Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To explore and describe family physicians’ personal and professional responses to performance assessment feedback.

DESIGN

Qualitative study using one-on-one semistructured interviews after feedback on performance.

SETTING

Fee-for-service family practices in eastern Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Eight physicians out of 25 physicians in the control group of a previous randomized controlled trial who received performance assessment feedback were purposefully selected using maximum variation sampling to represent various levels of performance. Five female physicians (2 part-time and 3 full-time) and 3 male physicians (all full-time) were interviewed. These physicians had practised family medicine for an average of 18.5 years (range 9 to 32 years).

METHOD

Semistructured one-on-one interviews were conducted to determine what physicians thought and felt about their private feedback sessions and to solicit their opinions on performance assessment in general. Information was analyzed using an open coding style and a constant comparative method of analysis.

MAIN FINDINGS

Two major findings were central to the core elements of medical professionalism and perceived accountability. Physicians indicated that the private feedback they received was a valuable and necessary part of medical professionalism; however, they were reluctant to share this feedback with patients. Physicians described various layers of accountability from the most important inner layer, patients, to the least important outer layer, those funding the system.

CONCLUSION

Performance feedback was viewed as important to family physicians for maintaining medical professionalism and accountability.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer et décrire les réactions personnelles et professionnelles des médecins de famille aux séances de rétroaction sur l’évaluation de leur compétence.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Étude qualitative à l’aide d’entrevues individuelles semi-structurées postérieures à la rétroaction sur leur performance.

CONTEXTE

Cliniques de médecins de famille rémunérés à l’acte de l’est de l’Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Huit des 25 médecins du groupe témoin d’un essai randomisé antérieur qui avaient eu une séance de rétroaction sur l’évaluation de leur compétence ont été intentionnellement choisis pour obtenir un échantillon le plus varié possible représentant divers niveaux de performance. Cinq médecins féminins (2 à temps partiel et 3 à plein temps) et 3 médecins masculins (tous à plein temps) ont été interviewés. Ces médecins avaient en moyenne 18,5 années de pratique en médecine familiale (entre 9 et 32 ans).

MÉTHODE

On a fait des entrevues individuelles semi-structurées pour déterminer ce que les médecins pensent et ressentent à propos de leur session privée de rétroaction et pour connaître leur opinion sur l’évaluation de leur compétence en général. Les données obtenues ont été analysées selon un mode de codage ouvert et par une méthode d’analyse par comparaison continue.

PRINCIPALES OBSERVATIONS

Deux observations importantes correspondaient à des éléments centraux du professionnalisme médical et de la responsabilité telle que perçue par les médecins. Les participants déclaraient que la rétroaction privée qu’ils avaient reçue constituait un élément valable et nécessaire du professionnalisme médical; ils hésitaient toutefois à partager cette information avec les patients. Les médecins décrivaient différents niveaux de responsabilité, le niveau interne le plus important représenté par les patients et le niveau externe le moins important représenté par ceux qui assurent le financement du système.

CONCLUSION

On estimait que la rétroaction sur la compétence est importante pour maintenir un bon niveau de professionnalisme médical et de responsabilité chez les médecins de famille.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

There is increasing interest in assessment of physicians’ performance, but little is known about how Canadian family physicians perceive and react to such feedback.

This study provides new information about what physicians think and feel regarding feedback on performance assessment and how they link their experience to concepts of medical professionalism and perceived accountability.

Physicians welcomed feedback and saw it as an essential part of medical professionalism; however, they were reluctant to share this information with their patients despite the fact that they felt most accountable to them.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

L’évaluation de la compétence médicale suscite de plus en plus d’intérêt, mais on ne sait pas bien ce que les médecins de famille canadiens pensent des séances de rétroaction ni comment ils y réagissent.

Cette étude apporte un éclairage nouveau sur ce que les médecins de famille pensent de la rétroaction en rapport avec l’évaluation de leur compétence, comment ils y réagissent et de quelle façon ils relient cette expérience aux concepts du professionnalisme médical et de la responsabilité perçue.

Les médecins accueillaient favorablement cette rétroaction et y voyaient un élément essentiel du professionnalisme médical; ils hésitaient toutefois à partager cette information avec leurs patients mêmes s’il estimaient avoir beaucoup de responsabilité envers eux.

There is increasing interest in assessing physicians’ performance both nationally1-4 and around the world.5-9 Assessments have been defined as “the quantitative assessment of physician performance based on the rates at which their patients experience certain outcomes of care and/or the rates at which physicians adhere to evidence-based processes of care during their actual practice of medicine.”10 Evidence suggests that feedback on performance is but one of many interventions used to help improve patient care. Its effectiveness is linked to a host of factors, such as motivation of recipients, timing, frequency, and type of feedback.11 The literature suggests that multifaceted interventions targeting various barriers to optimal performance are generally more effective than single interventions.12-14

According to Parkerton et al,5 the recent re-emergence of physician performance assessments is due in part to public demand for medical accountability. Revalidation is a relatively new concept that is gaining attention as a means for governments, regulators, and others to assure the public that family physicians are maintaining their competence to practise in the years following initial licensure.15,16 Little is known, however, about how Canadian family physicians perceive and react to feedback from assessments.

Using a qualitative design, we sought to discover physicians’ thoughts and feelings about receiving feedback on how well they conducted preventive maneuvers for their patients. We also wanted their opinions on performance assessment in general, and in particular, their thoughts about accountability. Rather than looking at the effectiveness of feedback in changing physicians’ behaviour, this study aimed to provide new information about what physicians think and feel regarding performance assessment feedback and how they link their experience to concepts of medical professionalism and perceived accountability.

METHOD

Qualitative approach

We used a qualitative approach17,18 to collect and analyze data that might help us understand physicians’ thoughts and feelings regarding performance assessment at a personal and a more general level. Due to the confidential nature of the information solicited, we conducted one-on-one semistructured interviews to obtain in-depth personal accounts of physicians’ reactions to performance assessments. Ethics approval was granted by the Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Setting

This study was conducted following a randomized controlled trial of 54 (out of 856) fee-for-service family physicians in eastern Ontario with the goal of increasing appropriate screening behaviour, such as smoking cessation counseling, and decreasing inappropriate screening, such as for prostate-specific antigen. The trial used 54 prevention guidelines produced by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care as criterion standard benchmarks against which to measure physicians’ performance.

Once the study ended, the 27 control practices were offered the opportunity to receive feedback on their individual performance based on the 30 charts audited and on responses to the 90 mailed patient surveys. Feedback consisted of a 20-minute PowerPoint bar graph presentation to convey information on performance on 8 chart-audited maneuvers and 8 maneuvers captured on the patient questionnaire. Scores on each of the maneuvers were compared with the mean scores of the 54 practices before the survey. In addition, a scatter plot graph showed the overall score of each practice relative to the scores of the other 53 practices. Although no ongoing intervention was offered to the control group following the feedback presentation, there was time to discuss the results and to share reminder tools for improving preventive practices. Eighteen of the 27 control practices requested feedback sessions.

The interview guide was pilot-tested. Dr Rowan conducted the interviews, coded the information, and interpreted the findings. She worked with an independent researcher to verify the coding of information. Dr Rowan had not been part of the research team that conducted the main randomized controlled trial. This fact was shared with respondents to enhance their perception of confidentiality and to increase the likelihood of their being open and candid in their discussions.

Sampling method

Purposeful maximum variation sampling18 was used to recruit participants with various levels of performance. Information gathered during one-on-one interviews captured and refined major themes from participants. Audit results indicated they had varying rates of preventive service delivery. Common patterns that emerged from such a diverse group of physicians were of particular interest in helping understand the range of perceptions while capturing core experiences and shared reactions to performance assessment.

Of 43 eligible physicians in the control group of the original study, 25 agreed to receive performance feedback. Nine physicians were interviewed. One subsequently withdrew consent for personal reasons. Theme saturation was reached on priority items after the sixth interview, meaning there was overlap in patterns and themes emerging from items deemed important, such as perceived accountability. Data from the remaining 2 interviews helped to confirm initial patterns. Physicians interviewed included 5 women (2 part-time and 3 full-time) and 3 men (all full-time) who had worked as family physicians for an average of 18.5 years (range 9 to 32 years). All were in fee-for-service solo practices in or near the Ottawa region.

Methods of collecting and analyzing information

Physicians were approached about participating in the study by the nurse facilitator. Nine who expressed interest were contacted to arrange interview times. Interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes and took place at physicians’ offices between November 2003 and January 2004. Most interviews took place within 1 to 2 weeks after feedback was received. Information was audiotaped and transcribed by another researcher, reviewed by the interviewer, and sent to each physician interviewed for verification. Minor revisions were made.

Interviews were semistructured and based on 18 questions. When necessary, respondents were probed further to obtain rich and detailed accounts of their experiences. Most probing questions were determined in advance, but the interviewer could use other probing questions to explore new areas that emerged during interviews.

To enhance the trustworthiness of the data, responses were checked by recycling information back to respondents for verification, data were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim, disconfirming evidence was consciously sought, and full descriptions of respondents’ thoughts and feelings were provided through quotations and examples to confirm theories and patterns. Standardized codes were developed and used to analyze the information. Quantitative data (rank-ordered) were used to condense some results to make them more easily understandable.19

A constant comparative method of analysis was used wherein categories were not rigidly fixed in advance of data gathering but emerged from the interviews. To analyze the data, we used an open coding style.20 The lead author reviewed the transcripts and noted words or phrases that stood out as potentially important. In vivo codes20 were used as much as possible to label categories using respondents’ words or phrases. The coding process was iterative in that the information was reviewed several times before being assigned a final label. Words and phrases were developed into categories or themes. Theories or models were built from this information and from the notes21 taken after each interview. A different reviewer examined the coding; inconsistencies were resolved by consensus.

FINDINGS

Personal reactions to private performance feedback

Feelings during the feedback session.

Most respondents indicated a blend of positive feelings and concern. Most expressed their positive feelings in terms of feeling good, fine, or okay. One physician said, “I thought I was doing a good job before and as a physician we always worry. I felt okay, I am doing okay.” Another said, “I felt that it was good to know those things.” Several respondents said they felt comfortable or not uncomfortable and mentioned they did not feel threatened: “[The facilitator] was not threatening. It was not a threatening situation. She put the facts on the table. [I] was not threatened.”

Feelings of concern most often involved being surprised or puzzled by elements of the feedback. “I was surprised with some of them, particularly the flu shot because I thought we were doing quite well,... but according to the results, over 25% of the people that should be getting it didn’t. I was a little bit surprised at that.”

The strongest concern was expressed by one respondent who felt “under the gun” when areas to be improved were discussed. “I know the study was not intended to look at individuals, overall, but I thought that I was being tested on my delivery of health services. I guess a couple of times I felt I had to be on the defensive.”

Thoughts about the feedback.

All respondents had positive comments about the feedback sessions. Half the respondents provided specific comments. Most often they suggested that feedback provided a valuable norm against which they could evaluate their performance.

I thought it was very useful. I was also surprised that in some ways I was very similar to other people and in other ways I was very different from other people in how things projected. That was fine, it didn’t bother me either way. My report was fairly positive, so that didn’t make me feel too bad. But I wonder how I would have felt if it was terrible. I was curious about that. But I thought it was interesting, and I thought the points that were brought up to me were very valid. I have already tried to change some of the things that were suggested.

Feelings about patients being informed of the feedback they received.

When asked how they would feel if patients were informed about the results of feedback sessions, only 1 respondent indicated without hesitation that it would be all right. Half the respondents were apprehensive about sharing the information with their patients.

Even if [my scores] were really good, I don’t think I would feel comfortable with that because it is a little snapshot of just a small area of what you do…. I think it’d make me feel on guard kind of thing…. [That] would be very anxious and stressful. I would probably hate my profession. I wouldn’t feel very relaxed when I am interacting with the patients. I would be really time strained as well because I would be constantly thinking [about] this issue.

Opinions about performance assessment at a system level

Perceived accountability.

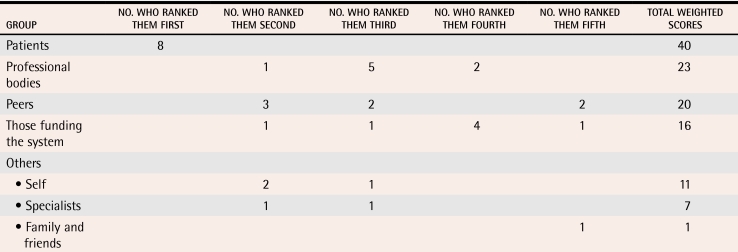

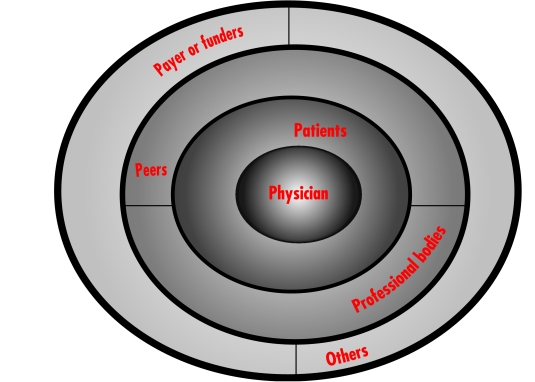

Respondents were asked to rank 5 different groups by their perceived level of accountability to these groups, give a rationale for their ranking, and describe the role of each group in performance assessment (Table 1). Figure 1 shows a model of perceived accountability to various groups. Total weighted scores were calculated by multiplying the number of ranked scores within each cell by the weight indicated in the key and then adding the total for each group. Results suggested that physicians perceive themselves most accountable to patients; and then to professional bodies and peers; and finally to those paying for and funding the system and others, including those identified by respondents as self, specialists, and family and friends.

Table 1. Weighted and ranked accountability scores.

Top ranked—5 points, second rank—4 points, third rank—3 points, fourth rank—2 points, and fifth rank—1 point.

Figure 1.

Model of physician-perceived accountability

Considering the polar ends of this model, patients were perceived to have a formal role in performance assessment that included and also went beyond measuring satisfaction.

It is always good to see feedback and to see studies on what they learned or what they take home when they walk out of the office. So I think [it’s important] to get feedback from them as to their comprehension of their medical issue of what you said or their follow-up with instructions or how they are doing things.…

In contrast, those funding the system were seen as having a limited role in performance assessment. Half the respondents indicated that funders had a responsibility to review or find inappropriate physician practices or “cheaters.”

It is quite reasonable if my profile suggests that my sort of practice pattern or billing pattern or ordering pattern seems inappropriate. I think it is perfectly reasonable that somebody should look at that. I don’t have any trouble with that.

Association between physician performance assessment and various terms and concepts.

During the interview, respondents were asked to describe the association between physician performance assessment and such concepts as medical professionalism, government responsibility, patient choice, and public information. Most respondents viewed physician performance assessment and medical professionalism as related terms in that performance assessment was an integral part of the medical profession.

If you are a medical professional, I think it is part of your life that people are going to assess what you do…. To be a professional, that is something that you have to accept…. I don’t think that it’s something that you should be afraid of or take as a bad thing. I think it is a good thing.

Performance assessment was most often seen as a way to meet professional standards of care. ”To keep some standards. To make you take the time to think about what you are doing and if you are doing well. What you can do better, what you are doing wrong. I think feedback can certainly help professionalism.”

Many respondents viewed the association between performance assessment and government responsibility as problematic or they had mixed feelings about it. Several indicated that the government’s agenda conflicts with patient care and demands.

People are very demanding, and the question really is what the government wants you to do and what the patient wants you to do, and then you have another problem in your hands. You are being squeezed again between two conflicting [priorities]; this is what bothers me.

Most saw government as having a limited or indirect role in physician performance assessment; several respondents linked governments to funding and remuneration as opposed to evaluation of physicians. One participant said, “I think their responsibility is to see that there is adequate funding for what we are trying to do. So it mostly comes down to dollars and cents when you are talking about government.”

While no clear association emerged between physician performance assessment and patient choice, most respondents agreed that patient choice is diminishing, limited, or absent. Most indicated that lack of choice was due to the shortage of doctors and patients’ inability to change doctors.

I think in terms of the physicians, patients have no choice, certainly not here. If you are unhappy with your physician or you are unhappy with what your physician is doing for you, it is very difficult to move along because there are no doctors.

Although half the respondents acknowledged that public information can work positively, particularly for patients, all respondents indicated that public information can also work negatively. They were greatly concerned that patients could misconstrue, misinterpret, or not have enough medical knowledge to assess published information on physicians’ performance.

[Big breath out] That is really a tough question… . If I saw a surgeon’s mortality was such and such, that would not concern me in those terms as much as perhaps someone in the public would be. I don’t think the public would understand that as well as the medical professional would. I think that there is quite a difference there. I think there is a danger. It would be doctors that are thought poorly of because some of the statistics that could be published in the public. I am not in big favour of doing this kind of thing. There could be a lot of misconceptions. I don’t think they understand what goes on and could interpret some of those statistics. I am kind of reluctant to push for anything like that.

DISCUSSION

Two major themes arise from this study and centre around the core elements of medical professionalism and perceived accountability. First, physicians in this study welcomed feedback and saw it as an essential part of medical professionalism. They were reluctant to share this information with their patients, however, despite the fact that they feel most accountable to them. This apparent contradiction needs more exploration. Patients’ trust in their physicians has been proposed as a key feature of patient-physician relationships and linked to increased satisfaction, adherence to treatment, and continuity of care.22 It is important that revealing performance feedback to patients not undermine their trust or negatively affect physicians’ confidence in their role as healers.

The views of the American Medical Association (AMA) are in line with this thinking. It discusses reasons for not sharing results of performance assessments and indicates that “professional accountability and commitment have greater power than does external accountability driven by regulators or payers.”6 The AMA cautions against using performance data to compare physicians or for choosing among physicians because of factors outside the control and influence of these physicians, such as differences among patients who require stratification or risk adjustment. Landon et al10 also noted the importance of adjusting for confounding patient factors that could negatively affect performance outcomes.

The second major finding concerns the layers of accountability described by physicians, from the most important inner layer, patients, to the least important outer layer, those who fund the system, and the implications for performance assessment. Melnick et al23 suggest a need to tailor performance assessment to target the expectations of various audiences. For example, when it is used to measure accountability to patients or to satisfy trust in patient-physician relationships, an assessment should reflect at least in part patients’ expectations regarding what physicians should know and the care they should provide. Alternatively, if the audience is professional bodies and if outcomes of the assessment could lead to certification or recertification, then assessment should focus on areas acceptable to the discipline as defined by the medical profession itself. Alberta’s Physician Achievement Review1 in fact uses physicians themselves, patients, medical peers and colleagues, consulting physicians to whom patients have been referred, and nonphysician co-workers as assessors. This suggests that there are many people to whom physicians are accountable and that they reflect the various functions of physicians in modern medical practice.

Exworthy et al24 studied the location of performance assessment in general practice in the United Kingdom and outlined a hierarchy for physician assessors based on perceived proximity to those being assessed. The hierarchy included general practitioners themselves (GPs), fellow GPs within the practice, fellow GPs within the Primary Care Group (PCG), superordinate GPs within the PCG (eg, chair of clinical governance committee); academic doctors and “experts,” other National Health Service practitioners and the Royal College, and finally government “assessors” or “inspectors.” The further the assessor was perceived to be from the GP assessed, the less likely the GP would be to identify with the assessor and, therefore, the less appropriate the assessor was perceived to be. Physicians in our study also perceived government funders as the furthest removed from them and argued against government bodies having a direct role in performance assessment.

Limitations

The generalizability of this study is limited by the fact that participants volunteered to be assessed and to be part of this follow-up study. We could presume these physicians are more open to improving their practice and possibly feel more positive toward performance assessment than those who did not volunteer. The study focused only on attitudes toward performance assessment in a self-regulating context involving fee-for-service physicians. Differences might be seen in other contexts where physicians work, such as in industrial or bureaucratic settings. Also, measuring performance of preventive services alone does not capture the full spectrum of primary health care services. Opinions might have been different had a more comprehensive assessment been conducted.

Conclusion

Performance feedback was viewed as important to family physicians for maintaining medical professionalism and accountability. This study points to the importance of examining existing physician accountability structures while responding to increasing expectations of public accountability. Decision makers, including governments, colleges, and professional bodies, might do best to direct their efforts toward understanding and working with grass-roots accountability models. They should consider how new “performance” policies will affect existing models of accountability and the nature of trust. Professionalism could well be a strong force that adds value to modern bureaucratic systems.

Further research should examine the most appropriate processes for assessments and how the information gleaned from assessments will be used, including how the results of performance assessments could affect patient-physician relationships and trust. Future studies could focus on surveying family physicians in Ontario to assess their attitudes toward various performance assessment processes, including the Peer Assessment Program run by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. How would they like performance assessments done? By whom? Using what indices? And for what purposes?

Biographies

Dr Rowan teaches in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Ottawa in Ontario and is a researcher in the C.T. Lamont Centre at the Élisabeth Bruyère Research Institute.

Dr Hogg teaches in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Ottawa and is a researcher at the C.T. Lamont Centre and the Institute of Population Health.

Dr Martin teaches in the Northern Ontario School of Medicine and is a researcher in the Indigenous Peoples’ Health Research Centre at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon.

Ms Vilis is an outreach facilitator coordinator involved in research at the University of Ottawa.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Hall W, Violato C, Lewkonia R, Lockyer J, Fidler H, Toews JJ, et al. Assessment of physician performance in Alberta: the Physician Achievement Review. CMAJ. 1999;161:52–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazandjian VA. Power to the people: taking the assessment of physician performance outside the profession. CMAJ. 1999;161:44–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norton PG, Dunn EV, Beckett R, Faulkner D. Long-term follow-up in the Peer Assessment Program for nonspecialist physicians in Ontario, Canada. J Qual Improv. 1998;24(6):334–341. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page GG, Bates J, Dyer SM, Vincent DR, Bordage G, Jacques A, et al. Physician-assessment and physician-enhancement programs in Canada. CMAJ. 1995;153:1723–1728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkerton PH, Smith DG, Belin TR, Feldbau GA. Physician performance assessment: nonequivalence of primary care measures. Med Care. 2003;41(9):1034–1047. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000083745.83803.D6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kmetik K, Williams J, Hammons T, Rosof B. The American Medical Association and physician performance measurement: information for improving patient care. Tex Med. 2000;96(10):80–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norcini JJ. Recertification in the United States. BMJ. 1999;319:1183–1185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7218.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Southgate L, Pringle M. Revalidation in the United Kingdom: general principles based on experience in general practice. BMJ. 1999;319:1180–1183. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7218.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newble DI, Paget NS. The maintenance of professional standards programme of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1996;30:252–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landon B, Normand S-LT, Blumenthal D, Daley J. Physician clinical performance assessment: prospects and barriers. JAMA. 2003;290(9):1183–1189. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Weijden T, Grol R. Feedback and reminders. In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, editors. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Limited; 2005. pp. 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wensing M, Grol R. Multifaceted interventions. In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, editors. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Limited; 2005. pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):112–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wensing M, van der Weijden T, Grol R. Implementing guidelines and innovations in general practice: which interventions are effective? Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(427):991–997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondro W. Lifelong medical licenses may end in 5 years [comment]. CMAJ. 2004;171:317. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKinley RK, Fraser RC, Baker R. Model for directly assessing and improving clinical competence and performance in revalidation of clinicians. BMJ. 2001;322:712–715. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Beverly Hills, Calif: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mays N, Pope C. Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ. 1995;311:109–112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6997.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basis of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charmaz K. Grounded theory: objectives and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 509–535. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanford Trust Study Physicians of Palo Alto, California. Thom DH. Physician behaviors that predict patient trust. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melnick DE, Asch DA, Blackmore DE, Klass DF, Norcini FF. Conceptual challenges in tailoring physician performance assessment to individual practice. Med Educ. 2002;36:931–935. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Exworthy M, Wilkinson EK, McColl A, Moore M, Roderick P, Smith H, et al. The role of performance indicators in changing the autonomy of the general practice profession in the UK. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1493–1504. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]