Abstract

Carcinoma in situ (CIS) is the noninvasive precursor of most human testicular germ cell tumors. In normal seminiferous epithelium, specialized tight junctions between Sertoli cells constitute the major component of the blood-testis barrier. Sertoli cells associated with CIS exhibit impaired maturation status, but their functional significance remains unknown. The aim was to determine whether the blood-testis barrier is morphologically and/or functionally altered. We investigated the expression and distribution pattern of the tight junction proteins zonula occludens (ZO) 1 and 2 in normal seminiferous tubules compared to tubules showing CIS. In normal tubules, ZO-1 and ZO-2 immunostaining was observed at the blood-testis barrier region of adjacent Sertoli cells. Within CIS tubules, ZO-1 and ZO-2 immunoreactivity was reduced at the blood-testis barrier region, but spread to stain the Sertoli cell cytoplasm. Western blot analysis confirmed ZO-1 and ZO-2, and their respective mRNA were shown by RT-PCR. Additionally, we assessed the functional integrity of the blood-testis barrier by lanthanum tracer study. Lanthanum permeated tight junctions in CIS tubules, indicating disruption of the blood-testis barrier. In conclusion, Sertoli cells associated with CIS show an altered distribution of ZO-1 and ZO-2 and lose their blood-testis barrier function.

Keywords: Blood-testis barrier, carcinoma in situ, ZO-1, ZO-2, lanthanum tracer

Introduction

Normal spermatogenesis (NSP) depends on functional interactions between somatic Sertoli cells and reproductive germ cells. During puberty, Sertoli cells undergo terminal differentiation, including cessation of cell division, loss of expression of maturation markers, and formation of the blood-testis barrier [1–3]. The blood-testis barrier divides the seminiferous epithelium into a basal compartment and an adluminal compartment. The basal compartment contains spermatogonia and preleptotene spermatocytes, which still have access to circulating blood-borne substances [1,4]. The adluminal compartment contains all other germ cells and is a structurally defined environment created by the secretory and endocytic activities of Sertoli cells. This immune-free environment protects postmeiotic germ cells and is essential for spermatogenesis [5].

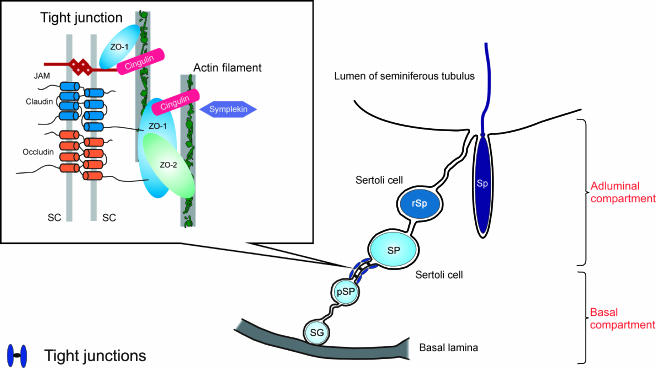

The blood-testis barrier is composed of tight junctions, adherens junctions, and gap junctions. Tight junctions constitute the major structural component of this Sertoli cell junctional complex [1,4]. In general, tight junctions are regions where plasma membranes of adjacent cells form a series of contacts that appear to completely occlude the extracellular space, thereby creating an intercellular barrier and intramembrane diffusion fence [6,7]. The tight junction structure (Figure 1) can be separated basically into two regions of molecules: (1) the transmembrane region, which includes those molecules that mechanically confer adhesiveness to cells by bonding to the same molecule on adjacent cells [8] (these proteins consist of occludin [9], the claudin multigene family [10], and junctional adhesion molecules [11]); and (2) the plaque or peripheral region of the tight junction, which comprises those molecules that anchor transmembrane proteins to the tight junction structure and link them to the cell cytoskeleton and signalling pathways, essentially controlling tight junction structure and function [12–14]. This category comprehends the zonula occludens (ZO) family of MAGUK proteins, consisting of ZO-1 [15], ZO-2 [16], and ZO-3 [17]. Concerning the tight junction proteins of the human blood-testis barrier, only ZO-1 has been positively identified to date [18].

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the current model of the tight junction structure in the seminiferous epithelium. Tight junctions are formed between adjacent Sertoli cells near the basal lamina, constituting the blood-testis barrier and separating the seminiferous epithelium into a basal compartment and an adluminal compartment. SG, spermatogonium; pSP, preleptotene/leptotene spermatocyte; SP, pachytene spermatocyte; rSp, round spermatid; Sp, elongated spermatid; SC, Sertoli cells; JAM, junctional adhesion molecules (modified from Lui et al. [14]).

The 220-kDa protein ZO-1 is likely to constitute the major backbone of the tight junction plaque [19]. ZO-1 is directly linked to actin filaments, anchoring tight junction transmembrane proteins to the actin cytoskeleton [20,21]. Chung et al. [22] demonstrated a significant increase in rat Sertoli cell ZO-1 expression preceding the establishment of tight junctions in vitro. ZO-1 binds directly to occludin [23], claudins [24,25], and junctional adhesion molecules [26]. ZO-1 binding to occludin has been shown to be important in targeting occludin to tight junctions and in anchoring occludin at the extracellular seal [23,27]. Additionally, ZO-1 binds various gap junction proteins, including connexin 43 (Cx43) [28,29], the predominant Cx in Sertoli cells [30]. In mouse Sertoli cells, the colocalization of ZO-1, occludin, and Cx43 to the same junctional complexes was described by Cyr et al. [31], who suggested that cell-cell structural adhesion and communication occur at the same cell-cell interfaces and that ZO-1 may regulate the intracellular assembly of both of these junctions. Direct binding of ZO-2 to Cx43 has been recently reported in cultured normal rat kidney epithelial cells [32].

Testicular carcinoma in situ (CIS) is a noninvasive precursor of testicular germ cell tumors [33], which are the most common type of cancer in young men, exhibiting a rising incidence [34,35]. Testicular cancer progression has been correlated with an impaired status of Sertoli cell differentiation [36–39], which includes downregulation of Cx43 [40]. Functional significance behind the impaired maturation status of Sertoli cells associated with CIS cells remains unknown. Thus, the aim of the present study was to determine whether the blood-testis barrier is morphologically and/or functionally altered. Considering the colocalization of tight junctions and gap junctions at the blood-testis barrier and considering that ZO-1 and ZO-2 are associated with both, we investigated the expression and distribution pattern of these proteins in human seminiferous tubules with NSP compared to tubules showing CIS. Additionally, the functional integrity of the blood-testis barrier in CIS tubules was examined by assessing resistance to penetration using lanthanum nitrate as electron-opaque tracer.

Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemistry

Testicular biopsies, which were taken for diagnostic purposes, were immersed in Bouin's fixative for 24 hours and embedded in paraffin wax using standard techniques. Sections (5 µm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and scored for spermatogenesis. Diagnosis of CIS was confirmed by immunohistochemistry, using a monoclonal antibody to placental alkaline phosphatase, according to the manufacturer's protocol (DAKO, Hamburg, Germany).

After written informed consent had been obtained, immunohistochemistry for ZO-1 and ZO-2 was performed on biopsies from 9 testes of 8 patients (ages 28–47 years; mean = 38.5 years) with NSP (by histology; score 10–9) [41] and from 23 testes of 19 patients (ages 20–47 years; median = 33.9 years) with seminiferous tubules infiltrated with CIS and impaired spermatogenesis (score 7-0) (Table 1). Deparaffinized and rehydrated sections for ZO-1 and ZO-2 immunostaining were microwave-treated at 1000 W in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 to 20 minutes. Sections were blocked with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT), with 3% slim milk powder (Heirler Cenouis, Radolfzell, Germany) in Tris-HCl buffer for 30 minutes at RT, and, finally, with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-HCl buffer for 30 minutes at RT. Afterward, they were incubated overnight with rabbit polyclonal anti-ZO-1 (1:500; Zymed, San Francisco, CA) or goat polyclonal anti-ZO-2 (1:300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) primary antibody in a humid chamber at 4°C. Sections were then exposed for 45 minutes at RT to biotinylated secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG for ZO-1 (1:100; DAKO), and rabbit anti-goat IgG for ZO-2 (1:100; DAKO). Then, sections were treated with a Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA) for 45 minutes at RT. Immunoreaction was visualized using DAB solution (Biologo, Kronshagen, Germany) for 1 to 2 minutes at RT. Following each incubation, sections were washed thoroughly with 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4. Slices were counterstained with hematoxylin for 10 seconds and rinsed with running water. Finally, sections were mounted with Kaiser's glycerol gelatin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Control sections were treated with normal appropriate animal sera or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), omitting the primary antibody, and were negative throughout. For positive control, mouse testes were used. Experiments were repeated thrice.

Table 1.

Histologic Diagnosis after Hematoxylin-Eosin Staining.

| Testicular Biopsy | Patient Age (years) | NSP | CIS + RSP | CIS Only | Score |

| 1 | 39 | x | 10 | ||

| 2 | 39 | x | 10 | ||

| 3 | 39 | x | 10 | ||

| 4 | 28 | x | 10 | ||

| 5 | 39 | x | 10 | ||

| 6 | 47 | x | 9 | ||

| 7 | 38 | x | 10 | ||

| 8 | 44 | x | 10 | ||

| 9 | 34 | x | 10 | ||

| 10 | 47 | x | 5 | ||

| 11 | 32 | x | 7 | ||

| 12 | 32 | x | 5 | ||

| 13 | 29 | x | 4 | ||

| 14 | 29 | x | 5 | ||

| 15 | 37 | x | 6 | ||

| 16 | 27 | x | 4 | ||

| 17 | 41 | x | 5 | ||

| 18 | 40 | x | 3 | ||

| 19 | 41 | x | 6 | ||

| 20 | 37 | x | 0 | ||

| 21 | 37 | x | 0 | ||

| 22 | 31 | x | 0 | ||

| 23 | 26 | x | 0 | ||

| 24 | 26 | x | 0 | ||

| 25 | 35 | x | 0 | ||

| 26 | 20 | x | 0 | ||

| 27 | 36 | x | 0 | ||

| 28 | 29 | x | 0 | ||

| 29 | 31 | x | 0 | ||

| 30 | 42 | x | 0 | ||

| 31 | 35 | x | 0 | ||

| 32 | 29 | x | 0 | ||

| 33 | 49 | x | 10 | ||

| 34 | 35 | x | 10 | ||

| 35 | 52 | x | 10 | ||

| 36 | 37 | x | 10 | ||

| 37 | 64 | x | 10 | ||

| 38 | 40 | x | 10 | ||

| 39 | 38 | x | 9 | ||

| 40 | 44 | x | 10 | ||

| 41 | 39 | x | 3 | ||

| 42 | 38 | x | 4 | ||

| 43 | 41 | x | 5 | ||

| 44 | 47 | x | 5 | ||

| 45 | 42 | x | 3 | ||

| 46 | 35 | x | 4 | ||

| 47 | 35 | x | 10 | ||

| 48 | 37 | x | 10 | ||

| 49 | 37 | x | 5 | ||

| 50 | 36 | x | 6 | ||

| 51 | 43 | x | 4 | ||

| 52 | 30 | x | 6 | ||

| 53 | 47 | x | 3 | ||

| 54 | 34 | x | 5 | ||

| 55 | 40 | x | 7 | ||

| 56 | 38 | x | 0 | ||

| 57 | 37 | x | 0 | ||

| 58 | 43 | x | 0 | ||

| 59 | 46 | x | 0 | ||

| 60 | 35 | x | 0 | ||

| 61 | 49 | x | 0 |

NSP, normal spermatogenesis; RSP, residual spermatogenesis; CIS, carcinoma in situ.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

For Western blot analysis, testicular biopsies of 14 men (ages 35–64 years; mean = 42.9 years) were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further processing. Histologic evaluation of these testes revealed NSP in eight cases and CIS with residual spermatogenesis (RSP) in six cases (Table 1). Protein extraction was carried out using the TRIzol reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany). The same amount of protein was loaded per lane. Proteins for ZO-1 were fractionated on 3–8% Tris-Acetat gel (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) under reducing conditions, using 1x Tris-Acetat SDS Running Buffer (Invitrogen) and the protein marker Dual Color Precision Plus Protein Standards (Bio-Rad, München, Germany). Proteins for ZO-2 were fractionated on 4% to 12% Tris-Bis Gel (Invitrogen) under reducing conditions, using 1x NuPAGE MOPS-SDS Running Buffer (Invitrogen) and the protein marker See Blue Plus 2 (Invitrogen). Then, proteins were blotted (at 30 V for 1 hour; Biometra Standard Power Pack P25; Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen), using 1x NuPAGE Mops-SDS Transfer Buffer (Invitrogen). The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA and 5% nonfat dry milk in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) for 30 minutes at RT and incubated with anti-ZO-1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:500; Zymed) or anti-ZO-2 goat polyclonal antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in PBS with 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany) overnight at RT. After blocking with 5% goat serum in PBS for ZO-1 or with 5% rabbit serum in PBS for ZO-2 for 30 minutes at RT, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG for ZO-1 (1:1000; DAKO) or biotinylated rabbit anti-goat IgG for ZO-2 (1:1000; DAKO) in PBS with 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 was used as secondary antibody (60 minutes, RT). Finally, the membrane was treated with Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector) and developed with True Blue Peroxidase Substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Control Western blot analyses were carried out by omitting the primary antibody and by using normal appropriate animal sera. For positive control, mouse and canine testes were used. Western blot experiments were repeated thrice.

RNA Extraction, DNase Treatment, cDNA Synthesis, and Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) from Tissue Homogenates

For RT-PCR, the same biopsies were used as for Western blot analysis. RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Life Technologies) and then incubated with RNase-free DNase I (1–3 U/µg RNA; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) for 40 minutes at 37°C. Firststrand cDNA synthesis was performed using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Gibco BRL, Eggenstein, Germany). Resulting cDNA sequences were forwarded to PCR. PCR master mix contained 31.75 µl of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-water, 10 µl of 5x PCR buffer (Promega, Heidelberg, Germany), 4 µl of 25 mM MgCl2, 1 µl of 10 mM dNTP (Promega), 1 µl of forward primer (10 pmol), 1 µl of reverse primer (10 pmol), 1 µl of cDNA, and 0.25 µl of Go-Taq-Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega). Primers (Table 2) were purchased from MWG-Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany). Probes were run on a thermocycler (T3; Biometra) under the following conditions: 1x, 95°C, 2 minutes; 29x [95°C, 30 seconds; 55°C, 30 seconds; 72°C, 30 seconds]; 72°C, 7 minutes, resulting in a product of 370 bp for ZO-1; 1x, 95°C, 2 minutes; 34x [95°C, 30 seconds; 54°C, 30 seconds; 72°C, 30 seconds]; 72°C, 7 min, resulting in a product of 306 bp for ZO-2 F1 and 476 bp for ZO-2 F2 (data not shown). Amplicons were separated on a 2% agarose gel and visualized with SYBR-Green (Sigma-Aldrich). All experiments included controls lacking reverse transcriptase enzyme to exclude contamination with genomic DNA or were run with DEPC water instead of RNA to exclude contamination from buffers and tubes. Both controls were negative. Sequencing of PCR products was performed by Qiagen Sequencing Service (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Table 2.

RT-PCR Primer Pairs for Analysis of ZO Molecules.

| Molecule | Primer Sequence | |

| ZO-1 | ZO-1F | 5′-CGG TCC TCT GAG CCT GTA AG-3′ |

| ZO-1R | 5′-GGA TCT ACA TGC GAC GAC AA-3′ | |

| ZO-2 | ZO-2R | 5′-AAC TTC TGC CAT CAA ACT CG-3′ |

| ZO-2F1 | 5′-CCG GAG GCA GAG ACA ACC C-3′ | |

| ZO-2F2 | 5′-CGC CTA CGC GGG ACC TGT G-3′ | |

Lanthanum Nitrate Tracer Study

Biopsies from 15 testes of 15 men (ages 30–49 years; mean = 39.1 years) attending the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf were obtained for diagnostic purposes (Table 1). After written informed consent had been obtained, tissue samples were cut into two blocks. One block was immediately fixed by immersion in 5.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 M cacodylate buffer adjusted to pH 7.35 (at least 3 hours), postfixed in 1% OsO4 (1 hour), dehydrated, and embedded in Epon 812 (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). The second block was processed identically, but fixation solution contained 1% lanthanum nitrate. Semithin sections were stained with toluidine blue, mounted in Eukitt (Riedel-de Haen, Seelze, Germany), and photographed. Thin sections were double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined in Zeiss EM 109 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Histologically, the material was divided into two groups: (1) tubules with NSP (2 testes), and (2) tubules with CIS cells, which are large atypical-appearing germ cells showing characteristic ultrastructural features such as irregular nuclei containing numerous nucleoli and large amounts of glycogen granula [42] (13 testes).

Results

Immunohistochemistry, Western Blot Analysis, and RT-PCR

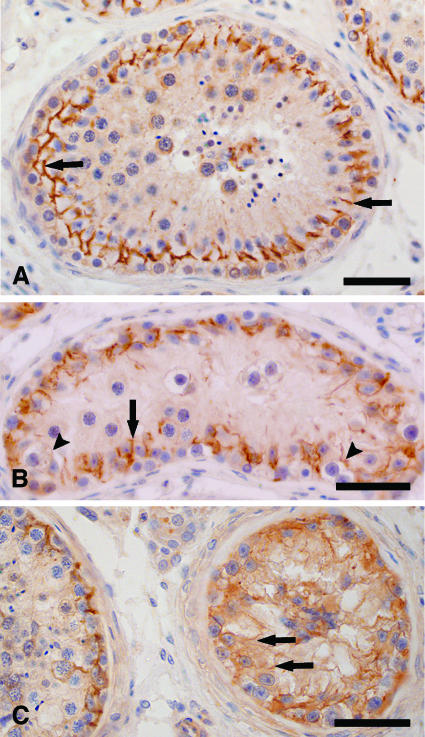

In sections with NSP, ZO-1 (data not shown) and ZO-2 immunostaining was concentrated and precisely colocalized in a linear fashion at the basolateral site of adjacent Sertoli cells, as shown in Figure 2A. Immunoreactive ZO-1 and ZO-2 formed an almost continuous belt at the base of normal seminiferous epithelium. In tubules with CIS cells and RSP, there was progressive loss of ZO-1 and ZO-2 immunostaining from its normal intercellular location at the basolateral site of Sertoli cells, becoming more diffuse and decreasing in intensity (Figure 2B). In tubules that are devoid of normal germ cells in the presence of CIS cells (CIS-only tubules), additional immunoreaction was observed at the lateral site of Sertoli cells up to the adluminal compartment, as well as in their cytoplasm (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical localization of ZO-2 in human seminiferous epithelium. (A) Cross section of a normal seminiferous tubule. Immunoreactive ZO-2 is localized between Sertoli cells at the basal compartment, consistent with the site of the blood-testis barrier (arrows). (B) Cross section of a tubule with CIS cells and RSP. In regions with RSP, ZO-2 immunostaining is concentrated at the basolateral region of Sertoli cells (arrows), whereas in regions containing CIS cells, ZO-2 immunostaining became weak and diffuse (arrowheads). (C) Cross section of a seminiferous tubule containing CIS cells, and cross section of a part of a normal tubule. Within the CIS-only tubule, ZO-2 immunostaining became even weaker and more diffuse around the basolateral site, but spread to stain the lateral site of Sertoli cells up to the adluminal compartment, as well as their cytoplasm (arrows). Bar = 50 µm.

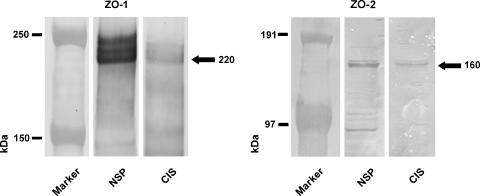

Western blot analysis (Figure 3) revealed ZO-1 immunoreactivity by a triple band between 220 and 240 kDa in testes with NSP and by a weaker triple band at the same level in testes with CIS. ZO-2 immunoreactivity was revealed by a band at approximately 160 kDa in testes with NSP and by a weaker band at the same level in testes with CIS.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis for ZO-1 and ZO-2 of testis homogenates. Western blot analysis revealed ZO-1 immunoreactivity by a triple band between approximately 220 and 240 kDa in testes with NSP and by a weaker triple band at the same level in testes with CIS. ZO-2 immunoreactivity was revealed by a band at approximately 160 kDa in testes with NSP and by a weaker band at the same level in testes with CIS.

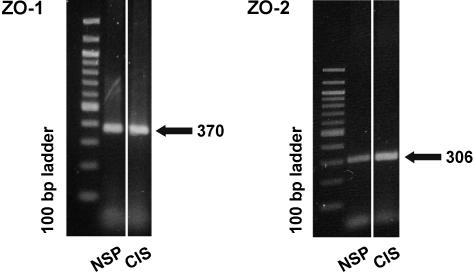

Using RT-PCR (Figure 4), mRNA encoding ZO-1 and ZO-2 were identified in testes with NSP and CIS, detecting specific bands of 370-bp and 306-bp PCR products, respectively. Sequencing of PCR products confirmed the identity of human tight junction proteins ZO-1 and ZO-2 mRNA (NCBI accession no. L14837 for ZO-1 and accession no.NM_201629 for ZO-2].

Figure 4.

RT-PCR analysis for ZO-1 and ZO-2 mRNA of testis homogenates. By RT-PCR, an amplification product of expected size (370 bp for ZO-1 and 306 bp for ZO-2) is obtained in testes with NSP and in testes showing CIS, confirming the presence of ZO-1 and ZO-2 mRNA.

Lanthanum Nitrate Tracer Study

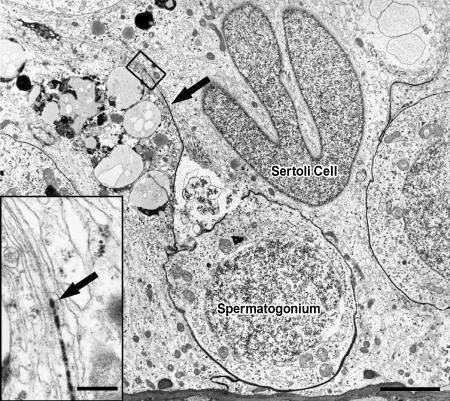

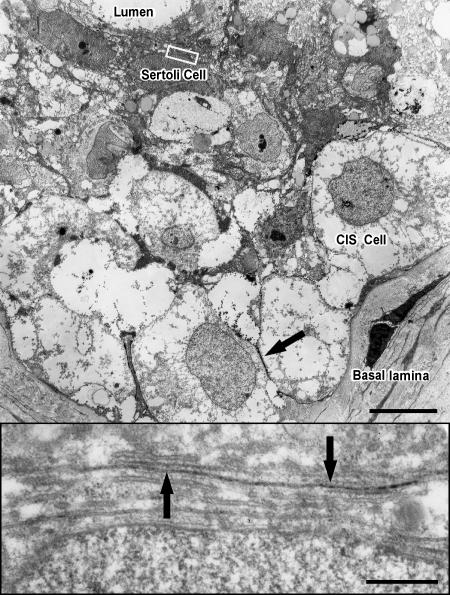

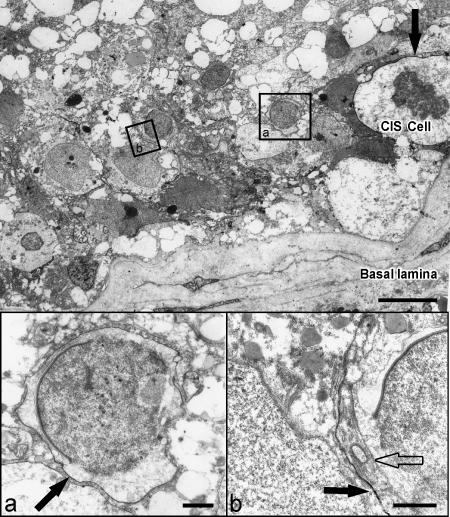

Lanthanum nitrate penetrated the basal lamina to enter seminiferous tubules and subsequently crossed into the intercellular spaces of the seminiferous epithelium. Within the normal seminiferous epithelium, lanthanum was spread evenly between Sertoli cells and early stages of spermatogenesis, but was unable to pass Sertoli cell junctions. Only spermatogonia types A and B were surrounded by the electron-opaque tracer (Figure 5). In tubules containing only CIS cells, lanthanum passed inter-Sertoli cell junction units, identified by typical subsurface bundles of actin filaments and associated endoplasmic reticulum. The tracer was detectable in the adluminal compartment up to the lumen (Figure 6). In tubules with CIS cells and RSP, it could be determined whether germ cells (such as early round spermatids) are impregnated by the tracer, indicating local disruption of the blood-testis barrier (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Electron micrograph of a seminiferous tubule showing NSP. Lanthanum tracer, which appears as an electron-dense material (arrow), impregnates spermatogonia on the basal lamina. Bar = 5 µm. Enlargement of inset: Inter-Sertoli cell junctional complex, where tracer (arrow) penetration is stopped by tight junctions. Bar = 0.5 µm.

Figure 6.

Electron micrograph of a seminiferous tubule containing CIS cells. Lanthanum tracer (arrow) surrounds CIS cells on the basal lamina. Bar = 10 µm. Enlargement of inset: Inter-Sertoli cell junctional complex, typified by subsurface bundles of actin filaments and associated cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum. Lanthanum tracer (arrows) passes through the junctional complex, illustrating that tight junctions were functionally disrupted. Bar = 0.5 µm.

Figure 7.

Electron micrograph of a seminiferous tubule containing CIS cells and RSP. Lanthanum tracer (black arrow) surrounds the CIS cell on the basal lamina and the neighboring round spermatid (inset a), illustrating local disruption of the blood-testis barrier. In the area of residual spermatogenesis, the intercellular space of a round spermatid is free of lanthanum (inset b), indicating an intact blood-testis barrier. Bar = 10 µm. Enlargement of inset a: Round spermatid with lanthanum in the intercellular space (black arrow). Bar = 1 µm. Enlargement of inset b: Round spermatid without lanthanum in the intercellular space (transparent arrow). Black arrow shows lanthanum in the intercellular space of two Sertoli cells. Bar = 1 µm.

Discussion

Sertoli cells associated with CIS cells undergo a process of dedifferentiation, as seen, for example, by the reexpression of cytokeratin 18 intermediate filaments [37]. Cytokeratin 18 intermediate filaments are usually observed in Sertoli cells of fetal testes and indicate a state of undifferentiation [43–45]. Furthermore, Brehm et al. [40] reported the disappearance of Cx43 from Sertoli cells in tubules infiltrated with CIS, which is typically expressed together with terminal differentiation of Sertoli cells during puberty [30]. To determine the functional significance of this impaired maturation status of Sertoli cells, we examined the expression and distribution pattern of the tight junction proteins ZO-1 and ZO-2, as well as the permeability of the blood-testis barrier in tubules containing CIS cells.

Using immunohistochemistry, Western blot analysis, and RT-PCR, we could demonstrate ZO-1 and ZO-2 in the seminiferous epithelium with NSP, as well as with CIS. In normal seminiferous epithelium, ZO-1 and ZO-2 formed continuous belts of strong immunohistochemical staining at the level of the blood-testis barrier. This distribution coincided with the expression of ZO-1 reported in the testes of mice [46], rats [4], guinea pigs [47], and dogs [48], as well as in human testes [18]. The expression of ZO-2 in inter-Sertoli tight junctions has only been described so far in canine testes [49].

Within CIS tubules, ZO-1 and ZO-2 immunoreactivity became weak and diffuse at the blood-testis barrier region but spread to stain the entire lateral site of Sertoli cells, as well as their cytoplasm, indicating altered localization. Similar findings have been reported in breast tissues, where ZO-1 and ZO-2 staining was confined to intercellular regions in normal tissues whereas staining was diffuse and cytosolic in tumor tissues [50]. Glaunsinger et al. [51] have shown that ZO-2 is a cellular target for tumorigenic Ad9 E4-ORF1 and that this interaction results in aberrant sequestration of ZO-2 within the cytoplasm.

Permeability of tight junctions is best assessed using lanthanum nitrate as an electron-opaque tracer given that the number of strands of tight junctions is not a reliable indicator of junctional tightness [52]. As reported in previous studies [1,53–56], lanthanum entered the basal lamina of seminiferous tubules and subsequently penetrated the intercellular spaces of adjacent Sertoli cells and spermatogonia. In tubules with NSP, the tracer was consistently stopped at Sertoli cell junctions of the basal compartment and therefore excluded from the adluminal compartment. In contrast, in sections with CIS, lanthanum passed through tight junction leaflets and entered the adluminal compartment, indicating disruption of the blood-testis barrier. Thus, in the present study, it was demonstrated for the first time that Sertoli cells associated with CIS cells lose their blood-testis barrier function.

The loss of the functional integrity of the blood-testis barrier in CIS tubules reflected by the penetration of lanthanum was consistent with changes in the distribution pattern of ZO-1 and ZO-2. Thus, the dislocation of ZO-1 and ZO-2 from the basolateral region of Sertoli cells may be related to the increased permeability of the blood-testis barrier in CIS tubules. Changes in the distribution pattern of ZO-1 have been related to an increased permeability of tight junctions by a number of previous studies. In MDCK cells, for instance, hepatocyte growth factor caused the redistribution of ZO-1, reducing its association with occludin and moving it away from the site of tight junctions to the cytoplasm, which in turn perturbed the tight junction-permeability barrier [57]. Toxicants such as lindane and CdCl2, which induce disruption of the blood-testis barrier, also delocalize ZO-1 from Sertoli cell membranes to the cytoplasmic compartment [58,59]. Yan and Cheng [60] reported that occludin and ZO-1 appeared to diffuse away from the blood-testis barrier site during Adjudin-induced germ cell depletion. Furthermore, an ATP depletion-repletion model suggested that ZO-1 becomes associated with the cytoskeletal protein fodrin when ATP is depleted from the system. This, in turn, pulls ZO-1 laterally away from sites of tight junctions, inducing tight junction leakiness. On repletion of ATP, the association between ZO-1 and fodrin becomes disrupted, allowing ZO-1 molecules to move back to tight junction sites, resealing tight junctions [61].

Tight junctions are disrupted in a number of tumor types, including stomach, colon, and breast cancers, and are associated with downregulation of ZO-1 and occludin [62,63]. Yoshida et al. [64] noted strong staining for ZO-1 on cell-cell contact in well differentiated and moderately differentiated human gastric adenocarcinoma cell lines. In contrast, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma cells showed a markedly lower ZO-1 staining on cell-cell contact, whereas ZO-1 immunostaining in the cytosol was more abundant. The authors suggest that the localization of ZO-1 on cell-cell contact varies depending on the degree of differentiation of gastric cancer cells.

Changes in the distribution pattern of ZO-1 and ZO-2 and the disruption of the blood-testis barrier are first detectable in tubules containing CIS cells associated with germ cells at the level of primary spermatocytes or even single early round spermatids and are progressive with increasing numbers of CIS cells. These data are in line with previous studies showing that Sertoli cells associated with CIS undergo a process of dedifferentiation indicated by the progressive reexpression of cytokeratin 18 intermediate filaments [37] and loss of Cx43 expression [40,65].

We found ZO-1 and ZO-2 to be associated with the blood-testis barrier region in men with NSP. In the case of ZO-2, this is the first report to show the localization of this tight junction protein in human seminiferous epithelium. The ZO-1 and ZO-2 expression pattern was also demonstrated at different stages of human testicular CIS. Within CIS tubules, ZO-1 and ZO-2 immunoreactivity became weak, diffuse, and cytosolic. Furthermore, we demonstrated the loss of functional integrity of Sertoli cell tight junctions in CIS tubules. The disruption of the blood-testis barrier may be related to the dislocation of ZO-1 and ZO-2 to the Sertoli cell cytoplasm. It can be concluded that the impaired maturation status of Sertoli cells associated with CIS cells includes alterations in the distribution of ZO-1 and ZO-2 and the breakdown of the blood-testis barrier. The distribution pattern and impact of the transmembrane tight junctional proteins occludin and claudins have to be determined.

Acknowledgement

The excellent technical assistance of A. Hild is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- CIS

carcinoma in situ

- Cx

connexin

- RT

room temperature

- ZO

zonula occludens

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Engemann Stiftung (Giessen, Germany).

References

- 1.Dym M, Fawcett DW. The blood-testis barrier in the rat and the physiological compartmentation of the seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1970;3:308–326. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/3.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gondos B, Berndston WE. Postnatal and pubertal development. In: Russel LD, Griswold MD, editors. The Sertoli Cell. Clearwater, FL: Cache River Press; 1993. pp. 115–154. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steger K, Rey R, Louis F, Kliesch S, Behre HM, Nieschlag E, Hoepffner W, Bailey D, Marks A, Bergmann M. Reversion of differentiated phenotype and maturation block in Sertoli cells in pathological human testis. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:136–143. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byers SW, Pelletier R-M. Sertoli cell tight junctions and the blood-testis barrier. In: Cerejido M, editor. Tight Junctions. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griswold MD. Interactions between germ cells and Sertoli cells in the testis. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:211–216. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Nelson WJ. Morphogenesis of the polarized epithelial cell phenotype. Science. 1989;245:718–725. doi: 10.1126/science.2672330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gumbiner BM. Breaking through the tight junction barrier. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1631–1633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitic LL, Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions: I. Tight junction structure and function: lessons from mutant animals and proteins. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G250–G254. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.2.G250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Occludin: a novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1777–1788. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fanning AS, Mitic LL, Anderson JM. Transmembrane proteins in the tight junction barrier. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1337–1345. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1061337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams LA, Martin-Padura I, Dejana E, Hogg N, Simmons DL. Identification and characterisation of human junctional adhesion molecule (JAM) Mol Immunol. 1999;36:1175–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zahraoui A, Louvard D, Galli T. Tight junction, a platform for trafficking and signalling protein complexes. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:31–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.f31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riesen FK, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Wunderli-Allenspach H. A ZO1-GFP fusion protein to study the dynamics of tight junctions in living cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;117:307–315. doi: 10.1007/s00418-002-0398-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lui W-Y, Mruk D, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Sertoli cell tight junction dynamics: their regulation during spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:1087–1097. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.010371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson BR, Siliciano JD, Mooseker MS, Goodenough DA. Identification of ZO-1: a high molecular weight polypeptide associated with the tight junction (zonula occludens) in a variety of epithelia. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:755–766. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.3.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gumbiner B, Lowenkopf T, Apatira D. Identification of a 160 kDa polypeptide that binds to the tight junction protein ZO-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3460–3464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haskins J, Gu L, Wittichen ES, Hibbard J, Stevenson BR. ZO-3, a novel member of the MAGUK protein family found at the tight junction, interacts with ZO-1 and occludin. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:199–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moroi S, Saitou M, Fujimoto K, Sakakibara A, Furuse M, Yoshida O, Tsukita S. Occludin is concentrated at tight junctions of mouse/rat but not human/guinea pig Sertoli cells in testes. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1708–C1717. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itho M. Structural and signalling molecules come together at tight junctions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:628–633. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fanning AS, Jameson BJ, Jesaitis LA, Anderson JM. The tight junction protein ZO-1 establishes a link between the transmembrane protein occludin and the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29745–29753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wittchen ES, Haskins J, Stevenson BR. Protein interactions at the tight junction. Actin has multiple binding partners, and ZO-1 forms independent complexes with ZO-2 and ZO-3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35179–35185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung SSW, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Study of the formation of specialized inter-Sertoli cell junctions in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:258–272. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199911)181:2<258::AID-JCP8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuse M, Itoh M, Hirase T, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Direct association of occludin with ZO-1 and its possible involvement in the localization of occludin at tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1617–1626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin-1 and -2: novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1539–1550. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh M, Furuse M, Morita K, Kubota K, Saitou M, Tsukita S. Direct binding of three tight junction-associated MAGUKs, ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3, with the COOH termini of claudins. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1351–1363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Citi S, Volberg T, Bershadsky AD, Denisenko N, Geiger B. Cytoskeletal involvement in the modulation of cell-cell junctions by the protein kinase inhibitor H-7. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:683–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fallon MB, Brecher AR, Balda MS, Matter K, Anderson JM. Altered hepatic localization and expression of occludin after common bile duct ligation. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C1057–C1062. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.4.C1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giepmans BN, Moolenaar WH. The gap junction protein connexin43 interacts with the second PDZ domain of the zona occludens-1 protein. Curr Biol. 1998;8:931–934. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toyofuku T, Yabuki M, Otsu K, Kuzuya T, Hori M, Tada M. Direct association of the gap junction protein connexin43 with ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12725–12731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steger K, Tetens F, Bergmann M. Expression of connexin 43 in human testis. Histochem Cell Biol. 1999;112:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s004180050409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cyr DG, Hermo L, Egenberger N, Mertineit C, Trasler JM, Laird DW. Cellular immunolocalization of occludin during embryonic and postnatal development of the mouse testis and epididymis. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3815–3825. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh D, Solan JL, Taffet SM, Javier R, Lampe PD. Connexin 43 interacts with zona occludens-1 and -2 proteins in a cell cycle stage-specific manner. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30416–30421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506799200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skakkebaek NE. Possible carcinoma-in-situ of the testis. Lancet. 1972;2:516–517. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)91909-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergstrom R, Adami HO, Mohner M, Zatonski W, Storm H, Ekbom A, Tretli S, Teppo L, Akre O, Hakulinen T. Increase in testicular cancer incidence in six European countries: a birth cohort phenomenon. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:727–733. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.11.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bray F, Richiardi L, Ekbom A, Pukkala E, Cuninkova M, Moller H. Trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality in 22 European countries: continuing increases in incidence and declines in mortality. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3099–3111. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebaek NE. The possible role of sex hormones in the development of testicular cancer. Eur Urol. 1993;23:54–59. doi: 10.1159/000474570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kliesch S, Behre HM, Hertle L, Bergmann M. Alteration of Sertoli cell differentiation in the presence of carcinoma-in-situ in human testis. J Urol. 1998;160:1894–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Jorgensen N, Carlsen E, Petersen PM, Giwercman A, Andersen AG, Jensen TK, Anderson AM, Müller J. Germ cell cancer and disorders of spermatogenesis: an environmental connection? APMIS. 1998;106:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharpe RM, McKinnell C, Kivilin C, Fisher JS. Proliferation and functional maturation of Sertoli cells, and their relevance to disorders of testis function in adulthood. Reproduction. 2003;125:769–784. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brehm R, Marks A, Rey R, Kliesch S, Bergmann M, Steger K. Altered expression of connexins 26 and 43 in Sertoli cells in seminiferous tubules infiltrated with carcinoma-in-situ or seminoma. J Pathol. 2002;197:647–653. doi: 10.1002/path.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bergmann M. Evaluation of testicular biopsy samples from the clinical perspective. In: Schill W-B, Comhaire FH, Hargreave TB, editors. Andrology for the Clinician. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 2006. pp. 454–461. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holstein AF, Roosen-Runge EC, Schirren C. Illustrated Pathology of Human Spermatogenesis. Berlin, Germany: Grosse Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soosay GN, Bobrow L, Happerfield L, Parkinson MC. Morphology and immunohistochemistry of carcinoma-in-situ adjacent to testicular germ cell tumours in adults and children: implications for histogenesis. Histopathology. 1991;19:537–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb01502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogatsch H, Jezek D, Hittmair A, Mikuz G, Feichtinger H. Expression of vimentin, cytokeratin, and desmin in Sertoli cells of human fetal, cryptorchid, and tumor-adjacent testicular tissue. Virchows Arch. 1996;427:497–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00199510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franke FE, Pauls K, Rey R, Marks A, Bergmann M, Steger K. Differentiation markers of Sertoli cells and germ cells in fetal and early postnatal human testis. Anat Embryol. 2004;209:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s00429-004-0434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byers SW, Graham R, Dai HN, Hoxter B. Development of Sertoli cell junctional specializations and the distribution of the tight-junction-associated protein ZO-1 in the mouse testis. Am J Anat. 1991;191:35–47. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001910104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pelletier RM, Okawara Y, Vitale ML, Anderson JM. Differential distribution of the tight-junction-associated protein ZO-1 isoforms α(+) and α(-) in guinea pig Sertoli cells: a possible association with F-actin and γ-actin. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:367–376. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gye MC. Expression of occludin in canine testis and epididymis. Reprod Domest Anim. 2004;39:43–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0531.2003.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jesaitis LA, Goodenough DA. Molecular characterization and tissue distribution of ZO-2, a tight junction protein homologous to ZO-1 and the Drosophila discs—large tumor suppressor protein. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:949–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin TA, Watkins G, Mansel RE, Jiang WG. Loss of tight junction plaque molecules in breast cancer tissues is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2717–2725. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glaunsinger BA, Weiss RS, Lee SS, Javier R. Link of the unique oncogenic properties of adenovirus type 9 E4-ORF1 to a select interaction with the candidate tumor suppressor protein ZO-2. EMBO J. 2001;20:5578–5586. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pelletier RM, Byers SW. The blood-testis barrier and Sertoli cell junctions: structural considerations. Microsc Res Tech. 1992;20:3–33. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connel CJ. A freeze-fracture and lanthanum tracer study of the complex junction between Sertoli cells of the canine testis. J Cell Biol. 1978;76:57–75. doi: 10.1083/jcb.76.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furuya S, Kumamoto Y, Sugiyama S. Fine structure and development of Sertoli junctions in human testis. Arch Androl. 1978;1:211–219. doi: 10.3109/01485017808988339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergmann M, Nashan D, Nieschlag E. Pattern of compartmentation in human seminiferous tubules showing dislocation of spermatogonia. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;256:183–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00224733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cambrosio Mann M, Friess AE, Stoffel MH. Blood-tissue barriers in the male reproductive tract of the dog: a morphological study using lanthanum nitrate as an electron-opaque tracer. Cells Tissues Organs. 2003;174:162–169. doi: 10.1159/000072719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grisendi S, Arpin M, Crepaldi T. Effect of hepatocyte growth factor on assembly of zonula occludens-1 protein at the plasma membrane. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176:465–471. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199809)176:3<465::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fiorini C, Tilloy-Ellul A, Chevalier S, Charuel C, Pointis G. Sertoli cell junctional proteins as early targets for different classes of reproductive toxicants. Reprod Toxicol. 2004;18:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong C, Mruk DD, Lui W, Cheng CY. Regulation of blood-testis barrier dynamics: an in vivo study. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:783–798. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan HH, Cheng CY. Blood-testis barrier dynamics are regulated by an engagement/disengagement mechanism between tight and adherens junctions via peripheral adaptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11722–11727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503855102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsukamoto T, Nigam SK. Tight junction proteins form large complexes and associate with the cytoskeleton in an ATP depletion model for reversible junction assembly. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16133–16139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kimura Y, Shiozaki H, Hirao M, Maeno Y, Doki Y, Inoue M, Monden T, Ando-Akatsuka Y, Furus M, Tsukita S, et al. Expression of occludin, tight-junction-associated protein, in human digestive tract. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:45–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoover KB, Liao SY, Bryant PJ. Loss of the tight junction MAGUK ZO-1 in breast cancer: relationship to glandular differentiation and loss of heterozygosity. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1767–1773. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65691-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshida K, Kanaoka S, Takai T, Uezato T, Miura N, Kajimura M, Hishida A. EGF rapidly translocates tight junction proteins from the cytoplasm to the cell-cell contact via protein kinase C activation in TMK-1 gastric cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;309:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brehm R, Rüttinger C, Fischer P, Gashaw I, Winterhager E, Kliesch S, Bohle RM, Steger K, Bergmann M. Transition from preinvasive carcinoma in situ to seminoma is accompanied by a reduction of connexin 43 expression in Sertoli cells and germ cells. Neoplasia. 2006;8:499–509. doi: 10.1593/neo.05847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]