Abstract

The two oligonucleotide strands of a siRNA duplex are functionally asymmetric in assembling the RNAi effector, RNA-induced gene silencing complex (RISC). Based on this asymmetric RISC assembly model in vitro, formation of a microRNA (miRNA) and complementary miRNA (miRNA*) duplex was proposed to be an essential step for the assembly of miRNA-associated RISC (miRISC). We observed here that a strong structural bias exists in the selection of a mature miRNA strand for RISC assembly in zebrafish using an intronic miRNA-like vector to target EGFP mRNA for regulation. The position of the stemloop in a precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) was involved in the determination of miRNA–miRNA* asymmetry of the pre-miRNA stemarm, leading to different miRNA maturation during miRISC assembly. These findings suggest that the miRISC assembly is likely different from the RISC assembly model of siRNA in zebrafish, providing the first in vivo evidence for asymmetric miRISC assembly.

Keywords: microRNA (miRNA), RNA interference (RNAi), RNA-induced gene silencing complex (RISC), intron, zebrafish

Abbreviations: miRNA, microRNA; miRNA*, complementary micro-RNA; pre-miRNA, precursor of microRNA; pri-miRNA; primary precursor of miRNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; RNAi, RNA interference; RISC, RNA-induced gene silencing complex; Dicer, RNase III-familial endonuclease; Pol-II, RNA polymerase type II; mRNAm messenger RNA; pre-mRNA, precursor messenger RNA; RNP, ribonuclear particle; CMV, cytomegalovirus; SpRNAi, splicing-competent RNA intron; EGFP, green fluorescent protein; RGFP, red mutated fluorescent protein

1. Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) is a posttranscriptional gene silencing mechanism which can be triggered by double-stranded small interfering RNA (siRNA) or single-stranded miRNA in many eukaryotes. The functions of siRNA and miRNA are both mediated through RISC, a protein–RNA complex that directs either target gene transcript degradation or translational repression through the RNAi mechanism. Formation of siRNA duplexes has been found to play a key role in assembly of the siRNA-associated RISC (siRISC) (Cullen, 2004; Tomari and Zamore, 2005). Depending on the thermodynamic stability of both open ends of the double-stranded siRNA structure, the siRISC can be either symmetrically assembled to contain either one of the two strands or asymmetrically assembled (Schwarz et al., 2003; Tomari et al., 2004; Tang, 2005). The asymmetric assembly occurs when the two strands of a siRNA duplex are asymmetrically processed by Dicer, a member of the RNaseIII endonuclease family, resulting in preferential assembly for only one strand to carry out the RNAi activity while the other strand is degraded (Schwarz et al., 2003; Khvorova et al., 2003). Based on this siRNA programmed RISC assembly model, the formation of miRNA–miRNA* duplexes was thought to be an essential step for the assembly of miRNA-associated RISC (miRISC) even though this postulation was derived from in vitro siRNA experiments and computerized calculations. Thus, the presence of the miRNA–miRNA* duplex during RISC assembly remains to be elucidated.

The process of miRNA biogenesis in vertebrates presumably involves five steps. First, miRNA is generated as a long primary precursor miRNA (pri-miRNA) probably by RNA polymerases type II (Pol-II) (Lin et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004). Second, the long pri-miRNA is excised by either Drosha-like RNaseIII endonucleases and its related microprocessors or spliceosomal components to form precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) (Lee et al., 2003; Denli et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2003) and then, third, the pre-miRNA is exported out of the nucleus by Ran-GTP and a receptor Exportin-5 (Yi et al., 2003; Lund et al., 2004). Once in the cytoplasm, Dicer-like nucleases cleave the pre-miRNA to form mature miRNA. Lastly, the mature miRNA is incorporated into a ribonuclear particle (RNP) and together becomes the miRISC for executing RNAi-related gene silencing effects (Schwarz et al., 2003; Khvorova et al., 2003).

A recent review by Tang (2005), however, has proposed that the assembly processes between miRISC and siRISC are different. Unlike siRNA, Drosha and its related microprocessors were found to cleave intergenic pri-miRNA into pre-miRNA (Lee et al., 2003; Denli et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2004); nevertheless, their involvement in the final miRNA maturation and RISC assembly is not known yet. Further, Giraldez et al. (2005) have reported that the RNaseIII and dsRNA-binding domains of miRNA-associated Dicer were not required for loading into the RISC complex and subsequent gene silencing activity. Given that conventional miRISC theories were mainly based on the RISC assembly model of siRNA, the essential role of a siRNA-like duplex construct in miRISC assembly is therefore inconclusive. Conceivably, a careful step to distinguish the individual properties and differences between miRISC and siRISC assembly would facilitate our understanding of the evolutional and functional relationship between these two RNA-mediated gene-silencing pathways. We report here that a strong structural bias exists in the final step of miRNA maturation for miRISC assembly in zebrafish using an intronic miRNA-like vector to target EGFP mRNA for regulation, which suggests complex mechanisms for mi-RISC assembly.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Construction of miRNA expression systems

The miRNA-expressing SpRNAi-RGFP vectors were constructed as previously described (Lin et al., 2003). Synthetic oligonucleotides used for generation of miRNA–stemloop–miRNA* (❶) and miRNA*–stemloop–miRNA (❷) pre-miRNA inserts directed against the EGFP nts 280–302 sequences were 5′-GTCCGATCGT CAAGAAGATG GTGCGCTCCT GGATCAAGAG ATTCCAGGAG CGCACCATCT TCTTCGACGCGTCAT-3′ (❶ sense) and 5′-ATGACGCGTC GAAGAAGATG GTGCGCTCCT GGAATCTCTT GATCCAGGAG CGCACCATCT TCTT-GACGAT CGGAC-3′ (❶ antisense), and 5′-GTCCGATCGT CTCCAGGAGC GCACCATCTT CTTTCAAGAG ATAA-GAAGAT GGTGCGCTCC TGGACGACGC GTCAT-3′ (❷ sense) and 5′-ATGACGCGTC GTCCAGGAGC GCAC-CATCTT CTTATCTCTT GAAAGAAGAT GGTGCGCTCC TGGAGACGAT CGGAC-3′ (❷ antisense). Off-target pre-miRNAs were designed accordingly, but targeting against the gag region of HIV genome nts +1401 to +1423 (accession number NC001802). This region possesses neither homology nor complementarity to the target EGFP gene.

To test the requirement of a siRNA-like duplex construct in miRISC assembly, the above pre-miRNAs were designed to contain perfectly matched stemarm domains. Although most of the native pre-miRNAs contain mismatched area in their stemarms, it is not necessary for us to construct an imperfect paired stemarm in order to trigger RNAi-related gene silencing. Previous studies have demonstrated that a mature miRNA can be generated by placing a perfectly matched siRNA duplex in the miR-30 pre-miRNA structure (Lee et al., 2003; Boden et al., 2004). Further, there are many genes not subjected to the regulation of native miRNAs, in particular, EGFP, which can be otherwise silenced by intracellular transfection of the pre-miRNA containing a perfectly matched stemarm construct. Therefore, we define a mature miRNA based on its biogenetic function and mechanism, rather than the structural complementarity of its precursor. In this view, any small hairpin RNA can be a pre-miRNA if a mature miRNA is successfully processed from the small hairpin RNA and further assembled into miRISC for target gene silencing.

The pre-miRNA constructs so designed were inserted into the SpRNAi-RGFP gene cassette (Lin et al., 2003), respectively, for efficient expression. The insertion site was generated by Puv1/Mlu1 cleavage of the original SpRNAi-RGFP gene cassette in the vector and ligated with the hybridized duplex of each paired sequences, which has been digested by Puv1 and Mlu1. Because the pre-miRNA insert within the SpRNAi intron region is flanked with a PvuI and an MluI restriction site at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively, the primary insert can be easily removed and replaced by various gene-specific inserts (e.g. anti-EGFP) possessing cohesive ends. Concurrently, a 5′-splicing-defective SpRNAi-RGFP gene was constructed by AvaII cleavage and nuclease S1 degradation of the 5′-splice site in the SpRNAi-RGFP gene cassette. This truncated 5′-splice site was then closed by blunt-end ligation, resulting in an unrecognizable region to spliceosome. For cloning the recombinant SpRNAi-RGFP genes with correct sizes, the ligated nucleotide sequences (10 ng) were amplified by PCR with primers (5′-CTCGAGCATG GTGAGCGGCC TGCTGAA-3′ and 5′-TCTAGAAGTT GGCCTTCTCG GGCAGGT-3′) at 94 °C 1 min and 70 °C, 2 min for 25 cycles. The resulting PCR products were fractionated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and a ~900-bp pre-miRNA-inserted RGFP oligonucleotide was extracted and purified by gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for sequencing.

2.2. Liposomal transfection

Tg(UAS:gfp) strain zebrafishes were raised in a fish container with 10 ml of 0.2× serum-free RPMI 1640 medium during transfection. A transfection pre-mix was prepared by gently dissolving 6 μl of Fugene reagent (Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) in 1× serum-free RPMI 1640 medium. Plasmid vectors (20 μg) were then mixed with the pre-mix for 30 min and directly applied to the fish container with Tg(UAS:gfp). Total three dosages were given in a 12-h interval (total 60 μg plasmids). Samples were collected 60 h after the first transfection.

2.3. Northern blot analysis

The low stringency Northern blotting was performed as previously described (Lin et al., 2003). Zebrafish larvae were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then homogenized. Total RNAs from the fishes were isolated by either RNeasy columns (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol or ultracentrifugation in guanidinium-chloride solution. Each set of total RNAs (10 μg) was then fractionated by electrophoresis in 1% formaldehyde–agarose gel and transferred to nylon membranes. The antisense target RGFP-miRNA probes were synthesized by the Sigma-Genosys core labs (Woodlands, TX) and labeled with terminal transferase (20 U) tailing for 20 min in the presence of [32P]dATP (> 3000 Ci/mM, Amersham International, Arlington Heights, IL). Hybridization was carried out in a mixture of 50% freshly deionized formamide (pH 7.0), 5× Denhardt’s solution, 0.5% SDS, 4× SSPE and 250 μg/μL denatured salmon sperm DNAs (18 h, 42 °C). Membranes were sequentially washed twice in 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS (10 min, 25 °C), and once in 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS (30 min, 42 °C) before autoradiography.

2.4. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

Homogenized fishes were treated with the CelLytic-M lysis/extraction reagent (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with protease inhibitors, Leupeptin, TLCK, TAME and PMSF, as recommended by the manufacturer, and then were incubated at room temperature on a plate shaker for 15 min, scraped into microtubes and centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 × g to pellet cell debris. Protein-containing lysates were collected and stored at ×70 °C until use. Protein determinations were conducted as described (Lin et al., 2003), using the improved SOFTmax software package on an E-max microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Each 30 μg lysate was added to SDS-PAGE sample buffer under reducing (+50 mM DTT) and non-reducing (no DTT) conditions and boiled for 3 min before loading onto 6~8% polyacylamide gels; molecular weights were determined by comparison to standard proteins (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed according to the standard protocols. Proteins resolved by PAGE were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with Odyssey blocking reagent (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NB) for 1~2 h at room temperature. We assessed GFP expression using primary antibodies directed against EGFP (1:5000; JL-8) or RGFP (1:10,000; BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA) by overnight incubation at 4 °C. The immunoblot was then rinsed 3 times with TBS-T and exposed to goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated secondary antibody to Alexa Fluor 680 reactive dye (1:2000; Molecular Probes) for 1 h at the room temperature. After three additional TBS-T rinses, fluorescent scanning of the immunoblot and image analysis was conducted using Li-Cor Odyssey Infrared Imager and Odyssey Software v.10 (Li-Cor).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Stemloop-associated miRNA maturation in zebrafish

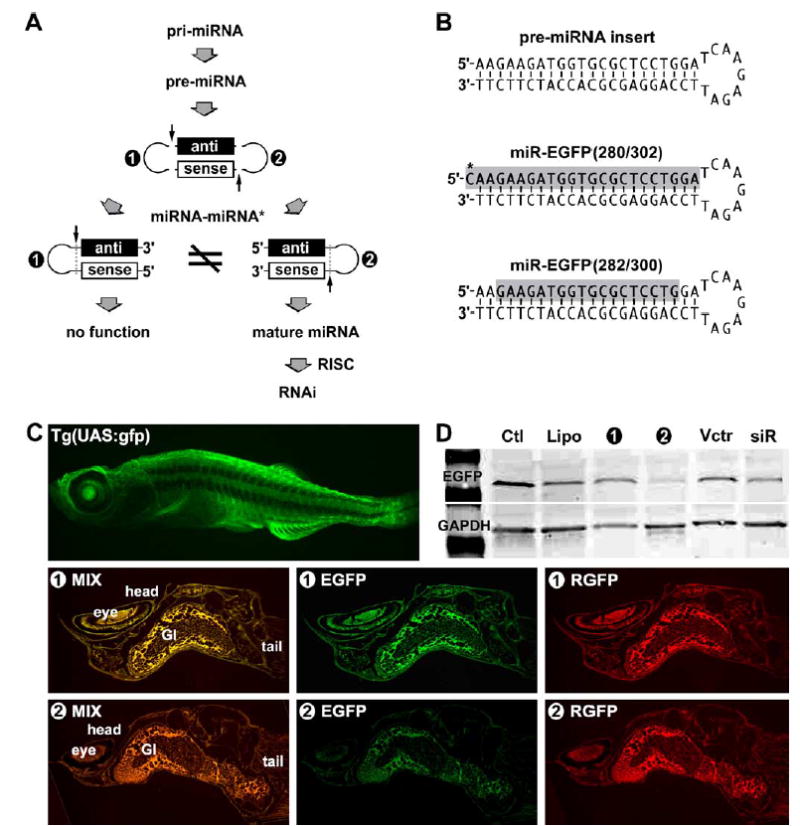

We introduced hairpin-like pre-miRNAs into two-week-old zebrafish larvae and successfully tested the processing and functional significance of different miRNA–miRNA* structures using an intronic miRNA expression system described previously (Lin et al., 2003; Lin and Ying, 2004a,b). The pre-miRNA expression was driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, which has been previously established as a viable approach for manipulation of mRNA expression in zebrafish (Verri et al., 1997). Based on conventional reasoning, the stemloop structure located in either end of the miRNA–miRNA* duplex should be equally cleaved by Dicer in order to form siRNA; therefore, functional bias would not be observed in the stemloop. However, we observed different gene-silencing responses unexpectedly when the transfection results from a pair of symmetric hairpin constructs between 5′-miRNA*–stem-loop–miRNA-3′ and 5′-miRNA–stemloop–miRNA*-3′ pre-miRNAs were compared; both contained the same perfectly matched siRNA-like duplex stemarm (shown as ❶ and ❷, respectively in Fig. 1A). Different mature miRNAs were identified from the transfections of the pre-miRNAs, suggesting that the stemloop structures of these pre-miRNAs can affect Dicer recognition and result in different asymmetry of the siRNA-like stemarm construct. This type of asymmetry leads to strand selection of the mature miRNA for effective RISC assembly.

Fig. 1.

Bias of miRNA–miRNA* asymmetry in RISC in vivo. Different preferences of RISC assembly were observed by transfection of 5′-miRNA*–stemloop–miRNA-3′ (❶) and 5′-miRNA–stemloop–miRNA*-3′ (❷) pre-miRNA constructs in zebrafish, respectively. (A) Based on the assembly rule of siRNA RISC, the processing of both ❶ and ❷ should result in the same siRNA duplex for RISC assembly; however, the experiments demonstrate that only the ❷ construct was used in RISC assembly. Because the miRNA is predicted to be complementary to its target messenger RNA, the “antisense” (black bar) refers to the miRNA and the “sense” (white bar) refers to its complementarity, miRNA*. (B) Two designed mature miRNA identities were found only in the ❷-transfected zebrafishes, namely miR-EGFP(280/302) and miR-EGFP(282/300). (C) In vivo gene silencing efficacy was only observed in the transfection of the ❷ pre-miRNA construct, but not the ❶ construct. Since the color mixture of EGFP and RGFP displayed more red than green (as shown in deep orange), the expression level of target EGFP (green) was significantly reduced, while miRNA indicator RGFP (red) was evenly present in all vector transfections. A strong strand selection was observed in favor of the 5′-stemloop strand of the designed pre-miRNAs in RISC. (D) Western blot analysis of protein expression levels confirmed the specific EGFP silencing result of (C). No detectable gene silencing was observed in fishes without (Ctl) and with liposome only (Lipo) treatments. The transfection of either a U6-driven siRNA vector (siR) or an empty vector (Vctr) without the designed pre-miRNA insert resulted in no gene silencing significance.

To determine the structural preference of the hairpin pre-miRNAs, we have isolated the small RNAs in zebrafish using mirVana miRNA isolation columns (Ambion, Austin, TX) and then precipitated all potential miRNAs complementary to the target EGFP region using latex beads containing the target RNA sequence. The designed pre-miRNA constructs were directed against the target green fluorescent protein (EGFP) mRNA sequence nucleotides 280–302 in the Tg(UAS:gfp) strain zebrafish, of which the EGFP expression was constitutively driven by the β-actin promoter in almost all cell types. As shown in the Fig. 1B, two major miRNA identities were verified to be active (gray-shading sequences). Because of the fast turn-over rate of small RNAs in vivo (Tourriere et al., 2002; Wilusz and Wilusz, 2004), the shorter miR-EGFP(282/300) is likely to be a stably degraded form of the miR-EGFP(280–302). The first 5′-cytosine (labeled by an asterisk, *) of the miR-EGFP(280–302) was not included in the designed target region and probably provided by the original intron sequence because the cytosine (C*) is the most adjacent nucleotide to the 5′-end of the designed pre-miRNA structure in the intron. Due to the fact that the effective miR-EGFP(280–302) miRNA was detected only in the zebrafish transfected by the 5′-miRNA – stemloop –miRNA*-3′ construct (❷), the stemloop of the construct ❷ rather than the construct ❶ pre-miRNA is able to determine the right anti-sense EGFP domain for miRISC assembly. Given that Dicer cleavage resulted in distinct mature miRNAs from both pre-miRNA constructs (Fig. 3), switching the pre-miRNA stemloop did not affect the normal process of miRNA maturation; however, the resulting mature miRNAs were different in orientation. One possibility for this preference is that the structure and/or sequence of the stemloop preferably facilitate miRNA maturation from one orientation than the other. Alternatively, the stemloop may change the Dicer recognition and thus generates differently asymmetric profiles to the pre-miRNA stemarm. In either way, the stemloop provides a structural and functional bias to the miRNA selection during miRISC assembly.

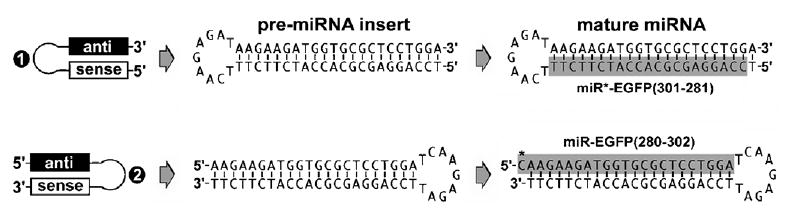

Fig. 3.

Bias of miRNA–miRNA* asymmetry in miRISC in vivo. Different preferences of RISC assembly were observed in the transfections of 5′-miRNA*–stemloop–miRNA-3′ (❶) and 5′-miRNA–stemloop–miRNA*-3′ (❷) pre-miRNA constructs in zebrafish, respectively. Based on the assembly rule of siRISC, the processing of both ❶ and ❷ pre-miRNAs should result in the same siRNA duplex for RISC assembly; however, the present experiments demonstrate that only the ❷construct was able to silence target EGFP. An effective mature miRNA, namely miR-EGFP(280/302), was detected in the ❷-transfected zebrafishes directed against target EGFP, whereas transfection of the ❶construct produced a different mature miRNA, miR*-EGFR(301–281), which was partially complementary to the miR-EGFP(280/302) and possessed no gene silencing effects on EGFP expression.

3.2. In vivo gene silencing triggered by asymmetric miRNA maturation

The effectiveness of miRNA-induced gene silencing differs between the construct ❶ and ❷ pre-miRNA transfections in various fish organs. Fig. 1C shows that transfection of the miRNA-expressing vector into the Tg(UAS:gfp) zebrafish co-expressed a red mutated fluorescent protein (RGFP), serving as a positive indicator for the miRNA generation in the transfected cells. This approach has been successfully used in several mouse and human cell lines to show the RNAi effects (Lin et al., 2003; Lin and Ying, 2004b). We applied the liposome-capsulated vector (total 60 μg) to the fishes and found that the vector easily penetrated almost all tissues of the two-week-old zebrafish larvae within 24 h. The co-expression (red) of indicator RGFP and designed pre-miRNA was detected in both of the fishes transfected by either 5′-miRNA* – stemloop –miRNA-3′ or 5′-miRNA – stemloop – miRNA*-3′ pre-miRNA, whereas the silencing of target EGFP expression (green) was observed only in the fish transfected by the 5′-miRNA–stemloop–miRNA*-3′ (❷) pre-miRNA (Fig. 1C and D). The suppression level in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract was found to be less effective, probably due to the high RNase activity in this region. Because switching the stemloop position has changed the 5′-end thermostability of the siRNA-like stemarm, resulting in different miRNA maturation patterns, we suggest that the stemloop of a pre-miRNA may be involved in Dicer recognition and strand selection of a mature miRNA for effective RISC assembly and the following gene silencing.

The stemloop-associated miRNA–miRNA* asymmetry in RISC assembly poses a critical parameter, which is missing in current computer programs, for miRNA prediction. When applying our observation in comparison with all other currently known structures of intronic pre-miRNAs in vertebrates, e.g. miR-26a-1, miR-26a-2, miR-26b, miR-28, miR-30c-1, miR-30e and miR-33, we have found that their mature miRNAs are preferentially located in one stemarm of the pre-miRNAs, whereas the intronic miRNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster can be present in either 5′- or 3′-stemarm, or both. The data suggests that the expression patterns of these intronic miRNAs are not well conserved between vertebrates and invertebrates. Given that the cleavage site of Dicer in the pre-miRNA stemarm determines the strand selection of a mature miRNA (Lee et al., 2003), the stemloop likely functions as a determinant for the recognition of a special cleavage site. Unlike the dual open-ends of siRNA, a hairpin-like pre-miRNA structure has the advantage of using its stemloop structure to control the asymmetry of miRNA maturation for more efficient RISC assembly. This structural preference may be caused by distinct assembly properties between miRISC and siRISC in terms of the evolution of the RNAi mechanism. Thus, studies of the stemloop varieties will improve our understanding of the mechanism by which miRISC is assembled.

3.3. Essential roles of pre-miRNA stemloop and RNA splicing in miRNA maturation

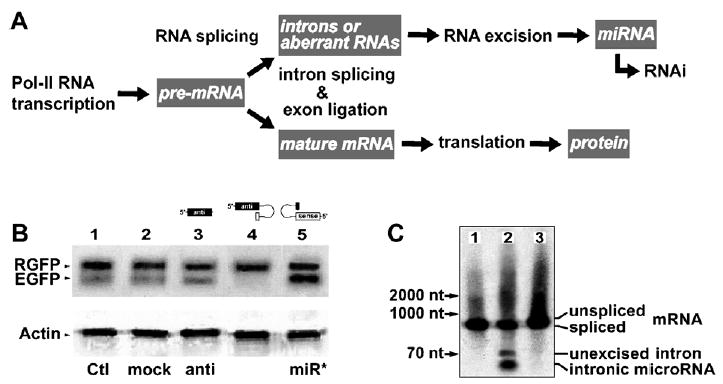

Intronic miRNA is a new class of small single-stranded regulatory RNAs derived from the processing of pre-mRNA introns (Fig. 2A). It is similar to previously described intergenic miRNAs structurally and functionally but differs in its unique requirement of Pol-II and RNA splicing components for biogenesis (Lin et al., 2003; Ying and Lin, 2004). Single-stranded siRNA can be assembled into RISCs (Martinez et al., 2002), whereas mature intronic miRNA containing no pre-miRNA stemloop structure may not be efficiently assembled into the miRISC in vivo. Fig. 2B showed the specific gene silencing efficacy of the miR-EGFP(280–302)–stemloop transfection in the Tg(UAS:gfp) fish larvae. The stemloop structure was maintained by a hexamer oligonucleotide pairing to the 3′ proximity of the mature miRNA stemarm. The EGFP expression was decreased over 85% as determined by Western blot analysis, whereas no silencing effect was observed in the transfections of miR-off target-stemloop, miR-EGFP(280–302) without the stemloop and miR*–EGFP(302–208)–stem-loop constructs. The expressions of control RGFP and house-keeping actin were not affected in all transfections. If a strict 20~22 base-paired siRNA construct was required for miRISC assembly, no mature miRNA would be generated for silencing the target EGFP in Fig. 2B and also the mature miRNAs derived from both ❶ and ❷ pre-miRNA constructs in Fig. 1 should be the same. Furthermore, single-stranded RNA with proper 5′-phosphorylation has recently been found in functional RISC assembly (Martinez et al., 2002; Schwarz et al., 2003). These results not only demonstrate the functional role of a pre-miRNA stemloop in miRISC assembly but also indicate that no strict siRNA duplex construct is required for loading into the miRISC complex.

Fig. 2.

Biogenesis and function of intronic miRNAs. (A) The intronic miRNA is co-transcribed with a precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) by Pol-II and cleaved out of the pre-mRNA by an RNA splicing machinery, spliceosome. The spliced intron is further processed into mature miRNAs capable of triggering RNAi effects, while the ligated exons become a mature messenger RNA (mRNA) for protein synthesis. (B) When a designed miR-EGFP(280–302)–stemloop RNA construct was introduced into the Tg(UAS:gfp) fishes, we detected a strong and specific RNAi effect only on the target EGFP (lane 4). No detectable gene silencing effect was observed in other lanes from left to right: 1, blank EGFP/RGFP control (Ctl); 2, miRNA–stemloop targeting HIV-p24 (mock); and 3, miRNA without stemloop (anti); and 5, stemloop–miRNA* complementary to the miR-EGFP(280–302) sequence (miR*). (C) Three different miR-EGFP(280–302) expression systems were designed for miRNA biogenesis from left to right: 1, vector expressing intron-free RGFP, no pre-miRNA insert; 2, vector expressing RGFP with an intronic 5′ -miRNA–stemloop–miRNA*-3′ insert; and 3, vector similar to the 2 construct but with a defected 5′ -splice site in the intron. In Northern bolt analysis probing the miR-EGFP(280–302) sequence, mature miRNA was released only from the spliced intron resulted from the vector 2 construct in the cell cytoplasm.

On the other hand, we have introduced differently designed miRNA expression systems into the fish larvae, the identity of mature miR-EGFP(280–302) only resulted from a spliced intron, but not the unspliced pre-mRNA that contained a defected intron (Fig. 2C), suggesting the necessity of RNA splicing. Therefore, we have shown for the first time that artificial miRNAs are able to induce effective RNAi phenomena in zebrafish, using the miRNA biogenesis system described above. These findings also suggest an evolutionary preservation of the mechanism by which the miRNAs are derived from introns in vivo and capable of fine-tuning target gene expression. Indeed, this model system provides a valuable tool for genetic and miRNA-associated research in vivo.

3.4. Discussion

Although some of currently identified miRNAs are encoded in the genomic intron region of a gene but in the opposite orientation to its gene transcript, they are not considered as intronic miRNAs because they do not share the same promoter with the gene and also they do not need to be released from the gene transcript by RNA splicing. For the transcription of these miRNAs, their promoter should be located in the antisense direction to the gene, making the gene a potential target for these antisense miRNAs. A good example is let-7c, which was found to be an intergenic miRNA located in the antisense region of the intron of a gene. Therefore, the current computer programs designed for miRNA prediction usually include these intergenic miRNAs but not the intronic miRNAs. Because the intronic miRNAs are encoded in the gene transcript precursors (pre-mRNAs) and share the same promoter with the encoded gene transcripts, they were treated as protein-coding regions and were excluded from the conventional miRNA prediction. Thus, a miRNA prediction program including database of non-coding sequences in the protein-coding regions is needed for thoroughly screening the intronic pre-miRNAs in the genomes.

To date, more than 135 miRNAs have been identified to be highly conserved between mammals and fishes (John et al., 2004). This may be an underestimate since the information on unknown 3′-UTR sequences in both genomes, non-UTR targets in the internal regions of gene transcripts, and new ortholog annotation such as intronic miRNAs were not considered. Approximately 10~30% of a spliced intron are exported into cytoplasm with a moderate half-life (Clement et al., 1999). Several types of intronic miRNA have been identified in C. elegans, mouse and human genomes (Ambros et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2003; Rodriguez et al., 2004). Therefore, it is understandable that the current miRNA computing programs do not predict fully the potential miRNA-like molecules. The finding of in vivo bias in miRNA–miRNA* asymmetry (Fig. 3) has opened new avenues for predicting miRNA varieties. Although there may be more than one type of new miRNAs to be identified and many new parameters to be generated from different miRNAs, the similarities and differences among these different types of miRNAs will provide better understanding of the small regulatory RNA world. Indeed, a broader definition for various miRNAs is needed.

Acknowledgments

The Tg(UAS:gfp) zebrafish line was acquired from the Zebrafish International Resource Center supported by grant #RR12546 from the NIH-NCRR. This study was supported by NIH/NCI grant CA-85722.

References

- Ambros V, Lee RC, Lavanway A, Williams PT, Jewell D. MicroRNAs and other tiny endogenous RNAs in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2003;13:807–818. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden D, Pusch O, Silbermann R, Lee F, Tucker L, Ramratnam B. Enhanced gene silencing of HIV-1 specific siRNA using microRNA designed hairpins. Nucleic Acid Res. 2004;32:1154–1158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement JQ, Qian L, Kaplinsky N, Wilkinson MF. The stability and fate of a spliced intron from vertebrate cells. RNA. 1999;5:206–220. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR. Derivation and function of small interfering RNAs and microRNAs. Virus Res. 2004;102:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denli AM, Tops BBJ, Plasterk RHA, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Processing of primary microRNAs by the microprocessor complex. Nature. 2004;432:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature03049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez AJ, et al. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science. 2005;308:833–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1109020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, et al. The microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature03120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human microRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvorova A, Reynolds A, Jayasena SD. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, et al. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SL, Chang D, Wu DY, Ying SY. A novel RNA splicing-mediated gene silencing mechanism potential for genome evolution. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:754–760. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SL, Ying SY. Combinational therapy for HIV-1 eradication and vaccination. Int J Oncol. 2004a;24:81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SL, Ying SY. Novel RNAi therapy—intron-derived micro-RNA drugs. Drug Des Rev. 2004b;1:247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J, Patkaniowska A, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R, Tuschl T. Single-stranded antisense siRNAs guide target RNA cleavage in RNAi. Cell. 2002;110:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00908-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Griffiths-Jones S, Ashurst JL, Bradley A. Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res. 2004;14:1902–1910. doi: 10.1101/gr.2722704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz DS, Hutvagner G, Du T, Xu Z, Aronin N, Zamore PD. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell. 2003;115:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G. siRNA and miRNA: an insight into RISCs. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomari Y, Matranga C, Haley B, Martinez N, Zamore PD. A protein sensor for siRNA asymmetry. Science. 2004;306:1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.1102755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomari Y, Zamore PD. Perspective: machines for RNAi. Genes Dev. 2005;19:517–529. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourriere H, Chebli K, Tazi J. mRNA degradation machines in eukaryotic cells. Biochimie. 2002;84:821–837. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01445-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verri T, et al. The bacteriophage T7 binary system activates transient transgene expression in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:492–495. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilusz CJ, Wilusz J. Bringing the role of mRNA decay in the control of gene expression into focus. Trends Genet. 2004;20:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3011–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying SY, Lin SL. Intron-derived microRNAs—fine tuning of gene functions. Gene. 2004;342:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]