Abstract

The 26S proteasome consists of the 20S proteasome (core particle) and the 19S regulatory particle made of the base and lid substructures, and it is mainly localized in the nucleus in yeast. To examine how and where this huge enzyme complex is assembled, we performed biochemical and microscopic characterization of proteasomes produced in two lid mutants, rpn5-1 and rpn7-3, and a base mutant ΔN rpn2, of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We found that, although lid formation was abolished in rpn5-1 mutant cells at the restrictive temperature, an apparently intact base was produced and localized in the nucleus. In contrast, in ΔN rpn2 cells, a free lid was formed and localized in the nucleus even at the restrictive temperature. These results indicate that the modules of the 26S proteasome, namely, the core particle, base, and lid, can be formed and imported into the nucleus independently of each other. Based on these observations, we propose a model for the assembly process of the yeast 26S proteasome.

INTRODUCTION

The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) is essential for the degradation of short-lived regulatory proteins that are involved in cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, signal transduction, apoptosis, and metabolic regulation as well as for the elimination of damaged or misfolded proteins (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998; Schwartz and Ciechanover, 1999). The 26S proteasome acts at the final step of this pathway by degrading poly-ubiquitinated substrates, thereby ensuring the irreversibility of this pathway.

The 26S proteasome is a huge multicatalytic complex consisting of >30 different components that are divided into those of the 20S core particle (CP) and the 19S regulatory particle (RP). The RP can be biochemically further divided into two substructures, the base and the lid. The base consists of six AAA-ATPase subunits, regulatory particle triple-A ATPase (Rpt)1p–Rpt6p, and three non-ATPase subunits, regulatory particle non-ATPase (Rpn)1p, Rpn2p, and Rpn13p, whereas the lid is made of nine non-ATPases, Rpn3p, Rpn5p–Rpn9p, Rpn11p, Rpn12p, and Sem1p (Rpn15p) (Glickman et al., 1998b; Leggett et al., 2002; Funakoshi et al., 2004; Sone et al., 2004). Rpn10p, a non-ATPase subunit that binds polyubiquitin (Ub) chains (van Nocker et al., 1996; Saeki et al., 2002; Elsasser et al., 2004), has been suggested to exist in the interface between the base and the lid (Fu et al., 2001).

Interestingly, the composition of the lid is surprisingly similar to that of the COP9/signalosome and the eIF3, from which Glickman et al. (1998a) proposed that these protein complexes have diverged from a common ancestor. Most of the components of these complexes share a common proteasome/COP9/Initiation factor (PCI) domain, thought to serve as a scaffold for protein–protein interaction (Hofmann and Bucher, 1998), or a catalytic MPN+ domain (Maytal-Kivity et al., 2002). Rpn11p (Verma et al., 2002; Yao and Cohen, 2002; Guterman and Glickman, 2004) and CSN5 (Cope et al., 2002), which are MPN+ domain proteins of the lid and the COP9, respectively, are the only known components to possess enzymatic activity in these complexes.

It was shown by immunoelectron microscopy (Wilkinson et al., 1998) and by fluorescence microscopy of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged proteasomes (Enenkel et al., 1999) that in yeast, 26S proteasomes were mainly localized in the nucleus, especially on the inner nuclear membrane. Based on genetic data, the involvement of importin α/β in the nuclear import of the proteasomes was suggested (Tabb et al., 2000), and it was shown that in the mutant of importin α srp1-49, seclusion of GFP-fused proteasome in the nucleus was no longer observed (Wendler et al., 2004). A study in fission yeast has shown that Cut8 is responsible for retaining the proteasome within the nucleus (Tatebe and Yanagida, 2000; Takeda and Yanagida, 2005).

The process of proteasome assembly has been a topic for recent studies and interesting facts have been elucidated. The CP, which is a stack of four seven-membered rings, in the order of α7β7β7α7, is imported into the nucleus as an α7β7 “half” proteasome (Chen and Hochstrasser, 1996; Ramos et al., 1998), and maturation is thought to take place in the nucleus (Fehlker et al., 2003). Ump1p, which associates specifically with half-proteasomes, is suggested to function as an accelerator in this process (Ramos et al., 1998). Blm10p (formerly registered as Blm3p) was reported to act as an inhibitor of premature dimerization of the half-proteasomes (Fehlker et al., 2003), but it is also suggested to be a functional homologue of the mammalian PA200, activator of the CP (Schmidt et al., 2005). Recently, a study in mammalian cells showed that PAC1 and PAC2 work during the first step of assembly of the α ring (Hirano et al., 2005).

For the assembly of the RP, no external factors are known to date. In previous studies, we have shown that partially assembled lid subcomplexes made up of five (lidrpn7-3: Rpn5p, Rpn6p, Rpn8p, Rpn9p, and Rpn11p) or four (lidrpn6-1: Rpn5p, Rpn8p, Rpn9p, and Rpn11p) components accumulate in lid mutants (Isono et al., 2004, 2005). Because Rpn5p, Rpn8p, Rpn9p, and Rpn11p were included in both subcomplexes, we proposed these to be the “core” of lid formation. In this study, based on the analysis of an rpn5 mutant and an rpn2 mutant, we show, for the first time, that the formation and nuclear import of both the lid and the base are separable processes and that Rpn5p is indeed one of the core components of the lid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Genetic Methods

Yeast strains used in this work are listed in Table 1, and plasmids used for cloning and subcloning various genes and their fragments are listed in Table 2. Cells were cultured in omission medium prepared by removing appropriate nutrient(s) from synthetic complete (SC) medium, rich medium (YPDAU) (Sherman et al., 1986), or SR-U in which 2% glucose of SC was replaced with 2% raffinose and uracil was omitted. Escherichia coli strain DH5α (supE44 ΔlacU169 [φ80lacZ ΔM15] hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1) was used for construction and propagation of plasmids. Yeast transformations were performed as described previously (Burk et al., 2000).

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| W303-1A | MATa leu2 trp1 his3 ura3 ssd1 can1 ade2 | Our stock |

| W303-1B | MATα leu2 trp1 his3 ura3 ssd1 can1 ade2 | Our stock |

| YEK5 | MATa rpn7::rpn7-3-URA3 | Isono et al. (2004) |

| YEK6 | MATα rpn7::rpn7-3-URA3 | Isono et al. (2004) |

| YEK29 | YEK5 rpn11::RPN11-3×FLAG-HIS3 | Isono et al. (2004) |

| YEK79 | MATα pre6::PRE6-GFP-TRP1 | This study |

| YEK100 | MATa rpn5::rpn5-1-TRP1 | This study |

| YEK101 | MATα rpn5::rpn5-1-TRP1 | This study |

| YEK115 | MATa rpn11::RPN11-YGFP-TRP1 | This study |

| YEK147 | MATa rpn1::RPN1-YGFP-LEU2 | This study |

| YEK209 | YEK5 rpn11::RPN11-YGFP-TRP1 | This study |

| YEK211 | YEK5 pre6::PRE6-YGFP-LEU2 | This study |

| YEK213 | YEK6 rpn1::RPN1-YGFP-LEU2 | This study |

| YEK221 | MATα rpn7::RPN7-3×FLAG-KanMX | This study |

| YEK225 | YEK100 rpn7::RPN7-3×FLAG-KanMX | This study |

| YEK234 | YAT2433 rpn1::RPN1-3×FLAG-HIS3 | This study |

| YEK235 | YAT2433 rpn1::RPN1-YGFP-LEU2 | This study |

| YEK236 | YAT2433 rpn11::RPN11-YGFP-TRP1 | This study |

| YEK246 | YAT2433 srp1::srp1-49-LEU2 | This study |

| YEK247 | YAT2433 srp1::srp1-49-LEU2 rpn7::RPN7-YGFP-URA3 | This study |

| YEK248 | YAT2433 srp1::srp1-49-LEU2 rpn1::RPN1-YGFP-URA3 | This study |

| YKN6 | YEK100 pre1::PRE1-3×FLAG-HIS3 | This study |

| YKN8 | YEK100 rpn1::RPN1-3×FLAG-HIS3 | This study |

| YKN16 | YEK100 rpn1::RPN1-YGFP-LEU2 | This study |

| YKN18 | YEK101 pre6::PRE6-YGFP-TRP1 | This study |

| YAT2433 | MATα Δrpn2-TRP1 [Top2612] | This study |

| YAT3507 | YAT2433 rpn11::RPN11-3×FLAG-LEU2 | This study |

| YYS37 | MATa pre1::PRE1-3×FLAG-HIS3 | Saeki et al. (2002) |

| YYS39 | MATa rpn1::RPN1-3×FLAG-HIS3 | Saeki et al. (2002) |

| YYS40 | MATa rpn11::RPN11-3×FLAG-HIS3 | Saeki et al. (2002) |

All strains are in the W303 background.

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pRS304 | TRP1 Ampr | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pRS313 | HIS3 CEN Ampr | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| Ub-A-lacZ | GAL1p-Ub-A-lacZ URA3 Ampr | Bachmair et al. (1986) |

| Ub-R-LacZ | GAL1p-Ub-R-lacZ URA3 Ampr | Bachmair et al. (1986) |

| Ub-P-lacZ | GAL1p-Ub-P-lacZ URA3 Ampr | Bachmair et al. (1986) |

| pTS901CL | 5×HA CEN LEU2 Ampr | Sasaki et al. (2000) |

| pEK152 | RPN11-YGFP-TRP1 Ampr | This study |

| pEK165 | PRE6-YGFP-TRP1 Ampr | This study |

| pEK221 | RPN5(−400bp ORF∼+1kb ORF) HIS3 CEN Ampr | This study |

| pEK252 | RPN1-YGFP-LEU2 Ampr | This study |

| pEK285 | NUP53-mRFP-LEU2 CEN Ampr | This study |

| pEK291 | RPN7-YGFP-URA3 Ampr | This study |

| pEK296 | RPN1-YGFP-URA3 Ampr | This study |

| pEK297 | RPN3-YGFP-URA3 CEN Ampr | This study |

| pEK298 | RPN7-YGFP-URA3 CEN Ampr | This study |

| pEK299 | RPN12-YGFP-URA3 CEN Ampr | This study |

| pEK300 | RPN15-YGFP-URA3 CEN Ampr | This study |

| pNS101 | RPN5 TRP1 Ampr | This study |

| pNS202 | GST-RPN5 Ampr | This study |

| TOp2612 | ΔN rpn2 (+437∼+2838) HIS3 CEN Ampr | This study |

Isolation of Temperature-sensitive Mutants

Temperature-sensitive rpn5 mutants were screened as described previously (Isono et al., 2005). The RPN5 gene was amplified using primers Rpn5 Mut1 (BglII) 5′-GGCCAAGATTGTAGATCTGCTAGC-3′ and Rpn5 Mut2 (NotI) 5′-GGAAGCGGCCGCAACCAGGCTTGAGTTAAC-3′ and cloned between the BamHI–NotI sites of the YIp vector pRS304. The resulting plasmid pNS101 was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mutagenesis.

Gel Filtration

Total proteins (5 mg) were resolved on a Superose 6 column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) as described previously (Isono et al., 2005). For the subsequent fractionation of Superose 6-fractionated samples, 450 μl of the separated samples were applied onto a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) connected to a fast-performance liquid chromatograph (GE Healthcare) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, and 500-μl serial fractions were collected using a fraction collector FRAC-100 (GE Healthcare).

Microscopy

Cells harboring GFP- or monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP)-fused proteins were photographed by using a BX52 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a UPlanApo 100×/1.45 objective (Olympus) equipped with a confocal scanner unit CSU20 (Yokogawa Electric, Tokyo, Japan) and an EMCCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Bridgewater, NJ). GFP and mRFP were excited using the 488- and 568-nm Ar/Kr laser lines with GFP and RFP filters (Semrock, Rochester, NY), respectively. DNA stained with Hoechst 33342 was photographed using a 405-nm laser line with a UV filter (Semrock). Images were obtained and processed using the IPLab software (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA) and processed using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA). For DNA staining, a final concentration of 20 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the cell suspension and incubated for 10 min at either 25 or 37°C under a light shade.

Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP)

Samples used for FRAP experiments were embedded in agarose in the following way with modifications of the methods described previously (Hoepfner et al., 2000). First, 100 μl of 1.7% agarose (Takara, Kyoto, Japan) dissolved in filtrated SC media was dropped on a prewarmed holed glass slide (Toshinriko, Tokyo, Japan), and immediately covered with a coverslip (Matsunami Glass, Osaka, Japan). Excess agarose was removed, and the glass slide was cooled until the agarose was set. The coverslip was carefully removed, and 3 μl of freshly cultured cells was dropped on the agarose plane and covered with a new coverslip and sealed. FRAP experiments were performed using a confocal laser-scanning microscope LSM510 META (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a Plan-APOCHROMAT 100×/1.4 objective (Carl Zeiss). GFP was excited using the 488-nm laser lines from an Ar ion laser and a GFP filter. Photobleaching was achieved by scanning the selected region with maximal output of the 488-nm laser, and the recovery of the fluorescent signal was observed at the indicated time points under the same recording conditions as at 0 min. The stage was kept at 37°C with a stage-heater MATS-525F (Tokai Hit, Shizuoka, Japan). Fluorescence intensity of the original data was quantified using the LSM510 software, and images were processed with Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems).

Indirect Immunofluorescence Method

For fixation, 420 μl of 37% formaldehyde was added to 3 ml of logarithmically growing cell culture (OD600 = 0.8–1.0) and incubated for 30 min at the incubation temperature. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 500 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-formaldehyde (PBS/formaldehyde, 10:1) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. For spheroplasting, cells were incubated with 200 μl of PBS-zymolyase (20 μg of zymolyase 100T [Seikagaku America, Rockville, MD]/1 ml of PBS) for 20 min at 30°C. Cells were then incubated in 200 μl of PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. After washing twice, cells were resuspended in 200 μl of 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS for blocking and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; 1/200 dilution) or anti-Rpn5p (1/100 dilution) antibody was used as primary antibody. Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes, 1/400 dilution) or Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1/400 dilution; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used as a secondary antibody. DNA was stained with 0.5 μg/ml 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma- Aldrich).

RESULTS

Isolation of the Temperature-sensitive rpn5-1 Mutant

In our previous study, we found that partially assembled lid subcomplexes accumulated in temperature-sensitive lid mutants. Five (Rpn5p, Rpn6p, Rpn8p, Rpn9p, and Rpn11p) or four (Rpn5p, Rpn8p, Rpn9p, and Rpn11p) out of the nine components of the lid formed a stable complex in lid mutants, rpn7-3 (Isono et al., 2004) and rpn6-1/rpn6-2 (Isono et al., 2005), respectively. From these results and the fact that RPN9 is a nonessential gene, we hypothesized that Rpn5p, Rpn8p, and Rpn11p may play pivotal roles in producing the core of the lid. To examine this hypothesis, we first focused on the function of Rpn5p.

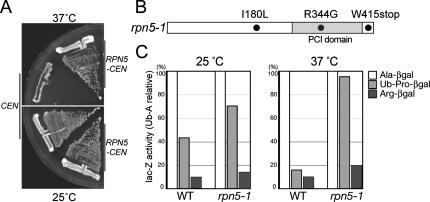

To start with, we generated a temperature-sensitive mutant allele of RPN5 by PCR-based random mutagenesis (Cadwell and Joyce, 1992; Toh-e and Oguchi, 2000) and named it rpn5-1. The rpn5-1 mutant grew normally at 25°C, but it stopped growth after 6–8 h at 37°C (data not shown). The growth defect of the rpn5-1 mutant at 37°C was complemented by a single copy of the wild-type RPN5 gene, proving that the temperature sensitivity is due to a mutation within the RPN5 gene and that the rpn5-1 mutation is not dominant (Figure 1A). Sequencing analysis revealed that the rpn5-1 open reading frame (ORF) possessed three mutations (Figure 1B), of which I180L or R344G alone did not lead to temperature-sensitive growth when introduced into the wild-type background. The nucleotide substitution from G to A at the 1245th nucleotide, leading to a nonsense mutation at the 415th tryptophan was found to be responsible for the temperature sensitivity (data not shown). Amounts of Rpn5-1p along with other proteasomal components were not significantly changed during incubation at the restrictive temperature, whereas a slight mobility shift of Rpn5-1p was observed due to the C-terminal truncation (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characterization of the temperature-sensitive rpn5 mutant. (A) rpn5-1 (YEK100) cells carrying either a CEN vector (pRS314) or RPN5-CEN plasmid (pEK221) were streaked on YPDAU plates and photographed after incubating for 2 d at either 25 or 37°C. (B) Amino acid substitution in rpn5-1. The nucleotide sequence of the rpn5-1 ORF was determined by the dideoxychain termination method and compared with that of the wild-type RPN5 ORF. Gray, PCI domain. (C) Degradation of N-end rule pathway- and UFD pathway-substrates. Wild-type (W303-1A) and rpn5-1 (YEK100) cells were transformed with plasmids expressing an N-end rule model substrate Ub-Ala-βgal or Ub-Arg-βgal, or a UFD pathway substrate Ub-Pro-βgal. Production of the model substrates was induced by adding 2% galactose to SR-U medium. Cells were harvested after 4 h of induction at either 25 or 37°C, and steady-state levels of β-galactosidase activity were assayed. The amounts of Ub-Pro-βgal and Arg-βgal are indicated relative to that of Ala-βgal. Average of three independent experiments is shown (open, Ala-βgal; light gray, Ub-Pro-βgal; and solid, Arg-βgal).

To examine the effect of the rpn5-1 mutation on the UPS, we evaluated the stability of three model substrates of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, namely, Ala-βgal, Arg-βgal, and Ub-Pro-βgal (Bachmair et al., 1986). Whereas Ala-βgal is stable, Arg-βgal, and Ub-Pro-βgal are short-lived substrates of the N-end rule- and Ub-fusion degradation (UFD) pathway, respectively. Wild-type and rpn5-1 mutant cells, transformed with plasmids expressing one of these substrates under a galactose inducible promoter were cultured at either 25 or 37°C. After 3 h, galactose was added to the culture to induce the production of the substrates, and cells were incubated for further 4 h. Total extract was prepared from each culture, and steady-state levels of the substrates were estimated by β-galactosidase assay. Compared with the wild-type cells, rpn5-1 cells maintained the normally short-lived Arg-βgal and Ub-Pro-βgal at a higher level, especially at 37°C, indicating that the rpn5-1 mutation caused a defect in the UPS at the restrictive temperature (Figure 1C).

Assembly of the Lid in rpn5-1 Mutants

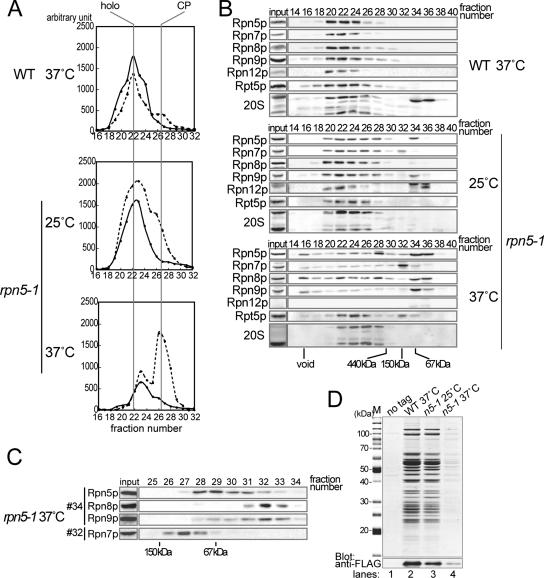

In a previous report on a Δrpn5 mutant in fission yeast, the state of assembly of each substructure of the 26S proteasome was ambiguous, because Rpn10p that is not stably associated with the base or the lid was used for the affinity purification of proteasomes (Yen et al., 2003a). To examine the assembly of the 26S proteasome in the rpn5-1 mutant, we compared the gel filtration profile of proteasomes in wild-type and rpn5-1 extracts. Wild-type and rpn5-1 cells were cultured for 7 h at 37°C in YPDAU, and total lysates were prepared in the presence of ATP and MgCl2. Extract equivalent to 5 mg of protein was resolved on a Superose 6 gel filtration column, and the eluate was collected into 500 μl of sequential fractions. Relevant fractions (16∼32) were subjected to peptidase activity measurement by using succinyl-leucyl-leucyl-valyl-tyrosyl-methycoumaryl-7-amide (Suc-LLVY- MCA), a fluorogenic peptide substrate. In the wild-type sample, the most enzymatically active fraction was at 22, showing this fraction to be the peak fraction of the 26S holoenzyme (Figure 2A, top).

Figure 2.

Lid formation in rpn5-1 cells. Wild-type (W303-1A) and rpn5-1 (YEK100) cells were cultured for 7 h at the indicated temperature, and total cell extracts were prepared by breaking the cells by glass-beads under the existence of ATP and MgCl2. (A) Gel filtration. Peptidase activity toward the fluorogenic substrate Suc-LLVY-MCA was measured in relevant fractions (16–32). Positions of the 26S holoenzyme and the CP are indicated at the top of the graph. Solid line, without SDS; and dotted line, with 0.02% SDS. (B) Western blotting. Twenty microliters of each of the even numbered fractions was mixed with SDS-PAGE loading buffer and resolved by 12.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and proteasome subunits were detected by Western blotting by using the indicated antibodies (Rpn5p, Rpn7p, Rpn8p, Rpn9p, and Rpn12p, lid; and Rpt5p, base) Positions of the void fraction and marker proteins (ferritin [440 kDa], aldolase [150 kDa], and bovine serum albumin [67 kDa]) are indicated at the bottom of the panels. (C) Second gel filtration. Fractions 32 and 34 in Superose 6 gel filtration of rpn5-1 extracts (37°C) in A were subsequently resolved by a Superdex 200 gel filtration column. Five hundred microliters sequential fractions were collected, and relevant fractions were subjected to Western blotting as in B. Antibodies used are indicated on the left. Positions of marker proteins (aldolase [150 kDa] and bovine serum albumin [67 kDa]) are indicated on the bottom of the panels. (D) Wild-type and rpn5-1 strains expressing RPN7-3xFLAG (YEK221 and YEK225, respectively) along with the untagged wild-type strain (W303-1A) were cultured for 7 h at 25 or 37°C as indicated, and extract was prepared from each culture. Proteasomes were affinity purified using anti-FLAG agarose. Purified products were run on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel, and protein bands were stained with CBB (M, marker).

In contrast, in gel filtration of extract prepared from 37°C-grown rpn5-1 cells, the peak at fraction 22 has almost vanished, suggesting that the assembly of the 26S proteasome is disturbed. On SDS treatment, which activates free CPs, a high enzyme activity occurred at fractions 26 and 27, indicating that there is a large pool of free CPs in rpn5-1 cells grown at 37°C (Figure 2A, bottom). There was also a small peak in fraction 23, the identity of which will be discussed later. rpn5-1 cells cultured at 25°C had almost the same profile as the wild-type, except that the peak of enzyme activity at fraction 26 was higher than that in the wild-type sample (Figure 2A, middle).

Fractions were then subjected to Western blotting by using antibodies against proteasome components. CP signals were detected around fraction 22 in the wild type sample, whereas they were detected around fraction 26 in the sample derived from rpn5-1 cells grown at 37°C, in accordance with the result of activity measurement (Figure 2B, top and bottom). Interestingly, all lid components of rpn5-1 cells grown at 37°C, but not at 25°C, were detected in low-molecular-mass fractions (Figure 2B, middle and bottom). To investigate whether they are monomers or forming a complex, we further resolved fractions 32 and 34 by Superdex 200, and fractions were subjected to Western blotting (Figure 2C). Comparison with marker proteins indicated that at least Rpn5p (52 kDa), Rpn8p (38 kDa), and Rpn9p (46 kDa) existed in a free form. Rpn7p (49 kDa) was found to move slower than expected from its molecular mass.

To see whether Rpn7p forms a stable complex with any other components in rpn5-1 cells, we generated rpn7:: RPN7-3xFLAG strains with or without the rpn5-1 mutation and performed affinity purification. RPN7-3xFLAG RPN5 and RPN7-3xFLAG rpn5-1 strains were cultured at either 25 or 37°C for 7 h and proteasomes were affinity purified by anti-FLAG antibody immobilized on agarose from total lysates. Purified proteasomes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB), and the band patterns were compared with purified authentic proteasomes (Saeki et al., 2005). All components of the 26S proteasome were copurified with Rpn7p-3xFLAG in wild-type cells and rpn5-1 cells cultured at 25°C (Figure 2D, lanes 2 and 3; data for wild-type 25°C not shown). However, no protein was copurified with Rpn7p-3xFlag from rpn5-1 cells cultured at 37°C. Because Rpn7p-3xFLAG was present in the total extract at both 37 and 25°C (Supplemental Figure 2), Rpn7p is probably not forming a soluble and stable complex with other components in rpn5-1 cells under the restrictive conditions.

Base-CP Complexes in rpn5-1

The base and the CP of the extract prepared from rpn5-1 cells incubated at 37°C seemed to comigrate (Figure 2B). Results of nondenaturing PAGE of total lysates of wild-type or rpn5-1 cells grown at 37°C showed the existence of base-CP complexes, B1CP, and B2CP, in rpn5-1 cells (Figure 3A). The peak of peptidase activity observed in fraction 23 in the rpn5-1 sample grown at 37°C (Figure 2A, bottom) was likely due to these base–CP complexes. We next tried to affinity-purify these base–CP complexes by using CP- or base-tagged strains. However, as shown in Figure 3B, no base–CP complex was obtained from rpn5-1 cells regardless of the tagged subunit used, suggesting that the base-CP interaction in rpn5-1 cells is unstable.

Figure 3.

Proteasome species in wild-type extract and rpn5-1 extract. (A) Extracts were prepared from wild-type (W303-1B) or rpn5-1 (YEK101) cells incubated for 7 h at 37°C, and extract equivalent to 50 μg of protein was resolved by nondenaturing PAGE. Proteasomes were visualized by overlaying buffer containing 0.1 mM Suc-LLVY-MCA and 0.05% SDS on the gel (far left). The gels were subsequently subjected to Western blotting by using antibodies indicated on the bottom of the panels (Rpt5p, base; and Rpn5p and Rpn7p, lid). Bands corresponding to various proteasome species are indicated on the far left of the panels (R, RP; C, CP; and b, base). (B) Affinity purification of proteasomes from CP- and base-tagged stains. YYS37 (PRE1-3xFLAG) and YYS39 (RPN1-3xFLAG), YKN6 (rpn5-1 PRE1-3xFLAG) and YKN8 (rpn5-1 RPN1-3xFLAG) cells were cultured for 7 h at 37°C and proteasomes were affinity purified from 2 mg of total proteins using anti-FLAG agarose. The purified proteasomes were resolved on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and stained with CBB (left, CP tagged; and right, base tagged). Bands corresponding to the tagged components are indicated with solid arrowheads. The approximate migrating positions of the base and the CP components are indicated by bars on the right side of the panel.

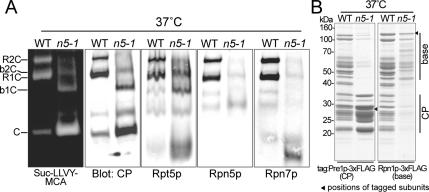

Assembly of the Lid in a Base Mutant ΔN rpn2

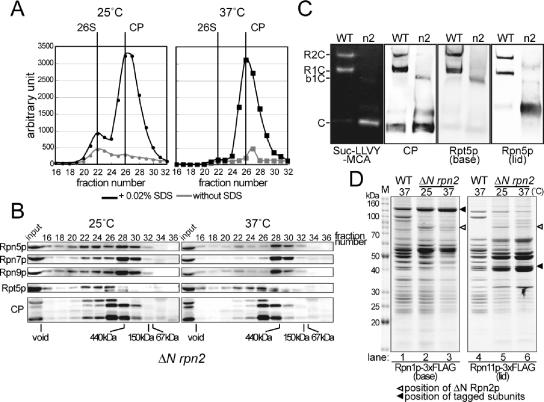

In the previous section, we showed that the base was produced independently of the assembly of the lid. Next, we ask the following question: Are the lid and the base assembled independently to each other? To address this issue, we examined the status of lid assembly in a temperature-sensitive base mutant of RPN2 termed ΔN rpn2 (equivalent to rpn2Δ described by Yokota et al. 1996. ΔN rpn2 is a mutant that carries an N-terminal truncated (Δ1-220aa) version of RPN2 in a null rpn2 strain. It stopped growth after 4–6 h at 37°C (data not shown). To see the assembly state in this mutant, total lysates were prepared from ΔN rpn2 cells grown for 6 h at either 25 or 37°C, and 5 mg of total proteins was resolved on a Superose 6 gel filtration column.

The ΔN rpn2 mutant was found to have a more severe defect in the structure of proteasomes than the rpn5-1 mutant, because peptidase assays and Western blotting both showed reduced amount of the 26S holoenzyme even at the permissive temperature (Figure 4, A and B, left). The defects were strongly enhanced when cells were grown at the restrictive temperature. Peptidase activity measurement showed that in ΔN rpn2 cells incubated at 37°C, the peak corresponding to the 26S proteasome was almost completely lost, and a single high peak of free CPs was detected at fraction no.26 (Figure 4A, right).

Figure 4.

Lid formation does not depend on the binding of the lid to the base. (A) Extract of ΔN rpn2 (YAT2433) cells cultured for 6 h at 25 or 37°C was resolved on a Superose 6 column, and peptidase activity was measured as described in Figure 2A. Positions of the 26S holoenzyme and the CP are indicated at the top of the graph (black lines, with 0.02% SDS; and gray lines, without SDS). (B) Fractions were subjected to Western blotting as described in Figure 2B. Antibodies used are indicated on the left of the panel (Rpn5p, Rpn7p, and Rpn9p, lid; and Rpt5, base). Positions of the void fraction and marker proteins (ferritin [440 kDa], aldolase [150 kDa], and bovine serum albumin [67 kDa]) are indicated at the bottom of the panels. Note that all lid components examined comigrated. (C) Wild-type (W303-1A) or ΔN rpn2 (YAT2433) cells were cultured for 6 h at 37°C, and extract was prepared as described above. Extract equivalent to 50 μg of protein was resolved by nondenaturing PAGE. Proteasomes were visualized by overlaying buffer containing 0.1 mM Suc-LLVY-MCA and 0.05% SDS on the gels (far left panel). The same gels were subsequently subjected to Western blotting by using antibodies indicated on the bottom of the panels (Rpt5p, base; and Rpn5p, lid). Bands corresponding to various proteasome species are indicated on the far left of the panels (R, RP; C, CP; and b, base). (D) Affinity purification of proteasomes from base- and lid-tagged strains YYS39 (RPN1-3xFLAG), YYS40 (RPN11-3xFLAG), YEK234 (ΔN rpn2 RPN1-3xFLAG), and YAT3507 (ΔN rpn2 RPN11-3xFLAG) cells were cultured for 6 h at 25 or 37°C as indicated, and proteasomes were affinity-purified using anti-FLAG agarose. The purified proteasomes were resolved on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and stained with CBB (left, base tagged; and right, lid tagged). Protein bands were cut out and identified by mass spectrometry (see Supplemental Figure 2). The approximate migrating positions of base and lid components are indicated on the right of the panel (solid arrowhead, tagged component; open arrowhead, ΔN Rpn2p; and M, marker).

Western blotting of chromatographic fractions (Figure 4B, right) revealed that all lid components tested were detected in fraction no.28, which is comparable with the eluting position of a free lid (ca. 500 kDa). These results suggest that in ΔN rpn2 under the restrictive condition, the lid exists in a free form, unbound to the base. Indeed, this was confirmed by native PAGE (Figure 4C) and affinity purification by using Rpn11p-3xFLAG (lid), by which a complete lid was affinity purified from ΔN rpn2 cells (Figure 4D, lane 6). The incorporation of all of the nine lid components was verified by band comparison with a wild-type lid and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (Supplemental Figure 2). It was also shown that a ΔN Rpn2p-less base was formed in ΔN rpn2 cells at the restrictive temperature (Figure 4D, lane 3). Together with the results of the rpn5-1 extract, we conclude that the base formation and the lid formation can be independent of each other and are separable processes.

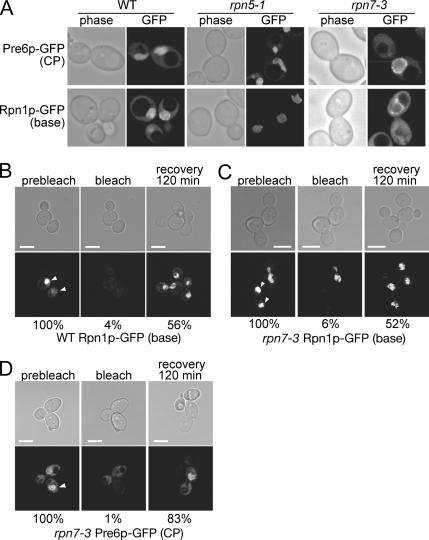

Localization of the Base and the CP in Lid Mutants

In yeast, the 26S proteasome is known to be highly enriched in the nucleus (Wilkinson et al., 1998; Enenkel et al., 1999). Biochemical analysis described above has shown that the lid formation was independent of the base formation. It is not known to date whether the assembly of the base and the lid into an RP is a prerequisite for their nuclear localization. To observe the localization of proteasomes in lid mutants, we generated GFP (Cormack et al., 1996)-fused proteasomes, PRE6-GFP (CP), RPN1-GFP (base), and RPN11-GFP (lid) strains, in which one of the chromosomal PRE6, RPN1, and RPN11 genes had been replaced with a C-terminally GFP-tagged gene, and the incorporation of the GFP-fused proteins into the proteasome were verified (Supplemental Figure 3).

Rpn1p-GFP and Pre6p-GFP showed strong nuclear localization in wild-type cells regardless of the incubating temperature (Figure 5A, left; data for 25°C not shown) as reported previously (Enenkel et al., 1999; Wendler et al., 2004). The localization was also examined in two lid mutants, rpn5-1 and rpn7-3, in which the base was not associated with the lid under restrictive conditions. Both base and CP signals were observed in the nucleus regardless of the cultivation conditions (Figure 5A, middle and right), indicating that the rpn5-1 and rpn7-3 mutations that perturb the interaction between the lid and the base do not affect the nuclear localization of the base and the CP and that the nuclear localization of the base and the CP is independent of the binding of the lid to the base.

Figure 5.

The base and the CP are localized in the nucleus in lid mutants even at the restrictive temperature. (A) Wild-type, rpn5-1 and rpn7-3 cells producing Pre6p-GFP (CP) or Rpn1p-GFP (base) instead of the authentic Pre6p and Rpn1p, respectively, were cultured for 7 h at 37°C and photographed under a confocal microscope. Strains used were PRE6-GFP (CP), wild type (YEK79), rpn5-1 (YKN18), rpn7-3 (YEK211), and RPN1-GFP (base) wild type (YEK147), rpn5-1 (YKN16), rpn7-3 (YEK213). (B–D) The base and the CP are imported into the nucleus after shift to the restrictive temperature. Rpn1p-GFP (base) producing wild-type (YEK147) and Rpn1p-GFP or Pre6p-GFP (CP) producing rpn7-3 (YEK213 and YEK211, respectively) cells were cultured for 6 h at 37°C and embedded in agarose as described in Materials and Methods. GFP signals in the nucleus (prebleach, left) were photobleached with intense laser (bleach, middle), and FRAP was observed and photographed after 120 min (recovery, right). The stage was kept at 37°C throughout the experiment. Fluorescence intensity ([/mm2] − background [/mm2]) was quantified and shown as a relative value to the prebleach intensity at the bottom of each panel. The mean value of two independent experiments is shown. Bar; 5 μm.

FRAP Experiments

One concern was that the base and CP signals detected at the restrictive temperature might be those of the remaining proteins synthesized and imported under the permissive temperature. To test this possibility, we observed the FRAP, by bleaching the nuclear region with intense laser and observing the recovery of fluorescence after 120 min.

We first carried out an experiment using a wild-type strain producing Rpn1p-GFP instead of Rpn1p. The GFP signals indeed vanished after photobleaching the region of the nucleus (Figure 5B, left and middle). When observed at 120 min after photobleaching, the GFP fluorescence occurred in the nucleus again, proving that nuclear import of the base has occurred (Figure 5B, right). Next, the recovery from photobleaching in rpn7-3 cells was similarly examined using rpn7-3 strains expressing RPN1-YGFP and PRE6-YGFP. Cells were held under the restrictive condition by keeping the glass slides at 37°C by using a stage heater. In rpn7-3 cells, recovery of both base and CP signals were observed even at the restrictive temperature (Figure 5, C and D). The fluorescence intensity in the nucleus was quantified and the degree of fluorescence recovery in rpn7-3 cells was found to be comparable with that in the wild-type cells (Figure 5, C and D).

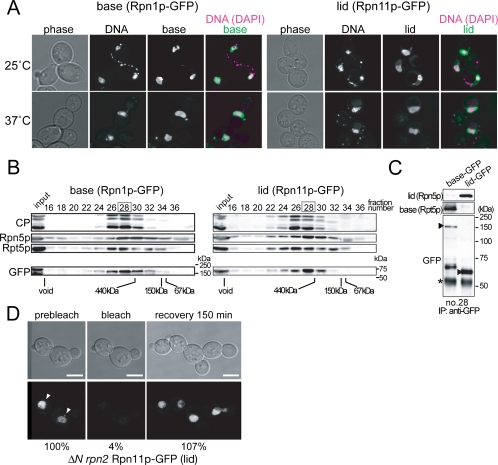

Localization of the Free Lid in ΔN rpn2 Cells

One of the striking features of the ΔN rpn2 mutant is that its lid exists as a free complex. Because in no known mutant was the lid separated from the base in vivo, it has been difficult to examine whether the lid and the base could be imported into the nucleus independent of each other. We used the ΔN rpn2 strain to observe the localization of the free lid along with the base by creating its RPN11-GFP (lid) or RPN1-GFP (base) derivative (Figure 6). Surprisingly, not only the base but also the lid was localized in the nucleus even at 37°C, suggesting that the import of the lid and the base does occur independently. It was verified by gel filtration (Figure 6B) and subsequent immunoprecipitaiton (Figure 6C) that the GFP signals corresponded to the respective complexes. The import of the lid into the nucleus under the restrictive condition was further corroborated by performing FRAP experiments (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

The nuclear import of the base and the lid are independent of each other. (A) ΔN rpn2 cells producing Rpn1p-GFP (base, YEK235) or Rpn11p-GFP (lid, YEK236) instead of the authentic Rpn1p or Rpn11p, respectively, were cultured for 6 h at either 25 or 37°C and photographed under a confocal microscope. DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342. (B) Total proteins were extracted from the cells cultured at 37°C as described in A and subjected to gel filtration by using a Superose 6 column. Fractions were subsequently subjected to Western blotting by using the antibodies indicated on the left of the panels. (Rpn5p; lid, Rpt5p; base) Positions of the void fraction and marker proteins (ferritin [440 kDa], aldolase [150 kDa], and bovine serum albumin [67 kDa]) are indicated at the bottom of the panels. For the GFP blot, positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the right of each of the panels. (C) Immunoprecipitation was performed against fraction 28 in B by using anti-GFP antibody and analyzed by Western blotting by using anti-Rpn5p (lid), anti-Rpt5p (base), and anti-GFP antibodies. Asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. Arrowheads indicate the GFP-fused components. (D) RPN11-GFP–expressing ΔN rpn2 (YEK256) cells were cultured for 6 h at 37°C, and FRAP experiments were performed as in Figure 5, except that the recovery was observed after 150 min. Fluorescence intensity ([/mm2] − background [/mm2]) was quantified and shown as relative values to the prebleach intensity at the bottom of each panel. The mean value of two independent experiments is shown. Arrowheads indicate the cell that was photobleached. Bar; 5 μm.

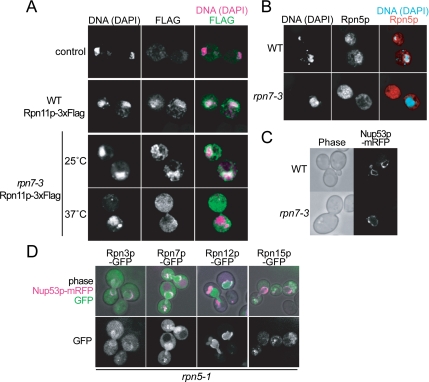

Localization of lidrpn7-3 in rpn7-3 Cells

In the previously characterized rpn7-3 mutant, it was shown that five of the nine lid components formed a subcomplex termed lidrpn7-3 (Isono et al., 2004). To see whether this partially assembled lidrpn7-3 could be imported into the nucleus, we attempted to analyze the localization of lidrpn7-3 in the RPN11p-GFP rpn7-3 strain. However, because Rpn11p-GFP was not incorporated into lidrpn7-3 at the restrictive temperature (data not shown), we observed its localization by using the indirect immunofluorescence method. RPN11-3xFLAG wild-type and RPN11-3xFLAG rpn7-3 cells were cultured for 7 h at 37°C, fixed, and stained. In wild-type cells and rpn7-3 cells cultured at 25°C, the signal corresponding to the 26S proteasome was clearly nuclear localized, and strong signals at the nuclear periphery was observed (Figure 7A, second and third panels from the top; data for 25°C wild-type samples not shown). On the contrary, in rpn7-3 cells cultured at 37°C, the nuclear localization was not seen, and signals of DAPI-stained DNA did not merge with the FLAG signals any more (Figure 7A, lowermost panel), showing that the lidrpn7-3 was not localized in the nucleus.

Figure 7.

Localization of the partially assembled lidrpn7-3. (A) RPN11-3xFLAG (YYS40) and rpn7-3 RPN11-3xFLAG (YEK29) cells, along with untagged wild-type (W303-1A) cells, were cultured for 6 h at 25 or 37°C as indicated, and localization of lidrpn7-3 was detected by the indirect immunofluorescence method by using anti-FLAG M2 antibody. Photographs were taken under a confocal microscope. DNA was stained with DAPI. (B) Wild-type (W303-1B) and rpn7-3 (YEK6) cells were incubated for 6 h at 37°C, and localization of Rpn5p was detected as described in A by the indirect immunofluorescence method except that an anti-Rpn5p antibody was used. DNA was stained with DAPI. (C) The nuclear envelope is normal in rpn7-3 cells under the restrictive condition. Nup53p-mRFP (pEK285) was produced in wild-type (W303-1A) and rpn7-3 (YEK6) cells cultured at the same condition as described in B and photographed under a confocal microscope. (D) Localization of Rpn3p- GFP (pEK297), Rpn7p-GFP (pEK298), Rpn12p-GFP (pEK299), or Rpn15p-GFP (pEK300) in rpn5-1 (YEK100) cells. Cells were cultured for 8 h at 37°C, and GFP signals were photographed under a confocal microscope. Nup53p-mRFP was used as a marker for the nuclear envelope.

To confirm this observation, immunostaining was also performed using an antibody against Rpn5p, one of the components of lidrpn7-3. Again, the nuclear localization seen in wild type cells could not be observed in the rpn7-3 cells, in which signals of Rpn5p were detected dispersed in the cytosol (Figure 7B). This result suggests that the lid is built up in the cytosol and then imported into the nucleus to be assembled into the 26S complex, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the lidrpn7-3 is reexported to the cytosol after carried into the nucleus. The structure of the nucleus itself was not damaged in rpn7-3 cells under the restrictive condition, which was verified by the normal localization of mRFP (Campbell et al., 2002) fused Nup53p, a component of the nuclear pore complex, in wild-type and also in rpn7-3 cells at 37°C (Figure 7C).

From the above-mentioned results, we anticipated that the components not included in the lidrpn7-3, namely, Rpn3p, Rpn7p, Rpn12p, and Rpn15p, might be responsible for the import of the lid. To test this possibility, we expressed one of the GFP-fused constructs of RPN3, RPN7, RPN12, or RPN15 under their native promoters in rpn5-1 cells. The cells were cultured for 7 h at 37°C and GFP signals were observed under a confocal microscope (Figure 7D). Rpn3p, Rpn7p, and Rpn12p showed nuclear localization, whereas Rpn15p did not, showing that Rpn3p, Rpn7p, and Rpn12p can be localized in the nucleus as monomers under these conditions.

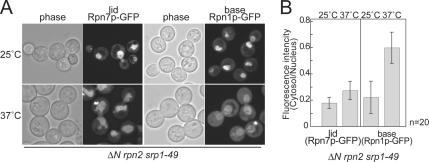

The Nuclear Import of the Lid Does Not Depend on Srp1p

Srp1p, karyopherin α, was reported to be involved in the import of proteasomes into the nucleus (Tabb et al., 2000; Lehmann et al., 2002; Wendler et al., 2004). In accordance with previous reports, in a temperature-sensitive mutant of SRP1 termed srp1-49, Rpn11p-GFP (lid) and Rpn1p-GFP (base) were delocalized (Supplemental Figure 4). However, because no method has been available to form the lid and the base separately in vivo, it had been impossible to examine whether their nuclear import would be dependent on Srp1p.

To address this issue, we took advantage of the ΔN rpn2 mutant, in which the lid exists as a free complex at the restrictive temperature. Either RPN7-GFP or RPN1-GFP was introduced into the ΔN rpn2 srp1-49 double mutant to replace each of the authentic genes. Cells were cultured for 8 h at 37°C and observed under a confocal microscope. Although the base lost its strong nuclear localization seen at 25°C, and a part of the signals was dispersed in the cytosol, the lid signals remained strongly in the nucleus at 37°C (Figure 8A), which was corroborated by the quantification of the fluorescence signals (Figure 8B). These results suggest that the nuclear import of the base is dependent on Srp1p, whereas that of the lid does not.

Figure 8.

Nuclear localization of the base, but not the lid, is affected by srp1-49. (A) ΔN rpn2 srp1-49 cells expressing Rpn7p-GFP or Rpn1p-GFP (YEK247 and YEK258, respectively) were cultured for 8 h at either 25 or 37°C, and localization of the GFP-fused components was observed under a confocal microscope. (B) Signals of A were quantified (fluorescence intensity per area) using the IPLab software, and ratio of the nuclear and cytosolic signals is shown. Error bars represent SD (n = 20).

DISCUSSION

The RPN5 gene, originally named non-ATPase subunit 5 (NAS5), is an essential gene in S. cerevisiae, in contrast to Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and is a homologue of human p55 (Finley et al., 1998). In this study, we have shown that in rpn5-1 cells, not even a partially assembled subcomplex of the lid was detected at the restrictive temperature (Figure 2, B–D). This result, together with our previous reports, indicates that the mutation in Rpn5p inhibits the complex formation of the lid, and thus Rpn5p is a key component in the core formation of the lid. A very recently published report has shown the interaction between subunits of the RP by tandem MS analysis (Sharon et al., 2006). Using this novel approach, it was demonstrated that Rpn5p, Rpn8p, Rpn9p, and Rpn11p is forming a stable soluble subcomplex and a subunit interaction map was proposed, which is in good accordance with our results that Rpn5p is a core component in lid formation.

Interestingly, the addition of a 3xFLAG tag at the C terminus to another lid component Rpn11p rescued the temperature-sensitivity of rpn5-1 and at the same time its defect in assembling the 26S proteasome (Supplemental Figure 6). Probably, the C terminus of Rpn11p is located near to the C terminus of Rpn5p so that its extension suppresses the structural alternation of the proteasome caused by the incorporation of the truncated Rpn5-1p. Because the structural recovery of the 26S proteasome led to a complete growth recovery at the restrictive temperature, the rpn5-1 mutation was probably causing purely structural defects.

The fact that the base-CP interaction in mutant cells is unstable indicates the possibility that the lid functions to strengthen the base-CP binding by allosterically affecting the base-CP interface. This result is in contrast to a previous report in which a base-CP complex was purified from a mutant of RPN11 termed mpr1–1 in the absence of the lid (Verma et al., 2002). We have no explanation for this discrepancy at present.

In fission yeast, it was proposed that SpRpn5, together with the human breast cancer related gene Int6/Yin6, serves for the nuclear localization of the lid (Yen et al., 2003b), although our results showed that the lidrpn7-3 containing Rpn5p was not localized in the nucleus (Figure 7, A and B). One explanation of these seemingly controversial results may be that there is no Int6/Yin6 homologue in budding yeast and hence the Int6/Yin6 associated function of Rpn5p is not conserved in the two yeast species.

The CP and an interacting ATPase exist already in prokaryotic organisms. Given that the lid shares its origin with COP9/signalosme and eIF3, both of which are functioning as a single complex, it is reasonable that the formation and the nuclear localization of the base and the lid are independent to each other. However, although the base is imported into the nucleus via the Srp1p-dependent importin α/β pathway, the lid seems to be carried into the nucleus via another system that is independent of Srp1p (Figure 8, A and B). As for the base, two of the base components, Rpn2p and Rpt2p, were shown to possess functional nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequences, and because the simultaneous deletion of these sequences is lethal, it was suggested that the nuclear import of the base probably depends on its own NLS(s) (Wendler et al., 2004). No component of the lid was yet proved to be responsible for the nuclear import of the lid. Our results suggest that Rpn3p, Rpn7p, and Rpn12, each of which is localized into nucleus by itself, may serve for the nuclear import of the lid (Figure 7D).

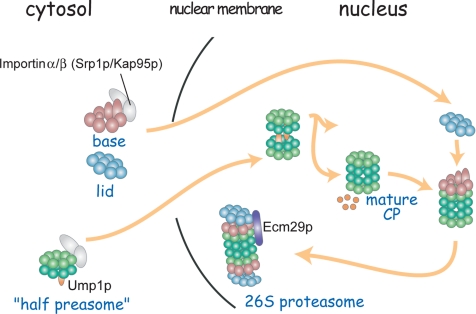

We have shown in this study that the lid, a substructure of the 26S proteasome, can be formed and imported into the nucleus independently of the other subcomplexes of the 26S proteasome. Together with the result that a base–CP complex is formed in the analyzed lid mutants, we propose the following scenario of the assembling pathway of the 26S proteasome (Figure 9). The half-proteasome as well as base and the lid are formed independently in the cytosol, and they are imported into the nucleus. Then, the base binds the mature CP, and finally the lid binds the base–CP complex to form a mature 26S proteasome. In the course of the formation of the lid, Rpn5p, together with its interacting components forms the core of the lid, into which Rpn6p then the rest of the components are sequentially incorporated to become a complete lid. It should be noted that the scenario of the assembly pathway described above had been drawn using mutants, and there might be a different pathway in wild-type cells. In wild-type cells, the assembly processes are probably too rapid to be detected biochemically, because the apparent intermediates of the 26S proteasome such as the base–CP complex, lidrpn6-1 and lidrpn7-3 existed in lid mutants under the restrictive condition (Isono et al., 2004, 2005) cannot be detected.

Figure 9.

Model for the assembling process of the 26S proteasome in budding yeast. The base and the lid are made in the cytosol and are imported into the nucleus independently. On the dimerization of half-proteasomes into a mature CP, the base binds the CP. The immediate binding of the lid to the base–CP complex stabilizes the whole complex. Additional interacting proteins are bound to the 26S proteasome.

This consideration casts another question as to whether there are any factors that facilitate or regulate the interaction between the base, lid and CP. It should be noted that a recent report with mammalian cells has shown that a protein interacting with the ATPase subunits of the base, named PAAF1, inhibits the binding of the RP and the CP (Park et al., 2005). Whether external factors are involved in the formation of the lid and the base is also a question that remains to be answered.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Daniel Finley (Harvard University, Boston, MA) for the anti-Rpn8p antibody, Dr. Jussi Jantti (University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland) for the anti-Sem1p (Rpn15p) antibody, and Dr. Roger Tsien (University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA) for the mRFP1 plasmid. We are grateful to Dr. Cordula Enenkel (Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany) for valuable suggestions and advice, Drs. Satoshi Yoshida (Harvard University, Boston, MA) and Takashi Itoh (RIKEN, Saitama, Japan) for technical advice, and the members of the Laboratory of Genetics for discussions and comments. Thanks are also due to Drs. Yoshibumi Komeda and Ichiro Terashima (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan) for generously letting us use the laboratory space and to Naoko Saito for earlier contribution to this work. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (to A.T.) and by a grant-in-aid from the Japan Society for Promotion of Young Scientists (to E.I.).

Abbreviations used:

- CBB

Coomassie brilliant blue

- CP

core particle

- FRAP

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MCA

methycoumaryl-7-amide

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- PCI

proteasome/COP9/Initiation factor

- mRFP

monomeric red fluorescent protein

- RP

regulatory particle

- Rpn

regulatory particle non-ATPase

- Rpt

regulatory particle triple A ATPase

- Suc-LLVY

succinyl-leucyl-leucyl-valyl-tyrosyl

- Ub

ubiquitin

- UFD

ubiquitin fusion degradation

- UPS

ubiquitin–proteasome system.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0635) on November 29, 2006.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

REFERENCES

- Bachmair A., Finley D., Varshavsky A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 1986;234:179–186. doi: 10.1126/science.3018930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk D., Dawson D., Stearns T. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell R. C., Joyce G. F. Randomization of genes by PCR mutagenesis. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;2:28–33. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R. E., Tour O., Palmer A. E., Steinbach P. A., Baird G. S., Zacharias D. A., Tsien R. Y. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Hochstrasser M. Autocatalytic subunit processing couples active site formation in the 20S proteasome to completion of assembly. Cell. 1996;86:961–972. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope G. A., Suh G. S., Aravind L., Schwarz S. E., Zipursky S. L., Koonin E. V., Deshaies R. J. Role of predicted metalloprotease motif of Jab1/Csn5 in cleavage of Nedd8 from Cul1. Science. 2002;298:608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1075901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack B. P., Valdivia R. H., Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser S., Chandler-Militello D., Muller B., Hanna J., Finley D. Rad23 and Rpn10 serve as alternative ubiquitin receptors for the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:26817–26822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enenkel C., Lehmann A., Kloetzel P. M. GFP-labelling of 26S proteasomes in living yeast: insight into proteasomal functions at the nuclear envelope/rough ER. Mol. Biol. Rep. 1999;26:131–135. doi: 10.1023/a:1006973803960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehlker M., Wendler P., Lehmann A., Enenkel C. Blm3 is part of nascent proteasomes and is involved in a late stage of nuclear proteasome assembly. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:959–963. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D. Unified nomenclature for subunits of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteasome regulatory particle. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:244–245. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H., Reis N., Lee Y., Glickman M. H., Vierstra R. D. Subunit interaction maps for the regulatory particle of the 26S proteasome and the COP9 signalosome. EMBO J. 2001;20:7096–7107. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi M., Li X., Velichutina I., Hochstrasser M., Kobayashi H. Sem1, the yeast ortholog of a human BRCA2-binding protein, is a component of the proteasome regulatory particle that enhances proteasome stability. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:6447–6454. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman M. H., Rubin D. M., Coux O., Wefes I., Pfeifer G., Cjeka Z., Baumeister W., Fried V. A., Finley D., et al. A subcomplex of the proteasome regulatory particle required for ubiquitin-conjugate degradation and related to the COP9-signalosome and eIF3. Cell. 1998a;94:615–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman M. H., Rubin D. M., Fried V. A., Finley D. The regulatory particle of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteasome. Mol. Cell Biol. 1998b;18:3149–3162. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterman A., Glickman M. H. Complementary roles for Rpn11 and Ubp6 in deubiquitination and proteolysis by the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:1729–1738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano Y., Hendil K. B., Yashiroda H., Iemura S., Nagane R., Hioki Y., Natsume T., Tanaka K., Murata S. A heterodimeric complex that promotes the assembly of mammalian 20S proteasomes. Nature. 2005;437:1381–1385. doi: 10.1038/nature04106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoepfner D., Brachat A., Philippsen P. Time-lapse video microscopy analysis reveals astral microtubule detachment in the yeast spindle pole mutant cnm67. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:1197–1211. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.4.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K., Bucher P. The PCI domain: a common theme in three multiprotein complexes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:204–205. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isono E., Saeki Y., Yokosawa H., Toh-e A. Rpn7 Is required for the structural integrity of the 26 S proteasome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:27168–27176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isono E., Saito N., Kamata N., Saeki Y., Toh E. A., et al. Functional analysis of Rpn6p, a lid component of the 26 S proteasome, using temperature-sensitive rpn6 mutants of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:6537–6547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett D. S., Hanna J., Borodovsky A., Crosas B., Schmidt M., Baker R. T., Walz T., Ploegh H., Finley D. Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:495–507. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A., Janek K., Braun B., Kloetzel P. M., Enenkel C. 20 S proteasomes are imported as precursor complexes into the nucleus of yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:401–413. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maytal-Kivity V., Reis N., Hofmann K., Glickman M. H. MPN+, a putative catalytic motif found in a subset of MPN domain proteins from eukaryotes and prokaryotes, is critical for Rpn11 function. BMC Biochem. 2002;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Hwang Y. P., Lee J. S., Seo S. H., Yoon S. K., Yoon J. B. Proteasomal ATPase-associated factor 1 negatively regulates proteasome activity by interacting with proteasomal ATPases. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:3842–3853. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3842-3853.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos P. C., Hockendorff J., Johnson E. S., Varshavsky A., Dohmen R. J. Ump1p is required for proper maturation of the 20S proteasome and becomes its substrate upon completion of the assembly. Cell. 1998;92:489–499. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80942-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki Y., Isono E., Toh-e A. Preparation of ubiquitinated substrates by the PY motif-insertion method for monitoring 26S proteasome activity. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:215–227. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki Y., Saitoh A., Toh-e A., Yokosawa H. Ubiquitin-like proteins and Rpn10 play cooperative roles in ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;293:986–992. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T., Toh-e A., Kikuchi Y. Yeast Krr1p physically and functionally interacts with a novel essential Kri1p, and both proteins are required for 40S ribosome biogenesis in the nucleolus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:7971–7979. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7971-7979.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M., Haas W., Crosas B., Santamaria P. G., Gygi S. P., Walz T., Finley D. The HEAT repeat protein Blm10 regulates the yeast proteasome by capping the core particle. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:294–303. doi: 10.1038/nsmb914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A. L., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and pathogenesis of human diseases. Annu. Rev. Med. 1999;50:57–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon M., Taverner T., Ambroggio X. I., Deshaies R. J., and Robinson C. V. Structural organization of the 19S proteasome lid: insights from MS of intact complexes. PLoS Biol. 2006;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F., Fink G. R., Hicks J. B. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1986. pp. 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone T., Saeki Y., Toh-e A., Yokosawa H. Sem1p is a novel subunit of the 26 S proteasome from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:28807–28816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabb M. M., Tongaonkar P., Vu L., Nomura M. Evidence for separable functions of Srp1p, the yeast homolog of importin alpha (Karyopherin alpha): role for Srp1p and Sts1p in protein degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:6062–6073. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.6062-6073.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K., Yanagida M. Regulation of nuclear proteasome by Rhp6/Ubc2 through ubiquitination and destruction of the sensor and anchor Cut8. Cell. 2005;122:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebe H., Yanagida M. Cut8, essential for anaphase, controls localization of 26S proteasome, facilitating destruction of cyclin and Cut2. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh-e A., Oguchi T. An improved integration replacement/disruption method for mutagenesis of yeast essential genes. Genes Genet. Syst. 2000;75:33–39. doi: 10.1266/ggs.75.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nocker S., Sadis S., Rubin D. M., Glickman M., Fu H., Coux O., Wefes I., Finley D., Vierstra R. D. The multiubiquitin-chain-binding protein Mcb1 is a component of the 26S proteasome in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and plays a nonessential, substrate-specific role in protein turnover. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:6020–6028. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R., Aravind L., Oania R., McDonald W. H., Yates J. R., 3rd, Koonin E. V., Deshaies R. J. Role of Rpn11 metalloprotease in deubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome. Science. 2002;298:611–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1075898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler P., Lehmann A., Janek K., Baumgart S., Enenkel C. The bipartite nuclear localization sequence of Rpn2 is required for nuclear import of proteasomal base complexes via karyopherin αβ and proteasome functions. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37751–37762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson C. R., Wallace M., Morphew M., Perry P., Allshire R., Javerzat J. P., McIntosh J. R., Gordon C. Localization of the 26S proteasome during mitosis and meiosis in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1998;17:6465–6476. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao T., Cohen R. E. A cryptic protease couples deubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. Nature. 2002;419:403–407. doi: 10.1038/nature01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen H. C., Espiritu C., Chang E. C. Rpn5 is a conserved proteasome subunit and required for proper proteasome localization and assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2003a;278:30669–30676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen H. C., Gordon C., Chang E. C. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Int6 and Ras homologs regulate cell division and mitotic fidelity via the proteasome. Cell. 2003b;112:207–217. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota K. CDNA cloning of p112, the largest regulatory subunit of the human 26s proteasome, and functional analysis of its yeast homologue, sen3p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:853–870. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.6.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.