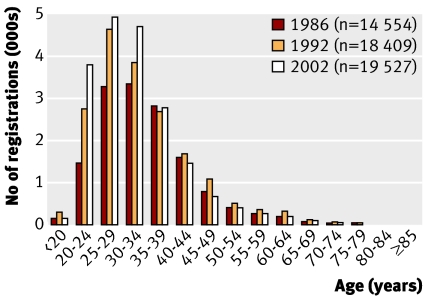

There may be several reasons why cervical screening coverage in young women has fallen yet again, including problems with access to appointments with general practitioners, but the new policy not to screen women aged 20-24 can hardly have helped.1 It was announced with the message that screening that age group caused more harm than good, which is unlikely to encourage them to accept their invitations from age 25. Prevalence of carcinoma in situ (CIN3) has increased in women aged 20-24 (figure), which is consistent with more women in recent birth cohorts starting sexual activity in their mid-teens.

Registrations of carcinoma in situ (CIN3), England (source www.statistics.gov.uk)

The new policy will add more than 3000 women with untreated CIN3 to the larger numbers failing to accept their invitations later on. We accept that any degree of CIN may regress, invasive cervical cancer (ICC) is rare in women under 25, and screening does little to reduce its incidence in such young women. However, ICC can develop within a couple of years of missed high-grade cytology, failure to investigate cytological abnormalities, or incomplete treatment,2 emphasising the importance of treating high-grade CIN when it is found.

Screening in the UK has been highly successful since it was centrally organised in 1988: incidence and mortality have fallen by more than 40% despiteincreased risk of disease.3 This has been achieved by treating high-grade CIN, particularly CIN3, in young women. The peak prevalence of CIN3 is in women aged 25-29 amongst whom the fall in coverage has been greatest.

ICC is more difficult to prevent in young women because there are less screening opportunities to treat these lesions before they become invasive.4 The peak incidence of ICC in the screening age groups is now in women aged 35-39. Most of these cancers are detected by screening at an early and treatable stage.4

Decisions about treatment of CIN should be based on a balance between risk of progression, likelihood of regression and risk of treatment.5 Women should be informed about the risk of high-grade CIN, its greater frequency in young women, the importance of surveillance of low grade abnormalities and the fact that an epidemic of cervical cancer has been prevented by screening women when they were young.2 General practitioners and clinics should not be prevented from screening women whom they believe to be at risk if those women themselves want to be screened.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.News. In brief. Women attend fewer smear tests. BMJ 2007;334:172. (27 January.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janerich DT, Hadjimichael O, Schwartz PE, et al. The screening histories of women with invasive cancers, Connecticut. Am J Public Health 1995;85:791-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peto J, Gilham C, Fletcher O, Matthews FE. The cervical cancer epidemic that screening has prevented in the UK. Lancet 2004;364:249-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbert A. Screening young women: how soon should we start? HPV Forum (in press).

- 5.Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirch P, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis W. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2006;367:489-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]