Abstract

The neuregulins (NRGs) play important roles in animal physiology, and their disregulation has been linked to diseases such as cancer or schizophrenia. The NRGs may be produced as transmembrane proteins (proNRGs), even though they lack an N-terminal signal sequence. This raises the question of how NRGs are sorted to the plasma membrane. It is also unclear whether in their transmembrane state, the NRGs are biologically active. During studies aimed at solving these questions, we found that deletion of the extracellular juxtamembrane region termed the linker, decreased cell surface exposure of the mutant proNRGΔLinker, and caused its entrapment at the cis-Golgi. We also found that cell surface–exposed transmembrane NRG forms retain biological activity. Thus, a mutant whose cleavage is impaired but is correctly sorted to the plasma membrane activated ErbB receptors in trans and also stimulated proliferation. Because the linker is implicated in surface sorting and the regulation of the cleavage of transmembrane NRGs, our data indicate that this region exerts multiple important roles in the physiology of NRGs.

INTRODUCTION

The neuregulins (NRGs) are a group of polypeptide factors that participate in several physiological processes such as heart and peripheral nervous system development (Meyer and Birchmeier, 1995; Britsch et al., 1998). Structurally, and because of the presence of an epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like module, these factors have been integrated into the EGF family of transmembrane ligands, which also includes EGF, transforming growth factor-α (TGFα), amphiregulin, heparin-binding EGF (HB-EGF), betacellulin, epiregulin, and epigen (Massagué and Pandiella, 1993; Harris et al., 2003). These ligands are synthesized as membrane-bound forms that can be solubilized by the action of cell surface proteases, termed secretases (Blobel, 2005).

Four different NRG genes have been identified (Holmes et al., 1992; Peles et al., 1992; Busfield et al., 1997; Carraway et al., 1997; Chang et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1997; Harari et al., 1999). Complex alternative splicing of mRNAs produced by these genes generates at least 15 different NRG isoforms (Falls, 2003). Depending on the sequences found at their N-terminal region, these isoforms have been grouped into three different NRG types (Meyer et al., 1997; Falls, 2003). Type I isoforms contain an N-terminal Ig-like domain; type II contain an N-terminal kringle-like domain, followed by the Ig-like domain; and type III contain an N-terminal hydrophobic domain within a cysteine-rich region (Meyer et al., 1997; Falls, 2003). These divergent N-terminal regions are followed by the EGF-like domain. In addition, the NRGs may contain a linker (that includes a site for proteolytic attack by cell surface secretases), an internal hydrophobic sequence, and a C-terminal tail.

Type I NRGs are synthesized as larger transmembrane molecules referred to as proNRGs, in homology to the precursor forms of other membrane-anchored growth factors of the EGF family (Wen et al., 1994). Interestingly, and in contrast to the other EGF family factors, transmembrane type I proNRGs lack an N-terminal signal sequence. This fact raises the question of which domains of proNRGs are involved in their membrane anchoring and proper cell surface targeting.

The expression of type I NRGs as membrane bound factors also raises the interesting question of whether these factors are active in their membrane-anchored form. Although soluble forms of the EGF family factors have demonstrated biological activity, the capacity of membrane-anchored forms to be functional is still controversial (Blobel, 2005). Thus, several in vitro studies indicated that membrane-bound factors of the EGF family, including proTGFα (Brachmann et al., 1989; Wong et al., 1989; Anklesaria et al., 1990; Baselga et al., 1996), proEGF, proNRG, or proHB-EGF, retain biological activity in their transmembrane forms (Dobashi and Stern, 1991; Higashiyama et al., 1995; Aguilar and Slamon, 2001). Furthermore, membrane-anchored forms of proTGFα may activate the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) more efficiently than soluble forms of this growth factor (Yang et al., 2000). However, results obtained using other experimental models indicate that shedding is required for the action of membrane-bound factors. Thus, metalloprotease inhibitors that prevent cleavage of membrane-anchored factors blocked HB-EGF–mediated transactivation of the EGF receptor (Prenzel et al., 1999) or reduced proliferation and migration of breast epithelial cells expressing proTGFα and proamphiregulin (Dong et al., 1999). Furthermore, cells bearing inactive forms of TACE, a secretase that cleaves proTGFα (Peschon et al., 1998; Sunnarborg et al., 2002; Juanes et al., 2005), are unable to activate the EGFR in vitro, and fail to generate tumors in nude mice (Borrell-Pages et al., 2003). In addition, genetic data in flies (Golembo et al., 1996) and mice (Yamazaki et al., 2003) have suggested that release of membrane-anchored factors is required for proper animal development. Therefore, shedding of membrane-anchored growth factors may represent a rate-limiting step in their biological action, at least when required at a distance from their site of production.

The domain of proNRGs where shedding occurs is the linker. This region ranges from 44 to 18 amino acids, depending on the proNRG isoform (Fischbach and Rosen, 1997; Falls, 2003). Characterization of the cleavage sites in the proNRGα2c isoform indicated that cleavage occurs at the Met-Lys-Val (MKV) microdomain within the linker region (Lu et al., 1995). Deletion of the MKV sequence resulted in resistance to ectodomain shedding of the proNRGα2c (Montero et al., 2000). These studies accompany others (Wong et al., 1989; Hinkle et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2004) in confirming the importance of the linker region in the regulation of the cleavage efficiency of membrane-anchored growth factors of the EGF family.

The fact that type I proNRGs are cell surface proteins but lack an N-terminal signal sequence attracted us to investigate the domains implicated in the membrane anchoring and cell surface delivery of proNRGs. In addition, we wanted to explore whether transmembrane proNRGs can be biologically active. Here we report that the extracellular juxtamembrane linker is required for efficient sorting of proNRGα2c to the plasma membrane. In addition, we demonstrate that membrane-bound proNRGα2c retains the capability to induce cell proliferation. Because the linker appears to be required for proper surface sorting, for the regulation of the cleavage of transmembrane NRGs, and for retention of the biological activity, our data indicate that this region plays multiple important roles in the physiology of NRGs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Immunochemicals

Culture media, sera, and G418 were purchased from GIBCO BRL (Gaithersburg, MD). Protein A-Sepharose was from Amersham-Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ). Immobilon-P membranes were from Millipore (Bedford, MA). DAPI, brefeldin A, proteinase K, Protein A-HRP, tunicamycin, and doxycycline were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). BB3103 was generously provided by British Biotech (Cowley, Oxford, United Kingdom). NHS-LC-biotin was from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Mitotracker was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Endoglycosidase H and N-glycosidase were from Roche Biochemicals (Indianapolis, IN). Other generic chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical, Roche Biochemicals, or Merck (Rahway, NJ).

The mouse monoclonal anti-PDI was from Stressgen (San Diego, CA). The anti-actin antibody was from Sigma. Anti-HER3, anti-HER4 and anti-phosphotyrosine were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti-pY1248, anti-pY1221/1222 and anti-pY877 that recognize phosphorylated ErbB2, and anti-pAkt were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). The anti-pY1139 was from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA). The antibodies to GM130 and p230 were from BD Transduction (Lexington, KY). The Ab3 anti-ErbB2 antibody used for Western blotting was from Oncogene Science (Manhasset, NY). The monoclonal anti-HER2 ectodomain antibody herceptin, and soluble recombinant NRG were generously provided by Dr. Mark X. Sliwkowski (Genentech, San Francisco, CA). The RKII anti-EGFR antibody was generously provided by Dr. Joseph Schlessinger. The Cy3- or Cy2-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). HRP conjugates of anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Cambridge, MA).

Anti-proNRGα2c was raised against the sequence NH2-CETPDSYRSDPHSER-COOH that corresponds to the 15 COOH-terminal residues of rat NRGα2c (Montero et al., 2000). For the generation of the anti-rat-NRG antibodies we immunized rabbits with a GST fusion protein that included amino acids 19-181 of the proNRGα2c, which corresponds to the ectodomain of this protein.

Metabolic Labeling

Cells in 60-mm dishes were washed twice for 20 min each with methionine- and cysteine-free DMEM and then were incubated in the same medium with 200 μCi/ml of a mixture of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (Redivue Promix L-35S in vitro labeling mix, from Amersham). Incubations with the radioactive medium proceeded for the times indicated in the figures, and then medium was replaced by fresh medium. Cells were lysed and then immunoprecipitated with the anti-proNRG antibody. Samples were run in 8% SDS-PAGE gels that were dried and exposed to a autoradiographic film or to a phosphorimager screen for quantitative analyses.

Cell Culture and Transfections

The conditions for the culture of MCF7 and 293 cells have been described (Esparís-Ogando et al., 1999). Transfections in MCF7 or 293 cells were performed by calcium phosphate, and clones were selected by G418. Single clones were analyzed for their content of proNRG forms by Western blotting with the anti-proNRG antibody. The proNRGα2c-TetOff and the TACEΔZn/ΔZn-NRGα2c cells have been described in Yuste et al. (2005), and Montero et al. (2000).

Plasmids and Construction of Mutants

The different forms of rat NRGα2c were subcloned into KpnI/NotI sites of the pCDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The different deletions in the juxtamembrane region of proNRGα2c were generated by site directed mutagenesis (MKV mutant) or PCR (rest of mutants) as described (Montero et al., 2000). The Ig-like domain deletion (amino acids 19–177) was created by digestion with BamHI. Mutants of proNRGα2c were verified by automated sequencing.

For the swapping of the linker of proNRGα2c for a corresponding sequence of the juxtamembrane region of the EGFR or ErbB2, these regions were amplified using the following oligonucleotides: forward egfr linker 5′-CCGGAATTCTGCACTGGGCCAGGT-3′, reverse egfr linker 5′-CCGGAATTCGGACGGGATCTTAGG-3′; forward erbb2 linker 5′-CCGGAATTCGTGGACCTGGATGAC-3′, reverse erbb2 linker 5′-CCGGAATTCCGTCAGAGGGCTGGC-3′. PCR amplification using these primers generated fragments that were digested with EcoRI and subcloned into pCDNA3-proNRGα2c in which the linker was deleted by PCR, at the time that an EcoRI site was placed to allow the subcloning of the linkers of EGFR and ErbB2.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 1 μM pepstatin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate). After scraping the cells from the dishes, samples were centrifuged at 10000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and supernatants were transferred to new tubes with the corresponding antibody and protein A-Sepharose. Immunoprecipitations were performed at 4°C for at least 2 h, and the immune complexes were recovered by a short centrifugation followed by three washes with 1 ml of cold lysis buffer. Samples were then boiled in electrophoresis sample buffer and loaded in SDS-PAGE gels. The rest of the Western blotting procedure was as described (Cabrera et al., 1996).

For cell surface immunoprecipitation, cells in 100-mm dishes were washed twice with Krebs-Ringer-HEPES buffer (KRH; Cabrera et al., 1996) and then incubated for 2 h at 4°C with 4 μl of anti-NRG antibody in 1 ml of KRH. Monolayers were washed twice with PBS and lysed. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and supernatants transferred to new tubes with protein A-Sepharose.

Proteinase Protection Experiments, Cell Surface Biotinylation, and Cell Fractionation

Proteinase K protection experiments were carried out as described (Cabrera et al., 1996). Briefly, cells were washed once with KRH buffer and then incubated in this buffer supplemented with 200 μg/ml proteinase K for 30 min. Cells were then washed three times with PBS containing 2 mM PMSF and lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer with protease inhibitors. Analyses of the effect of proteinase K on the different mutants and wild-type proNRGα2c were carried out by Western blotting using anti-proNRG.

For cell surface biotinylation, cells were washed twice with ice-cold KRH and then incubated with NHS-LC-biotin (100 μg/ml) for 2 h at 4°C. Cells were washed again with KRH and then incubated with KRH containing 10 mM glycine for 15 min at 4°C. Cell monolayers were washed and lysed, and the lysates were precipitated with streptavidin agarose. Samples were run in 12% SDS-PAGE gels and analyzed by Western blotting with the anti-proNRG antiserum.

For the cell fractionation experiments (Massague, 1983), cells from 10 100-mm dishes (90% confluent) were washed with PBS and detached by incubation for 10 min at 37°C with 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 10 mM Tris, pH 7.0. The cell suspension was homogenized on ice with a tight-fitting Dounce homogenizer. This homogenate was centrifuged at 4000 × g for 10 min, and the resulting pellet was rehomogenized and centrifuged at the same speed. The supernatants from these two centrifugation steps were pooled and centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was taken as the cytosolic fraction. The resulting pellet was resuspended in homogenization buffer, layered on top of a 36% (wt/wt) sucrose solution, and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min. The fraction of membranous material at the 36% interface was collected, sedimented at 30,000 × g for 30 min, and resuspended in lysis buffer. This fraction corresponds to the plasma membrane. The pellet obtained by centrifugation throughout the sucrose cushion was taken as the microsomal nonplasma membrane fraction.

In Vitro Deglycosylation Experiments

Protein precipitates were solubilized by boiling for 5 min in 10 μl of 0.25% (wt/vol) SDS, and 0.1 M β-2-mercaptoethanol. Then, 4 mU of endoglycosidase H and 0.5 μg of each of the protease inhibitors were added in 20 μl of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.8) and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Digestions were terminated by adding an equal volume of Laemmli sample buffer and heating for 5 min at 100°C. The digestion products were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting as above.

Cell Proliferation

Conditions for the analysis of the proliferation of MCF7 cells and derived clones have been reported (Esparis-Ogando et al., 2002). Cells were plated at 20,000 cells/well and cultured overnight in DMEM + 10% FBS. The next day (day 1 of culture) cells were shifted to serum-free media, and an MTT assay was performed and considered the starting point. MTT uptakes were measured at the times indicated in the figure legends.

Immunofluorescence Experiments

Cells cultured on glass coverslips were washed with PBS and fixed in 2% p-formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, followed by two rinses in PBS. To follow mitochondrial staining, 100 nM of Mitotracker Red (Molecular Probes) was added for 20 min before fixing with p-formaldehyde. Monolayers were then washed twice, for 10 min each time, with PBS supplemented with 0.1% (final concentration) Triton X-100 and then blocked in PBS with 0.2% BSA for 20 min at room temperature. The immunofluorescence protocol has been described (Esparis-Ogando et al., 2002).

Quantitative Estimation of proNRG Forms

Quantitation of the different proNRG in Western blots was performed by using the NIH Image 1.61 software. To graphically represent the values of each band (80 and 70–72-kDa forms for proNRGα2c, the intensity of each band was measured densitometrically. Then the sum of the bands was taken as 100%, and the percentage intensity of each band with respect to the total of that sample, or the control lane was calculated and plotted. Data show the mean ± SD for three different experiments.

RESULTS

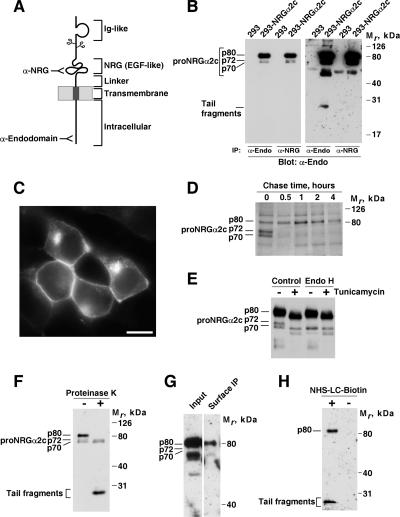

Different Subcellular Distribution of proNRGα2c Forms

This study was initiated with the purpose of evaluating the domains of proNRG that are required for efficient sorting to the plasma membrane. As a model we used proNRGα2c, a member of the type I subfamily of NRGs (Wen et al., 1994; Falls, 2003). The extracellular region of this NRG contains an N-terminal Ig-like domain followed by an EGF-like module, the linker region, and the transmembrane and intracellular domains (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Forms and subcellular distribution of proNRGα2c. (A) Schematic representation of the different domains of proNRGα2c. The sites recognized by the antibodies are shown. (B) Expression of proNRGα2c in 293 cells. Cells transfected with the cDNA coding for proNRGα2c (293-NRGα2c) were lysed, and samples immunoprecipitated with anti-endodomain or anti-NRG antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with the anti-endodomain antibody. The right panel is an overexposure of the left panel. The position of the Mr markers is shown at the right. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of the subcellular distribution of proNRGα2c. 293-NRGα2c cells were plated on coverslips and stained with the anti-proNRG antibody. Bar, 20 μm. (D) Pulse-chase experiment of proNRGα2c. 293-NRGα2c cells were metabolically labeled for 30 min and then chased for the indicated times. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-proNRG antibody, and the precipitates were analyzed in an 8% SDS-PAGE gel followed by autoradiography. (E) Endoglycosidase analysis of proNRGα2c. 293-NRGα2c cells were treated with or without tunicamycin (10 μg/ml) overnight, lysed, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with the anti-proNRG antibody. Where indicated the immunocomplexes were digested with endoglycosidase H and analyzed in 8% SDS-PAGE gels. The blot was probed with the proNRG antibody. (F) Protease protection experiments of proNRGα2c. Cells were treated with proteinase K, lysed, and subjected to immunoprecipitation and Western blotting with the anti-proNRG. (G) Cell surface immunoprecipitation of proNRGα2c. 293-NRGα2c cells were incubated with the anti-NRG antibody and lysed, and surface-bound antibody was precipitated with protein A-Sepharose. The Western blot was probed with the anti-proNRG antibody. (H) Cell surface biotinylation of proNRGα2c. Cells were incubated with or without NHS-LC-biotin, and lysates were precipitated with streptavidin agarose. The blot was probed with the anti-proNRG antibody.

We analyzed the molecular forms and subcellular location of proNRGα2c using 293 cells transfected with a cDNA coding for rat proNRGα2c. In 293-NRGα2c cells, Western blotting with the anti-proNRG antibody, that recognizes the intracellular C-terminus of proNRGα2c (Montero et al., 2000), which identified a major band that migrated with an apparent Mr of 80 kDa (p80), together with two less abundant bands with apparent Mr of 70 and 72 kDa (p70 and p72, respectively; Figure 1, B and D). These latter two bands migrated very closely and were sometimes difficult to differentiate from each other. The three bands corresponded to proNRGα2c as indicated by the failure of the antibody to recognize analogous bands in parental 293 cells (Figure 1B). On longer exposure times of the blots, the anti-endodomain antibody also recognized lower Mr forms (Figure 1B, right panel). These forms correspond to cell-bound tail fragments generated upon cleavage of proNRGα2c at the extracellular domain (Montero et al., 2000). The 80-, 70-, and 72-kDa forms contained the EGF-like NRG domain, as indicated by their reactivity with an antibody raised to a GST fusion protein that contained the NRG domain of proNRGα2c (Figure 1B). This anti-NRG antibody, however, failed to immunoprecipitate the lower Mr tail fragments, indicating that these forms were devoid of the EGF-like domain of NRG (Figure 1B, right panel). Analogous results were obtained in CHO cells expressing proNRGα2c (data not shown; Montero et al., 2000).

Immunofluorescence experiments in 293-NRGα2c cells stained with the anti-proNRGα2c antibody indicated that proNRGα2c accumulated at two different sites: the cell surface and an intracellular perinuclear site (Figure 1C). Analogous results were obtained by analyzing the distribution of proNRGα2c-GFP in which the C-terminus of proNRGα2c was fused to GFP (data not shown). The presence of multiple proNRGα2c forms, together with the immunofluorescence data raised the possibility that different proNRGα2c forms could be located at distinct cellular sites. To explore this possibility, we performed several types of experiments. As an initial step, we followed the biosynthesis of p80, p72, and p70 by pulse-chase analyses. Cells were metabolically labeled for 30 min with 35S-amino acids and then chased for different times. At the earliest time point analyzed, p70 and p72 were clearly labeled (Figure 1D). These bands were then rapidly chased to the 80-kDa form, whose amount reached a maximum by 1 h of chase. At this latter time point the amount of p70 and p72 was already very low. These data indicate that p70 and p72 may represent immature proNRGα2c forms that chase into an 80-kDa more mature form.

To gain further insights into the nature of the p80, p72, and p70 forms, we explored their glycosylation status. Treatments that prevented N-linked glycosylation in vivo (tunicamycin, Figure 1E) or enzymatically removed N-linked sugars in vitro (N-glycosidase; data not shown) provoked disappearance of the p72 form and a decrease in the apparent Mr of the p80 form. We also used endoglycosidase H (Endo H), which has been used to study the topological location of glycosylated proteins while en route to the plasma membrane. This glycosidase is active on high mannose oligosaccharides present in proteins in their early steps of N-linked maturation. However, when the N-glycosylated protein moves through the Golgi, the trimming of two mannoses by Golgi mannosidase II, together with the addition of other sugars, generates a complex oligosaccharide that is resistant to the action of Endo H. Enzymatic deglycosylation with Endo H also caused disappearance of p72. However, the p80 form was resistant to Endo H. The different sensitivity of p72 and p80 was taken as an indication that distinct proNRGα2c forms resided at different subcellular sites. Treatment with Endo H did not apparently affect the p70 form, indicating that this form did not contain N-linker sugars or had already moved to a subcellular compartment where additional maturation of sugar chains created a complex glycoprotein resistant to Endo H.

To investigate whether p80, p72, and 70 kDa forms were exposed at the plasma membrane, we first analyzed their sensitivity to protease K. Exposure of intact cells to the protease caused disappearance of p80, but did not change the amount of p72 or p70 (Figure 1F). As expected, protease K treatment caused accumulation of the cell-associated tail fragments that result from the degradation of the ectodomain of proNRGα2c. In cell surface immunoprecipitation experiments, the anti-NRG antibody precipitated the 80-kDa form, further supporting that this form was exposed at the cell surface (Figure 1G). That the 80-kDa form was the only proNRGα2c form exposed at the plasma membrane was further confirmed by surface biotinylation experiments (Figure 1H).

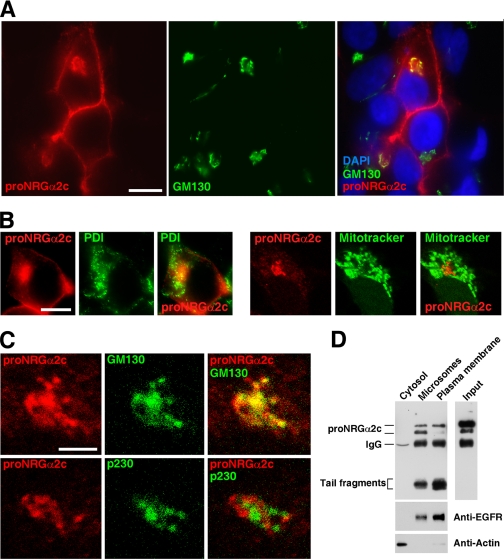

Colocalization experiments using antibodies to different intracellular compartments indicated that intracellular proNRGα2c was mainly present in the Golgi, because the proNRGα2c staining colocalized with the cis-Golgi marker GM130 (Figure 2A). In contrast, little proNRGα2c immunoreactivity colocalized with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) marker PDI and none with the mitochondrial stain mitotracker (Figure 2B). Staining with the anti-proNRG endodomain antibody was coincident with that of GM130 (Figure 2C), but not with the trans-Golgi marker p230, indicating that the intracellular accumulation observed in these cells corresponds to proNRGα2c that is present at the cis-Golgi.

Figure 2.

Intracellular proNRGα2c colocalizes with Golgi markers. (A) Colocalization of proNRG with the Golgi marker GM130. Immunofluorescence was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Bar, 20 μm. (B) Immunofluorescence images showing the distribution of proNRGα2c, PDI, and the mitochondrial stain Mitotracker. Bar, 20 μm. (C) Colocalization of proNRG with the cis-Golgi marker GM130 but not with the trans-Golgi marker p230. Cells treated with brefeldin A were analyzed by immunofluorescence with anti-GM130, anti-p230, and anti-proNRG antibodies. Bar, 5 μm. (D) Cell fractionation experiments of proNRGα2c. Cells were fractionated as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed for proNRG, EGFR, and actin by Western blotting.

In cell fractionation experiments the plasma membrane–enriched fraction mainly contained the p80 form, together with the lower Mr cell-associated tail fragments (Figure 2D). Little amounts of p70 and p72 kDa were detected. The rest of the microsomal fraction mainly contained the p70 and p72 kDa forms, together with a smaller amount of the lower Mr cell-associated fragments. Also, some p80 was present, as well as the 170-kDa EGFR, likely indicating that the microsomal fraction contained a small amount of plasma membrane–derived microsomes (Figure 2D).

Taken together, these data indicate that proNRGα2c is expressed as several Mr forms, one of 80 kDa that is exposed at the cell surface and less abundant forms of 70 and 72 kDa that are located intracellularly, mainly at the cis-Golgi apparatus.

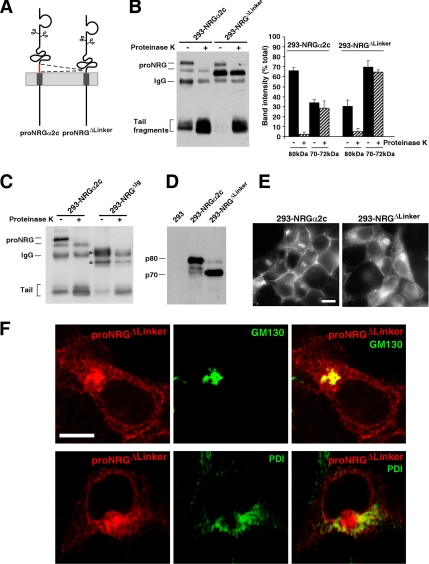

Deletion of the Linker Causes Intracellular Entrapment of pro-NRGα2c

We searched for domains that regulate proNRGα2c sorting by performing deletions in various regions of proNRGα2c. In 293 cells expressing a deletion of the linker (proNRGΔLinker mutant; Figure 3A), we observed that the pattern of the proNRG forms was inverted with respect to wild-type proNRGα2c (Figure 3B). Thus, although in the wild type the major proNRGα2c form corresponded to p80, in the proNRGΔLinker mutant the most abundant form corresponded to a band that migrated in the 70-kDa region. This inverted pattern was also confirmed by metabolic labeling of 293 cells expressing wild-type or the proNRGΔLinker mutant (data not shown). Because of the deletion of the linker, the Mr of the proNRGΔLinker forms was slightly smaller than that of the wild-type forms. However, for better understanding, we refer to them as p80 and p70, for the slower and faster migrating forms, respectively. Protease protection experiments indicated that the faster migrating form of proNRGΔLinker was largely insensitive to proteinase K, whereas the slower migrating form disappeared in cells treated with the protease (Figure 3B). Cell fractionation experiments performed in 293-NRGΔLinker cells confirmed that most of the faster migrating form of proNRGΔLinker was retained within the microsomal nonplasma membrane fraction (data not shown). We analyzed whether deletion of other extracellular regions could also provoke a similar accumulation of the faster-migrating forms. To this end, we performed a deletion of the entire Ig-like domain of proNRGα2c. As shown in Figure 3C, deletion of this region resulted in a significantly faster electrophoretic mobility of the proNRGΔIg form. However, this form resembled wild-type proNRGα2c in terms of relative abundance of the mature and immature forms and of sensitivity to protease K. We also evaluated whether shortening of the linker could provoke gross misfolding of the EGF-like domain by analyzing the immunoreactivity of the core NRG domain with the anti-NRG antibody, which recognizes native NRG and can block the biological activity of soluble NRG (R. Rodríguez-Barrueco and A. Pandiella, unpublished observations). This antibody precipitated both wild-type and proNRGΔLinker forms in an analogous manner (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

The linker region of proNRGα2c facilitates transit through the Golgi. (A) Schematic representation of the deletion of the linker of proNRGα2c. (B) Protease protection experiments of the proNRGΔLinker. Cells were treated with protease K and lysed, and the extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation and Western blotting with the anti-proNRG antibody. The histogram shown is a quantitation of the intensity of the bands of 80 and 70–72 kDa. The percentage is calculated with respect to the total signal of the control lane. The results represent the mean ± SD of three different experiments. (C) Expression of proNRGΔIg in 293 cells and its sensitivity to protease K. The position of the mature and immature forms of this mutant are indicated by asterisks. (D) Immunoprecipitation of proNRGα2c or proNRGΔLinker with the anti-NRG antibody, followed by Western blotting with the anti-NRG antibody. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis of the subcellular distribution of proNRGα2c and proNRGΔLinker mutant. Bar, 20 μm. (F) Colocalization of the proNRGΔLinker mutant with the Golgi marker GM130. Monolayers were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with anti-proNRG, anti-GM130, or anti-PDI antibodies. Images were captured using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. Bar, 20 μm.

Immunofluorescence experiments indicated differences in the subcellular distributions of the wild-type and the proNRGΔLinker mutant (Figure 3E). As expected from the protease K protection experiments, the plasma membrane staining of the proNRGΔLinker mutant was weak, whereas the intracellular staining was substantially increased with respect to wild-type proNRGα2c (Figure 3E). Most of the proNRGΔLinker colocalized with the GM130 Golgi marker (Figure 3F), even though a small amount also appeared to codistribute with PDI.

To biochemically evaluate the cellular site where proNRGΔLinker was trapped, we performed several types of experiments. First, we analyzed whether defects in the biosynthesis of proNRGΔLinker could explain its intracellular retention. Cells were metabolically labeled for 20 min and then chased for different times. As shown above, wild-type proNRGα2c was initially present as two forms of 70 and 72 kDa that were rapidly chased into the 80-kDa form (Figure 4A). In 293-NRGΔLinker cells the bands in the 70-kDa region chased very poorly into the mature form. In these cells, the early biosynthetic steps included two diffuse bands that were chased to another band of intermediate Mr (arrow in Figure 4A). The presence of the latter was obvious at 40 min of chase and lasted for the entire duration of the experiment. Quantitative analyses supported that the faster migrating forms of proNRGα2c chased into the mature 80-kDa form, whereas the faster migrating form of proNRGΔLinker inefficiently chased into the mature form (Figure 4A, bottom graphics).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the linker region of proNRGα2c. (A) Pulse-chase analyses of proNRGα2c and the proNRGΔLinker mutant. Cells were labeled with 200 μCi/ml of a mixture of [35S]cysteine and [35S]methionine for 20 min, and then the medium was replaced by fresh, complete medium. Cells were lysed at the indicated times. The extracts were immunoprecipitated with the anti-proNRG antibody and analyzed in 8% SDS-PAGE gels, followed by autoradiography. The graphics below the gel shown the percent intensity of each band with respect to the sum of the signal corresponding to the 70–72-plus 80-kDa bands. (B) Effect of brefeldin A on proNRGα2c and proNRGΔLinker mutant. 293-NRGα2c and 293-NRGΔLinker cells were treated with or without brefeldin A (10 μg/ml) overnight and lysed. The extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation and Western blotting with the anti-proNRG antibody. (C) Endoglycosidase analysis of proNRGΔLinker mutant. 293-NRGΔLinker cells were treated with or without tunicamycin (10 μg/ml) overnight, lysed, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with the anti-proNRG antibody. Where indicated the immunocomplexes were digested with Endo H and analyzed by Western blot with the proNRG antibody. (D) Analysis of the role of N-linked glycosylation in the sorting of proNRGα2c and proNRGΔLinker. Cells were preincubated with or without tunicamycin (10 μg/ml, 12 h) and, where indicated, treated with proteinase K. The immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were as above.

We used brefeldin A to trap proNRGα2c and proNRGΔLinker in their early steps of biosynthesis. This treatment caused accumulation of a diffuse band close to the p80 form (Figure 4B). This pattern was indistinguishable between the proNRGα2c and proNRGΔLinker mutant, suggesting, together with the metabolic labeling data, that the deficient proNRGΔLinker sorting probably occurred beyond the early biosynthetic steps. Tunicamycin and Endo H experiments indicated that the faster migrating form of proNRGΔLinker was N-glycosylated and resided in an Endo H-sensitive compartment (Figure 4C). The p80 proNRGΔLinker form was resistant to Endo H, indicating that this form had moved away from the ER/cis-Golgi. Interestingly, tunicamycin treatment did not prevent cell surface exposure of the slower migrating form in both wild-type and proNRGΔLinker mutant (Figure 4D), indicating that N-linked glycosylation is dispensable for membrane sorting of proNRGα2c.

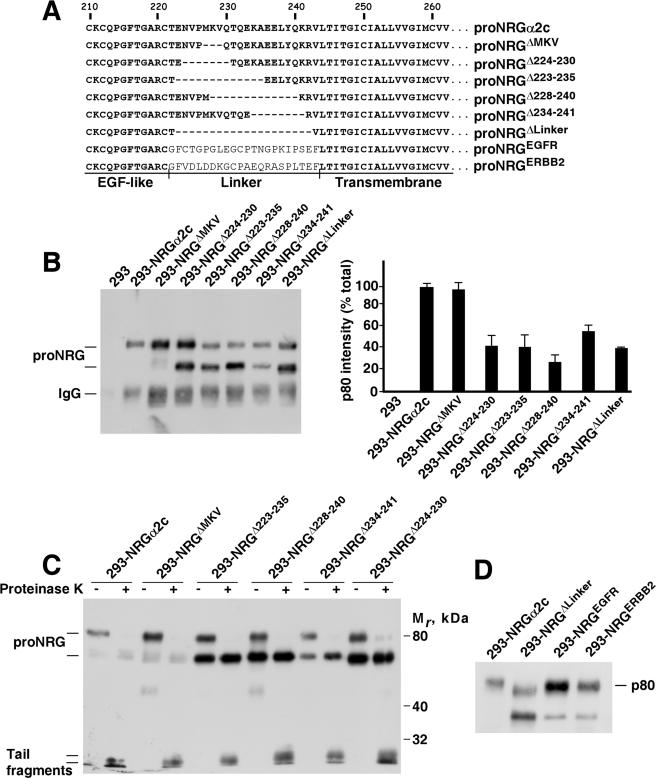

We next addressed whether the primary sequence present in the linker was critical for the surface targeting of proNRGα2c. To this end, we used several proNRGα2c mutants that included different deletions in the linker region (Figure 5A). Partial deletions of the linker caused an increase in the 70-kDa bands (Figure 5B), with independence of whether they were performed C-terminal to the NRG domain, or N-terminal to the transmembrane domain (Figure 5A). Protease protection experiments carried out on cells expressing these different mutants indicated that, in fact, the higher Mr form of proNRGα2c in the different mutants was mainly cell surface exposed (Figure 5C). The only mutant that behaved analogously to the wild-type form was the proNRGΔMKV form (Figure 5, B and C).

Figure 5.

Analysis of different mutants of the linker region of proNRGα2c. (A) Description of the sequences deleted or substituted in the different mutants of the linker region of proNRGα2c. (B) Expression of the different mutants of the linker region of proNRGα2c. Cells expressing the different mutants of the linker region were lysed, and samples were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by Western blot with anti-proNRG antibody. The histogram at the right is a quantitation of the percent intensity of the 80-kDa band, with respect to the total signal that comes from the sum of the p80, p72, and p70 bands. The results represent the mean ± SD of three different experiments. (C) Protease protection experiments of the different mutants of the linker region of proNRGα2c. (D) Expression of mutants in which the linker region of proNRGα2c has been substituted by juxtamembrane sequence of EGFR or ErbB2 in 293 cells. Cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoprecipitation and Western blot with anti-proNRG antibody.

We also substituted the proNRGα2c linker for two unrelated sequences of the juxtamembrane extracellular region of the EGFR or the ErbB2 receptor tyrosine kinase (Figure 5A). Transient transfection experiments (Figure 5D) as well as analyses of individual clones (data not shown) indicated analogous patterns of expression of the chimeric proteins and wild-type proNRGα2c. Furthermore, proteinase K protection experiments confirmed that these linker chimeric proteins reached the plasma membrane in a manner indistinguishable from the wild-type proNRGα2c (data not shown). Therefore, the proper sorting of proNRGα2c to the plasma membrane does not appear to depend on the strict primary sequence of the proNRGα2c linker.

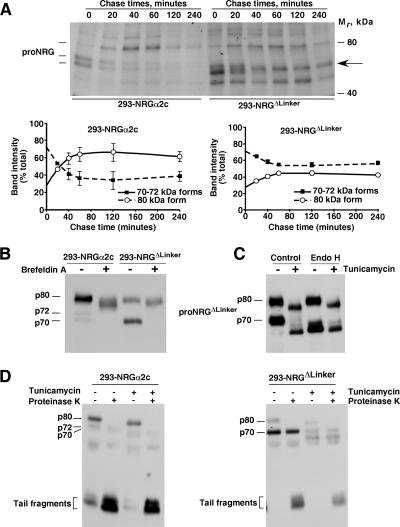

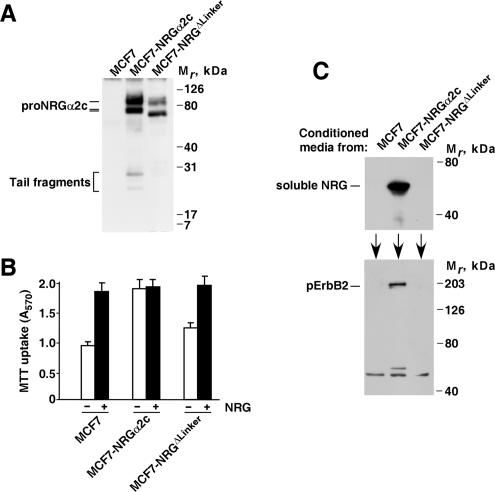

Biological Activity of Wild-Type pro-NRGα2c and the pro-NRGΔLinker Mutant

Intracellular forms of EGF have been shown to activate the EGFR intracellularly, a phenomenon termed intracrine stimulation (Wiley et al., 1998; Dong et al., 2005). To investigate whether intracellular proNRG behaved analogously, we used a cellular model based on MCF7 cells. These cells express low-to-normal levels of the ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 receptor tyrosine kinases and mitogenically respond to the addition of exogenous soluble NRG (Holmes et al., 1992; Agus et al., 2002). Transfection of the cDNAs coding for proNRGα2c and proNRGΔLinker in MCF7 cells resulted in the isolation of several clones that expressed these proNRG peptides (Figure 6A). The molecular forms of proNRGα2c and proNRGΔLinker present in these transfectants were analogous to those found in 293 cells, i.e., with the immature form predominating in the proNRGΔLinker mutant (Figure 6A). In addition, the truncated tail fragments were difficult to detect in MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells.

Figure 6.

Biological activity of the proNRGΔLinker mutant. (A) Expression of proNRGα2c and the proNRGΔLinker mutant in MCF7 cells. MCF7 cells expressing proNRGα2c (MCF7-NRGα2c) or proNRGΔLinker mutant (MCF7-NRGΔLinker) were lysed, immunoprecipitated, and blotted with the anti-proNRG antibody. (B) Proliferation of MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, and MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells. Cells were plated in 24-well plates and allowed to attach in complete medium for 12 h, before switching to serum-free medium with or without 10 nM NRG. MTT uptake was measured 5 d later. The results show the mean ± SD of quadruplicates of an experiment that was repeated four times. (C) Detection of soluble NRG in the conditioned media. Conditioned media from MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, and MCF7-NRGΔLinker was concentrated 10-fold and then analyzed by Western blot using the anti-NRG antibody (top panel). In the experiment shown in the lower panel, MCF7 cells were treated with conditioned media from MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, and MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells and then lysed. Samples were immunoprecipitated with an anti-ErbB2 antibody, and the blot was probed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies. The position of tyrosine phosphorylated ErbB2 is shown.

We investigated the growth properties of MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, and MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells. As shown in Figure 6B, MCF7-NRGα2c cells proliferated to higher densities than parental MCF7 cells. Addition of soluble NRG stimulated parental MCF7 proliferation to levels analogous to those obtained by MCF7-NRGα2c. As expected, the latter were insensitive to the addition of exogenous NRG. MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells proliferated slightly more than parental MCF7 cells, but much less than MCF7-NRGα2c. This was not due to a defect of the MCF7-NRGΔLinker because analogous results were obtained with other MCF7-NRGΔLinker clones (data not shown), and addition of soluble NRG caused this clone to increase MTT uptake to amounts analogous to those of MCF7-NRGα2c cells or MCF7 cells treated with NRG (Figure 6B).

The low presence of truncated fragments in blots from cells expressing the proNRGΔLinker provoked the question of whether the different biological properties of MCF7-NRGα2c and MCF7-NRGΔLinker were due to restricted shedding of the proNRGΔLinker mutant. To test this, conditioned media from MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, and MCF7-NRGΔLinker were collected and added to serum-starved MCF7 cells, and ErbB2 tyrosine phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting. Conditioned media from MCF7-NRGα2c cells contained soluble NRG, in contrast to media from MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells (Figure 6C, top panel). This result indicated that production of soluble NRG was profoundly compromised in cells expressing the proNRGΔLinker mutant. Incubation of MCF7 cells with conditioned media from MCF7-NRGα2c caused tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB2 (Figure 6C, bottom panel). However, incubation with the conditioned media from MCF7-NRGΔLinker or parental MCF7 cells did not induce any significant tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB2, confirming the poor release of NRG from proNRGΔLinker. Analogous data were obtained with conditioned media from 293 cells expressing wild-type proNRGα2c or proNRGΔLinker (data not shown).

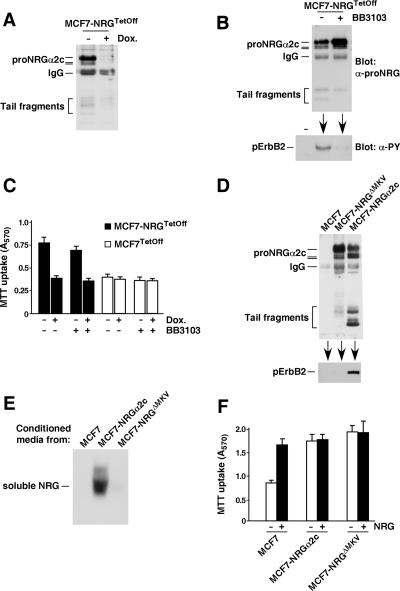

Biological Activity of Cell Surface Transmembrane pro-NRG Forms

To further evaluate the importance that shedding of proNRG may have on its action, we used two strategies: 1) we used BB3103, an hydroxamic acid derivative that prevents proNRGα2c shedding (Montero et al., 2000); and 2) we studied the biological activity of a proNRGα2c mutant (proNRGΔMKV) that is highly resistant to shedding (Montero et al., 2000). For the pharmacological studies and to avoid clonal differences, we used an MCF7 cell line in which proNRGα2c was expressed in a regulated manner using the tetracycline transactivator system (Figure 7A). In these cells, treatment with BB3103 caused accumulation of the full-length proNRGα2c form (Figure 7B, top panel) and prevented ErbB2 tyrosine phosphorylation caused by the conditioned media from these cells (Figure 7B, bottom panel). Repression of proNRGα2c caused a strong decrease in the proliferation of MCF7-NRGTetOff cells (Figure 7C), and treatment with BB3103 did not have any detectable effect on the ability of transfected transmembrane proNRGα2c to increase MTT uptake. Western blotting of proNRGα2c indicated that the drug was active throughout the length of the experiment (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Uncleavable proNRGα2c is active. (A) Regulated expression of proNRG in MCF7-NRGTetOff cells. MCF7-NRGTetOff cells cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (10 ng/ml) were analyzed for their expression by Western blotting with the proNRG antibody. (B) The metalloprotease inhibitor BB3103 prevents cleavage of proNRGα2c. MCF7-NRGTetOff cells were treated with or without BB3103 (20 μM) overnight, and expression of proNRGα2c was analyzed by immunoprecipitation and Western blot as above. On the other hand the conditioned medium of this experiment was used to analyze the phosphorylation of ErbB2 by Western blotting in MCF7 cells. (C) MCF7-NRGTetoff or MCF7Tetoff cells plated in 24-well plates in the presence or absence of doxycycline (10 ng/ml) were treated with or without BB3103 (20 μM), and MTT uptake was measured 5 d later. The data represent the mean ± SD of quadruplicates of an experiment that was repeated twice. (D) Expression of proNRGΔMKV in MCF7 cells. The conditioned media from these cells were used to stimulate MCF7 cells. The extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-ErbB2 antibody, and the blot was probed with the anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (bottom panel). (E) Production of soluble NRG by MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, and MCF7-NRGΔMKV cells. The media were concentrated 10-fold, and an aliquot was used for the Western analysis of soluble NRG production using the anti-NRG antibody. (F) Proliferation of MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, and MCF7-NRGΔMKV cells. The experimental conditions were as those described for the experiment shown in Figure 6B.

We also used MCF7 cells expressing proNRGΔMKV, a mutant that is correctly targeted to the plasma membrane (see Figure 5, B and C). MCF7-NRGΔMKV cells contained very small amounts of cell-bound truncated fragments (Figure 7D, top panel). The latter reflected poor release of NRG, as also demonstrated by Western blotting of conditioned media (Figure 7E). This restricted cleavage was also indicated by the failure of conditioned media from MCF7-NRGΔMKV cells to stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB2 (Figure 7D, bottom panel). Analysis of the growth properties of MCF7-NRGΔMKV cells indicated that their growth was analogous to that of MCF7-NRGα2c cells and could not be further increased upon exogenous NRG treatment (Figure 7F). These results suggested that even though shedding of the MKV mutant was profoundly compromised, the transmembrane factor may retain biological activity.

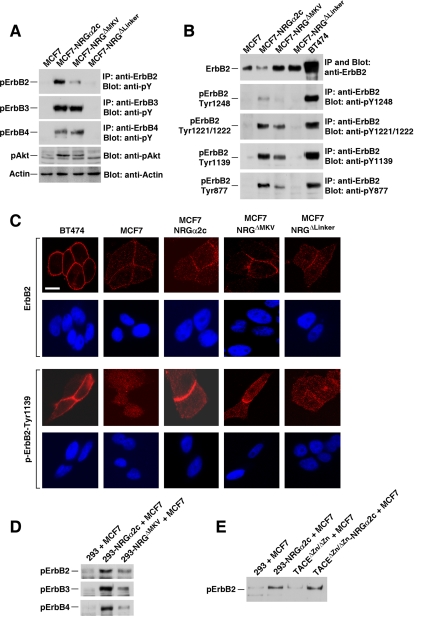

Transmembrane proNRG Forms Cause Constitutive Activation of ErbB-dependent Signaling Pathways

Immunoprecipitation with anti-ErbB2 antibodies, followed by Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine, indicated that ErbB2 was phosphorylated in cells that expressed proNRGα2c or proNRGΔMKV, but not in cells expressing the proNRGΔLinker mutant (Figure 8A). Analogous results were obtained when analyzing the tyrosine phosphorylation status of ErbB3 and ErbB4. Western analyses of signaling molecules that have been implicated in ErbB mitogenic signaling indicated constitutive phosphorylation of Akt in cells expressing proNRGα2c or proNRGΔMKV (Figure 8A). Therefore, it is likely that intracellular forms of proNRG may be unable to activate ErbB receptors, in contrast to cell surface–exposed forms.

Figure 8.

Transmembrane proNRG activates ErbB receptors in trans. (A) Activation of ErbB receptors and the Akt route by proNRGα2c and other mutants. MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, MCF7-NRGΔMKV, and MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-ErbB2, anti-ErbB3, or anti-ErbB4 antibodies. Western blot was performed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies. One part of the cellular extract was analyzed by Western blot with the anti-pAkt antibody. As a loading control a blot with anti-actin was performed. (B) Phosphorylation of ErbB2 at different tyrosine residues. MCF7, MCF7-NRGα2c, MCF7-NRGΔMKV, and MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-ErbB2 antibodies. Blots were probed with antibodies specific for ErbB2, pTyr1248, pTyr1221/1222, pTyr1139, and pTyr877 of ErbB2. The BT474 cell line was used as a control. (C) Analysis of the subcellular distribution of pY1139-ErbB2 by immunofluorescence microscopy. The different cell lines were plated on coverslips and analyzed with anti-ErbB2 or anti-pErbB2-Tyr1139 antibodies. (D) 293, 293-NRGα2c, or 293-NRGΔMKV cells were coincubated with MCF7 cells for 30 min, and the phosphorylation of ErbB2 analyzed by Western blotting as described above. (E) Coincubation experiment analogous to that presented in D, by using TACEΔZn/ΔZn or TACEΔZn/ΔZn-NRGα2c cells with MCF7 cells.

We analyzed the subcellular distribution of tyrosine-phosphorylated ErbB2 by immunofluorescence microscopy. To this end, we used a panel of antibodies directed to different phosphospecific sites within ErbB2. These antibodies were first tested in Western using as a control BT474 cells, in which ErbB2 is constitutively phosphorylated due to overexpression (e.g., see Lane et al., 2000; Agus et al., 2002; Yuste et al., 2005). As shown in Figure 8B, all the phosphorylation site–specific antibodies reacted with ErbB2 from BT474 cells. The antibody identifying pY1248 reacted poorly with ErbB2 receptors from MCF7-NRGα2c and MCF7-NRGΔMKV. Much better signals were obtained by using the antibodies that recognized pY1221/1222, pY1139, or pY877. In terms of signal intensity, the immunofluorescence analyses using these antibodies correlated with the Western blotting results, i.e., the anti-pY1248 gave a poor signal, and the best stainings were obtained with the anti-pY1139 and the anti-pY877 antibodies (data not shown). In BT474 cells, the anti-pY1139 uniformly stained the cell surface (Figure 8C), independently of whether cell–cell contacts were established or not. This is indicative of activation of ErbB2 by increased oligomerization frequency due to overexpression, a mechanism of activation that is ligand-independent (Ullrich and Schlessinger, 1990). In MCF7-NRGα2c and MCF7-NRGΔMKV cells, most of the anti-pErbB2 signal accumulated at cell–cell contact sites (Figure 8C). Very little immunofluorescent signal was present in cultures of MCF7 or MCF7-NRGΔLinker cells using these anti-pErbB2 antibodies.

The staining pattern at cell–cell contact sites in MCF7-NRGα2c and MCF7-NRGΔMKV cells suggested that transmembrane NRG could activate ErbB receptors in trans. To explore this possibility, we cocultured 293 cells expressing proNRGα2c or proNRGΔMKV, with MCF7 cells. Because 293 cells do not respond to NRG, any change in tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB receptors must correspond to the receptors expressed by MCF7 cells. Coincubation of MCF7 cells with 293-proNRGα2c, or 293-proNRGΔMKV cells caused stimulation of ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 receptors expressed by MCF7 cells (Figure 8D). It should be mentioned that the ability of the 293-proNRGΔMKV cells to stimulate the tyrosine phosphorylation of these receptors was below that induced by the 293-proNRGα2c cells. We also performed analogous coculture experiments using TACEΔZn/ΔZn cells expressing proNRGα2c (TACEΔZn/ΔZn-NRGα2c). TACEΔZn/ΔZn cells were isolated from mice on which the Zinc-binding region of the protease TACE was deleted by homologous recombination (Peschon et al., 1998). As a consequence, the protease is inactive and fails to cleave multiple membrane-bound proteins (Peschon et al., 1998), including proNRGα2c (Montero et al., 2000). Coincubation of MCF7 cells with TACEΔZn/ΔZn-NRGα2c provoked tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB2 (Figure 8E). However, when MCF7 cells were coincubated with TACEΔZn/ΔZn cells, that we used as a control, no significant increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB2 was detected.

DISCUSSION

The extracellular linker of membrane-anchored growth factors is the region where surface proteases act to release soluble forms of these factors. Based on this, the linker has been considered a critical region for the regulation of the balance between the soluble and transmembrane forms of membrane-anchored polypeptide factors. Here we show that this region is also required for adequate sorting of proNRGα2c to the plasma membrane. Furthermore, we show that a discrete mutation of the linker that does no affect cell surface sorting, but that impairs cleavage, is active, demonstrating that transmembrane proNRGs retain at least part of their biological properties. Thus, our data suggest that the linker may represent more than a mere region where cleavage occurs and indicate that this zone plays multiple functions in the biology of membrane-anchored growth factors.

Multiple molecular forms of proNRGα2c (p80, p72, and p70), together with some C-terminal cell bound fragments were identified. In pulse-chase experiments, the p70 and p72 forms appeared shortly after the start of the metabolic labeling and chased into the p80 form, suggesting that p70 and p72 are precursors of p80. Why two precursor forms are present instead of only one is yet unclear, but may indicate differential states of glycosylation of p70 and p72 in the initial steps of proNRGα2c biosynthesis. p70 and p72 may later gain additional posttranslational modifications, probably complex sugars, during their movement through intracellular compartments. The diffuse nature of the p80 band in Western blots may thus be a reflection of the sum of several heterogeneously glycosylated forms, p70 and p72 being the predominant precursors.

The subcellular location of the p80 form was distinct from that of the p70/p72 forms. p80 was present at the plasma membrane, whereas p70/p72 located intracellularly. Although p80 and p72 were sensitive to tunicamycin, only the latter was affected by Endo H. These data indicate that both p80 and p72 contain N-linked sugars and differentiate both proNRGα2c forms in their location, because Endo H attacks sugar chains at the cis-Golgi and previous compartments of the secretory pathway. Therefore, p72 must be a precursor form that has not yet escaped from the ER or, most likely, the cis-Golgi. Less obvious is the nature of p70. The latter form was apparently insensitive to tunicamycin or Endo H, indicating that p70 does not contain N-linked sugars or is not glycosylated at all. However, because this form was resistant to proteinase K, was not biotinylated, and could not be precipitated in cell surface immunoprecipitation experiments, we conclude that this form is not exposed at the cell surface and locates in a compartment of the secretory pathway.

The candidate compartment where p70 and p72 may reside is the Golgi, because most intracellular staining using the anti-proNRG antibody was coincident with the cis-Golgi marker GM130. The fact that p70/p72 were located at this compartment indicates that exit from the Golgi may represent a rate-limiting step in the sorting of proNRGα2c. This is further supported by the enhanced entrapment of proNRGΔLinker at this compartment. Although checkpoint controls have been well defined at the ER (Kleizen and Braakman, 2004), the presence of such controls at the Golgi apparatus has been less studied (Ellgaard and Helenius, 2003). However, evidence exists indicating that luminal (Yeaman et al., 1997; Gut et al., 1998), cytosolic (Wahlberg et al., 1995; Stockklausner and Klocker, 2003; Hofherr et al., 2005), or transmembrane (Kundu et al., 1996) determinants may control sorting from the Golgi. In the case of proNRGα2c, the linker sequence deleted does not contain any N-linked glycosylation consensus site and only includes a threonine that could act as an O-glycosylation site. However, this site has not been reported to be glycosylated (Burgess et al., 1995). Furthermore, the conservation of this threonine in mutants of the linker in which defective sorting occurs argues against the potential role of this residue in glycosylation-dependent sorting. Moreover, treatment with tunicamycin to prevent N-linked glycosylation in vivo did not affect surface exposure of proNRGα2c. In addition, the pulse-chase metabolic labeling and the brefeldin A experiments showed that in the initial steps of their biosynthesis proNRGα2c and proNRGΔLinker behaved analogously, indicating that the defect in the sorting of the latter must occur at a step beyond the biosynthesis and the cotranslational N-linked addition of sugars in the ER.

An open question is how deletions in the linker affect sorting. A possible scenario could be that of a Golgi checkpoint system that detects altered proNRG and prevents its sorting probably by interaction with resident Golgi proteins. It is worth mentioning that the proNRGΔIg mutant efficiently sorted to the plasma membrane. This indicates that the mere deletion of a random extracellular sequence cannot provoke intracellular retention and opens the possibility that a specific sequence in the linker could be required for efficient sorting. However, more subtle deletions both at the N-terminus or the C-terminus of the linker caused a phenotype analogous to deletion of the whole linker. In addition, substitution of the proNRGα2c linker by unrelated sequences, but preserving the length of the linker, created chimeric proteins that were efficiently transported to the surface. These data suggest that the linker may act as a spacer between the transmembrane domain and the rest of the extracellular domain and suggest that maintenance of a spacing between these regions may be required for efficient delivery of proNRGα2c to the plasma membrane. In addition to this domain, it is possible that other regions of proNRGs may be involved in membrane anchoring and plasma membrane sorting. In the case of the related membrane factor proTGFα, deletions of the intracellular cytosolic tail prevented its sorting to the plasma membrane (Briley et al., 1997; Fernandez-Larrea et al., 1999). As a result, proTGFα was deficiently cleaved and release of soluble factor was prevented (Bosenberg et al., 1992; Briley et al., 1997).

Another conclusion that can be obtained from our studies is the clear dissection between efficient sorting of proNRGα2c and its membrane association. In this respect, membrane association of proNRGΔLinker was undistinguishable from that of the wild type, as indicated by cell fractionation. Therefore, the linker is not critical for proNRGα2c membrane association.

In addition to the defect in sorting, deletions in the linker altered the biological properties of membrane-bound proNRGα2c. Deletions that resulted in intracellular entrapment of proNRG created a transmembrane form that was inactive. This was interesting because intracellular EGF stimulates the EGF receptor inside the cell (Wiley et al., 1998; Dong et al., 2005). In our experimental system, the proNRGΔLinker form was unable to cause stimulation of ErbB receptors. To explain this, several possible situations were contemplated, including defective cleavage or intracellular entrapment. Our data suggest that membrane-anchored proNRGα2c retains biological activity. Thus, expression in MCF7 cells of the proNRGΔMKV mutant, in which cleavage is profoundly impaired, resulted in proliferation rates at least as good as those obtained by MCF7-NRGα2c cells. Analogous results were reported for HB-EGF, a related EGF family transmembrane factor, on which deletion of five amino acids of the linker also prevented cleavage without affecting its juxtacrine action (Singh et al., 2004). Biochemically, membrane-bound proNRG provoked tyrosine phosphorylation of the ErbB receptors, and this appeared to be due to activation in trans, although our data cannot exclude that activation of ErbB receptors may also occur in cis. In fact, coincubation of 293-proNRGΔMKV cells with MCF7 cells caused tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4. In addition, analogous results were obtained in cocultures of MCF7 cells with TACEΔZn/ΔZn-NRGα2c cells. Finally, immunofluorescence analyses of MCF7 cells expressing proNRGα2c or proNRGΔMKV using anti-p-ErbB2 antibodies indicated that tyrosine-phosphorylated forms of ErbB2 accumulated at the sites of cell–cell contact. Clearly, the interaction in trans opens the interesting structural question of how ErbB receptors from a cell may interact with membrane-bound factors presented by another neighboring cell. The structures of soluble NRG with the ectodomain of ErbB receptors have been solved (reviewed in Burgess et al., 2003), but they do not clearly address how a transmembrane ligand may be able to activate the receptors present in neighboring cells. What can be postulated is that for this interaction to occur it is likely that a substantial degree of flexibility of both the ligand and the receptor must be required. Because cleavage appeared to be dispensable for proNRG activity, the failure of the proNRGΔLinker mutant to stimulate ErbB receptors or cell proliferation may be caused by its intracellular entrapment. Obviously, an additional possibility could be that of inability to activate ErbB receptors by steric reasons in the case of proNRGΔLinker.

Given the different experimental data obtained using distinct membrane-anchored growth factors and model systems, it appears risky to generalize with respect to the ability of these factors to be biologically functional in their transmembrane conformation. Rather, a more precise view may be one that considers different possible variables, such as the type of the membrane-bound factor and the cellular context, that in concert may explain the capabilities of the factors to act in a juxtacrine mode or not. Other concepts that must be clearly dissociated are those that refer to the physiological importance of shedding versus the capability of a membrane factor to be biologically active. Obviously, animal studies in mice indicate that shedding of membrane proteins is critical for animal development (Peschon et al., 1998; Hartmann et al., 2002; Sahin et al., 2004). This could be due to the fact that soluble forms of membrane factors may be required at sites distant from the cells that produce these factors. However, this property does not negate the concept that membrane-bound forms of growth factors may be biologically active, as far as the receptors for these factors are present in cells that are in physical contact with the cells that produce the factor. The development of additional in vitro and in vivo models to address these questions is an important challenge for studies in the area of membrane-anchored growth factor physiology and pathology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Spain (BMC2003-01192). R.R.-B. and L.Y. were supported by fellowships from the Ministry of Education and Culture, and A.E.O. was initially supported by the Scientific Foundation of the Spanish Association for Cancer Research (AECC), and later by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. J.B. was supported by a Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT/FSEIII), Quadro Comunitario de Apoio III. Our Cancer Research Institute and the work carried out at our laboratory received support from the European Community through the regional development funding program (FEDER).

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0511) on November 15, 2006.

REFERENCES

- Aguilar Z., Slamon D. J. The transmembrane heregulin precursor is functionally active. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:44099–44107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agus D., et al. Targeting ligand-activated ErbB2 signaling inhibits breast and prostate tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anklesaria P., Teixidó J., Laiho M., Pierce J. H., Greenberger J. S., Massagué J. Cell-cell adhesion mediated by binding of membrane-anchored transforming growth factor a to epidermal growth factor receptors promotes cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:3289–3293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J., Mendelsohn J., Kim Y. M., Pandiella A. Autocrine regulation of membrane transforming growth factor-a cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:3279–3284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobel C. P. ADAMs: key components in EGFR signalling and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:32–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell-Pages M., Rojo F., Albanell J., Baselga J., Arribas J. TACE is required for the activation of the EGFR by TGF-alpha in tumors. EMBO J. 2003;22:1114–1124. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosenberg M. W., Pandiella A., Massagué J. The cytoplasmic carboxy-terminal amino acid specifies cleavage of membrane TGF-α into soluble growth factor. Cell. 1992;71:1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann R., Lindquist P. B., Nagashima M., Kohr W., Lipari T., Napier N., Derynck R. Transmembrane TGF-α precursors activate EGF/TGF-α receptors. Cell. 1989;56:691–700. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briley G. P., Hissong M. A., Chiu M. L., Lee D. C. The carboxyl-terminal valine residues of proTGF alpha are required for its efficient maturation and intracellular routing. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:1619–1631. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britsch S., Li L., Kirchhoff S., Theuring F., Brinkmann V., Birchmeier C., Riethmacher D. The ErbB2 and ErbB3 receptors and their ligand, neuregulin-1, are essential for development of the sympathetic nervous system. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1825–1836. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A. W., Cho H. S., Eigenbrot C., Ferguson K. M., Garrett T. P., Leahy D. J., Lemmon M. A., Sliwkowski M. X., Ward C. W., Yokoyama S. An open-and-shut case? Recent insights into the activation of EGF/ErbB receptors. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess T. L., Ross S. L., Qian Y. X., Brankow D., Hu S. Biosynthetic processing of neu differentiation factor. Glycosylation trafficking, and regulated cleavage from the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:19188–19196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.19188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busfield S. J., et al. Characterization of a neuregulin-related gene, Don-1, that is highly expressed in restricted regions of the cerebellum and hippocampus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:4007–4014. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N., Díaz-Rodríguez E., Becker E., Zanca D. M., Pandiella A. TrkA receptor ectodomain cleavage generates a tyrosine-phosphorylated cell-associated fragment. J. Cell Biol. 1996;132:427–436. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraway K. L., 3rd, Weber J. L., Unger M. J., Ledesma J., Yu N., Gassmann M., Lai C. Neuregulin-2, a new ligand of ErbB3/ErbB4-receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1997;387:512–516. doi: 10.1038/387512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H., Riese D. J., 2nd, Gilbert W., Stern D. F., McMahan U. J. Ligands for ErbB-family receptors encoded by a neuregulin-like gene. Nature. 1997;387:509–512. doi: 10.1038/387509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi Y., Stern D. F. Membrane-anchored forms of EGF stimulate focus formation and intercellular communication. Oncogene. 1991;6:1151–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J., Opresko L. K., Chrisler W., Orr G., Quesenberry R. D., Lauffenburger D. A., Wiley H. S. The membrane-anchoring domain of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands dictates their ability to operate in juxtacrine mode. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:2984–2998. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J., Opresko L. K., Dempsey P. J., Lauffenburger D. A., Coffey R. J., Wiley H. S. Metalloprotease-mediated ligand release regulates autocrine signaling through the epidermal growth factor receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:6235–6240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L., Helenius A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:181–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparis-Ogando A., Diaz-Rodriguez E., Montero J. C., Yuste L., Crespo P., Pandiella A. Erk5 participates in neuregulin signal transduction and is constitutively active in breast cancer cells overexpressing ErbB2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:270–285. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.270-285.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparís-Ogando A., Díaz-Rodríguez E., Pandiella A. Signalling-competent truncated forms of ErbB2 in breast cancer cells: differential regulation by protein kinase C and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Biochem. J. 1999;344:339–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falls D. L. Neuregulins: functions, forms, and signaling strategies. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;284:14–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Larrea J., Merlos-Suarez A., Urena J. M., Baselga J., Arribas J. A role for a PDZ protein in the early secretory pathway for the targeting of proTGF-alpha to the cell surface. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:423–433. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach G. D., Rosen K. M. ARIA: a neuromuscular junction neuregulin. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1997;20:429–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembo M., Raz E., Shilo B. Z. The Drosophila embryonic midline is the site of Spitz processing, and induces activation of the EGF receptor in the ventral ectoderm. Development. 1996;122:3363–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gut A., Kappeler F., Hyka N., Balda M. S., Hauri H. P., Matter K. Carbohydrate-mediated Golgi to cell surface transport and apical targeting of membrane proteins. EMBO J. 1998;17:1919–1929. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari D., Tzahar E., Romano J., Shelly M., Pierce J. H., Andrews G. C., Yarden Y. Neuregulin-4, a novel growth factor that acts through the ErbB-4 receptor tyrosine kinase. Oncogene. 1999;18:2681–2689. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. C., Chung E., Coffey R. J. EGF receptor ligands. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;284:2–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D., et al. The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is essential for Notch signalling but not for alpha-secretase activity in fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:2615–2624. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama S., Iwamoto R., Goishi K., Raab G., Taniguchi N., Klagsbrun M., Mekada E. The membrane protein CD9/DRAP 27 potentiates the juxtacrine growth factor activity of the membrane-anchored heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:929–938. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle C. L., Sunnarborg S. W., Loiselle D., Parker C. E., Stevenson M., Russell W. E., Lee D. C. Selective roles for tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme/ADAM17 in the shedding of the epidermal growth factor receptor ligand family: the juxtamembrane stalk determines cleavage efficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:24179–24188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofherr A., Fakler B., Klocker N. Selective Golgi export of Kir2.1 controls the stoichiometry of functional Kir2.x channel heteromers. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1935–1943. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes W. E., et al. Identification of heregulin, a specific activator of p185erbB2. Science. 1992;256:1205–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juanes P. P., Ferreira L., Montero J. C., Arribas J., Pandiella A. N-terminal cleavage of proTGFalpha occurs at the cell surface by a TACE-independent activity. Biochem. J. 2005;389:161–172. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleizen B., Braakman I. Protein folding and quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu A., Avalos R. T., Sanderson C. M., Nayak D. P. Transmembrane domain of influenza virus neuraminidase, a type II protein, possesses an apical sorting signal in polarized MDCK cells. J. Virol. 1996;70:6508–6515. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6508-6515.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane H. A., Beuvink I., Motoyama A. B., Daly J. M., Neve R. M., Hynes N. E. ErbB2 potentiates breast tumor proliferation through modulation of p27(Kip1)-Cdk2 complex formation: receptor overexpression does not determine growth dependency. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:3210–3223. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3210-3223.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H. S., et al. Post-translational processing of membrane-associated neu differentiation factor proisoforms expressed in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4775–4783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. Epidermal growth factor-like transforming growth factor. II. Interaction with epidermal growth factor receptors in human placenta membranes and A431 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:13614–13620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J., Pandiella A. Membrane-anchored growth factors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1993;62:515–541. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D., Birchmeier C. Multiple essential functions of neuregulin in development. Nature. 1995;378:386–390. doi: 10.1038/378386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D., Yamaai T., Garratt A., Riethmacher-Sonnenberg E., Kane D., Theill L. E., Birchmeier C. Isoform-specific expression and function of neuregulin. Development. 1997;124:3575–3586. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero J. C., Yuste L., Díaz-Rodríguez E., Esparís-Ogando A., Pandiella A. Differential shedding of transmembrane neuregulin isoforms by the tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000;16:631–648. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peles E., Bacus S. S., Koski R. A., Lu H. S., Wen D., Ogden S. G., Levy R. B., Yarden Y. Isolation of the Neu/HER-2 stimulatory ligand: a 44 kd glycoprotein that induces differentiation of mammary tumor cells. Cell. 1992;69:205–216. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90131-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon J. J., et al. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 1998;282:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenzel N., Zwick E., Daub H., Leserer M., Abraham R., Wallasch C., Ullrich A. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. 1999;402:884–888. doi: 10.1038/47260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U., Weskamp G., Kelly K., Zhou H. M., Higashiyama S., Peschon J., Hartmann D., Saftig P., Blobel C. P. Distinct roles for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in ectodomain shedding of six EGFR ligands. J. Cell Biol. 2004;164:769–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. B., Tsukada T., Zent R., Harris R. C. Membrane-associated HB-EGF modulates HGF-induced cellular responses in MDCK cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:1365–1379. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockklausner C., Klocker N. Surface expression of inward rectifier potassium channels is controlled by selective Golgi export. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17000–17005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunnarborg S. W., et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme (TACE) regulates epidermal growth factor receptor ligand availability. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:12838–12845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich A., Schlessinger J. Signal transduction by receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. Cell. 1990;61:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90801-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg J. M., Geffen I., Reymond F., Simmen T., Spiess M. trans-Golgi retention of a plasma membrane protein: mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of the asialoglycoprotein receptor subunit H1 result in trans-Golgi retention. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130:285–297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen D., et al. Structural and functional aspects of the multiplicity of Neu differentiation factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:1909–1919. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley H. S., Woolf M. F., Opresko L. K., Burke P. M., Will B., Morgan J. R., Lauffenburger D. A. Removal of the membrane-anchoring domain of epidermal growth factor leads to intracrine signaling and disruption of mammary epithelial cell organization. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1317–1328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S. T., Winchell L. F., McCune B. K., Earp H. S., Teixidó J., Massagué J., Herman B., Lee D. C. The TGF-α precursor expressed on the cell surface binds to the EGF receptor on adjacent cells, leading to signal transduction. Cell. 1989;56:495–506. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki S., et al. Mice with defects in HB-EGF ectodomain shedding show severe developmental abnormalities. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:469–475. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Jiang D., Li W., Liang J., Gentry L. E., Brattain M. G. Defective cleavage of membrane bound TGFalpha leads to enhanced activation of the EGF receptor in malignant cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:1901–1914. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeaman C., Le Gall A. H., Baldwin A. N., Monlauzeur L., Le Bivic A., Rodriguez-Boulan E. The O-glycosylated stalk domain is required for apical sorting of neurotrophin receptors in polarized MDCK cells. J. Cell Biol. 1997;139:929–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste L., Montero J. C., Esparis-Ogando A., Pandiella A. Activation of ErbB2 by overexpression or by transmembrane neuregulin results in differential signaling and sensitivity to herceptin. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6801–6810. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Sliwkowski M. X., Mark M., Frantz G., Akita R., Sun Y., Hillan K., Crowley C., Brush J., Godowski P. J. Neuregulin-3 (NRG3): a novel neural tissue-enriched protein that binds and activates ErbB4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:9562–9567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]