Abstract

Tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV) and other tombusviruses encode a p19 protein (P19), which is a suppressor of RNAi. Wild-type TBSV or p19-defective mutants initially show a similar infection course in Nicotiana benthamiana, but the absence of an active P19 results in viral RNA degradation followed by recovery from infection. P19 homodimers sequester 21-nt virus-derived duplex siRNAs, and it is thought that this prevents the programming of an antiviral RNA-induced silencing complex to avoid viral RNA degradation. Here we report on chromatographic fractionation (gel filtration, ion exchange, and hydroxyapatite) of extracts from healthy or infected Nicotiana benthamiana plants in combination with in vitro assays for ribonuclease activity and detection of TBSV-derived siRNAs. Only extracts of plants infected with p19 mutants provided a source of sequence-nonspecific but ssRNA-targeted in vitro ribonuclease activity that coeluted with components of a wide molecular weight range. In addition, we isolated a discrete ≈500-kDa protein complex that contained ≈21-nt TBSV-derived siRNAs and that exhibited ribonuclease activity that was TBSV sequence-preferential, ssRNA-specific, divalent cation-dependent, and insensitive to a ribonuclease inhibitor. We believe that this study provides biochemical evidence for a virus–host system that infection in the absence of a fully active RNAi suppressor induces ssRNA-specific ribonuclease activity, including that conferred by a RNA-induced silencing complex, which is likely the cause for the recovery of plants from infection.

Keywords: suppression, silencing, RNA-induced silencing complex

In response to virus infection, plants can activate virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), which is an antiviral RNAi pathway capable of specifically recognizing and degrading viral RNA (1–3). Many viruses have evolved VIGS suppressors to block the RNAi-mediated host defense, apparently as an adaptive viral response to this protective surveillance system. The particular mode of action of different virus-encoded suppressors may vary (4, 5), but their general purpose appears to be preventing VIGS-mediated degradation of viral genomic RNA (gRNA) or mRNA transcripts (2, 6, 7). One of the best characterized suppressors is the Tombusvirus-encoded p19 protein (P19); it interferes with RNA silencing in plants and RNAi in other model systems (2, 3, 8). In the context of Tombusvirus infections, P19 prevents RNAi-mediated viral RNA degradation, which correlates with a dramatic exacerbation of the disease phenotype compared with infections with virus mutants not expressing P19 (9–16).

Tombusvirus replication in plants involves the accumulation of abundant levels of highly structured single-stranded and double-stranded virus RNAs (17, 18). These molecules are thought to form substrates for one of the initial steps in RNAi whereby the RNase III-like enzyme Dicer cleaves dsRNA (and/or highly structured ssRNAs) into duplex siRNAs (19–22). Tombusvirus siRNAs in infected plants represent regions scattered along the entire viral RNA genome (17).

P19 forms soluble homodimers that preferentially bind dsRNA through sequence-nonspecific electrostatic interactions between residues in the protein groove of the dimer and the sugar–phosphate backbone of the RNA duplex (23, 24). Caliper tryptophan residues on either side of the P19 dimers are positioned such that the complex preferentially binds 21-bp siRNAs (23, 24). Thus, P19-mediated suppression of VIGS presumably occurs through the appropriation of ≈21-nt Tombusvirus-derived duplex siRNAs. In turn, this property is thought to prevent incorporation of these siRNAs into an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (3). This model is supported by observations that the ability of P19 to sequester Tombusvirus-derived siRNAs during infection correlates with a compromised viral RNA degradation (2, 25).

Genetic studies also have provided support for the aforementioned model for antiviral RNA silencing and its suppression by virus proteins, especially for plant–virus systems (2, 8, 26–28). However, direct biochemical evidence for, and characterization of, antiviral RNAi effector complexes, such as RISC, remain to be reported for any virus–host system. The present study uses Tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV), the type member of the tombusviruses, and its experimental host Nicotiana benthamiana, to test whether antiviral ribonucleases are induced upon infection. For this purpose, plant extracts were subjected to three independent chromatography separation techniques in combination with in vitro assays for ribonuclease activity and siRNA detection.

Extracts obtained from healthy plants or from those infected with TBSV expressing wild-type (wt)P19 did not reveal the presence of high-molecular weight (MW) TBSV–siRNA-containing complexes with the capacity to degrade TBSV RNA in vitro. However, initial gel filtration with extracts from plants infected with TBSV not expressing P19 yielded a multitude of collected fractions with sequence-nonspecific ribonuclease activity in vitro. When gel-filtration assays were performed on plants infected with a TBSV P19 mutant (P19/R43W) that has an intermediate pathogenicity phenotype, compared with wtP19 and that observed in absence of P19 (9), the virus-nonspecific influence of some high-MW nucleases was significantly lower. Gel-filtration, ion-exchange, and hydroxyapatite column chromatography also yielded a discrete high-MW (≈500 kDa) ribonucleoprotein complex that contained TBSV-specific siRNAs and exhibited divalent cation-dependent, TBSV RNA-preferential ribonuclease activity in vitro. These in vitro findings correlate with the observation that, in the absence of an active P19, plants recover from infection with TBSV.

Results and Discussion

Plants Infected with TBSV P19-Suppressor Mutants Contain ssRNA-Specific Ribonucleases.

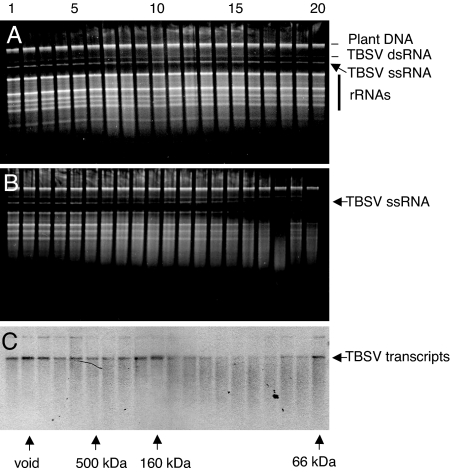

First, the hypothesis was tested that, in response to viral infection, plants can trigger the induction of ribonuclease activity that targets virus RNA. For this purpose, gel-filtration chromatography fractionation was performed with extracts from healthy and TBSV-infected plants, through a Sephacryl S-200 HR column. The eluted fractions were analyzed for the presence of in vitro cleavage activity against total RNA obtained from TBSV-infected plants, which includes rRNAs and TBSV ssRNA and dsRNA (Fig. 1). Results of such in vitro cleavage experiments with gel-filtration fractions obtained from healthy or mock-inoculated plants did not reveal the presence of high-MW (>100 kDa) complexes with ribonuclease activity (Fig. 1A). This result is in agreement with the assertion that noninoculated plants should not contain preprogrammed RISC-like complexes directed against virus RNA (1, 2).

Fig. 1.

In vitro RNA cleavage assays with gel-filtration fractions collected from healthy or wt TBSV-infected plants. (A and B) Healthy (A) or TBSV-infected (B) N. benthamiana extracts were subjected to gel-filtration chromatography on a Sephacryl S-200 HR column, and collected fractions were tested for the ability to cleave total RNA extracted from TBSV-infected N. benthamiana plants, as visualized by ethidium bromide staining of nucleic acids. (C) Fractions shown in B were tested for in vitro cleavage of TBSV transcripts visualized by Northern blot hybridization. Select numbers on the top indicate the order of collected fractions (1–20). Arrows and abbreviations to the right indicate the positions of plant chromosomal DNA (plant DNA), viral dsRNA (TBSV dsRNA) or viral ssRNA (TBSV ssRNA), and plant rRNAs. Arrows on the bottom indicate the fractions representing the void volume and the extrapolated elution profile of standard MW markers on the same column.

Similar in vitro cleavage experiments with extracts from N. benthamiana plants infected with TBSV expressing wtP19 showed that low-MW fractions contained sequence-nonspecific ribonucleases that degraded TBSV RNA as well as rRNAs (Fig. 1B). However, high-MW fractions (>100 kDa) did not display ribonuclease activity toward TBSV RNA isolated from infected plants (Fig. 1B) or TBSV transcripts in vitro (Fig. 1C). Previously, it was shown that, in plants infected with wt Tombusvirus, viral-derived siRNAs exclusively associated with P19 (12, 14, 29). These findings, along with those reported here, agree with the model that, during infection, wtP19 dimers sequester Dicer-generated ≈21-nt TBSV duplex siRNAs to avoid their programming of a high-MW antiviral RISC-like complex and thus prevent the onset of RNAi-mediated viral RNA degradation (2).

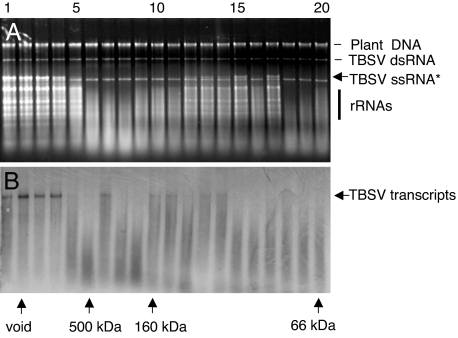

The progression of infection and symptom development on N. benthamiana plants inoculated with a TBSV p19-mutant devoid of P19 expression (TBSV-dP19) is initially very similar to that observed for wt TBSV (9, 14, 15). However, instead of eventually succumbing to a lethal necrosis, plants infected with tombusviruses devoid of P19 expression develop a recovery phenotype associated with viral RNA clearance (2). To test the premise that these manifestations correlated with the induction of one or more virus-specific ribonucleases in the absence of P19, gel-fractionation and in vitro RNA cleavage tests were conducted with extracts from plants infected with TBSV-dP19. Ribonuclease activity tests showed that, in addition to the aforementioned low-MW nucleases, fractions containing high-MW complexes (160 to >500 kDa) showed ribonuclease activity directed toward TBSV ssRNA (Fig. 2). Plant rRNAs were also targeted, whereas plant chromosomal DNA or TBSV dsRNA were not affected (Fig. 2A). The high-MW fractions exhibiting the ssRNA-specific nuclease activity also cleaved in vitro generated TBSV transcripts in presence of RNase A inhibitor (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

In vitro RNA cleavage assays with fractions of plants infected with a TBSV mutant that does not express P19. (A) Gel-filtration chromatography fractions were collected from N. benthamiana infected with TBSV-dP19, as for Fig. 1, and tested for cleavage of total RNA extracted from wt TBSV-infected N. benthamiana plants. (B) The same fractions were tested for cleavage of TBSV transcripts that were synthesized and tested in the presence of RNase A inhibitor. The asterisk indicates a pair of closely spaced bands, the upper band corresponding to TBSV genomic ssRNA and the lower band corresponding to TBSV dsRNA of subgenomic RNA2 (18), which resisted degradation. Visualization and labeling is as for Fig. 1.

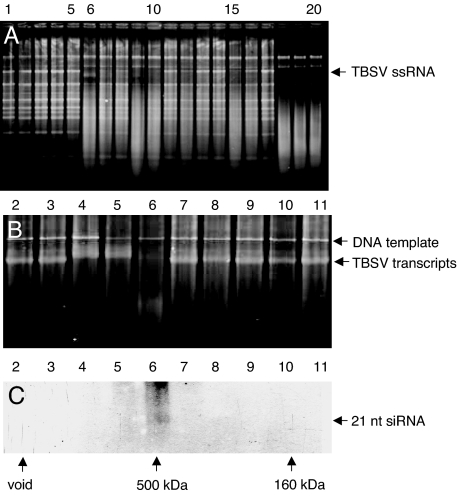

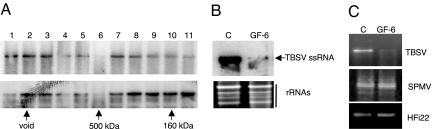

Notwithstanding our considerable interest in virus-induced sequence-nonspecific nuclease activity in a number of fractions, our primary intention was to test the hypothesis that P19 prevents TBSV-mediated activation of a discrete siRNA-containing high-MW (possibly RISC-like) antiviral effector complex. The results obtained thus far indicate that fractions from plants infected with TBSV-dP19 contained one or more complexes of ≈200–500 kDa. To provide independent evidence, gel-filtration and ribonuclease activity experiments were conducted with the TBSV mutant expressing P19/R43W. In comparison with wtP19, P19/R43W does not bind siRNAs as efficiently (14). As observed for TBSV-dP19 (Fig. 2), the results obtained with TBSV-P19/R43W (Fig. 3) again showed the presence of low-MW, ssRNA-targeting, sequence-nonspecific ribonucleases that cleaved both TBSV ssRNA and plant rRNA (Fig. 3A). However, one particular gel-filtration fraction (GF), GF-6 (Fig. 3A), representing eluted high-MW components (≈500 kDa) preferentially cleaved TBSV RNA in purified total RNA from plants (although rRNAs were still affected) (Fig. 3A). GF-6 also effectively cleaved in vitro synthesized TBSV transcripts (Fig. 3B). Compared with the high-MW ribonuclease activity for dP19 that was spread out over GF-5 to GF-9 (Fig. 2), the activity associated with P19/R43W was predominantly present in GF-6, representing ≈500 kDa complexes (Fig. 3). Thus, the results with dP19 and P19/R43W independently indicate that, in absence of a fully active wtP19, high-MW ribonuclease complexes are activated in TBSV-infected plants.

Fig. 3.

In vitro RNA cleavage assays and siRNA detection in fractions from plants infected with a TBSV mutant expressing P19/R43W. (A and B) GFs were tested (as Fig. 1) for cleavage of total RNA extracted from TBSV-infected N. benthamiana plants (A) or in vitro generated TBSV transcripts (the higher band represents the DNA template) (B). Symbols, numbers, and abbreviations are as for Fig. 1. (C) Fractions obtained after gel filtration were concentrated and subjected to urea-gel denaturing electrophoresis followed by Northern blot hybridization by using a TBSV-specific probe. The arrow on the right indicates the position of TBSV ≈21-nt siRNAs.

Previous gel-filtration experiments with extracts from wt TBSV-infected plants showed that 21-bp TBSV-derived siRNAs were not detectable in high-MW (≈500 kDa) fractions, presumably because of the sequestration of all siRNAs by wtP19 resulting in ≈60 kDa P19/siRNA complexes (14). However, gel-fractionated extracts of plants infected with TBSV-P19/R43W revealed the presence of ≈21-nt TBSV siRNAs in GF-6 (Fig. 3C) that also exhibited ssRNA-specific ribonuclease activity (Fig. 3B). This provided supportive evidence for our previous deduction (14) that the failure of P19/R43W to bind all available TBSV siRNAs resulted in the “leaky transfer” of a siRNA subset to a high-MW nuclease effector complex.

Briefly, the results obtained thus far show the presence of ribonuclease activity in plants infected with TBSV P19 mutants compromised for suppression, and some of the activity is associated with one or more high-MW (≈500 kDa) complexes. The absence of ribonucleases in healthy plants clearly indicated that the detected activity is induced by virus infection. Moreover, the induction of nuclease activity is profoundly suppressed by the expression of wtP19 by TBSV in planta.

TBSV-Preferential Ribonuclease Is Associated with a Discrete High-MW Complex That Contains Viral siRNAs and Requires Divalent Cations for in Vitro Activity.

Rather than being functionally associated with the same complex, it is possible that the ribonuclease activity and siRNAs simply coelute from the gel-filtration column. Additionally, it was deemed desirable to reduce the effects attributable to the sequence-nonspecific ribonucleases. For these reasons, DEAE ion-exchange chromatography was used with extracts from N. benthamiana plants infected with TBSV-d19 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

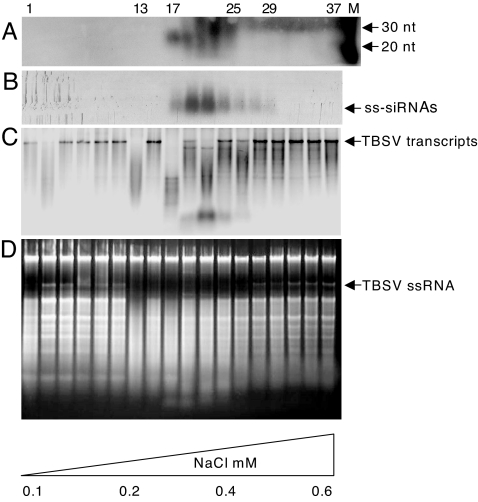

Activity tests and siRNA detection for ion-exchange fractions obtained from N. benthamiana plants infected with TBSV-dP19. (A) Denaturing gel-electrophoresis followed by Northern blot hybridization for the detection of ≈21-nt TBSV-specific siRNAs in fractions collected on DEAE ion-exchange chromatography (every other fraction was tested). The positions of RNA size markers are indicated on the rightmost side of the blot. (B) Native agarose gel electrophoresis followed by Northern blot hybridization to detect TBSV-specific siRNAs. (C and D) Fractions were tested for in vitro cleavage of TBSV transcripts followed by Northern blot hybridization (C) or total RNA extracted from TBSV-infected N. benthamiana plants as visualized by ethidium bromide staining after treatments (D). Numbers on the top indicate the individually collected fractions (1–37). Arrows on the right indicate positions of TBSV RNA (for this particular experiment, the dsRNA is not visible on the gel). Numbers on the bottom indicate the increasing NaCl concentration.

First, the distribution of total eluted TBSV siRNAs was monitored by subjecting the collected ion-exchange chromatography fractions to urea-gel denaturing electrophoresis followed by Northern blot hybridization with a TBSV-specific probe. As shown in Fig. 4A, fractions containing ≈21-nt TBSV siRNAs eluted at concentrations of 250–400 mM NaCl. Again, in accordance with the anti-TBSV RNAi model (2), such siRNAs coeluted with wtP19 upon ion exchange fractionation of extracts from plants infected with wt TBSV (data not shown), most likely because wtP19 had sequestered these molecules (14). The denaturing conditions used in Fig. 4A presumably resulted in detection of total siRNAs (i.e., ssRNA plus dsRNA), whereas ribonuclease complexes like RISC are assumed to contain ssRNAs. Therefore, samples of the collected fractions were also subjected to native agarose gel RNA separation followed by Northern blot hybridization (Fig. 4B). Although these tests do not conclusively demonstrate that exclusively ssRNAs are present, they do support an argument against the notion that there are only short dsRNAs in the active fractions.

To determine whether the siRNA-containing ion-exchange chromatography fractions exhibited ribonuclease activity, they were mixed with TBSV transcripts (Fig. 4C) or with total RNA from infected plants (Fig. 4D). Although ion-exchange eluted fraction 13 (IF-13) degraded TBSV RNA (Fig. 4C), this sample did not contain detectable amounts of TBSV siRNAs (Fig. 4 A and B) and may represent one or more nonspecific nucleases. However, the siRNA-containing fractions IF-17 through IF-27 targeted TBSV transcripts albeit with different efficiencies (Fig. 4C), and all of these degraded TBSV RNA in total RNA extracts (Fig. 4D). Some level of nonspecific in vitro nuclease activity toward rRNA was also observed (Fig. 4D).

It was important to ascertain whether the high-MW siRNA-containing ribonuclease complex isolated with ion-exchange chromatography (Fig. 4) and the complex isolated with Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration (Figs. 2 and 3) were the same. For this purpose, the fractions eluted from the ion-exchange column that contained ≈21-nt TBSV siRNAs and exhibiting ribonuclease activity were concentrated and subjected to gel fractionation. In vitro ribonuclease tests on those eluted GFs again showed that GF-6, representing high-MW complexes of ≈500 kDa, contained TBSV-specific siRNAs (data not shown) and degraded in vitro generated TBSV transcripts (Fig. 5A Upper) as well as viral RNA from plants (Fig. 5A Lower). These data confirm that the ssRNA-specific virus-induced ribonuclease obtained with ion-exchange and gel-filtration chromatography is most likely the same and represents a discrete high-MW complex. Importantly, the combination of two chromatography fractionation procedures resulted in increased specificity of the complex because the ribonuclease effectively targeted TBSV RNA, whereas rRNAs remained mostly unaffected (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, control transcripts representing mRNA of a Nicotiana tabacum transcription factor (HFi22) (30) or of satellite panicum mosaic virus (31) were not targeted (Fig. 5C), verifying the specificity of the activity associated with GF-6.

Fig. 5.

TBSV-specific ribonuclease activity upon ion-exchange chromatography followed by gel filtration. Fractions containing ≈21-nt TBSV siRNAs after DEAE ion-exchange chromatography with extracts from N. benthamiana plants infected with TBSV-dP19 were concentrated and fractionated on a Sephacryl S-200 HR column. (A) Aliquots of eluted fractions were tested for RNA cleavage with TBSV in vitro synthesized transcripts (Upper) or with TBSV gRNA extracted from infected plants (Lower), detected by Northern blot hybridization with a TBSV-specific probe. (B) Aliquots of GF-6 (5 μl) were incubated with total RNA extracted from TBSV-infected plants. Also shown is the control (C) incubation of RNA with elution buffer. TBSV gRNA was detected by Northern blot hybridization with a TBSV-specific probe (Upper), and the ethidium bromide stained gel (Lower) shows the plant rRNAs in the same samples. (C) Agarose gel electrophoreses of transcripts from TBSV, satellite panicum mosaic virus (SPMV), or HFi22 (representing a host mRNA), after incubation with GF-6 or an inactive control (C) fraction. Visualization is by ethidium bromide staining.

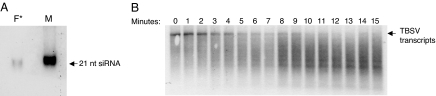

A third isolation procedure using hydroxyapatite chromatography followed by ion-exchange chromatography again showed association of TBSV siRNAs (Fig. 6A) with fractions that effectively targeted TBSV RNA (Fig. 6B). Time course experiments showed that ≈0.5 μg of TBSV RNA was cleaved within 5 min on addition of 5 μl of the ribonuclease fraction, indicating that the isolated effector complex is quite effective under the in vitro conditions (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Isolation of an siRNA-containing ribonuclease complex by using a hydroxyapatite column followed by ion-exchange chromatography. (A) Hydroxyapetite fractions with ribonuclease activity were combined and subjected to ion-exchange chromatography. The active fractions were again pooled and subjected to RNA isolation followed by gel electrophoresis and Northern blot hybridization with a TBSV-specific probe (F*). The right lane was loaded with a ≈21 TBSV siRNA as a positive marker (M). (B) A time course (minutes) RNA cleavage test with the siRNA-containing ribonuclease fraction from A (F*) mixed with in vitro generated TBSV transcripts, detected by Northern blot hybridization. The reactions were stopped by the addition of buffer (100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/20 mM sodium EDTA). The arrow on the right indicates the position of full-length TBSV transcripts; degradation products, some of seemingly distinct sizes, migrate underneath.

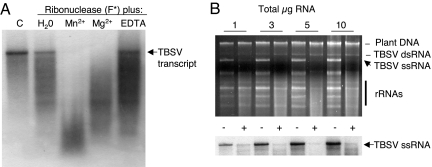

The next experiments aimed to determine whether the activity of the high-MW siRNA-associated ribonuclease depends on divalent cations in vitro, as reported for RISC with other systems (32–34). The results showed that the ribonuclease activity was inhibited by addition of EDTA to the reaction mix, whereas addition of Mg2+ or Mn2+ had a profound stimulatory effect (Fig. 7A). Addition of Mg2+ or Mn2+ partially rescued the EDTA-blocked activity of the ribonuclease, whereas increasing concentrations of the divalent metal chelator (exceeding 20 mM) completely prohibited the cleavage reaction (data not shown). This indicates that the inhibitory effect of EDTA on the ribonuclease activity is a direct result of metal chelation. Finally, it was found that reduction of the amount of total RNA substrate in the reaction diminished the nonspecific degradation of rRNAs although not impacting the effective degradation of viral RNA (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Effects of divalent metal cations and substrate concentration on the high-MW ribonuclease activity. (A) A fraction similarly prepared as described for Fig. 6 was tested for ribonuclease activity toward TBSV transcripts in the presence of water, 2 mM MnCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, or 10 mM EDTA. A control (C) treatment lacked nuclease addition to transcripts. The treatments are indicated at the top of each lane, and the RNA is detected by Northern blot hybridization. The arrow on the right indicates the position of TBSV RNA transcripts. (B) Ribonuclease activity was tested with increased concentrations of total RNA extracted from TBSV-infected plants (indicated on top). (Upper) Visualization by ethidium bromide staining of the gel before transfer for the Northern blot hybridization shows the chromosomal DNA, TBSV dsRNA and ssRNA, and rRNAs, as indicated on the right. (Lower) The effect of ribonuclease addition on the integrity of TBSV gRNA as detected by Northern blot hybridization with a TBSV-specific probe. −, water was added as a control; +, addition of the siRNA-containing ribonuclease fraction.

The attributes described here for the ≈500 kDa anti-TBSV effector complex are consistent with RISC-like nuclease properties (34–37). The catalytic unit of the antiviral nuclease is probably an ≈100-kDa Argonaut-family protein (34, 38–B40), but it cannot be completely ruled out that the complex described here has a different nuclease core. Irrespective of the identity of the catalytic entity, under the conditions used in this study, the nuclease must be complexed with other components to assemble into an ≈500-kDa unit. This is consistent with predictions by others (as reviewed in ref. 41) that the holoRISC is a multiunit complex. In this context it is also noteworthy that native agarose gel-electrophoresis experiments showed that longer (>100 nt) TBSV ss- and dsRNAs are associated with the high-MW fractions displaying ribonuclease activity (data not shown), indicating that these may be components of the in vivo assembled antiviral holocomplex.

Conclusions

Extracts from N. benthamiana plants infected with TBSV in absence of a fully functional P19 suppressor contain ssRNA-targeting ribonuclease activity that coeluted with complexes of a wide MW range from ≈50 to >600 kDa. Under the in vitro conditions used in this study such ribonuclease activity was mostly sequence-nonspecific. However, three independent separation techniques readily yielded a virus-induced, discrete, ≈500-kDa complex containing TBSV RNA-derived siRNAs that exhibited ribonuclease activity that was TBSV RNA-preferential, ssRNA-specific, and divalent cation-dependent. We propose to refer to this complex as a virus-activated RISC-like complex (VARC).

Further studies should be conducted to determine whether VARC represents a bona fide Argonaute-containing RISC or an effector complex with thus far unreported attributes. Nevertheless, the induction of VARC and the other virus-activated ribonuclease complexes is linked to RNA silencing-associated TBSV RNA degradation and the recovery of plants infected with TBSV p19-defective mutants.

Materials and Methods

Inoculation and Analyses of Plants.

In vitro generated transcripts of full-length cDNAs expressing wtP19 (pTBSV-100), dP19 (pHS157), and P19/R43W were prepared essentially as described (42), and details about the constructs have been provided (9, 14, 15). The plasmids (1 μg) were linearized at the 3′ terminus of the viral cDNA sequence by digestion with SmaI. Transcript RNAs synthesized by using T7 RNA polymerase were used for inoculation of N. benthamiana plants as described (18).

RNA Analyses.

Total RNA was extracted by grinding ≈200 mg of leaf material (inoculated or systemically infected leaves) on ice in 1 ml of extraction buffer (100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0/1 mM ETDA/0.1 M NaCl/1% SDS). Samples were extracted twice with 1:1 (vol/vol) phenol/chloroform at room temperature and precipitated with an 8 M 1:1 (vol/vol) lithium chloride solution at 4°C for 1 h. The resulting pellets were washed with 70% ethanol and then resuspended in RNase-free distilled water and used for Northern blot hybridization. Approximately 10 μg of total plant RNA was separated in 1% agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes (Osmonics, Westborough, MA). TBSV (gRNA and subgenomic RNAs) were detected by hybridization with [32P]dCTP-labeled TBSV-specific probes, essentially as described (18).

Sephacryl S-200 Fractionation.

Infected N. benthamiana leaf tissue (3 g) was homogenized in 3 ml of extraction buffer (200 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/5 mM DTT/150 mM NaCl), filtered through cheesecloth, and centrifuged twice for 15 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant (1 ml) was loaded and fractionated on a column (2.5 × 80 cm) packed with Sephacryl S-200 high-resolution resin (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) at a flow rate of 1.3 ml/min. The column was equilibrated with elution buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/100 mM NaCl) and calibrated with gel filtration MW standards (12–200 kDa) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Ion-Exchange Chromatography.

Infected N. benthamiana leaf tissue (25 g) was homogenized in 50 ml of loading buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4/5 mM DTT). The extract was filtered through cheesecloth and centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant (50 ml) was loaded onto a 15 × 2.5 cm column packed with MacroPrep DEAE Support (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The column was washed with 200 ml of loading buffer, and the bound proteins were subsequently eluted with a gradient of increasing concentrations of NaCl (0.1–0.9 M). Every other fraction (2 ml) was analyzed for the presence of RNA cleavage activity and siRNAs.

Hydroxyapatite Column Chromatography.

Infected N. benthamiana leaf tissue (50 g) was homogenized in 50 ml of loading buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.8). The extract was filtered through cheesecloth and then centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant (100 ml) was loaded onto a 12 × 3.5 cm column packed with Hydroxyapatite Bio-Gel HT (Bio-Rad). The column was washed with 300 ml of loading buffer, and the bound proteins were subsequently eluted with a gradient of increasing concentrations (10–200 mM) of sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). Every other fraction (3 ml) was analyzed for the presence of RNA cleavage activity and siRNAs.

Detection of TBSV siRNAs.

To dissociate siRNAs from protein complexes, 300-μl aliquots of each fraction collected on the chromatography procedures were treated with 10% SDS (30 μl) at 65°C for 15 min, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction. RNA was then precipitated with 2.5 volumes of 100% ethanol, resuspended, and separated in 17% acrylamide gels in the presence of 8 M urea, followed by electroblotting onto nylon membranes (Osmonics). Alternatively, siRNAs were electrophoresed through native agarose gels followed by capillary transfer. TBSV-specific siRNAs were detected by hybridization with [32P]dCTP-labeled TBSV-specific probes at 47°C followed by autoradiography. As a nucleotide size marker, the Decade Marker System (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used in experiments.

Target RNA Cleavage Assays.

RNA cleavage assays were performed with TBSV transcripts or total RNAs extracted from wt TBSV-infected N. benthamiana plants (i.e., RNAs that had not been targeted by RNAi in vivo). Typically, cleavage reactions were carried out for 60 min at 24°C in presence of 15 units/ml RNase A inhibitor (Ambion). The reactions were stopped by the addition of buffer containing (100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/20 mM sodium-EDTA). RNAs were separated by electrophoresis through 1% agarose gels, visualized by staining with ethidium bromide, and transferred to nylon membranes (Osmonics). TBSV RNA was detected by hybridization with [32P]dCTP-labeled TBSV-specific probes, essentially as described (18).

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen-Beth G. Scholthof for helpful discussions and for editing the manuscript; Yi-Cheng Hsieh, Dong Qi, and Kristina Twigg for various valuable contributions during the experiments. This work was supported by Texas Agricultural Experiment Station Grant TEX08387, National Institutes of Health Grants 1R03-AI067384-01, U.S. Department of Agriculture Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service/National Research Initiative/Challenge Grants Program Grant 2006-35319-17211, and National Science Foundation Grant MCB0131552 (to H.B.S.). J.J.C. is a recipient of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Willy May Harris Charitable Trust Graduate Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- GF

gel-filtration fraction

- gRNA

genomic RNA

- MW

molecular weight

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- TBSV

tomato bushy stunt virus

- wt

wild-type.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

References

- 1.Baulcombe D. Nature. 2004;431:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature02874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scholthof HB. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:405–411. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silhavy D, Burgyan J. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qu F, Morris TJ. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5958–5964. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth BM, Pruss GJ, Vance VB. Virus Res. 2004;102:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakatos L, Csorba T, Pantaleo V, Chapman EJ, Carrington JC, Liu YP, Dolja VV, Calvino LF, Lopez-Moya JJ, Burgyan J. EMBO J. 2006;25:2768–2780. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merai Z, Kerenyi Z, Kertesz S, Magna M, Lakatos L, Silhavy D. J Virol. 2006;80:5747–5756. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01963-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamore PD. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R198–R200. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu M, Desvoyes B, Turina M, Noad R, Scholthof HB. Virology. 2000;266:79–87. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turina M, Omarov R, Murphy JF, Bazaldua-Hernandez C, Desvoyes B, Scholthof HB. Mol Plant Pathol. 2003;4:67–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu F, Morris TJ. Mol Plant–Microbe Interact. 2002;15:193–202. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silhavy D, Molnar A, Lucioli A, Szittya G, Hornyik C, Tavazza M, Burgyan J. EMBO J. 2002;21:3070–3080. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Havelda Z, Hornyik C, Valoczi A, Burgyan J. J Virol. 2005;79:450–457. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.450-457.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omarov R, Sparks K, Smith L, Zindovic J, Scholthof HB. J Virol. 2006;80:3000–3008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.3000-3008.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholthof HB, Scholthof K-BG, Jackson AO. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1157–1172. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu W, Park JW, Scholthof HB. Mol Plant–Microbe Interact. 2002;15:269–280. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molnar A, Csorba T, Lakatos L, Varallyay E, Lacomme C, Burgyan J. J Virol. 2005;79:7812–7818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7812-7818.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholthof HB, Morris TJ, Jackson AO. Mol Plant–Microbe Interact. 1993;6:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamore PD, Tuschl T, Sharp PA, Bartel DP. Cell. 2000;101:25–33. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nykanen A, Haley B, Zamore PD. Cell. 2001;107:309–321. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vargason JM, Szittya G, Burgyan J, Tanaka Hall TM. Cell. 2003;115:799–811. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00984-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye K, Malinina L, Patel DJ. Nature. 2003;426:874–878. doi: 10.1038/nature02213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamura Y, Scholthof HB. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:491–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baulcombe DC, Molnar A. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:279–281. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deleris A, Gallego-Bartolome J, Bao J, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC, Voinnet O. Science. 2006;313:68–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1128214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voinnet O. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakatos L, Szittya G, Silhavy D, Burgyan J. EMBO J. 2004;23:876–884. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desvoyes B, Faure-Rabasse S, Chen MH, Park JW, Scholthof HB. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1521–1532. doi: 10.1104/pp.004754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scholthof K-BG. Mol Plant–Microbe Interact. 1999;12:163–166. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez J, Tuschl T. Genes Dev. 2004;18:975–980. doi: 10.1101/gad.1187904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarz DS, Tomari Y, Zamore PD. Curr Biol. 2004;14:787–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi Y, Denli AM, Hannon GJ. Mol Cell. 2005;19:421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caudy AA, Ketting RF, Hammond SM, Denli AM, Bathoorn AM, Tops BB, Silva JM, Myers MM, Hannon GJ, Plasterk RH. Nature. 2003;425:411–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R. Nature. 2005;436:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature03868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hammond SM, Boettcher S, Caudy AA, Kobayashi R, Hannon GJ. Science. 2001;293:1146–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1064023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumberger N, Baulcombe DC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11928–11933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505461102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song JJ, Hammond SM, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rand TA, Ginalski K, Grishin NV, Wang X. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14385–14389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405913101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sen GL, Blau HM. FASEB J. 2006;20:1293–1299. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6014rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hearne PQ, Knorr DA, Hillman BI, Morris TJ. Virology. 1990;177:141–151. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]