Abstract

Antagonists of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) are being developed for the treatment of various cancers. In this study, we investigated the effectiveness of treatment with GHRH antagonist JMR-132 alone and in combination with docetaxel chemotherapy in nude mice bearing MX-1 human breast cancers. Specific high-affinity binding sites for GHRH were found on MX-1 tumor membranes using ligand competition assays with 125I-labeled GHRH antagonist JV-1-42. JMR-132 displaced radiolabeled JV-1-42 with an IC50 of 0.14 nM, indicating a high affinity of JMR-132 to GHRH receptors. Treatment of nude mice bearing xenografts of MX-1 with JMR-132 at 10 μg per day s.c. for 22 days significantly (P < 0.05) inhibited tumor volume by 62.9% and tumor weight by 47.8%. Docetaxel given twice at a dose of 20 mg/kg i.p. significantly reduced tumor volume and weight by 74.1% and 58.6%, respectively. Combination treatment with JMR-132 (10 μg/day) and docetaxel (20 mg/kg i.p.) led to growth arrest of most tumors as shown by an inhibition of tumor volume and weight by 97.7% and 95.6%, respectively (P < 0.001). Because no vital cancer cells were detected in some of the excised tumors, a total regression of the tumors was achieved in some cases. Treatment with JMR-132 also strongly reduced the concentration of EGF receptors in MX-1 tumors. Our results demonstrate that GHRH antagonists might provide a therapy for breast cancer and could be combined with docetaxel chemotherapy to enhance the efficacy of treatment.

Keywords: breast cancer, cancer therapy, chemotherapeutic agents, growth hormone-releasing hormone receptors

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy among women in the Western world and ranks second as a cause of cancer-related deaths. In 2006, ≈40,000 women in the United States were expected to die from breast cancer (1). Most patients succumb to this malignancy not because of their primary cancer, but because of metastases (2–6). Despite the use of endocrine therapy, systemic chemotherapy, and novel approaches, such as the treatment with monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (Herceptin) against the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2), metastatic disease remains generally incurable, with a median survival time of 2–3 years (2–6). Therefore, it is mandatory to develop more effective treatment strategies with low toxicity for the treatment of breast cancer.

In an endeavor to develop a class of antineoplastic agents, various antagonistic analogs of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) were synthesized in our laboratory in recent years (7–9). GHRH antagonists inhibit the growth of various experimental human cancers, such as pancreatic (10), colorectal (11), prostatic (12–14), breast (15), and renal cancers (16); glioblastomas (17), osteosarcomas, and Ewing sarcomas (18, 19); small cell lung carcinomas and non-small small cell lung carcinomas (20–22). GHRH antagonists suppress tumor growth through indirect and direct pathways. The indirect endocrine mechanism operates through the suppression of the GH release from the pituitary, and the resulting inhibition of the hepatic production of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) (7–9).

In recent in vivo experiments, the growth of various human cancers was inhibited in the absence of any significant effects on serum IGF-I when lower doses of GHRH antagonists or more recently developed analogs with different structural features, such as antagonists JV-1-36, JV-1-38, and MZ-J-7-118 were used (7, 8, 20, 23, 24). It was also observed that GHRH antagonists can inhibit the proliferation of diverse cancer lines by direct action in vitro under conditions in which the contribution of the hypothalamic GHRH/pituitary growth hormone/hepatic IGF-I axis is clearly excluded (7, 10, 14, 23, 25–30). In addition, the expression of mRNA for GHRH and the presence of biologically or immunologically active GHRH was demonstrated in several malignant tumors, including cancers of the breast, endometrium, and ovary; small cell lung carcinomas; prostate and bone sarcomas; and lymphomas (7–9). These results suggest that GHRH can function as an autocrine growth factor (7–9). Furthermore, splice variants of GHRH receptor were detected in many human tumors (7–9). Altogether, these findings indicate that the main mechanism responsible for tumor inhibition could be a direct effect of the GHRH antagonists on the tumor tissue due to the blocking of action of tumoral GHRH (7–9).

Taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel (Taxotere) have been observed to affect several signaling pathways, bringing about cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Some of the most common changes after treatment are Bcl-2 phosphorylation (31) and the activation of mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint (32). Taxanes are now emerging as potent therapeutic tools in the treatment of early and metastatic breast cancer (33–35).

Recently it was demonstrated in early and late stage breast cancer that paclitaxel and docetaxel can be effectively combined with trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks the mitogenic pathway through the HER-2 receptor (36–39).

A new approach of effective cancer therapy could be the combination of chemotherapeutic agents such as the taxanes with growth factor inhibitors such as GHRH antagonists. The current study was performed to assess the antitumor effect of a combination therapy of docetaxel with the GHRH antagonist JMR-132 as compared with monotherapies with either agent in experimental human MX-1 breast cancers.

Results

Effect of GHRH Antagonist JMR-132 on the Growth of MX-1 Human Breast Cancer.

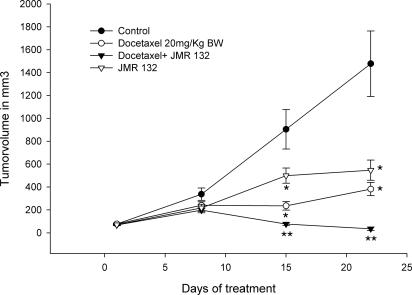

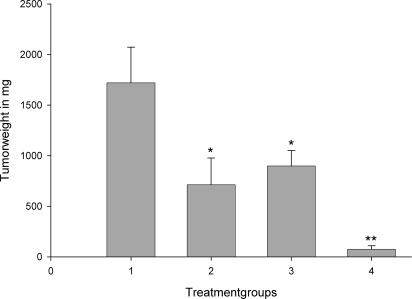

Treatment with GHRH antagonist JMR-132 at the dose of 10 μg/day was initiated after the tumors reached a volume of ≈70 mm3. After 3 weeks of treatment the mice were killed under deep anesthesia. Tumor volume and weight was significantly (P < 0.05) inhibited by JMR-132 (Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 1) by 63% and 48%, respectively, as compared with control animals. JMR-132 at 10 μg/day significantly (P < 0.05) extended tumor doubling time as compared with controls (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of treatment with GHRH antagonist JMR-132 given s.c. at a dose of 10 μg/day, docetaxel given i.p. at a dose of 20 milligrams per kilogram of body weight on days 1 and 5, or the combination of JMR-132 with docetaxel on the tumor volume of MX-1 human breast cancer xenografted s.c. into nude mice. Vertical bars indicate SE. *, P < 0.001 vs. control; **, P < 0.001 vs. control and the groups receiving single agents.

Fig. 2.

Effect of treatment with GHRH antagonist JMR-132 given s.c. at a dose of 10 μg/day (column 3), docetaxel given i.p. at a concentration of 20 milligrams per kilogram of body weight on days 1 and 5 (column 2), or the combination of JMR-132 with docetaxel (column 4) on the tumor weight of MX-1 human breast cancer xenografted s.c. into nude mice. Vertical bars indicate SE. *, P < 0.001 vs. control; **, P < 0.001 vs. control (column 1) and the groups receiving single agents.

Table 1.

Effects of therapy with GHRH antagonists JMR-132 and docetaxel alone and their combinations on the growth of MX-1 human breast cancer xenografted into nude mice

| Treatment | Initial tumor volume, mm3 | Final tumor volume, mm3 (% inhibition) | Tumor weight, mg (% inhibition) | Tumor doubling time, days | Body weight on day 24, g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 77.2 ± 5.6 | 1,478.1 ± 286.5 | 1,720.9 ± 352.4 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 26.3 ± 1.3 |

| JMR-132 at 10 μg/day | 71.2 ± 5.6 | 547.3 ± 88.1 (62.9)* | 899.1 ± 152.5 (47.8)* | 7.9 ± 0.6* | 24.6 ± 1.3 |

| Docetaxel at 20 milligrams per kilogram of body weight | 76.9 ± 9.2 | 382.2 ± 57.5 (74.1)** | 712.7 ± 263.9 (58.6)* | 10.3 ± 0.9** | 24.0 ± 1.4 |

| Docetaxel and JMR-132 | 69.1 ± 6.4 | 33.7 ± 14.3 (97.7)** | 75.0 ± 35.2 (95.6)** | NC | 21.7 ± 1.5 |

NC, not calculated.

*, P < 0.05

**, P < 0.001 vs. control.

Effect of Docetaxel on the Growth of MX-1 Human Breast Cancer.

When nude mice xenografted with human MX-1 tumors received docetaxel alone at a dosage of 20 mg/kg, administered i.p. at days 1 and 5, tumor volume was inhibited by 29% on day 8. On day 15, the growth reduction became significant (P < 0.05) (58.6%) as compared with the control group (Fig. 1). Significant (P < 0.001) reduction of the tumor volume by 74.1% was observed after 3 weeks of treatment with docetaxel (Table 1). Tumor weight was reduced significantly (P < 0.05) by 59% as compared with the control group. (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The tumor doubling time was significantly (P < 0.001) extended from 6.0 to 10.3 days.

Effect of GHRH Antagonist JMR-132 in Combination with Docetaxel on the Growth of MX-1 Human Breast Cancer.

One group of mice with MX-1 tumors was treated with GHRH antagonist JMR-132 at a dose of 10 μg/day and docetaxel i.p. at 20 mg/kg on days 1 and 5. Combination therapy showed a significant tumor inhibition (P < 0.001) after 15 days, followed by growth arrest of the tumors in most of the animals after 3 weeks of treatment (P < 0.001). A significant (P < 0.001) reduction of the tumor volume by 97.7% was achieved in this group (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Tumor weight was significantly (P < 0.001) reduced by 95.6% by the combination therapy (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Thus, the mean tumor weight in the treatment group was 75.0 ± 35.2 mg as compared with 1,720.9 ± 352.4 mg in the control group (P < 0.001). The combination of Docetaxel and JMR 132 showed a significant (P < 0.001) inhibition of tumor volume as compared with the groups of single agents applied (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Combination therapy led to total regression of some of the tumors because the histology of some samples showed no evidence of residual human breast cancer tumor tissue. (data not shown). Because of the regression of a majority of the tumors, tumor-doubling time could not be evaluated in the group of docetaxel in combination with JMR-132.

Toxicity.

No signs of drug-induced toxicity were observed in any of the groups, as reflected by nonsignificant differences in body weight among the treated groups and the control animals.

Binding Assays for GHRH Receptors in MX-1 Tumors.

The presence of GHRH receptors was assessed by radioligand binding assays in control tumors. Binding studies demonstrated the presence of a single class of specific, high-affinity (dissociation constant, Kd = 2.31 ± 0.41 nM) binding sites for GHRH antagonist JV-1-42 in the membrane preparation of MX-1 tumors, with a mean maximal binding capacity (Bmax) of 213.7 ± 14.1 femtomoles per milligram of membrane protein.

In a competition displacement experiment on s.c. grown MX-1 tumors from the control group, GHRH antagonist JMR-132 was able to displace the [125I]JV-1-42 radioligand with an IC50 of 0.14 nM. This IC50 value indicates a high affinity binding of JMR-132 to GHRH receptors expressed on MX-1 tumors.

Effects of GH-RH Antagonist JMR-132 and Docetaxel on the Binding Characteristics of EGF Receptors in MX-1 Tumors.

Specific high-affinity binding sites for EGF were found on the control MX-1 tumors. Daily administration of GHRH antagonist JMR-132 and treatment with JMR-132 in combination with docetaxel significantly (P < 0.01) reduced the maximal binding capacity of receptors for EGF by 68–69% (Table 2). Treatment of MX-1 tumors with docetaxel alone did not cause any reduction in the concentrations of EGF receptors (Table 2.). No significant differences in the binding affinity (Kd) of EGF receptors was observed between the untreated and treated groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Binding characteristics of EGF receptors on membranes of human MX-1 breast cancers

| Treatment | EGF receptors |

|

|---|---|---|

| Kd, nM | Bmax, femtomoles per milligram of membrane protein | |

| Control | 1.01 ± 0.2 | 285.7 ± 19.2 |

| JMR-132 | 0.94 ± 0.2 | 92.4 ± 2.3* |

| Docetaxel | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 278.1 ± 36.4 |

| JMR-132 and docetaxel | 0.95 ± 0.1 | 89.5 ± 1.6* |

*, P < 0.01 vs. control.

Discussion

Novel approaches to the therapy of many cancers could be based on the use of compounds that block the autocrine/paracrine and endocrine stimulatory pathways that promote tumor growth (7–9). GHRH antagonists belonging to this class of antitumor agents were initially developed for treatment of cancers that depend on endocrine hepatic IGF-I stimulated by pituitary growth hormone (18). However, recent evidence points to a major role of local GHRH in various cancers and its tumoral receptors in the pathogenesis of many malignancies. Various findings suggest that most of the antitumor effects of the GHRH antagonists could be mediated through a direct action on the cancer cells (7, 24, 28, 29, 40–44). Thus, a large number of breast cancer specimens were found to express mRNA for GHRH and immunoreactive GHRH protein (45). Moreover, 25% of human breast carcinomas overexpress specific splice variants of the GHRH receptor, which are fully functional and bind GHRH with high affinity (46). In addition, the growth of T47D cells, which also possess the splice variant receptor, was stimulated by GHRH and dose-dependently inhibited by GHRH antagonist JV-1–38 in vitro (44). These results indicate that GHRH may be a growth factor in breast cancer. The current study demonstrates the presence of specific, high-affinity binding sites for GHRH on MX-1 tumor membranes. GHRH antagonist JMR-132 displayed high binding affinities to tumoral GHRH receptors and effectively inhibited growth of MX-1 tumors in vivo.

Taxanes such as docetaxel and paclitaxel have been recently established as first-line therapeutic agents for early and metastatic breast cancer. It has been demonstrated in various studies that this class of substances can be effectively combined with the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab, which blocks the tumoral HER-2 receptor and thereby interferes with the mitogenic cascade (47–49). Thus, taxanes are likely candidates for treatment combinations with growth factor inhibitors.

In the present study, we observed a significant inhibition of tumor growth with JMR-132 of ≈60%, which is in accord with our results from a previous investigation performed with GHRH antagonists MZ-5-156 or JV-1-36 (14). The antitumor effect with docetaxel was somewhat more pronounced and in the range of 80%. The combination of JMR-132 and docetaxel led to total growth arrest of the tumors in most animals. Inhibition of tumor weight by this combination was nearly 100%. Thus, the use of both compounds together resulted in considerable synergy and eradicated the tumor in some animals as reflected by the histology of samples, which showed no evidence of residual tumor tissue. Combination therapy seemed to be devoid of major side effects given that no signs of toxicity were observed in animals subjected to treatment with both compounds. No side effects after treatment with GHRH antagonists as single agents have been found so far in animal models (7).

The EGF/HER receptors can be suitable targets for anticancer drugs. A monoclonal antibody (trastuzumab or Herceptin) that targets erbB2/HER-2 has been approved for the treatment of breast cancer. The present study demonstrates that the antitumoral effect exerted by GHRH antagonist JMR-132 is due in part to interference with the mechanism involving the EGF receptor/HER family. Our work shows that the modern GHRH antagonist JMR-132 caused a very substantial down-regulation of EGF binding sites in MX-1 tumors. Thus, it could be assumed that some antitumor activity of GHRH antagonists might be exerted by the inhibition of the EGF/EGF receptor pathways through a decrease in the Bmax of EGF receptors. Given that many neoplasms, including breast cancers, express both EGF and HER-2, the development of agents, such as our GHRH analogs, that inhibit these receptors is an attractive therapeutic target.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that GHRH antagonists are effective in the treatment of estrogen-independent breast cancers and can be combined with taxane chemotherapy. It is possible that the development of GHRH antagonists might lead to improved therapy of early and late stage breast cancers.

Materials and Methods

Peptides and Chemicals.

The GHRH antagonist JMR-132 [PhAc0,d-Arg2,Phe(4-Cl)6,Ala8,Har9,Tyr(Me)10,His11,Abu15,His20, Nle27,d-Arg28,Har29] human GHRH (1-29)-NH2, where Abu is α-aminobutyric acid, Har is homoarginine, Nle is norleucine, PhAc is phenylacetyl, and Tyr(Me) is O-methyltyrosine, was synthesized in our laboratory by solid phase methods (7, 50). Its structure corresponds to Ala8-MZ-J-7-132 [PhAc-Tyr1, d-Arg2, Phe(4-Cl)6,Har9,Tyr(Me)10,His11,Abu15,His20,Nle27,d-Arg28,Har29] human GHRH(1-29)NH2, where Ac is acetyl. Analog JV-1-42 was described previously (40). Docetaxel was purchased from ChonTech (Waterford, CT). Matrigel (phenol red-free) was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). For daily injection, GHRH antagonist was dissolved in 0.1% DMSO in 10% aqueous propylene glycol solution (vehicle solution).

Cell Lines and Animals.

Estrogen-independent, Doxorubicin-resistant human breast cancer xenograft MX-1, originating from a surgical explant, was kindly donated by Richard Camalier (National Cancer Institute Frederick Cancer and Development Center, Frederick, MD). Tumors were maintained in donor animals.

Five- to 6-week-old female athymic nude mice (Ncr nu/nu) were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). The animals were housed in sterile cages under laminar flow hoods in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light/12-h dark schedule. They were fed autoclaved chow and water ad libitum.

In Vivo Experiments.

Small pieces of MX-1 breast cancer were transplanted s.c. into donor female nude mice. After 3 weeks, tumor tissue grown in donor animals was minced and passed through a wire mesh. A suspension of 150 μl was inoculated s.c. into experimental female nude mice. The experiment was initiated when MX-1 tumors had reached a volume of ≈70 mm3. Mice were divided into four experimental groups of 10 animals each: group 1, control; group 2, JMR-1–32 s.c. at a dose of 10 μg/day; group 3, docetaxel at a dose of 20 mg/kg i.p. on days 1 and 5; group 4, docetaxel at the dose of 20 mg/kg i.p. on days 1 and 5 and JMR-132 at a dose of 10 μg/day s.c. The weight of the animals was recorded weekly. Tumor volume (length × width × height × 0.5236) and body weight also were measured weekly. At the end of the experiment, mice were killed under anesthesia, tumors were excised and weighed, and necropsy was performed. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the welfare of animals in experiments. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the VA medical Center in New Orleans reviewed the protocol for the animal experiments and gave full approval.

The trial was ended 3 weeks after the initiation of the treatment, mice were killed under anesthesia, and necropsy was preformed. Tumors and organs were removed and weighed.

Receptor Binding Assays.

Preparation of the membrane fractions from MX-1 human breast cancers and receptor-binding studies were performed as described previously (40). Binding characteristics of receptors for GHRH and EGF were determined by in vitro ligand competition assays based on the binding of radiolabeled GHRH antagonist JV-1-42 and EGF to tumor membrane fractions (40). Receptor binding affinity (IC50) of GHRH antagonist JMR-132 to membranes of s.c. grown MX-1 tumors from the control group also was measured in displacement experiments based on the competitive inhibition of [125I]JV-1-42 binding by various concentrations (10−12 to 10−6 M) of JMR-132. IC50 is defined as the dose of JMR-132 causing 50% inhibition of the specific binding of [125I]JV-1-42.

Statistical Analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Results were compared by Student's t test. P < 0.05 was accepted as a statistically significant difference.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Service of the Veterans Affairs Department and a grant from Zentaris GmbH (Frankfurt am Main, Germany) to Tulane University (all to A.V.S.).

Abbreviations

- GHRH

growth hormone-releasing hormone

- HER-2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- IGF-I

insulin-like growth factor I.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Tulane University has applied for a patent on the GHRH antagonist JMR-132 cited in this paper. J.L.V. and A.V.S. are coinventors on that patent. However, A.V.S. is now affiliated with the University of Miami.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampath D, Discafani CM, Loganzo F, Beyer C, Liu H, Tan X, Musto S, Annable T, Gallagher P, Rios C, Greenberger LM. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:873–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Todd M, Shoag M, Cadman E. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:406–408. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.6.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborne CK. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1609–1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811263392207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleator S, Tsimelzon A, Ashworth A, Dowsett M, Dexter T, Powles T, Hilsenbeck S, Wong H, Osborne CK, O'Connell P, Chang JC. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;95:229–233. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varga Z, Caduff R, Pestalozzi B. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:136–141. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schally A, Varga JL. Combinatorial Chem High Throughput Screening. 2006;9:163–170. doi: 10.2174/138620706776055449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schally AV, Comaru-Schally AM, Nagy A, Kovacs M, Szepeshazi K, Plonowski A, Varga JL, Halmos G. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2001;22:248–291. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schally AV, Varga JL. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1999;10:383–391. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szepeshazi K, Schally AV, Groot K, Armatis P, Hebert F, Halmos G. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:128–136. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szepeshazi K, Schally AV, Groot K, Armatis P, Halmos G, Herbert F, Szende B, Varga JL, Zarandi M. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1724–1731. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jungwirth A, Schally AV, Pinski J, Halmos G, Groot K, Armatis P, Vadillo-Buenfil M. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1585–1592. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamharzi N, Schally AV, Koppan M, Groot K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8864–8868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Letsch M, Schally AV, Busto R, Bajo AM, Varga JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1250–1255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337496100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahan Z, Varga JL, Schally AV, Rekasi Z, Armatis P, Chatzistamou L, Czompoly T, Halmos G. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;60:71–79. doi: 10.1023/a:1006363230990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jungwirth A, Schally AV, Pinski J, Groot K, Armatis P, Halmos G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5810–5813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiaris H, Schally AV, Varga JL. Neoplasia. 2000;2:242–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinski J, Schally AV, Groot K, Halmos G, Szepeshazi K, Zarandi M, Armatis P. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1787–1794. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braczkowski R, Schally AV, Plonowski A, Varga JL, Groot K, Krupa M, Armatis P. Cancer. 2002;95:1735–1745. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szereday Z, Schally AV, Varga JL, Kanashiro CA, Hebert F, Armatis P, Groot K, Szepeshazi K, Halmos G, Busto R. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7913–7919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiaris H, Schally AV, Varga JL, Groot K, Armatis P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14894–14898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinski J, Schally AV, Jungwirth A, Groot K, Halmos G, Armatis P, Zarandi M, Vaudillo-Buenfil M. Int J Oncol. 1996;9:1099–1105. doi: 10.3892/ijo.9.6.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatzistamou I, Schally AV, Varga JL, Groot K, Armatis P, Busto R, Halmos G. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2144–2152. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plonowski A, Schally AV, Busto R, Krupa M, Varga JL, Halmos G. Peptides. 2002;23:1127–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatzistamou I, Schally AV, Varga JL, Groot K, Busto R, Armatis P, Halmos G. Anticancer Drugs. 2001;12:761–768. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szepeshazi K, Schally AV, Armatis P, Groot K, Hebert F, Feil A, Varga JL, Halmos G. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4371–4378. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rekasi Z, Varga JL, Schally AV, Halmos G, Armatis P, Groot K, Czompoly T. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2120–2128. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busto R, Schally AV, Varga JL, Garcia-Fernandez MO, Groot K, Armatis P, Szepeshazi K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11866–11871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182433099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Busto R, Schally AV, Braczkowski R, Plonowski A, Krupa M, Groot K, Armatis P, Varga JL. Regul Pept. 2002;108:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plonowski A, Schally AV, Letsch M, Krupa M, Hebert F, Busto R, Groot K, Varga JL. Prostate. 2002;52:173–182. doi: 10.1002/pros.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berchem GJ, Bosseler M, Mine N, Avalosse B. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:535–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavelle F, Bissery MC, Combeau C, Riou JF, Vrignaud P, Andre S. Semin Oncol. 1995;22:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexandre J, Bleuzen P, Bonneterre J, Sutherland W, Misset JL, Guastalla J, Viens P, Faivre S, Chahine A, Spielman M, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:562–573. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravdin PM, Burris HA, III, Cook G, Eisenberg P, Kane M, Bierman WA, Mortimer J, Genevois E, Bellet RE. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2879–2885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.12.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson IC, Berry DA, Demetri GD, Cirrincione CT, Goldstein LJ, Martino S, Ingle JN, Cooper MR, Hayes DF, Tkaczuk KH, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:976–983. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marty M, Cognetti F, Maraninchi D, Snyder R, Mauriac L, Tubiana-Hulin M, Chan S, Grimes D, Anton A, Lluch A, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4265–4274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esteva FJ, Valero V, Booser D, Guerra LT, Murray JL, Pusztai L, Cristofanilli M, Arun B, Esmaeli B, Fritsche HA, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1800–1808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher B, Anderson S, Tan-Chiu E, Wolmark N, Wickerham DL, Fisher ER, Dimitrov NV, Atkins JN, Abramson N, Merajver S, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:931–942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Halmos G, Schally AV, Czompoly T, Krupa M, Varga JL, Rekasi Z. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4707–4714. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rekasi Z, Czompoly T, Schally AV, Halmos G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10561–10566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180313297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chopin LK, Herington AC. Prostate. 2001;49:116–121. doi: 10.1002/pros.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiaris H, Schally AV, Busto R, Halmos G, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Varga JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:196–200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012590999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia-Fernandez MO, Schally AV, Varga JL, Groot K, Busto R. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;77:15–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1021196504944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahan Z, Arencibia JM, Csernus VJ, Groot K, Kineman RD, Robinson WR, Schally AV. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:582–589. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.2.5487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chatzistamou I, Schally AV, Kiaris H, Politi E, Varga J, Kanellis G, Kalofoutis A, Pafiti A, Koutselini H. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:391–396. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1510391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plosker GL, Keam SJ. BioDrugs. 2006;20:259–262. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200620040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Esteva FJ. Oncology. 2002;16:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slamon D, Pegram M. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varga JL, Schally AV. In: Handbook of Peptides. Kastin A, editor. New York: Elsevier-Academic; 2006. pp. 483–489. [Google Scholar]