What is endometriosis?

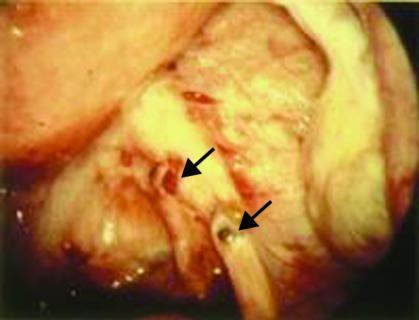

Endometriosis is a chronic condition characterised by growth of endometrial tissue in sites other than the uterine cavity, most commonly in the pelvic cavity, including the ovaries, the uterosacral ligaments, and pouch of Douglas (fig 1). Common symptoms include dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, non-cyclic pelvic pain, and subfertility (table 1). The clinical presentation is variable, with some women experiencing several severe symptoms and others having no symptoms at all. The prevalence in women without symptoms is 2-50%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used and the populations studied.1 The incidence is 40-60% in women with dysmenorrhoea and 20-30% in women with subfertility.w1-w3 The severity of symptoms and the probability of diagnosis increase with age.w4 The most common age of diagnosis is reported as around 40, although this figure came from a study in a cohort of women attending a family planning clinic.w5 Symptoms and laparoscopic appearance do not always correlate.2 The American Society for Reproductive Medicine has published a classification of severity of endometriosis at laparoscopy.w6

Fig 1 Mild pelvic endometriosis seen at the time of diagnostic laparoscopy. Arrows show typical endometriotic deposits (reproduced with permission from Dr D A Hill)

Table 1.

Common presentations of endometriosis

| Symptom | Alternative diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Recurrent painful periods | Adenomyosis, physiological |

| Painful intercourse | Psychosexual problems, vaginal atrophy |

| Painful micturition | Cystitis |

| Painful defecation during menstruation | Constipation, anal fissures |

| Chronic lower abdominal pain | Irritable bowel syndrome, neuropathic pain, adhesions |

| Chronic lower back pain | Musculoskeletal strain |

| Adnexal masses | Benign and malignant ovarian cysts, hydrosalpinges |

| Infertility | Unexplained (assuming normal ovulation and semen parameters with patent tubes) |

Summary points

Medical treatment

Avoid prescribing medical treatment for women who are trying to conceive

The simpler treatments—such as the combined oral contraceptive pill, oral or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and the levonorgestrel intrauterine system—are as effective as the gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues and can be used long term

Surgical treatment

Laparoscopic excision or ablation at time of diagnostic laparoscopy if possible

Endometriomata (large cysts of endometriosis) are best stripped out instead of drainage and ablation

Recurrences

In the five years after surgery or medical treatment 20-50% of women will have a recurrence

Long term medical treatment (with or without surgery) has the potential to reduce recurrence but evidence based research is lacking

What are the causes of endometriosis?

Several factors are thought to be involved in the development of endometriosis. Retrograde menstruation remains the dominant theory for the development of pelvic endometriosis, though as this is almost universal it is unlikely to be the sole explanation.w7-w9 The quantity and quality of endometrial cells, failure of immunological mechanisms, angiogenesis, and the production of antibodies against endometrial cells may also have a role.w10 w11 Embryonic cells may give rise to deposits in distant sites such as the umbilicus, the pleural cavity, and even the brain.w8 w9

What are the risk factors for endometriosis?

Risk factors generally relate to exposure to menstruation: early menarche and late menopause increase the risk whereas the use of oral contraceptives reduces.w5

What is the natural course of endometriosis?

Studying the natural course is difficult because of the need for repeat laparoscopy. Two studies in which laparoscopy was repeated after treatment in women given placebo, however, reported that over 6-12 months, endometrial deposits resolved spontaneously in up to a third of women, deteriorated in nearly half, and were unchanged in the remainder.w12 w13

Diagnosis of endometriosis

What features of history and examination are important?

In women of reproductive age who present with recurrent dysmenorrhoea or pelvic pain you should take a full history of reproduction and carry out a pelvic examination. The cyclical nature of the pain and the relation of the pain to menstruation points to the diagnosis of endometriosis. Painful micturition, defecation, and dyspareunia are also associated. In young women you should consider other diagnoses such as pelvic infection, problems in early pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cyst torsion, and appendicitis (table 1). During pelvic examination, tenderness in the posterior fornix or adnexa, nodules in the posterior fornix, or adnexal masses may indicate endometriosis. Adolescents presenting with dysmenorrhoea do not require a pelvic examination as disease is uncommon.

How is endometriosis diagnosed?

Transvaginal ultrasonography can reliably detect endometriomata (cysts of endometriosis), but failure to reveal cystic structures does not exclude the diagnosis of endometriosis.3 w14 Magnetic resonance imaging is increasingly used to identify subperitoneal deposits, although retroversion, endometriomata, and bowel structures may mask small nodules.4 w15

Although concentrations of the cancer antigen CA125 are slightly raised in some women with endometriosis, the test neither excludes nor diagnoses endometriosis and is not considered useful in establishing the diagnosis.5 The threshold for surgery is unlikely to be influenced by the CA125 concentration, and the guidelines from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists described CA125 as having only limited value as either a screening or a diagnostic test.6

Laparoscopy is the only diagnostic test that can reliably rule out endometriosis. It is also accurate in detecting endometriosis and is considered the standard investigation.6

What are the indications for laparoscopy?

Many young women experience dysmenorrhoea (about 60-70%), and unless there are other features to indicate endometriosis laparoscopy is not recommended.w16 Some women will require further investigation to guide management. For adolescents who present with dysmenorrhoea, the recommended approach is to first prescribe non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and oral contraceptives.w17 w18 The lack of measurable pain relief with these drugs is usually an indication for further investigation.w19 Other indications for laparoscopy include severe pain over several months, pain requiring systemic therapy, pain resulting in days off work or school, or pain requiring admission to hospital.

What are the effective medical treatments?

Treatment options for medical therapy include oral contraceptives, progestogens, androgenic agents, and gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. All suppress ovarian activity and menses and atrophy of endometriotic implants, although the extent to which they achieve this varies. There have been few randomised controlled trials of medical treatment versus placebo, although many trials have compared different types of medical treatment.7 8 9 10 All medical treatments are similarly effective in relieving pain during treatment (table 2).

Table 2.

Medical treatment* for endometriosis

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Length of treatment recommended | Adverse events | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate/progestagens | Ovarian suppression | Long term | Weight gain, bloating, acne, irregular bleeding | May be given orally or by intramuscular or subcutaneous depot injection |

| Danazol | Ovarian suppression | 6-9 months | Weight gain, bloating, acne, hirsutism, skin rashes | Adverse effects on lipid profiles |

| Oral contraceptive | Ovarian suppression | Long term | Nausea, headaches | Can be used to avoid menstruation by skipping the placebo pills |

| GnRH analogue | Ovarian suppression by competitive inhibitor of GnRH analogue | 6 months | Hot flushes, other symptoms of hypo-oestrogenism | By injection or nasal spray only |

| Levonorgestrel intrauterine system | Endometrial suppression; ovarian suppression in some women | Long term use but change every 5 years in women <40 years | Irregular bleeding | Also reduces menstrual blood loss |

GnRH=gonadotrophin releasing hormone.

*Decisions about medical therapy will depend on patient's choice, available resources, plans for fertility, and ongoing symptoms. Side effect profile may influence choice.

The side effect profiles are important in deciding treatment choices. Progestogens are associated with irregular menstrual bleeding, weight gain, mood swings, and decreased libido. The side effects associated with danazol include skin changes, weight gain, and occasionally deepening of the voice, and it is infrequently prescribed now. GnRH analogues dramatically lower oestrogen concentrations, and side effects include the development of menopausal symptoms and the loss of bone mineral density with long term use (both reversible). Oestrogen therapy in an add back regimen is useful for preventing side effects with GnRH analogues.10 In the randomised controlled trials comparing subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (SC-DMPA) with GnRH analogues the bone loss was less with the progesterone during treatment.w20 w21

Recurrence of painful symptoms after six months of medical treatment may be as high as 50% in the 12-24 months after the treatment is stopped.w22 w23 Recurrence may in part be because large lesions respond poorly to medical treatment. It is generally accepted that endometriomata are not amenable to medical treatment, although temporary clinical relief may be achieved.

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is an established treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding but can also be used for dysmenorrhoea and endometriosis.11 w24 In one study only 10% of women who had a levonorgestrel intrauterine system after surgery for endometriosis had moderate or severe dysmenorrhoea compared with 45% of the women who had surgery only.12 In a trial of 82 women with endometriosis the levonorgestrel intrauterine system had similar effectiveness to GnRH analogues, but the potential for long term use of this system is advantageous if the woman does not want to conceive.13 It has also been used in women with rectovaginal disease.14 In the future aromatase inhibitors may have a therapeutic role in endometriosis as they inhibit oestrogen production selectively in endometriotic lesions, without affecting ovarian function.w25

Is surgery or medical treatment more effective?

There are no randomised controlled trials comparing medical versus surgical treatments for the management of endometriosis, and the decision about medical or surgical treatment at the time of diagnosis will depend on several factors including patient's choice, the availability of laparoscopic surgery, the desire for fertility, and concerns about long term medical therapy.

What are the effective surgical strategies?

Surgery for endometriosis can be performed laparoscopically or as an open procedure. It entails excision or ablation (by laser or diathermy), or both, of the endometriotic tissue with or without adhesiolysis. There are few trials of laparoscopic treatment.14 15 Surgical excision of endometriosis results in improved pain relief and improved quality of life after six months compared with diagnostic laparoscopy only.14 In one of the trials laparoscopic treatment also included uterine nerve ablation (LUNA),15 and pain improvement persisted for up to five years in more than half of the women.w26 About 20% of women do not report any improvement after surgery.14

No randomised controlled trials have compared laser versus electrosurgical removal of endometriosis, and only one small trial, with inconclusive results, compared excision versus ablation.w27

How often does endometriosis recur after surgery?

Recurrence of endometriosis after laparoscopic surgery is common.16 w26 Even with experienced laparoscopic surgeons, the cumulative rate of recurrence after five years is nearly 20%.17 Another study reported recurrence of dysmenorrhoea in almost a third of women within one year of laparoscopic surgery in women who received no other treatment.16

What is the role of uterine nerve ablation at the time of laparoscopy?

Randomised controlled trials of laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation at the time of laparoscopic excision of endometriosis compared with laparoscopic excision only showed no evidence of benefit, although there was limited evidence of benefit with presacral neurectomy.18

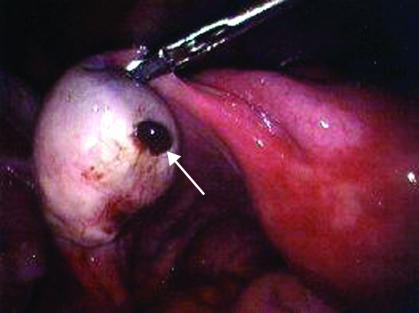

What is the evidence for surgery in women with endometriomata?

Randomised controlled trials comparing excision or drainage and ablation for endometriomata ≥3 cm reported that recurrences were reduced and subsequent spontaneous pregnancy increased in the women who underwent excision.19 Though excisional surgery of the capsule could lead to removal of normal ovarian tissue and result in reduced ovarian reserve,20 w28 there is no evidence that this occurs, whereas a recurrence of the endometriomata will inevitably mean further surgery.19

Fig 2 Laparoscopy of an enlarged ovary containing an endometriotic cyst leaking “chocolate” fluid (arrow) (reproduced with permission from Professor Peter Braude)

What is the best approach in women with rectovaginal disease?

Rectovaginal endometriosis presents surgical challenges because of difficult access and the possibility of injury to the bowel. Although reported long term outcomes are encouraging with advanced laparoscopic techniques, there are few prospective studies and no randomised controlled trials.16 17 One small study of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system in women with rectovaginal endometriosis found improved dysmenorrhoea, pelvic pain, and dyspareunia after one year.w29 A trial comparing oestrogen and progesterone combination with low dose progestogen in 90 women with rectovaginal disease reported substantial reductions at 12 months in all types of pain without major differences between groups.21 Overall, two thirds of patients were satisfied with this approach.

Should women have hormonal treatment before surgery for endometriosis?

Only one study has examined this question. There was no evidence of a difference in the difficulty of surgery in the women who had received preoperative hormonal treatment.w30

Should women have hormonal treatment after conservative surgery?

There was no evidence of improved pain relief with postoperative hormonal treatment (including danazol, GnRH analogues, oral contraceptives, and medroxyprogesterone acetate) up to 24 months after surgery.11 The studies to date are small, however, and there is insufficient follow-up to rule out a benefit.

What are the effects of hormonal treatment after oophorectomy (with or without hysterectomy)?

There was no evidence of increased rates of recurrence in women who had both ovaries removed and who were given nearly four years of combined hormone therapy, but the study was underpowered to detect clinically important differences.22

What is the impact of endometriosis on fertility?

Although management of pain may be the more immediate issue, the long term outcome of fertility should not be overlooked. Few studies have examined this. A systematic review of medical treatment for women with infertility and endometriosis did not find evidence of benefit,7 and it is not recommended for women trying to conceive.6 23 A systematic review of laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in women with subfertility suggested an improvement in pregnancy rate in the 9-12 months after surgery.w31 A second systematic review of laparoscopic excision compared with ablation endometriomata reported a fivefold increase in rate of pregnancy.19 There is the ongoing concern about ovarian reserve in women who have laparoscopic excision.20 w28 The other concern is the impact of endometriomata on artificial reproductive techniques.w32 The European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) recommends surgery if endometriomata are ≥4 cm.23

Conclusion

Endometriosis should be suspected in any woman of reproductive age who presents with dysmenorrhoea or chronic pelvic pain. Only laparoscopy can reliably identify endometriosis. If endometriosis is diagnosed at the time of laparoscopy, laparoscopic surgery should be the first choice of treatment, especially in women of reproductive age with an endometriomata. In women with endometriomata, the cyst wall should be stripped out, instead of drainage and ablation, as the recurrences are fewer and pregnancy rates improved. At present, there is no evidence of benefit of postoperative medical treatment but the levonorgestrel intrauterine system has the potential for long term use. In women who wish to conceive surgical, rather than medical, treatment should be offered.

Sources and selection criteria

I searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from the Cochrane Library (issue 3, 2006), Medline (1966 to April 2006), and citation lists of relevant publications and included randomised controlled trials and review articles. I used the following subject headings and keywords: endometriosis, menstr$ pain, period pain, and pelvic pain. I did not look for non-randomised studies except for studies on diagnostic tests and prevalence or if I found no randomised controlled trials.

Unanswered clinical questions

Is medical or surgical treatment more effective?

Does dysmenorrhoea in the adolescent years increase the risk of endometriosis later?

Does long term use of the combined oral contraceptive, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and the levonorgestrel intrauterine system reduce the recurrence of endometriosis?

What is the benefit of laparoscopic surgery for rectovaginal disease?

Additional educational resources

Resources for healthcare professionals

Clinical Evidence (www.clinicalevidence.org/ceweb/conditions/index.jsp) and Best Treatments (for patients) (www.besttreatments.co.uk/btuk/home.html)

Green Top Guideline on the investigation and management of endometriosis, produced by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (www.rcog.org.uk/resources/Public/pdf/endometriosis_gt_24_2006.pdf)

Guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, produced by the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (www.nvog.nl/files/rl_33_diagnostiek_en_behandeling_endometriose_eshre_web.pdf)

Consensus statement for the management of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis, produced by a group of US gynaecologists (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12413979&dopt=Abstract)

European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology Endometriosis Guidelines published 2006 (www.endometriosis.org/guidelines)

Information resources for patients

Patient UK information on endometriosis (www.patient.co.uk/showdoc/23068733)

Best Treatments information on endometriosis (www.besttreatments.co.uk/btuk/conditions/13729.jsp)

National Endometriosis Society (www.endo.org.uk)

Endometriosis SHE Trust, UK (www.shetrust.org.uk)

Kennedy S. Patient's essential guide to endometriosis. UK Guide (www.endometriosisguide.com)

Endoaware. The Online Endometriosis Support Community (www.endoaware.co.uk)

Molloy A. Endometriosis: a New Zealand guide. Auckland, NZ: Random House, 2006.

Tips for the general practitioner

Suspecting endometriosis

Pain before or during menstruation

Poor response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and combined contraceptive pill

Days off school or work

Dyspareunia

Recommended initial investigations

Transvaginal ultrasound to detect endometriomata

Not recommended as initial investigations

CA125 levels

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT)

Refer patient with suspected endometriosis if

Failed treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea with contraceptive pill and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Severe pain requiring systemic medication, days off school or work

Recurrence of symptoms in women with previously treated endometriosis

Delayed fertility in association with endometriosis

References

- 1.Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Human Reprod Update 2005;11:595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vercellini P, Trespidi L, De Giorgi O, Cortesi I, Parazzini F, Crosignani GP. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: relation to disease stage and localization. Fertil Steril 1996;65:299-304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alcazar JL, Laparte C, Jurado M, Lopez-Garcia G. The role of transvaginal ultrasonography combined with color velocity imaging and pulsed Doppler in the diagnosis of endometrioma. Fertil Steril 1997;67:487-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinkel K, Brosens J, Brosens I. Preoperative investigations. In: Sutton C, Jones K, Adamson D, eds. Modern management of endometriosis. Basingstoke: Taylor & Francis, 2006:71-85.

- 5.Mol BW, Bayram N, Lijmer JG, Wiegerinck MA, Bongers MY, van der Veen F, et al. The performance of CA-125 measurement in the detection of endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 1998;70:1101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The investigation and management of endometriosis. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2006. (Green Top Guideline No 24.) www.rcog.org.uk/resources/Public/pdf/endometriosis_gt_24_2006.pdf

- 7.Hughes E, Fedorkow D, Collins J, Vandekerckhove P. Ovulation suppression for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(3):CD000155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Prentice A, Deary AJ, Bland E. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD002122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Selak V, Farquhar C, Prentice A, Singla A. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(4):CD000068. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sagsveen M, Farmer JE, Prentice A, Breeze A. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for endometriosis: bone mineral density. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(4):CD001297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Yap C, Furness S, Farquhar C. Pre and post operative medical therapy for endometriosis surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD003678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Comparison of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril 2003;80:305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, Hassan D, Rosa E, Silva JC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Human Reprod 2005;20:1993-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Holmes M, Finn P, Garry R. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril 2004;82:878-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutton CJ, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1994;62:696-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fedele L, Bianchi S, Zanconato G, Bettoni G, Gotsch F. Long-term follow-up after conservative surgery for rectovaginal endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:1020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redwine DB, Wright JT. Laparoscopic treatment of complete obliteration of the cul-de-sac associated with endometriosis: long-term follow-up of en bloc resection. Fertil Steril 2001;76:358-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proctor ML, Latthe PM, Farquhar CM, Khan KS, Johnson NP. Surgical interruption of pelvic nerve pathways for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD001896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W, Garry R. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD004992. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Wong BC, Gillman NC, Oehninger S, Gibbons WE, Stadtmauer LA. Results of in vitro fertilization in patients with endometriomas: is surgical removal beneficial? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:597-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril 2005;84:1375-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matorras R, Elorriaga MA, Pijoan JI, Ramon O, Rodriguez-Escudaro FJ. Recurrence of endometriosis in women with bilateral adnexectomy (with or without total hysterectomy) who received hormone replacement therapy. Fertil Steril 2002;77:303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis.www.endometriosis.org/guidelines