Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To review the presentation of endometriosis, steps to diagnosis, and medical and surgical management options.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

MEDLINE was searched from January 1996 to November 2004, EMBASE from January 1996 to January 2005, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for the 4th quarter of 2004.

MAIN MESSAGE

Endometriosis is a common, progressive disease with an estimated prevalence of 10%. It can cause dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, low back pain, and infertility. It can be diagnosed on clinical grounds and treated without laparoscopy provided pregnancy is not desired. First- and second-line medical treatments are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, combined oral contraceptive pills, progestins, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, and androgens. Surgical options should be considered when these medications are ineffective or if pregnancy is desired.

CONCLUSION

Family physicians have an important role in diagnosing and treating women with endometriosis.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Faire le point sur les manifestations cliniques de l’endométriose, les étapes du diagnostic et les options de traitement par médication et chirurgical.

SOURCES DE L’INFORMATION

On a consulté MEDLINE de janvier 1996 à novembre 2004, EMBASE de janvier 1996 à janvier 2005 et la base de données Cochrane sur les revues systématiques du quatrième trimestre de 2004.

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

L’endométriose est une maladie progressive fréquente; sa prévalence est estimée à 10 %. Elle peut être responsable de dyspareunie, de dysménorrhée, de douleurs lombaires et d’infertilité. Elle peut être diagnostiquée cliniquement et traitée sans laparoscopie, à condition qu’on n’envisage pas de grossesse. Le traitement par médication de première et de deuxième intention inclut les anti-inflammatoires non stéroïdiens, les anticonceptionnels oraux combinés, les progestatifs, les agonistes de la gonadolibérine et les androgènes. La chirurgie devrait être envisagée lorsque ces médicaments sont inefficaces ou si une grossesse est désirée.

CONCLUSION

Le médecin de famille a un rôle important à jouer dans le diagnostic et le traitement des femmes atteintes d’endométriose.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Endometriosis affects about 10% of women, although many do not have any of the symptoms of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, low back pain, or infertility.

Diagnosis is usually based on history, as results of physical examination are often negative. Ultrasound scans (especially transvaginal) might be helpful, but laparoscopy is the definitive investigation.

If pregnancy is not desired, medical treatment is indicated and can be started without laparoscopic confirmation. If pregnancy is desired, surgery is the only effective means of managing infertility.

First-line medical treatments include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and low-dose combined oral contraceptives. Second-line drugs include progestins, androgens, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

L’endométriose affecte environ 10% des femmes, quoique plusieurs d’entre elles n’aient aucun symptôme de dysménorrhée, de dyspareunie, de douleurs lombaires ou d’infertilité.

L’historique suffit généralement pour poser le diagnostic, les résultats de l’examen physique étant souvent négatifs. L’ultrasonogramme (surtout transvaginal) peut être utile, mais la laparoscopie est l’examen définitif.

Si une grossesse n’est pas envisagée, le traitement par médication est indiqué et il peut être instauré sans confirmation laparoscopique. Si une grossesse est désirés, la chirurgie est la seule façon efficace de traiter l’infertilité.

Les traitements par médication de premier recours incluent les anti-inflammatoires non stéroïdiens et les contraceptifs oraux combinés. Le médicaments de seconde intention comprennent les progestatifs, les androgènes et les agonistes de la gonadolibérine.

Endometriosis is a common cause of chronic pelvic pain in women presenting in primary care. It is a progressive disease and can be difficult to diagnose because its symptoms are common to other causes of pelvic pain. Endometriosis is a condition where endometrial tissue is found outside the uterus and often causes pain or infertility. The prevalence of endometriosis is not known precisely, but it is estimated to affect around 10% of all women1 and 2% to 40%2 of women who are infertile. Incidence peaks at 40 years of age,1 and symptoms usually resolve with menopause. Most endometrial deposits are found on the ovaries, peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, pouch of Douglas, and retrovaginal septum. Deposits have also been found in the rectum and bladder and even within the lungs and brain.3

Endometriosis is common and can severely affect quality of life and fertility. Hence, an approach to its diagnosis and an understanding of the medical and surgical treatment options for it are important for family physicians to know. The approach in this article is based on a review of the literature on endometriosis and our own clinical experience.

Case 1

Jennifer, a 36-year-old woman who has had one child, presents with a long-standing history of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia. She takes an oral contraceptive and maximum doses of ibuprofen during menstruation. She comes to see you now because she is finding her dysmenorrhea severe enough to affect her work and home life. Her daughter was born when she was 26 years old after 2 years of unprotected intercourse. Her symptoms have never been investigated. She does not want to have another child.

Case 2

Michelle, a 29-year-old woman who has never been pregnant, comes to you after having a laparoscopic appendectomy. She is concerned because, after the operation, her surgeon told her that she had endometriosis. She says she has no pelvic discomfort and her menses are regular and pain free. She is sexually active and uses condoms for contraception. She has been reading about endometriosis and wonders whether she should be treated, particularly as she is concerned about future fertility.

Sources of information

MEDLINE was searched from January 1996 to November 2004, EMBASE from January 1996 to January 2005, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for the 4th quarter of 2004 using the search term endometriosis with the subheadings diagnosis, therapy, and drug therapy, and limited to review articles (including systemic reviews) involving human female subjects for the years 1998 to 2004. Articles with a primary care or family practice focus were selected. The British Medical Journal Clinical Evidence was searched, and results were compared with results from the other databases. The Guidelines Advisory Committee’s Recommended Practice Guidelines for Endometriosis were also searched.

Main Message Presentation

The clinical presentation of women with endometriosis varies. Many women are asymptomatic and are recognized as having endometriosis only when they are being investigated for infertility. Endometriosis can present with any combination of dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, low back pain, pelvic pain, pelvic mass, or infertility. Pelvic pain often increases premenstrually. Patients might also have menorrhagia or metrorrhagia (uterine bleeding at any time other than menstruation). Bowel and bladder symptoms are sometimes present also, making endometriosis difficult to distinguish from irritable bowel syndrome or interstitial cystitis.

Endometriosis should be considered in any woman who presents with dysmenorrhea after years of pain-free cycles. There appears to be a familial tendency. Other risk factors include early menarche, late menopause, and heavy menstrual flow. Protective factors include use of oral contraceptive pills, smoking, and low body mass index.4 Epidemiologic evidence from large cohort studies suggests that endometriosis is an independent risk factor for epithelial ovarian cancer. Risk of malignant transformation of ovarian endometriosis is estimated at 2.5%.5

Pathogenesis

There are several theories about the causes of endometriosis. The most widely accepted is that retrograde menstrual flow through the fallopian tubes implants on the peritoneal surfaces.6 Other theories involve celomic metaplasia (where peritoneal cells change into endometrial glandular cells) and hematologic and lymphatic spread.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of endometriosis is usually made on the basis of clinical history, as results of physical examination are often normal.7 Clinicians should palpate for uterine and adnexal tenderness, a fixed retroverted uterus, pelvic masses, and nodularity along the uterosacral ligaments. Most women have normal pelvic findings. The most common finding is tenderness on palpation of the posterior fornix. Physical examination should also be directed toward ruling out other causes of pelvic pain, primarily bowel and bladder conditions. The workup should include urinalysis, pregnancy test, Pap smear, and vaginal and endocervical swabs.6

Pelvic ultrasound scans might be helpful for diagnosis, particularly if an endometrioma is identified (level III evidence). They also might help exclude other causes of pelvic pain, such as fibroids and ovarian cysts. Transvaginal ultrasound scans are better for visualizing the uterine cavity and endometrium, but transabdominal scans are preferred when large pelvic masses are suspected.6 Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are sometimes useful, particularly for characterizing pelvic masses, but should not be ordered routinely.

The most definitive test for diagnosing endometriosis is laparoscopic visualization of typical lesions and biopsy (level III evidence), but it is not always necessary. Pain does not always correlate with severity of findings on diagnostic laparoscopy. Of all lesions seen and biopsied, only 45% are confirmed to be endometriosis.7 Negative findings of diagnostic laparoscopy are accurate for excluding endometriosis.6

Treatment

Endometriosis does not need to be treated unless it is symptomatic. Medical and surgical treatment have been found equally effective, except for treatment of infertility.5 If a woman is not trying to conceive and has no evidence of a pelvic mass on examination, empiric medical treatment without laparoscopic confirmation can be tried on the basis of clinical suspicion. If pregnancy is desired, surgical treatment is necessary, as no pharmacologic method has been shown to restore or maintain fertility4,8 (level I evidence).

Medical treatment options

Most treatments aim to reduce the symptoms of endometriosis; none have been shown to completely prevent recurrence of symptoms once treatment is stopped. Symptoms recur 37% of the time with mild disease and 74% of the time with severe disease.7 The presumed hormonal responsiveness of endometriosis forms the basis of most medical treatments. As no medical treatment has demonstrated superiority over another (level I evidence), choice of treatment is based on side effect profile, cost, and personal preference.9,10 Most drugs improve symptoms in 80% to 90% of patients.11

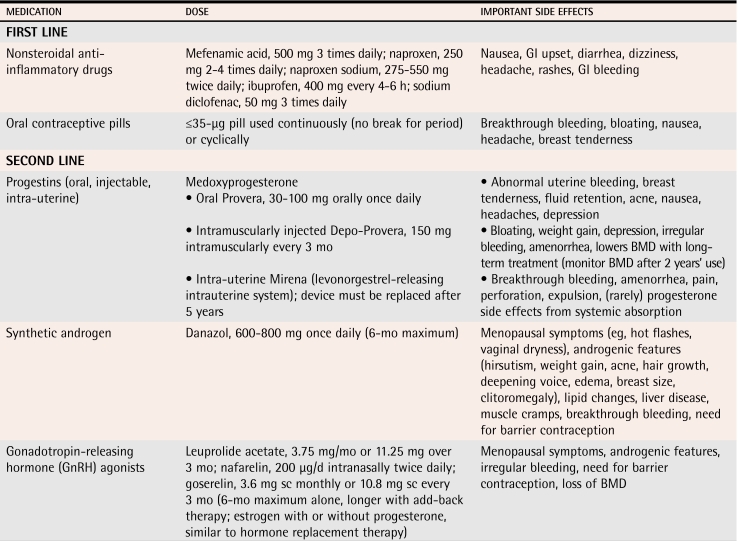

First-line options are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and low-dose combined oral contraceptive pills (COCP). If patients do not respond or respond inadequately after 3 months, second-line treatments that include progestins (oral, injectible, and intra-uterine), androgens, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH) analogues should be tried. These are all equally effective in reducing moderate and severe pain in endometriosis.6 Some of these medications can be used only short term, but their use might allow the disease to be controlled to the extent that other medications can be used for maintenance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Medical therapies for endometriosis

BMD—bone mineral density, GI—gastrointestinal, sc—subcutaneous.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

While patients have symptoms, NSAIDs (especially 500 mg of mefenamic acid orally 3 times daily) offer substantial pain relief to about 72% of patients11 (level I evidence). Symptoms often recur after discontinuation of therapy.

Combined oral contraceptive pills.

These pills suppress luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone to prevent ovulation. They also have a direct effect on endometrial tissue, causing atrophy. The COCPs can be used continuously or cyclically.

Progestins.

Progestins are similar to COCPs with regard to their effect on follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and endometrial tissue. They often have more bothersome side effects than COCPs, but they are effective and useful, particularly when estrogen therapy is contraindicated. Progestins can be given orally on a daily basis or injected. Recent evidence has indicated that the Mirena intrauterine system is also effective at improving symptoms of endometriosis12 (level II evidence).

Danazol.

Danazol is highly effective at alleviating symptoms of endometriosis, but is limited by its side effects. Danazol is a synthetic androgen that inhibits luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, producing a relatively hypoestrogenic state and endometrial atrophy. Side effects from decreased estrogen levels include headaches, flushing, sweating, and atrophic vaginitis, and androgenic side effects include acne, hirsutism, edema, weight gain, and voice changes.

A typical starting dose of danazol is 400 mg twice daily, but it can be titrated downward as long as amenorrhea and symptom relief are maintained. Use of this medication is usually limited to 6 months secondary to side effects.6

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.

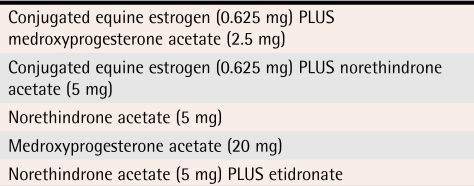

These drugs inhibit secretion of gonadotropins and have hypoestrogenic side effects similar to danazol. They have been associated with bone loss, a side effect that usually limits their use to 6 months. These GnRH agonists can be used for longer than 6 months if low-dose estrogen “add-back” therapy is given4 (level III evidence) (Table 26).

Table 2.

Examples of add-back daily hormone regimens

Reprinted with permission from Bell and Colledge.6

Many forms of GnRH agonists are available; all are quite expensive. Leuprolide acetate is given as a 3.75-mg intramuscular injection once a month. Goserelin is given at a dose of 3.6 mg subcutaneously every 28 days. Nafarelin, a nasal spray, is given twice daily.

Surgical treatment options

Surgical treatments are generally reserved for women who wish to become pregnant and women whose symptoms do not respond to medical therapy. Surgical options include excision or ablation of endometrial implants (endocoagulation, electrocautery, or laser treatment) and have a 50% to 80% success rate in reducing symptoms.13,14 No one surgical technique has proven superior to another. Unfortunately, 25% of biopsies of normal-looking tissue reveal endometriosis, so not all lesions can be viewed and treated.4

Laparoscopic surgery is useful for pain control in mild-to-moderate disease and has been shown to yield a 65% pregnancy rate after 2 years in patients with endometriosis-associated infertility.11 Endometriosis recurs within 2 years after laparoscopy in 40% to 60% of cases, however, and complications occur in 1% to 6% of cases.7

Definitive surgery, which includes hysterectomy and oophorectomy, is reserved for intractable pain or intolerable side effects from medical therapy. Oophorectomy reduces recurrence rates from 62% to 10% and decreases repeat operation rates from 31% to 4%.15 With bilateral oophorectomy, estrogen add-back therapy is required until patients reach a more typical age for menopause. Add-back therapy does not increase recurrence rates (level I evidence). Women should be informed that endometriosis recurs in 5% to 15% of cases even after hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy.6

Case 1 resolution

Jennifer’s history is suggestive of endometriosis. Physical examination revealed localized left-sided pelvic tenderness and decreased uterine mobility. Results of ultrasound scan were normal, with no endometrioma. Initial investigations (urinalysis, Pap smear, and swabs) had normal results. If Jennifer had wanted to conceive, referral to a gynecologist would be warranted. Since this was not the case, continuous COCPs or mefenamic acid could be tried. If these did not control her symptoms, a second-line medical treatment, such as danazol, leuprolide acetate, or possibly the Mirena intra-uterine system, could be tried.

Case 2 resolution

Michelle’s endometriosis was discovered incidentally, and she exhibits no symptoms. Therefore, she does not require any treatment unless symptoms, such as pain or infertility, develop in the future. Unfortunately, no medical therapy has been shown to preserve fertility, and if problems with infertility were to arise in the future, surgical intervention would be necessary.

Endometriosis is a common condition with a range of presenting features and effects. Diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds, and empiric treatment can be offered without diagnostic laparoscopy. Medical and surgical therapies have been shown to be equally effective for symptom relief. Surgical therapy is necessary if pregnancy is desired. If patients are asymptomatic, no treatment is required. Supporting women with endometriosis is an important role for family physicians.

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a common condition with a range of presenting features and effects. Diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds, and empiric treatment can be offered without diagnostic laparoscopy. Medical and surgical therapies have been shown to be equally effective for symptom relief. Surgical therapy is necessary if pregnancy is desired. If patients are asymptomatic, no treatment is required. Supporting women with endometriosis is an important role for family physicians.

Levels of evidence.

Level I: At least one properly conducted randomized controlled trial, systematic review, or meta-analysis

Level II: Other comparison trials, non-randomized, cohort, case-control, or epidemiologic studies, and preferably more than one study

Level III: Expert opinion or consensus statements

Biographies

Dr Jackson, a family physician in Ottawa, Ont, recently completed a fellowship in Women’s Health at the University of Ottawa.

Dr Telner is a family physician at the Toronto East General Hospital and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

References

- 1.Farquhar CM. Extracts from the “clinical evidence.” Endometriosis. BMJ. 2000;320(7247):1449–1452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Child TJ, Tan SL. Endometriosis aetiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Drugs. 2001;61(12):1735–1750. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161120-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farquhar C. Endometriosis. Clin Evidence. 2004;12:2545–2559. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin. Medical management of endometriosis. Number 11, December 1999 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 184, September 1993). Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000;71:183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)80034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Gorp T, Amant F, Neven P, Vergote I, Moeman P. Endometriosis and the development of malignant tumours of the pelvis. A review of literature. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18(2):349–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell B, Colledge E. Educational module: endometriosis. Foundation Med Pract Educ. 2005;13(8):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkel CA. Evaluation and management of women with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(2):397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00474-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes E, Fedorkow D, Collins J, Vandekerckhove P. Ovulation suppression for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. CD000155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kennedy SH, Gavani MR. The investigation and management of endometriosis. London, Engl: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fedele L, Berlanda N. Emerging drugs for endometriosis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2004;9(1):167–177. doi: 10.1517/eoed.9.1.167.32945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valle RF. Endometriosis: current concepts and therapy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78(2):107–119. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahutte MG, Arici A. Medical management of endometriosis-associated pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003;30(1):133–150. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(02)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton CJ, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild, and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62(4):696–700. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Holmes M, Finn P, Garry R. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(4):878–884. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefebvre G, Allaire C, Jeffrey J, Vilos G, Ameja J, Birch C. SOGC clinical guidelines: hysterectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24(1):37–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]