Abstract

We use asexual development of Neurospora crassa as a model system with which to determine the causes of cell differentiation. Air exposure of a mycelial mat induces hyphal adhesion, and adherent hyphae grow aerial hyphae that, in turn, form conidia. Previous work indicated the development of a hyperoxidant state at the start of these morphogenetic transitions and a large increase in catalase activity during conidiation. Catalase 3 (CAT-3) increases at the end of exponential growth and is induced by different stress conditions. Here we analyzed the effects of cat-3-null strains on growth and asexual development. The lack of CAT-3 was not compensated by other catalases, even under oxidative stress conditions, and cat-3RIP colonies were sensitive to H2O2, indicating that wild-type (Wt) resistance to external H2O2 was due to CAT-3. cat-3RIP colonies grown in the dark produced high levels of carotenes as a consequence of oxidative stress. Light exacerbated oxidative stress and further increased carotene synthesis. In the cat-3RIP mutant strain, increased aeration in liquid cultures led to increased hyphal adhesion and protein oxidation. Compared to the Wt, the cat-3RIP mutant strain produced six times more aerial hyphae and conidia in air-exposed mycelial mats, as a result of longer and more densely packed aerial hyphae. Protein oxidation in colonies was threefold higher and showed more aerial hyphae and conidia in mutant strains than did the Wt. Results indicate that oxidative stress due to lack of CAT-3 induces carotene synthesis, hyphal adhesion, and more aerial hyphae and conidia.

We study cell differentiation by using the asexual life cycle of Neurospora crassa as a model system. There is a wealth of information about the genetics, biochemistry, physiology, and cellular and molecular biology of N. crassa, and its genome has been recently sequenced by the Whitehead Institute/MIT Center for Genome Research (www-genome.wi.mit.edu) (10a).

A synchronous process of asexual spore (conidium) formation is started when an aerated liquid culture is filtered and the resulting mycelial mat is exposed to air (35, 38). Filaments (hyphae) in direct contact with air adhere to each other within 40 min, adherent mycelium starts growing aerial hyphae after 2 h, and conidia are formed at the tips of the branched aerial hyphae after 8 to 9 h of air exposure (38). Thus, formation of conidia from growing hyphae involves three morphogenetic transitions: growing hyphae to adherent mycelium; adherent mycelium to aerial hyphae; and aerial hyphae to conidia.

A hyperoxidant state develops at the start of these morphogenetic transitions (14, 39-42) and during germination of conidia (26). A hyperoxidant state is defined as an unstable, transient state in which reactive oxygen species surpass the antioxidant capacity of the cell (13, 15). The occurrence of a hyperoxidant state is indicated by oxidation of total protein that occurs at the start of the aforementioned morphogenetic transitions (39, 41). Glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase oxidation occurs during adhesion of hyphae, formation of aerial hyphae, and return to the growth state (41, 42). Catalase is modified during conidiation (15) and in vitro because of the reaction of singlet oxygen (1O2) with its heme (25). Also, during germination of conidia, total protein oxidation and catalase oxidation by 1O2 increases with light, a source of 1O2, or insufficient 1O2 quenching by carotenes (26).

In studies on the activity of antioxidant enzymes during the asexual life cycle of N. crassa, large differences in catalase specific activity were observed. There was a stepwise increase in catalase activity during the process that leads to formation of conidia. In fact, conidia have 60 times more catalase activity than hyphae growing in liquid medium (15, 30). Catalase 3 (CAT-3) and CAT-1 constitute the main catalase activities and are differentially regulated during the N. crassa asexual life cycle. CAT-3 activity increases during exponential growth and is induced by different stress conditions (30); CAT-1 increases at the stationary growth phase and is accumulated in conidia (8, 30).

Most of the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in cells comes from superoxide (O2·−) dismutation. O2·− arises mainly by electron leakage from the respiratory chain and from the activity of enzymes, such as NADPH oxidase and other oxidases. O2·− is dismutated by O2·− dismutase (SOD) to form H2O2 and dioxygen (O2). There is a cytosolic, a mitochondrial, and usually an extracellular SOD. There is also a high redundancy of enzymes for the disposition of H2O2: catalases, catalase/peroxidases, peroxidases, and peroxiredoxins. When O2·− and H2O2 disposal is insufficient, hydroxyl radical (HO·) is formed from H2O2 reduction by metal ions and 1O2 is generated by spontaneous dismutation of O2·− , metal-catalyzed reaction of O2·− with H2O2, and decomposition of H2O2 by different compounds (reviewed in reference 27). Instead, in the presence of SOD and catalase, O2·− and H2O2 are converted quantitatively into water and O2. Thus, disposal of O2·− and H2O2 is vital to avoid formation of highly reactive HO· and 1O2.

Induction of antioxidant mechanisms is an expected consequence of a hyperoxidant state and explains the increase in catalase activity in our model system. Many other microorganisms have more than one catalase, and in some of them, a catalase is related to cell differentiation (2, 10, 17, 19, 20, 28, 31, 46). This does not imply that catalases are essential for cell differentiation. Because of its importance for cell survival, there is ample redundancy in antioxidant mechanisms. Nullification of different antioxidant enzymes is probably required to impair conidiation in N. crassa, and this will probably lead to cell death. However, if cell differentiation is a response to a hyperoxidant state, nullification of an antioxidant enzyme should lead to increased oxidative stress and increased cell differentiation.

Here we analyzed the effect of cat-3 inactivation on asexual development. cat-3-null mutant strains tend to develop oxidative stress, measured by protein oxidation, and react by increasing carotenes levels and cell adhesion and development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

N. crassa strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Wild type (Wt) strains 74-ORS23-1A and ORS-SL6-a and his-3 mutant strain 6103A were obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center. The his-3 mutant strain contains a single mutation in a gene encoding a multifunctional enzyme for histidine biosynthesis. Plasmid pDE1, containing a truncated his-3 gene, was used to direct cat-3 integration to this locus (9).

Liquid cultures were grown in Vogel's minimal medium (VM) containing 1.5 or 2% sucrose from an inoculum of 105 to 106 conidia/ml at an air/liquid ratio of 3:2, and incubated at 30°C with agitation at 200 or 250 rpm for 12 to 16 h. For the his-3 mutant, the growth medium was supplemented with 200 μg of l-histidine per ml.

To impose oxidative stress, mycelium gown from an inoculum of 3 × 105 conidia/ml was harvested by filtration after 14 h of growth, washed briefly with fresh medium, and transferred to growth medium containing either 1 mM H2O2, 30 mM CaCO3, or 5 mM paraquat. Mycelia were recovered after 0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h, and catalase activity in cell extracts was determined.

Conidia were isolated from solid cultures with VM, supplemented with 1.5% sucrose and 1.5% agar, in Erlenmeyer flasks. Cultures were inoculated with conidia, and incubated for 3 days at 30°C in the dark and then for 2 days at 25°C in the light. To grow colonies, petri dishes with 1.5% agar in VM supplemented with 0.05% fructose, 0.05% glucose, and 2% sorbose (VSM) (6) were inoculated with 200 to 250 conidia and incubated at 30°C for 3 or 7 days. When colonies were isolated, a cellophane sheet was layered onto solid cultures in petri dishes before plating of conidia. Cellophane was washed and autoclaved in distilled water. Illumination of colonies in petri plates was done with a 500-W tungsten bulb at a distance of 50 cm (5 W/cm2) for 1 h.

Treatment with H2O2 was done in solid cultures inoculated with 250 conidia and incubated at 30°C, and 2 days later, 10 ml of either 5, 10, 15, or 20 mM H2O2 was added to each culture. After a 10-min treatment, the H2O2 was discarded and incubation was continued for 2 more days. Colony counts were determined and compared with those of untreated controls.

Hyphal adhesion was determined at different air/liquid ratios in 25-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 5, 10, 15, or 20 ml of a growth medium inoculated with 3 × 105 conidia/ml and grown for 15 h at 30°C and 250 rpm. Cultures were photographed, and mycelia were harvested by filtration to determine protein oxidation. To measure the amount of aerial hyphae and conidia, liquid cultures inoculated with 106 conidia/ml were incubated for 16 h at 30°C and 200 rpm. One hundred milliliters of culture was filtered, and the resulting mycelial mat inside petri dishes was exposed to air for 24 h at room temperature. Aerial mycelia were recovered with a spatula, vacuum dried, and weighed. To measure the height and density of aerial hyphae, we took advantage of the ability of aerial hyphae to stick to glass. Microscope slides standing on mycelial mats were removed after different times of aerial growth. The height and area covered by aerial hyphae were determined, conidiation was analyzed under a light microscope, and the protein in detached aerial hyphae was measured. The height and density of aerial hyphae sticking to the slides was also determined by using 2.5-ml liquid cultures in 50-ml Falcon tubes with the slide in the tube only touching the culture surface. For determination of conidial counts, 1 ml of sterile water was added to harvested aerial mycelium and agitated in a Vortex mixer for 5 min, and free conidia were counted with a Neubauer chamber. Conidia in colonies were determined in 20 randomly picked colonies and counted as indicated. To show increased aerial hyphae, some mats were covered with darkly stained filter paper. Aerial hyphae grew through the stained filter, and cultures were photographed after 24 h of development.

Disruption of cat-3.

Two primer oligonucleotides, each containing an EcoRI restriction site (5′-CGCCGAATTCATGCGTGTCAACGCTCTT-3′ and 5′CCCGAATTCTTACTCCTCATCATCGC-3′) were used to amplify the cat-3 cDNA sequence from plasmid pSM1 by PCR. The amplified 2-kb cat-3 cDNA sequence was cloned by replacing the lacZ EcoRI fragment in plasmid pDE1 (9), yielding pSM3. The truncated N. crassa his-3 gene in the plasmid was used to direct integration to this locus. Forty microliter of 1.25 × 1010 conidia/ml from his-3 mutant strain FGSC 6103 was electroporated at 1.5 kV with circular pSM3 (500 μg) (29). Histidine prototrophs were isolated and analyzed by DNA blot hybridization to select transformants with the cat-3 sequence adjacent to the repaired his-3 locus. After three cycles of single-colony isolation, a transformant was crossed to the Wt strain to obtain his-3 prototrophs lacking the cat-3 transcript the and CAT-3 protein.

Vegetative mycelia were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until used. Total RNA was isolated with TRIZOL (GIBCO, BRL) in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer. For Northern blot assays, 10 μg of RNA per lane was loaded onto a 0.7% agarose gel containing formaldehyde, run at 60 V, transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond-N; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and hybridized with a cat-3 probe. Genomic DNA was isolated as described by Vollmer and Yanofsky (45). For Southern blot assays, 5 μg of DNA was digested with 20 U of MscI, electrophoresed on an agarose gel, transferred to Hybond-XL membrane (Amersham RPN 203 S), fixed to the membrane with UV light (UV Stratalinker 1800; Stratagene), and hybridized with a cat-3 or his-3 probe. Radioactivity was detected by autoradiography with Kodak Biomax MR film.

Sexual crosses were performed on synthetic cross medium as described by Davis and De Serres (6).

Protein isolation.

Mycelia were harvested by filtration and resuspended in 1 ml of acetone, agitated for 15 s in a Vortex mixer, and centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 × g. Acetone was eliminated, and the precipitate was dried by evaporation. One hundred milligrams of the dry pellet was resuspended in 300 μl of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM desferrioxamine B mesylate. Hyphae were broken by agitation with 100 mg of glass beads (710 to 1,180 μm) in a Vortex mixer for 30 min at 4°C. Protein was determined by the method of Bradford or Lowry et al.

For detection of secreted CAT-3 in liquid medium after 16 h growth, mycelia were separated by filtration and 1 liter of growth medium was dialyzed against distilled water, concentrated in an Amicon YM100 to 1 ml, precipitated with 2 volumes of acetone, and resuspended in 300 μl of HEPES-phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride-dithiothreitol-desferrioxamine B mesylate buffer.

CAT-3 activity and immunodetection.

Catalase (hydrogen peroxide:hydrogen peroxide oxidoreductase; EC 1.11.1.6) activity was either measured by determining the initial rate of O2 production with a Clark microelectrode or detected in gels after polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (25). For determination of catalase activity, PAGE under nondenaturing conditions was used, usually with loading of 50 U of catalase activity or 30 μg of protein in each lane. Minigels of 8 by 9 cm and 0.75 cm thick with 8% polyacrylamide and 0.2% bisacrylamide were made in accordance with the Laemmli procedure but without sodium dodecyl sulfate and β-mercaptoethanol and without boiling of the samples. For CAT-3 immunodetection, denaturing conditions were used. After PAGE, gels were immediately used for immunodetection or stained for catalase activity. Two-dimensional (2-D) PAGE was done as described before (25). For immunodetection, proteins were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose filters (Gibco BRL) at 100 V for 1 h with a Mighty Small Transfer unit (Hoefer) and the buffer described by Towbin et al. (43). Filters were blocked with 3% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline-Tween 20 (0.03%) buffer at room temperature and then incubated with rabbit sera containing polyclonal anti-CAT-3 or anti-CAT-1 antibodies diluted as appropriate in phosphate-buffered saline-Tween 20-0.1% skim milk. Antibodies were detected with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G coupled to horseradish peroxidase and developed with 4-chloro-1-naphthol as the substrate.

Carotenoid extraction and determination.

Three-day-old colonies (n = 250) growing over cellophane on solid cultures were illuminated for 1 h with intense light (5 W/cm2) and immediately recovered with a spatula. Colonies were resuspended in 400 μl of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, and broken by agitation in an Eppendorf tube with 300 mg of glass beads at the Vortex mixer's maximal speed at 4°C for 30 min. Carotenoids were extracted from 400 μl of cell extract, containing 4 mg of protein, with 400 μl of butanol-chloroform (1:3 vol/vol). The mixture was stirred for 2 min in a Vortex mixer at full speed and thereafter centrifuged in a microcentrifuge. The butanol-chloroform phase, containing most of the carotenoids, was recovered and diluted 50 times with butanol-chloroform, and spectra were run in a Beckman spectrometer.

Carbonyl content in total protein.

Liquid-grown mycelium was harvested by filtration and dried with acetone. Protein was extracted as mentioned above, and carbonyl content was determined as described by Ahn et al. (1), but the extraction with butanol-chloroform was repeated six times to ensure the elimination of all lipids (carotenes). Colonies (n = 150) on cellophane-overlaid solid cultures with VSM were grown for 3 or 7 days in the dark at 30°C. Colonies were recovered with a spatula and dried with acetone. Protein was extracted from five colonies in 300 μl of buffer, and carbonyl content was determined as described above.

RESULTS

Disruption of cat-3.

During meiosis in N. crassa, chromosomal sequences that are repeated in the haploid genome are mutated through a process called repeat-induced point mutation (RIP). In this process, methylation of cytosines generate C-to-T and G-to-A transitions that inactivate every repeated sequence (4). RIP has been used with great success to generate null mutants of N. crassa by introducing a copy of the gene to be disrupted into the genome and crossing the transformed strain.

A 2-kb fragment of cat-3 cDNA was cloned into a plasmid containing an N-terminally truncated his-3 gene and used to transform an N. crassa histidine auxotroph containing a point mutation in the his-3 locus. Histidine prototrophs were isolated and analyzed by DNA blot hybridization to select transformants containing cat-3 sequence adjacent to the repaired his-3 locus. After three cycles of single-colony isolation, a transformant was crossed to the Wt strain to obtain his-3 prototrophs with no cat-3 transcript or CAT-3 protein. Twenty of the 42 randomly picked progeny colonies were CAT-3 defective, indicating 1:1 segregation. The phenotype of two of them, cat-351 and cat-360, mating type A, was characterized in more detail and compared to the Wt strain.

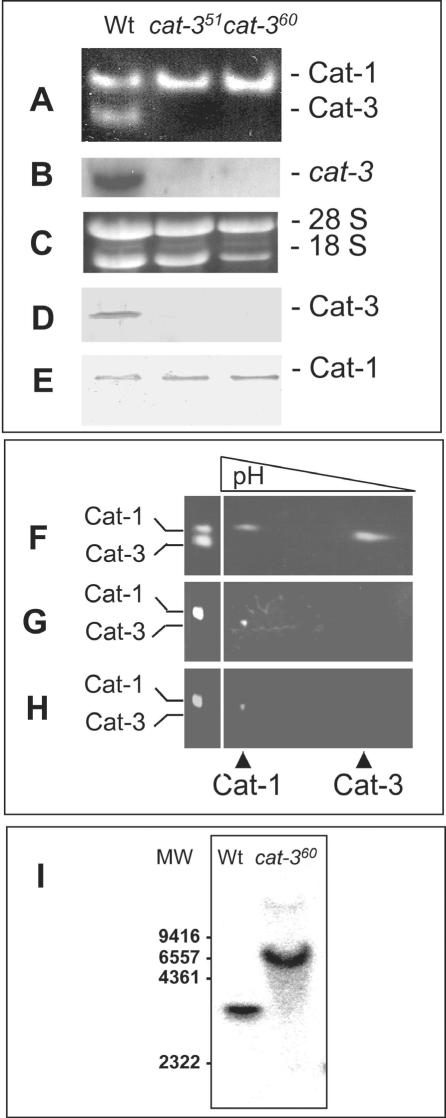

No CAT-3 activity (Fig. 1A) or cat-3 transcript (Fig. 1B) was detected in either mutant stain. In addition, no CAT-3 antigen was detected with polyclonal antibodies directed against purified CAT-3 (Fig. 1D). As a control, CAT-1 antigen was detected in similar amounts in the Wt and CAT-3 mutant strains (Fig. 1E). To further confirm the absence of CAT-3 and possible mutant peptides with catalase activity, 2-D PAGE was performed. Only CAT-1 was detected in cat-351 (Fig. 1G) and cat-360 mutant strains (Fig. 1H).

FIG. 1.

cat-3-null strains lack cat-3 transcript and CAT-3 protein. (A) Catalase activity in gels after PAGE under nondenaturing conditions of 30 μg of protein extract from the Wt and cat-351 and cat-360 mutant strains. (B) Autoradiography of total RNA (10 μg) isolated from growing Wt or cat-351 or cat-360 mutant mycelia hybridized with a radioactive cat-3 probe. (C) Ethidium bromide staining of the gel used in panel B to evaluate RNA loading. (D and E) Immunodetection of CAT-3 and CAT-1 in Wt and cat-351 and cat-360 mutant cell extracts. Polyclonal antibodies that specifically recognize CAT-3 or CAT-1 were used and developed with a peroxidase-bound anti-rabbit antibody. (F to H) Catalase activity in gels after 2-D PAGE of Wt (F) or cat-351 (G) or cat-360 (H) mutant cell extracts. (I) Southern blot analysis of DNAs from Wt and cat-360 mutant cells digested with MscI and hybridized with a radioactive cat-3 probe; phage λ DNA digested with HindIII was used as molecular weight (MW) standards.

To prove that the lack of CAT-3 was due to RIP, the cat-360 mutant and Wt DNAs were digested with different restriction enzymes that are sensitive to DNA methylation and analyzed by DNA blot hybridization with cat-3 as the probe. With MscI, cat-3 hybridized to a DNA fragment from cat-360 with a higher molecular weight, consistent with loss of the single MscI site in the gene (Fig. 1I).

CAT-3 loss is not compensated for by other catalases, and mutant strains are H2O2 sensitive.

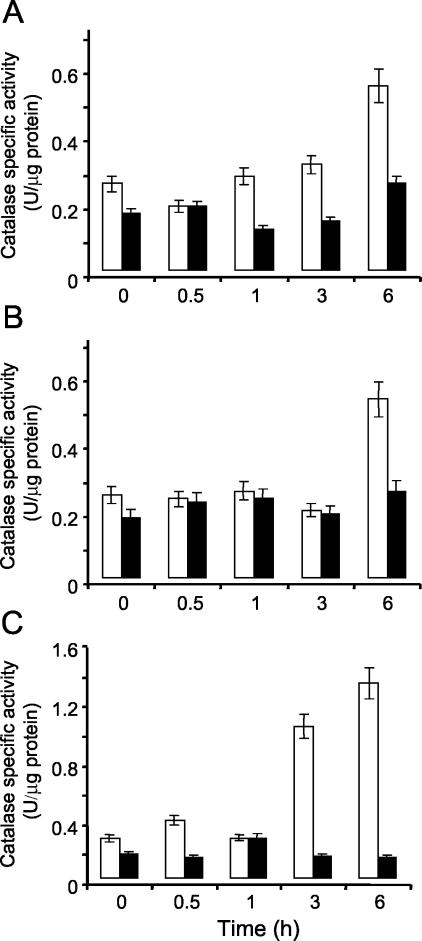

Because N. crassa has three monofunctional catalases and one catalase/peroxidase (31a), increasing the activity of another catalase could compensate for the lack of CAT-3 in the mutant strains. Previous experiments indicated that H2O2, CaCO3, and particularly paraquat induced cat-3 transcript and CAT-3 activity levels (30). We assayed total catalase activity in liquid cultures subjected to these oxidative stress conditions: in cat-3RIP strains, with or without stress, total catalase activity remained at similar levels (Fig. 2A to C); in the Wt strain, 6 h of stress led to a twofold increase in catalase activity under the first two conditions (Fig. 2A and B) and a seven- to eightfold increase with paraquat (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that the lack of CAT-3 was not compensated for by other catalases.

FIG. 2.

Lack of CAT-3 activity in a cat-3-null mutant strain is not compensated for by other catalases. Wt (white bars) and cat-360 mutant (dark bars) mycelia grown for 14 h were transferred to fresh medium containing 1 mM H2O2 (A), 30 mM CaCO3 (B), or 5 mM paraquat (C). After 0.5, 1, 3, or 6 h of treatment, catalase activity was determined in cell extracts. The results shown are averages of three independent experiments.

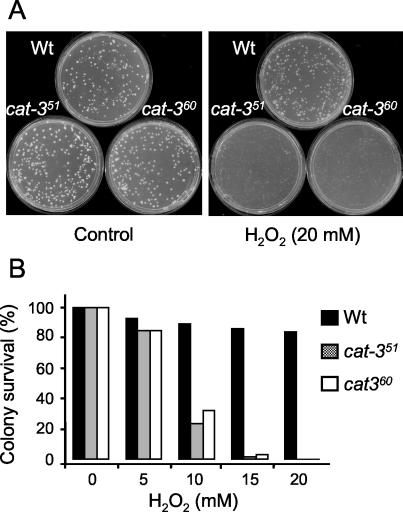

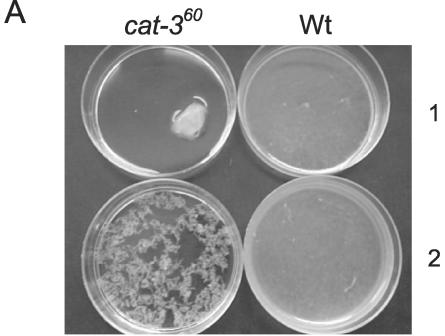

Other H2O2-disposing enzymes such as peroxiredoxins and/or peroxidases could also have a compensating effect. To analyze the H2O2 sensitivity of the cat-3RIP strains, 20 mM H2O2 was added to 2-day-old colonies grown in petri dishes. H2O2 was eliminated after 10 min, and colony survival was analyzed 2 days later. cat-3RIP strains did not resist this treatment, while the Wt strain seemed unaffected (Fig. 3A). Similar assays with 5 to 20 mM H2O2 concentrations showed a dose-response effect. At 10 mM H2O2, only 25 to 30% of the cat-3 colonies survived, compared to more than 90% of the Wt colonies (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

cat-3-null mutant strains are sensitive to H2O2. Wt or cat-351 or cat-360 mutant conidia (n = 250) were plated on VSM, and after 2 days, colonies were covered with an H2O2 solution. After a 10-min treatment, the H2O2 solution was discarded and the plates were incubated for another 2 days. Thereafter, colonies were counted and compared to untreated controls. (A) Plates of Wt and mutant strain colonies after treatment with 20 mM H2O2. (B) Percentages of colonies that survived H2O2 treatment at the indicated concentrations.

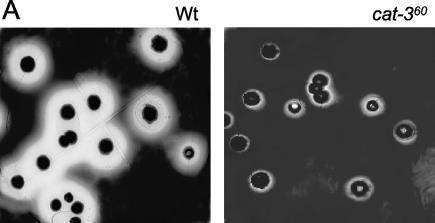

CAT-3 is secreted.

CAT-3 has an N-terminal signal peptide that is processed (30) and probably used for enzyme secretion, as was found for homologous catalases (3, 12). To find out if CAT-3 is secreted, we stained colonies in petri dishes for catalase activity. A large halo of catalase activity observed in Wt colonies was absent or strongly reduced in the cat-360 strain (Fig. 4A), suggesting that CAT-3 activity diffuses out of colonies.

FIG. 4.

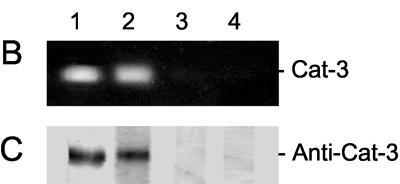

CAT-3 is secreted. Panels: A, plates with 4-day-old Wt or cat-360 mutant colonies stained for catalase activity; B, CAT-3 activity; C, immunodetection of CAT-3. Purified CAT-3 (lane 1) and total protein from the Wt (lane 2) and cat-351 (lane 3) and cat-360 (lane 4) mutant growth media after PAGE under nondenaturing conditions are shown. After transfer to nitrocellulose filters, CAT-3-specific polyclonal antibodies were detected by the activity of peroxidase-bound anti-rabbit antibodies.

To confirm CAT-3 secretion, the liquid medium in which Wt or mutant strains grew for 16 h was dialyzed, concentrated, and analyzed for CAT-3 activity and protein. CAT-3 activity (Fig. 4B) and immunodetected CAT-3 protein (Fig. 4C) were recovered from the growth medium of the Wt strain but not from that of the cat-3RIP mutant strains. These results demonstrate that CAT-3 is secreted.

cat-3 mutants show increased carotene content in the dark and after exposure to a pulse of light.

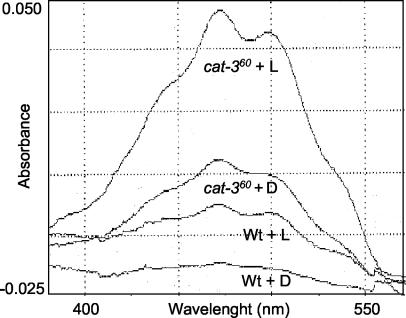

Colonies of cat-3-null mutants were more pigmented than the Wt. Pigmentation in N. crassa is mainly due to carotenes. Carotene synthesis is induced by oxidative stress and by light. Carotene content was measured in 3-day-old colonies grown in the dark or grown in the dark and then illuminated for 1 h at 5 W/cm2. In the dark, almost no carotenes were detected in Wt colonies; however, the carotene level was 7.7-fold higher in the cat-360 mutant strain (Fig. 5), denoting increased oxidative stress in that strain. Upon illumination, the total carotene content increased 4.8- and 2.3-fold in the Wt and mutant strains, respectively. Even under these conditions, the cat-360 mutant strain still had 3.7 times more carotenes than did the Wt (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Carotene contents of Wt and cat-360 mutant colonies. Spectra of isolated carotenes from cell extracts containing 4 mg of protein. Three-day-old Wt and cat-360 colonies, grown in the dark on cellophane-covered solid medium, were illuminated for 1 h with intense light (5 W/cm2), and carotenes were immediately extracted (Wt + L and cat-360 + L). Control plates were also illuminated but wrapped with aluminum foil (Wt + D and cat-360 + D). The results of an experiment representative of the four independent experiments performed are shown.

Increased hyphal adhesion and protein oxidation in the cat-3 mutant.

Hyphal adhesion is dependent on air and is the first morphogenetic step toward the conidiation process. Aerial hyphae in a mycelial mat develop only from a layer of adherent hyphae (38). Hyphal adhesion can also be observed in liquid cultures under oxidative stress conditions, such as increased aeration (i.e., an increase in the air-to-liquid ratio). To analyze hyphal adhesion in cat-3RIP mutant strains, liquid medium was inoculated with conidia and distributed among 25-ml Erlenmeyer flasks at different air-to-liquid ratios. Adhesion of Wt hyphae was minimal at the highest air-to-liquid ratio. In the cat-360 mutant strain, adhesion was observed at all ratios and increased considerably with aeration from many small aggregates to a single clump (Fig. 6A). Under these conditions, the final biomasses of all stains were similar (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

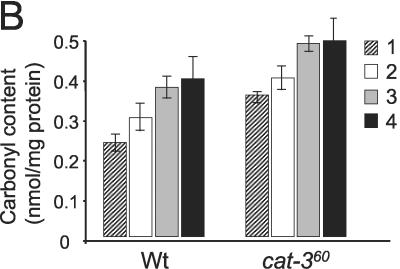

Adhesion of hyphae and carbonyl content of mycelia grown under different aeration conditions. Conidia from either Wt or cat-360 mutant cells were inoculated in liquid medium. Volumes of 20, 15, 10, or 5 ml were then poured into 25-ml Erlenmeyer flasks and incubated for 15 h at 30°C and 250 rpm. Cultures were transferred to petri dishes for documentation of hyphal adhesion, and thereafter, mycelium was recovered for determination of protein carbonyl content. Panels: A, adhesion of Wt and cat-360 mutant hyphae (lanes: 1, 5 ml [4:1 ratio]; 2, 10 ml [3:2 ratio]); B, protein carbonyl content from Wt or cat-360 mutant mycelium growing at an air-to-liquid ratio of 1:4 (columns 1), 2:3 (columns 2), 3:2 (columns 3), or 4:1 (columns 4). The results shown are averages of two independent experiments.

To confirm that hyphal adhesion observed was related to oxidative stress, protein oxidation was measured in total mycelial extracts. Protein oxidation, measured as carbonyl content in total protein, increased with hyphal adhesion and aeration in both strains but was consistently higher in the cat-360 mutant strain (Fig. 6B).

cat-3 mutants show increased development of aerial hyphae and formation of conidia.

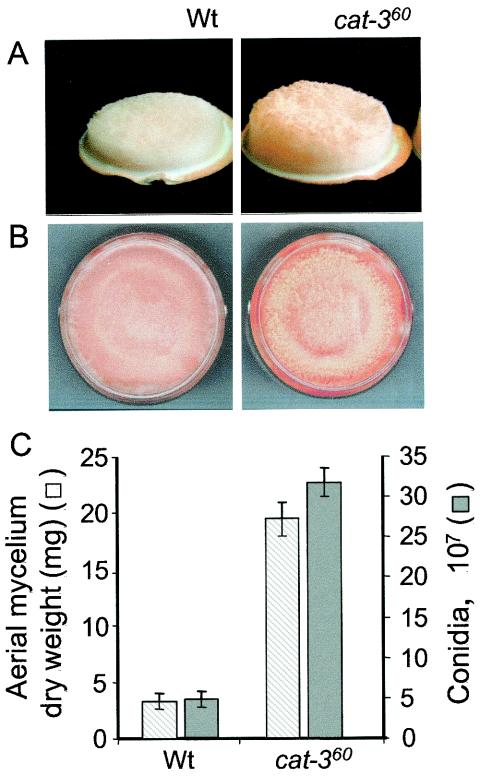

The second and third steps in the conidiation process are development of aerial hyphae and formation of conidia at the tips of aerial hyphae. The amount of aerial hyphae and conidia was determined in air-exposed mycelial mats. Aerial hyphae and conidia were more abundant in the cat-360 mutant strain than in the Wt (Fig. 7A and B). In fact, the mutant strain produced six times more aerial hyphae and conidia than did the Wt (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 7.

Enhancement of aerial hyphae and conidium formation in a cat-360 mutant strain. Wt and cat-360 mutant cultures (100 ml) were filtered, and the resulting mycelial mats were exposed to air for 24 h. Side (A) and top (B) views of the mycelial mats showing aerial mycelium (A) and conidia (B) from Wt and cat-360 mutant strains and aerial mycelium dry weight and numbers of conidia from Wt and cat-360 mutant strains (C) are depicted. The results shown in panel C are averages of four independent experiments.

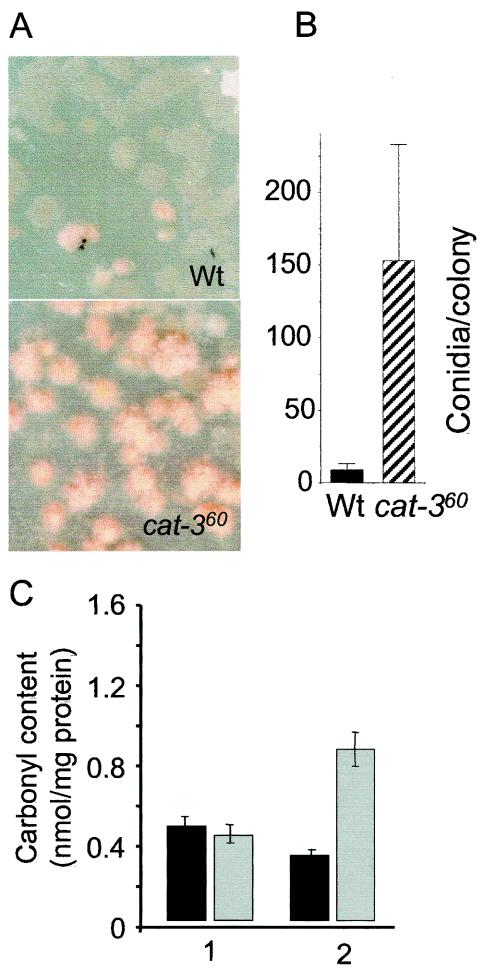

Aerial hyphae and conidia were also more abundant in 7-day-old colonies of the cat-360 mutant strain than in those of the Wt (Fig. 8A and B). To confirm that this trait was related to oxidative stress, protein oxidation was determined in colonies. After 3 days of growth in petri dishes, Wt and cat-360 mutant colonies had similar amounts of carbonyls in their total protein. Four days later, protein oxidation was lower in Wt colonies and twofold higher in cat-360 colonies (Fig. 8C), indicating oxidative stress in mutant colonies.

FIG. 8.

Conidiation of Wt and cat-360 mutant colonies. Colonies were grown on VSM for 7 days at 30°C. Panels: A, 7-day-old Wt and cat-360 colonies; B, number of conidia per colony (averages of three groups of 20 colonies picked at random are shown); C, protein carbonyl contents of Wt (dark bar) and cat-360 mutant (gray bar) colonies grown in the dark on cellophane-covered VSM plates after 3 (columns 1) or 7 (columns 2) days. The results shown are averages of four independent experiments.

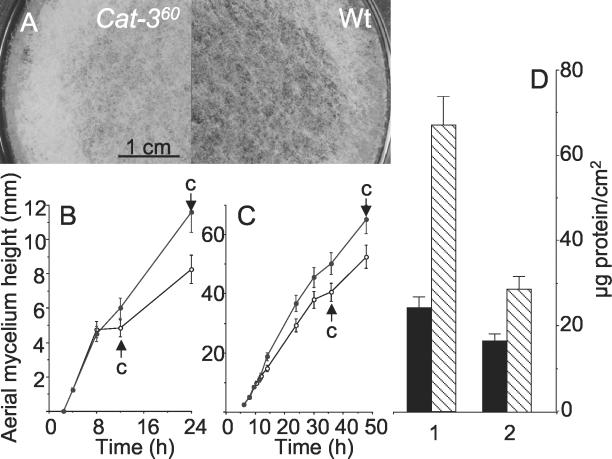

Counting of aerial hyphal initials per unit of area was not possible because aerial hyphae rapidly form a syncytium. To show an increase in aerial hyphae per unit of area, mycelial mats were covered with dark-purple-stained filter paper through which aerial hyphae can grow. In the cat-360 mutant, the whole paper was covered with aerial hyphae, while in the Wt, there was some uncovered space (Fig. 9A). Edges of the mycelial mat are more air exposed and develop more aerial hyphae, particularly in the cat-360 mutant strain (Fig. 9A). The height of aerial hyphae was measured by placing standing microscope slides on mycelial mats or holding them on the surface of liquid cultures. Aerial hyphae of the cat-360 mutant strain grew to a greater height than did those of the Wt and conidiated later in both systems (Fig. 9B and C). Compared to the Wt strain, the density of aerial hyphae that adhered to the slide was 2.75 times higher in the mutant in mycelial mats and 1.75 times higher in standing liquid cultures (Fig. 9D). The protein content per unit of dry weight of aerial hyphae was 198.5 ± 6.7 μg/mg in both strains. There was no indication of precocious development of aerial hyphae: aerial hyphae start to grow 2 h after air exposure of mycelial mats and 4 h in standing liquid cultures.

FIG. 9.

Aerial hyphal height in mycelial mats and in standing liquid cultures. (A) Mycelial mats were covered with darkly stained filter paper at the start of development. Aerial hyphae grew through the filter paper. Photographs taken after 24 h show increased density of aerial hyphae in the cat-360 mutant strain. Aerial mycelium heights in mycelial mats (B) and in standing liquid cultures (C) are also shown. Wt, open circles; cat-360, closed circles. The arrow labeled “c” indicates the time when conidiation was observed under a light microscope. (D) Amounts of aerial hyphae that stuck to 1-cm2 microscope slides placed on mycelial mats (columns 1) and on standing liquid cultures (columns 2). The results in panels B to D are averages of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Here we present evidence indicating that cat-3-null strains tend to develop oxidative stress (increased protein oxidation) and react by increasing antioxidant levels (carotenes) and developing large amounts of differentiated cell structures (adherent hyphae, aerial mycelium, and conidia). These results are in accordance with the O2 avoidance theory of cell differentiation (13, 15).

The lack of CAT-3 in mutant strains was not compensated for by other catalase activities, even under oxidative stress conditions, in contrast to what is observed in Xanthomonas campestris (44). In N. crassa, CAT-1 is expressed mainly in nongrowing cells (8, 30), CAT-4 is presumably restricted to peroxisomes, and CAT-2 is expressed in lysing hyphae (31a). Besides catalases, three peroxiredoxins, a glutathione peroxidase, cytochrome c peroxidase, and probably other peroxidases are found in the N. crassa genome (www.genome.wi.mit.edu). However, these enzymes are efficient only at low concentrations of H2O2; millimolar concentrations of H2O2 can only be disposed of by catalases (18, 32). Thus, despite such a high redundancy of H2O2-detoxifying enzymes, other enzymes cannot compensate for loss of CAT-3 activity because these enzymes are much less efficient, are expressed in other cells, or have a different intracellular localization. This may explain why the lack of CAT-3 had a great impact on the antioxidant capability and cell differentiation of N. crassa.

The susceptibility of cat-3RIP mutant strains was made evident by treatment of colonies with H2O2. Wt colonies were hardly affected by 20 mM H2O2, while cat-3RIP mutant strains did not survive this treatment. CAT-3 was shown to be secreted from Wt colonies and from hyphae in liquid cultures. The protein has a signal peptide for secretion that is processed (30). However, CAT-3 detected in the growth medium represents only a few percent (<3%) of the total catalase activity in cell extracts (data not shown). Thus, loss of CAT-3 into the medium is low and most of the activity in mycelial cell extracts is intracellular or bound to the cell wall.

Because lack of CAT-3 was not compensated for enzymatically, other antioxidants are expected to be induced in cat-3-null strains. Carotenes are antioxidants that are especially effective at quenching 1O2 (36). In N. crassa, carotenes are induced by light through the WC1/WC2 pathway but carotene induction during conidiation is independent of light and WC genes (16, 24). 1O2 is an inducer of carotene synthesis in Phaffia rhodozyma (33). 1O2 is produced by blue light through photosensitization reactions. However, in the dark, H2O2 is a main source for 1O2 generation (reviewed in reference 27). N. crassa carotene mutant strains are sensitive to light and 1O2 (37). 1O2 is generated during N. crassa conidial germination (26) and conidiation and under different stress conditions (heat shock or paraquat treatment) (30). Wt colonies hardly made carotenes when grown in the dark and synthesized them mainly when in the presence of light. Instead, cat-360 mutant colonies grown in the dark had increased carotene content. These results are consistent with 1O2 generation and 1O2 induction of carotene synthesis in mutant strains growing in the dark. Carotene synthesis in the Wt and cat-360 mutant strains was enhanced further by light and/or by 1O2 generated by photosensitization.

Besides carotene synthesis, cat-360 mutant hyphae tended to adhere to each other when grown in liquid cultures. Hyphal adhesion is related to a carbohydrate that is secreted and polymerized at the cell wall, functioning as cement between hyphae (W. Hansberg, unpublished observations). When a mycelial mat is exposed to air, a layer of adherent hyphae is formed within minutes. This layer of adherent hyphae is often mistakenly interpreted as desiccation. A layer of adherent hyphae also forms in standing liquid cultures and is not formed in mycelial mats in the absence of air or in the presence of antioxidants. Aerial hyphae develop only from the layer of adherent hyphae and represent the first step of the conidiation process (38). Only in this layer of the mycelial mat are proteins and specific enzymes oxidized and degraded and are some of them resynthesized (41). Hyphal adhesion correlated with protein oxidation in liquid cultures. cat-360 mutant hyphae grew as aggregates that increased in size depending on aeration; Wt hyphae also tend to form aggregate at a high aeration rate. Hyphal adhesion is a cellular response to oxidative stress. It probably has the effect of reducing the local concentration of O2 by active respiration. Deposited carbohydrates at the cell wall could also reduce the entrance of O2 into the adherent hyphae.

Aerial hyphae develop from adherent hyphae and conidia are formed at their tips, representing the second and third steps of the conidiation process. The most conspicuous features of cat-3-null strains are the increased amount of aerial hyphal mass and the number of conidia produced; both were six times the amount determined in the Wt strain. The increased amount of aerial hyphae was due to a combination of high density and a prolonged growth period, producing an aerial hyphal mass of increased height and density. The increased amount of aerial hyphae produced an increased amount of conidia. Conidiation was retarded in both the air-exposed mycelial mat and the standing liquid culture systems. The aerial hyphal morphology analyzed under a light microscope was similar in both strains.

Interestingly, the N. crassa Cu, Zn SOD-null mutant strain sod-1 (5) has a phenotype similar to that of the cat-3 mutant strain with respect to carotene production, adhesion of hyphae, and increased amount of aerial mycelium and conidium formation (Hansberg, unpublished). However, and as expected, the sod-1 mutant is more resistant to H2O2 and more sensitive to paraquat treatment than is the cat-3 mutant.

How oxidative stress triggers conidiation remains to be determined. During a hyperoxidant state, the amount and ratio of NAD(P)H/NAD(P) and glutathione/glutathione disulfide changes dramatically (40, 42) and this will change many metabolic fluxes. Besides, the redox state in cells is sensed through a cascade of protein kinases. Cytoplasmic catalase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is induced by the HOG1 pathway (34). Under these conditions, SOD is also regulated although through the protein kinase A-cyclic AMP (cAMP) and Skn7 pathways (11). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe (7) and Aspergillus nidulans (22), osmotic and oxidative stress activates the HOG1 homologues Spc1 and SakA, respectively. In N. crassa, the S. cerevisiae mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase Ste11 homologue NRC-1 and also a Tre/Ser protein kinase, NCR-2, have been found to be required for vegetative growth and to repress the onset of conidiation (23). The HOG1 homologue os-2 has been cloned, and its deletion has been shown to be osmosensitive and resistant to some fungicides, but there is no indication of an effect on conidiation (48). It would be interesting to find out if a catalase is regulated by one of these protein kinases in N. crassa.

Deletion of N. crassa gna-1, which encodes a Gαi protein, reduces the cAMP level, causing a decreased apical extension rate, carotene accumulation, increased tolerance to heat shock and H2O2 treatment, short aerial hyphae, and hyperconidiation, a phenotype similar to the adenylate cyclase-deficient cr-1 mutant strain. Mutant strains with Gαi permanently activated show an increased cAMP level, have an apical extension rate close to that of the Wt, a low carotene content, decreased tolerance to heat shock and H2O2 treatment, and increased proliferation of aerial hyphae but a low level of conidium formation (47).

cAMP levels are probably inversely related to stress intensity in N. crassa. In the cat-3 mutant, the stress is increased, and in the gna-1 mutant, the signal is increased. The stress and the signal both will induce antioxidant mechanisms (carotene synthesis). Thus, we expect low levels of cAMP in cat-3 mutant strains and induction of CAT-3 in gna-1 mutant strains.

During the conidiation process, oxidative stress is not continuous but is only generated at the start of each morphogenetic transition. Thus, in a cat-3RIP mutant strain, both aerial hyphal growth and conidiation are stimulated. In a gna-1 mutant strain, the signal is always on at its maximum (no cAMP) and the response is correspondingly maximal. Thus, the strain conidiates profusely, with no delay and without much growth of aerial hyphae.

Double and triple catalase mutant strains of A. nidulans had no apparent effect on conidiation, although colonies from catB mutant strains and conidia from catA mutant stains are sensitive to H2O2 (20, 21, 31). This could indicate different fungal strategies by which to cope with oxidative stress and to start cell differentiation. A. nidulans has been used mainly for genetic studies, and growth conditions and strains have been selected for rapid and abundant production of conidia. A. nidulans laboratory strains grow in pellets, which could be a protection mechanism against oxidative stress. Thus, we will test the phenotype of CatB-null strains, the CAT-3 homologue, under growth conditions similar to those used for N. crassa.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant IN214199 from DGAPA, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, and grant 33148-N from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, México.

We are grateful to Dan Ebbole (Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas) for help with the RIP protocol. We thank Jesús Aguirre (IFCE-UNAM) for critically reviewing the manuscript and Leonardo Peraza for the photographs in Fig. 9.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, B., S. G. Rhee, and E. R. Stadtman. 1987. Use of fluorescein hydrazide and fluorescein thiosemicarbazide reagents for the fluorometric determination of protein carbonyl groups and for the detection of oxidized protein on polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 161:245-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagyan, I., L. Casillas-Martinez, and P. Setlow. 1998. The katX gene, which codes for the catalase in spores of Bacillus subtilis, is a forespore-specific gene controlled by σF, and KatX is essential for hydrogen peroxide resistance of the germinating spore. J. Bacteriol. 180:2057-2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calera, J. A., S. Paris, M. Monod, A. J. Hamilton, J. P. Debeaupuis, M. Diaquin, R. López-Medrano, F. Leal, and J. P. Latge. 1997. Cloning and disruption of the antigenic catalase gene of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 65:4718-4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cambareri, E. B., B. C. Jensen, E. Schabtach, and E. U. Selker. 1989. Repeat-induced G-C to A-T mutations in Neurospora. Science 244:1571-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chary, P., D. Dillon, A. L. Schroeder, and D. O. Natvig. 1994. Superoxide dismutase (sod-1) null mutants of Neurospora crassa: oxidative stress sensitivity, spontaneous mutation rate and response to mutagens. Genetics 137:723-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis, R. H., and J. F. De Serres. 1970. Genetic and microbiological research techniques for Neurospora crassa. Methods Enzymol. 17A:79-143. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degols, G., K. Shiozaki, and P. Russell. 1996. Activation and regulation of the Spc1 stress-activated protein kinase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2870-2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Díaz, A., P. Rangel, Y. Montes de Oca, F. Lledías, and W. Hansberg. 2001. Molecular and kinetic study of catalase-1, a durable large catalase of Neurospora crassa. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 31:1323-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebbole, D. 1990. Vectors for construction of translational fusions of β-galactosidase. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 37:15-16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelmann, S., C. Linder, and M. Hecker. 1995. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of katE encoding a σB-dependent catalase in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:5598-5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a. Galagan, J. E., S. E. Calvo, K. A. Borkovich, et al. 2003. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature 422:859-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garay-Arroyo, A., F. Lledías, W. Hansberg, and A. A. Covarrubias. 2003. Nature 422: 859-868. The cytoplasmic Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for resistance to hyperosmosis. FEBS Lett. 539:68-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garre, V., U. Muller, and P. Tudzynski. 1998. Cloning, characterization, and targeted disruption of cpcat1, coding for an in planta secreted catalase of Claviceps purpurea. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:772-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansberg, W., and J. Aguirre. 1990. Hyperoxidant states cause microbial cell differentiation by cell insulation from dioxygen. J. Theor. Biol. 142:201-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansberg, W., H. de Groot, and H. Sies. 1993. Reactive oxygen species associated with cell differentiation in Neurospora crassa. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 14:287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansberg, W. 1996. A hyperoxidant state at the start of each developmental stage during Neurospora crassa conidiation. Cienc. Cult. 48:68-74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harding, R. W., and R. V. Turner. 1981. Photoregulation of carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in albino and white collar mutants of Neurospora crassa. Plant Physiol. 68:745-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hengge-Aronis, R. 1993. Survival of hunger and stress: the role of rpoS in early stationary phase gene regulation in E. coli. Cell 72:165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman, B., H. J. Hecht, and L. Flohe. 2002. Peroxiredoxins. Biol. Chem. 383:347-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson, C. H., M. G. Klotz, J. L. York, V. Kruft, and J. E. McEwen. 2002. Redundancy, phylogeny and differential expression of Histoplasma capsulatum catalases. Microbiology 148:1129-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki, L., D. Wysong, R. Diamond, and J. Aguirre. 1997. Two divergent catalase genes are differentially regulated during Aspergillus nidulans development and oxidative stress. J. Bacteriol. 179:3284-3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki, L., and J. Aguirre. 2001. Multiple catalase genes are differentially regulated in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 183:1434-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawasaki, L., O. Sánchez, K. Shiozaki, and J. Aguirre. 2002. SakA MAP kinase is involved in stress signal transduction, sexual development and spore viability in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1153-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kothe, G. O., and S. J. Free. 1998. The isolation and characterization of nrc-1 and nrc-2, two genes encoding protein kinases that control growth and development in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 149:117-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linden, H., and G. Macino. 1997. White collar 2, a partner in blue-light signal transduction controlling expression of light-regulated genes in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J. 16:98-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lledías, F., P. Rangel, and W. Hansberg. 1998. Oxidation of catalase by singlet oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 273:10630-10637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lledías, F., P. Rangel, and W. Hansberg. 1999. Singlet oxygen is part of a hyperoxidant state generated during spore germination. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 26:1396-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lledías, F., and W. Hansberg. 2000. Catalase modification as a marker for singlet oxygen. Methods Enzymol. 319:110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loewen, P. C., and J. Switala. 1988. Purification and characterization of spore-specific catalase-2 from Bacillus subtilis. Biochem. Cell Biol. 66:707-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolin, B. S., M. Freitag, and E. U. Selker. 1997. Improved plasmids for gene targeting at the his-3 locus of Neurospora crassa by electroporation. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 44:34-36. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michán, S., F. Lledías, J. D. Baldwin, D. O. Natvig, and W. Hansberg. 2002. Regulation and oxidation of two large monofunctional catalases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33:521-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navarro, R. E., M. A. Stringer, W. Hansberg, W. E. Timberlake, and J. Aguirre. 1996. catA, a new Aspergillus nidulans gene encoding a developmentally regulated catalase. Curr. Genet. 29:352-359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31a. Peraza, L., and W. Hansberg. 2002. Neurospora crassa catalases, singlet oxygen and cell differentiation. Biol. Chem. 383:569-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seaver, L. C., and J. A. Imlay. 2001. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:7173-7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schroeder, W. A., and E. A. Johnson. 1995. Singlet oxygen and peroxyl radicals regulate carotenoid biosynthesis in Phaffia rhodozyma. J. Biol. Chem. 31:18374-18379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schüller, C., J. L. Brewster, M. R. Alexander, M. C. Gustin, and H. Ruis. 1994. The HOG pathway controls osmotic regulation of transcription via the stress response element (STRE) of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CTT1 gene. EMBO J. 13:4382-4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Springer, M. L., and C. Yanofsky. 1989. A morphological and genetic analysis of conidiophore development in Neurospora crassa. Genes Dev. 3:559-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sundquist, A. R., K. Briviba, and H. Sies. 1994. Singlet oxygen quenching by carotenoids. Methods Enzymol. 234:384-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas, S. A., M. L. Sargent, and R. W. Tuveson. 1981. Inactivation of normal and mutant Neurospora crassa conidia by visible light and near-UV: role of 1O2, carotenoid composition and sensitizer location. Photochem. Photobiol. 33:349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toledo, I., J. Aguirre, and W. Hansberg. 1986. Aerial growth in Neurospora crassa: characterization of an experimental model system. Exp. Mycol. 10:114-125. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toledo, I., and W. Hansberg. 1990. Protein oxidation related to morphogenesis in Neurospora crassa. Exp. Mycol. 14:184-189. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toledo, I., A. A. Noronha-Dutra, and W. Hansberg. 1991. Loss of NAD(P)-reducing power and glutathione disulfide excretion at the start of induction of aerial growth in Neurospora crassa. J. Bacteriol. 173:3243-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toledo, I., J. Aguirre, and W. Hansberg. 1994. Enzyme inactivation related to a hyperoxidant state during conidiation of Neurospora crassa. Microbiology 140:2391-2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toledo, I., P. Rangel, and W. Hansberg. 1995. Redox imbalance at the start of each morphogenetic step of Neurospora crassa conidiation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 319:519-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vattanaviboon, P., and S. Mongkolsuk. 2000. Expression analysis and characterization of the mutant of a growth- and starvation-regulated monofunctional catalase gene from Xanthomonas campestris pv. Phaseoli. Gene 241:259-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vollmer, S. J., and C. Yanofsky. 1986. Efficient cloning of genes of Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:4869-4873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willekens, H., C. Langebartels, C. Tiré, M. van Montagu, D. Inzé, and van W. Camp. 1994. Differential expression of catalase genes in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia (L.). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10450-10454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, Q., and K. Borkovich. 1998. Mutational activation of Gαi causes uncontrolled proliferation of aerial hyphae and increased sensitivity to heat and oxidative stress in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 151:107-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, Y., R. Lamm, C. Pillonel, S. Lam, and J.-R. Xu. 2002. Osmoregulation and fungicide resistance: the Neurospora crassa os-2 gene encodes a HOG1 mitogen-activated protein kinase homologue. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:532-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]