Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To document with whom family physicians communicate when evaluating adolescents with mental health problems, to whom they refer these adolescents, and their knowledge and perceptions of the accessibility of mental health services in their communities.

DESIGN

Mailed survey completed anonymously.

SETTING

Province of Quebec.

PARTICIPANTS

All general practitioners who reported seeing at least 10 adolescents weekly (n = 255) among 707 physicians who participated in a larger survey on adolescent mental health care in general practice.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Whether family physicians communicated with people (such as parents, teachers, or school nurses) when evaluating adolescents with mental health problems. Number of adolescents referred to mental health services during the last year. Knowledge of mental health services in the community and perception of their accessibility.

RESULTS

When asked about the last 5 adolescents seen with symptoms of depression or suicidal thoughts, depending on type of practice, 9% to 19% of physicians reported routinely communicating with parents, and 22% to 32% reported not contacting parents. Between 16% and 43% of physicians referred 5 adolescents or fewer to mental health services during a 12-month period. Most practitioners reported being adequately informed about the mental health services available in their local community clinics. Few physicians knew about services offered by private-practice psychologists, child psychiatrists, or community groups. Respondents perceived mental health services in community clinics (CLSCs) as the most accessible and child psychiatrists as the least accessible services.

CONCLUSION

Few physicians routinely contact parents when evaluating adolescents with serious mental health problems. Collaboration between family physicians and mental health professionals could be improved. The few referrals made to mental health professionals might indicate barriers to mental health services that could mean many adolescents do not receive the care they need. The lack of access to mental health services, notably to child psychiatrists, reported by most respondents could explain why some physicians choose not to refer adolescents.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Les objectifs de cette recherche étaient de documenter avec qui les omnipraticiens communiquent lorsqu’ils évaluent un adolescent ayant un problème de santé mentale, vers qui ils les dirigent, et quelles sont leurs connaissances et perceptions de l’accessibilité des services en santé mentale.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Questionnaire postal anonyme.

CONTEXTE

Province de Québec.

PARTICIPANTS

Tous les omnipraticiens (n = 255) ayant vu au moins 10 adolescents par semaine parmi les 707 répondants ayant participé à une étude plus vaste sur la santé mentale des adolescents.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES MESURÉS

Si les omnipraticiens ont communiqué durant la dernière année avec les parents, les professeurs ou les infirmières scolaires, lors de l’évaluation d’un adolescent ayant un problème de santé mentale. Le nombre aiguillés durant la dernière année vers des ressources en santé mentale. La connaissance des services en santé mentale et la perception de l’accessibilité à ces services.

RÉSULTATS

Concernant les 5 derniers adolescents vus avec une dépression ou idéation suicidaire, de 9 à 19 % des médecins, selon le type de pratique, ont répondu avoir communiqué automatiquement avec les parents; de 22 à 32 % ont affirmé n’avoir communiqué à aucune reprise. Durant la dernière année, de 16 à 43 % des médecins ont aiguillé 5 adolescents ou moins vers des ressources en santé mentale. La majorité des omnipraticiens ont répondu être informés adéquatement concernant les services en santé mentale offerts par le CLSC. Peu de médecins connaissent adéquatement les services offerts par les psychologues, les pédopsychiatres ou les organismes communautaires. Les CLSC étaient perçus comme les ressources les plus accessibles et la pédopsychiatrie, comme la moins accessible.

CONCLUSION

Peu de médecins communiquent automatiquement avec les parents lors de l’évaluation d’un adolescent souffrant d’un problème sérieux de santé mentale. La collaboration entre les médecins de famille et les professionnels en santé mentale pourrait être améliorée. Le faible nombre d’aiguillages peut indiquer que des barrières empêchent l’intégration des services en santé mentale, privant possiblement plusieurs adolescents de soins requis. Le manque d’accessibilité, particulièrement aux pédopsychiatres, peut expliquer pourquoi certains médecins ont choisi de ne pas aiguiller des adolescents.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Between 10% and 25% of adolescents experience mental health problems that could have serious consequences, such as suicide.

This study found that few family physicians in Quebec communicated routinely with parents, even when adolescents consulted with serious mental health problems, such as symptoms of depression, suicidal thoughts, or suicide attempts.

Collaboration between family physicians and other mental health professionals could be improved; a substantial number of family physicians referred very few adolescents to mental health services.

The lack of access to mental health services (notably child psychiatrists) reported by most respondents could explain why some physicians choose not to refer adolescents.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Entre 10 et 25% des adolescents connaissent des problèmes de santé mentale pouvant avoir des conséquences aussi graves que le suicide.

Cette étude a montré que peu de médecins de famille du Québec communiquent de façon routinière avec les parents, même lorsque les adolescents présentent de sérieux problèmes de santé mentale, comme des symptômes de dépression, des idées suicidaires ou des tentatives de suicide.

La collaboration entre les médecins de famille et les autres professionnels de la santé mentale pourrait être améliorée; un important nombre de médecins de famille dirigent très peu d’adolescents vers des services de santé mentale.

Le peu d’accès aux services de santé mentale (notamment aux psychiatres pédiatriques), une difficulté mentionnée par la plupart des répondants, pourrait expliquer pourquoi certains médecins choisissent de ne pas diriger les adolescents vers ces services.

Mental health problems are a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality among adolescents.1-5 Between 10% and 25% of adolescents experience mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, and conduct disorders.6-10 The high prevalence of mental health problems during adolescence and the potential for serious consequences (one being suicide) are strong arguments for early detection and appropriate management of adolescents’ mental problems.9-12

In a background paper on adolescent medical and psychiatric care, the Collège des médecins du Québec recommended that family physicians be able to diagnose adolescent mental health problems; evaluate social, family, and environmental components of illness; institute appropriate treatment or refer to specialized services when necessary; and provide follow-up care.13 In order to do this, the College recommended that family physicians caring for adolescents be connected to and supported by mental health teams composed of child psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers.13 The College emphasized a model of mental health care that could minimize barriers between medical professionals and mental health professionals and make the best possible use of child psychiatrists’ expertise.13

Quebec mental health resources include those in public community health centres (CLSCs) that group together physicians, nurses, social workers, and psychologists (most CLSCs offer services specifically to adolescents through youth clinics); private psychologists; local community youth groups; hospital child psychiatry services; and youth protection agencies.

Little is known about how primary care physicians refer their adolescent patients to mental health services in Quebec. American and British studies indicate that referrals to mental health professionals vary substantially in general practice10,14-17 and that availability and accessibility of mental health services for adolescents are limited.11,12,14-16,18,19

This study sought to document with whom family physicians communicate when evaluating adolescents with possible mental health problems and to whom they refer these adolescents. We also investigated physicians’ knowledge about and perception of the accessibility of mental health services in their communities.

METHODS

Data for this paper came from a mailed survey completed anonymously by Quebec French-speaking general practitioners. The survey was conducted in 2000-2001 on 2 samples of practitioners, those exclusively in private practice and those who spent at least 65% of their clinical time in CLSCs. Of 1016 eligible physicians, 707 participated for a response rate of 70% (more information about study methods is provided on page 1441).

Analyses for this paper were based on data from 255 practitioners who reported seeing at least 10 adolescents per week during their last 12 months of practice. Among these 255, 128 were in private practice, 39 in CLSC general practice, and 88 in CLSC youth clinic practice. We specifically examined whether, during the last year, physicians had sought the collaboration of parents, teachers, school nurses, CLSC professionals, or youth protection workers when evaluating adolescents with possible mental health problems; the number of adolescents physicians had referred to CLSC mental health professionals, private practice psychologists, child psychiatrists, youth protection agencies, or community groups during the last year; and physicians’ knowledge of mental health services in their region and whether they perceived these services to be easily accessible. All measures were taken from physicians’ answers to closed-ended questions pretested for clarity.

RESULTS

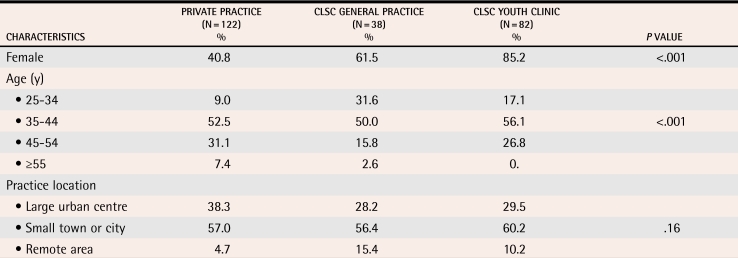

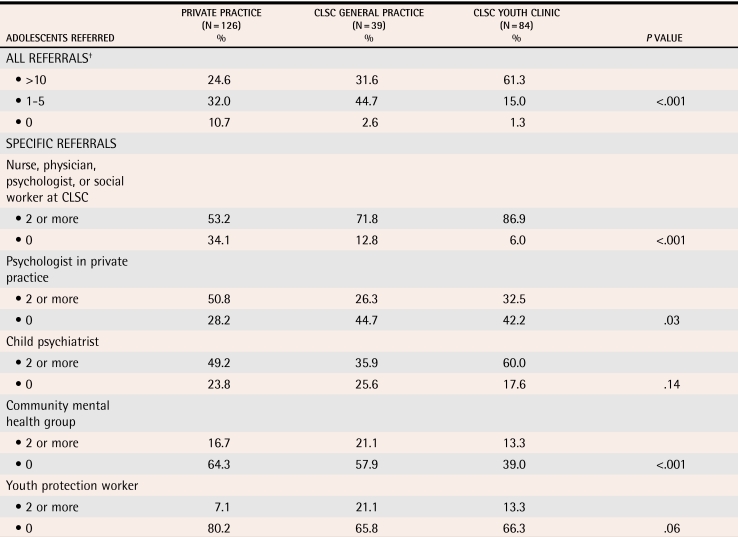

Compared with private practitioners, CLSC physicians were younger, more often women, and somewhat more likely to practise in remote areas (Table 1). We did regression analyses to examine whether age, sex, and size of community where physicians practised influenced their communication and referral practices. None of these variables turned out to be significant; they were thus not retained as control variables in subsequent analyses.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents (N = 242),* by type of practice.

Average age of physicians in private practice was 43.1 years, in CLSC general practice was 38.3 years, and in CLSC youth clinics was 40.5 years (P<.001)

CLSC—community health centre.

*General practitioners who reported seeing 10 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

Communication

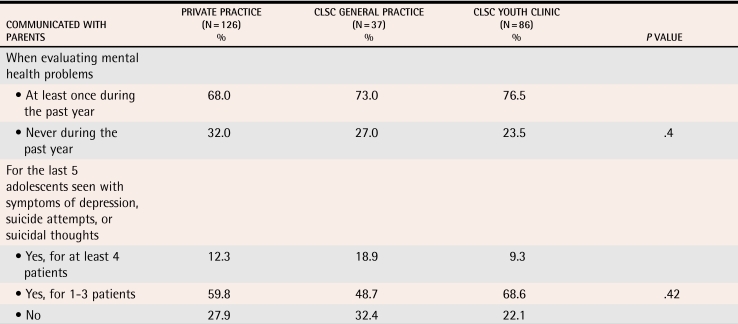

More than two thirds of physicians reported contacting—at least once during the last year—the parents of adolescents presenting with mental health problems (Table 2). The frequency with which physicians communicated with parents when consulted by adolescents with symptoms of depression, suicidal thoughts, or suicide attempts varied greatly. When asked about the last 5 adolescents seen with these conditions, 9% to 19% of physicians reported routinely communicating with parents, and 22% to 32% reported not contacting parents. Although type of practice was not associated with whether physicians communicated with parents, it influenced the extent to which they communicated with other professionals (Table 3). Physicians in CLSCs, especially those working in youth clinics, were more likely to report having contacted CLSC mental health staff, school nurses, or teachers when evaluating adolescents with mental health problems.

Table 2.

Percentage of family physicians (N = 249)* who reported communicating with parents when evaluating adolescents with mental health problems, by type of practice

CLSC—community health centre.

*General practitioners who reported seeing 10 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

Table 3.

Percentage of family physicians (N = 249)* who reported contacting people other than parents at least once during the last year when evaluating adolescents with mental health problems, by type of practice

CLSC—community health centre.

*General practitioners who reported seeing 10 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

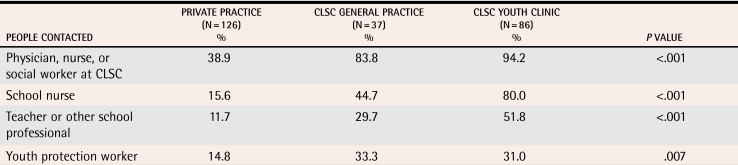

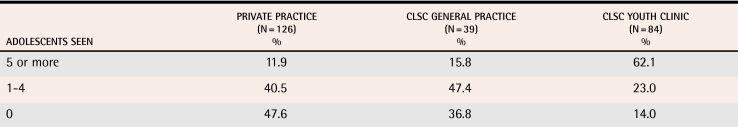

Referral practices

Between 25% and 61% of respondents reported referring more than 10 adolescents to mental health services during a 12-month period (Table 4). During the same period, between 15% and 45% of physicians referred 5 adolescents or fewer. Analysis of data on physicians who reported seeing adolescents with mental health problems at least weekly showed that 24% of practitioners not working in youth clinics had referred 5 adolescents or fewer during the last year (data not shown).

Table 4.

Percentage of family physicians (N = 249)* who referred adolescents with symptoms of mental health problems to mental health services during the last year, by type of practice

CLSC—community health centre.

*General practitioners who reported seeing 10 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

†Includes professionals working in CLSCs, psychologists in private practice, child psychiatrists, community mental health groups, and youth protection agencies.

Physicians in CLSC practice were more likely than physicians in private practice to refer adolescents with mental health problems to professionals within their own institutions. Private practitioners were more likely than CLSC physicians to refer to psychologists in private practice. A greater proportion of physicians in youth clinics made referrals to mental health professionals in general and to child psychiatrists and community groups in particular.

Between 52% and 85% of family physicians reported they had seen during the last year at least 1 adolescent with mental health problems referred by colleagues or other professionals (Table 5). Youth clinic physicians were more likely to have seen referred adolescents.

Table 5.

Percentage of family physicians (N = 249)* who had seen adolescents with mental health problems referred by other professionals during the last year, by type of practice (P < .001)

CLSC—community health centre.

*General practitioners who reported seeing 10 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

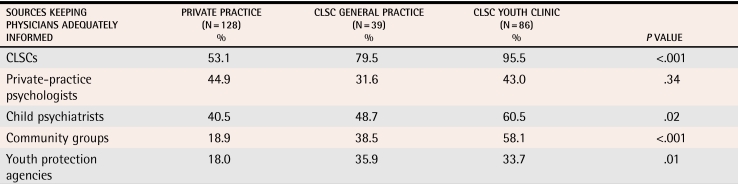

Knowledge of mental health services

Physicians seem to be most familiar with the services offered by CLSCs. The percentage of practitioners who felt adequately informed about the mental health services offered in their local CLSCs ranged from 53% for physicians in private practice to 95% for physicians in youth clinic practice (Table 6). The percentage of physicians who reported being adequately informed about services offered by psychologists in private practice and child psychiatrists ranged from 32% to 60%. The percentage of respondents who felt adequately informed about community groups and youth protection agencies ranged from 18% to 58%.

Table 6.

Percentage of family physicians (N = 253)* who reported being adequately† informed about mental health services in their region, by type of practice

CLSC—community health centre.

*Family physicians who reported seeing 10 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

†Quite well informed and very well informed.

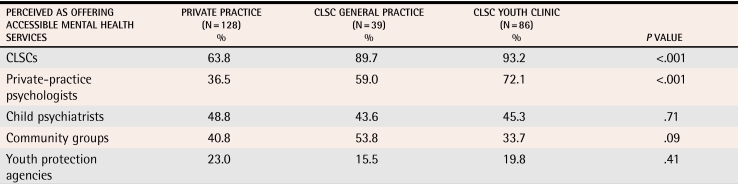

Perceived accessibility of mental health services

Respondents perceived mental health services in CLSCs to be the most accessible and child psychiatrists to be the least accessible (Table 7). A higher proportion of CLSC physicians than private practitioners thought that mental health services offered by CLSCs and community groups were fairly or very accessible. A lack of knowledge about community groups and youth protection agencies might explain the fact that almost one third of practitioners did not have an opinion on the accessibility to these services (data not shown).

Table 7.

Percentage of family physicians (N = 252)* who perceived mental health services as being accessible,† by type of practice

CLSC—community health centre.

*Family physicians who reported seeing 10 or more adolescents per week during the last year.

†Fairly or very accessible.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that, although most family physicians had communicated with parents at least once during the last year when evaluating adolescents with mental health problems, few physicians did so routinely, even when these adolescents had serious mental health problems, such as symptoms of depression or suicidal thoughts, or suicide attempts. The dilemma faced by front-line health professionals—the obligation to provide confidential care combined with the need to obtain additional information—could partially explain why some physicians do not contact parents.

While the general principle of confidentiality should be respected, it would be advantageous for physicians to contact parents of adolescents with mental health problems more frequently because parents might be able to add relevant information on family history, early childhood behaviour and experiences, and current situations. Contact with parents could also foster collaboration during treatment and follow-up. It is possible that, given adolescents’ desire for autonomy, family physicians underestimate the key role parents play in their lives. After discussing the issue, many adolescents agree that their parents should be informed about their mental health difficulties. Consultations involving parents and their adolescents could help parents become better acquainted with their children’s problems and could help them to support their young people in time of need.

Another important finding is that physicians’ referral practices vary. Compared with private-practice physicians and physicians in CLSC general practice, physicians in youth clinics refer more adolescents to mental health services and see more adolescents with mental health problems referred by colleagues or other professionals. As shown elsewhere (page 1441), it is likely that the prevalence of mental health problems is higher among adolescents consulting in youth clinics. Physicians in youth clinics probably act as intermediary resources between primary care and specialized mental health resources, help forge closer links with youth mental health teams in hospitals and CLSCs, and are available to their front-line colleagues who deal with adolescents in difficulty. Private practitioners who have acquired specific expertise in the field of adolescent health seem to have a similar role.

More than 40% of family physicians who see a substantial number of adolescents but do not work in youth clinics referred 5 adolescents or fewer to mental health services during a 1-year period. Several hypotheses could explain the low number of referrals. First, the prevalence of mental health problems might be low among these respondents’ adolescent clientele or mental health problems might be underdetected. This theory is not supported by British and American studies, which show that the prevalence of mental health problems among adolescents who use primary care services is high.21-24 When we restricted our analysis to physicians who see adolescents with mental health problems weekly, we still found a low number of referrals. Second, physicians might have thought they could themselves provide follow-up care without referral to specialized mental health services. Studies show that most adolescents with mental health problems do not receive the treatment they need.10-12,18,21 For many adolescents, problems are more than “teenage blues”; these problems need treatment that can be complex and require expertise. Third, it could be that physicians are inadequately informed about mental health services. Our results suggest that family physicians could be more knowledgeable about adolescent services offered by mental health professionals. The proportion of physicians who said they were poorly informed about these services was high, even among physicians in youth clinics (except for services offered in their own institutions). Finally, perceived difficulty in accessing services could explain why many family physicians chose not to refer. Lack of access to child psychiatrists was reported by many respondents as a serious problem. Poor access to mental health services is often cited as an important barrier to delivering mental health care.11-12,14-16,19

Strengths of the study

The practices documented in this study are those of general practitioners who see at least 10 adolescents weekly. We took many precautions to minimize measurement errors. The wording of questions was pretested for clarity. To minimize recall errors, questions asked about the recent past (last 12 months of practice). The survey was anonymous to decrease social desirability bias in responses. The anonymous nature of the questionnaire made it impossible to verify whether respondents differed from nonrespondents. Comparisons between early and late respondents did not indicate significant differences in any study variables.

Conclusion

This study shows that few physicians routinely contact parents when evaluating adolescents with mental health problems. It also suggests that collaboration between family physicians and other mental health professionals could be improved, as a substantial number of physicians referred only a few adolescents. The low number of referrals might indicate barriers to the integration of mental health services into general care so that many adolescents do not receive the care they need. The lack of access to mental health services, notably to child psychiatrists, reported by most respondents could explain why some physicians chose not to refer adolescents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Loraine Trudeau for her assistance in data collection and processing, Sylvie Gauthier for her revision of the text, and all the physicians who participated in the survey. This study was funded by the Collège des médecins du Québec and l’Assurance Vie Desjardins-Laurentienne.

Biographies

Dr Maheux teaches in the Department of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Montreal.

Dr Haley is on staff in the Public Health Department of the Montreal Regional Health Board, teaches in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Montreal, and practises at the Hôpital Sainte-Justine.

Dr Frappier teaches in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Montreal and practises at the Hôpital Sainte-Justine.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Fleming JE, Boyle MH, Offord DR. The outcome of adolescent depression in the Ontario Child Health Study Follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):28–33. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, Moreau D, Adams P, Greenwald S, et al. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA. 1999;281(18):1707–1713. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flisher AJ. Mood disorder in suicidal children and adolescents: recent developments [annotation]. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1999;40(3):315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romano E, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Zoccolillo M, Pagani L. Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses and the role of perceived impairment: findings from an adolescent community sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2001;42(4):451–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts RE, Attkisson CC, Rosenblatt A. Prevalence of psychopathology among children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(6):715–725. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waddell C, Offord DR, Shepherd CA, Hua JM, McEwan K. Child psychiatric epidemiology and Canadian public policy-making: the state of the science and the art of the possible. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(9):825–832. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Post D, Carr C, Weigand J. Teenagers: mental health and psychological issues. Prim Care. 1998;25(1):181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson LA, Keller AM, Selby-Harrington ML, Parrish R. Identification and treatment of children‘s mental health problems by primary care providers: a critical review of research. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1996;10(5):293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(96)80038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson L, Churchill R, Donovan C, Garralda E, Fay J. (Adolescent Working Party, RCGP). Tackling teenage turmoil: primary care recognition and management of mental ill health during adolescence. Fam Pract. 2002;19(4):401–409. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells KB, Kataoka SH, Asarnow JR. Affective disorders in children and adolescents: addressing unmet need in primary care settings. Soc Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collège des médecins du Québec. Background paper: access to medical and psychiatric care for the adolescent population. Montreal, Que: Collège des médecins du Québec; 1999. [cited 2006 October 6]. Available at: http://www.cmq.org/DocumentLibrary/UploadedContents/CmsDocuments/Position%20soins%20psych%20ados%20ANG%2099.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rushton J, Bruckman D, Kelleher K. Primary care referral of children with psychosocial problems. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:592–598. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rushton JL, Clark SJ, Freed GL. Primary care role in the management of childhood depression: a comparison of pediatricians and family physicians. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4):957–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olson AL, Kelleher KJ, Kemper KJ, Zuckerman BS, Hammond CS, Dietrich AJ. Primary care pediatricians‘ roles and perceived responsibilities in the identification and management of depression in children and adolescents. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1(2):91–98. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0091:pcprap>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garner W, Kelleher KJ, Wasserman R, Childs G, Nutting P, Lillienfeld H, et al. [cited 2006 August 28];Primary care treatment of pediatric psychosocial problems: a study from pediatric research in office settings and ambulatory sentinel practice network. 2000 106(4):44–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.e44. Available at: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/106/4/e44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Costello EJ. Primary care pediatrics and child psychopathology: a review of diagnostic, treatment, and referral practices. Pediatrics. 1986;78(6):1044–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer T, Garralda ME. Child and adolescent mental health problems in primary care. Adv Psychiatric Treat. 2000;6:287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walders N, Childs GE, Comer D, Kelleher KJ, Drotar D. Barriers to mental health referral from pediatric primary care settings. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9(10):677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer T, Garralda ME. Psychiatric disorders in adolescents in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:508–513. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKelvey RS, Pfaff JJ, Acres JG. The relationship between chief complaints, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation in 15-24-year-old patients presenting to general practitioners. Med J Aust. 2001;175(10):550–552. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schichor A, Bernstein B, King S. Self-reported depressive symptoms in inner-city adolescents seeking routine health care. Adolescence. 1994;29(114):379–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrier LA, Harris SK, Kurland M, Knight JR. [cited 2006 August 28];Substance use problems and associated psychiatric symptoms among adolescents in primary care. 2003 111(6):699–705. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e699. Available at: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/111/6/e699. [DOI] [PubMed]