Abstract

Primary ovarian pregnancy is a rare form of ectopic pregnancy that must be demonstrated with use of 4 Spiegelberg criteria. It is usually diagnosed at laparotomy or laparoscopy, although it may resemble a hemorrhagic corpus luteum. Successful conservative management of ovarian pregnancy with methotrexate has been reported only occasionally. This may be partly because of the rarity of this condition and partly because when medical treatment is successful, the patient does not need to undergo laparotomy or laparoscopy, and an occasional ovarian pregnancy may have been diagnosed as a tubal pregnancy. We present a case of ovarian pregnancy (diagnosed at laparotomy) for which initial medical management with methotrexate failed despite favorable prognostic factors. Whether the unusual location (ovary) could have contributed toward treatment failure is unknown.

Readers are encouraged to respond to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Introduction

Medical management with methotrexate is an accepted and successful modality for treating early ectopic pregnancy. It is not always successful, however, and some factors are known to be associated with failure of medical management. The site of ectopic pregnancy has not reported to be associated with failure of medical management. Yet, we report a case of ovarian pregnancy (diagnosed at laparotomy) for which management with methotrexate failed despite favorable prognostic factors.

Primary ovarian pregnancy is a rare form of ectopic pregnancy that must be demonstrated with use of the 4 criteria of Spiegelberg, which are[1]: The fallopian tube, including the fimbria ovarica, is intact and clearly separate from the ovary; the gestational sac definitely occupies the normal position of the ovary; the sac is connected to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament; and the ovarian tissue is unquestionably demonstrated in the wall of the sac. The incidence of primary ovarian pregnancy is reported to be 1 in 7000 deliveries and accounts for 1% to 3% of all ectopic pregnancies.[2] In contrast to patients with tubal pregnancies, traditional risk factors such as pelvic inflammatory disease and prior pelvic surgery may not play a significant role in the etiology; ovarian pregnancy is more frequent in ectopic pregnancies associated with the use of contraceptive intrauterine devices.[3] A case of an intrafollicular ovarian pregnancy after ovulation induction/intrauterine insemination in a woman with primary infertility of 4 years has also reported; however, that patient also had endometriosis and adhesions on laparoscopy.[4]

Primary ovarian pregnancy is usually diagnosed only at laparotomy/laparoscopy, although it may resemble a hemorrhagic corpus luteum. For example, a correct diagnosis at the time of surgery could be made in only 28% in a series of 25 cases, because it was difficult to distinguish an ovarian pregnancy from a hemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst intraoperatively.[5] Recently, a case was diagnosed with 3-dimensional sonography.[6]

Conservative management is the initial approach in patients desirous of child-bearing. Successful conservative management with methotrexate (used systemically or locally) has been reported in 4 cases of documented ovarian pregnancy.[7–10]

Case Report

A 30-year-old woman with primary infertility of 12 years presented at 6 weeks plus 6 days amenorrhea with a positive pregnancy test and lower abdominal pain but no vaginal bleeding. Her previous menstrual cycles had been regular. She had undergone ovulation induction but not intrauterine insemination some years earlier and was currently not taking any treatment for infertility.

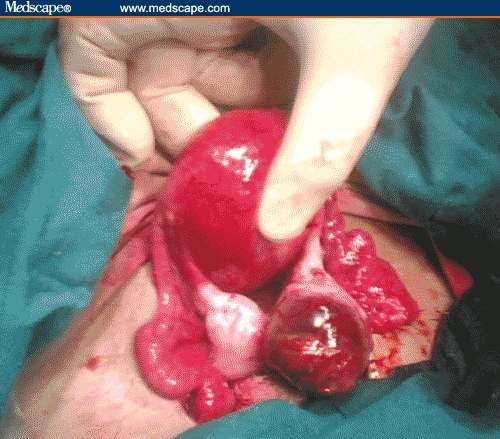

She was hemodynamically stable and her hemoglobin was 12.0 g/dL. On bimanual examination, the uterus was of normal size, and there was an approximate 4-cm tender right adnexal mass. Serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-HCG) was 400 mIU/mL. Ultrasound revealed an empty uterus with an endometrial thickness of 11.2 mm and a 2.8 × 1.6 cm right adnexal mass that contained a well-defined gestational sac of 0.8 cm. There was no fetal node or cardiac activity or free fluid. A diagnosis of unruptured ectopic pregnancy was made, and the patient received a single injection of methotrexate intramuscularly the next day (70 mg, ie, 50 mg/m2). She showed no clinical and laboratory signs of toxicity. The serum beta-HCG measurement could not be repeated on day 4, as per standard protocol, and was performed on day 7 (amenorrhea 8 weeks). The result, available a day later, indicated beta-HCG was 1225 mIU/mL. Repeat ultrasound showed the same findings. In view of rising beta-HCG, a second dose of methotrexate was administered (the patient now at 8 weeks and 2 days amenorrhea). After the second dose, beta-HCG values on day 4 and day 7 were 1400 mIU/mL and 2023 mIU/mL, respectively. Ultrasound on day 7 again showed an empty uterine cavity with a right adnexal mass 3 × 2.6 cm containing a 0.8-cm gestational sac. There was no cardiac activity or fetal node or free fluid. Laparotomy was performed in view of rising titers of beta-HCG. The uterus, both fallopian tubes (including the fimbria ovarica), and left ovary were normal. There were no adhesions or endometriosis. The right ovary was enlarged 5 × 5 cm with a congested bulge of 3 × 3 cm on one side that had yellowish-red corpus luteum on one side (Figure 1). This was thought to be an ovarian pregnancy. It was excised completely by wedge resection and the ovary was reconstructed. The patient's postoperative period was uneventful. Histopathologic studies confirmed an ovarian pregnancy. The excised portion of the ovary demonstrated first-trimester chorionic villi, decidua, endometrial stromal tissue fragments, and fragments of ovarian stromal tissue.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative view of right ovarian pregnancy. Notice the yellowish-red corpus luteum on the left side of the congested ovarian pregnancy.

Discussion

In the past, ovarian pregnancy had been treated by ipsilateral oophorectomy, but the trend has since shifted toward conservative surgery such as cystectomy or wedge resection performed at either laparotomy or laparoscopy. Currently, laparoscopic surgery is the treatment of choice.

This case is interesting because of the rarity of ovarian pregnancy and failure of medical management despite the fact that prerequisites predicting successful outcome with medical management were fulfilled. Medical management is offered in early unruptured ectopic pregnancies having serum beta-HCG < 5000-10,000 mIU/mL, no fetal cardiac activity, and adnexal mass < 3.5-4 cm. The success rate of single-dose methotrexate is 87% with 8% of patients needing a second dose.[11,12]

Some factors predicting failure of medical management with methotrexate are high serum beta-HCG level, high serum progesterone level, presence of cardiac activity,[12] presence of yolk sac,[13] high pretreatment folic acid levels,[14] lack of side effects of methotrexate,[15] and endometrial thickness > 12 mm.[16] In a study of 350 women with tubal ectopic pregnancies who were treated with methotrexate intramuscularly according to a single-dose protocol, a logistic regression analysis of the some of the factors predicting methotrexate success (or failure) demonstrated that the pre-treatment serum beta-HCG level was the only factor that contributed significantly to the failure rate, whereas the size and volume of the mass, the volume of hematoma, and the presence or absence of free blood in the pelvis were not associated with a significant risk of treatment failure.[12] One possible explanation for the lack of correlation of failure with size of the gestational mass is that the ectopic mass could not be distinguished from a surrounding blood clot with use of transvaginal ultrasonography. In addition, size does not always predict the relative health and blood supply of the ectopic mass. The prognostic value of other proposed factors (progesterone level and fetal cardiac activity) appeared to be directly related to their association with the serum beta-HCG concentration. According to this review, the use of methotrexate in women with pre-treatment serum beta-HCG level < 1000 IU/L was associated with a success rate of 98% (95% confidence interval [CI], 96-100), and a level between 1000 and 1999 IU/L was associated with a success rate of 93% (95% CI, 85-100). Furthermore, a level between 2000 and 4999 IU/L was associated with a success rate of 92% (95% CI, 86-97), a level between 5000 and 9999 IU/L was associated with a success rate of 87% (95% CI, 79-98), a level between 10,000 and 14,999 IU/L was associated with a success rate of 82% (95% CI, 65-98), and a level equal to or above 15,000 IU/L was associated with a success rate of 68% (95% CI, 49-88).[12]

This patient had nearly all features that predict successful medical management; ie, low beta-HCG level, endometrial thickness < 12 mm, no cardiac activity, and no yolk sac. Her pretreatment beta-HCG level was only 400 IU/L, a factor shown to be associated with best success rate with methotrexate (98%).[12] Her progesterone levels were not measured. Although her serum folic acid levels were also not estimated, she was not taking peri-conceptional folic acid supplementation. However, she did not exhibit any side effects to methotrexate, which has also been shown to predict treatment failure.

Kudo and colleagues[7] first reported successful use of methotrexate to treat an ovarian pregnancy. Shamma and Schwartz[8] successfully treated an ovarian pregnancy diagnosed laparoscopically by a single intramuscular injection of methotrexate (50 mg/m2). The pre-treatment beta-HCG level was about 5000 mIU/mL. Chelmow and colleagues[9] reported successful resolution of an ovarian pregnancy with intramuscular methotrexate. This ovarian pregnancy was diagnosed only after histologic examination of a biopsy specimen obtained from a suspected ruptured corpus luteal cyst wall at the time of laparoscopy. Mittal and colleagues[10] successfully treated an ovarian pregnancy with 50-mg methotrexate injected into the ectopic sac at laparoscopy. The pre-treatment beta-HCG level was 3000 mIU/mL.

Although methotrexate is an effective therapeutic option for the management of unruptured ectopic pregnancy, this case demonstrates that it may fail despite the presence of factors predicting successful outcome. It is not clear whether methotrexate failure is more likely in the case of ovarian ectopic pregnancy than tubal ectopic pregnancies; neither is it known whether similar criteria should be applied to the conservative management of ovarian ectopic pregnancies as to the management of tubal ectopic pregnancies. Because initial diagnosis in ovarian pregnancy is difficult, many of these cases will be diagnosed as possible tubal pregnancies only.

Site may or may not have been a reason for failure, but this was the only prominent odd feature in this case where all criteria for a successful medical management had been fulfilled. A well-defined gestational sac in the adnexa was identified by 3 observers in the presence of a low beta-HCG level of only 400 IU/L. The ovary and the tube get their blood supply from similar sources (branches of uterine and ovarian vessels); thus, inadequate circulation leading to methotrexate failure appears an unlikely explanation. However, an ovarian pregnancy is usually located peripherally toward the peritoneal cavity, and this location may have a reduced blood flow. Therefore, the amount of methotrexate delivered to it would be lower. A reduced blood supply may possibly also explain the low beta-HCG level, ie, less beta-HCG may enter the systemic circulation. Chelmow and colleagues[9] also reported low pre-methotrexate beta-HCG levels of 29 and 30 mIU/mL. Doppler blood flow assessment may be appropriate for analysis in future cases.

Future reporting of cases with methotrexate failure may give clearer answers as well as identify different criteria that might be necessary for the conservative care of ovarian ectopic pregnancies.

References

- 1.Spiegelberg O. Zur Casuistik den Ovarial-Schwangenschaft. Arch Gynaekol. 1878;13:73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimes HG, Nosal RA, Gallagher JC. Ovarian pregnancy: a series of 24 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:174–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ercal T, Cinar O, Mumcu A, Lacin S, Ozer E. Ovarian pregnancy; relationship to an intrauterine device. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;37:362–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1997.tb02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bontis J, Grimbizis G, Tarlatzis BC, Miliaras D, Bili H. Intrafollicular ovarian pregnancy after ovulation induction/intrauterine insemination: pathophysiological aspects and diagnostic problems. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:376–378. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallatt JG. Primary ovarian pregnancy: a report of twenty-five cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;143:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90683-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghi T, Banfi A, Marconi R, et al. Three-dimensional sonographic diagnosis of ovarian pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:102–104. doi: 10.1002/uog.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudo M, Tanaka T, Fujimoto S. A successful treatment of left ovarian pregnancy with methotrexate. Nippon-Sanka-Fujinka-Gakkai-Zasshi. 1988;40:811–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shamma FN, Schwartz LB. Primary ovarian pregnancy successfully treated with methotrexate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1307–1308. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chelmow D, Gates E, Penzias AS. Laparoscopic diagnosis and methotrexate treatment of an ovarian pregnancy: a case report. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:879–881. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittal S, Dadhwal V, Baurasi P. Successful medical management of ovarian pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;80:309–310. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pisarska MD, Carson SA, Buster JE. Ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1998;351:1115–1120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11476-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipscomb GH, McCord ML, Stovall TG, Huff G, Portera SG, Ling FW. Predictors of success with methotrexate treatment in women with tubal ectopic pregnancies. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1974–1978. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912233412604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potter MB, Lepine LA, Jamieson DJ. Predictors of success with methotrexate treatment of tubal ectopic pregnancy at Grady Memorial Hospital. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1192–1194. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takacs P, Rodriguez L. High folic acid levels and failure of single-dose methotrexate treatment in ectopic pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2005;89:301–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnhart KT, Gosman G, Ashby R, Sammel M. The medical management of ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis comparing “single dose” and “multi dose” regimens. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:778–784. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)03158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takacs P, Chakhtoura N, De Santis T, Verma U. Evaluation of the relationship between endometrial thickness and failure of single-dose methotrexate in ectopic pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;272:269–272. doi: 10.1007/s00404-005-0009-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]