Abstract

Despite recent progress in our understanding of carotenogenesis in plants, the mechanisms that govern overall carotenoid accumulation remain largely unknown. The Orange (Or) gene mutation in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var botrytis) confers the accumulation of high levels of β-carotene in various tissues normally devoid of carotenoids. Using positional cloning, we isolated the gene representing Or and verified it by functional complementation in wild-type cauliflower. Or encodes a plastid-associated protein containing a DnaJ Cys-rich domain. The Or gene mutation is due to the insertion of a long terminal repeat retrotransposon in the Or allele. Or appears to be plant specific and is highly conserved among divergent plant species. Analyses of the gene, the gene product, and the cytological effects of the Or transgene suggest that the functional role of Or is associated with a cellular process that triggers the differentiation of proplastids or other noncolored plastids into chromoplasts for carotenoid accumulation. Moreover, we demonstrate that Or can be used as a novel genetic tool to induce carotenoid accumulation in a major staple food crop. We show here that controlling the formation of chromoplasts is an important mechanism by which carotenoid accumulation is regulated in plants.

INTRODUCTION

Carotenoids are orange, yellow, and red pigments that exert a variety of critical functions in plants. They are essential components of photosynthetic systems in assisting light harvesting and in protecting the photosynthetic apparatus from photooxidative damage (Niyogi, 1999; Demmig-Adams and Adams, 2002). They serve as precursors for the biosynthesis of the plant hormone abscisic acid (Schwartz et al., 1997) and for the production of volatile compounds for fruit and flower flavor and aroma (Bouvier et al., 2003; Simkin et al., 2004). In addition, plant carotenoids are the primary dietary source of provitamin A and offer protection against the incidence of certain diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and age-related eye diseases (Mayne, 1996; Giovannucci, 1999).

The indispensable role of carotenoids in plants and the increasing interest in their health benefits to humans have prompted a significant effort to gain a better understanding of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants (Hirschberg, 2001; Sandmann, 2002; DellaPenna and Pogson, 2006; Howitt and Pogson, 2006). All the major genes involved in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway have been cloned from different plant species (Cunningham and Gantt, 1998). The availability of a large number of carotenoid biosynthetic genes has facilitated the recent progress in the metabolic engineering of carotenogenesis in plants (Fraser and Bramley, 2004; Taylor and Ramsay, 2005), such as in the cases of Golden Rice (Ye et al., 2000; Paine et al., 2005), Golden Canola seeds (Shewmaker et al., 1999), yellow potato (Ducreux et al., 2005), and plants with high-economic-value carotenoids (Stålberg et al., 2003; Ralley et al., 2004).

Carotenoids accumulate in high levels in chloroplasts and chromoplasts in plants. Distinctive regulatory mechanisms appear to be involved in the control of carotenogenesis in these plastids. In chloroplasts of green tissues, the regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis occurs in a coordinated manner with other cellular processes for the assembly of the photosynthetic apparatus (von Lintig et al., 1997; Park et al., 2002). Light is known to play a key role in controlling the formation of photosynthetic complexes. Mutations in components of the light signaling pathway have been shown to alter carotenogenesis (Mustilli et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2004; Davuluri et al., 2005). In chromoplasts of fruits and flowers, the synthesis and accumulation of specific carotenoids are controlled by developmental cues. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression appears to be a major mechanism by which the developmental control occurs (Giuliano et al., 1993; Ronen et al., 1999; Isaacson et al., 2002).

Despite significant progress in our understanding of carotenogenesis in plants, the control mechanisms regulating overall carotenoid biosynthesis and accumulation remain an enigma. Specifically, we do not know the regulatory genes that positively or negatively modulate carotenogenesis and the regulatory factors that govern carotenogenic gene expression in plants. Novel carotenoid mutants could provide useful tools for exploring the regulation of carotenogenesis in plants.

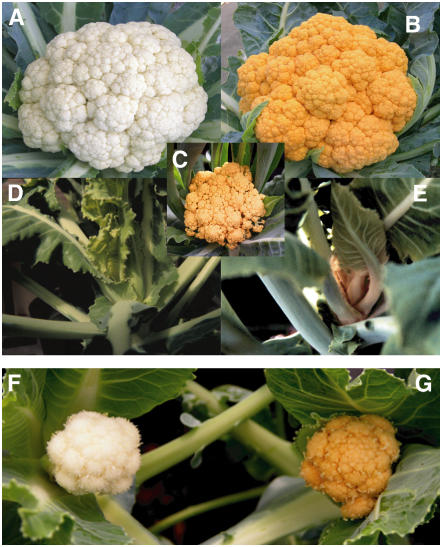

A spontaneous, semidominant Orange (Or) mutant in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var botrytis) represents an interesting genetic mutation that confers carotenoid accumulation in normally unpigmented tissues (Crisp et al., 1975; Dickson et al., 1988). It provides an excellent model to elucidate the regulatory control of carotenoid accumulation. The Or gene induces many tissues of the plant, most noticeably the white edible curd (Figure 1A) and shoot apical meristem (Figure 1D), to accumulate high levels of β-carotene, turning them orange (Figures 1B, 1C, and 1E). Plants that are heterozygous for Or possess bright orange coloration in these tissues and exhibit normal growth, while Or homozygous plants produce smaller curds with stunted growth, presumably due to unknown pleiotropic effects. The orange hue was observed to be due to the presence of massive, sheet-like structures in chromoplasts (Li et al., 2001; Paolillo et al., 2004). Or appears not to affect the biosynthetic capacity of carotenogenesis and causes no significant upregulation of genes required for β-carotene biosynthesis (Li et al., 2001, 2006). Hybrid Or cauliflower containing large amounts of β-carotene is commercially available.

Figure 1.

Phenotype of the Or Mutant and Complementation of the Orange Phenotype.

(A) Curd of wild-type cauliflower plant grown in the field.

(B) Curd of commercial orange cauliflower (Or/or) grown in the field. The Or heterozygous plants exhibit normal growth like the wild type with general curd sizes of 15 to 20 cm in diameter.

(C) Curd of Or homozygous mutant grown in the field. The homozygous mutant plants exhibit stunted growth with small curd sizes of 3 to 5 cm in diameter.

(D) Apical shoot of a 3-month-old wild-type cauliflower plant grown in a greenhouse.

(E) Apical shoot of a 3-month-old Or homozygous mutant plant grown in a greenhouse.

(F) and (G) Cauliflower plants transformed with the pBAR1 binary vector alone (F) or with the Or gene (G). Curds of transformants expressing the Or transgene show the orange phenotype. The transgenic plants were grown in a greenhouse for 4 months.

In this article, we report the positional cloning and functional characterization of the Or gene. We show that Or is likely a gain-of-function mutation and encodes a plastid-associated protein containing a Cys-rich domain found in DnaJ-like molecular chaperones. A functional role of Or involves the differentiation of noncolored plastids into chromoplasts, which provide the deposition sink for carotenoid accumulation. Furthermore, we demonstrate that Or works across different plant species in inducing carotenoid accumulation and thus can serve as a new genetic tool for improving the nutritional value in important food crops.

RESULTS

Positional Cloning of Or

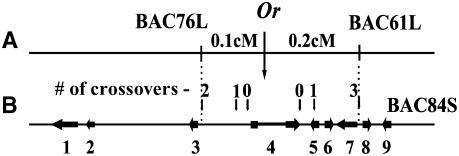

Our previous characterization of the Or mutant suggested that Or may represent a novel gene in regulating carotenoid accumulation in plants (Li et al., 2001). To investigate the molecular and biochemical basis of Or in regulating carotenoid accumulation, we initiated the isolation of Or by a map-based cloning strategy. Using an amplified fragment length polymorphism technique, we identified 10 amplified fragment length polymorphic markers closely linked to the Or locus and established a high-resolution genetic map of the Or region following analysis of 1632 F2 individuals (Li et al., 2003). To facilitate the isolation of Or, a cauliflower BAC library was constructed. Through four successive hybridization steps, a BAC contig encompassing Or was assembled. The Or locus was delimited into a genetic and physical interval of 0.3 centimorgan and 50 kb, respectively, within a single BAC clone, BAC84S (Li et al., 2003).

The entire BAC84S clone was sequenced, and nine putative genes were identified. Because Or was defined genetically between markers BAC76L and BAC61L (Figure 2A), we fine-mapped the putative genes between these two marker sequences, which encompass a physical distance of ∼23 kb. Four new restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) markers within the 23-kb fragment were developed based on the BAC sequence. While putative gene 5 and a fragment between genes 3 and 4 were mapped on opposite sides of the Or locus with one recombination event, respectively, gene 4 was found to cosegregate with the Or locus (Figure 2B). Sequence analysis of this gene revealed a 4.7-kb copia-like long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposon insertion in the Or mutant allele. Subsequent sequencing of the wild-type allele confirmed this insertion in the Or mutant allele. Thus, fine genetic mapping, along with the identification of a large retrotransposon insertion in the mutant allele, defined a single candidate gene for Or.

Figure 2.

Identification of the Or Candidate Gene.

(A) Schematic diagram of the high-resolution genetic map of the Or region. The Or locus is flanked by the markers BAC76L and BAC61L with a genetic distance of 0.3 centimorgan.

(B) Schematic diagram of the 50-kb BAC84S insert. Horizontal arrows represent the orientation and relative sizes of the nine putative genes predicted by the GENSCAN program. Small vertical arrows denote the positions of cross-over events with the number of recombinant plants indicated above the arrows. The dashed lines align the location of BAC76L and BAC61L markers to BAC84S sequence. Gene 4 was found to cosegregate with the Or locus.

Functional Complementation of the Orange Phenotype by the Or Candidate Gene

To confirm the identity of the Or candidate gene, a 9.2-kb genomic fragment (GenBank accession number DQ_482460) containing only the candidate gene with the retrotransposon insertion was transformed into wild-type cauliflower plants by Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated transformation (Cao et al., 2003). More than 20 independent T0 transformants expressing the Or transgene and the vector-only control construct were generated. While the vector-only controls showed the wild-type phenotype (Figure 1F), the Or transformants converted the white color of curd tissue into the distinct orange color (Figure 1G). HPLC analysis confirmed that the color change in the curds was indeed associated with the accumulation of β-carotene (data not shown). Thus, these results demonstrate the successful cloning of Or.

Structural Analysis of Or

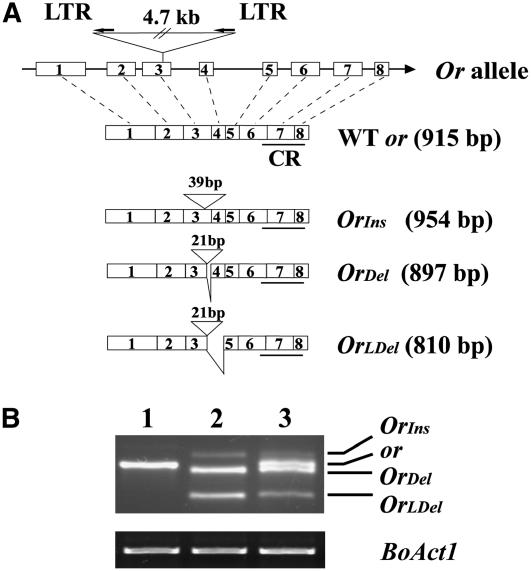

The full-length cDNAs of Or and its wild-type counterpart (or) were isolated following 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends using RNA isolated from curd tissue. The cDNA and the deduced amino acid sequence of the wild-type or gene are shown in Supplemental Figure 1 online. Alignment of the wild-type cDNA with its genomic sequence defined a gene structure of eight exons and seven introns (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Schematic Presentation of the Or Allele and Three Alternatively Spliced Transcripts, and Relative Abundance of These Transcripts.

(A) The top diagram depicts the Or allele with the 4.7-kb LTR retrotransposon insertion site and orientation. Open boxes with numbers represent exons, and solid lines represent introns. The bottom diagrams show the structural alteration of the three alternatively spliced transcripts in comparison with the wild-type transcript. The number of nucleotides inserted in each Or variant and the location of exon-skipping deletion sites are indicated. OrIns, insertion; OrDel, deletion; OrLDel, large deletion; CR, Cys-rich domain.

(B) RT-PCR amplification of the cDNA pools from curds of the wild-type (lane 1), Or homozygous (lane 2), and heterozygous plants (lane 3). The presence of three different sizes of Or transcripts with OrDel being the most abundant one were revealed using the primers P-M1-F and P-M1-R (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). Bo Act1 serves as an internal control. PCR amplification of 30 cycles for Or transcripts and 22 cycles for Bo Act1 was performed as detailed in Methods.

Retrotransposons are widely distributed in the plant kingdom and account for a large portion of some plant genomes (Feschotte et al., 2002). Recently, Alix et al. (2005) estimated that 60 to 570 copies of copia-like retrotransposons are present in the B. oleracea genome. We also observed a high copy number of copia-like retrotransposons in our DNA gel blots when using the retrotransposon insertion fragments as probes (data not shown). The insertion of a copia-like LTR retrotransposon in the Or allele occurs in exon 3 and results in the production of three alternatively spliced Or transcripts (Figure 3; see Supplemental Figure 2 online). Analysis of these transcripts revealed that the retrotransposon sequence had been excised, leaving a 39-bp footprint in one insertion transcript (insertion, OrIns) and a 21-bp footprint in another two exon-skipping deletions (deletion, OrDel, and large deletion, OrLDel) as depicted in Figure 3A. PCR analysis of the Or mutant cDNA pool using primers close to the insertion site revealed that OrDel is the most abundant transcript (Figure 3B, lane 2). As was found for the maize (Zea mays) waxy gene (Varagona et al., 1992), despite the insertions of the retrotransposon footprint sequences and the deletions, all of the alternatively spliced transcripts code contiguous open reading frames and use the original translation stop codon to encode proteins (see Supplemental Figures 2 and 3 online). For simplicity and clarity of presentation, we use the nomenclature Or transcripts to describe the mRNA for all the variants of the alternatively spliced transcripts and OR for the potential translated products. The wild-type gene and its product are denoted by or and ORWT protein, respectively.

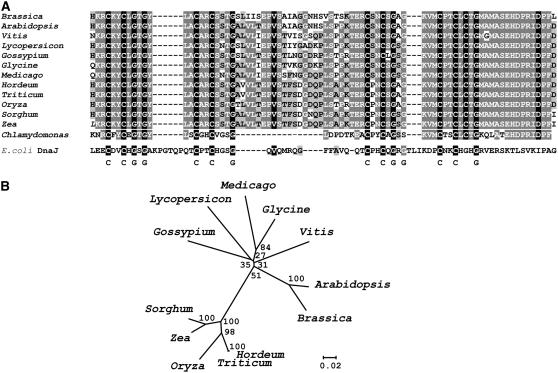

ORWT Is a DnaJ Cys-Rich Domain-Containing Protein and Is Highly Conserved in Divergent Plant Species

The open reading frame of the wild-type gene is predicted to encode a protein of 305 amino acids with an estimated molecular mass of 33.5 kD. The deduced protein is predicted to be plastid targeted and has two putative transmembrane domains. The most prominent feature of ORWT is that it contains a Cys-rich zinc finger domain that is highly specific to DnaJ-like molecular chaperones (Miernyk, 2001) (Figure 4A). DnaJ-like proteins represent a large structurally diverse protein family that participates in protein folding, protein assembly and disassembly, and translocation into organelles (Cheetham and Caplan, 1998; Hartl and Hayer-Hartl, 2002). The Cys-rich zinc finger domain has four repeats of the motif CxxCxGxG with the eight Cys residues and five of the Gly resides absolutely conserved from Archaea to humans (Martinez-Yamout et al., 2000). As ORWT lacks the N-terminal J domain that defines the DnaJ-like molecular chaperones (Miernyk, 2001), ORWT is more likely a Cys-rich zinc finger protein for a unique cellular function.

Figure 4.

Multiple Sequence Alignments of the DnaJ Cys-Rich Domain and Phylogenetic Tree of Or Homologs.

(A) The alignment includes the comparison of the sequences of 13 plant ORWT homologs with an E. coli DnaJ protein. The amino acid sequences were translated from GenBank NM_203246 for Arabidopsis thaliana, from The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) Plant Transcript Assemblies Database numbers TA6709_29760 for Vitis vinifera, TA6503_4081 for Lycopersicon esculentum, TA2322_3635 for Gossypium hirsutum, TA4160_3880 for Medicago truncatula, TA6293_3847 for Glycine max, TA5326_4513 for Hordeum vulgare, TA19897_4565 for Triticum aestivum, TA394_4530 for Oryza sativa, TA4814_4558 for Sorghum bicolor, TA16877_4577 for Zea mays, and TA9883_3055 for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, and aligned with an E. coli DnaJ protein (GenBank accession number NP_414556). Conserved residues are shaded. The highly conserved Cys-rich domain of four repeats of the CxxCxGxG motif are indicated. All of the ORWT homologs contain eight Cys and six Gly residues.

(B) The phylogenetic analysis was performed on the alignment of the full-length ORWT homologs shown in Supplemental Figure 4 online using the MEGA 3 program. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with the neighbor-joining method. The bootstrap values were determined from 1000 trials. Numbers along branches indicate the percentage of bootstrap support. The length of the branch lines indicates the extent of divergence according to the scale (relative units) at the bottom.

The or gene appears to be plant specific and shares no significant sequence similarities with genes from bacteria, cyanobacteria, yeast, or other organisms. Homologs are present in all plant species that have been examined, including the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas. Protein sequence alignment revealed that with the exception of the targeting sequence region, ORWT and its homologs exhibit exceptional conservation (Figure 4A; see Supplemental Figure 4 online). Although ORWT contains the highly conserved Cys-rich domain of DnaJ proteins, the overall amino acid sequence similarity between ORWT and an Escherichia coli DnaJ protein is low (e.g., 11.1%). Phylogenetic analysis indicates that ORWT is related most closely to the homolog from Arabidopsis thaliana (At5g61670) (Figure 4B).

The or RNA Interference Lines Do Not Exhibit the Mutant Phenotype

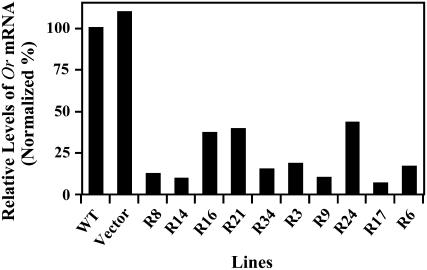

To obtain information on whether Or is a dominant negative mutation whose gene product is nonfunctional and interferes with the function of the wild-type gene product, we generated >30 independent or RNA interference (RNAi) transgenic lines in cauliflower by expressing a transgene that encodes double-stranded or RNA. Analysis of these or RNAi transgenic lines showed that in comparison with wild-type and vector-only controls, these transformants displayed greatly reduced levels of or transcript, ranging from 7 to 43% of that in the wild type (Figure 5). Examination of these or RNAi plants revealed no observable Or mutant phenotype or increased levels of carotenoid accumulation (data not shown). These results suggest that Or is most likely not a dominant negative mutant of the wild-type or gene.

Figure 5.

Relative Expression Levels of or in the or RNAi Lines and Control Plants.

The transcript levels for or in curd tissue were measured using semiquantitive RT-PCR with the primers of P-M1-F and P-M1-R. The levels of each transcript normalized against the internal control of Bo Act1 are presented as percentages of the wild-type control, which is set at 100%. Samples were nontransformed wild-type control, pFGC5941 vector alone transformed control (Vector), and independent or RNAi transgenic lines.

Expression of the Or Gene and Protein

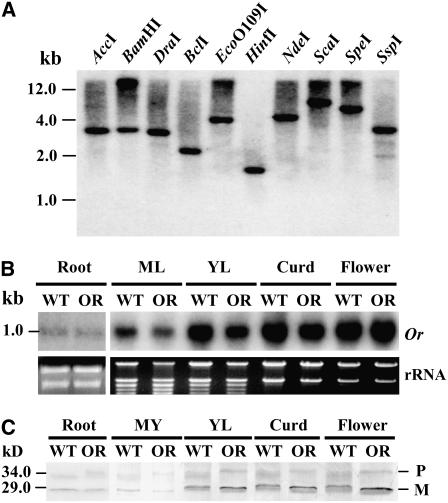

To better understand the molecular basis of Or action, the expression of Or was examined. Or represents a single-copy gene in the cauliflower genome (Figure 6A). Probing the mRNA from wild-type and mutant plants with either the 5′ or 3′ end fragment of Or revealed no notable smaller or larger transcripts, suggesting that the retrotransposon insertion does not cause the production of truncated or chimeric transcripts. Due to the small size difference among the Or variants and between the Or variants and the wild-type or transcript, we detected similar sizes of transcripts in both wild-type and mutant plants (Figure 6B). Or was found to be expressed highly in young leaves, curds, and flower buds at a comparable abundance to the wild-type or mRNA. The steady state transcript levels were significantly less in either mature leaves or roots.

Figure 6.

Molecular Characterization of Or.

(A) DNA gel blot analysis showing that Or represents a single gene in the cauliflower genome. Genomic DNA (10 μg) from leaves of the wild type was digested with restriction enzymes as indicated. DNA size markers are at the left.

(B) RNA gel blot analysis of Or expression in different tissues of wild-type and Or mutant plants. Total RNA samples were used for the detection of Or transcript levels. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide as loading control (25S and 18S rRNA). ML, mature leaf; YL, young leaf.

(C) Protein gel blot analysis of OR proteins in different tissues of the wild type and Or mutant. OR proteins were detected with antigen-specific antibodies as described in Methods. The bands around 34 kD are likely the unprocessed precursors (P). The band around 29 kD represents mature protein (M). Protein size standards are indicated at the left.

To investigate OR protein expression, we overexpressed ORWT as a His-fusion protein and raised a polyclonal antibody against it. Protein gel blot analysis using the purified antigen-specific antibody revealed that the protein was abundant in young leaves, curds, and flower buds, showing a similar general expression pattern as was seen for transcript abundance (Figure 6C). While ORWT is predicted to be a 33.5-kD protein, the predicted sizes of the OR variants ORIns, ORDel, and ORLDel are 34.8, 32.6, and 29.6 kD, respectively. Low levels of what are most likely unprocessed proteins corresponding to the predicted sizes of ORWT and OR variants were usually observed, except for ORLDel. It is possible that the ORLDel protein is either not translated or is not stable. The slightly smaller size of the mature OR protein in the mutant versus the protein in the wild-type plants (∼29 kD) possibly results from the most abundant transcript OrDel-encoded form of the OR protein.

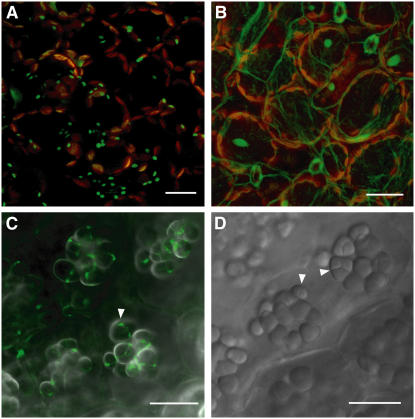

ORWT Is Targeted to Plastids

The ORWT protein is predicted to have a transit peptide. To define the potential function of Or, we experimentally determined the subcellular localization of ORWT in plants. The coding region of the wild-type or gene was fused to a modified green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (von Arnim et al., 1998) and transformed into Arabidopsis. Examination of two independent or-GFP transgenic lines revealed that the fusion protein was accumulated predominantly as green dots in the epidermal cells of young leaves (Figure 7A). These localized accumulations of ORWT-GFP protein are most likely associated with leucoplasts, which are known to exist in nongreen differentiated tissues (e.g., the epidermis) (Gunning and Steer, 1996). The ORWT-GFP fusion is unlikely localized in the other organelles, such as mitochondria or peroxisomes, due to the fact that the green fluorescent signal was observed only in the epidermal cells of the leaf tissue. In addition, the fusion protein appears not to accumulate in the fully developed chloroplasts since no increased GFP signal was observed in the transgenic lines expressing ORWT-GFP in comparison with the nontransformed controls. No specific organelle targeting was observed in the GFP vector-only control (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Subcellular Localization of ORWT-GFP in Stable Transgenic Arabidopsis Lines.

(A) Projection image of z axis series of GFP (green) and chlorophyll (red) fluorescence in cells of young leaves expressing the or-GFP transgene. The small green dots were observed in the epidermal cells and are most likely localized to leucoplasts.

(B) Projection image of z axis series of GFP (green) and chlorophyll (red) fluorescence in cells of young leaves expressing GFP alone as the control. No specific organelle targeting was observed.

(C) Image of the GFP signal overlaid on a transmitted light image in young developing seeds from the or-GFP transgenic line. The globular intracellular inclusions resemble amyloplasts. The green fluorescence appears to be concentrated to the site of plastid division.

(D) Transmitted light image of cells from nontransformed young developing seeds showing amyloplasts within cells. The arrowheads point to amyloplast division sites.

These images represent multiple analyses of two independent transgenic lines. Bars = 20 μm.

In the developing seeds of transgenic Arabidopsis, the ORWT-GFP fluorescent signal was found to be associated with globular intracellular inclusions (Figure 7C). These inclusions were observed in both the or-GFP transgenic lines and the wild-type controls (Figure 7D). They resemble the plastids that have been previously demonstrated to be amyloplasts in Arabidopsis wild-type seeds at 8 d after pollination (Western et al., 2000). Furthermore, the GFP fluorescence appears to be concentrated at the amyloplast division sites (Figure 7C). These results suggest that ORWT is targeted to nongreen plastids but appears not to accumulate in chloroplasts.

Or Is Expressed Highly in Tissues Normally Rich with Proplastids

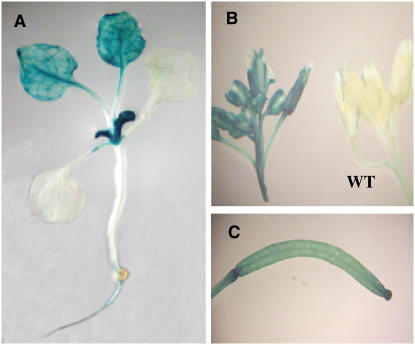

To further characterize Or, a 2.0-kb promoter sequence of Or was translationally fused to the uidA reporter gene encoding a β-glucuronidase (GUS) protein and transformed into Arabidopsis. High levels of GUS expression were found in apical shoots and very young leaves (Figure 8A), which are the tissues rich in proplastids (Pyke, 1997). In addition, GUS activity was also observed in the developing leaves, flower buds, siliques, and young roots (Figures 8A to 8C). The overall GUS expression pattern in the transgenic Arabidopsis plants recapitulated the Or mRNA expression pattern in cauliflower. Thus, the Or-induced carotenoid accumulation in apical shoot and curd tissues in cauliflower is likely due to specific gene expression in tissues normally rich with proplastids and/or other noncolored plastids.

Figure 8.

Localization of GUS Activity in Stable Transgenic Arabidopsis Lines Expressing ProOr:GUS.

(A) A 3-week-old transgenic seedling stained for GUS activity. GUS activity was highly expressed in shoots and young leaves and was also observed in the developing leaves and roots.

(B) and (C) Flower buds (B) and young silique (C) showing GUS activity. WT, nontransformed control.

These images are representative results of multiple plants from four independent transgenic lines.

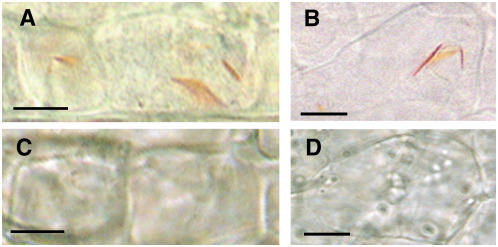

The Or Transgene Induces Chromoplast Formation

To further study the functional role of Or in carotenoid accumulation, we examined the cytological effects of the Or transgene in transgenic plants expressing the Or allele with light microscopy. We found that inducing Or into wild-type cauliflower leads to the formation of chromoplasts in the curd tissue (Figures 9A and 9B). These chromoplasts are seen as needle-like orange structures within each cell. They closely resemble those observed in the Or homozygous mutant (Li et al., 2001; Paolillo et al., 2004). These chromoplasts express the same full spectrum and details of morphological forms and the same dichroism for carotenoid accumulation. In addition, the Or transgene also confers the limitations on plastid division, with one or two large chromoplasts per affected cell in the curd meristem and curd pith of the Or transformants (Figures 9A and 9B). This reduction in plastid division is similar to the phenotype found in the Arabidopsis plastid division mutant, arc6, which has one or two enlarged plastids per cell (Robertson et al., 1995). The orange organelles were not observed in the wild-type controls (Figures 9C and 9D).

Figure 9.

Cytological Analysis of the Curd Tissue from Or Transformants and Wild-Type Controls.

(A) and (B) Individual curd meristematic (A) and curd pith immature parenchyma cells (B) of the transgenic cauliflower expressing the Or transgene. The one or two yellow needle-like structures within each cell represent chromoplasts containing high levels of carotenoid deposits.

(C) Curd meristematic cells of wild-type cauliflower.

(D) Wild-type curd pith immature parenchyma cells showing multiple organelles without orange color.

Bars = 5 μm.

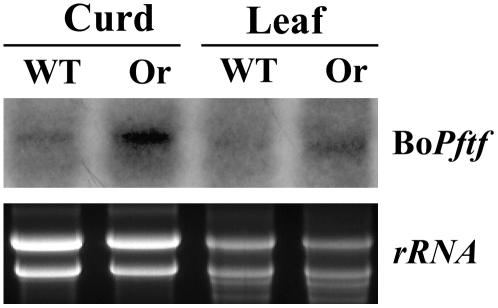

The Or Mutant Has an Increased Expression of Bo Pftf Involved in Chromoplast Differentiation

The presence of Or triggers the differentiation of plastids in the shoot and curd inflorescence meristems into one or two large chromoplasts (Figures 9A and 9B). A previous study revealed that the chromoplasts are the only plastids in the affected cells in the mutant (Paolillo et al., 2004). To further investigate the effect of Or on chromoplast differentiation, we examined the expression of the cauliflower homolog of Pftf, the gene that has been shown to be involved in chromoplast differentiation in red pepper (Capsicum annuum) (Hugueney et al., 1995). RNA gel blot analysis of the transcript levels from curd and leaf tissues of the wild type and the Or mutant revealed that the mutant has an increased level of expression of the Bo Pftf gene (Figure 10), implying a possibly enhanced chromoplast biogenesis activity in the Or mutant plants.

Figure 10.

Expression of the Cauliflower Homolog of the Pepper Pftf Gene.

RNA gel blot analysis of the transcript levels for the cauliflower homolog of the chromoplast biogenesis gene Pftf. Total RNA samples (10 μg) were used for the detection of Bo Pftf abundance. The ethidium bromide–stained rRNA was used as an internal control.

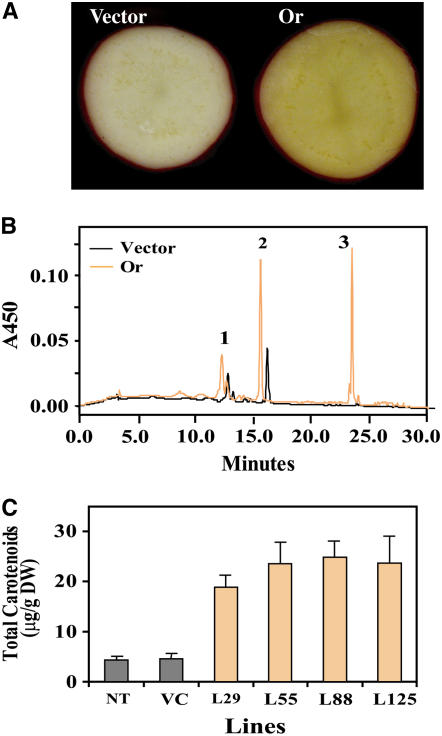

Or Functions across Species to Increase Carotenoid Accumulation

To examine whether Or can be used as a new genetic tool to enhance carotenoid content in a major staple crop, Or was transformed into potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants under the control of a granule-bound starch synthase gene promoter (Van der Steege et al., 1992) to obtain tuber-specific expression. Remarkably, expression of Or in the transgenic potato tubers results in the production of orange-yellow tubers (Figure 11A). HPLC analysis confirmed that this color change is indeed associated with enhanced levels of carotenoids, including the accumulation of β-carotene that is present at negligible amounts in the controls (Figure 11B). The total carotenoid contents in the tubers expressing the Or transgene were sixfold higher than those in the controls (Figure 11C). This successful transformation result demonstrates that Or functions across plant species and can be used as a novel molecular tool to enrich carotenoid contents for improving the nutritional value of crops.

Figure 11.

Enhancing Carotenoid Accumulation by Expression of Or in Transgenic Potato Tubers.

(A) Cross section of potato tubers transformed with the empty vector (vector) and the Or gene (Or). Orange-yellow color was observed in the Or transformant.

(B) HPLC elution profiles of pigments extracted from transgenic potato tubers expressing either the empty vector or the Or transgene. The elution profile of the vector control was shifted slightly for easy comparison. 1, violaxanthin; 2, lutein; 3, β-carotene.

(C) Total carotenoid levels in nontransformed control (NT) and transgenic potato tubers. The carotenoid levels represent the averages from at least five individual tubers. Error bars indicate sd. VC, vector control; L#, individual Or transgenic lines; DW, dry weight.

DISCUSSION

The spontaneous, single-locus Or gene mutation in cauliflower confers high levels of β-carotene accumulation in tissues where the accumulation of carotenoids is normally repressed. In this study, we have successfully isolated the gene representing Or by map-based cloning and verified its role in conferring carotenoid accumulation via functional complementation in wild-type cauliflower. We show that Or encodes a plastid-associated protein with a DnaJ Cys-rich domain (Miernyk, 2001) and is expressed highly in tissues normally rich in proplastids or noncolored plastids.

The Functional Role of Or Is Associated with Chromoplast Formation

Or encodes a novel regulatory gene involved in conferring carotenoid accumulation in the cauliflower mutant plant. Several lines of evidence suggest that Or functions in association with a cellular process that triggers the differentiation of proplastids and/or other noncolored plastids into chromoplasts, which in turn provide a metabolic sink for carotenoid accumulation. First, Or imposes its strong effect on carotenoid accumulation in the apical shoot meristems and the outer periphery of curd (Figures 1B, 1C, and 1E), the tissues that normally are rich in proplastids and leucoplasts (Pyke, 1997). Second, the gene is expressed highly in these tissues (Figure 6), and ORWT protein was found to be associated with nongreen plastids (Figure 7). Third, the presence of Or induces the formation of one or two large chromoplasts per affected cell (Figure 9). These chromoplasts were found to be the only plastids in the orange cells (Paolillo et al., 2004). Fourth, concomitantly with chromoplast formation, we observed that the Or mutant has an increased expression of the cauliflower homolog of Pftf (Figure 10), a gene known to be involved in chromoplast differentiation in red pepper (Hugueney et al., 1995).

High levels of carotenoids are accumulated in chromoplasts that act as a metabolic sink. There is evidence demonstrating that the biosynthesis of a structure that facilitates the storage of carotenoids provides a driving force for carotenoid accumulation by creating a chemical disequilibrium to effectively sequester the end products of synthesis (Rabbani et al., 1998; Vishnevetsky et al., 1999). Previously we have shown that the Or mutant exhibits no increased expression of carotenoid biosynthetic genes, suggesting that the Or-induced carotenoid accumulation is not due to an increased capacity for carotenoid biosynthesis (Li et al., 2001). Thus, the accumulation of carotenoids in both the Or cauliflower mutant and transgenic potato is likely the result of an increase in sink strength that facilitates the sequestration of carotenoids.

OR Also Affects Chromoplast Division

Apart from its primary effect on chromoplast differentiation and the associated carotenoid accumulation, Or may exert an additional control on plastid division. Or confers a plastid division arrest phenotype resembling the Arabidopsis plastid division mutant arc6, which shows only one or two enlarged proplastids per cell in the shoot apical meristems (Robertson et al., 1995). In contrast with the arc6 mutant that also contains one or two large chloroplasts in leaf mesophyll cells, the Or mutant has a normal number of chloroplasts in leaves (data not shown), suggesting that chloroplast division is normal once the effects of Or are overcome by the leaf developmental program. Recently, ARC6 was shown to encode a DnaJ-like plastid protein containing an atypical J-like domain localized to the plastid division midpoint (Vitha et al., 2003). Like the ARC6 protein, ORWT also appears to be expressed highly at the plastid division site. Plastid division is orchestrated by multiple proteins (Osteryoung and Nunnari, 2003). It is likely that ORWT constitutes a new component of the plastid division machinery.

OR Might Exert Its Functional Role through Protein–Protein Interactions

Chromoplasts can be derived from chloroplasts, proplastids, and other nonphotosynthetic plastids in plants (Marano et al., 1993). Chromoplast differentiation involves complex cellular processes, leading to the formation of the specialized metabolic and sequestering structures (Camara et al., 1995). A new set of proteins during differentiation of chloroplasts to chromoplasts in flowers and fruits has been identified (Deruere et al., 1994; Hugueney et al., 1995; Vishnevetsky et al., 1996). However, the essential biochemical and molecular processes that are associated with the differentiation of noncolored plastids into chromoplasts are unknown. OR may define an important component of the cellular processes for the differentiation and division of chromoplasts.

The predicted OR proteins and ORWT contain the DnaJ Cys-rich domain, which is known to mediate protein–protein interactions (Banecki et al., 1996; Szabo et al., 1996). The striking homology of the Cys-rich domain between OR and DnaJ-like proteins suggests that OR may exert its functional role in association with the molecular chaperone system through protein–protein interactions. As OR lacks the J domain essential for biological function of chaperones (Miernyk, 2001) and is not a heat shock–inducible protein (data not shown), it is unlikely that OR acts as a molecular chaperone. The only protein of known function from plants that contains just the Cys-rich domain of DnaJ-like proteins is maize BSD2 (Brutnell et al., 1999). This protein is postulated to bind the newly translated large subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) and acts together with a DnaJ chaperone system for the folding or assembly of the Rubisco holoenzyme complex (Brutnell et al., 1999). By analogy, it is possible that ORWT normally works in association with a DnaJ-like protein to bind to a protein(s) specific for the plastid differentiation/division in meristematic tissue during normal plant growth and development. The mutation of OR could alter the binding ability to its target protein(s), causing the differentiation of proplastids into chromoplasts. Alternatively, the mutation may create a novel functionality for the protein, which makes it essential for chromoplast biogenesis. Recently, Liu et al. (2005) showed that the DnaJ chaperone system directly interacts with VIPP1 for the biogenesis of thylakoid membranes. Further experiments to identify and functionally characterize proteins associated with OR will be critical for a full understanding of the precise mechanism by which Or triggers chromoplast formation for the associated carotenoid accumulation.

A second or-like gene was also isolated from cauliflower. It shares 55% nucleotide sequence identity to Or and encodes a protein of 313 amino acids. Whether or not the or-like gene is associated with plastid differentiation is unclear. However, the conferring of chromoplast formation with the associated carotenoid accumulation by the single gene mutation of Or implies that the two genes may not be functionally redundant.

Or Appears to Be a Gain-of-Function Mutation

The semidominant phenotype of a mutant can be due to (1) a gain-of-function mutation whose gene product becomes constitutively active or gains a novel function normally not found in the wild-type protein; (2) a dominant negative mutation whose gene product adversely affects the normal wild-type gene product; or (3) a loss-of-function mutation (i.e., haploinsufficient) where the wild-type allele cannot compensate for the loss-of-function allele. The fact that expression of the Or transgene confers carotenoid accumulation in wild-type cauliflower implies that Or is unlikely to be haploinsufficient. To determine whether Or is a dominant negative mutant, silencing the wild-type or gene could be informative. Our results showed that none of the or RNAi transgenic lines exhibited the observed Or mutant phenotype. In addition, we also overexpressed the wild-type or gene under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Four independent transgenic lines showing high levels of or transcripts were obtained. None of these transgenic lines exhibited the characteristic features of the Or mutant with enhanced levels of carotenoid accumulation (D.M. O'Halloran and L. Li, unpublished data). These results suggest that Or is not a dominant negative mutant of the wild-type or gene but is likely a gain-of-function mutation that positively controls carotenoid accumulation.

As Or is likely a gain-of-function mutation, we reasoned that there was a possibility that one of the alternatively spliced transcripts, especially the most abundant form, OrDel, might play a major role in conferring carotenoid accumulation in the Or mutant. To examine this possibility, we generated >20 independent transgenic lines expressing high levels of the individual alternatively spliced transcript. However, none of these transformants exhibited the orange phenotype and the associated carotenoid accumulation in the curd tissue (D.M. O'Halloran and L. Li, unpublished data), suggesting that the Or-induced carotenoid accumulation may require the expression of more than one alternatively spliced transcript. There is evidence that multiple alternatively spliced transcripts are required for carrying out particular functions in plants (Zhang and Gassmann, 2003).

Use of Or for Improving Crop Nutritional Value

Carotenoids provide important nutrients and antioxidants for human diets. Increasing carotenoid levels in major staple crops are expected to have a broad and significant impact on human nutrition and health (Fraser and Bramley, 2004). A breakthrough in the metabolic engineering of a crop to increase its provitamin A content has been achieved in Golden Rice by expression of genes in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway (Ye et al., 2000; Paine et al., 2005). In nearly all of the cases except one (Davuluri et al., 2005), the metabolic engineering of carotenoid biosynthesis has focused solely on the manipulation of expression of carotenogenic genes. In many cases, this is insufficient to achieve the desired levels of carotenoid enhancement in plants (Fraser and Bramley, 2004; Howitt and Pogson, 2006). Here, we show that Or as a novel regulatory gene functions across different plant species to enhance carotenoid accumulation. The demonstration of significantly increased carotenoid levels in transgenic potato provides strong evidence for the potential use of Or for the genetic engineering of carotenoid contents in major staple food crops. Manipulating the formation of chromoplasts for carotenoid accumulation, together with increased expression of the catalytic components of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, may prove to be a more effective strategy for enhancing carotenoid levels in food crops to the levels required for optimal human nutrition and health.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var botrytis) plants used in this study include the homozygous wild-type cultivar Stovepipe (wild type, genotype oror), the homozygous mutant line 1227 (Or, genotype OrOr), and a heterozygous line (Oror) that was produced from a cross between the two homozygous lines. A mapping population of F2 individuals was generated from selfing of the heterozygous plants. Plants were grown in a greenhouse at 24°C under a 14-h-light/10-h-dark cycle. Leaf and curd samples for DNA, RNA, and protein extraction and for HPLC analysis were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use.

Nucleic Acid Analysis

For DNA gel blot analysis, genomic DNA (10 μg) isolated from leaf tissue of cauliflower plants was digested with restriction enzymes, separated on 0.8% agarose gels, and blotted onto Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham). Prehybridization, hybridization, and washing of the membranes were conducted as previously described (Li et al., 2001).

For RNA gel blot analysis, total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA samples (20 μg each) were separated on formaldehyde agarose gels and transferred onto Hybond N+ membranes. Equal loading of the samples was monitored by ethidium bromide staining of the rRNA.

For semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis, total RNA (2 μg) was primed with oligo(dT) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The cDNA concentrations in different samples were normalized based on the amplification of Bo Act1 (a cauliflower homolog of Arabidopsis thaliana actin gene; GenBank accession number AF044573). The number of cycles for amplification of the target genes was optimized to ensure amplification at liner range. Primer sequences used were as follows: Bo Act1 forward, 5′-CCGAGAGAGGTTACATGTTCACCAC-3′; Bo Act1 reverse, 5′-GCTGTGATCTCTTTGCTCATACGGTC-3′; or gene forward (P-M1-F), 5′-GAAGGACCTGAAACAGTACAGGACTTTGCC-3′; and or gene reverse (P-M1-R), 5′-CCAGTTCCTAGACAGTATTTGCATCTCTTGTG-3′. Quantification was performed using AlphaEaseFC (Alpha Innotech).

Identification of Candidate Gene Cosegregating with Or

The entire BAC84S clone was sequenced by the MWG Sequencing Service. The putative genes were predicted based on the program GENSCAN (http://genes.mit.edu/GENSCAN.html). Primers were designed based on the BAC sequence, and the amplified DNA fragments were used as probes for RFLP maker development (Li and Garvin, 2003). The newly developed RFLP markers were used for fine mapping to identify candidate genes that cosegregated with Or.

Isolation of Or cDNA and Analysis of the Sequences

Total RNA (2 μg) was used for reverse transcription by the strategy of 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends using the Smart RACE cDNA amplification kit (Clontech). Full-length cDNAs were amplified from cDNA pools of wild-type and the mutant plants with PfuUltra DNA polymerase (Stratagene), subcloned into pCR-Blunt-II vector (Invitrogen), and sequenced.

DNA and protein sequences were analyzed using the Lasergene program (DNASTAR) and Vector NTI (Invitrogen). TargetP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/) and ChloroP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/) were used for the predication of subcellular localization of the ORWT protein. InterProScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/InterProScan/) was employed for the prediction of functional domains of the protein. Sequences of ORWT homologs from other plant species were obtained by BLAST searches of the or cDNA against TIGR Unique Gene Indices (http://tigrblast.tigr.org/tgi). The aligned sequences were manually edited by GeneDoc (http://www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc). Phylogenetic analysis was performed on the alignment shown in Supplemental Figure 4 online using the program MEGA 3 (Kumar et al., 2004). Bootstrap values were determined from 1000 trials.

Plasmid Construction and Plant Transformation

To create the phenotypic complementation construct, a 9.2-kb DNA fragment encompassing only the Or gene and the retrotransposon from BAC84S was digested with ScaI and SacI and subcloned into the binary vector pBAR1 (pGPTV-BAR containing the modified pBS cloning site, obtained from Jeffery Dangl's lab, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). To make a double-stranded RNAi construct for specifically silencing the wild-type or gene, a 450-bp fragment of the gene in antisense and sense orientations was constructed into the binary vector pFGC5941 obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (http://www.arabidopsis.org/).

To generate the construct for subcellular localization in plants, the coding region of the wild-type or cDNA was fused into a modified GFP gene under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter (von Arnim et al., 1998). The expression cassette was then inserted into the binary vector pCAMBIA1300 (CAMBIA). To create the ProOr:GUS construct, a 2.0-kb promoter sequence of the Or gene from Or homozygous plants was fused to the GUS coding sequence (Gan and Amasino, 1995) and subcloned into pCAMBIA1300. For the potato (Solanum tuberosum) transformation construct, Or genomic DNA starting from the ATG codon was amplified with PfuUltra DNA polymerase, fused behind the potato granule-bound starch synthase gene promoter (Van der Steege et al., 1992), and subcloned into the pBI101 vector.

The constructs and the empty vectors were electroporated into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 and transformed into Arabidopsis Columbia ecotype using a floral dipping method (Clough and Bent, 1998), into cauliflower wild-type hypocotyl explants following the method described by Cao et al. (2003), or into the potato cultivar Desiree (J. Van Eck, unpublished data) to generate stable transformants. Positive transformants were confirmed by PCR amplification of the selective markers.

Carotenoid Analysis

Carotenoids were extracted and analyzed following the method as described by Li et al. (2001). Quantification was performed using a calibration curve generated with commercially available β-carotene and lutein standards (Sigma-Aldrich).

Anti-OR Antibody Production and Purification

A truncated form of or without putative transit peptide sequence was inserted into pET-32a vector (Novagen) and pGEX 4T-1 (Amersham) vectors and transformed into Rosetta2 (DE3) cells (Novagen) for a high level of expression of His- and GST-ORWT proteins. Expression of the fusion proteins was induced by 1 mM isopropylthio-β-galactoside for 4 h at 37°C. His-OR and GST-OR were purified by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA superflow (Qiagen) and a Glutathione Sepharose 4B (Amersham) column, respectively. Purified His-OR fusion protein was used to inject rabbits for raising polyclonal anti-OR antibody at the Cornell Center for Animal Research and Education. Antigen-specific antibody was purified from immunoblots containing the purified GST-ORWT (Harlow and Lane, 1988).

Protein Gel Blot Analysis

Total proteins from plant tissues (100 mg) were extracted in 200 μL of CellLytic P (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and quantified using the RC DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Protein samples (30 μg) were loaded onto 15% SDS-PAGE gel and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (0.2 μm; Schleicher and Schuell). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with primary antigen-specific antiserum at 1:200 dilution and secondary AP-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Bio-Rad) at 1:3000 dilution. Western Blue Stabilized Substrate (Promega) was used for chromogenic detection.

Microscopic Detection of GFP Fluorescence and GUS Histochemical Staining

GFP fluorescent signal in the transgenic Arabidopsis plants was monitored with a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope. The fluorescence was excited by the 476-nm laser line and detected with the monochromator mirrors set to 500 to 564 nm. Chlorophyll fluorescence was monitored with the same excitation and with monochromator mirrors set to 660 and 710 nm. GUS staining of the transgenic plants was performed using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide as substrate following the published protocol (Jefferson et al., 1987).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data for the Or mutant allele and the Or transcripts from the wild type and mutant used in this article can be found in the GenBank data library under the following accession numbers: Or allele (DQ_482460), wild-type or cDNA (DQ_482456), OrIns (DQ_482457), OrDel (DQ_482458), and OrLDel (DQ_482459).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. cDNA and Deduced Amino Acid Sequences of the Wild-Type or Gene.

Supplemental Figure 2. Alignment of the Nucleotide Sequences of or, OrIns, OrDel, and OrLDel.

Supplemental Figure 3. Alignment of the Predicted Protein Sequences of ORWT, ORIns, ORDel, and ORLDel.

Supplemental Figure 4. Alignment of the Predicted Protein Sequences of ORWT Homologs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Giovannoni and J. Hua for their valuable comments; J. O'Neill, A. Combs, and S. Burke for their excellent technical assistance; Y. Hu for his help with HPLC analysis; R. Clark for photography; T. Thannhauser and Y. Yang for identification of OR protein by mass spectrometry; and D. Reed for providing field space and assistance in growing cauliflower. This work was supported in part by USDA National Research Initiative Grant 2001-03514.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Li Li (ll37@cornell.edu).

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Alix, K., Ryder, C.D., Moore, J., King, G.J., and Pat Heslop-Harrison, J.S. (2005). The genomic organization of retrotransposons in Brassica oleracea. Plant Mol. Biol. 59 839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banecki, B., Liberek, K., Wall, D., Wawrzynow, A., Georgopoulos, C., Bertoli, E., Tanfani, F., and Zylicz, M. (1996). Structure-function analysis of the zinc finger region of the DnaJ molecular chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 271 14840–14848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier, F., Suire, C., Mutterer, J., and Camara, B. (2003). Oxidative remodeling of chromoplast carotenoids: Identification of the carotenoid dioxygenase CsCCD and CsZCD genes involved in crocus secondary metabolite biogenesis. Plant Cell 15 47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutnell, T.P., Sawers, R.J.H., Mant, A., and Langdale, J.A. (1999). BUNDLE SHEATH DEFECTIVE2, a novel protein required for post-translational regulation of the rbcL gene of maize. Plant Cell 11 849–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camara, B., Hugueney, P., Bouvier, F., Kuntz, M., and Moneger, R. (1995). Biochemistry and molecular biology of chromoplast development. Int. Rev. Cytol. 163 175–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J., Brants, A., and Earle, E.D. (2003). Cauliflower plants expressing a cry1C transgene control larvae of diamondback moths resistant or susceptible to Cry1A, and cabbage loopers. J. New Seeds 5 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham, M.E., and Caplan, A.J. (1998). Structure, function and evolution of DnaJ: Conservation and adaptation of chaperone function. Cell Stress Chaperones 3 28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, P., Walkey, D.-G.A., Bellman, E., and Roberts, E. (1975). A mutation affecting curd colour in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis DC). Euphytica 24 173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, F.X., and Gantt, E. (1998). Genes and enzymes of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49 557–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davuluri, G.R., et al. (2005). Fruit-specific RNAi-mediated suppression of DET1 enhances carotenoid and flavonoid content in tomatoes. Nat. Biotechnol. 23 890–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DellaPenna, D., and Pogson, B.J. (2006). Vitamin synthesis in plants: Tocopherols and carotenoids. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57 711–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams, B., and Adams, W.W. (2002). Antioxidants in photosynthesis and human nutrition. Science 298 2149–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deruere, J., Romer, S., d'Harlingue, A., Backhaus, R.A., Kuntz, M., and Camara, B. (1994). Fibril assembly and carotenoid overaccumulation in chromoplasts: A model for supramolecular lipoprotein structures. Plant Cell 6 119–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, M.H., Lee, C.Y., and Blamble, A.E. (1988). Orange-curd high carotene cauliflower inbreds, NY 156, NY 163, and NY 165. HortScience 23 778–779. [Google Scholar]

- Ducreux, L.J.M., Morris, W.L., Hedley, P.E., Shepherd, T., Davies, H.V., Millam, S., and Taylor, M.A. (2005). Metabolic engineering of high carotenoid potato tubers containing enhanced levels of β-carotene and lutein. J. Exp. Bot. 56 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C., Jiang, N., and Wessler, S.R. (2002). Plant transposable elements: Where genetics meets genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, P.D., and Bramley, P.M. (2004). The biosynthesis and nutritional uses of carotenoids. Prog. Lipid Res. 43 228–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan, S., and Amasino, R.M. (1995). Inhibition of leaf senescence by autoregulated production of cytokinin. Science 270 1986–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci, E. (1999). Tomatoes, tomato-based products, lycopene, and cancer: Review of the epidemiologic literature. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91 317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano, G., Bartley, G.E., and Scolnik, P.A. (1993). Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis during tomato development. Plant Cell 5 379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning, B.E.S., and Steer, M.W. (1996). Plant Cell Biology, Structure and Function. (Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers).

- Harlow, E., and Lane, D. (1988). Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Hartl, F.U., and Hayer-Hartl, M. (2002). Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: From nascent chain to folded protein. Science 295 1852–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberg, J. (2001). Carotenoid biosynthesis in flowering plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howitt, C.A., and Pogson, B.J. (2006). Carotenoid accumulation and function in seeds and non-green tissues. Plant Cell Environ. 29 435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugueney, P., Bouvier, F., Badillo, A., d'Harlingue, A., Kuntz, M., and Camara, B. (1995). Identification of a plastid protein involved in vesicle fusion and/or membrane protein translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 5630–5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson, T., Ronen, G., Zamir, D., and Hirschberg, J. (2002). Cloning of tangerine from tomato reveals a carotenoid isomerase essential for the production of β-carotene and xanthophylls in plants. Plant Cell 14 333–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, R.A., Kavanagh, T.A., and Bevan, M.W. (1987). GUS fusions: Beta glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 6 3901–3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Tamura, K., and Nei, M. (2004). MEGA3, intergrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., and Garvin, D.F. (2003). Molecular mapping of Or, a gene inducing β-carotene accumulation in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis). Genome 46 588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., Lu, S., Cosman, K.M., Earle, E.D., Garvin, D.F., and O'Neill, J. (2006). β-Carotene accumulation induced by the cauliflower Or gene is not due to an increased capacity of biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 67 1177–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., Lu, S., O'Halloran, D.M., Garvin, D.F., and Vrebalov, J. (2003). High-resolution genetic and physical mapping of the cauliflower high-beta-carotene gene Or (Orange). Mol. Genet. Genomics 270 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., Paolillo, D.J., Parthasarathy, M.V., DiMuzio, E.M., and Garvin, D.F. (2001). A novel gene mutation that confers abnormal patterns of β-carotene accumulation in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis). Plant J. 26 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C., Willmund, F., Whitelegge, J.P., Hawat, S., Knapp, B., Lodha, M., and Schroda, M. (2005). J-domain protein CDJ2 and HSP70B are a plastidic chaperone pair that interacts with vesicle-inducing protein in plastids 1. Mol. Biol. Cell 16 1165–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Roof, S., Ye, Z., Barry, C., van Tuinen, A., Vrebalov, J., Bowler, C., and Giovannoni, J. (2004). Manipulation of light signal transduction as a means of modifying fruit nutritional quality in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 9897–9902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marano, M.R., Serra, E.C., Orellano, E.G., and Carrillo, N. (1993). The path of chromoplast development in fruits and flowers. Plant Sci. 94 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Yamout, M., Legge, G.B., Zhang, O., Wright, P.E., and Dyson, H.J. (2000). Solution structure of the cysteine-rich domain of the Escherichia coli chaperone protein DnaJ. J. Mol. Biol. 300 805–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne, S.T. (1996). Beta-carotene, carotenoids, and disease prevention in humans. FASEB J. 10 690–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miernyk, J.A. (2001). The J-domain proteins of Arabidopsis thaliana: An unexpectedly large and diverse family of chaperones. Cell Stress Chaperones 6 209–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustilli, A.C., Fenzi, F., Ciliento, R., Alfano, F., and Bowler, C. (1999). Phenotype of the tomato high pigment-2 mutant is caused by a mutation in the tomato homolog of DEETIOLATED1. Plant Cell 11 145–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi, K.K. (1999). Photoprotection revisited: Genetic and molecular approaches. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50 333–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteryoung, K.W., and Nunnari, J. (2003). The division of endosymbiotic organelles. Science 302 1698–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine, J.A., Shipton, C.A., Chaggar, S., Howells, R.M., Kennedy, M.J., Vernon, G., Wright, S.Y., Hinchliffe, E., Adams, J.L., Silverstone, A.L., and Drake, R. (2005). Improving the nutritional value of Golden Rice through increased pro-vitamin A content. Nat. Biotechnol. 23 482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolillo, D.J.J., Garvin, D.F., and Parthasarathy, M.V. (2004). The chromoplasts of Or mutants of cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis). Protoplasma 224 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H., Kreunen, S.S., Cuttriss, A.J., DellaPenna, D., and Pogson, B.J. (2002). Identification of the carotenoid isomerase provides insight into carotenoid biosynthesis, prolamellar body formation, and photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 14 321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyke, K.A. (1997). The genetic control of plastid division in higher plants. Am. J. Bot. 84 1017–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani, S., Beyer, P., Lintig, J., Hugueney, P., and Kleinig, H. (1998). Induced β-carotene synthesis driven by triacylglycerol deposition in the unicellular alga Dunaliella bardawil. Plant Physiol. 116 1239–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralley, L., Enfissi, E.M.A., Misawa, N., Schuch, W., Bramley, P.M., and Fraser, P.D. (2004). Metabolic engineering of ketocarotenoid formation in higher plants. Plant J. 39 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, E.J., Pyke, K.A., and Leech, R.M. (1995). arc6, an extreme chloroplast division mutant of Arabidopsis also alters proplastid proliferation and morphology in shoot and root apices. J. Cell Sci. 108 2937–2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronen, G., Cohen, M., Zamir, D., and Hirschberg, J. (1999). Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis during tomato fruit development: Expression of the gene for lycopene epsilon-cyclase is down-regulated during ripening and is elevated in the mutant Delta. Plant J. 17 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann, G. (2002). Molecular evolution of carotenoid biosynthesis from bacteria to plants. Physiol. Plant. 116 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H., Tan, B.C., Gage, D.A., Zeevaart-Jan, A.D., and McCarty, D.R. (1997). Specific oxidative cleavage of carotenoids by VP14 of maize. Science 276 1872–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewmaker, C.K., Sheehy, J.A., Daley, M., Colburn, S., and Ke, D.Y. (1999). Seed-specific overexpression of phytoene synthase: Increase in carotenoids and other metabolic effects. Plant J. 20 401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin, A.J., Schwartz, S.H., Auldridge, M., Taylor, M.G., and Klee, H.J. (2004). The tomato carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 genes contribute to the formation of the flavor volatiles β-ionone, pseudoionone, and geranylacetone. Plant J. 40 882–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stålberg, K., Lindgren, O., Ek, B., and Höglund, A.S. (2003). Synthesis of ketocarotenoids in the seed of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 36 771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, A., Korszun, R., Hartl, F.U., and Flanagan, J. (1996). A zinc finger-like domain of the molecular chaperone DnaJ in involved in binding to denatured protein substrates. EMBO J. 15 408–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M., and Ramsay, G. (2005). Carotenoid biosynthesis in plant storage organs: Recent advances and prospects for improving plant food quality. Physiol. Plant. 124 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Steege, G., Nieboer, M., Swaving, J., and Tempelaar, M.J. (1992). Potato granule-bound starch synthase promoter-controlled GUS expression: Regulation of expression after transient and stable transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 20 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varagona, M.J., Purugganan, M., and Wessler, S.R. (1992). Alternative splicing induced by insertion of retrotransposons into the maize waxy gene. Plant Cell 4 811–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishnevetsky, M., Ovadis, M., Itzhaki, H., Levy, M., Libal, W.Y., Adam, Z., and Vainstein, A. (1996). Molecular cloning of a carotenoid-associated protein from Cucumis sativus corollas: Homologous genes involved in carotenoid sequestration in chromoplasts. Plant J. 10 1111–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishnevetsky, M., Ovadis, M., and Vainstein, A. (1999). Carotenoid sequestration in plants: The role of carotenoid-associated proteins. Trends Plant Sci. 4 232–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitha, S., Froehlich, J.E., Koksharova, O., Pyke, K.A., van Erp, H., and Osteryoung, K.W. (2003). ARC6 is a J-domain plastid division protein and an evolutionary descendant of the cyanobacterial cell division protein Ftn2. Plant Cell 15 1918–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Arnim, A.G., Deng, X.W., and Stacey, M.G. (1998). Cloning vectors for the expression of green fluorescent protein fusion proteins in transgenic plants. Gene 221 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lintig, J., Welsch, R., Bonk, M., Giuliano, G., Batschauer, A., and Kleinig, H. (1997). Light-dependent regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis occurs at the level of phytoene synthase expression and is mediated by phytochrome in Sinapis alba and Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant J. 12 625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Western, T.L., Skinner, D.J., and Haughn, G.W. (2000). Differentiation of mucilage secretory cells of the Arabidopsis seed coat. Plant Physiol. 122 345–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X., Al Babili, S., Kloti, A., Zhang, J., Lucca, P., Beyer, P., and Potrykus, I. (2000). Engineering the provitamin A (β-carotene) biosynthetic pathway into (carotenoid-free) rice endosperm. Science 287 303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.C., and Gassmann, W. (2003). RPS4-mediated disease resistance requires the combined presence of RPS4 transcripts with full-length and truncated open reading frames. Plant Cell 15 2333–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.