Summary

In Bacillus subtilis, glutamate synthase, a major enzyme of nitrogen metabolism, is encoded by the gltAB operon. Significant expression of this operon requires the activity of a LysR-family protein, GltC, encoded by the divergently transcribed gene. We purified a soluble, active form of GltC and found that it requires α-ketoglutarate, a substrate of glutamate synthase, to fully activate gltA transcription in vitro, and that its activity is inhibited by glutamate, the product of glutamate synthase. GltC regulated gltAB transcription through binding to three dyad-symmetry elements, Box I, Box II and Box III, located in the intergenic region of gltC and gltA. Purified GltC bound almost exclusively to Box I and only marginally activated gltAB transcription. Glutamate-bound GltC bound to Box I and Box III, and repressed gltAB transcription. In the presence of α-ketoglutarate, GltC bound to Box I and Box II, stabilized binding of RNA polymerase to the gltA promoter, and activated gltAB transcription. The binding of GltC to Box II, which partially overlaps the -35 region of the gltA promoter, seems to be essential for activation of the gltAB operon. Due to the high concentration of glutamate in B. subtilis cells grown under most conditions, alterations of α-ketoglutarate concentration seem to be crucial for modulation of GltC activity and gltAB expression.

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis, glutamate biosynthesis, GltC, α-ketoglutarate, LysR family

Introduction

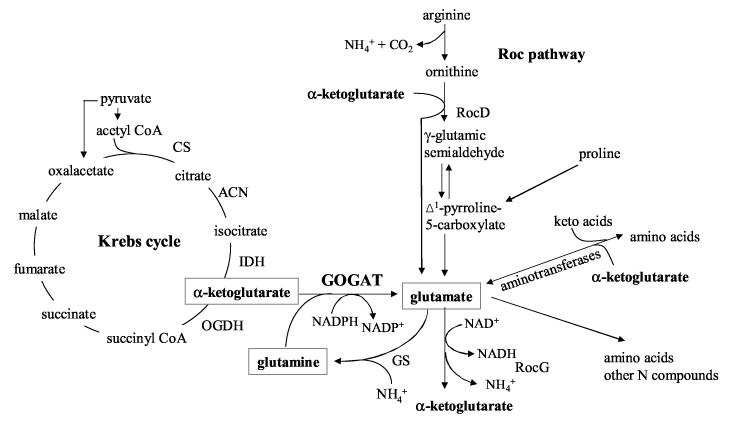

The biosynthesis of glutamate sits at a major intersection of cellular metabolism, linking carbon metabolism and nitrogen assimilation. In Bacillus subtilis, the only pathway for biosynthesis of glutamate in minimal medium uses as substrates the Krebs cycle intermediate, α-ketoglutarate, and glutamine, in a reaction catalyzed by glutamineoxoglutarate amidotransferase (GOGAT, also known as glutamate synthase) (Figure 1) 1. When cells of B. subtilis are grown in complex media, they can also obtain glutamate by aminotransferase reactions and by degradation of certain amino acids, e.g., arginine, ornithine and proline, via the Roc pathway 2. Glutamate, in addition to being a component of proteins, is the main nitrogen donor for the synthesis of many other amino acids and other nitrogen-containing compounds.

Figure 1.

Metabolic context of glutamate biosynthesis. Not all enzymes of the Krebs cycle and Roc pathway are indicated. Abbreviations: GS, glutamine synthetase, GOGAT, glutamate synthase, RocG, glutamate dehydrogenase, RocD, ornithine aminotransferase, CS, citrate synthase, ACN, aconitase, IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase, OGDH, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase.

Glutamate is the most abundant anion in the cell; its steady-state concentration in B. subtilis (100-200 mM) 3; 4; 5 demands that there be a high intracellular concentration of glutamate synthase or a high turnover number or both. However, the enzyme must also be subject to tight regulation, since its unrestricted activity could rapidly deplete valuable metabolites.

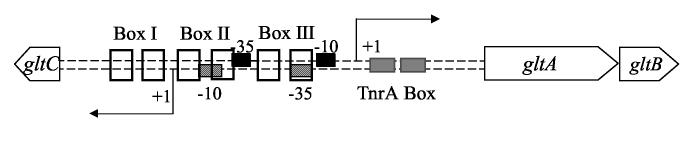

Glutamate synthase, a heterodimeric protein, is encoded by the gltA and gltB genes, which are organized as an operon (Figure 2) and whose expression is subject to nutritional regulation 1. Transcription of gltAB is high when cells are grown in glucose-ammonium medium, is reduced if glutamine is the nitrogen source or if glucose is replaced by poorly-metabolizable carbon sources 6, and is low when cells are grown in the presence of glutamate, ornithine, arginine or proline as sole nitrogen sources 7; 8. Repression in glucose-glutamate medium is mediated principally by the TnrA protein 9, a global regulator of many genes of nitrogen metabolism that is only active under conditions of nitrogen limitation 2; 10; 11. TnrA represses gltAB expression by binding to the promoter region of gltA (Figure 2) 9. Under conditions of nitrogen excess (i.e., the presence of glutamine or ammonium or a mixture of ammonium and sources of glutamate, such as arginine and ornithine), TnrA is inactivated by interaction with a complex of glutamine synthetase and glutamine 12 and repression of gltAB is relieved 9.

Figure 2.

The gltCAB locus. The −10 and −35 promoter elements of gltA (black boxes) and gltC (patterned boxes), as well as the dyad-symmetry elements important for GltC activity, Box I, Box II, and Box III, and the binding site of TnrA (TnrA Box) are indicated. The transcription start points are shown by bent arrows. The genes are not drawn to scale.

Even when TnrA is inactive, however, there is little expression of the gltAB operon unless GltC, a member of the LysR family of bacterial transcription factors, is active 13; 14; 15. The gltC gene is located upstream of and in divergent orientation to gltA (Figure 2). GltC activates transcription from the gltA promoter and is essential for cell growth in the absence of a source of glutamate in the medium 13; 14. GltC is also a negative autoregulator 13; 14. Genetic analysis has established that GltC activity requires interaction with two dyad-symmetry elements, Box I and Box II, located in the promoter regions of gltA and gltC (Figure 2). Box I is required both for repression of gltC and for activation of gltA; Box II is only required for the activation of gltA 13. The activities of most LysR-type proteins are modulated by interaction with low-molecular-weight effectors 15. GltC is likely to interact with such effectors as well, since mutants with constitutive GltC activity have been isolated, such as the mutant protein T99A 7; 16.

In previous work from our group, inhibition of gltAB expression by arginine and ornithine in a tnrA mutant was shown to be mediated through the effects of the amino acids on GltC activity 7. However, GltC does not respond to arginine or ornithine per se, but rather to their metabolism by the enzymes of the Roc pathway, leading to the suggestion that such metabolism produces positive or negative effectors of GltC activity (Figure 1) 7.

In the work reported here, we have studied the molecular mechanism of the regulation of gltAB by GltC. We have characterized the interaction of GltC with DNA and identified α-ketoglutarate, acting in competition with glutamate, as the co-activator of GltC and, hence, of glutamate biosynthesis.

Results

In vivo activity of His6-tagged GltC

GltC, as is the case for many other LysR-family proteins, is mostly insoluble when overexpressed in Escherichia coli. For this reason, it was necessary to use tagged versions of GltC to purify the soluble fraction of the protein efficiently. To test the functionality of His-tagged versions of the protein in vivo, the wild-type copy of gltC was substituted by the C-terminally His-tagged or N-terminally His-tagged versions of the gene, resulting in strains SP43 and SP51, respectively. These strains also carry a gltA-lacZ transcriptional fusion 9. Strain SP43 was phenotypically GltC+, i.e., able to grow in the absence of any source of glutamate, indicating that GltC-His6 was functional. However, while showing a wild-type level of β-galactosidase activity (gltA expression) in glucose medium containing ammonium (68 Miller units), SP43 cells had much higher β-galactosidase activity than did wild type cells when grown with ornithine plus ammonium (19.5 Miller units for SP43 versus 1.5 Miller units for the wild type). Thus, the C-terminal His-tag affected the ability of GltC to respond to ornithine. In other words, the C-terminal His-tag made GltC activity partially constitutive. This phenotype is reminiscent of that of previously isolated constitutive forms of GltC, e. g. GltC(T99A) 7; 16. Strain SP51, on the other hand, was unable to grow without a source of glutamate in the medium and did not express the gltA-lacZ fusion in medium with glutamate plus ammonium. Thus, the N-terminal His-tag made GltC inactive.

Purification of untagged GltC and its activity in vitro

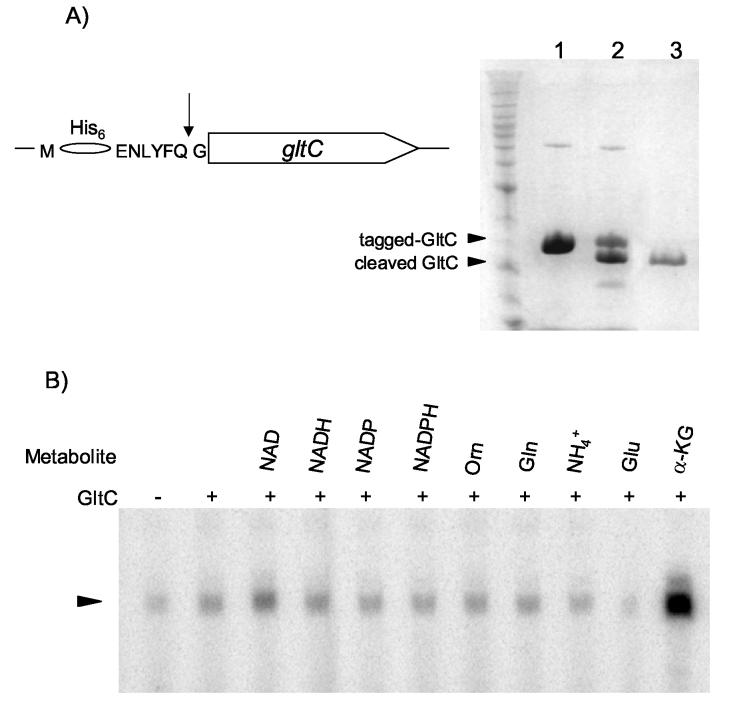

In order to eliminate the His-tag and purify an active and physiologically relevant form of GltC, a recognition site for the tobacco etch virus protease (TEVP) was introduced between the N-terminal His residues and the sequence of wild-type GltC or the constitutive mutant GltC(T99A) (Figure 3A). After induction in E. coli cells and purification of the proteins, the tagged wild-type and T99A GltC versions were subjected to digestion with TEVP. The resulting untagged proteins had an additional glycine residue at the N-terminus but were otherwise identical to the native GltC. For simplicity, these proteins will be designated as wild-type GltC and GltC(T99A), respectively.

Figure 3.

In vitro activity of GltC. Panel A: Purification of GltC. On the left: the N-terminal sequence of the modified version of gltC; the TEVP cleavage site is indicated by the arrow. On the right: SDS-PAGE of GltC purification. Lane 1. Uncleaved tagged GltC from E. coli. Lane 2. Tagged GltC treated with TEVP. Lane 3. GltC purified after cleavage. Panel B: In vitro transcription from the gltA promoter, using of B. subtilis RNAP, 500 nM GltC and the metabolites NAD (1 mM), NADH (0.2 mM), NADP (0.2 mM), NADPH (0.2 mM), ornithine (1 mM), glutamine (40 mM), NH4Cl (5 mM), glutamate (100 mM), or α-ketoglutarate (2 mM). The band corresponding to the gltA transcript is indicated with an arrow.

In a first attempt to test its activity, purified wild-type GltC (500 nM) was added to an in vitro transcription reaction in which a 300-bp DNA fragment that includes the promoter region of gltA served as a template for B. subtilis σA-RNA polymerase (RNAP) holoenzyme. Various potential positive or negative effectors were present at their physiological concentrations (Figure 3B). These putative effectors included all the substrates and products of glutamate synthase and glutamate dehydrogenase, the two enzymes dedicated to synthesis and degradation of glutamate (see Figure 1). The gltA transcript was detected as a product of about 101 nucleotides, corresponding to its expected size. Addition of GltC alone activated transcription of gltA in vitro, but only weakly (2-fold stimulation). In the presence of both GltC and 2 mM α-ketoglutarate, however, there was an additional 7-fold increase in gltA transcription. On the other hand, the presence of 100 mM glutamate reduced expression of gltA about 4-fold with respect to GltC alone, whereas the other metabolites tested had no significant effect on gltA transcription (Figure 3B).

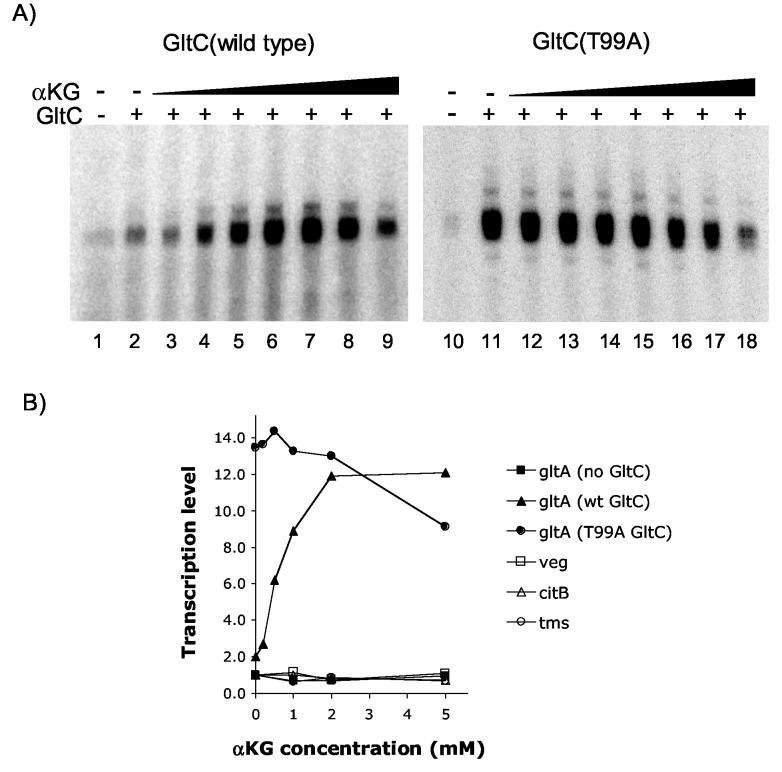

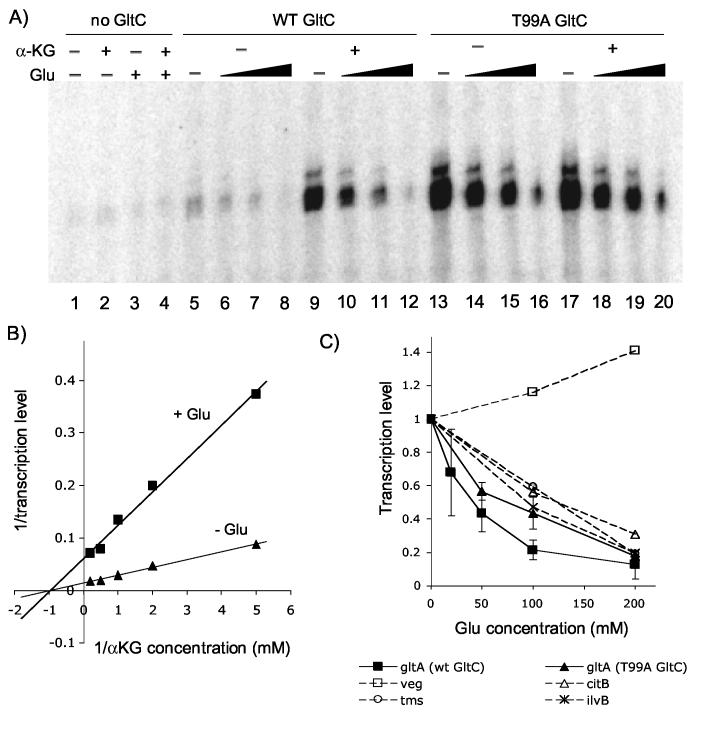

In order to determine the affinity of GltC for α-ketoglutarate, we performed in vitro transcription experiments in which increasing concentrations of the metabolite were added to the reaction. The maximum level of gltA transcription was obtained for 5 mM α-ketoglutarate (Figure 4A). When the inverse of the relative level of transcription was plotted versus the inverse of the concentration of α-ketoglutarate (i.e., a LineweaverBurk-type plot) (Figure 5B), the Km obtained was 1 mM, which is approximately the concentration of α-ketoglutarate found inside the cell 3. The expression from unrelated B. subtilis promoters, such as veg, citB and tms, as well as gltA in the absence of GltC, was not affected by the presence of α-ketoglutarate, indicating the specificity of its effect on GltC (Figure 4B). At high concentrations of α-ketoglutarate, there was an apparently non-specific, inhibitory effect on transcription (Figure 4A) that was also seen with the veg promoter (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of α-ketoglutarate on transcription. Panel A. In vitro transcription of gltA in the presence of 500 nM of GltC (wild-type or T99A), B. subtilis RNAP, and α-ketoglutarate in the concentration of 0.2 (lanes 3, 12), 0.5 (lanes 4, 13), 1 (lanes 5, 14), 2 (lanes 6, 15), 5 (lanes 7, 16), 10 (lanes 8, 17) or 20 (lanes 9, 18) mM. Panel B. Results of the in vitro transcription from the gltA promoter in the absence of GltC or in the presence of wild-type GltC or GltC(T99A) and from the veg, citB, and tms promoters in the presence of increasing concentrations of α-ketoglutarate.

Figure 5.

Effect of glutamate on B. subtilis RNAP-dependent gltA expression. Panel A: In vitro transcription experiment using B. subtilis RNAP, 500 nM GltC (wild-type or T99A) (as indicated), 2 mM α-ketoglutarate (as indicated) and glutamate at 50 mM (lanes 6, 10, 14, 18), 100 mM (lanes 3, 4, 7, 11, 15, 19) or 200 mM (lanes 8, 12, 16, 20). Panel B: Lineweaver-Burk plot of the relative transcription level of gltA versus α-ketoglutarate concentration in the absence and presence of 100 mM glutamate. Symbols: triangles, no glutamate; squares, with glutamate. Panel C: Graphic representation of the relative transcription level from the promoters indicated versus increasing concentrations of glutamate. For gltA, the mean of several experiments (from 3 to 6) performed in the presence of α-ketoglutarate for the wild-type GltC and with or without α-ketoglutarate for GltC(T99A) is shown.

The in vitro transcription level of the gltC gene was much lower than that of the divergent gltA gene even in the absence of GltC, the negative autoregulator 14. In the presence of GltC and α-ketoglutarate or glutamate, the gltC transcript completely disappeared (data not shown).

In vitro activity of mutant GltC protein

Previous work of our group had shown that the T99A mutant form of GltC is able to activate gltA expression to high level in vivo under all growth conditions, even in media containing arginine or ornithine 7; 16. We wanted to know whether this protein behaves constitutively (i.e., does not respond to effectors) in vitro with respect to gltA transcription. To do so, we tested the GltC(T99A)-dependent activation of gltA transcription without and with increasing concentrations of α-ketoglutarate (Figure 4A). There was no dependence of GltC(T99A) activity on α-ketoglutarate, and the amount of transcript obtained was similar to the maximum seen with wild-type GltC and α-ketoglutarate (See Figure 4B and Table 1). Interestingly, when lower concentrations of the protein were used (100-250 nM), we saw a slight stimulation of GltC(T99A) by α-ketoglutarate (data not shown).

Table 1.

| RNAP | GltC | Stimulation of gltA transcription by GltCa |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| − α-ketoglutarate | + α-ketoglutarate | ||

| wild type | 1.98 ± 0.05 (16) | 13.8 ± 0.2 (16) | |

| B. subtilis | |||

| T99A | 15.2 ± 1.4 (5) | 15.0 ± 0.9 (5) | |

| | |||

| wild type | 1.34 ± 0.06 (6) | 4.86 ± 0.18 (6) | |

| E. coli | |||

| T99A | 4.22 ± 0.37 (2) | 4.52 ± 0.34 (2) | |

The relative transcription values are given with respect to the transcription level in the absence of GltC. The mean ± the standard deviation of the mean are represented. The number of experiments is indicated in parentheses.

The fact that the constitutively active GltC did not require α-ketoglutarate to fully activate transcription of gltA supports the idea that α-ketoglutarate is a physiologically relevant co-activator of GltC.

Effect of glutamate on gltA transcription

As mentioned before, glutamate had a negative effect on gltA expression in the absence of α-ketoglutarate (Figure 3B). Because glutamate is the product of the glutamate synthase enzymatic reaction and α-ketoglutarate is a substrate of glutamate synthase, the two compounds may modulate GltC activity in concert. We performed in vitro transcription experiments in which GltC was incubated with and without α-ketoglutarate and with increasing concentrations of glutamate. Glutamate inhibited gltA transcription both in the absence and in the presence of α-ketoglutarate (Figure 5A, lanes 5-12); at 100 mM glutamate, inhibition of gltA transcription was 4-fold. Other potential effectors, such as ammonium and glutamine, had no inhibitory effect on α-ketoglutarate-stimulated transcription (data not shown). To further study the effect of glutamate on gltA expression, we performed in vitro transcription assays using increasing concentrations of α-ketoglutarate, with and without 100 mM glutamate. A plot of the inverse of the gltA transcription levels obtained as a function of the inverse of the concentration of α-ketoglutarate gave a pattern typical of non-competitive inhibition by glutamate, with respect to α-ketoglutarate (Figure 5B). In other words, glutamate seemed to act at a different site than did α-ketoglutarate, since glutamate did not modify the Km of GltC for α-ketoglutarate, but only the maximum level of expression.

GltC(T99A)-dependent gltA expression was also inhibited by glutamate, although to a lesser extent than was the wild-type protein (Figure 5A, lanes 14-16 without α-ketoglutarate and lanes 18-20 with α-ketoglutarate). This result suggested that the effect of glutamate on gltA transcription was due at least in part to a general inhibition of transcription. To address this point, we tested the effect of glutamate on several other B. subtilis promoters (Figure 5C). We observed a substantial inhibition of transcription from all the promoters except veg. While the inhibition pattern of gltA expression in the presence of GltC(T99A) was very similar to those for the ilvB, citB and tms promoters, the relative level of wild-type GltC-dependent gltA transcription in the presence of 100 mM glutamate was about 2-fold lower than that observed for the constitutive mutant, which suggested that there were both general effects of glutamate on most promoters and a specific effect of glutamate on gltA transcription mediated by wild-type GltC (Figure 5C). Although the sodium salt of glutamate was used for all the experiments described here, key results were replicated using potassium glutamate, a more physiologically relevant salt of glutamate (data not shown), indicating that transcription of many B. subtilis genes may be affected under conditions of drastic changes in the glutamate pool.

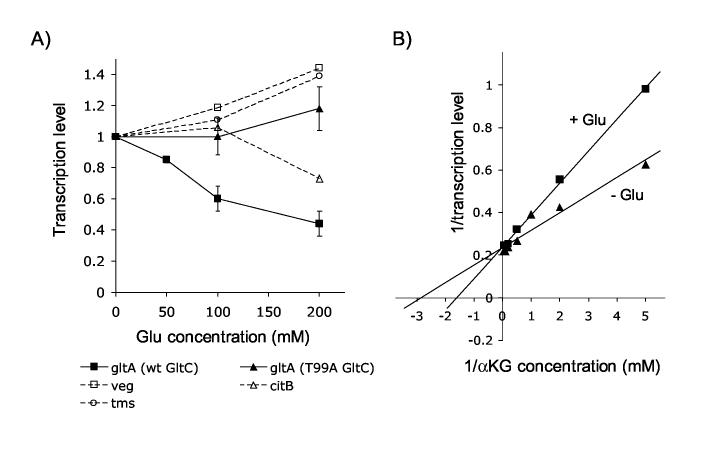

In vitro transcription of gltA using E. coli RNAP

For many B. subtilis promoters, including gltA, citB and tms, B. subtilis RNAP forms unstable open complexes, in contrast with E. coli RNAP, which forms stable complexes with most promoters 17 (and data not shown). However, at the veg promoter, the open complex is stable with both RNAPs 17. Because veg was the only promoter not inhibited by glutamate in our experiments, we wondered whether glutamate could be preferentially affecting transcription from unstable open complexes formed by B. subtilis RNAP at certain promoters, such as gltA, thereby masking an effect of glutamate on GltC.

To address this question we performed in vitro transcription experiments in the presence of increasing concentrations of glutamate with E. coli RNAP and the veg, citB, tms, or gltA promoters. Transcription from the veg, tms and citB promoters was not inhibited by 100 mM glutamate, as expected if glutamate affects preferentially unstable open complexes (Figure 6A). Only GltC-dependent transcription of gltA by E. coli RNAP was inhibited by glutamate (about 40% inhibition at 100 mM glutamate). GltC(T99A)-dependent gltA transcription, in contrast, was not affected by glutamate (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Effect of glutamate on E. coli RNAP-dependent transcription. Panel A: Graphic representation of the relative transcription level obtained using E. coli RNAP from the promoters indicated versus increasing concentrations of glutamate. For gltA, the mean of several experiments (from 2 to 4) performed in the presence of α-ketoglutarate for the wild-type GltC and with or without α-ketoglutarate for GltC(T99A) is shown. Panel B: The Lineweaver-Burk plot of the relative transcription level of gltA versus α-ketoglutarate concentration in the absence and presence of 100 mM glutamate using E. coli RNAP. Symbols: triangles, no glutamate; squares, with glutamate.

Basal transcription of gltA by E. coli RNAP was higher than it was with B. subtilis RNAP. Nevertheless, gltA transcription by E. coli RNAP was activated 5-fold by GltC, but only in the presence of α-ketoglutarate, as well as by GltC(T99A) both in the absence and in the presence of α-ketoglutarate (Table 1). In order to test whether glutamate competes with α-ketoglutarate for its effect on E. coli RNAP-dependent gltA transcription, we performed an in vitro transcription experiment using wild-type GltC and increasing concentrations of α-ketoglutarate with or without 100 mM glutamate. Surprisingly, in this case we obtained a Lineweaver-Burk-type plot corresponding to competitive inhibition by glutamate with respect to α-ketoglutarate (Figure 6B). The different concentrations of the effectors to which GltC responds (around 1 mM α-ketoglutarate and 100 mM glutamate) are consistent with the physiological pools of these metabolites in B. subtilis 3. We suggest that in the case of B. subtilis RNAP, glutamate inhibits GltC-dependent transcription of gltA by two mechanisms: (i) by inhibition of GltC by a mechanism that is competitive with respect to α-ketoglutarate, as is also seen in reactions catalyzed by E. coli RNAP, and (ii) by an additional non-specific inhibitory effect on B. subtilis RNAP common for all promoters that form unstable open complexes. Therefore, it seems that the effect of glutamate on B. subtilis RNAP was so pronounced that it masked the effect of glutamate on GltC (compare Figure 5B and 6B).

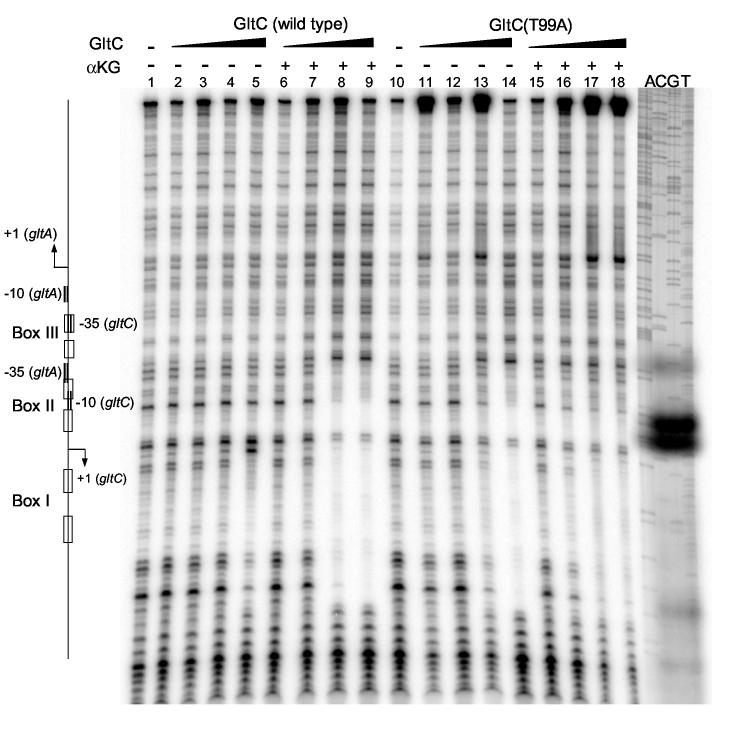

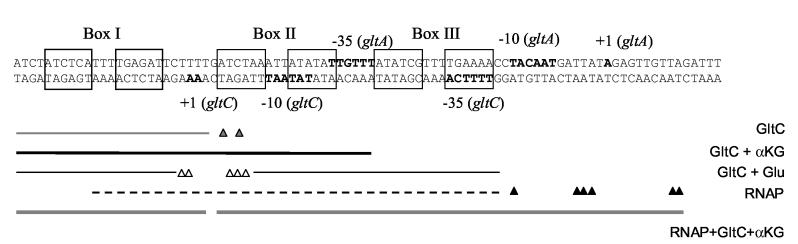

Binding of GltC to the gltCA promoter region

To map the sites of interaction between GltC and the gltCA promoter region, we performed DNase I footprinting analysis. A 209-bp DNA fragment containing the overlapping divergent promoters of the gltCA genes was end-labeled on one strand and incubated with increasing concentrations of GltC. Wild-type GltC by itself gave only weak protection of a region corresponding to the previously identified Box I (positions −75 to −53 with respect to the initiation start point of gltA) at 1 μM, the highest GltC concentration tested (Figure 7, lane 5). However, when 2 mM α-ketoglutarate was present, strong protection was observed at 0.5 and 1 μM GltC in an extended region (positions −75 to −31), corresponding to the binding of GltC to Box I, to the region previously identified as Box II and the −35 region of the gltA promoter (Figure 7, lanes 8, 9) (see Figure 8B). Therefore, α-ketoglutarate affected not only the extent of the protected region but also the affinity of GltC for Box I (about 2-fold increase). On the other hand, the constitutively active GltC(T99A) was able to bind to the same extended region even in the absence of the effector. However, α-ketoglutarate increased the affinity of GltC(T99A) for the DNA about 2-fold at low concentrations of the protein (Figure 7, lanes 11-14 and 15-16; Figure 8B).

Figure 7.

DNase I footprinting analysis of GltC binding to the gltCA regulatory region. Both the wild-type and T99A versions of GltC were used at the concentrations 0.125 (lanes 2, 6, 11, 15), 0.25 (lanes 3, 7, 12, 16), 0.5 (lanes 4, 8, 13, 17) or 1 (lanes 5, 9, 14, 18) μM. The binding was assayed in the absence (lanes 2-5 and 11-14) and in the presence (lanes 6-9 and 15-18) of 2 mM α-ketoglutarate. A scheme of the gltCA regulatory region is shown on the left (the relative sizes of the regulatory elements are slightly distorted in correspondence with the compression of the DNA bands). A DNA sequencing ladder obtained with plasmid pIPC10 as a template and primer oSP49 is shown on the right.

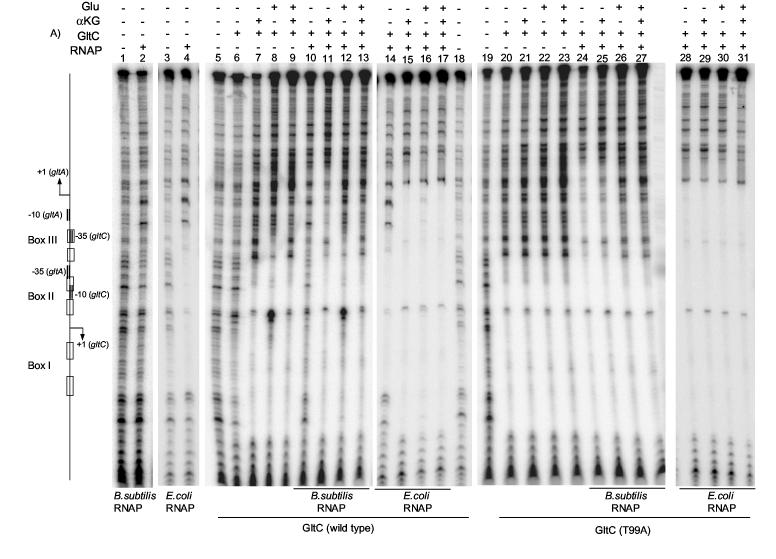

Figure 8.

DNase I footpringint analysis of GltC and RNAP binding to the gltCA regulatory region. Panel A. Binding of 1 μM of wild-type GltC (lanes 6-17) and GltC (T99A) (lanes 20-31) was assayed in combination with binding of 85 nM of B. subtilis RNAP (lanes 2, 10-13 and 24-27) or 0.5 unit of E. coli RNAP (lanes 4, 14-17 and 28-31). α-ketoglutarate and glutamate were added, when indicated, at a concentration of 2 mM and 100 mM, respectively. A scheme of the gltCA regulatory region is shown on the left (the relative sizes of the regulatory elements are slightly distorted in correspondence with the compression of the DNA bands). Panel B. The sequence of the gltCA regulatory region. The −10 and −35 promoter regions and transcription initiation sites of the gltC and gltA promoters are in bold. The regulatory elements Box I, Box II, and Box III are shown with open boxes. The different binding patterns found are shown below the sequence as following: thin grey line, the protected region by GltC alone; (grey triangles), hypersensitive bands obtained for GltC alone; thick black line, protection obtained for GltC in the presence of α-ketoglutarate; thin black line, the protected region by GltC plus glutamate; (open triangles), hypersensitive bands obtained for GltC plus glutamate; dotted black line, protected region obtained for RNAP alone; (black triangles), hypersensitive bands obtained for RNAP; thick grey line, protection obtained for RNAP plus GltC plus α-ketoglutarate.

Interestingly, we saw a very different pattern of protection when the binding of GltC was assayed in the presence of 100 mM glutamate (Figure 8A, lane 8). There was a protected region corresponding to Box I (positions −75 to −52), a hypersensitive region overlapping the first symmetry element of Box II (positions −53 to −42), suggesting a bend in the DNA, and a new protected region extending from the second symmetry element of Box II up to the −10 region of gltA (positions −44 to −14) (Figure 8B). The region corresponding to Box I was better protected in the presence of glutamate (Figure 8A, compare lane 8 to lane 6), indicating increased affinity of GltC for this region. The new protected region (located downstream of Box II with respect to the gltA promoter) corresponded to a previously identified dyad-symmetry element, Box III. This element has weak similarity to Box I and is located on the same face of the DNA helix as Box I and Box II. Mutations in the downstream half of Box III, which overlaps with the −35 region of the gltC promoter, greatly decreased gltC expression in vivo 13. However, mutation gltAp20, located in the upstream half of Box III, resulted in an 80% increase in expression from both the gltC and gltA promoters. The significance of Box III in gltA regulation has been unclear 13.

In the presence of both α-ketoglutarate (2 mM) and glutamate (100 mM), the protection pattern was more similar to that obtained for GltC in the presence of α-ketoglutarate alone than for GltC with glutamate alone (Figure 8B, lane 9, compare to lanes 7 and 8), suggesting that, at these concentrations of effectors, α-ketoglutarate affects GltC more strongly than does glutamate. The constitutively active GltC(T99A) was not affected by glutamate, showing a protected region similar to that for wild-type GltC in the presence of α-ketoglutarate (Figure 8A, lanes 20-23). The fact that only wild-type GltC was affected by glutamate with respect to binding to DNA supports the idea that glutamate is a bona fide effector of GltC.

Binding of RNAP to the gltCA promoter region

As mentioned above, it is known that B. subtilis RNAP forms less stable open complexes with most promoters than does E. coli RNAP 17. Accordingly, B. subtilis RNAP did not bind very efficiently to the gltCA promoter region, whereas E. coli RNAP showed a clear footprint. Nevertheless, the binding patterns of the two RNAPs were very similar, including a protected region around the gltC promoter (from positions −40 to +14 with respect to the gltC transcription start point, corresponding to positions −60 to −14 with respect to the gltA promoter) and some hypersensitive bands in the gltA promoter region, suggesting bending of the DNA in that region (Figure 8A, lane 2 for B. subtilis RNAP and lane 4 for E. coli RNAP) (see also Figure 8B). This pattern of interaction suggests that RNAP was binding primarily to the gltC promoter. The binding of B. subtilis RNAP to the gltCA promoter region was also tested using DNA fragments containing either a null mutation in the gltC promoter (gltCp18) 13 or a null mutation in the gltA promoter (gltAp40). gltAp40 is a TGAT to GATC substitution, partially overlapping the −10 region of the gltA promoter and inactivating the promoter in vivo (unpublished data). The footprint of B. subtilis RNAP at the DNA region containing the gltA null promoter region was identical to that found at the wild-type gltCA promoter region. On the other hand, a very faint footprint, if any, of B. subtilis RNAP was found in the case of the DNA region containing the gltC null promoter, indicating that the mutation substantially reduces the affinity of RNAP for the gltC-gltA intergenic region and confirming that binding of RNAP in the absence of GltC occurs only at the gltC promoter (data not shown).

No effect of α-ketoglutarate was observed on the binding of either RNAP to the gltCA promoter region (data not shown). In addition, no clear effect of glutamate on E. coli RNAP binding could be observed. However, even though the binding in general was poor, we could distinguish a reduction in the protection efficiency by B. subtilis RNAP after addition of 100 mM glutamate (data not shown).

Binding of RNAP to the gltA promoter in the presence of GltC

When we added B. subtilis RNAP plus wild-type GltC to the gltCA DNA, we obtained a protection pattern corresponding to the regions individually protected by both RNAP and GltC (Figure 8A, compare lane 10 to lanes 2 and 6), suggesting that, in footprinting analysis, GltC alone does not displace RNAP from the gltC promoter. When RNAP, GltC and 2 mM α-ketoglutarate were all present, there was an extended protected region (Figure 8A, lane 11) ranging from downstream of the transcription start point of gltC to downstream of the transcription start point of gltA (−75 to +10 of gltA promoter) (Figure 8B), indicating the binding of GltC to Box I and Box II and the binding of RNAP to the promoter region of gltA. The extended protection pattern was not affected by the null mutation in the gltC promoter, gltCp18, but was abolished by the null mutation in the gltA promoter, gltAp40. Thus, in the presence of GltC and α-ketoglutarate, RNAP acquires the ability to interact with the gltA promoter. Because the region protected by α-ketoglutarate-bound GltC (Box I and Box II) overlaps with the gltC promoter, it is difficult to know whether under these conditions RNAP can interact with the gltC promoter.

We also tested the binding of RNAP in the presence of GltC and glutamate (Figure 8A, lane 12). In this case, the protection pattern was similar to that obtained for GltC plus glutamate without RNAP, probably reflecting poor binding of RNAP both to the gltC and gltA promoters (Figure 8A, compare lane 12 to lane 8). On the other hand, when we added RNAP, GltC, α-ketoglutarate and glutamate to the reaction (Figure 8A, lane 13), we found an intermediate situation between the poor binding of RNAP in the presence of GltC plus glutamate, and the extended protection obtained for the binding of RNAP plus GltC and α-ketoglutarate (Figure 8A, compare lane 13 to lanes 11 and 12).

As noted above, the constitutively active GltC(T99A) showed the same protection pattern in the presence or absence of α-ketoglutarate or glutamate (Figure 8A, lanes 20-23), a pattern similar to that produced by wild-type GltC in the presence of α-ketoglutarate (Figure 8A, lane 7). The mixture of RNAP and GltC(T99A) gave the extended protection pattern characteristic of RNAP and wild-type GltC in the presence of α-ketoglutarate (Figure 8A, compare lanes 24 and 25 to lane 11), corresponding to the binding of RNAP to the gltA promoter region. When we added glutamate to the reaction (without or with α-ketoglutarate), along with GltC(T99A) and RNAP, we observed an intermediate situation between the protection seen for GltC(T99A) and the protection observed for GltC(T99A) plus RNAP, reflecting reduced binding of RNAP, probably due to the non-specific effect of glutamate on B. subtilis RNAP. In this case, the footprint was more balanced towards the extended protection pattern than it was with RNAP and wild-type GltC in the presence of α-ketoglutarate and glutamate (Figure 8A, compare lanes 26 and 27 to lane 13), as expected due to insensitivity of GltC (T99A) to the specific inhibitory effect of glutamate.

We also examined the footprints created by the simultaneous presence of E. coli RNAP and GltC. When wild-type GltC and E. coli RNAP were added to the reaction, we observed a footprint equivalent to the sum of the footprints obtained for RNAP alone and GltC alone (Figure 8A, lane 14, compare with lanes 4 and 5). Further addition of α-ketoglutarate revealed a fully protected region (−75 to +10 of gltA promoter) (Figure 8A, lane 15) identical to that obtained for B. subtilis RNAP plus GltC plus α-ketoglutarate, although there was stronger protection of the gltA promoter with E. coli RNAP (Figure 8A, compare line 15 to line 11). On the other hand, the effect of glutamate on binding of E. coli RNAP plus GltC was minimal (Figure 8A, lanes 16-17), as expected since the binding of E. coli RNAP itself to the DNA was not reduced by glutamate. Moreover, the region protected by RNAP overlaps with the binding of glutamate-bound GltC to Box I and Box III. In the case of GltC(T99A), neither α-ketoglutarate nor glutamate had any significant effect on binding of E. coli RNAP to DNA (Figure 8A, lanes 28-31) and the protection was complete because E. coli RNAP, in contrast to B. subtilis RNAP, is not sensitive to glutamate (Figure 8A, compare lanes 30-31 to 26-27).

Discussion

Interaction of GltC with its effectors and with DNA

We have shown here that GltC activity is regulated by a positive effector, α-ketoglutarate, and a negative effector, glutamate, apparently through direct binding. Most LysR-type proteins interact with a single low-molecular weight effector that is required for transcription activation. Only in a few cases have both positively-acting and negatively-acting effectors been described for the same protein 18; 19; 20.

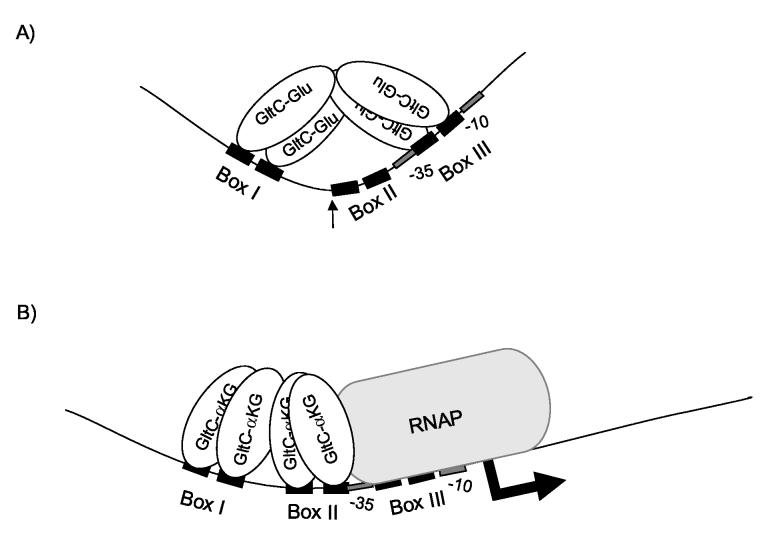

We have also described three modes of interaction of GltC with the gltA promoter region in vitro, presumably corresponding to three different conformational states of GltC. In the absence of effectors, GltC binds only to Box I, the primary binding site. When glutamate is present at its physiological concentration (100 mM) in vitro, GltC binds to both Box I and Box III and apparently induces a bend in the DNA. Several LysR-type proteins have been shown to operate as dimers of dimers 21; 22. If GltC behaves similarly, one dimer would be bound to Box I and a second dimer would be bound to Box III. In the presence of α-ketoglutarate alone or both α-ketoglutarate and glutamate, GltC molecules bind in vitro to Box I and Box II, instead of to Box I and Box III, and the DNA bend in this region is relaxed. Effector-dependent bending of DNA has been described for many LysR-type proteins 23; 24; 25; 26.

The re-positioning of GltC molecules from Box III to Box II that occurs in the presence of α-ketoglutarate is likely to be the crucial step for activation of gltA transcription. Positioning of α-ketoglutarate-bound GltC at Box II allows much more efficient binding of RNAP to the gltA promoter than does binding of GltC to Box I alone. This mode of positive regulation has been suggested for other LysR-type proteins 27; 28. GltC(T99A), a mutant form that activates gltA transcription constitutively in vivo, proved to activate transcription in vitro in an α-ketoglutarate-independent manner, indicating that the α-ketoglutarate-dependence we have discovered is physiologically relevant. Moreover, our results are in accord with our mutational analysis showing that the integrity of both Box I and Box II is required for transcriptional activation of gltA in vivo 13.

Two distinct groups of LysR-type proteins can be recognized, based on their patterns of effector-induced DNA binding in vitro. GltC has attributes in common with both groups. One type of LysR family members binds to a primary site (Box I in the case of GltC) in the absence of effectors and binds to a second site proximal to the promoter (Box II in case of GltC) only in the presence of an effector 15; 29; 30. For GltC, these states correspond to the unliganded and α-ketoglutarate-bound forms of the protein. A second group of LysR-type proteins binds to two sites (analogous to Box I and Box III in case of GltC) in the absence of the positive effector and, at least in some cases, represses transcription of the target gene. In the presence of the effector, the protein molecules bound to the promoter-proximal site (Box III in case of GltC) re-position themselves to a different site analogous to Box II in the case of GltC 25; 31; 32. A similar mode of binding is observed for GltC if we compare its glutamate-bound and α-ketoglutarate bound forms.

Though our previous in vivo results indicated that GltC is an activator of gltA transcription under all growth conditions tested 7; 13, the present in vitro results show that the glutamate-induced binding of GltC to Box III represses transcription, apparently due to interference with RNAP binding to the gltA promoter. Similar repressing activity was found for some other LysR-type proteins in the absence of their co-activators 26; 33; 34. Perhaps we have not yet found in vivo conditions that generate a sufficiently low ratio of α-ketoglutarate to glutamate to reveal this repressing activity of GltC. Interestingly, a mutation in Box III (the gltAp20 mutation) led to an 80% increase of gltA transcription under inducing conditions (growth in glucose-ammonium medium) 13 and a 3-fold increase in expression under repressing conditions (growth in glucose-ornithine medium) (unpublished results). Although we previously attributed such increases to an effect of the mutation on the intrinsic activity of the gltA promoter 13, the phenotype of the gltAp20 mutation might be indicative instead of impaired interaction of glutamate-bound GltC and Box III.

Whether the preference of glutamate-bound GltC for Box III versus Box II (Figure 9A) is a reflection of a specific glutamate-induced conformational state of GltC or unavailability of Box II or the bending angle of the DNA is unknown. Any such conformational change could affect the topology or the affinity of interaction or both. When α-ketoglutarate displaces glutamate, α-ketoglutarate-bound GltC dimers presumably undergo a conformational change that leads to the interaction with Box I and Box II, relief of DNA bending, and promotion of RNAP binding to the gltA promoter (Figure 9B). Insertion of a DNA sequence that separates Box I and Box II by almost one helical turn (e.g., the gltAp86 mutation) leads to high-level constitutive expression from the gltA promoter that is still GltC-dependent 7; 13. Based on our present results, we suggest that the increased distance between the two boxes allows access to Box II even for the glutamate-bound form of GltC and may make more difficult its binding to Box III. If so, the specific conformation of GltC induced by α-ketoglutarate is not obligatory for the interaction with RNAP.

Figure 9.

Model for the regulation of gltA expression by GltC. Panel A. Lower α-ketoglutarate to glutamate ratio. GltC is bound to Box I and Box III in a dimer-of-dimers fashion, which provokes a bending in the DNA (indicated with an arrow). The binding of GltC to Box III prevents the binding of the RNAP to the gltA promoter region resulting in very low expression of gltA. Panel B. Higher α-ketoglutarate to glutamate ratio. The DNA bending is relaxed and the second dimer of GltC is able to bind to Box II, which allows and promotes binding of RNAP to the gltA promoter region, resulting in high expression of gltA.

Our previous in vivo results had shown that GltC represses its own transcription under all growth conditions 9; 13. Surprisingly, in vitro results described here indicate that GltC alone is not able to repress gltC transcription. In the cell, however, GltC is likely to be bound to either α-ketoglutarate or glutamate (see below) and, under such conditions, gltC transcription is repressed by GltC in vitro. In accord with this interpretation, GltC(T99A) repressed gltC transcription in vitro in the absence of effectors (data not shown).

α-ketoglutarate pool in B. subtilis cells

Free GltC binds in vitro to Box I (albeit weakly), but we doubt that such binding has physiological significance. Even though α-ketoglutarate pools vary considerably, the intracellular concentration of glutamate (100-200 mM in minimal medium) 3; 4; 5 makes it unlikely that free GltC ever exists inside the cell. Our results suggest that the activity of GltC in B. subtilis cells is modulated by the ratio of the α-ketoglutarate and glutamate pools and the resultant proportion of α-ketoglurate-bound and glutamate-bound forms of the protein. Since the glutamate pool seems to be high in wild-type cells under most growth conditions, we suggest that GltC activity is determined mostly by variations in the α-ketoglutarate pool. Even though glutamate is much more abundant than α-ketoglutarate, it is a poor competitor with α-ketoglutarate for binding to GltC. Thus, as proposed previously 1; 6; 7, GltC primarily monitors the availability of α-ketoglutarate, a key carbon metabolite, but also detects glutamate, the key cellular nitrogen metabolite. The activity of TnrA, the second regulator of gltAB, is affected by the cell's ability to accumulate glutamine, a second critical nitrogen metabolite 10. Thus, GltC and TnrA together monitor both the substrates and the product of the glutamate synthase reaction, while controlling the synthesis of the enzyme that serves as a link between carbon and nitrogen metabolism. The activities of other regulators of nitrogen metabolism, such as the PII protein in E. coli and PII protein and NtcA in cyanobacteria, are known to be affected by α-ketoglutarate 35; 36.

In B. subtilis cells, the α-ketoglutarate pool is determined by a complex interplay among α-ketoglutarate-generating pathways (e.g., the tricarboxylic acid [TCA] branch of the Krebs cycle, glutamate dehydrogenase (RocG), and glutamate-dependent aminotransferase activities) and α-ketoglutarate-utilizing pathways (e.g., α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase of the Krebs cycle, α-ketoglutarate-dependent aminotransferase activities, and glutamate synthase itself). GltC activity and gltA transcription are high in glucose-ammonium medium 14; 16, perhaps due to the high pool of α-ketoglutarate provided by the reactions of the TCA branch enzymes, which are derepressed under such conditions 37; 38. GltC activity and gltA transcription are low in glucose-containing media that contain arginine or ornithine, i.e., substrates and inducers of the Roc catabolic pathway (Figure 1) 7. One of the first reactions of this pathway, catalyzed by ornithine aminotransferase (RocD), converts α-ketoglutarate to glutamate (Figure 1). We speculate that this reaction and repression of the TCA branch medium 39 (and our unpublished results) are the primary determinants of the low α-ketoglutarate pool in glucose-arginine medium. The last reaction of the Roc pathway, catalyzed by RocG, converts glutamate to α-ketoglutarate, but is repressed in glucose-containing media 40. When arginine or ornithine serves as the sole carbon and nitrogen source, however, gltA transcription still remains low 7, despite high activity of RocG. On the one hand, it is definitely in the cell's interest to prevent simultaneous activity of RocG and glutamate synthase, to avoid creating a futile cycle of synthesis and degradation of glutamate, consumption of glutamine and expenditure of ATP. But why doesn't the α-ketoglutarate produced by RocG activate GltC? When arginine or ornithine is the sole carbon source, the synthesis of nearly all cellular carbon compounds depends on conversion to α-ketoglutarate and subsequent metabolism through the Krebs cycle. Since under these conditions the synthesis of the TCA branch enzymes is repressed 39 (and our unpublished results), the consumption of α-ketoglutarate by α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase may be rapid enough to keep the pool low. In addition, reduction of the glutamate pool due to RocG activity may stimulate various α-ketoglutarate-dependent aminotransferases to generate glutamate at the expense of α-ketoglutarate.

Two previous results seem at first glance to be at odds with our conclusion that α-ketoglutarate is the primary modulator of GltC activity. First, when cells are grown in glucose-glutamine medium or glucose-ammonium-glutamate medium, conditions in which α-ketoglutarate production by both the TCA branch enzymes and RocG is repressed, gltAB expression is relatively high 8. In part, this level of expression is due to relief of repression by TnrA, but GltC must still be active for gltAB to be transcribed at the levels observed. We suggest that under such conditions excess glutamate is used to drive aminotransferase reactions that generate α-ketoglutarate.

Second, mutations that eliminate RocG activity relieve inhibition of gltAB transcription by arginine or ornithine 8; 9, even though such mutations would be expected to reduce the rate of α-ketoglutarate accumulation (Figure 1). In the absence of RocG, however, glutamate would accumulate and drive aminotransferase reactions toward α-ketoglutarate, replacing the RocG-dependent mode of α-ketoglutarate generation with another, perhaps more efficient mode that is dependent on multiple aminotransferases.

In summary, even though there are gaps in our knowledge about the size and flux in the α-ketoglutarate pool under various growth conditions and we cannot exclude the possibility that unknown factors affect GltC activity, the conclusion from in vitro studies that α-ketoglutarate is the primary determinant of GltC activity fits well with the results of in vivo analyses.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culture media

Bacillus subtilis strains were derived from strain SMY and were grown at 37 °C in TSS minimal medium 41 with 0.5% glucose as the carbon source and 0.2% nitrogen source or in DS nutrient broth medium. The same media with the addition of agar were used for growth of bacteria on plates. Escherichia coli strain DH5α 42 was used for plasmid constructions, and strain LMG194 (Δara714) was used to overexpress GltC 43 and to isolate plasmids for transformation of B. subtilis. L broth or L agar 44 was used for growth of E. coli strains. The following antibiotics were used when appropriate: chloramphenicol, 2.5 μg/ml or neomycin, 2.5-5 μg/ml, for B. subtilis strains; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml or kanamycin, 25 μg/ml, for E. coli strains.

DNA manipulations and transformation

Methods for plasmid isolation, agarose gel electrophoresis, use of restriction and DNA-modification enzymes, DNA ligation, and electroporation of E. coli cells were as described by Sambrook et al. (1989) 42. Isolation of chromosomal DNA and transformation of B. subtilis cells were as described 40. All cloned PCR-generated fragments were verified by sequencing.

Construction of B. subtilis strains expressing His-tagged versions of GltC

A DNA fragment corresponding to the 3′ two thirds of gltC with six histidine codons at the 3′ end was PCR amplified using B. subtilis chromosomal DNA as a template and oligonucleotides oSP24 (5′-CACGTCGAAGAATTCCTGCGCCAAGGCTCC-3′: the EcoRI site underlined) and oSP8 (5′-GTTCAGTCGACTTAATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGTTGATACTGCTCCAGC-3′: the SalI site underlined, the stop codon in italics and histidine codons in boldface) as forward and reverse primers, respectively. The 0.58-kb SalI/EcoRI DNA fragment of the PCR product was cloned in similarly digested pBB544 45, resulting in plasmid pSP12.

The introduction of six histidine codons at the 5′ end of gltC was done by overlapping PCR. The promoter region of gltC was PCR amplified using plasmid pIPC10 13 as a template and oligonucleotides oSP35 (5′-CCGGTCAGTCGACCTAACAACTC-3′: the SalI site underlined) and oSP34 (5′-GTGATGGTGATGGTGATGCATGTTTGTCTCACATCC-3′: histidine codons in boldface) as forward and reverse primers, respectively. A sequence corresponding to the 5′ two thirds of gltC was PCR amplified using plasmid pIPC10 as a template and primers oSP33 (5′-ATGCATCACCATCACCATCACGAGCTGCGCCAACTGCG-3′: histidine codons in boldface) (forward) and oSP36 (5′-CAAGCTCTAGATTTAATGGAACAAGCG-3′: the XbaI site underlined) (reverse). A third PCR was done using a mixture of the two PCR products described above as a template and oligonucleotides oSP35 and oSP36 as forward and reverse primers, respectively. The 0.65-kb SalI/XbaI DNA fragment generated from the final PCR product was cloned in similarly digested plasmid pBB544, resulting in plasmid pSP16.

Introduction of plasmids pSP12 and pSP16 in B. subtilis strain SMY yielded transformants due to single crossover homologous recombination in which the 3′-terminal or 5′-terminal part of gltC was substituted by its version encoding the His6-tag, resulting in strains SP41 and SP53, respectively. To construct strains SP43 and SP51, chromosomal DNA of strains SP41 and SP53, respectively, was used to transform strain LG219 (gltA-lacZ) 9. The presence of the His-codons at the 3′ or 5′ end of gltC in the chromosomal DNA of strains SP41 and SP43 or SP53 and SP51, respectively, was confirmed by PCR using a primer corresponding to these codons.

Overexpression and purification of GltC

gltC was PCR amplified using a template plasmids pIPC10 13 or pBB562 16 for the wild-type and T99A-modified versions of gltC, respectively, and oligonucleotides oSP30 (5′-GTCCAGTCGACGAAAACCTGTATTTCCAGGGTGAGCTGCGCCAACTGCG-3′: the AccI site underlined and the tobacco etch virus protease [TEVP] recognition sequence codons in boldface) and oSP31 (5′-GTTCATCTAGATTATTGATACTGCTCC-3′: the XbaI site underlined) as forward and reverse primers, respectively. The 0.9-kb AccI-XbaI fragments of the PCR products were cloned in pBB1272 (B. R. Belitsky, unpublished), which had been digested with ClaI (the AccI compatible enzyme) and XbaI, resulting in plasmids pSP14 (gltC+) and pSP25 (gltC[T99A]). Plasmid pBB1272 is a pBAD18 derivative, which contains the RBS of the B. subtilis citZ gene, initiation codon and six histidine codons followed by a ClaI site inserted downstream of the E. coli promoter Para. E. coli LMG194 (pSP14) and LMG194 (pSP25) were used to inoculate L broth containing amplicillin (100 μg/ml) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The culture was then diluted with fresh medium (1:100) and incubated at 25 °C until OD600 reached 0.3. Arabinose (0.05%) was added to induce expression of tagged GltC. The 1 l culture was incubated for an additional 4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5% (v/v) glycerol, and resuspended in 10 ml of the disruption buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 200 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% nonidet P-40, 1 mM PMSF). The cells were passed twice through a French press at 12,000 psi and were briefly sonicated. The soluble fraction was incubated with Talon (Co2+) beads (BD Biosciences). Beads with the bound GltC were washed twice with buffer II (500 mM KCl, 20 mM TrisHCl (pH 8), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole) and once with buffer IV (125 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole). Tagged GltC was eluted with buffer V (same as buffer IV but with 75 mM imidazole). All fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE (10%). After the purification, 600 μg of the protein was incubated with 100 units of the His-tagged TEVP (AcTEV™ Invitrogen) in a total volume of 1 ml (with the buffer indicated by the manufacturer) at room temperature for 12-14 h. The cleavage product was dialyzed against 1 l of buffer (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5% glycerol) for 2 h at 4 °C. The dialyzed protein was incubated with 300 μl of the Talon beads (equilibrated with the dialysis buffer) to absorb TEVP and uncleaved GltC. Untagged GltC was concentrated from the supernatant using Ultrafree-0.5 centrifugal filter units (Millipore). Figure 3A shows the results of the purification of cleavable tagged GltC from E. coli, digestion with TEVP and second purification to obtain untagged GltC.

In vitro transcription

Reactions were performed in a total volume of 10 μl in the transcription buffer: 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml of BSA with 4 units of RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), 150 μM ATP, CTP, and GTP, 20 μM UTP, 0.5 to 1 μCi of [α-32P]-UTP, and 30 nM of B. subtilis RNAP or 0.02-0.04 units of E. coli RNAP (Epicentre). His-tagged B. subtilis RNAP was purified from B. subtilis following the authors' instructions 46. A 300-bp PCR-generated fragment containing the gltCA regulatory' region (generated using pIPC10 13 as template for PCR and oBB13 [5′-CAGGACGGTAGAGACC-3′] and oSP17 [5′-CAATTTGTCTGCTGATTGC-3′] as forward and reverse primers, respectively) was used as a template for in vitro transcription at a concentration of 7.2 fmol/μl. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes and terminated by addition of 4 μl of the 20 mM EDTA, 95% formamide dye solution and immediate heating of the samples at 85 °C for five minutes. The samples were analyzed without further purification using 6% polyacrylamide-8 M urea DNA sequencing gels; the radioactive bands were detected and quantified using storage PhosphorImager screens, and the Image-Quant software (Molecular Dynamics). To confirm that the band obtained in these experiments corresponded to the gltA transcript, we used a template obtained as described above but using primer oBB4 (5′-CTACATTCCCTGATCTCG-3′) instead of oBB13. Other DNA fragments were generated by PCR as follows. For ilvB, plasmid pRPS5 as template and oRPS6 and oRPS7 as forward and reverse primers were used 47. For amplification of other promoters, B. subtilis chromosomal DNA was used as template and the following primers (forward and reverse, respectively) were used: for veg, oSP20 (5′-TGAGAATTGGTATGCC-3′) and oSP21 (5′-CAGAAGGGTACGTCTCAG-3′); for citB, oSP50 (5′-TGACCATCATTATCACCTC-3′) and oSP51 (5′-AACGTTTTTCTCGCTTGG-3′); and for tms, oSP52 (5′-GCAAGGACTGCTGAAAGG-3′) and oSP53 (5′-TCCACGACGTGCTCTACC-3′). The optimal concentrations of templates for the in vitro transcription experiments were determined experimentally and were as follows, veg: 0.4 fmol/μl, ilvB: 25 fmol/μl, citB: 8 fmol/μl, tms: 12 fmol/μl. α-ketoglutarate (sodium salt), sodium glutamate and other metabolites used in the experiments were from Sigma.

DNase I protection experiments

A 219-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the gltCA promoter region was amplified by PCR using oBB13 and oSP49 (5′-AAAATAACGCAGTTGGCG-3′) as forward and reverse primers, respectively, and DNA from pIPC10 13 as a template. One of the primers was radioactively labelled using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]-ATP.

For the experiments with GltC (Figure 7) or GltC plus E. coli RNAP (Figure 8A), the 32P-end-labeled gltCA promoter fragment was incubated with purified proteins in a total volume of 10 μl in 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml of BSA and the metabolites to be tested at 37 °C for 20 minutes (RNAP was added after 5 min pre-incubation). Five fmol of DNA (about 60,000 cpm) and 0.5 units of E. coli RNAP were used per assay.

For the experiments in which B. subtilis RNAP was present, 5 fmol of the labeled DNA fragment was incubated with proteins under conditions improving B. subtilis RNAP binding in a total volume of 25 μl in 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 20% glycerol, 0.25 mg/ml BSA, 200 μM dinucleotide UpA and 150 μM GTP for 20 minutes at 37 °C. A mix of 85 nM of RNAP and 3.2 μM of σA subunit (40-fold excess), added to improve RNAP binding, was incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes prior to use in the assay (the binding reaction was pre-incubated for 5 minutes before adding σA-saturated RNAP). σA subunit was purified from E. coli following the author's instructions 48. After the 20-min incubation, CaCl2 and MgCl2 were added to 10 mM final concentration and the DNA was subjected to digestion with 0.2-1 unit of RQ1 DNase I (Promega) for 1 min, followed by addition of 4 volumes of stop solution (12.5 mM EDTA, 0.125% SDS, 0.375 M sodium acetate). The reaction mixtures were extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and analyzed on 6% polyacrylamide-8 M urea sequencing gels. Dideoxy sequencing reactions were performed using a Sequenase Kit (U.S. Biochemical, Inc.) and [α-35S]-ATP.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research grant (GM036718) from the US Public Health Service and a postdoctoral fellowship to S. P. from the Ministry of Education and Science, Spain. S.P. is grateful to José Ángel Hernández for his helpful advice with protein purification.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Belitsky BR. Biosynthesis of amino acids of the glutamate and aspartate families, alanine and polyamines. In: Sonenshein AL, Hoch JA, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: From genes to cells. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 2002. pp. 203–231. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher SH, Débarbouillé M. Nitrogen source utilization and its regulation. In: Sonenshein AL, editor. Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives - from genes to cells. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher SH, Magasanik B. 2-ketoglutarate and the regulation of aconitase and histidase formation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1984;158:379–382. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.379-382.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu P, Leighton T, Ishkhanova G, Kustu S. Sensing of nitrogen limitation by Bacillus subtilis: comparison to enteric bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:5042–5050. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.5042-5050.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whatmore AM, Chudek JA, Reed RH. The effects of osmotic upshock on the intracellular solute pools of Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1990;136:2527–2535. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-12-2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wacker I, Ludwig H, Reif I, Blencke HM, Detsch C, Stulke J. The regulatory link between carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: regulation of the gltAB operon by the catabolite control protein CcpA. Microbiology. 2003;149:3001–3009. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. Modulation of activity of Bacillus subtilis regulatory proteins GltC and TnrA by glutamate dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:3399–3407. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3399-3407.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohannon DE, Rosenkrantz MS, Sonenshein AL. Regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamate synthase genes by the nitrogen source. J. Bacteriol. 1985;163:957–964. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.957-964.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belitsky BR, Wray LV, Jr., Fisher SH, Bohannon DE, Sonenshein AL. Role of TnrA in nitrogen source-dependent repression of Bacillus subtilis glutamate synthase gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:5939–5947. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.5939-5947.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wray LV, Jr., Ferson AE, Rohrer K, Fisher SH. TnrA, a transcription factor required for global nitrogen regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1996;93:8841–8845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida K, Yamaguchi H, Kinehara M, Ohki YH, Nakaura Y, Fujita Y. Identification of additional TnrA-regulated genes of Bacillus subtilis associated with a TnrA box. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:157–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wray LV, Jr., Zalieckas JM, Fisher SH. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase controls gene expression through a protein-protein interaction with transcription factor TnrA. Cell. 2001;107:427–435. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belitsky BR, Janssen PJ, Sonenshein AL. Sites required for GltC-dependent regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamate synthase expression. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:5686–5695. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5686-5695.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohannon DE, Sonenshein AL. Positive regulation of glutamate biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:4718–4727. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4718-4727.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schell MA. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1993;47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. Mutations in GltC that increase Bacillus subtilis gltA expression. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:5696–5700. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5696-5700.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whipple FW, Sonenshein AL. Mechanism of initiation of transcription by Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase at several promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;223:399–414. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90660-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firmin J, Wilson K, Rossen L, Johnston A. Flavonoid activation of nodulation genes in Rhizobium reversed by other compounds present in plants. Nature. 1986;324:90–102. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs C, Frere JM, Normark S. Cytosolic intermediates for cell wall biosynthesis and degradation control inducible beta-lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Cell. 1997;88:823–832. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81928-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrowski J, Kredich NM. In vitro interactions of CysB protein with the cysJIH promoter of Salmonella typhimurium: inhibitory effects of sulfide. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:779–785. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.779-785.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muraoka S, Okumura R, Ogawa N, Nonaka T, Miyashita K, Senda T. Crystal structure of a full-length LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CbnR: unusual combination of two subunit forms and molecular bases for causing and changing DNA bend. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:555–566. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smirnova IA, Dian C, Leonard GA, McSweeney S, Birse D, Brzezinski P. Development of a bacterial biosensor for nitrotoluenes: the crystal structure of the transcriptional regulator DntR. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher RF, Long SR. Interactions of NodD at the nod Box: NodD binds to two distinct sites on the same face of the helix and induces a bend in the DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;233:336–348. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hryniewicz MM, Kredich NM. Stoichiometry of binding of CysB to the cysJIH, cysK, and cysP promoter regions of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:3673–3682. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3673-3682.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toledano MB, Kullik I, Trinh F, Baird PT, Schneider TD, Storz G. Redox-dependent shift of OxyR-DNA contacts along an extended DNA-binding site: a mechanism for differential promoter selection. Cell. 1994;78:897–909. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Helmann JD, Winans SC. The A. tumefaciens transcriptional activator OccR causes a bend at a target promoter, which is partially relaxed by a plant tumor metabolite. Cell. 1992;69:659–667. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lochowska A, Iwanicka-Nowicka R, Zaim J, Witkowska-Zimny M, Bolewska K, Hryniewicz MM. Identification of activating region (AR) of Escherichia coli LysR-type transcription factor CysB and CysB contact site on RNA polymerase alpha subunit at the cysP promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:791–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao K, Fujita N, Ishihama A. Involvement of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit C-terminal region in co-operative interaction and transcriptional activation with OxyR protein. Mol. Microbiol. 1993;7:859–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang M, Crawford IP. The roles of indoleglycerol phosphate and the TrpI protein in the expression of trpBA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:979–988. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang JZ, Schell MA. In vivo interactions of the NahR transcriptional activator with its target sequences. Inducer-mediated changes resulting in transcription activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:10830–10838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Keulen G, Ridder AN, Dijkhuizen L, Meijer WG. Analysis of DNA binding and transcriptional activation by the LysR-type transcriptional regulator CbbR of Xanthobacter flavus. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:1245–1252. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1245-1252.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Winans SC. The sixty nucleotide OccR operator contains a subsite essential and sufficient for OccR binding and a second subsite required for ligand-responsive DNA bending. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;253:691–702. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindquist S, Lindberg F, Normark S. Binding of the Citrobacter freundii AmpR regulator to a single DNA site provides both autoregulation and activation of the inducible ampC beta-lactamase gene. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:3746–3753. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3746-3753.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McFall SM, Chugani SA, Chakrabarty AM. Transcriptional activation of the catechol and chlorocatechol operons: variations on a theme. Gene. 1998;223:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrero A, Muro-Pastor AM, Valladares A, Flores E. Cellular differentiation and the NtcA transcription factor in filamentous cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004;28:469–487. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reitzer L. Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;57:155–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin S, Sonenshein AL. Transcriptional regulation of Bacillus subtilis citrate synthase genes. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:4680–4690. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4680-4690.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenkrantz MS, Dingman DW, Sonenshein AL. Bacillus subtilis citB gene is regulated synergistically by glucose and glutamine. J. Bacteriol. 1985;164:155–164. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.155-164.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blencke HM, Reif I, Commichau FM, Detsch C, Wacker I, Ludwig H, Stulke J. Regulation of citB expression in Bacillus subtilis: integration of multiple metabolic signals in the citrate pool and by the general nitrogen regulatory system. Arch. Microbiol. 2006;185:136–146. doi: 10.1007/s00203-005-0078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. Role and regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamate dehydrogenase genes. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:6298–6305. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6298-6305.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fouet A, Sonenshein AL. A target for carbon source-dependent negative regulation of the citB promoter of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:835–844. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.835-844.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y.: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belitsky BR, Gustafsson MC, Sonenshein AL, Von Wachenfeldt C. An lrp-like gene of Bacillus subtilis involved in branched-chain amino acid transport. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:5448–5457. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5448-5457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qi Y, Hulett FM. PhoP-P and RNA polymerase sigmaA holoenzyme are sufficient for transcription of Pho regulon promoters in Bacillus subtilis: PhoP-P activator sites within the coding region stimulate transcription in vitro. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;28:1187–1197. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shivers RP, Sonenshein AL. Activation of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY by direct interaction with branched-chain amino acids. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:599–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helmann JD. Purification of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase and associated factors. Methods Enzymol. 2003;370:10–24. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]