santé mentale. Entre 8% et 33% des médecins (ne travaillant pas en clinique jeunesse) ont rapporté n’avoir vu aucun adolescent durant les 12 derniers mois souffrant de dépression, troubles du comportement, ou d’abus de substances. Depuis le début de leur pratique, plus de 80% des médecins de famille ont vu un adolescent ayant fait une tentative de suicide, et près de 30% d’entre eux ont eu un patient adolescent s’étant suicidé.

CONCLUSION

Cette étude montre que les médecins de famille jouent un rôle dans le domaine de la santé mentale adolescente. La prévalence de ces problèmes semble plus élevée parmi les adolescents consultant à une clinique jeunesse. Étant donné la prévalence des problèmes de santé mentale durant l’adolescence, notre étude suggère que le dépistage de ces conditions au niveau des soins médicaux de première ligne pourrait être amélioré.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

This study documents family physicians’ perception of the number of adolescents they see each year and the frequency with which adolescents consulted them for various medical conditions, particularly mental health problems.

A substantial proportion of family physicians not working in youth clinics reported seeing no adolescents with depression, behavioural disorders, or substance abuse during the last year (between 8% and 18% of physicians in community clinics and between 22% and 33% of private practitioners).

Given the prevalence of mental health problems during adolescence, the authors suggest on the basis of the results of this study that screening for these disorders in primary care could be improved.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Cette étude voulait connaître la perception des médecins de famille sur le nombre d’adolescents qu’ils voient chaque année et la fréquence de leurs consultations pour diverses conditions médicales, notamment les problèmes de santé mentale.

Une importante proportion des médecins de famille n’œuvrant pas dans les cliniques pour jeunes déclaraient n’avoir vu aucun adolescent souffrant de dépression, de troubles du comportement ou de consommation de drogues durant l’année précédente (8-18% des médecins pratiquant en clinique communautaire et 22-33% de ceux en pratique privée).

Compte tenu de la prévalence des problèmes de santé mentale durant l’adolescence, les auteurs se fondent sur ces résultats pour souhaiter un meilleur dépistage de ces troubles au niveau des soins primaires.

Some 10% to 25% of adolescents experience severe mental distress during adolescence.1-5 Adolescents’ mental health problems lead to extensive morbidity in many spheres of their lives and can have tragic consequences, including suicide.6-10 Research has confirmed that close to 90% of young people who commit suicide have suffered from mental health problems.9-10 The frequency with which adolescents commit suicide is particularly alarming in Québec where there are 34.4 suicides per 100 000 15- to 19-year-old boys compared with 19.3 in Canada as a whole.11

General practitioners are increasingly seen to have an important role in detecting mental illness.4,5,12-14 About 75% of adolescents consult general practitioners at least once a year for various problems.15,16 It is estimated that more than 20% of adolescents who consult primary care practitioners suffer from mental health problems,17-23 but most of these adolescents give physical health problems as the reason for consultation.17,18,24 It is essential that physicians take the initiative and raise issues related to mental health. Several studies have found that physicians tend to underdiagnose and undertreat adolescents suffering from mental health problems.5,12,13,17,25 It is thought that physicians identify less than one third of adolescents with mental health problems and that 50% to 80% of adolescents suffering from mental illnesses do not receive the care they need.4,5,12,13,25

To our knowledge, no studies on how many adolescents are seen by family physicians have been conducted in Canada, particularly in the field of mental health. The goal of this study was to document family physicians’ perceptions of the number of adolescents they see in practice each year and the frequency with which adolescents consulted them about various medical conditions, particularly mental health problems.

METHODS

We surveyed Francophone family physicians in Quebec in 2000-2001. The sample was selected from physicians listed in the database of the Collège des médecins du Québec. The study population included French-speaking general practitioners in active medical practice in Québec who obtained licences to practise medicine after 1969. Two samples were taken from this population. One sample of 749 physicians was selected randomly from among 5682 physicians exclusively in private practice. Of these, 77 were excluded because they were not eligible, could not be reached, or did not see adolescents in their practice, leaving 672 physicians. The second sample included 358 physicians who spent at least 65% of their practice time in community clinics (CLSCs). These CLSCs are public community health centres that group together various health professionals, such as physicians, nurses, social workers, and psychologists; most CLSCs offer services specifically for adolescents through youth clinics. Of these 358 physicians, 14 were excluded because we were unable to reach them or they were not eligible, leaving 344 physicians in the sample.

Data were collected through a mailed questionnaire; respondents remained anonymous. To ensure a high rate of response, 3 follow-up letters were sent to nonrespondents. The survey was composed mainly of questions to be answered on a 4- or 5-point scale. All questions were pretested on a sample of family physicians who indicated the questionnaire was understandable, pertinent, and easy to fill out. Adolescents were defined as people 12 to 17 years old. To estimate the number of adolescents seen, we asked physicians how many adolescents they had seen in an average week during the last year, how frequently adolescents visited for various physical and mental conditions during the last year, and how many adolescents they had seen for less common problems, such as suicide attempts, anorexia nervosa, or sexual abuse, since they started practice.

For the analysis, respondents were divided into 3 groups according to type of practice: private practice (n = 414), CLSC but not youth clinic practice (n = 173), and CLSC youth clinic practice (n = 110). Pearson’s chi-square test was used to determine whether the frequency of adolescents’ visits varied according to physicians’ type of practice.

RESULTS

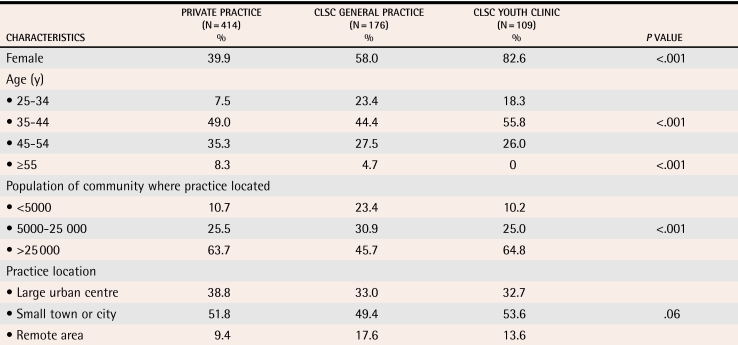

Of the 1016 eligible family physicians, 707 returned completed questionnaires, for a response rate of 69.6%. Clinic physicians were more often women and were almost 4 years younger on average than private practitioners (Table 1). A greater proportion of CLSC physicians practised in remote areas with populations of less than 5000. Regression analyses showed that physicians’ sociodemographic characteristics were not significantly related to the frequency of adolescents’ consultations for mental health problems.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents.

N = 699. Average age of physicians in private practice was 44.0 years, in CLSC general practice was 40.5 years, and in CLSC youth clinics was 40.4 years (P < .001).

Adolescent medical consultations

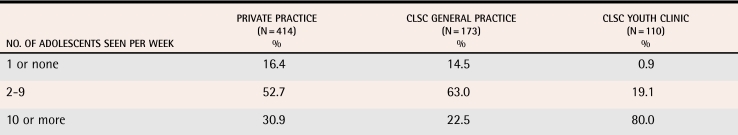

Most family physicians saw at least 2 adolescents a week (Table 2). Almost one third of private practitioners reported seeing 10 adolescents or more a week; this proportion increased to 80% among physicians working in CLSC youth clinics. We excluded from subsequent analyses 104 respondents who reported seeing 1 or no adolescents a week during the last 12 months.

Table 2. Average number of adolescents seen by physicians per week during the past year by type of practice.

N = 697, P < .001.

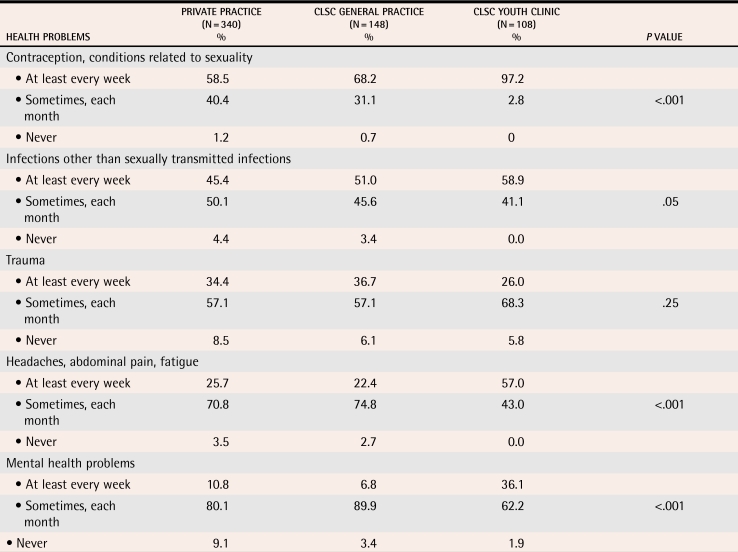

Table 3 shows the frequency with which practitioners reported seeing adolescents for 5 medical conditions. Contraception or conditions related to sexuality were the most frequently reported reason for adolescents’ visits. More than 90% of family physicians reported having seen at least 1 adolescent with a possible mental health condition during the last year. A higher proportion of youth clinic physicians reported often seeing adolescents for contraception or other reasons related to sexuality, adolescents with possible psychosomatic complaints (headaches, abdominal pain, fatigue), and adolescents with mental health problems.

Table 3.

Proportion of family physicians who had seen adolescents for various health problems during the past year by frequency of consultation and type of practice. N = 591.*

*Family physicians who reported seeing 2 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

Consultations for mental health problems

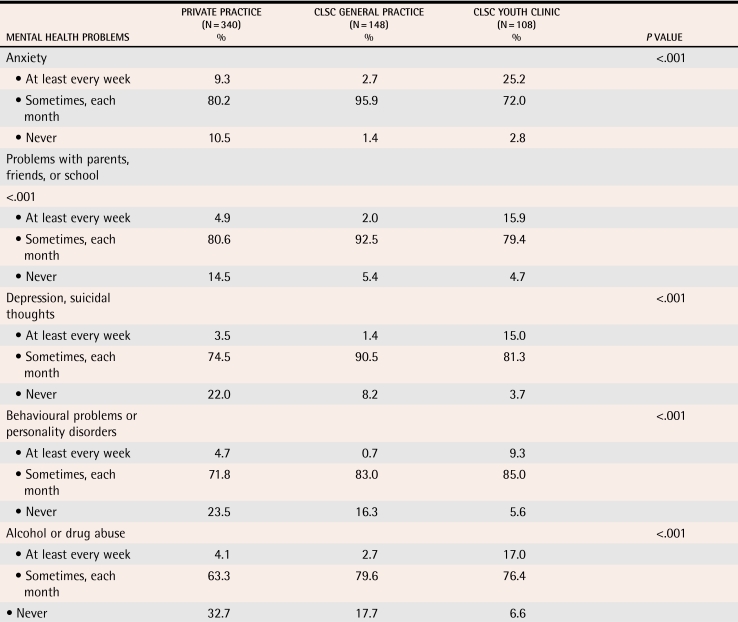

Most practitioners reported seeing at least 1 adolescent with anxiety; problems with parents, friends, or school; depression or suicidal thoughts; behavioural problems or personality disorders; or alcohol or drug abuse (Table 4). A greater proportion of youth clinic physicians saw adolescents with all types of mental health problems examined in this study.

Table 4. Proportion of family physicians who saw adolescents for mental health problems during the last year by frequency of consultation and type of practice.

N = 596.*

*Family physicians who reported seeing 2 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

Anxiety and problems with parents, friends, or school were the conditions most often seen in general practice. Adolescents with depression, suicidal thoughts, behavioural problems, or substance abuse were seen less often. Many physicians not working in youth clinics reported seeing no adolescents with these mental health problems during the last year (between 8% and 18% of CLSC general practice physicians and between 22% and 33% of private practitioners). When we restricted our analyses to physicians who saw 10 adolescents or more a week, we noted that the proportion of private practitioners who reported seeing no adolescents for behavioural problems (11.8%), depression or suicidal thoughts (15.6%), and alcohol or drug abuse (22.2%) during the last year remained high (data not shown).

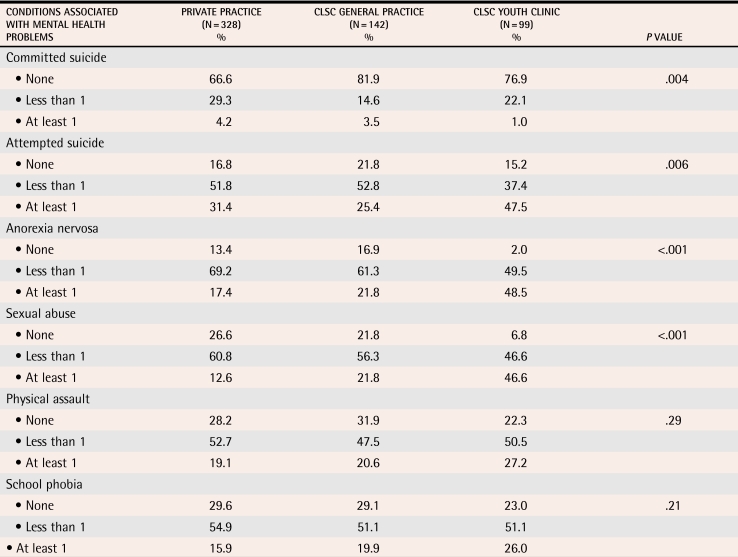

Table 5 shows data on the number of adolescents with serious mental health conditions physicians had seen since starting to practise (nearly 80% of physicians had been practising for more than 10 years). Average number of adolescents seen was calculated for a period of 2 years to take into account the small number of adolescents presenting with these conditions. Since starting practice, 20% of CLSC physicians and 33% of private practitioners reported having had at least 1 adolescent patient who committed suicide, and 4 out of 5 physicians had seen at least 1 adolescent for a suicide attempt. Youth clinic physicians reported seeing more adolescents with anorexia nervosa and sexual abuse than their colleagues did.

Table 5. Proportion of physicians who, since starting practice, had seen adolescents with conditions associated with mental health problems by type of practice.

N = 569.*

*Family physicians who reported seeing 2 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms that family physicians are consulted by adolescents. Almost one third of private practitioners said they saw at least 10 adolescents a week. It is unsurprising that a greater proportion of youth clinic physicians saw more adolescents each week. Family physicians seem to have an active role in providing mental health care to adolescents since most of them see young people with mental health conditions. In this study, about 10% of general practitioners not working in youth clinics reported often seeing adolescents with mental health problems.

More youth clinic physicians reported seeing adolescents with mental health problems, notably depression or suicidal thoughts, substance abuse, anorexia nervosa, and sexual abuse. These results suggest that the prevalence of mental health problems is higher among adolescents visiting youth clinics. This could be because adolescents feel more at ease in youth-oriented clinics and consult more readily for symptoms related to mental health. Youth clinic physicians also have an important role in adolescent sexual health care, and it is generally recognized that adolescents presenting with unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases, and sexual violence often have underlying mental health problems.7,26-29 Another explanation might be that CLSC physicians conduct more routine screening for these problems and that these physicians, who have acquired adolescent mental health expertise, get referrals from colleagues or from other health professionals working in CLSCs, especially school nurses, social workers, and psychologists. Youth clinics seem to act as intermediary resources between primary care and specialized services in the field of adolescent mental health.

Considering that more than 80% of family physicians in Quebec are private practitioners, most adolescents are consulting these physicians. This means that primary care screening for adolescents’ mental disorders depends primarily on private practice physicians. A substantial proportion of physicians not working in youth clinics (even those who see quite a few adolescents weekly) said they had not seen any adolescents for such problems as depression, behavioural disorders, or substance abuse during the past year. This might be because few adolescents visiting general practice clinics had mental health problems. We do not know the prevalence of mental health problems among respondents’ adolescent patients, but American and British studies have shown a high prevalence of mental health problems among adolescent patients in general primary care.5,12,13,17,25 This suggests that detection of adolescents’ mental health problems could be improved in Quebec. In fact, research done in other countries has concluded that most adolescents with mental problems are not diagnosed in primary care.5,12,13,17,25 This is worrying because depression, conduct disorders, and substance abuse are the 3 conditions most often identified retrospectively among adolescents who have committed suicide.9,10

Strengths

One of the strengths of this study is the fact that the sample was selected from among all Francophone general practitioners in Quebec and the response rate was high. To minimize the effect of social desirability in responses, respondents remained anonymous. This anonymity made it impossible to verify whether respondents differed from nonrespondents. Comparisons of early and late respondents did not indicate significant differences for any of the variables, especially those related to frequency of adolescents’ mental health consultations. As a result, we believe respondents did not differ significantly from the overall population under study.

Limitations

The main limitation was that data were reported by respondents and were not measured objectively. Objective and precise measurement of number of adolescents seen, frequency of consultation for mental health problems, and prevalence of these problems would require a research design that would have been difficult to apply to all general practitioners in Quebec. We believe, however, that the measures used make it possible to estimate how often general practitioners see adolescents with mental health problems. To reduce recall errors, questions generally referred to recent practice.

Conclusion

This study shows that family physicians have a role in adolescent mental health care. The prevalence of mental health problems seems to be higher among adolescents consulting in youth clinics. Given the high prevalence of mental health problems during adolescence, we suggest based on the results of our study that screening for these disorders in primary care could be improved. Family physicians should be encouraged to actively screen for mental health problems in their adolescent patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Loraine Trudeau for her assistance with data collection and processing, Sylvie Gauthier for her revision of the text, and all the physicians who participated in the survey. This study was funded by the Collège des médecins du Québec and l’Assurance Vie Desjardins-Laurentienne.

Biographies

Dr Gilbert is on staff in the Public Health Department of the Montreal Regional Health Board in Quebec.

Dr Frappier teaches in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Montreal and practises at the Hôpital Sainte-Justine.

Dr Haley is on staff in the Public Health Department of the Montreal Regional Health Board, teaches in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Montreal, and practises at the Hôpital Sainte-Justine.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Waddell C, Offord DR, Shepherd CA, Hua JM, McEwan K. Child psychiatric epidemiology and Canadian public policy-making: the state of the science and the art of the possible. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(9):825–832. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romano E, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Zoccolillo M, Pagani L. Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses and the role of perceived impairment: findings from an adolescent community sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2001;42(4):451–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts RE, Attkisson CC, Rosenblatt A. Prevalence of psychopathology among children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(6):715–725. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Post D, Carr C, Weigand J. Teenagers: mental health and psychological issues. Prim Care. 1998;25(1):181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson LA, Keller AM, Selby-Harrington ML, Parrish R. Identification and treatment of children’s mental health problems by primary care providers: a critical review of research. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1996;10(5):293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(96)80038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming JE, Boyle MH, Offord DR. The outcome of adolescent depression in the Ontario Child Health Study follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):28–33. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, Moreau D, Adams P, Greenwald S, et al. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA. 1999;281(18):1707–1713. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flisher AJ. Mood disorder in suicidal children and adolescents: recent developments [annotation]. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(3):315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Canada. Suicides: age-specific death rates, Canada and the provinces, 1950-1999. Ottawa, Ont: Statistics Canada; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson L, Churchill R, Donovan C, Garralda E, Fay J. (Members of the Adolescent Working Party, RCGP). Tackling teenage turmoil: primary care recognition and management of mental ill health during adolescence. Fam Pract. 2002;19(4):401–409. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells KB, Kataoka SH, Asarnow JR. Affective disorders in children and adolescents: addressing unmet need in primary care settings. Soc Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Direction générale du Collège des médecins du Québec. Énoncé de position: accessibilité aux soins médicaux et psychiatriques pour la clientèle adolescente. Montréal, Qué: Collège des médecins du Québec; 1999. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comité consultatif fédéral, provincial et territorial sur la santé de la population. Consultations des professionnels de la santé. In: Statistique Canada. Rapport statistique sur la santé de la population canadienne. Ottawa, Ont: Statistique Canada; 1999. pp. 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fournier M-A, Piché J. Recours aux services des professionnels de la santé et des services sociaux. In: Institut de la Statistique du Québec. Enquête sociale et de santé 1998. Québec, Qué: Institut de la Statistique du Québec; 2001. pp. 387–407. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer T, Garralda ME. Psychiatric disorders in adolescents in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:508–513. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKelvey RS, Pfaff JJ, Acres JG. The relationship between chief complaints, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation in 15-24-year-old patients presenting to general practitioners. Med J Aust. 2001;175(10):550–552. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schichor A, Bernstein B, King S. Self-reported depressive symptoms in inner-city adolescents seeking routine health care. Adolescence. 1994;29(114):379–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shrier LA, Harris SK, Kurland M, Knight JR. [cited 2006 August 24];Substance use problems and associated psychiatric symptoms among adolescents in primary care. 2003 111:699–705. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e699. Available at: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/111/6/e699. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Durant RH, Knight J, Goodman E. Factors associated with aggressive and delinquent behaviors among patients attending an adolescent medicine clinic. J Adolesc Health. 1997;21(5):303–308. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith MS, Mitchell J, McCauley EA, Calderon R. Screening for anxiety and depression in an adolescent clinic. Pediatrics. 1990;85(3):262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cappeli M, Clulow MK, Goodman JT, Davidson SI, Feder SH, Baron P, et al. Identifying depressed and suicidal adolescents in a teen health clinic. J Adolesc Health. 1995;16(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00076-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rey C, Michaud PA, Narring F, Ferron C. Les conduites suicidaires chez les adolescents en Suisse: le rôle des médecins. Arch Pédiatr. 1997;4(8):784–792. doi: 10.1016/s0929-693x(97)83424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer T, Garralda ME. Child and adolescent mental health problems in primary care. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6:287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE, Walters EE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders. II: teenage parenthood. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(10):1405–1411. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrier LA, Harris SK, Beardslee WR. Temporal associations between depressive symptoms and self-reported sexually transmitted disease among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:599–606. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gosselin C, Lanctôt N, Paquette D. La grossesse à l’adolescence, conséquences de la parentalité, prévalence, caractéristiques associées à la maternité et programmes de prévention en milieu scolaire. In: Vitaro F, Gagnon C, rédacteurs. Prévention des problèmes d’adaptation chez les enfants et les adolescents: les problèmes externalisés. Québec, Qué: Presses de l‘Université du Québec; 2001. pp. 461–492. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otis J, Médico D, Lévy JJ. La prévention des maladies transmissibles sexuellement et de l’infection par le VIH chez les adolescents. In: Vitaro F, Gagnon C, rédacteurs. Prévention des problèmes d’adaptation chez les enfants et les adolescents: les problèmes externalisés. Québec, Qué: Presses de l‘Université du Québec; 2001. pp. 493–555. [Google Scholar]