Abstract

Neutrophils and Dictyostelium use conserved signal transduction pathways to decipher chemoattractant gradients and migrate directionally. In both cell types, addition of chemoattractants stimulates the production of cAMP, which has been suggested to regulate chemotaxis. We set out to define the mechanism by which chemoattractants increase cAMP levels in human neutrophils. We show that chemoattractants elicit a rapid and transient activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC). This activation is sensitive to pertussis toxin treatment but independent of phosphoinositide-3 kinase activity and an intact cytoskeleton. Remarkably, and in sharp contrast to Gαs-mediated activation, chemoattractant-induced AC activation is lost in cell lysates. Of the nine, differentially regulated transmembrane AC isoforms in the human genome, we find that isoforms III, IV, VII, and IX are expressed in human neutrophils. We conclude that the signal transduction cascade used by chemoattractants to activate AC is conserved in Dictyostelium and human neutrophils and is markedly different from the canonical Gαs-meditated pathway.

INTRODUCTION

Many types of cells have the ability to migrate directionally when exposed to gradients of chemoattractants. This chemotactic response is essential for a variety of physiological processes and is initiated when chemoattractants bind surface receptors and activate a wide range of signal transduction cascades, which ultimately lead to cellular polarization and migration (Parent, 2004). The acquisition of polarity is accompanied by a dramatic redistribution of cytoskeletal components, where F-actin and numerous actin-binding proteins are enriched at the front or leading edge and myosin II is assembled on the sides and at the back or trailing edge (Van Haastert and Devreotes, 2004; Bagorda et al., 2006).

A striking chemotactic behavior is exhibited by neutrophils as they move across vascular barriers and navigate to sites of inflammation (Niggli, 2003b; Parent, 2004). The agents that induce directed migration of neutrophils include a large and diverse group of chemoattractants originating from different sources (Uhing and Snyderman, 1999). These agents include formylated peptides secreted by bacteria (such as N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine [fMLP]), products of the complement cascade (such as complement factor 5a [C5a]), and phospholipid metabolites (such as leukotriene B4 [LTB4]) as well as a large family of chemokines that are derived from endothelial, epithelial, and stromal cells (Baggiolini, 1998). Remarkably, neutrophils can also relay the signal to surrounding cells by stimulating the production and release of more attractants, such as LTB4 and interleukin (IL)-8, which act in a paracrine manner to spread the chemotactic response to surrounding cells (Bazzoni et al., 1991; Baggiolini et al., 1994; Kannan, 2002). Chemoattractants bind to serpentine transmembrane receptors that couple to heterotrimeric G proteins (Murphy, 1996). Receptor activation leads to the dissociation of the G protein into α- and βγ-subunits, which go on to stimulate a variety of effectors that ultimately lead to cellular polarization and migration.

Several studies have established that the addition of chemoattractants to neutrophils causes an increase in the production of cAMP (Simchowitz et al., 1980; Smolen et al., 1980; Spisani et al., 1996; Suzuki et al., 1996; Ali et al., 1998). Although a clear correlation between total cAMP levels and chemotaxis has not been established, many studies have shown that, in neutrophils, increases in cAMP levels inhibit chemotaxis (Harvath et al., 1991; Elferink and VanUffelen, 1996; VanUffelen et al., 1998; Ariga et al., 2004). Furthermore, cAMP has been shown to regulate chemotactic migration in other cell types. O'Conner et al. 1998, 2000 have determined that the chemotactic migration of invasive carcinoma cells depends on cAMP in a RhoA-dependent manner, and studies using embryonic Xenopus spinal neurons have clearly established that the directionality of growth cones induced by many guidance factors can be switched by competitive analogues of cAMP or inhibitors of protein kinase A (PKA) (Ming et al., 1997). Although the mechanism by which cAMP controls chemotaxis remains to be established, it has been demonstrated that a variety of cytoskeletal and signaling components, including Rho and VASP, are regulated by PKA—the main intracellular target of cAMP (Howe et al., 2002). It therefore seems that modulation of intracellular cAMP levels is commonly used to regulate cell migration.

In neutrophils, the mechanism by which chemoattractants increase cAMP levels, which is synthesized from ATP by adenylyl cyclases, remains to be determined. Mammalian genomes harbor nine distinct G protein-coupled adenylyl cyclases (ACI-ACIX), composed of two sets of six transmembrane domains each followed by a conserved catalytic domain within a cytoplasmic loop (referred to as C1 and C2) (Tang and Hurley, 1998; Sunahara and Taussig, 2002). The nine ACs show distinct expression profiles and modes of regulation by G proteins, calcium, posttranslational modifications, and a variety of small molecules. Whereas all isoforms are stimulated by Gαs, only ACV and ACVI are sensitive to inhibition by Gαi. In contrast, Gβγ-subunits can be either stimulatory, as for ACII, ACIV, and ACVII, or inhibitory, as for ACI and ACVIII. ACIX is the most divergent isoform of ACs and constitutes a separate subfamily of ACs (Tang and Hurley, 1998; Sunahara and Taussig, 2002). Like all transmembrane ACs, ACIX is stimulated by Gαs, but unlike ACI-ACVIII, ACIX is insensitive to forskolin stimulation, a diterpene from the plant Coleus forskohlii (Premont et al., 1996; Hacker et al., 1998). In mammalian cells, the canonical pathway leading to AC activation involves the activation of the heterotrimeric G proteins Gαsβγ. The cascade is initiated by the release of Gαs and Gβγ subunits from the heterotrimer, which then go on to activate ACs, either alone (for Gαs) or synergistically (Tang and Gilman, 1991; Lustig et al., 1993). It has been established that chemoattractants mediate most of their effects, including increases in cAMP levels, through the pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive G protein Gαiβγ (Suzuki et al., 1996; Niggli, 2003b). Interestingly, a non-Gαsβγ pathway also regulates the chemoattractant-mediated activation of the adenylyl cyclase ACA in the social amoebae Dictyostelium (Saran et al., 2002; Kriebel and Parent, 2004). Genetic and biochemical analyses have established that ACA requires Gβγ-subunits, the cytosolic regulator cytosolic regulator of adenylyl cyclase (CRAC), and the target of rapamycin complex 2 (TORC2) (Insall et al., 1994; Lilly and Devreotes, 1995; Chen et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1999; Comer et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2005). Because many chemoattractant-mediated signal transduction cascades are conserved between neutrophils and Dictyostelium, we hypothesize that the events leading to the activation of AC in neutrophils are analogous to the events leading to the activation of ACA in Dictyostelium. We therefore set out to investigate the signal transduction events controlling the chemoattractant-mediated increase in cAMP levels in human neutrophils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The following reagents were obtained commercially from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO): fMLP, LTB4, IL-8, C5a, isoproterenol (Iso), forskolin, 1,9 dideoxyforskolin, 3-isobutyl1-methylxanthine (IBMX), latrunculin B (LatB), diisopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP), nocodazole (Noco), blebbistatin, Clostridium difficile toxin B, Y-27632, and histopaque 1077. LY294002 was obtained from AG Scientific. Texas Red X-phalloidin was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). iScript and iQ SYBER Green Supermix were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Radiolabeled [32P]α-ATP was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA). Phospho-AKT (Ser473) and AKT antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). TRIzol and Superscript II were obtained from Invitrogen.

Isolation of Peripheral Blood Neutrophils

Heparinized whole blood was obtained by venipuncture from healthy donors. Neutrophils were isolated by dextran sedimentation coupled to differential centrifugation over Histopaque 1077, similar to the method described previously (Boyum, 1974). Three rounds of hypotonic lysis with 0.2 and 1.6% saline removed residual red blood cells. Purified neutrophils were resuspended in modified Hanks' balanced salt solution (mHBSS; 10 mg/ml glucose, 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM HEPES) and kept on ice until used. For the preparation of samples used for immunoblotting, neutrophils were treated with 2 mM diisofluorophosphate (DFP) for 20 min and resuspended in modified Hanks' balanced salt solution with protease inhibitors.

Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK)293T Cells

HEK293T cells were maintained in DMEM media + 10% serum on 100-mm plates. Cells were grown to 80% confluence for experimental samples. Cells were dislodged with Versene, washed twice with mHBSS, and placed on ice. Cells were warmed to room temperature (RT) before adenylyl cyclase assay.

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Analysis

Neutrophil RNA was purified using the TRIzol reagent according to manufacturer instructions. One microgram of total RNA was used in RT reactions with human AC isoform-specific primers (see Supplemental Table 1). We used 100 ng of human brain mRNA as a positive control. RT reactions using Superscript II were performed at 42°C for 2 h. Subsequent PCR analysis used 40 cycles to identify low abundance RNA message. Aliquots were run on Tris borate-EDTA gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR

PCR amplification using a Bio-Rad iCycler system was carried out in a 20-μl reaction mixture in 96-well PCR plate. The reaction components were 0.2 μl of cDNA, 1X iQ Syber Green Supermix, and 100 nM each primer (see Supplemental Table 1). The reactions were incubated at 95°C for 30 s followed by 50 cycles of amplification at 95°C (30 s) for melting and at 55°C (30 s) for annealing and extension. After cycling, melt curves of the resultant PCR products were acquired. Serial dilutions of cloned PCR products were included for controls. The results are represented as the ratio of 1/(AC isoform threshold cycle/GAPDH threshold cycle) to establish relative expression. The data represents the analysis of five independent experiments.

AKT Phosphorylation Assay

Neutrophils were treated with DMSO or 100 μM LY294002 for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then stimulated with 50 nM fMLP for 5 min. Aliquots were taken for Western analysis before and 5 min after fMLP addition. Total cell lysates were run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Detection of Phospho-AKT (Ser473) and total AKT proteins was performed using commercially available antibodies, and detection was achieved using chemiluminescence with a goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-coupled antibody.

Chemotaxis Assay

Neutrophils were resuspended at 1 × 107/ml in mHBSS. One hundred microliters of cells were placed in the upper chamber of a 5-μm pore size transwell chamber (3421; Corning Life Sciences, Acton, MA). Chemoattractant resuspended in mHBSS was placed in the lower compartment. The apparatus was incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h. Cells that had migrated through the well into the lower chamber were counted using an automated Coulter counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Adenylyl Cyclase Assay

Neutrophils were resuspended at 2 × 107/ml in mHBSS and stimulated with various compounds. Aliquots of cells were taken at specific time points and rapidly lysed through a 5-μm membrane. Samples were transferred to an AC assay mix containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 μM ATP, 100 μM cAMP, 100 μM dithiothreitol (DTT), 200 μM IBMX, and 0.5 μCi of [32P]α-ATP (final concentrations) and incubated for 5 min. IBMX and DTT are added to the reaction mix to inhibit phosphodiesterase activity. Furthermore, a high concentration of cold cAMP is present to ensure that any residual phosphodiesterase activity mainly acts on the cold cAMP and spare the [32P]cAMP generated from the [32P]ATP. The reactions were stopped with the addition of 0.1% SDS and 1 mM ATP. Radiolabeled cAMP produced in the reaction was purified by sequential chromatography over Dowex 50W x4 and Alumina columns (Salomon, 1979). AC measurements by this assay exhibit considerable variation from experiment to experiment. Although the relative extent of activation is highly reproducible, the absolute activity can vary significantly up to twofold from day to day. Therefore, we have chosen to present AC activation data as an average of -fold stimulation from at least three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate on any given day. The basal and peak AC stimulation after the addition of 10 μM fMLP ranged from 2.4 to 4.3 and 6.8 to 12.9 pmol/min/mg protein, respectively.

Microscopy

For microscopic observation of actin polymerization, neutrophils were allowed to adhere to gelatin-coated coverslips for 10 min. Neutrophils were stimulated with 10 nM fMLP and then fixed (1% formaldehyde, 0.125% glutaraldehyde, and 0.01% Triton X-100 in mHBSS) after 10 min. Cells were blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline and stained with Texas Red X-phalloidin (Invitrogen).

RESULTS

Chemoattractants Rapidly and Transiently Stimulate Transmembrane Adenylyl Cyclases in a Gαi-dependent Manner

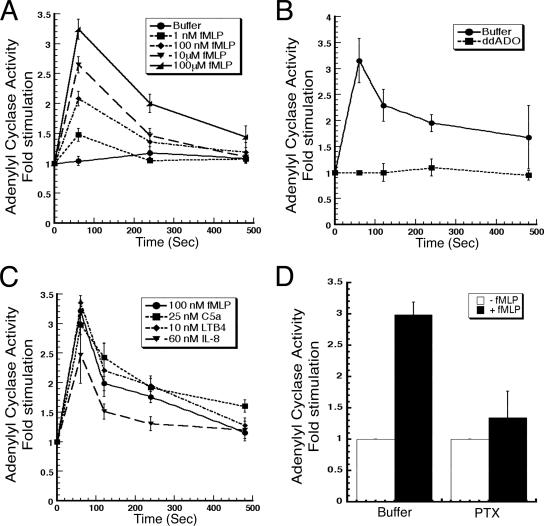

To determine the mechanism that regulates the chemoattractant-mediated accumulation of cAMP, we measured the effect of chemoattractants on AC activity using an activation trap assay. In this assay, cells are stimulated with various concentrations of chemoattractants, and, at specific times, cells are rapidly filter lysed into a [32P]ATP-containing mixture, and AC activity is assayed by measuring the [32P]cAMP produced (see Materials and Methods). As depicted in Figure 1A, addition of the formylated peptide fMLP to neutrophils induces a rapid, dose-dependent, and transient stimulation of AC activity, peaking at 1 min and returning to basal levels after 7–8 min. To determine whether this response is dependent on G protein-coupled transmembrane ACs, we pretreated cells with the potent P-site inhibitor dideoxyadenosine, which specifically acts on transmembrane ACs (Han et al., 2005). We found that it completely inhibits the response to 1 μM fMLP (Figure 1B). We next determined whether the ability of fMLP to stimulate AC activity is a common feature of chemoattractants. We find that a wide range of chemoattractants exhibit this property. Figure 1C shows the response induced by the end target chemoattractant C5a as well as endogenous agents such as LTB4 and IL-8. Together, these findings establish that the chemoattractant-mediated elevation in cAMP production observed in neutrophils is mediated by an increase in AC activity.

Figure 1.

Chemoattractants rapidly and transiently stimulate transmembrane AC activity. (A) Neutrophils were stimulated with various concentrations of fMLP. Aliquots were taken at 0, 1, 4, and 8 min and filter lysed into a reaction mix containing [32P]ATP to measure de novo synthesis of [32P]cAMP (see Materials and Methods). (B) Cells were pretreated with the P-site inhibitor dideoxyadenosine at 300 nM for 10 min at RT, and AC activity in response to 1 μM fMLP was measured as described in A. (C) Assays were performed as described in A in response to fMLP, C5a, LTB4, or IL-8. Results are presented as -fold stimulation of AC activity. (D) Neutrophils were incubated with 450 μg/ml PTX or with buffer for 2 h at 37°C and AC activity was measured just before (−fMLP) and 1 min after the addition of 10 μM fMLP (+fMLP). For all experiments, data are presented as the average -fold stimulation over basal for at least three independent experiments done in duplicate for each time point (see Materials and Methods).

Many of the chemoattractant-mediated responses are transduced through Gi heterotrimeric G proteins, which are specifically inactivated by the PTX-mediated ADP-ribosylation of Gαi (Niggli, 2003b). To determine whether coupling to Gαi also mediates AC activation, we assessed the effects of PTX on fMLP-mediated AC activation. The incubation of neutrophils with PTX for 2 h effectively inhibited Gαi function, because this treatment almost completely inhibited neutrophil chemotaxis to fMLP (data not shown). Not surprisingly, we also measured a significant inhibition of fMLP-mediated AC activation in PTX-treated neutrophils (Figure 1D). Similar results were obtained with C5a-, LTB4-, and IL-8–mediated stimulation (data not shown). These results show that the chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC is mediated through Gαiβγ.

The Chemoattractant-mediated Adenylyl Cyclase Activation in Neutrophils Is Insensitive to Forskolin

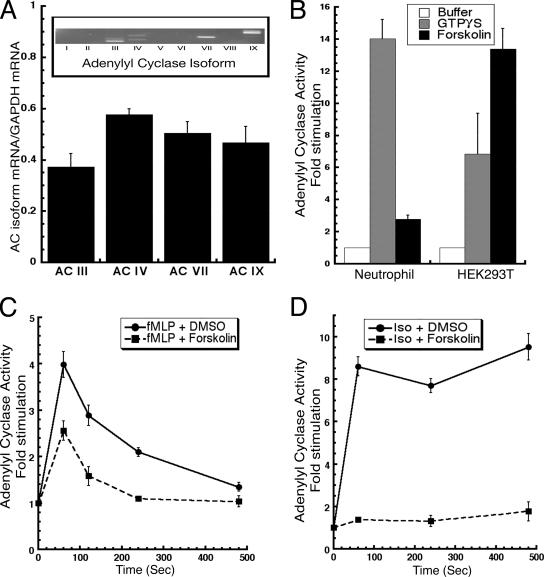

RT-PCR analysis performed on RNA extracts showed that, of the nine mammalian AC enzymes, isoforms III, IV, VII, and IX are expressed in human neutrophils (Figure 2A, inset). Further analysis using real-time PCR established that ACIII is the least abundant isoform and that isoforms IV, VII, and IX are expressed at similar levels (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

ACIX may be the predominant isoform present in neutrophils. (A) Purified RNA from whole blood neutrophils was subjected to RT-PCR by using AC isoform-specific primers (see Supplemental Table 1). The agarose gel electrophoresis is presented as an inset in A. First-strand cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR analysis for the presence of ACIII, IV, VII, and IX mRNAs as a function of GAPDH mRNA present in each sample. Relative expression is represented as the threshold cycle of each isoform/the threshold cycle for GAPDH for each sample. (B) HEK293T or neutrophils were filter lysed and buffer-, 100 μM GTPγS-, or 100 μM forskolin-mediated AC activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Neutrophils were stimulated with 1 μM fMLP and, at specific times, filter lysed into a reaction mix containing DMSO (control) or 100 μM forskolin. AC activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Neutrophils were stimulated with 100 μM isoproterenol, and at specific times, filter lysed into a reaction mix containing DMSO (control) or 100 μM forskolin. AC activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. For all experiments, data are presented as the average -fold stimulation over basal for at least three independent experiments done in duplicate for each time point (see Materials and Methods).

To gain more insight into the AC expression profile in neutrophils, we measured the effect of guanosine 5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate (GTPγS) and forskolin on AC activity in neutrophil lysates. GTPγS is a nonhydrolysable form of GTP that directly activates all heterotrimeric G proteins, releasing Gα subunits from Gαβγ trimers as well as small GTPases. As expected, we found that the addition of GTPγS leads to a robust stimulation of AC activity (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, and in contrast to the response observed in HEK293T cells, we observed the activity to be largely forskolin-insensitive (Figure 2B). Because ACIX is the only G protein-coupled AC insensitive to forskolin stimulation, this finding suggests that ACIX is the predominant isoform present, at the protein level, in neutrophils. To further investigate this behavior we measured the effect of forskolin on fMLP-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity. In these experiments, cells are stimulated with fMLP, filter lysed into the [32P]ATP reaction mix containing forskolin, and assayed. We found that the presence of the diterpene did not significantly alter the ability of fMLP to stimulate AC activity, confirming our results with forskolin alone (Figure 2C): the decreased -fold stimulation observed in the presence of forskolin is due to the small increase in basal AC activity observed in the presence of forskolin alone (Figure 2B). In contrast, when we assessed the effect of forskolin on Gαs-mediated activity, we found that forskolin dramatically inhibited the isoproterenol-mediated activation (Figure 2D). To show that our findings with forskolin were dependent on its ability to activate adenylyl cyclase, we tested the nonadenylyl cyclase-activating analogue 1,9 dideoxyforskolin and found that it did not alter isoproterenol-mediated adenylyl cyclase activity in neutrophils (data not shown). Together, these results show that chemoattractants and β-adrenergic agonists use signals to activate AC that are differentially regulated by forskolin.

Chemoattractant-mediated Activation of Adenylyl Cyclases Adapts to a Constant Level of Stimulus

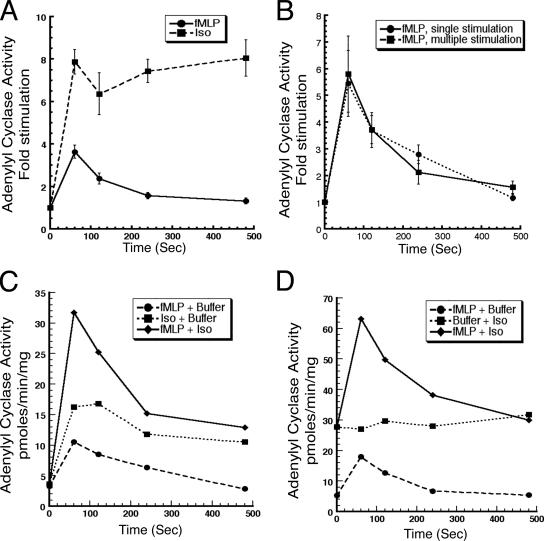

In sharp contrast to the sustained activation profile observed after stimulation with isoproterenol, the chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC is transient, showing an excitation peak followed by a return of the response to basal levels (Figure 3A). This activation profile is reminiscent of the AC response observed following chemoattractant addition to Dictyostelium cells (Dinauer et al., 1980). To determine whether the transient chemoattractant-mediated AC activation in neutrophils is due to the loss of active fMLP during the 8-min assay period, we stimulated cells with a saturating dose of fMLP every 2 min during the assay period and measured enzyme activity. Under these conditions, we again found that the activation profile retains its transient nature, indicating that the AC turns off in the presence of persistent fMLP signal (Figure 3B). These findings show that the chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC is similar to what we observe in Dictyostelium, displaying a rapid peak of activation that occurs ∼1 min after stimulation, followed by a turn off phase where the activity goes back down to basal levels after 8 min.

Figure 3.

Chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC adapts to constant levels of stimulus. (A) Neutrophils were stimulated with either 10 μM fMLP or 100 μM isoproterenol, and AC activity was assayed as described in the legend of Figure 1. (B) Neutrophils were stimulated with a single dose (10 μM) or multiple doses (10 μM) of fMLP at 2-min intervals. AC activity was measured as described in the legend of Figure 1. (C) Neutrophils were stimulated with 10 μM fMLP or 100 μM isoproterenol, or costimulated with fMLP and isoproterenol and AC activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Neutrophils were stimulated with 10 μM fMLP and after lysis, transferred to a reaction mix supplemented with buffer or 100 μM isoproterenol. As a control, cells were stimulated with buffer, lysed, and transferred to a reaction mix containing 100 μM isoproterenol. For results presented in C and D, representative data of at least three independent experiments done in duplicate for each time point are shown (see Materials and Methods).

To gain more insight into the mechanism of the turn off response, we next asked whether the inhibition pathway could be overcome by a Gαs-mediated signal. We costimulated whole cells with fMLP and isoproterenol and measured AC activity at specific times. We found that costimulation resulted in an additive or slightly synergistic activation peak followed by a return to levels of activity elicited by isoproterenol alone (Figure 3C). We obtained a similar result when we added isoproterenol to lysates. In these experiments, cells treated with or without fMLP, were filter lysed into the [32P]ATP reaction mix containing isoproterenol, and AC activity was assayed. As depicted in Figure 3D, in the absence of fMLP, the isoproterenol present in the reaction mix gives rise to a constant high level of AC activity. With fMLP stimulation, the isoproterenol-mediated activity quickly rises and comes back to pre-fMLP levels after 8 min. Together, these results show that the chemoattractant-mediated turn off pathway on AC does not impact on the activation signal elicited by Gαs and suggest that chemoattractants and β-adrenergic agonists activate AC via two independent cascades.

The Cytoskeleton Does Not Regulate Chemoattractant-mediated Activation of Adenylyl Cyclases

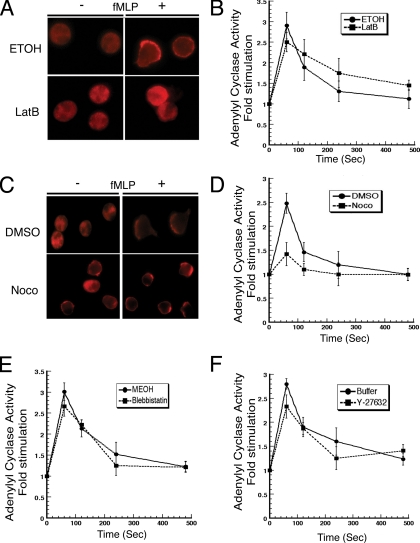

On chemoattractant stimulation, neutrophils rapidly assemble a dense network of cortical F-actin that becomes polarized to the leading edge of chemotaxing cells (Niggli, 2003b; Parent, 2004). Because F-actin has been reported to amplify chemoattractant signals via a positive feedback loop to the effector PI3K, we set out to determine whether the actin cytoskeleton could also regulate the chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC (Niggli, 2000; Weiner et al., 2002). For these experiments, we pretreated neutrophils with 40 μg/ml latrunculin B for 30 min, which completely inhibited the fMLP-mediated burst in F-actin polymerization as well as chemotaxis to fMLP (Figure 4A; data not shown). In sharp contrast, we found that latrunculin B treatment had no effect on fMLP-mediated AC activity (Figure 4B). In agreement with these findings, we also found that RhoGTPases are not required, as neutrophils treated with C. difficile toxin B show normal fMLP-mediated AC activation (data not shown).

Figure 4.

The cytoskeleton does not regulate chemoattractant-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase. (A) Neutrophils were treated with or without 40 μg/ml latrunculin B for 30 min to disrupt actin filaments and allowed to adhere to a gelatin-coated coverslip for 10 min. Cells were stimulated with 10 nM fMLP for 10 min followed by fixation and staining with Texas Red X-phalloidin to visualize F-actin localization. (B) Control and latrunculin B-treated cells were stimulated with 10 μM fMLP, and AC activity was assessed as described in legend of Figure 1. (C) Neutrophils were treated with or 30 μM nocodazole for 30 min to disrupt microtubules. Actin assembly was assessed for control and nocodazole-treated cells as described in A. (D) Control and nocodazole-treated cells were stimulated with 10 μM fMLP, and AC activity was assessed as described in legend of Figure 1. (E and F) Neutrophils were treated with 100 μM blebbistatin (E) or 10 μM Y-27632 (F) for 30 min and processed for fMLP-mediated AC activity as described in legend of Figure 1.

We next assessed the potential role of microtubules on AC activation. It has been suggested that the microtubule network controls chemotactic responses by regulating the balance between signals originating from the front and the back of neutrophils (Niggli, 2003a; Xu et al., 2005). As previously shown previously, we found that disruption of the microtubule network with 30 μM nocodazole leads to a small, but reproducible, fMLP-independent neutrophil polarization and migration, as measured using phalloidin staining and transwell assays (Figure 4C; data not shown). In accordance with this, we consistently observed a twofold increase in the basal AC activity in nocodazole-treated cells. Nevertheless, disruption of the microtubule network did not impair the ability of fMLP to further stimulate AC activity (Figure 4D). Together, these findings establish that the actin cytoskeleton does not regulate the chemoattractant-mediated stimulation of AC activity in neutrophils and show that changes in neutrophil polarity are not required to transduce the signals originating from chemoattractant receptors to AC. Furthermore, our findings suggest that microtubules may have a broad effect on chemattractant signaling, because their disruption gives rise to increase basal activity of AC as well as chemotaxis and F-actin levels.

We next evaluated the involvement of myosin II and Rho-associated protein kinases (ROCK) on AC activation. For these experiments we treated neutrophils with the myosin II inhibitor blebbistatin (100 μM) or the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μM) and assessed fMLP-mediated AC activation. As published previously, we found that both treatments gave rise to cells with multiple pseudopods and a general lost of uropod (data not shown) (Niggli, 2003a; Xu et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2005). However, neither drugs affected the extent by which fMLP stimulates AC activity (Figure 4, E and F). These findings suggest that the integrity of the back of neutrophils is not required for the chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC.

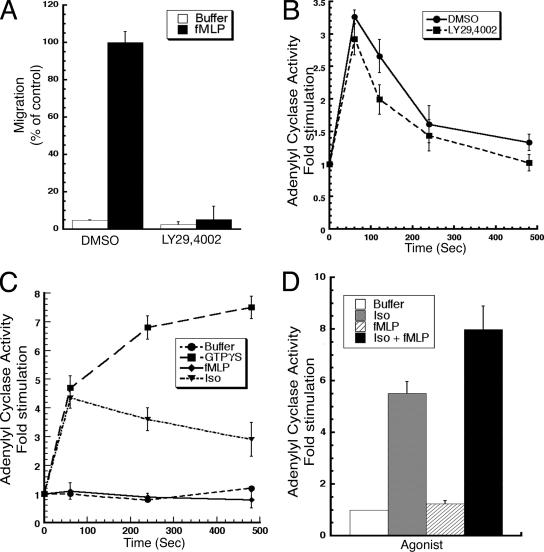

Chemoattractant Stimulation of Adenylyl Cyclase Is PI3K Independent but Requires Cellular Integrity

To further identify the signals involved in mediating the activation of AC by chemoattractants in neutrophils, we studied the role of PI3K in this response. Because the activation of the Dictyostelium ACA is dependent on PI3K activity, we reasoned that a similar pathway could also be operative in neutrophils (Comer et al., 2005). We treated neutrophils with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and assessed its efficiency by measuring the extent by which fMLP-mediated Akt/PKB phosphorylation and chemotaxis were inhibited. We determined that both responses were almost completely inhibited by pretreating neutrophils with 100 μM LY294002 for 30 min (Figure 5A; data not shown). In contrast, we found that similar treatment had no effect on fMLP-mediated AC activation (Figure 5B). Similar results were obtained with LTB4-mediated stimulation (data not shown). These findings establish that the signaling cascade that leads to the chemotactic activation of AC in neutrophils is independent of PI3K activity.

Figure 5.

Chemoattractant stimulation of AC is PI3K independent and requires cellular integrity. (A) Neutrophils were treated with or without 100 μM LY294002 for 30 min to inhibit PI3K activity, placed in a transwell chamber, and chemotaxis to 10 nM fMLP was assessed as described in the legend of Figure 1. (B) LY294002-treated and control cells were stimulated with 10 μM fMLP, and AC activity was assessed as described in the legend of Figure 1. Similar results were obtained with 50 nM fMLP (data not shown). (C) Neutrophils were filter lysed into a cup and stimulated with buffer, 100 μM GTPγ S, 100 μM isoproterenol, or 10 μM fMLP, and AC was measured as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Neutrophils were filter lysed into a cup and stimulated with buffer, 100 μM isoproterenol, 10 μM fMLP, or costimulated with 100 μM isoproterenol and 10 μM fMLP for 1 min and AC was measured as described in Materials and Methods.

To further study the mechanism by which chemoattractants stimulate AC activity, we determined the requirement for cellular integrity in the chemoattractant-mediated response. In Dictyostelium, the signaling cascade that leads to ACA activation is spatially restricted, and cell lysis disrupts the pathway involved in coupling the chemotactic signal to the downstream AC enzyme (Parent et al., 1998; Kriebel et al., 2003). We therefore assessed the ability of fMLP to activate AC in cell lysates. As positive controls, we used isoproterenol and GTPγS, which have been shown to rely exclusively on plasma membrane-associated components to activate AC (Neves et al., 2002). For these experiments, we filtered lysed cells into a cup and measured AC activity just before and following agonist addition. As expected, we observed that stimulation with either isoproterenol or GTPγS leads to a strong and persistent stimulation of AC activity in cell lysates (Figure 5C). In sharp contrast, no AC activation is measured after addition of fMLP (Figure 5C).

To rule out the possibility that chemoattractant receptor-G protein coupling is altered in neutrophil lysates, we performed costimulation experiments with isoproterenol and fMLP. We found that costimulation of lysates gives rise to a level of activation that is higher compared with the activation profile of isoproterenol alone (Figure 5D). We envision that in cell lysates, the Gβγ-subunits released after fMLP stimulation provides further positive input on the Gαs-mediated isoproterenol response leading to higher AC activity. Collectively, these results show that the chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC exhibits properties that are distinct from the canonical β-adrenergic, Gαs-mediated activation, which solely relies on plasma membrane-bound components.

DISCUSSION

We show that chemoattractant addition to human neutrophils gives rise to a rapid and transient activation of AC activity. Whereas chemoattractants, particularly fMLP, have previously been shown to increase total cAMP levels in neutrophils, the mechanism by which this occurs has remained unclear (Simchowitz et al., 1980; Smolen et al., 1980; Spisani et al., 1996; Suzuki et al., 1996; Ali et al., 1998). Cyclic AMP production is regulated by its synthesis through the activation of ACs and its degradation by phosphodiesterases. Neutrophil cAMP levels peak 15–30 s after exposure to fMLP and rapidly return to basal levels after 5 min (Simchowitz et al., 1980; Verghese et al., 1985). Pretreatment of neutrophils with phosphodiesterase inhibitors renders the cAMP elevation sustained and shifts the peak of accumulation to a plateau achieved at 60 s after fMLP stimulation (Simchowitz et al., 1980; Iannone et al., 1989). In addition, other chemokines such as C5a and LTB4 have been shown to elicit an increase in cAMP levels within neutrophils with similar kinetics (Simchowitz et al., 1980; Gorman et al., 1984). Using a pharmacological approach, it has been suggested that fMLP-stimulated cAMP accumulation is partly mediated by a transient inhibition of phosphodiesterase activity (Verghese et al., 1985). Whereas our studies do not address the impact of fMLP on phosphodiesterase activity, they clearly establish that chemoattractants activate AC. We were able to directly assess the effect of chemoattractants on AC activity by using an activation trap assay commonly used in Dictyostelium (Devreotes et al., 1987). Using filter lysis, this assay allows the rapid and accurate determination of AC activity after whole cell stimulation. We show that the activation is mediated via Gαiβγ, in a PI3K-independent manner, and it is lost when chemoattractants are added to cell lysate.

Our findings provide evidence that ACIX is the predominant AC isoform present in human neutrophils. We found that AC activity in neutrophil lysates is mostly forskolin insensitive, a property that is exclusively characteristic of ACIX (Premont et al., 1996; Hacker et al., 1998). The lack of reliable and specific antibodies against the AC isoforms precluded us from directly measuring protein levels. In a recent study, Chang et al. 2003 studied the AC expression profile in rat neutrophils. They showed that whereas all nine AC isoforms are expressed at the mRNA level, ACI, II, VI, and IX predominate (Chang et al., 2003). In addition, and in accordance with our findings using isoproterenol and forskolin, they observed that forskolin inhibits GTPγS stimulated cAMP accumulation. Similarly, it has been reported that forskolin attenuates GTPγS-mediated AC activation in membranes derived from guinea pig neutrophils as well as in HEK293 cells exogenously expressing ACIX (Suzuki et al., 1996; Hacker et al., 1998). These findings could be explained by the ability of forskolin to bind a novel, unknown, partner that specifically interferes with Gαs-mediated activation. However, because ACIX is the only AC known to exhibit this particular behavior in response to Gαs/forskolin costimulation when expressed in HEK293 cells, this explanation is unlikely. As previously proposed by Hacker et al. 1998, we favor a mechanism in which the binding of forskolin to ACIX renders the enzyme resistant to Gαs stimulation (Hacker et al., 1998). Because we also found that fMLP stimulation of AC is not altered by forskolin, we propose that signals downstream of chemotactic and β-adrenergic receptors act on distinct sites of ACIX.

Our findings establish that Gi-coupled signaling is required for chemoattractant-induced AC activity. At first glance, this result seems counterintuitive, because Gαi inhibits a subset of ACs (Sunahara and Taussig, 2002). However, because the four ACs expressed in neutrophils are insensitive to Gαi (Hacker et al., 1998; Sunahara and Taussig, 2002) and Gβγ-subunits do not activate ACs on their own (Tang and Gilman, 1991), we propose that chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC in neutrophils requires the released Gβγ subunits from Gαi, along with an additional factor having Gαs-like activity. Although basal Gαs activity could synergize with the Gβγ subunits released from Gαi to stimulate AC activity after neutrophil exposure to chemoattractants (Iannone et al., 1989), our studies suggest that another mechanism may be involved as well. Chemoattractant-mediated activation is specifically lost in cell lysates. Yet, under the same conditions, we are able to measure a synergistic effect on AC activity in the presence of fMLP and isoproterenol. Consequently, if such a Gαs/Gβγ synergy were at play during chemoattractant-mediated activation, it would have been detected in cell lysates. Instead, we envision that other components are involved. Interestingly, others have shown that chemoattractants use noncanonical pathways. Xenopus oocyte complementation studies revealed that coupling between fMLP or C5a receptors and calcium influx occurs only in oocytes preinjected with RNAs-derived from phagocytic cells (Murphy and McDermott, 1991; Schultz et al., 1992a,b). In addition, in sharp contrast to what is observed in neutrophils, fMLP stimulation of HEK293 cells engineered to express fMLP receptors leads to an inhibition of isoproterenol-mediated cAMP accumulation (Uhing et al., 1992). We have not thoroughly tested the requirement for small GTPases in the chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC; however, our findings with C. difficile toxin B establish that RhoGTPases are not required. Together, these observations suggest that neutrophils require unique factor(s) to transduce chemotactic signals to ACs.

Chemoattractant-mediated activation of the Dictyostelium adenylyl cyclase ACA, which shares homology with mammalian transmembrane ACs, requires cytosolic components (Kriebel and Parent, 2004). In these cells, chemoattractant receptors are coupled to the heterotrimeric G protein Gα2βγ. Genetic analyses revealed that cells lacking either Gα2- or Gβ-subunits do not exhibit chemoattractant-induced ACA activity. However, although the GTPγS-mediated activation of ACA is also lacking in gβ− cells, gα2− cells show a robust response to GTPγS, presumably mediated by the release of Gβγ subunits from G proteins other than Gα2βγ (Kesbeke et al., 1988; Wu et al., 1995; Parent and Devreotes, 1996; Kriebel and Parent, 2004). Such findings establish that, in Dictyostelium, Gα-subunits are not required for the chemoattractant-mediated activation of ACs. Instead, Gβγ-subunits work in concert with the pleckstrin homology (PH)-containing cytosolic regulator CRAC (Insall et al., 1994). On chemoattractant addition, CRAC is transiently recruited to the plasma membrane, in a PI3K-dependent manner (Parent et al., 1998; Comer et al., 2005). Although we have yet to determine the mechanism by which CRAC regulates ACA, we do know that the redistribution of CRAC to the plasma membrane, and PI3K activity, are essential (Comer et al., 2005; Comer and Parent, 2006). Extensive searches of the human, Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome data banks failed to identify CRAC homologues. Furthermore, the findings reported here show that AC activation does not seem to depend on PI3K activity. Together, these results exclude the requirement for a CRAC-like component for the chemoattractant-mediated activation of AC in neutrophils. Nevertheless, the striking homology of the chemoattractant-mediated AC activation profile between neutrophils and Dictyostelium, at the biochemical level, underscores the evolutionary conversation of the signaling cascades. Moreover, as the chemoattractant-mediated ACA activation also requires components of the TORC2 pathway (Chen et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1999, 2005), other novel factors may also be required in neutrophils.

In summary, our findings establish that, in neturophils, the pathway that links chemoattractant receptors/Gi to AC activation is fundamentally different from the canonical Gs to AC pathway. Moreover, it is similar to the well-characterized cascade leading to ACA activation in Dictyostelium. Additional studies will be required to identify the components required to transduce Gi-coupled signals to AC.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Phil Murphy and Joan Sechler for help with the neutrophil isolation procedure as well as the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the National Institutes of Health and the many donors for providing blood products. We also thank Drs. Pierre Coulombe, Alan Kimmel, Joe Brzostowski, and Lakshmi Balagopalan for reading the manuscript and making many helpful suggestions and the members of the Parent laboratory for reviewing the manuscript and for insightful discussions. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. D.C.M. is a recipient of a National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada postdoctoral fellowship. R.L.S. is a recipient of a Howard Hughes Medical Institute-National Institutes of Health Research Scholars Award.

Abbreviations used:

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- C5a

complement factor 5a

- fMLP

N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine

- GTPγS

guanosine 5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate

- LTB4

leukotriene B4

- PTX

pertussis toxin.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0418) on November 29, 2006.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

REFERENCES

- Ali H., Sozzani S., Fisher I., Barr A. J., Richardson R. M., Haribabu B., Snyderman R. Differential regulation of formyl peptide and platelet-activating factor receptors. Role of phospholipase Cβ3 phosphorylation by protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:11012–11016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariga M., Neitzert B., Nakae S., Mottin G., Bertrand C., Pruniaux M. P., Jin S. L., Conti M. Nonredundant function of phosphodiesterases 4D and 4B in neutrophil recruitment to the site of inflammation. J. Immunol. 2004;173:7531–7538. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature. 1998;392:565–568. doi: 10.1038/33340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M., Moser B., Clark-Lewis I. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines. The Giles Filley Lecture. Chest. 1994;105:95S–98S. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.3_supplement.95s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagorda A., Mihaylov V. A., Parent C. A. Chemotaxis: moving forward and holding on to the past. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;95:12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoni F., Cassatella M. A., Rossi F., Ceska M., Dewald B., Baggiolini M. Phagocytosing neutrophils produce and release high amounts of the neutrophil-activating peptide 1/interleukin 8. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:771–774. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyum A. Separation of blood leucocytes, granulocytes and lymphocytes. Tissue Antigens. 1974;4:269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L. C., Wang C. J., Lin Y. L., Wang J. P. Expression of adenylyl cyclase isoforms in neutrophils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1640:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. Y., Long Y., Devreotes P. N. A novel cytosolic regulator, Pianissimo, is required for chemoattractant receptor and G protein-mediated activation of the 12 transmembrane domain adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3218–3231. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer F. I., Lippincott C. K., Masbad J. J., Parent C. A. The PI3K-mediated activation of CRAC independently regulates adenylyl cyclase activation and chemotaxis. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer F. I., Parent C. A. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity controls the chemoattractant-mediated activation and adaptation of adenylyl cyclase. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:357–366. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devreotes P., Fontana D., Klein P., Sherring J., Theibert A. Transmembrane signaling in Dictyostelium. Methods Cell Biol. 1987;28:299–331. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61653-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinauer M. C., Steck T. L., Devreotes P. N. Cyclic 3′,5′-AMP relay in Dictyostelium discoideum. V. Adaptation of the cAMP signaling response during cAMP stimulation. J. Cell Biol. 1980;86:554–561. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elferink J. G., VanUffelen B. E. The role of cyclic nucleotides in neutrophil migration. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996;27:387–393. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman R. R., Lin A. H., Hopkins N. K. Acetylglycerylether phosphorylcholine-(AGEPC) and leukotriene B4-stimulated cyclic AMP levels in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation Res. 1984;17:631–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker B. M., Tomlinson J. E., Wayman G. A., Sultana R., Chan G., Villacres E., Disteche C., Storm D. R. Cloning, chromosomal mapping, and regulatory properties of the human type 9 adenylyl cyclase (ADCY9) Genomics. 1998;50:97–104. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. Calcium-sensing soluble adenylyl cyclase mediates TNF signal transduction in human neutrophils. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:353–361. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvath L., Robbins J. D., Russell A. A., Seamon K. B. cAMP and human neutrophil chemotaxis. Elevation of cAMP differentially affects chemotactic responsiveness. J. Immunol. 1991;146:224–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe A. K., Hogan B. P., Juliano R. L. Regulation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein phosphorylation and interaction with Abl by protein kinase A and cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:38121–38126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannone M. A., Wolberg G., Zimmerman T. P. Chemotactic peptide induces cAMP elevation in human neutrophils by amplification of the adenylate cyclase response to endogenously produced adenosine. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:20177–20180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insall R., Kuspa A., Lilly P. J., Shaulsky G., Levin L. R., Loomis W. F., Devreotes P. CRAC, a cytosolic protein containing a pleckstrin homology domain, is required for receptor and G protein-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:1537–1545. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S. Amplification of extracellular nucleotide-induced leukocyte(s) degranulation by contingent autocrine and paracrine mode of leukotriene-mediated chemokine receptor activation. Med. Hypotheses. 2002;59:261–265. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(02)00213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesbeke F., Snaar-Jagalska B. E., Van Haastert P. J. Signal transduction in Dictyostelium fgd A mutants with a defective interaction between surface cAMP receptors and a GTP-binding regulatory protein. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:521–528. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel P. W., Barr V. A., Parent C. A. Adenylyl cyclase localization regulates streaming during chemotaxis. Cell. 2003;112:549–560. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel P. W., Parent C. A. Adenylyl cyclase expression and regulation during the differentiation of Dictyostelium discoideum. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:541–546. doi: 10.1080/15216540400013887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Comer F. I., Sasaki A., McLeod I. X., Duong Y., Okumura K., Yates J. R., 3rd, Parent C. A., Firtel R. A. TOR complex 2 integrates cell movement during chemotaxis and signal relay in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:4572–4583. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Parent C. A., Insall R., Firtel R. A. A novel Ras-interacting protein required for chemotaxis and cyclic adenosine monophosphate signal relay in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:2829–2845. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.9.2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly P. J., Devreotes P. N. Chemoattractant and GTPγS-mediated stimulation of adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium requires translocation of CRAC to membranes. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:1659–1665. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig K. D., Conklin B. R., Herzmark P., Taussig R., Bourne H. R. Type II adenylylcyclase integrates coincident signals from Gs, Gi, and Gq. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:13900–13905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming G. L., Song H. J., Berninger B., Holt C. E., Tessier-Lavigne M., Poo M. M. cAMP-dependent growth cone guidance by netrin-1. Neuron. 1997;19:1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P. M. Chemokine receptors: structure, function and role in microbial pathogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7:47–64. doi: 10.1016/1359-6101(96)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P. M., McDermott D. Functional expression of the human formyl peptide receptor in Xenopus oocytes requires a complementary human factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:12560–12567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves S. R., Ram P. T., Iyengar R. G protein pathways. Science. 2002;296:1636–1639. doi: 10.1126/science.1071550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niggli V. A membrane-permeant ester of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP(3)) is an activator of human neutrophil migration. FEBS Lett. 2000;473:217–221. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niggli V. Microtubule-disruption-induced and chemotactic-peptide-induced migration of human neutrophils: implications for differential sets of signalling pathways. J. Cell Sci. 2003a;116:813–822. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niggli V. Signaling to migration in neutrophils: importance of localized pathways. Int. J. Biochem.Cell Biol. 2003b;35:1619–1638. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor K. L., Nguyen B. K., Mercurio A. M. RhoA function in lamellae formation and migration is regulated by the a6b4 integrin and cAMP metabolism. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:253–258. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor K. L., Shaw L. M., Mercurio A. M. Release of cAMP gating by the a6b4 integrin stimulates lamellae formation and the chemotactic migration of invasive carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1749–1760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent C. A. Making all the right moves: chemotaxis in neutrophils and Dictyostelium. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent C. A., Blacklock B. J., Froehlich W. M., Murphy D. B., Devreotes P. N. G protein signaling events are activated at the leading edge of chemotactic cells. Cell. 1998;95:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent C. A., Devreotes P. N. Molecular genetics of signal transduction in Dictyostelium. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:411–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premont R. T., Matsuoka I., Mattei M. G., Pouille Y., Defer N., Hanoune J. Identification and characterization of a widely expressed form of adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:13900–13907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon Y. Adenylate cyclase assay. Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide. Res. 1979;10:35–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saran S., Meima M. E., Alvarez-Curto E., Weening K. E., Rozen D. E., Schaap P. cAMP signaling in Dictyostelium. Complexity of cAMP synthesis, degradation and detection. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2002;23:793–802. doi: 10.1023/a:1024483829878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz P., Stannek P., Bischoff S. C., Dahinden C. A., Gierschik P. Functional reconstitution of a receptor-activated signal transduction pathway in Xenopus laevis oocytes using the cloned human C5a receptor. Cell Signal. 1992a;4:153–161. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(92)90079-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz P., Stannek P., Voigt M., Jakobs K. H., Gierschik P. Complementation of formyl peptide receptor-mediated signal transduction in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biochem. J. 1992b;284:207–212. doi: 10.1042/bj2840207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simchowitz L., Fischbein L. C., Spilberg I., Atkinson J. P. Induction of a transient elevation in intracellular levels of adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate by chemotactic factors: an early event in human neutrophil activation. J. Immunol. 1980;124:1482–1491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen J. E., Korchak H. M., Weissmann G. Increased levels of cyclic adenosine-3′,5′-monophosphate in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes after surface stimulation. J. Clin. Investig. 1980;65:1077–1085. doi: 10.1172/JCI109760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spisani S., Pareschi M. C., Buzzi M., Colamussi M. L., Biondi C., Traniello S., Pagani Zecchini G., Paglialunga Paradisi M., Torrini I., Ferretti M. E. Effect of cyclic AMP level reduction on human neutrophil responses to formylated peptides. Cell Signal. 1996;8:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(96)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara R. K., Taussig R. Isoforms of mammalian adenylyl cyclase: multiplicities of signaling. Mol. Interv. 2002;2:168–184. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Hazeki O., Hazeki K., Ui M., Katada T. Involvement of the beta gamma subunits of inhibitory GTP-binding protein in chemoattractant receptor-mediated potentiation of cyclic AMP formation in guinea pig neutrophils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1313:72–78. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(96)00048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. J., Gilman A. G. Type-specific regulation of adenylyl cyclase by G protein bg subunits. Science. 1991;254:1500–1503. doi: 10.1126/science.1962211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. J., Hurley J. H. Catalytic mechanism and regulation of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;54:231–240. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhing R. J., Gettys T. W., Tomhave E., Snyderman R., Didsbury J. R. Differential regulation of cAMP by endogenous versus transfected formylpeptide chemoattractant receptors: implications for Gi-coupled receptor signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;183:1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhing R. J., Snyderman R. Chemoattractant stimulus-response coupling. In: Gallin J. I., Snyderman R., Fearon D. T., Haynes B. F., N. C., editors. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams ' Wilkins; 1999. pp. 607–638. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haastert P. J., Devreotes P. N. Chemotaxis: signalling the way forward. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:626–634. doi: 10.1038/nrm1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanUffelen B. E., de Koster B. M., Elferink J. G. Interaction of cyclic GMP and cyclic AMP during neutrophil migration: involvement of phosphodiesterase type III. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;56:1061–1063. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese M. W., Fox K., McPhail L. C., Snyderman R. Chemoattractant-elicited alterations of cAMP levels in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes require a Ca2+-dependent mechanism which is independent of transmembrane activation of adenylate cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:6769–6775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner O. D., Neilsen P. O., Prestwich G. D., Kirschner M. W., Cantley L. C., Bourne H. R. A PtdInsP(3)- and Rho GTPase-mediated positive feedback loop regulates neutrophil polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:509–513. doi: 10.1038/ncb811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Valkema R., Van Haastert P. J., Devreotes P. N. The G protein b subunit is essential for multiple responses to chemoattractants in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:1667–1675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Wang F., Van Keymeulen A., Herzmark P., Straight A., Kelly K., Takuwa Y., Sugimoto N., Mitchison T., Bourne H. R. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils. Cell. 2003;114:201–214. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Wang F., Van Keymeulen A., Rentel M., Bourne H. R. Neutrophil microtubules suppress polarity and enhance directional migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6884–6889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502106102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.