Abstract

The rat streptozotocin (STZ) induced diabetes model is widely used to investigate the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. However, overt nephropathy is inexplicably slow to develop in this as compared to renal mass reduction (RMR) models. To examine if BP differences correlated with the time course of GS, BP was measured continuously throughout the course by radiotelemetry in control (n=17), partially insulin treated STZ-diabetes (average blood glucose 364±15 mg/dl) (n=15) and two normotensive RMR models (systolic BP < 140 mmHg) -uninephrectomy, UNX (n=16); and ¾ RMR by surgical excision; RK-NX (n=12) in Sprague-Dawley rats. Proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis (GS) were assessed at ∼16-20 weeks (all groups) and at 36-40 weeks (all groups except RK-NX). At 16 weeks, significantly greater proteinuria and GS had developed in the RK-NX, as compared to the other 3 groups (not different from each other). By 36-40 weeks, substantial proteinuria and GS had also developed in the UNX group, but both the control and the STZ-diabetic rats exhibited comparable modest proteinuria and minimal GS. Systolic BP (mmHg) was significantly reduced in the STZ-diabetic rats (116±1.1) as compared to both control (124±1.0) and RMR groups (128±1.2; 130±3.0) (p < 0.01). Similarly, ‘BP load’ as estimated by BP power spectral analysis was also lower in the STZ-diabetic rats. Given the known protective effects of BP reductions on the progression of diabetic nephropathy, it is likely that this spontaneous reduction in ambient BP contributes to the slow development of GS in the STZ-diabetes model as compared to the normotensive RMR models.

Keywords: Blood Pressure, Radiotelemetry, Glomerulosclerosis, Remnant Kidney, Hyperfiltration

INTRODUCTION

The progressive nature of chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been intensively investigated over the past two decades using experimental models of renal mass reduction (RMR) and diabetes. Multiple pathogenetic pathways, both hemodynamic (increased glomerular pressures and flows) and non-hemodynamic (dsregulated growth factor and cytokine production, glomerular hypertrophy and cell dysfunction), have been identified (25,26,31,38,42,52). Although the relative contribution of individual mechanisms remains controversial, it is likely that the final triggering of the cellular and molecular mediators of glomerulosclerosis (GS) results from the complex interactions between such pathways (21,34,61). In this context, the model of type I diabetes most frequently employed to investigate the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy is that of suboptimally insulin treated streptozotocin (STZ) induced diabetes in the rat (4,24,36,39,54,56,62,64,68,69). Such partial treatment (blood glucose 300-400 mg/dl) reduces osmotic diuresis and weight loss. Moreover, such rats exhibit early hyperperfusion and hyperfiltration similar to that seen in human type I diabetes, as well as substantial increases in glomerular capillary pressures (PGc) (4,39,68,69). This has led to the postulate that as in RMR models, hemodynamic injury plays a major role in the pathogenesis of diabetic GS (4,38,39,52,68,69). Moreover, kidney and glomerular hypertrophy is common to both RMR states and diabetes, suggesting that non-hemodynamic pathways for GS are also shared (24-26,31,36,42,56). A similarity in pathogenesis is also suggested by the deleterious effects of a high protein diet and protective effects of a low protein diet on GS in both diabetes and RMR models (14,33,49,52,56,69). Additionally, a great deal of in-vivo and in-vitro evidence indicates the presence of additional non-hemodynamic pathogenetic pathways, particular to hyperglycemia and the diabetic milieu, that are also expected to further potentiate the development of GS (52,62,63).

Nevertheless, despite the shared hemodynamic pathways with RMR models and the great abundance of additional non-hemodynamic mechanisms in STZ-diabetes, significant histologic GS is still very slow (>1 year) to develop as compared to the RMR models (4,31,36,52,56,60,68,69), for reasons that have remained largely obscure, as most investigations have focused on defining mechanisms that promote GS rather than those that might retard the in-vivo development of GS in this model. Given that even modest elevations in BP have been shown to accelerate, and BP reductions to slow the development and progression of both experimental and clinical diabetic and non-diabetic nephropathies (6,9,10,41,52,56), the present studies were performed to examine if differences in ambient “BP load” may account for differences in the time course of development of GS in these models. Although tail-cuff BP measurements have shown high normal or moderately elevated BP in STZ-diabetes, the data have been inconsistent and often discrepant with direct BP measurements (4,46,60,69). In view of the now clearly demonstrated limitations of the tail-cuff method (9,13,27-30,45), continuous chronic BP radiotelemetry for ∼40 weeks was utilized to examine the relationships between BP load and the development of proteinuria and GS in the partially insulin treated STZ-diabetes model compared to concurrently followed control rats and two normotensive models (systolic BP <140 mmHg) of graded RMR (uninephrectomy, UNX and ∼3/4 RMR by surgical excision) (12,28,31,32). ‘BP load’ was additionally assessed using BP power spectral analysis. Such analysis can be used to estimate and separate the BP power (energy/unit time) as consisting of two primary components; that due to its mean value (DC BP power) and that due to its fluctuations from the mean due to the heart beat and other slower neurohormonal mechanisms (AC BP power) (1,11,12,37).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eight week old male Sprague-Dawley rats (∼250g), cared for in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, were fed a standard diet and divided into 4 groups after baseline measurements of 24 hour protein excretion rates using the quantitative sulfosalicylic acid method (9,13,14,27-33). (i) Controls: rats underwent sham RMR surgery; (ii) partially insulin treated diabetes: intravenous STZ (65mg/kg) was administered through the tail vein. After confirmation of diabetes 72 hours later (initial blood glucose in all diabetic rats exceeded 300 mg/dl), Alza osmotic pumps were installed subcutaneously to deliver insulin calculated to maintain blood glucose at 300-400 mg/dl (55). Blood glucose monitoring and Alza pump and insulin dose changes were performed at 4 weekly intervals (blood glucose values ranged between 175 and 525 mg/dl and insulin doses between 3-5 units/kg/d); (iii) UNX: the right kidney was surgically removed (iv) RK-NX: the right kidney and both poles of the left kidney were surgically excised (28,31,32). Rats were followed for either 16-20 weeks before sacrifice (all four groups) or for 36-40 weeks (control, UNX and STZ-diabetes groups only, as all RK-NX rats were sacrificed at 16-20 weeks). During the last week before sacrifice, proteinuria was measured again; the rats were anesthetized, the kidneys were perfusion-fixed at the ambient BP and processed for histologic assessment as previously described (9,13,14,28-33). The data for the rats which died or had to be sacrificed prematurely, primarily because of infection and/or technical problems, are not included in the presented results (6 diabetic, 2 RKNX and 1 UNX and control rat each).

BP radiotelemetry: the rats were prepared for BP radiotelemetry (Data Sciences, Inc) as previously described (9,13,28-33) at the time of sham or RMR surgery or in the case of STZ-diabetes at the time of the initial installation of Alza (insulin) pumps. Each rat had a BP sensor (model TA11PA-C40) inserted into the aorta below the level of the renal arteries, and the radiofrequency transmitter was fixed to the peritoneum. The rats were housed individually in plastic cages placed on top of the receiver. Systolic BP was continuously recorded at 10-minute intervals using the Lab Pro Data Acquisition System with each BP reading representing the average of ∼60 readings during a 10 second interval as previously described (9,13,28-33).

Additionally, 1-3 separate BP recordings at a sampling rate of > 20 Hz over 24 hours were obtained for analysis of BP power spectra in several rats from each group between the 8th and 16th weeks. As significant differences were not observed for different recordings from an individual rat, the data were averaged for each rat before statistical analysis. The BP recordings obtained at >20 Hz were digitally resampled to 20Hz after low pass filtering to prevent aliasing. After detrending, power spectra were determined using Fast Fourier transforms and Welch’s averaged periodogram method (50% overlap of segments and a Hanning window applied) as previously described (1,12). To investigate the possible impact of circadian rhythms in BP, we conducted similar spectral analyses for each of four non-overlapping, six hour periods within the 24 hour data records, with the first period commencing at 12:00am. Although average BP and low frequency power were a little higher at night time, no strong differences in distribution of BP spectra were evident over the circadian cycle. Accordingly, the presented overall 24 hour spectrum was considered to be representative of the BP load.

Additionally, heart rate was determined from the 24 hour BP recordings. Individual heart beats were determined from the sampled blood pressure waveform by locating the peak pressure during systole and the minimal pressure during diastole. The average heart rate was then calculated by dividing the total number of heart beats occurring during the recording by the length of time of the recording.

Histology: Transverse sections through the papilla were cut at a thickness of ∼3-4 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid-Schiff. At least 100 glomeruli were examined in each animal and the percentage of glomeruli exhibiting clear histologic evidence of segmental or global GS were estimated in a blinded fashion using standard morphologic criterion as previously described (9,13,14,28-33,59). Additionally, a separate semiquantitation of mesangial matrix expansion and of GS was performed at 36-40 weeks in the control and STZ-diabetic rats using the criteria and scoring methods described by Raij et al (59).

Statistical analyses: Analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test or by Kruskall-Wallis nonparametric analysis of variance followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used, as appropriate to examine the differences between the groups (67). Because the GS data were not normally distributed, they were log transformed for statistical analysis. A p > 0.05 was considered not significant. Results are mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides the initial and follow-up body weights for all four groups at 16-20 weeks, and at 36-40 weeks for the remaining rats from the control, UNX and STZ-diabetes groups. The initial body weights were not different but the body weights of the STZ-diabetic rats were significantly lower at both the 16-20 week and 36-40 week time points. Average monthly blood glucose levels for all STZ-diabetic rats in the study was 364±15 mg/dl (403±23 mg/dl for the 6 rats followed for 16-20 wks and 338±15 mg/dl for the 9 rats followed for 36-40 wks). Table 1 also presents the course of proteinuria in all groups. Baseline proteinuria was not significantly different between the groups. Although it increased with time in all groups, the increases in the RK-NX group at 16-20 weeks were significantly greater than the other 3 groups which were not significantly different from each other. Likewise, by 36-40 weeks proteinuria was significantly greater in the UNX rats as compared to the control and STZ-diabetic rats which still did not show significant differences between them.

Table 1.

Course of body weights and proteinuria

| Group | Baseline | 16-20 wks | 36-40 wks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight(g) | Proteinuria(mg/24h) | Body weight(g) | Proteinuria(mg/24h) | Body weight(g) | Proteinuria(mg/24h) | |

| Control (n=17) | 258 ±6 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 635 ± 10 | 15.3 ± 2.1 | 752 ± 30 | 30.4 ±4.7 |

| STZ DM (n=15) | 259 ± 6 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 403 ± 23* | 18.1 ± 1.7 | 459 ± 29* | 31.1 ± 3.1 |

| UNX (n=16) | 271 ± 4 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 609 ± 22 | 20.4 ± 3.6 | 690 ± 25 | 73.5 ± 11.5* |

| RK-NX (n=12) | 264 ± 8 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 587 ± 14 | 58.1 ± 7.6* | — | — |

Results: Mean ± SEM; STZ DM, streptozotocin induced diabetes; UNX - uninephrectomy; RK-NX - ¾ renal mass reduction by surgical excision.;

p < 0.01 maximum, compared to all other groups

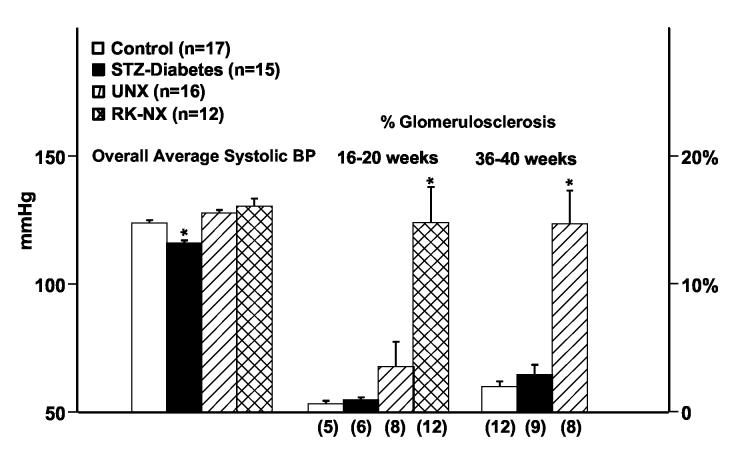

Fig. 1 shows that a pattern essentially identical to that for proteinuria was observed for GS. Significantly greater % of glomeruli exhibited GS in the RK-NX group at 16-20 weeks as compared to the other 3 groups, which were not different from each other. By 36-40 weeks, the UNX rats had developed significantly greater % GS than the control and STZ-diabetes groups which did not differ significantly. In contrast to the lack of significant differences for both proteinuria and % GS between the STZ-diabetic and control rats, when mesangial matrix expansion and GS were quantitated separately in these groups at 36-40 weeks using the scoring system of Raij et al (59), a significantly higher score was obtained for mesangial matrix expansion in diabetic as compared to controls rats (32 ± 3 vs. 19 ± 3 respectively; p < 0.01) but not for GS (7.3 ± 1.9 vs. 4.8 ± 1.1). Fig. 1 also shows that the time averaged overall systolic BP of rats with STZ-diabetes for the entire course was significantly lower than that for the other 3 groups (an average of ∼20,000 individual BP readings for the rats followed for 16-20 wks and ∼40,000 such BP readings for the rats followed for 36-40 wks). However, the time averaged systolic BP for the two RMR groups although higher, was not significantly different from that of the control rats.

Fig. 1.

Overall averaged systolic BP (mmHg) for all groups during the course and % glomerulosclerosis at sacrifice at 16-20 weeks and 36-40 weeks in control, partially insulin treated STZ-diabetes, UNX and RK-NX groups (16-20 weeks only); * p < 0.05 maximum compared to the other groups at both 16-20 weeks and 36-40 week time points.

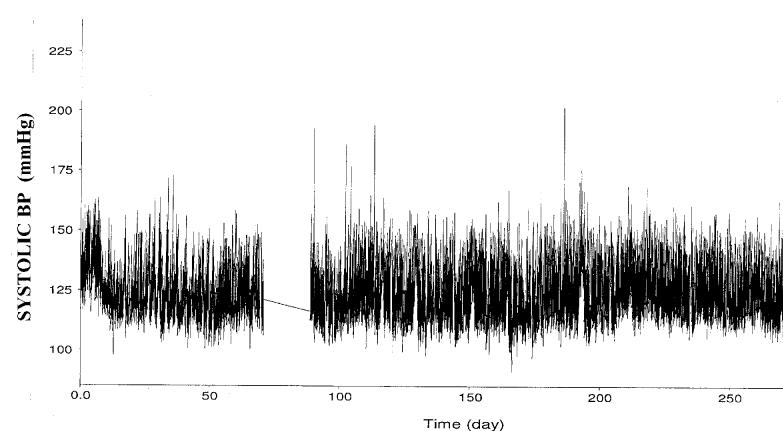

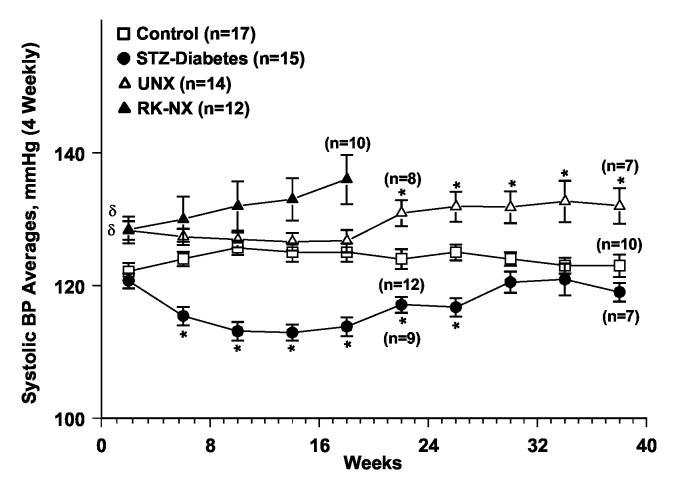

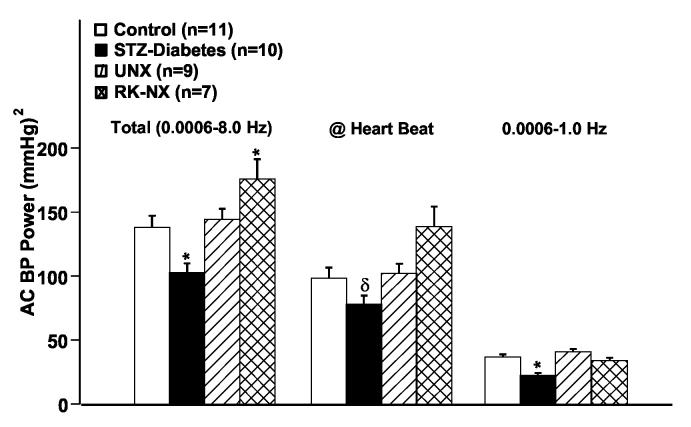

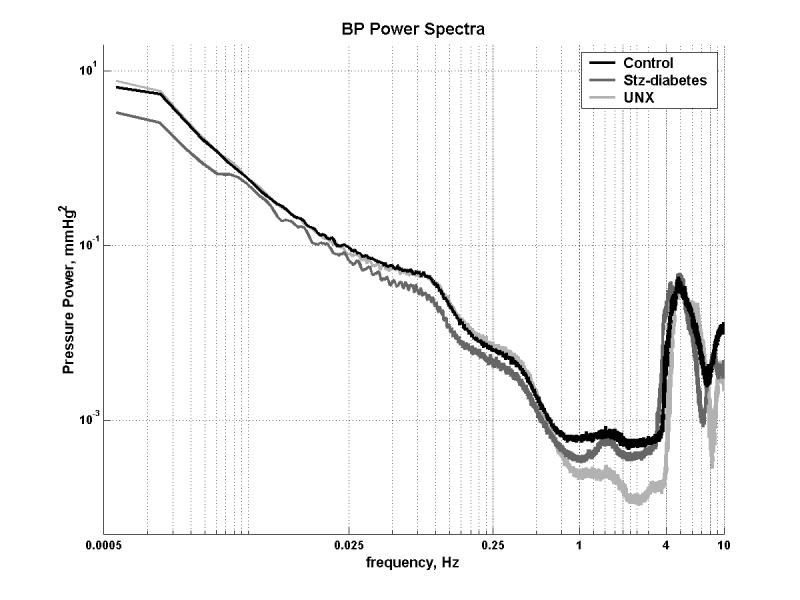

An illustration of the course of systolic BP in an individual rat with STZ-diabetes over ∼38 weeks is provided in Fig. 2a, while Fig. 2b presents the group data. Four weekly averages in each rat (∼4,000 BP readings) were calculated and meaned for each group. As can be noted, systolic BP was significantly lower in the STZ-diabetic rats at most time points during the course of the study. Fig. 3 shows the BP power spectra for the control, STZ-diabetes and the UNX groups. For clarity, the power spectra for the RK-NX rats is not shown in Fig. 3 but the quantitative results are included in Fig. 4 which presents the data for total AC BP power (0.006-8 Hz) as well as that due to its individual components at the heart beat frequency (5-7 Hz in the rat) and in the frequency range of 0.006 to 1 Hz. Because of the 1/frequency pattern of AC BP power at frequencies < heart beat, most of the AC BP power is accounted for in this frequency range (Fig. 4). As can be noted from Fig. 4, significantly less total AC BP power was present in the STZ-diabetes rats as compared to all other groups as was also true at frequencies < the heart beat frequency. However, at the heart beat frequency, statistical significance for the differences was only achieved between the STZ-diabetes and the RK-NX group. Similarly, mean BP (DC BP power) was significantly lower (P < 0.01) in the STZ-diabetes rats during these 24 hour recordings (92.9±2.3 mmHg) as compared to RK-NX (115.4±5.2) and UNX rats (103.9±2.2) but the difference with the control rats (100.6±2.5 mmHg) did not reach statistical significance (p < 0.07).

Fig. 2a.

Illustration of the course of radiotelemetry recorded systolic BP in a partially insulin treated rat with STZ-diabetes followed for ∼38 weeks. BP was recorded every 10 minutes and each point represents the average of ∼60 BP readings over a 10 second period.

Fig. 2b.

The 4 weekly averages of radiotelemetrically recorded systolic BP in control, partially insulin treated STZ-diabetes, UNX and RK-NX groups followed for 16-20 weeks or 36-40 weeks (all groups except RK-NX). The data for some of the rats in each group for the 17th-20th and 37th-40th week average is for 2-3 weeks only. * p < 0.05 maximum compared to all other groups, δ p < 0.05 compared to control and STZ-diabetes groups.

Fig. 3.

BP power spectra obtained in control (n=11) partially insulin treated STZ-diabetes (n=10) and UNX (n=9) rats between the 8th and 16th week of follow-up. BP recordings (1-3) were obtained at > 20 Hz for 24 hours in individual rats and averaged. See text for details.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative data of the analysis of BP power spectra in control, partially insulin treated STZ-diabetes, UNX and RK-NX rats. The results for the total AC BP power, the AC BP power at heart beat frequency and at frequencies of 0.006-1 Hz are presented. See text for details. * p < 0.05 maximum compared to all other groups; δ p < 0.05 compared to the RK-NX group.

Of interest, the heart rate determined from these 24 hour BP recordings obtained at 200 Hz showed that despite the lower mean BP, heart rate in the STZ-diabetes group (312 ± 8.6 beats/min) was significantly lower as compared to the control (344 ± 7.4 beats/min; p < 0.01) as well as the two RMR groups (UNX, 339 ± 5.9 beats/min; RK-NX 337 ± 2.9 beats/min; p < 0.05). The control and the RMR groups were not significantly different from each other.

DISCUSSION

The rat STZ induced model of type 1 diabetes has been extensively used to investigate the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. However, it has long been recognized that significant overt nephropathy is exceedingly slow to develop in this model although increases in albuminuria, mesangial matrix expansion, glomerular basement membrane thickening and/or other surrogate end points are noted at earlier time points (4,24,36,39,49,54,56,60,62,64,68,69). Consistent with such data, significant mesangial matrix expansion was observed after 10 months of STZ-diabetic as compared to control rats. Nevertheless, there was a minimal loss of glomerular capillaries and GS was not different between the STZ-diabetic and control rats. The slow development of GS in the present studies is therefore consistent with other long term studies that have utilized similar histologic criterion for defining GS (57,59). For instance, after 14 months of partially treated STZ-diabetes (average blood glucose 300-400 mg/dl) in the Munich-Wistar rats fed a standard protein diet, GS was only observed in ∼6% of the glomeruli by Zatz, et al. (68). Likewise, GS in only ∼12% of the glomeruli was observed after an even longer follow-up of 16 months by Anderson, et al. in the same strain (4). Similarly, GS in 9.6% of the glomeruli was reported by Remuzzi et al. after 12 months of STZ-diabetes in Sprague-Dawley rats (60). A similar lack of GS, although not as precisely quantitated, has also been noted in other long-term studies (24,36,49,56). Likewise, the time course for the development of GS after UNX in the present studies is also similar to that reported previously (8,51).

This slower development of GS in STZ-diabetes as compared to normotensive RMR models (systolic BP < 140 mmHg) is not readily explained even allowing for the fact that these models may not be strictly comparable. Rats with STZ-diabetes have been noted to not only exhibit the increases in glomerular size, pressure and flows that are postulated to lead to GS in RMR models even in the absence of diabetes (4,9,12,24,31,36,39,60,68,69), but also an abundance of additional superimposed nonhemodynamic mechanisms, believed to be triggered by hyperglycemia and/or other diabetic milieu. These include an increased activity of the local renin-angiotensin system (RAS), increased oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, increased production, expression or activity of multiple cytokines and growth factors such as transforming growth factor (TGF-β), platelet derived growth factor, connective tissue growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, altered glomerular cell metabolism and signal transduction pathways including increased activation of protein kinase ‘C’, increased production of advanced glycation end products and increased production and/or decreased degradation of extracellular matrix components (16,43,53,56,62,63).

In any event, consistent with the postulated pathogenic role of hemodynamic mechanisms, increased RMR in the present study was associated with a progressive acceleration of GS (RKNX > UNX > control). The proportionately greater vasodilation of the remnant preglomerular vasculature that we and others have previously documented as a part of the compensatory adaptive response is expected to result in greater fractional glomerular transmission of systemic BP (10,12,28,31,32,38,52). Moreover, ≥ ¾ RMR not only results in greater preglomerular vasodilation, but also impairs renal autoregulation that normally protects against the glomerular transmission of BP increases, episodic or sustained, thereby further enhancing the vulnerability to hypertensive injury (10,12,14,28,30,32). Accordingly, when severe RMR is accompanied by hypertension (5/6 renal ablation by infarction), GS is greatly accelerated and develops within 6 weeks instead of the 16-20 weeks in the normotensive surgical excision model (9,14,28,32). By contrast, UNX, at least in the absence of other concurrent renal disease, is associated with preserved autoregulation and only a relatively modest increase in the susceptibility to GS (8,10,12,51). For instance, it still takes ∼8 months for significant GS to develop after UNX in the spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) strain (23). Setting aside the contradictory results regarding renal autoregulatory impairment in experimental diabetes (17), at the very least a susceptibility to GS in STZ-diabetes comparable to that after UNX would be expected, particularly given the presence of additional non-hemodynamic mechanisms in diabetes. In fact, micropuncture measurements of PGc in STZ-diabetes in several studies have shown a PGc of ∼60 mmHg, which is higher than that reported after UNX (∼55 mmHg) and almost as high as in the conventional 5/6 ablation model (∼65 mmHg) which develops significantly more severe GS within 6 weeks (3,4,22,38,52,68).

The slow development of GS, despite an abundance of hemodynamic and non-hemodynamic mechanisms that promote GS, indicates that there must be factors associated with STZ-diabetes model in-vivo that retard GS, although none has as yet been definitively identified. The spontaneously reduced ambient BP load documented by chronic BP radiotelemetry, instead of the previously reported high normal to moderately increased tail cuff BP (140-160 mmHg) in this STZ-diabetes model (4,60,68,69), may represent one such potential mechanism (vide-infra). While the precise reasons remain to be established, the low BP does not seem to be due to plasma volume depletion (39). Measurements of plasma volume in similarly partially insulin treated STZ-diabetic rats have shown the absolute values not to be different from controls, but are in fact increased when corrected for body weight (39). The elevated atrial natriuretic peptide levels and the suppressed peripheral plasma renin levels that have been reported in these rats are consistent with such relative plasma volume expansion (4,20,48,58). Consistent with such interpretations, the significant lower heart rate in the STZ-diabetic rats as compared to controls and RMR rats also does not support the presence of a significant plasma volume deficit. Thus, it is more likely that the reduced BP in STZ-diabetes may result from a shift of the pressure natriuresis curve to the left by the characteristic renal vasodilation, just as renal vasoconstrictors shift the pressure natriuresis curve to the right (35).

Regardless of the underlying mechanisms, given that even moderate hypertension accelerates and antihypertensive therapy retards the progression of both clinical and experimental diabetic and non-diabetic nephropathies (4,6,9-11,28,32,41,52,57), a spontaneously lower ambient BP clearly has the potential to contribute to the slow development of overt nephropathy in this STZ-diabetes model. Even though the impact of superimposed pharmacologic hypertension was not directly examined in the present studies due to concerns regarding the direct BP-independent deleterious effects of such agents, substantial evidence supports the importance of BP as a determinant of GS in this model. GS is accelerated when STZ-diabetes is induced in hypertensive as compared to normotensive rats (18). Conversely, antihypertensive agents, even those that do not block the RAS, retard the development of nephropathy in both normotensive and hypertensive rats with STZ-diabetes, although the interpretations as to the precise quantitative impact are complicated by the limitations of the tail-cuff BP measurement methods used in such studies (4,19). Perhaps even more definitively, reduction in intrarenal pressures by a renal artery or aortic clip protects the ipsilateral kidney against STZ induced diabetic nephropathy but accelerates it in the contralateral kidney exposed to the higher pressures (50). Analogous effects of renal artery stenosis have been observed in diabetic patients (7).

Such data additionally indicate that the beneficial effects of a reduced BP may not only reflect an absence of the direct adverse effects of hypertension, but that reduced BP may also dampen the deleterious signal transduction pathways of other non-hemodynamic mechanisms. The development of significant mesangial matrix expansion in STZ-diabetic rats but its very slow progression to GS in the present study is consistent with such interpretations. Although such effects have not been directly investigated, there is other indirect evidence to support their existence. For instance, there is extensive in-vitro evidence for the direct BP independent tissue damaging effects of angiotensin II and aldosterone (25,26,42,66). Yet, little evidence of the activation of these deleterious pathways in-vivo is observed in the absence of elevated pressures despite substantial angiotensin and aldosterone increases during low salt intake, CHF, cirrhosis or in the clipped kidney of the 2 kidney-1 clip model (10). Nevertheless, the fact that the STZ-diabetic rats in the present study developed proteinuria and GS comparable to that observed in control rats despite a significantly lower BP suggests that such reduced pressures may not completely block the non-hemodynamic pathways. Comparable BP reductions in normal rats, at least with ACE inhibitors, have been shown to significantly retard the development of proteinuria and GS that is seen with aging in most rat strains (5,52). That the diabetic milieu contributes to the pathogenesis of GS through distinct additional, but likely interacting mechanisms with those operative after uncomplicated RMR (21,34,56,61), is also suggested by the accelerated development of GS when UNX is combined with partially treated STZ-diabetes (2).

In any event, if the above interpretations regarding the potentially protective effects of a reduced BP load on diabetic pathogenetic mechanisms are valid, they may also provide a partial explanation for the long delay (∼15 years) in the development of overt nephropathy in type I juvenile diabetic patients with lower absolute BP, despite the early onset of renal hypertrophy, hyperfiltration and presumably other non-hemodynamic mechanisms (56,64). And indeed, 24 hour ambulatory BP monitoring in such patients has revealed modest increases in BP load, due to a loss of nocturnal dip, to precede the development of overt nephropathy (47). Once nephropathy is initiated, it may not only contribute to further BP increases, but also enhance the glomerular transmission of the elevated pressures due to the renal autoregulatory impairment that seems to develop concurrently (17). Such enhanced glomerular BP transmission likely results in the acceleration of the non-hemodynamic and metabolic pathways for diabetic GS as well as suggested by the data from the 2 kidney-1 clip model (50). The initiation of such a vicious pathogenetic cycle probably accounts for the rapid downhill renal course in these patients once overt nephropathy has developed (40,56). Such interpretations are also supported by the extensive epidemiologic and clinical trial data that have demonstrated the marked adverse effects of even modest BP elevations on diabetic target organ damage including nephropathy and that have led the progressive lowering of the “optimal BP goals” for these patients (6,40,41,65).

However, given the substantially elevated PGC reported in this STZ-diabetes model, such interpretations are seemingly at odds with the current concepts that both the adverse effects of elevated BP and the beneficial effects of BP reductions are mediated though parallel changes in PGC (3,4,10,23,29,31,38,52,68). However, isolated PGc measurements may not accurately reflect the fluctuating ambient PGc profiles resulting from BP lability in states of enhanced glomerular pressure transmission (10,11,30,32). Additionally, such PGc measurements may also be compromised by surgery and anesthesia induced renin release and neurohormonal activation (10,11,13). Such limitations may in fact account for the poor correlation that has sometimes been observed between PGc and GS (25,26) even in models that demonstrate an excellent correlation between radiotelemetrically measured BP and GS (9,13,29,30). Moreover, if these PGc values are accepted as being truly representative of the ambient PGc in STZ-diabetes, the 5/6 renal ablation, and the UNX models, the inference would be inescapable that the diabetic milieu somehow protected against the adverse effects of glomerular capillary hypertension, given that the development of GS in STZ-diabetes is significantly slower and PGc significantly higher than that in UNX rats (4,22,36,68). In fact, it is more likely that such PGc of ∼60 mmHg under anesthesia may not truly reflect the ambient PGc in STZ-diabetic rats with conscious mean arterial pressures of only 90-95 mmHg that are substantially lower than the mean arterial pressures of 110-120 mmHg at which such PGc measurements have been obtained, usually after administration of plasma and/or albumin solutions to restore surgical losses (2,4,39,49,68,69). Alternatively, such differences may reflect strain differences between Sprague-Dawley and Munich-Wistar rats (49,54), as elevated PGC have been observed in the WKY and SHR with partially treated STZ-diabetes, but not in the Sprague-Dawley or Wistar rats despite the presence of significant hyperfiltration (54). However, regardless of the PGc measurements, the very slow development of overt GS despite hyperfiltration, is common to STZ-diabetes in all normotensive rat strains.

Such interpretations also do not exclude the contributions of other BP-independent mechanisms including species (genetic) differences to the observed resistance to overt nephropathy in this diabetic model (24,36,49,54,56,64). The importance of genetic factors in the susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy is strongly supported by both clinical data (44) and the recent observations examining such susceptibility in various strains of mice, although adequate BP data are not available for these studies (15,70). In this context, it is also of note that the segmental GS lesion which is the dominant lesion that is eventually observed in the partially insulin treated rodent STZ-diabetes, even when its development is accelerated by UNX or coexistent hypertension, is not a notable feature of human diabetic nephropathy (2,18,19,24,49,50,56,64), although GBM thickening and glomerular hypertrophy are observed in both (24,36,56,74). Also of interest, it is the untreated severely diabetic rat that seems to develop at least an early form of the diffuse diabetic GS with disproportionate mesangial expansion and a loss of glomerular capillary surface area (24,36,49,56,74). But, such rats do not exhibit hyperfiltration and may in fact have reduced GFR (24,39,49,54,56,64). Thus, both the untreated and partially treated STZ-diabetic rats exhibit only partial resemblance to the human diabetic nephropathy phenotype. However, while genetic differences may explain some of the differences in the glomerular lesion phenotype, they cannot explain the resistance to segmental GS in STZ-diabetes, as the rat readily develops these lesions in many diverse settings including aging (5,52,57). On the other hand, such resistance is more plausibly explained, at least in part, by the reduced BP in the rat STZ-diabetes model. Such data also underscore the need for accurate BP phenotyping for valid interpretations during investigations of susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy in experimental models.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the NIH grants DK-40426 (AKB), DK-61653 (KAG) and a VA Merit Review grant (KAG). The authors wish to thank Theresa Herbst and Rizalita Redovan for technical and Martha Prado for secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu-Amarah I, Bidani AK, Hacioglu R, Williamson GA, Griffin KA. Differential effects of salt on renal hemodynamics and potential pressure transmission in stroke-prone and stroke-resistant spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:F305–F313. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00349.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson S, Rennke HG, Brenner BM, Zayas MA, Lafferty HM, Troy JL, Sandstrom DJ. Nifedipine versus fosinopril in uninephrectomized diabetic rats. Kidney Int. 1992;41:891–897. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson S, Rennke HG, Brenner BM. Therapeutic advantage of converting enzyme inhibitors in arresting progressive renal disease associated with systemic hypertension in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1993–2000. doi: 10.1172/JCI112528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson S, Rennke HG, Garcia DL, Brenner BM. Short and long term effects of antihypertensive therapy in the diabetic rat. Kidney Int. 1989;36:526–536. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson S, Rennke HG, Zatz R. Glomerular adaptations with normal aging and with long-term converting enzyme inhibition in rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F35–F43. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.1.F35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakris GL, Williams M, Dworkin L, Elliott WJ, Epstein M, Toto R, Tuttle K, Douglas J, Hsueh W, Sowers J, for the National Kidney Foundation Hypertension and Diabetes Executive Committees Working Group Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: A consensus approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;36:646–661. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.16225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkman J, Rifkin H. Unilateral nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis (Himmelstiel-Wilson): report of a case. Metabolism. 1973;23:715. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(73)90243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beukers JJB, Van der Wal A, Hoedemaeker PJ, Weening JJ. Converting enzyme inhibition and progressive glomerulosclerosis in the rat. Kidney Int. 1987;32:794–800. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bidani AK, Griffin KA, Picken M, Lansky DM. Continuous telemetric blood pressure monitoring and glomerular injury in the rat remnant kidney model. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F391–F398. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.3.F391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bidani AK, Griffin KA. Pathophysiology of hypertensive renal damage: implications for therapy. Hypertens. 2004;44:1–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000145180.38707.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bidani AK, Griffin KA. Long-term renal consequences of hypertension for normal and diseased kidneys. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:73–80. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bidani AK, Hacioglu R, Abu-Amarah I, Williamson GA, Loutzenhiser R, Griffin KA. ‘Step’ vs ‘Dynamic’ autoregulation: implications for susceptibility to hypertensive injury. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:F113–F120. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00012.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bidani AK, Picken MM, Bakris G, Griffin KA. Lack of evidence of BP independent protection by renin-angiotensin system blockade after renal ablation. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1651–1661. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bidani AK, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Renal autoregulation and vulnerability to hypertensive injury in remnant kidney. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:1003–1010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.252.6.F1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breyer MD, Böttinger E, Brosius FC, III, Coffman TM, Harris RC, Heilig CW, Sharma K, for the AMDCC Mouse models of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:27–45. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brownlee M. Advanced protein glycosylation in diabetes and aging. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:223–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen K, Parving H-H. Autoregulation of glomerular filtration rate in patients with diabetes. In: Mogensen CE, editor. The Kidney and Hypertension in Diabetes Mellitus. 6th Edition Taylor & Francis; London and New York: 2004. pp. 495–514. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper ME, Allen TJ, O’Brien RC, Macmillan PA, Clarke B, Jerums G, Doyle AE. Effects of genetic hypertension on diabetic nephropathy in the rat functional and structural characteristics. J Hypertens. 1988;6:1009–1016. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper ME, Allen TJ, O’Brien RC, Papazoglou D, Clarke B, Jerums G, Doyle AE. Nephropathy in model combining genetic hypertension with experimental diabetes. Diabetes. 1990;39:1575–1579. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.12.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correa-Rotter R, Hostetter TH, Rosenberg ME. Renin and angiotensinogen gene expression in experimental diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 1992;41:796–804. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortes P, Yee J. Pressure-induced and metabolic alterations in the glomerulus: cytoskeletal changes. In: Mogensen CE, editor. The Kidney and Hypertension in Diabetes Mellitus. 6th Edition Taylor & Francis; London and New York: 2004. pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deen WM, Maddox DA, Robertson CR, Brenner BM. Dynamics of glomerular ultrafiltration in the rat. VII. Response to reduced renal mass. Am J Phys. 1974;227:556–562. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.227.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dworkin LD, Feiner HD. Glomerular injury in uninephrectomized spontaneously hypertensive rats. A consequence of glomerular capillary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:797–809. doi: 10.1172/JCI112377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fioretto P, Steffes MW, Brown DM, Mauer SM. An overview of renal pathology in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in relationship to altered glomerular hemodynamics. Am J Kidney Diseases. 1992;20:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fogo A, Ichikawa I. Evidence of central role of glomerular growth promoters in the development of sclerosis. Semin Nephrol. 1990;9:329–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fogo AB. Glomerular hypertension, abnormal glomerular growth, and progression of renal disease. Kidney Int. 2000;57(Suppl 75):S15–S21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffin KA, Abu-Amarah I, Picken M, Bidani AK. Renoprotection by ACE inhibition or aldosterone blockade is blood pressure dependent. Hypertens. 2003;41:201–206. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000049881.25304.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin KA, Picken M, Bidani AK. Method of renal mass reduction is a critical determinant of subsequent hypertension and glomerular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;4:2023–2031. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V4122023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffin KA, Picken M, Bidani AK. Radiotelemetric BP monitoring, antihypertensives and glomeruloprotection in remnant kidney model. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1010–1018. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin KA, Picken MM, Bidani AK. Deleterious effects on calcium channel blockade on pressure transmission and glomerular injury in rat remnant kidneys. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:798–800. doi: 10.1172/JCI118125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffin KA, Picken MM, Churchill M, Churchill P, Bidani AK. Functional and structural correlates of glomerulosclerosis after renal mass reduction in the rat. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:497–506. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V113497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffin KA, Picken MM, Bidani AK. Blood pressure lability and glomerulosclerosis after normotensive 5/6 renal mass reduction in the rat. Kidney Int. 2004;65:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffin KA, Picken M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Bidani AK. Low protein diet mediated renoprotection in remnant kidneys: renal autoregulatory vs hypertrophic mechanisms. Kidney Int. 2003;63:607–616. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruden G, Thomas S, Burt D, Lane S, Chusney G, Sacks S, Vibert GC. Mechanical stretch induces vascular permeability factor in human mesangial cells: Mechanisms of signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12112–12116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall JE, Mizelle HL, Hildebrandt DA, Brands MW. Abnormal pressure natriuresis. A cause or a consequence of hypertension? Hypertens. 1990;15:547–559. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirose K, Østerby R, NozaWA M, Gunderson HJG. Development of glomerular lesions in experimental long-term diabetes in the rat. Kidney Int. 1982;21:689–695. doi: 10.1038/ki.1982.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holstein-Rathlou H-N, He J, Wagner AJ, Marsh DJ. Patterns of blood pressure variability in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Am j Physiol. 1995;269:R1230–R1239. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.5.R1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hostetter TH, Rennke HG, Brenner BM. The case for intrarenal hypertension in the initiation and progression of diabetic and other glomerulopathies. Am J Med. 1982;72:375–380. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90490-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hostetter TH, Troy JL, Brenner BM. Glomerular hemodynamics in experimental diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 1981;19:410–415. doi: 10.1038/ki.1981.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hovind P, Rossing P, Tarnow L, Smidt UM, Parving H-H. Progression of diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2001;59:702–709. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention. Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ketteler M, Noble NA, Border WA. Transforming growth factor-β and angiotensin II: The missing link from glomerular hyperfiltration to glomerulosclerosis? Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:279–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koya D, Jirousek MR, Lin Y-W, Ishii H, Kuboki K, King GL. Characterization of protein kinase C-β isoform activation on the gene expression of transforming growth factor-β, extracellular matrix components, and prostanoids in the glomeruli of diabetic rats. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:115–126. doi: 10.1172/JCI119503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krolewski AS. Genetics of diabetic nephropathy: Evidence for major and minor gene effects. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1582–1596. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurtz TW, Griffin KA, Bidani AK, Davisson RL, Hall JE. AHA Scientific Statement. Recommendation for blood pressure measurements in humans and animals. Part 2: Blood pressure measurements in experimental animals. Hypertens. 2005;45:299–310. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150857.39919.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kusaka M, Kishi K, Sokabe H. Does so-called streptozotocin hypertension exist in rats? Hypertens. 1987;10:517–521. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.10.5.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lurbe E, Redon J, Kesani A, Pascual M, Tacons J, Alvarez V, Battle D. Increase in nocturnal blood pressure and progression to microalbuminuria in type I diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:797–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsubara H, Mori Y, Yamamoto J, Inada M. Diabetes-induced alterations in atrial natriuretic peptide gene expression in Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res. 1990;67:803–813. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.4.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mauer SM, Steffes MW, Azar S, Brown DM. Effects of dietary protein content in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Kidney Int. 1989;35:48–59. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mauer SM, Steffes MW, Azar S, Sandberg SK, Brown DM. The effects of Goldblatt hypertension on development of the glomerular lesions of diabetes mellitus in the rat. Diabetes. 1978;27:738–744. doi: 10.2337/diab.27.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagata M, Scharer K, Kriz W. Glomerular damage after uninephrectomy in young rats. I. Hypertrophy and distortion of capillary architecture. Kidney Int. 1992;42:136–147. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neuringer JR, Brenner BM. Hemodynamic theory of progressive renal disease: a 10-year update in brief review. Am J Kidney Disease. 1993;22:98–104. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S-I, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, Yorek MA, Beebe D, Oates PJ, Hames H-P. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature. 2000;404:787–790. doi: 10.1038/35008121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Donnell MP, Kasiske BL, Keane WF. Glomerular hemodynamic and structural alterations in experimental diabetes mellitus. FASEB J. 1988;2:2339–2347. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.8.3282959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohishi K, Okweze MI, Vari RC, Carmines PK. Juxtamedullary microvascular dysfunction during the hyperfiltration stage of diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F399–F405. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.1.F99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olson JL. Diabetes mellitus. In: Jennette JC, Olson JL, Schwartz MM, Silva FG, editors. Heptinstall’s Pathology of the Kidney. Fifth Edition Lippincott - Raven; 1998. pp. 1247–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olson JL. Progression of renal disease. In: Jennette JC, Olson JL, Schwartz MM, Silva FG, editors. Heptinstall’s Pathology of the Kidney. Fifth Edition Lippincott - sRaven; Philadelphia: 1998. pp. 137–168. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ortola FV, Ballermann BJ, Anderson S, Mendez RE, Brenner BM. Elevated plasma atrial natriuretic peptide levels in diabetic rats. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:670–674. doi: 10.1172/JCI113120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raij L, Azar S, Keane W. Mesangial immune injury, hypertension, and progressive glomerular damage in Dahl rats. Kidney Int. 1984;26:137–143. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Remuzzi A, Perico N, Amuchastegui CS, Malanchini B, Mazerska M, Battaglia C, Bertani T, Remuzzi G. Short- and long-term effect of angiotensin II receptor blockade in rats with experimental diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;4:40–49. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shankland SJ, Ly H, Tahi K, Scholey JW. Increased glomerular capillary pressure alters glomerular cytokine expression. Circ Res. 1994;75:844–853. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.5.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma K, Ziyadeh FN. Perspectives in diabetes. Hyperglycemia and diabetic kidney disease. The case for transforming growth factor-β as a key mediator. Diabetes. 1995;44:1139–1146. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheetz MJ, King GL. Molecular understanding of hyperglycemia’s adverse effects for diabetic complications. JAMA. 2002;288:2579–2588. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.20.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steffes MW, Mauer SM. International Review of Experimental Pathology. Academic Press, Inc.: 1984. Diabetic glomerulopathy in man and experimental animal models; pp. 147–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.UK Prospective Diabetes Group Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolf G, Ziyadeh FN. The role of angiotensin II in diabetic nephropathy: Emphasis on nonhemodynamic mechanisms. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Woolson RF. Statistical methods for the analysis of biomedical data. Wiley series, in Probability and Mathematical Statistics, Philadelphia, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. pp. 314–344. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zatz R, Dunn BN, Meyer TW, Anderson S, Rennke HG, Brenner BM. Prevention of diabetic glomerulopathy by pharmacological amelioration of glomerular capillary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1925–1930. doi: 10.1172/JCI112521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zatz R, Meyer TW, Rennke HG, Brenner BM. Predominance of hemodynamic rather than metabolic factors in the pathogenesis of diabetic glomerulopathy. Proc Natl Acad. 1985;82:5963–5967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zheng F, Striker GE, Esposito C, Lupia E, Striker LJ. Strain differences rather than hyperglycemia determine the severity of glomerulosclerosis in mice. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1999–2007. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]