Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

The purpose of this reported study was to determine healthcare utilization and costs associated with delayed diagnosis of bipolar disorder. With use of automated data from a large integrated health system in the Midwest, all patients with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder recorded in any inpatient or outpatient encounter from January 1, 2000 to August 31, 2002 were identified. The date of initial diagnosis was the index date. For each patient in the bipolar cohort, 5 comparison patients were randomly selected from the general population of health system members and matched with the bipolar patients by sex, race, and age (± 5 years). Data on healthcare utilization (inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, pharmacy) were collected with a focus on mental health, from January 1, 1990, through 1 year after the index date. The cohort is 62% female and 64% White. Median time between initial mental health diagnosis and bipolar diagnosis was 21 months, with 33% of subjects receiving a bipolar diagnosis within 6 months of their initial mental health diagnosis; however, for 31% of the remaining bipolar subjects, the time of their initial mental health presentation to bipolar diagnosis was 4 years or more. The number and duration of treatment with antidepressants increased as time to bipolar diagnosis increased. Patients with bipolar disorder had at least twice the number of interactions with the healthcare system before the index date than the non-bipolar comparison group. Mean monthly costs before and after bipolar diagnosis were not strikingly different for patients with bipolar disorder, but costs after bipolar diagnosis increased with increasing time to bipolar diagnosis. Bipolar disorder is a costly illness for which the impact on the healthcare system may vary depending on how quickly it is diagnosed. Delays in diagnosis appear related to additional costs after diagnosis.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder affects about 1% of the general population, with a 1-year community-based prevalence ranging from 1.2% in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study[1] to 1.3% in the National Comorbidity Survey.[2] Angst[3] reviewed 10 lifetime prevalence studies of bipolar I disorder from 1985 to 1994 and found a range of 0.0% to 0.7%; and for bipolar II, a prevalence of 0.2% to 3.0% in 9 studies conducted from 1978 to 1998. However, a ‘spectrum’ of the disorder is emerging, professed by Hirschfeld[4] and others, suggesting that subclinical symptoms may play a larger role and encompass a larger population than previously recognized or identified. Others[5] have shown that including the subclinical cases would increase the prevalence of bipolar disorder as much as 5-fold.

This article reports the results of a retrospective analysis of subjects diagnosed with bipolar disorder in an integrated health system. Specifically, the analysis examines and quantifies the time between first mental health-related encounter and bipolar diagnosis and the costs associated with delayed diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Readers are encouraged to respond to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Methods

Data Source

We conducted this study in a large, vertically integrated health system serving the primary and specialty healthcare needs of Midwestern residents. This system is affiliated with a multi-specialty, salaried, physician group that provides most of the care for health system patients. The health system also owns a large, nonprofit, mixed-model health maintenance organization (HMO). To optimize the computerized data available for this study, the population was limited to HMO members assigned to the medical group physicians.

Computerized Data Sources and Medical Records

The health system maintains an extensive, centralized system of computerized databases. Data for this study came from electronic and paper medical record review and 3 computerized databases: (1) the HMO membership file; (2) the outpatient pharmacy database; and (3) the encounter and claims databases.

The HMO membership database includes information about historical and current coverage dates, covered benefits, and the amount of copayments for which the enrollee is responsible. The pharmacy database contains information on outpatient prescriptions filled by members. To receive payment, HMO-contracted pharmacies, which include several major chains, must file a claim for each prescription filled. The HMO collects the claims information and stores the data in the HMO drug claims database. This database includes information on the date a member filled a prescription, drug name, national drug code, number of pills, dosage dispensed, and number of days supplied.

The encounter and claims databases store comprehensive patient data for outpatient, emergency department, and inpatient care delivered by the medical group. For each outpatient encounter, information about date of visit, diagnoses, physician delivering care, procedures delivered, and clinic in which the care was delivered are compiled. Likewise, for each inpatient stay, information is collected about admission and discharge dates, diagnoses, and procedures. In addition to these encounter-specific fields, data on the patient's age, sex, and race are available.

Study Population and Bipolar Cohort Definition

Using the data sources described, we identified all patients with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder from January 1, 2000, through August 31, 2002, by obtaining records of all patients who had an inpatient, outpatient, or emergency department encounter with an ICD-9 coded diagnosis indicative of bipolar disorder (296.00-296.06, 296.40-.46, 296.50-296.56, 296.60-296.66, 296.7, 296.80, 296.89). All coded diagnoses were reviewed in this process (ie, this identification was not limited to primary diagnoses). To distinguish newly diagnosed cases, we required that all patients be continuously enrolled in the health plan for at least 1 year before bipolar disorder diagnosis, and excluded from the study population all patients who had any previous encounter with the health system that was coded as bipolar disorder. The date of bipolar diagnosis was labeled the index date.

For each patient in the cohort, we downloaded all data on member enrollment (ie, dates that patient enrolled and disenrolled in the health plan), demographics (age, race, sex), and all available utilization (inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, and pharmacy encounters) for the period January 1, 1990, through August 31, 2003. Unless otherwise stated, the results presented here are limited to those patients with full pharmacy benefit and linkage.

For each patient in the cohort, we identified the first encounter with a mental health-related diagnosis that occurred from January 1, 1990, through the index date. The first mental health-related diagnosis was defined using the following ICD-9 codes: depression (296.2x, 296.3x, 311); anxiety (293.89 300.00, 300.01, 300.02, 300.20-300.23, 300.29, 300.3, 300.4, 300.9, 308.3, 308.4, 308.9, 309.81); substance abuse (303.00-305.90); schizoaffective disorder (2975.7x); and schizophrenia (295.xx, excluding 295.7x). An underlying assumption in our study is that among those who eventually received a bipolar diagnosis, previous mental health encounters may have represented early presentations of bipolar disorder that went unrecognized. We further assumed that when patients finally did receive a bipolar diagnosis, they did in fact have bipolar disorder.

The cohort of patients with bipolar disorder was then stratified according to the following categories: (1) patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder fewer than 6 months after first mental health-related visit; (2) patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder at least 6 months but less than 1 year after the first mental health-related visit; (3) patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder at least 1 year but less than 2 years after the first mental health-related visit; (4) patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder at least 2 years but less than 4 years after the first mental health-related visit; and (5) patients diagnosed with bipolar 4 years or more after the first mental health-related visit.

Identification and Follow-up of Comparison Cohort

For each patient in the bipolar cohort, we randomly selected 5 comparison patients from the general population of health system members and matched them with the patient with bipolar disorder by sex, race, and age (± 5 years). The index date for the matched patient with bipolar disorder (ie, the date of bipolar diagnosis) served as the index date for the comparison patients. As with members of the bipolar cohort, we required that comparison cohort patients be enrolled in the HMO for at least 1 year before the index date. Because patients with bipolar disorder were identified at the time of a visit (ie, the time the ICD-9 code was recorded), we required that the comparison patient have a visit within 60 days of the index date. This requirement most likely resulted in an analysis with the most conservative comparison of cost because, by definition, we selected a comparison population that may have higher healthcare utilization than the general population in the healthcare system.

Healthcare Utilization Data

For each patient in the cohort, we tabulated, using data as far back as 1990, all inpatient stays, outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and prescriptions filled beginning at the first mental health-related visit through the index date (ie, date of bipolar diagnosis). In addition, these same data were tallied for the 1-year period post-index date.

Cost Data

Data on costs are available beginning in 1995. Therefore, analyses of costs are limited to patients with a first mental health diagnosis recorded January 1, 1995 or later. For each patient in the study, we downloaded all encounters and prescriptions filled from the time of the first mental health-related visit through the index date. As with the health care utilization data, we also tallied costs incurred during the year following the index date. Encounters were categorized as follows: inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, pharmacy, and other.

Pharmacy data are stored such that actual costs paid are recorded in the database. The databases recording all other utilization that occurred from January 1, 1995 through December 31, 2000, store only charges. For utilization occurring during this time, we downloaded charges and applied corresponding cost-to-charge ratios stored in the databases to obtain costs. For January 1, 2001 through August 30, 2003, actual costs are recorded in the databases and were used for this analysis.

Data Analysis

We calculated the mean number of visits overall and per month of follow-up time (time between first mental health-related visit and index date) and the mean costs overall and per month of follow-up time, with corresponding standard deviations. T-tests were used to compare mean monthly costs before and after the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Differences in mean total costs 1 year after bipolar diagnosis were assessed by time from initial mental health encounter using ANOVA. Utilization data were categorized as follows: outpatient (primary care, specialty, mental health), laboratory tests, emergency department, inpatient stays, psychiatric inpatient stays, ambulatory short stay, and others. Cost data were categorized as follows: outpatient pharmacy, inpatient stays, outpatient visits, and emergency department encounters. Finally, to evaluate potential depression misdiagnoses, we tabulated all antidepressant prescriptions filled by the study population and calculated the total number of different antidepressants filled, the mean number of days exposed, and the proportion of follow-up time exposed overall and stratified by time between first mental health-related encounter and bipolar diagnosis.

Results

We identified 1084 patients with a bipolar disorder code recorded during the study period and 5420 comparison cohort patients. At their index visit, 82.4% of the bipolar disorder cohort was seen by the psychiatry department, 4.0% by primary care, and 1.8% in the emergency department. Most of the patients in this study had been enrolled in the health plan for a substantial time before bipolar diagnosis: 50% had been enrolled for 9 or more years, 24% for 5 to 9 years, 17% for 2 to 5 years, and 9.2% for 1 to 2 years.

The sociodemographics of the bipolar cohort with complete medical and pharmacy linkage are presented in Table 1. Notably, the cohort is 62% female, 75% are between 18 to 54 years of age, and 64% are White. Age is directly related to time between first mental health encounter and bipolar diagnosis, with 56% of patients younger than 17 years of age (vs 18% of those age 55 to 64) diagnosed within 6 months of initial mental health presentation. More than 50% of patients older than 35 years of age were diagnosed with bipolar disorder after at least 2 years with a previous mental health diagnosis. There were no striking differences in time to bipolar diagnosis by race or gender (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of Bipolar Cohort Overall and by Time to Index Date (N = 1084)

| Variable | Time Between First Mental Health-Related Encounter and Recorded Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OVERALL | < 6 mo | 6 mo to < 2 y | 2 to < 4 y | > 4 y | |

| Age Category 0-17 | 117 (10.8) | 66 (18.4) | 28 (13.2) | 13 (7.6) | 10 (2.9) |

| 18-34 | 288 (26.6) | 119 (33.2) | 66 (31.0) | 47 (27.5) | 56 (16.4) |

| 35-44 | 280 (25.8) | 86 (24.0) | 53 (24.9) | 42 (24.6) | 99 (29.0) |

| 45-54 | 249 (23.0) | 49 (13.7) | 45 (21.1) | 45 (26.3) | 110 (32.3) |

| 55-64 | 80 (7.4) | 14 (3.9) | 12 (5.6) | 15 (8.8) | 39 (11.4) |

| 65+ | 70 (6.5) | 25 (7.0) | 9 (4.2) | 9 (5.3) | 27 (7.9) |

| Sex Male | 411 (37.9) | 147 (41.0) | 70 (32.9) | 56 (32.8) | 138 (40.5) |

| Female | 673 (62.1) | 212 (59.1) | 143 (67.1) | 115 (67.3) | 203 (59.5) |

| Race African American | 337 (31.1) | 122 (34.0) | 67 (31.5) | 49 (28.7) | 99 (29.0) |

| White | 695 (64.1) | 210 (58.5) | 133 (62.4) | 117 (68.4) | 235 (68.9) |

| Other/unknown | 52 (4.8) | 27 (7.5) | 13 (6.1) | 5 (2.9) | 7 (2.1) |

| TOTAL | 1084 | 359 | 213 | 171 | 341 |

Among the cohort of patients with bipolar disorder, the median time between initial mental health diagnosis and diagnosis of bipolar disorder was 21 months (95% CI, 18-24 months) with 33% of subjects receiving a bipolar diagnosis within 6 months of their initial mental health diagnosis. Almost half (47%) of the remaining patients with bipolar disorder did not receive their diagnosis for at least 4 years from the time of their initial mental health presentation. The median time to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder differed by initial mental health diagnosis recorded in the encounter databases: a median of 1.3 years in patients first presenting with depression, 2.1 years among patients with anxiety, 2.8 years among patients with schizophrenia, and 1.6 years among those with substance abuse. Overall, 25% of subjects with a recorded mental health diagnosis were followed for more than 4 years before receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. One in 4 patients initially diagnosed with depression were followed for more than 3.3 years before receiving a bipolar diagnosis; similarly, 25% of the patients initially diagnosed with anxiety were followed for 4.9 years before bipolar diagnosis, as were 25% of those initially diagnosed with schizophrenia (4.8 years) and substance abuse (4.3 years).

Number of Antidepressants

Overall, 60% of the bipolar cohort had received at least 1 antidepressant prescription before diagnosis of bipolar disorder. By contrast, 13% of the matched comparison cohort filled an antidepressant prescription during the study period. The likelihood of filling a prescription for an antidepressant and the number of different antidepressants prescribed increased with increasing time between first mental health diagnosis and ICD-9 coded diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Table 2); 11.0% of all patients with bipolar disorder (vs 0.4% of comparison group) received 4 or more antidepressants before their bipolar diagnosis. When the lag time from initial mental health diagnosis to bipolar diagnosis was at least 4 years, almost 23% of patients with bipolar disorder received at least 4 different antidepressants, and took antidepressants during 21.1% of their pre-diagnosis time. Among patients in the comparison group, 1.0% of those followed for at least 4 years before the index date received at least 4 different antidepressants, spending 2.2% of pre-index date time on antidepressant medication.

Table 2.

Antidepressant Use Before Diagnosis, Stratified by Time Between First Mental Health Encounter and Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder (N = 1084)

| Variable | Time Between First Mental Health-Related Encounter and Bipolar Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N (%) | < 6 mosN (%) | 6 mos to < 2 yN (%) | 2 to < 4 yrsN (%) | > 4 yrsN (%) | |

| No. of antidepressants | |||||

| 0 | 432 (39.9) | 254 (70.8) | 59 (27.7) | 47 (27.5) | 72 (21.1) |

| 1 | 297 (27.4) | 89 (24.8) | 74 (34.7) | 56 (32.8) | 78 (22.9) |

| 2 | 161 (14.9) | 12 (3.3) | 47 (22.1) | 32 (18.7) | 70 (20.5) |

| 3 | 75 (6.9) | 4 (1.1) | 17 (8.0) | 11 (6.4) | 43 (12.6) |

| 4 | 44 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (6.1) | 9 (5.3) | 22 (6.5) |

| > 4 | 75 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.4) | 16 (9.4) | 56 (16.4) |

| Mean days exposed | 262.4 (± 522.6) | 11.7 (± 27.7) | 136.6 (± 150.6) | 259.7 (± 310.7) | 606.2 (± 782.2) |

| Proportion of follow-up time exposed | 22.5% (±30.1) | 17.1% (± 32.0) | 32.9% (± 32.9) | 23.9% (± 29.0) | 21.1% (± 24.6) |

| TOTAL | 1084 (100.0) | 359 (33.1) | 213 (19.7) | 171 (15.8) | 341 (31.5) |

The Costs and Utilization of Services

Overall, patients with bipolar disorder had twice the number of interactions with the healthcare system before the index date than the non-bipolar comparison group. More specifically, patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder had 3 times the number of non-mental health hospitalizations, 3 times the number of emergency department visits, and 14 times the number of outpatient mental health visits than did the comparison cohort before the index diagnosis. Mean utilization following bipolar diagnosis was 16.5 outpatient encounters, 1.2 emergency department visits, and 0.4 inpatient hospitalizations per year, and the pre-diagnosis trend continued during the year after the index date.

Individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder continued with twice the intensity of healthcare interactions overall, 4 times the number of non-mental health hospitalizations, 2.4 times the rate of emergency department visits, and 25.7 times the mean number of outpatient mental health encounters as the non-bipolar comparators. These ratios varied somewhat by time to bipolar diagnosis but did not appear to follow any particular pattern. During this post-bipolar diagnosis period, mean costs continued to be 2 to 3 times higher in patients with bipolar disorder compared with the comparison cohort patients.

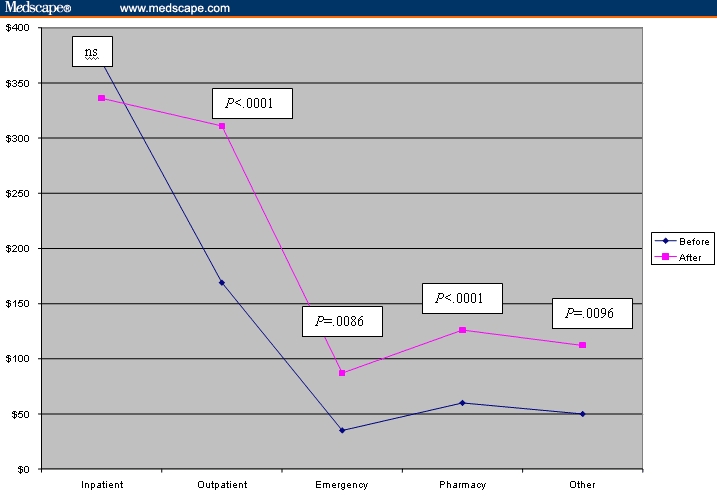

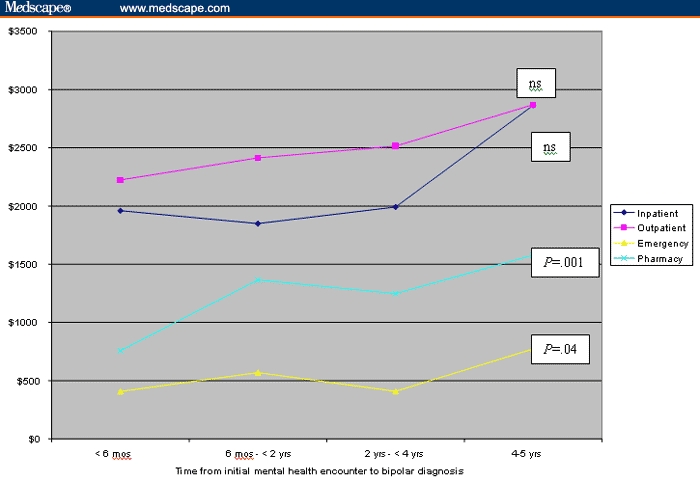

Mean monthly costs among the bipolar cohort were not strikingly different before and after bipolar diagnosis (Figure 1); however, several cost differences did reach statistical significance. The component costs of caring for the patient with bipolar disorder after diagnosis of bipolar disorder increased with the increase in time from initial mental health encounter to bipolar diagnosis; these results were statistically significant for emergency costs (P = .04) and pharmacy costs (P = .001) (Figure 2). The mean annual total costs for the patients with bipolar disorder in the year after diagnosis ranged from $6076 (among those with a 6-month lag to diagnosis) to $9496 (those with more than 4 years between the initial psychiatric diagnosis and bipolar diagnosis).

Figure 1.

Mean monthly cost per patient before and after bipolar diagnosis (n = 873).

Figure 2.

Mean total costs 1 year after bipolar diagnosis.

Discussion

This is the first study of bipolar disorder in a managed care setting that has attempted to address the broader issues of delays in recognition of the disorder and the potential costs associated with these delays. We found, as have others,[6–9] that bipolar disorder is costly and that those patients with bipolar disorder incur 2 to 4 times the health care costs as those without bipolar disorder. Although some numerical variation exists across studies, the differences are related to numerous factors including the definition of disease cohort and cost versus charges. For example, the work by Simon and Unützer[8] reflects actual costs whereas the remainder of the studies used charges, which are higher.[6,7,9] However, although inherent variations and limitations in these data sources make it difficult to precisely calculate the actual dollar value associated with bipolar disorder, relative comparisons conducted within each study are valid. Our study shows that differences in cost and utilization differ by time from initial mental health encounter to bipolar disorder diagnosis; however, we do not show substantive changes in mean monthly costs before and after the diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

The financial impact of bipolar disorder has been studied in a number of ways. The most cited study of the cost of bipolar disorder in the United States, conducted by Wyatt and colleagues,[6] indicates that 17% of the $45 billion in annual costs of bipolar disease are direct costs while the remaining costs are indirect costs. Other studies, using claims analyses, have shown that patients with bipolar depression incur 4 times the outpatient and twice the inpatient costs as those with bipolar mania.[7] Subsequent work by Simon and Unützer[8] at the staff-model Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound found that the average annual treatment costs for a patient with bipolar disorder was $3416, an amount exceeding that of depression ($2570), diabetes ($3083), and the general medical outpatient population ($1462). In addition, the costs were concentrated: 5% of patients with bipolar disorder accounted for 40% of the specialty mental health and substance abuse services. This estimate was eclipsed by that of Bryant-Comstock and colleagues,[9] who reported mean annual total costs of $7663.

Some investigators have explored the time to bipolar diagnosis based on previous mental health diagnoses or time in the healthcare system as a contributor to the overall costs of the disorder. In the 2000 survey of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (NDMDA),[10] more than one third of respondents with bipolar disorder were found to have sought professional help within 1 year of the onset of symptoms; however, 69% were misdiagnosed, most frequently with unipolar depression. Patients who were misdiagnosed consulted a mean of 4 physicians before receiving the correct diagnosis and one third waited 10 years or more before receiving an accurate diagnosis. Despite having underreported manic symptoms, more than 50% of patients believe that their physicians' poor understanding of bipolar disorder prevented a correct diagnosis from being made earlier.[10]

The literature contains evidence that bipolar disorder is an underdiagnosed condition. In a recent clinical series from 1 center, 37% to 40% of patients with a hospital discharge diagnosis of bipolar disorder had been considered to have unipolar depression prior to admission.[11,12] These findings are extremely pertinent to the current effort, because prescribing activating antidepressants, such as some of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, may actually exaggerate the mania symptoms associated with bipolar disorder and lead to adverse outcomes, including switching and rapid cycling.[13–16] Retrospective analysis by Perugi and colleagues[17] has shown that rapid cycling (in addition to suicide and psychotic symptoms) is more likely to manifest in those whose bipolar illness includes depression at onset than in those with manic or mixed state onset. This finding has led to uncovering a link between antidepressant medication use and the induction of rapid cycling because of the higher rates of antidepressant use in those with depressive onset.

These potential delays in diagnosis result in indirect costs as well as actual costs to the healthcare system. Birnbaum and colleagues,[18] in their analysis of a cohort of patients on antidepressants, found that patients with unrecognized bipolar disorder incurred significantly higher mean monthly medical costs in the 12 months following initiation of antidepressant treatment when compared with patients with recognized bipolar disorder ($1179 vs $801) and nonbipolar patients taking antidepressants ($585). Monthly indirect costs from these employer data were also higher in the patients with unrecognized bipolar disorder ($570 vs $514 in recognized patients with bipolar disorder and $335 in patients without bipolar disorder on antidepressants).

Our study examined treatment patterns of antidepressants and utilization before and after the index bipolar diagnosis, and several issues emerged. First, using our definition and assumptions, our results show that although one third of patients with bipolar disorder were identified within 6 months of their initial mental health encounter, another third (31%) went for at least 4 years from their initial mental health encounter until the initial bipolar diagnosis (Table 1). This finding was of interest because it suggested that, in some cases, either some clinicians were better than others in recognizing and referring patients or that some cases were far more difficult to diagnose. In either case, assuming that bipolar disorder was present at the initial presentation with depressive symptoms, the data indicate that barriers still exist in our ability to identify bipolar disorder in the general patient population setting and to distinguish it from unipolar depression. This latter point was confirmed by the number of antidepressants and the time that patients remain on antidepressants. Our data show that as time between the initial mental health encounter and bipolar disorder diagnosis increases, so do the number and proportion of patients who receive multiple trials of different antidepressants.

The possibility of unrecognized bipolar disorder being treated as depression is also suggested by Birnbaum and colleagues,[18] who found a significant proportion of patients with unrecognized bipolar disorder among their cohort of 9009 patients treated for depression. In addition, Russell and colleagues[19] found that 51% of patients with a bipolar diagnosis were initially diagnosed with depression. Russell's work further shows the economic impact, which accumulates with each additional antidepressant medication regimen change. Subsequent analyses will examine the extent to which these patients are treated in primary care as having depression, are treated as such, and, after treatment fails, are referred to a psychiatry specialist, who finally makes the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Of note, 82.4% of the patients with bipolar disorder in this study were seen in the psychiatry department at their index visit.

Our analysis also examined the cost implications of the time lapse before patients were diagnosed with bipolar disorder and found that these delays may result in excess costs both during the time of the delay and after diagnosis. This finding seems to be consistent with analyses from other cohorts[18,19] reporting that additional costs accrue in those patients with undetected bipolar disorder. This finding may reflect treatment refractoriness in the post-bipolar diagnosis period or more intensive treatment, and also suggests that more aggressive recognition and treatment can reduce healthcare costs.

Study Limitations

There are several potential limitations to the use and interpretation of these data. First, this analysis is based on claims and encounter data, relying on coded diagnoses and encounters. Using claims-based data to measure disease may reflect misdiagnosis, bias, and underdiagnosis. In this analysis we assumed that the diagnosis of bipolar disorder is correct and that, for the purposes of this analysis, the patient may have been able to be detected earlier in their course of disease given their previous mental health diagnoses. We feel comfortable with a coded diagnosis of bipolar disorder, however, because Unützer and colleagues[20] found in their medical record review validation of bipolar disorder cases that the false-positive rate was less than 10% for an outpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder. More than 74% of those in our bipolar cohort had a second bipolar coded encounter within 1 year of their initial bipolar diagnosis. It is possible that some patients with bipolar disorder could receive healthcare services outside of the health system studied; given that these patients are enrolled in a prepaid plan, however, there is a strong disincentive to obtain such services outside the health plan. Most of the patients with bipolar disorder in this study had been enrolled in the health plan for a substantial time before their bipolar diagnosis; 44.6% of them had been enrolled for 10 or more years.

These data represent the payer viewpoint and, in many ways, characterize a population based on economic impact from a payer perspective. One must interpret financial information carefully. We did not attempt to attribute individual visits as related or not related to underlying mental health illness and, thus, we can make no direct statements about what costs are directly attributable to bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we required the comparison cohort patients to have made at least 1 visit within 60 days of the index date because patients with bipolar disorder were defined by a coded visit. As mentioned previously, this requirement most likely resulted in an analysis with the most conservative comparison of cost because, by definition, we selected a comparison population that may have higher healthcare utilization than the general population in the healthcare system. Therefore, any gaps in healthcare utilization identified in this study are probably underestimates of the actual differences. Last, although high utilization rates were observed among patients with bipolar disorder, we found that costs did not differ before and after bipolar disorder diagnosis. This finding suggests that, in some cases, the index diagnosis may not have been a new diagnosis.

Conclusions

Bipolar disorder is a costly illness for which the impact on the healthcare system may vary depending on how quickly it is diagnosed. Delays in diagnosis may affect total healthcare costs but delay also appears to be related to additional costs after diagnosis. This is the first study to look at the impact of delays in diagnosis during an extended time and quantify these costs over time. Further research with more complete case ascertainment should be undertaken to further clarify the impact of speed of diagnosis and impact of disease.

Funding Information

This research was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Contributor Information

Paul E. Stang, College of Health Sciences, West Chester University, College of Health Sciences, West Chester, Pennsylvania; Galt Associates, Blue Bell, Pennsylvania; Email: pstang@drugsafety.com.

Cathy Frank, Outpatient Services, Department of Psychiatry, Henry Ford Health Systems, Detroit, Michigan.

Anupama Kalsekar, Lilly, Indianapolis, Indiana; GlaxoSmithKline.

Marianne Ulcickas Yood, Galt Associates, Blue Bell, Pennsylvania; Epidemiology and Public Health, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut; Josephine Ford Cancer Center, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan.

Karen Wells, Josephine Ford Cancer Center, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan.

Steven Burch, Global Health Outcomes, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina.

References

- 1.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1 year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angst J. The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirschfeld RM. Bipolar spectrum disorder: improving its recognition and diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: a re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affective Disord. 2003;73:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyatt RJ, Henter I. An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness: 1991. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30:213–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00789056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu AZ, Krishnan AA, Harris SD, et al. The economic burden of bipolar-related phases of depression versus mania. Drug Benefit Trends. 2004;16:569–575. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon GE, Unützer J. Health care utilization and costs among patients treated for bipolar disorder in an insured population. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1303–1308. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.10.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant-Comstock L, Stender M, Devercelli G. Health care utilization and costs among privately insured patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:398–405. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschfeld RMA, Lewis L, Vornick LA. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the national depressive and manic-depressive association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:161–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affective Disord. 1999;52:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:804–808. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D, Laddomada P, et al. Course of the manic depressive cycle and changes caused by treatments. Pharmakopsychiatrie Neuro-Psychopharmakologie. 1980;13:156–167. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1019628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altshuler LL, Post RM, Leverich GS, et al. Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1130–1138. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic Depressive Illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wehr TA, Goodwin FK. Can antidepressants cause mania and worsen the course of affective illness? Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1403–1411. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.11.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perugi C, Micheli C, Akiskal HS, et al. Polarity of the first episode, clinical characteristics, and course of manic-depressive illness: a systematic retrospective investigation of 320 bipolar I patients. Comp Psychiatry. 2000;41:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(00)90125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Dial E, et al. Economic consequences of not recognizing bipolar disorder patients: a cross-sectional descriptive analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1201–1209. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell J, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. The cost consequences of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:341–347. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unützer J, Simon GE, Pabiniak C, et al. The use of administrative data to assess quality of care for bipolar disorder in a large staff model HMO. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]