Abstract

The anaphase-promoting complex (APC) early mitotic inhibitor 1 (Emi1) is required to induce S- and M-phase entries by stimulating the accumulation of cyclin A and cyclin B through APCCdh1/cdc20 inhibition. In this report, we show that Emi1 proteolysis can be induced by cyclin A/cdk (cdk for cyclin-dependent kinase). Paradoxically, Emi1 is stable during G2 phase, when cyclin A/cdk, Plx1 and SCFβtrcp (SCF for Skp1-Cul1-Fbox protein)—which play a role in its degradation—are active. Here, we identify Pin1 as a new regulator of Emi1 that induces Emi1 stabilization by preventing its association with SCFβtrcp. We show that Pin1 binds to Emi1 and prevents its association with βtrcp in an isomerization-dependent pathway. We also show that Emi1–Pin1 binding is present in vivo in XL2 cells during G2 phase and that this association protects Emi1 from being degraded during this phase of the cell cycle. We propose that S- and M-phase entries are mediated by the accumulation of cyclin A and cyclin B through a Pin1-dependent stabilization of Emi1 during G2.

Keywords: Emi1, Pin1, SCFβtrcp , degradation, cell cycle

Introduction

Events controlling cell division are governed by the degradation of different regulatory proteins by the anaphase-promoting complex (APC), a multisubunit ubiquitin ligase that induces the ordered ubiquitin-dependent destruction of mitotic regulators. The correct timing of activation of APC is modulated by the sequential binding of APC with different activators and inhibitors (for a review see Castro et al, 2005). One of these inhibitors is the early mitotic inhibitor 1 (Emi1). At the G1–S transition, the Emi1 gene is transcriptionally stimulated by the E2F transcription factor, resulting in an increase in Emi1 levels. These high levels of Emi1, which persist through S and G2 phase, first promote inhibition of APC-Cdc20 homologue 1 and subsequently the inhibition of APC-cell division cycle mutant 20 (Cdc20), allowing cyclin A and cyclin B accumulation (Hsu et al, 2002). Most Emi1 is destroyed at prometaphase, before cyclin A degradation, allowing APC-Cdc20 activation and the completion of mitosis. Emi1 proteolysis is mediated by phosphorylation through at least two different kinases: cyclin B/cdk1 and Plx1. Cyclin B/cdk1 phosphorylates the five different pSer/Thr-Pro consensus sites, whereas Plx1 phosphorylates on its D-S-G-XX-S domain. Both phosphorylations collaborate to promote Emi1 binding to βtrcp and subsequent SCFβtrcp-dependent degradation (Margottin-Goguet et al, 2003; Hansen et al, 2004). At prometaphase, the majority of Emi1 protein is degraded; however, paradoxically, a fraction of this protein remains stable at the spindle poles (Hansen et al, 2004).

Pin1 is a peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase that isomerizes phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro peptide bonds (Lu et al, 1996). Pin1-catalysed isomerization modulates the conformation of the substrate, thereby affecting different cell functions through the regulation of enzymatic activity, protein stability or protein–protein interaction (Lu et al, 2002; Joseph et al, 2003; van Drogen et al, 2006). In this report, we show that Pin1 stabilizes Emi1 by inhibiting Emi1 binding to βtrcp and that this stabilization is dependent on the isomerization activity of Pin1. This pathway would prevent a rapid degradation of Emi1 soon after cyclin A–cyclin B/cdk activation, ensuring the correct proteolysis of Emi1 once sufficient levels of these two cyclins are present in the cells.

Results

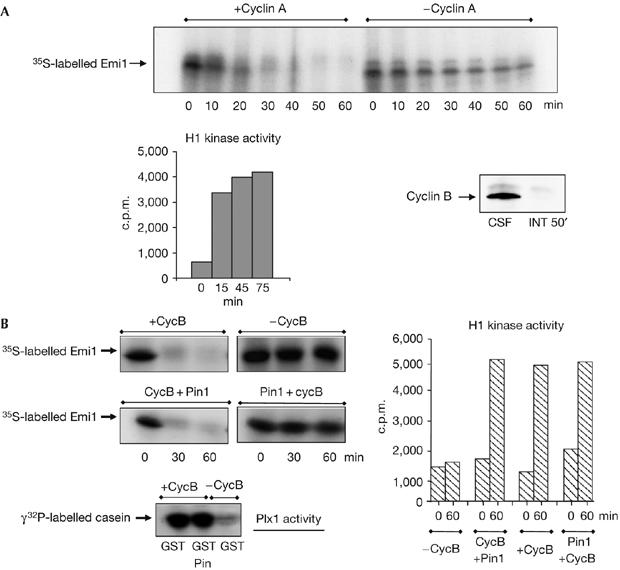

Cyclin A/cdk promotes Emi1 degradation

We cloned Xenopus Emi1 complementary DNA and raised a polyclonal antibody against the glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged full-length Emi1 protein (supplementary Fig S1 online). Emi1 contains five Ser/Thr-Pro sites and phosphorylation of these motifs by cyclin B/cdk1 has been described as a prerequisite for Emi1 to be proteolysed; however, the exact contribution of each Ser/Thr-Pro site to the degradation of this protein is not known (Reimann et al, 2001). We analysed the exact role of each of these sites by using the corresponding mutants. Our results show that Emi1 degradation is mainly induced by phosphorylation on Ser 29 and Thr 122 (supplementary Fig S2 online). In this regard, it is known that, in addition to cyclin B/cdk1, cyclin A/cdk1/2 can also phosphorylate pSer/Thr-Pro consensus sites. Thus, we then analysed whether cyclin A/cdk could also phosphorylate these sites and promote Emi1 proteolysis. To test this hypothesis, we used Xenopus interphase egg extracts obtained 50 min after ionophore activation; the extracts lacked cyclin B and cyclin A as a result of treatment with cycloheximide. As shown in Fig 1A, the addition of cyclin A induced activation of cyclin A/cdk and degradation of Emi1, indicating that, in vitro, both cyclin B/cdk1 and cyclin A/cdk can induce Emi1 proteolysis. However, Emi1 is stable during G2 in the presence of active cyclin A/cdk complex (Margottin-Goguet et al, 2003; Hansen et al, 2004), leading to the question of why Emi1 protein is not degraded during this phase of the cell cycle when cyclin A/cdk, and also the Plx1 kinase and SCFβtrcp complexes, seem to be active. We hypothesize that this protein could be protected from being proteolysed under these conditions.

Figure 1.

Pin1 stabilizes Emi1 in vitro. (A) Cyclin A/cdk promotes Emi1 degradation in interphase egg extracts. Human recombinant cyclin A (1.2 ng/μl) was added to interphase egg extracts devoid of endogenous cyclin A and cyclin B by the addition of cycloheximide (INT 50′). After 15 min, radiolabelled Emi1 was added and samples were taken at the indicated time points to analyse the 35S-labelled Emi1 levels and H1 kinase activity. A sample of 2 μl of a metaphase II-arrested extract (CSF) and the INT 50′ extract was immunoblotted with cyclin B2 antibody. (B) Pin1 stabilizes Emi1 in mitotic extracts. Interphase egg extracts were divided into four groups. One of these groups was not supplemented (−CycB). The second group was supplemented with recombinant GST-cyclin B (+CycB) only. The third group was first supplemented with GST–cyclin B and 15 min later with GST–Pin1 (CycB+Pin1). Finally, radiolabelled Emi1 was added in these three groups. In the fourth group, GST–Pin1 and radiolabelled Emi1 were simultaneously added and 15 min later GST–cyclin B was also added (Pin1+cycB). At the indicated time points after the addition of Emi1, samples of 2.8, 1 and 10 μl were taken to analyse the 35S-labelled Emi1 levels, H1 kinase activity and Polo kinase (Plx1) activity. Time 0 of the H1 kinase activity corresponds to the time at which Emi1 protein was added to the extract. Time 0 in the degradation assays corresponds to the time at which all the components of the mixture were present in the extract. cdk, cyclin dependent kinase; Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor 1; GST, glutathione S-transferase; Pin1, protein interacting with NIMA1.

Pin1 stabilizes Emi1 in mitotic extracts

Considering that Emi1 degradation is mediated by phosphorylation of the 29 and 122 Ser/Thr-Pro motifs, we hypothesized that endogenous Emi1 could be protected from being proteolysed during G2 by Pin1 (Lu et al, 1996). To test this hypothesis, Emi1 degradation was induced in extracts from interphase Xenopus eggs (interphase extracts) by the addition of cyclin B. These extracts were divided into four groups. In the first group, no GST–cyclin B was added, whereas the second group contained only GST–cyclin B. In the third group, GST–cyclin B was added 15 min before GST–Pin1. Finally, these three groups were supplemented with radiolabelled wild-type Emi1. In the last group, we added GST–Pin1 simultaneously with radioalabelled Emi1 and, 15 min later, GST–cyclin B (Fig 1B). As expected, Emi1 was not degraded in the absence of GST–cyclin B (−CycB); however, the addition of this cyclin alone induced the complete disappearance of Emi1 (+CycB). Similarly, we observed Emi1 degradation when Pin1 was added 15 min after GST–cyclin B (CycB+Pin1). By contrast, its proteolysis was completely blocked when Pin1 was added 15 min before cyclin B (Pin1+CycB). This was not the result of inhibition of cyclin B/cdk1 activation, as no difference in the activity of Plx1 or cyclin B/cdk1 was observed when Pin1 was introduced before or after the addition of GST–cyclin B. These results indicate that Pin1 can block Emi1 proteolysis only if it is present before the activation of cyclin B/cdk1.

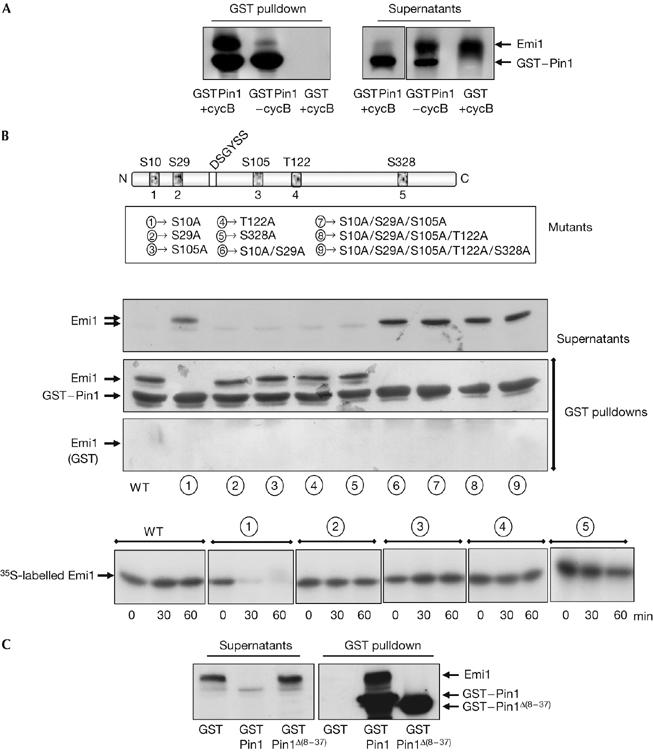

Next, we examined whether Emi1 associates with Pin1. As shown in Fig 2A, we did not detect Emi1 in the GST pulldown material when only GST–cyclin B was added to the extracts in the absence of GST–Pin1 (GST+cycB), indicating that Emi1 does not bind to GST–cyclin B. Similarly, only a residual amount of Emi1 was bound to Pin1 in the absence of cyclin B/cdk1 activity (GSTPin1−cycB), whereas most Emi1 was associated with Pin1 when cyclin B/cdk1 was activated by the addition of GST–cyclin B (GSTPin1+cycB).

Figure 2.

Emi1 binding to Pin1 depends on the phosphorylation of Ser 10 of Emi1 and on the WW domain of Pin1. (A) Emi1-translated interphase egg extracts were supplemented with the proteasome inhibitor 4 hydroxy-5iodo-3-nitro-phenylacetyl-leucine-leucine vinylsulphone and with sepharose beads coupled to either GST–Pin1 (GSTPin1) or GST (GST) proteins. Thirty minutes later, GST–cyclin B was added (+cycB) or not (−cycB) to the mix and incubated for an additional 30 min. Finally, a GST pulldown was carried out. The precipitated samples and 1 μl of supernatants were analysed by western blot sequentially with an Emi1 antibody and a Pin1 antibody. (B) Five point mutants corresponding to the five putative cyclin B/cdk1 phosphorylation sites and double, triple, quadruple and quintuple mutants were constructed and their binding to GST–Pin1 or, as a control, to GST was analysed in the presence of GST–cyclin B by GST pulldown analysis, as described in (A). Degradation of simple mutants was analysed in interphase egg extract supplemented with wild-type GST–Pin1 and GST–cycB as described in Fig 1B. (C) GST pulldown analyses were developed as described in (A), in the presence of GST–cyclin B and of either wild-type GST–Pin1 (GST–Pin1) or GST–Pin1 deleted of the WW domain (GST–Pin1Δ(8–37)). cdk, cyclin dependent kinase; Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor 1; GST, glutathione S-transferase; Pin1, protein interacting with NIMA1; WT, wild type.

These results indicate that Emi1 is stabilized by Pin1 if there is pre-incubation of these two proteins followed by phosphorylation of the complex by cyclin B/cdk1. This phosphorylation could be required to stabilize Emi1–Pin1 binding. We propose that Emi1 is protected from proteolysis only when it is stably complexed with Pin1. This stable association would implicate the binding of Pin1 to two different sites of Emi1 and would be achieved in a two-step process. First, Pin1 would unstably bind to Emi1 in a non-pSer/Thr-Pro site; second, cyclin B/cdk1 would phosphorylate Emi1 and promote the stable binding of Pin1 to its canonical pSer/Thr-Pro site of Emi1. Thus, phosphorylation of Emi1 by cyclin B/cdk1 would promote either stabilization of Emi1 when it is pre-associated with Pin1, or Emi1 degradation in the absence of Pin1, or when this isomerase is present after cyclin B/cdk1 activation.

Requirements for Emi1 binding to Pin1

To determine whether the Ser/Thr motifs of Emi1 participate in Pin1 binding, we used the five Ser/Thr to Ala simple mutants of Emi1 and the double, triple, quadruple and quintuple mutants (Fig 2B). As depicted in Fig 2B, all single mutants bound to GST–Pin1 except for S10A. Moreover, we did not observe Pin1 binding to Emi1 in the double, triple, quadruple or quintuple mutants, in which Ser 10 was also mutated to Ala. These results indicate that Pin1 binding to Emi1 depends on the phosphorylated Ser 10-Pro motif. If this is the case, the S10A mutant might be degraded in the presence of Pin1. As expected, the S10A mutant was rapidly proteolysed when GST–Pin1 was added (Fig 2B, lower panel). As it is known that Pin1 binds and isomerizes phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro motifs (Yaffe et al, 1997; Lu et al, 2002; Wulf et al, 2005), our results indicate that Pin1 directly binds and isomerizes Emi1 protein. Moreover, the fact that only the S10A mutant is degraded in the presence of Pin1 indicates that Ser 10 could be the binding site and also the putative isomerization site of Emi1.

Next, we tested whether Pin1 binding to Emi1 depends on the WW domain of Pin1. We constructed a Pin1 mutant in which the WW motif was deleted (Δ(8–37)) and then examined the capacity of this mutant to bind to Emi1. As shown in Fig 2C, the Δ(8–37) mutant completely lost its binding to Emi1. Although we cannot exclude the possibility of a misfolding of the deleted WW form of Pin1, it is likely that this domain is responsible for Pin1 binding to Emi1.

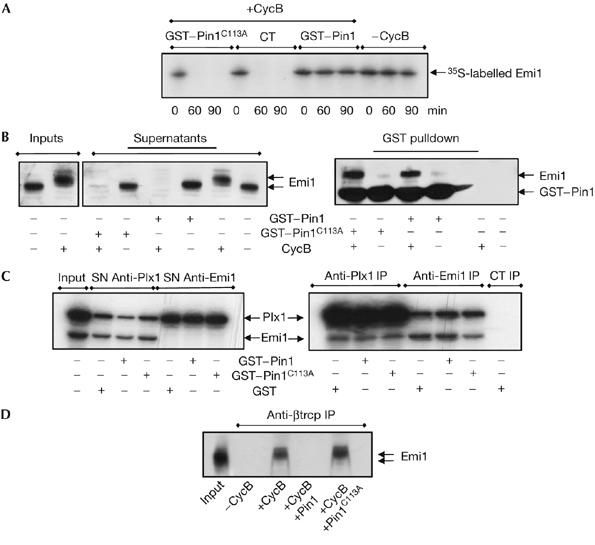

Emi1 isomerization prevents Emi1–βtrcp association

To examine whether the isomerase activity of Pin1 is also required to induce Emi1 stabilization, we used a Pin1 mutant (Pin1C113A) that fails to isomerize pSer/Thr-Pro bonds (Winkler et al, 2000). When interphase egg extracts were supplemented with Pin1C113A and Emi1 before the addition of cyclin B, we observed a rapid degradation of Emi1 with kinetics similar to that observed in extracts in which only cyclin B was added (Fig 3A). As expected, extracts supplemented with both wild-type Pin1 and cyclin B, and extracts lacking both Pin1 and cyclin B, presented a stable level of Emi1 protein throughout the experiment. The lack of Emi1 stabilization in the presence of the Pin1 isomerization mutant was not the result of a loss of Emi1/Pin1 association, as both proteins bound Emi1 with a similar efficiency (Fig 3B).

Figure 3.

Pin1-dependent isomerization mediates stabilization of Emi1 by preventing its association with SCFβtrcp. (A) Interphase egg extracts were supplemented with either GST–Pin1 or the GST–Pin1C113A mutant and radiolabelled Emi1. After 15 min, GST–cyclin B was added. At the indicated time points, a sample was removed and analysed by autoradiography to measure levels of Emi1. (B) GST pulldowns were developed as described in Fig 2A except for the addition of either the wild-type (GST–Pin1) or the mutated (GST–Pin1C113A) proteins. Samples were analysed by western blot sequentially with an Emi1 antibody and subsequently a Pin1 antibody. (C) Radiolabelled Emi1 (15 μl) and Plx1-translated (5 μl) interphase egg extracts were mixed and supplemented first with 4 hydroxy-5iodo-3-nitro-phenylacetyl-leucine-leucine vinylsulphone (NLVS) and subsequently with GST, GST–Pin1 or the Pin1 mutant GST–Pin1C113A in the presence of cyclin B, as described in Fig 2A. The different mixtures were immunoprecipitated with Plx1 (Anti-Plx1 IP), Emi1 (Anti-Emi1 IP) or control antibodies (CT IP) and the immunoprecipitates were analysed by autoradiography. The input and the supernatants (SN) correspond to 1 μl of mixed extracts. (D) Emi1-translated extracts were supplemented with NLVS, GST, GST–Pin1 or GST–Pin1C113A, as described above, in the presence or absence of cyclin B. Subsequently, mixes were immunoprecipitated with βtrcp antibodies and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blot with the Emi1 antibody. The input corresponds to 1 μl of non-supplemented Emi1-translated extract. Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor 1; GST, glutathione S-transferase; Pin1, protein interacting with NIMA1; Plx1, polo-like Xenopus kinase 1.

Emi1 destruction is mediated by the ubiquitin-ligase SCFβtrcp (Guardavaccaro et al, 2003). Pin1 might stabilize Emi1 proteolysis by preventing Emi1/SCFβtrcp association either by a block of Plx1–Emi1 binding and phosphorylation or by a direct inhibition of Emi1–βtrcp association. We tested both hypotheses by analysing the association of Emi1 with Plx1 and βtrcp in interphase extracts. As shown in Fig 3C, the addition of wild type or PinC113A mutant did not modify Emi1–Plx1 association; however, wild-type, but not Pin1C113A mutants, clearly prevented the association of Emi1 with βtrcp (Fig 3D). Thus, Pin1 mediates Emi1 stability by directly inhibiting Emi1–βtrcp association.

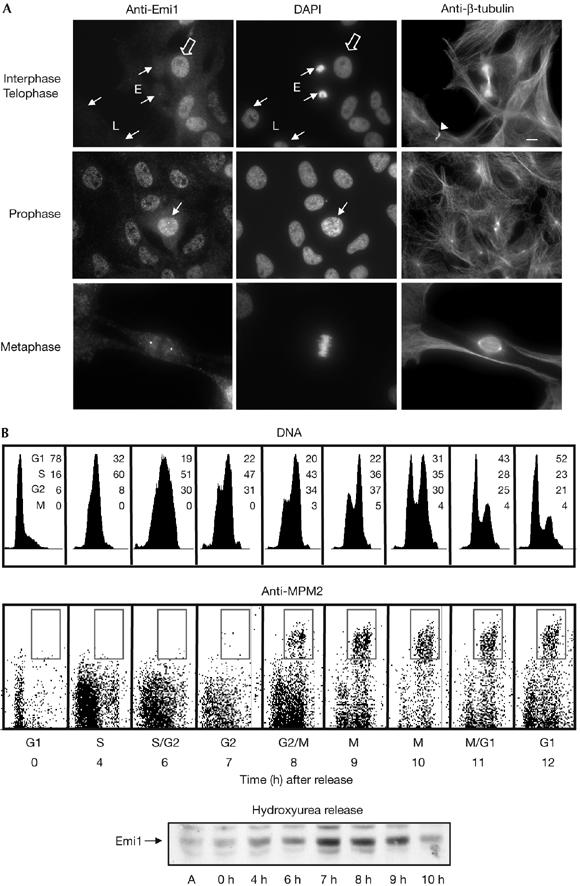

Pin1 binds and stabilizes Emi1 during G2 in XL2 cells

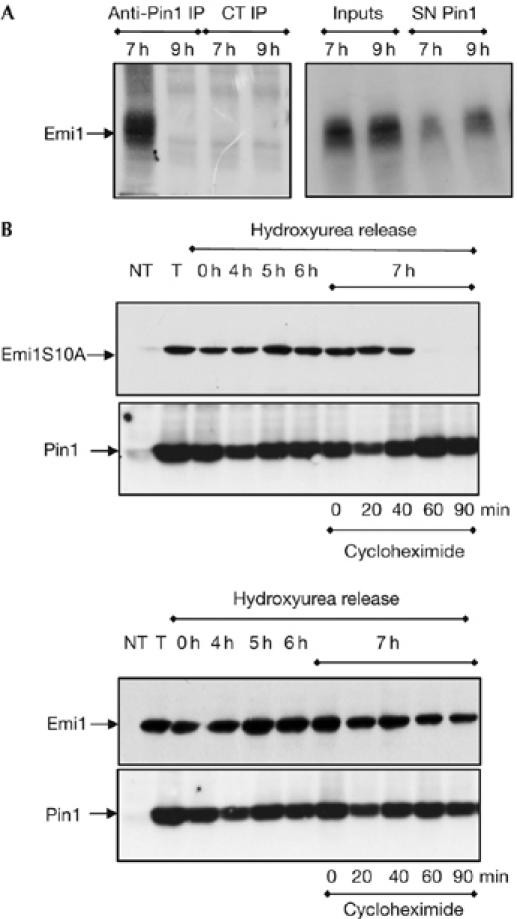

The previous results clearly indicate that, in vitro, Pin1 binds to Emi1 and prevents its SCFβtrcp-dependent degradation probably through isomerization of this protein on the Ser 10-Pro motif. To test a possible role of Pin1 in the stabilization of endogenous Emi1, we first analysed the subcellular localization of Emi1 during the cell cycle. Interphase Xenopus tadpole cells (XTC) present a punctuate staining of Emi1 preferentially in the nucleus but excluded from the nucleoli, although a residual amount is also present in the cytoplasm (Fig 4A, empty arrow). We observed a decrease in Emi1 staining at metaphase, although a considerable amount of this protein clearly stains mitotic centrosomes. Finally, we observed a gradual decrease of Emi1 from this localization as cells progressed through telophase (Fig 4A, E) and a complete disappearance of this protein as cells exited mitosis (Fig 4A, L). Next, we analysed the endogenous Emi1 levels during the cell cycle by western blot (Fig 4B). In accordance with our immunostaining results, we first observed an accumulation of the endogenous Emi1 at 4 h (S phase) reaching a peak at 7 h (G2 phase), and then a subsequent decrease of this protein from 9 to 10 h corresponding to early and late M phases, respectively. These results show that Emi1 is stable during G2 and early prophase at the time in which cyclin A/cdk (Furuno et al, 1999), Plx1, Skp1 and βtrcp (supplementary Fig S3 online) are also present and active in this compartment. To test whether Emi1 could be protected in vivo by Pin1, we first analysed, by immunoprecipitation, whether endogenous Emi1 associated with Pin1 during G2 phase. As shown in Fig 5A, the bulk of endogenous Emi1 was associated with Pin1 during G2, whereas this association completely disappeared when cells entered mitosis (Fig 5A, compare anti-Pin1 IP, 7 h versus 9 h after hydroxyurea release). These results indicate that endogenous Emi1 could be stabilized by Pin1. To characterize the physiological role of this pathway in XL2 cells further, we analysed the degradation pattern of wild-type and S10A Emi1 mutants in the presence of overexpressed Pin1 during the cell cycle. For this, asynchronous XL2 cells were transfected with either PCS2 wild-type Emi1 or S10A mutant as well as with the PCS2-Pin1 vectors. Subsequently, cells were synchronized and the levels of the two Emi1 proteins were analysed at the indicated time periods after the release of hydroxyurea. At 7 h after release, cycloheximide was added and cells were taken at different time points (0, 20, 60 and 90 min) to analyse the degradation pattern of these two proteins. As shown in Fig 5B, in the presence of ectopic Pin1, the S10A Emi1 mutant was clearly degraded at 7 h corresponding to G2, whereas the overexpression of Pin1 prevented the degradation of wild-type Emi1 protein throughout this phase of the cell cycle. From these results, we can conclude that the Emi1 degradation pathway is already active during G2 when endogenous Emi1 is stable and that overexpression of Pin1 is able to induce stabilization of Emi1 at this phase of the cell cycle. Thus, these results clearly show that the Pin1-dependent stabilization pathway of Emi1 during G2 is active in XL2 cells and that it depends on the binding of these two proteins.

Figure 4.

Emi1 localization in Xenopus tadpole cells during cell cycle. (A) XTC cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked with PBS–5% fetal bovine serum. Subsequently, coverslips were incubated with Emi1 antibody (affinity purified, 5 μg/ml) and anti-β-tubulin (mAb, 1:10). Anti-mouse Alexa 488- and anti-rabbit Alexa 555-conjugated 2° antibodies (1/600 and 1/1,000, respectively; Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (10 μg/ml) were used. Small arrows indicate cells in early (E) and late (L) telophase as well as in prophase. The arrowhead points to midbody. The empty arrow shows cells in interphase. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of synchronized XL2 cells. Cells synchronized by hydroxyurea block were collected at the indicated time points after release, labelled with MPM2 antibody and counterstained with propidium iodide. The percentage of cells in each cell cycle stage is indicated. Equal amounts of lysates from XL2 cells synchronized in (A) were taken at the indicated time points and used for immunoblotting to analyse endogenous Emi1 levels. Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor 1; XTC, Xenopus tadpole cells.

Figure 5.

Pin1 associates and stabilizes Emi1 during G2 phase in XL2 cells. (A) Equal amounts of lysates from XL2 cells synchronized in Fig 4B were taken at the indicated time points and subjected to immunoprecipitation assay by using control (CT) or Pin1 antibodies. Immunoprecipitates (IP) as well as an equal amount of inputs and supernatants (SN) were immunoblotted with Emi1 antibody and are shown. (B) XL2 asynchronous cells were either not transfected (NT) or transfected (T, 0, 4, 5 and 6 h) with PCS2 wild type or S10A Emi1 as well as with PCS2-Pin1 vectors and synchronized by hydroxyurea block. Cells were lysed at 0, 4, 5 and 6 h after hydroxyurea release and the levels of the Emi1 and Pin1 ectopic proteins were analysed by western blot. At the 7 h release time point, cells were incubated with cycloheximide and lysed at the indicated time points after protein synthesis inhibition to evaluate wild-type and S10A Emi1 degradation patterns. The low endogenous Emi1 and Pin1 levels were not visualized at the low chemiluminescence exposure time used in this experiment to show the ectopic forms. Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor 1; Pin1, protein interacting with NIMA1.

These in vivo results, together with our in vitro data, show that Pin1 binding to Emi1 is required to stabilize this protein during G2. This Pin1-dependent stabilization of Emi1 could prevent a rapid degradation of this protein just after cyclin A/cdk and Plx1 activation, ensuring the correct proteolysis of Emi1 once sufficient levels of cyclin A and B are present in the cells.

Discussion

The APC inhibitor Emi1 is required to induce S-phase and M-phase entry by driving cyclin A and cyclin B accumulation. Emi1 is first synthesized at the G1–S transition, accumulates during S and G2 phases, and is finally degraded by the SCFβtrcp pathway at prometaphase (Margottin-Goguet et al, 2003; Hansen et al, 2004). In this study, we show that cyclin A is able to induce Emi1 degradation. This suggests, that during G2 phase, in which cyclin A/cdk, Plx1 and SCFβtrcp, involved in the Emi1 degradation pathway, are active, this protein must be protected from being proteolysed. We show that, in vitro, Pin1 binds to Emi1 and stabilizes it by preventing its association with SCFβtrcp in an isomerization-dependent pathway. We also show that this association is present in XL2 cells during G2 phase and that it prevents Emi1 degradation. These results show the role of Pin1 in the stabilization of Emi1 during G2. This Pin1-dependent pathway is probably essential to allow the accumulation of sufficient cyclin A and cyclin B to drive S-phase and M-phase entry, respectively.

During the writing of this manuscript, a new study describing the role of an Emi1-associated protein—Evi5—in the stabilization of Emi1 was described (Eldridge et al, 2006). In this study, Eldridge et al have described the role of Evi5 in the stabilization of Emi1 during S/G2 phase and show that ablation of Evi5 induces precocious degradation of Emi1. However, they also show that this protein is present at low levels, clearly focused at the centrosomes. In this regard, it is difficult to explain how this small amount of centrosomal Evi5 could stabilize the bulk of Emi1, which represents an important amount of protein localized throughout the nucleus. In contrast to Evi5, Pin1 is present at much higher levels and is localized in the same nuclear compartment as Emi1 during G2 (data not shown). Therefore, it is likely that two different mechanisms are involved in the stabilization of Emi1. Pin1-dependent protection could prevent the degradation of the bulk of nuclear Emi1 during G2, whereas Evi5 could protect the centrosomal subpopulation of Emi1, which would be degraded later during mitosis. Both pathways would be required to ensure a correct time-course degradation of Emi1.

Methods

Degradation assays. Xenopus egg extracts and protein translation were carried out as described in the supplementary information online. For Emi1 degradation assays, 2.8 μl of 35S-labelled protein was incubated at 21°C with 20 μl of interphase extract supplemented, or not, with 50 ng of recombinant GST–cyclin B. At the indicated time points, 2.8 μl of the mixture was recovered and analysed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

Site-directed mutagenesis. Protein sequence point mutations and deletions were obtained by using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The mutation of Cys 113 to Ala in human Pin1 corresponds to the previously described mutation of Cys 109 to Ala in the Xenopus Pin1 (Winkler et al, 2000).

GST pulldown and immunoprecipitation. Thirty microlitres of Emi1 wild type or mutated form translated in Xenopus interphase egg extract, supplemented with 2 mM of proteasome inhibitor 4 hydroxy-3-iodo-2-nitrophenyl-leucinyl-leucinyl-leucine vinyl sulphone, was incubated with 20 μl of glutathione–sepharose beads containing GST–Pin1 or control GST proteins for 30 min at 21°C. Thereafter, 75 ng of GST–cycB was added, or not, to the mix and incubated for 30 min at 21°C. The supernatants were removed, washed and used for western blot analysis. Immunoprecipitations were carried out by using 20 μl of magnetic Protein A-Dynabeads (Dynal®, Compiègne, France) and 3 μg of each antibody. Beads were washed and incubated for 45 min at room temperature with 20 μl of Xenopus egg extracts. cDNA cloning and immunization procedures were carried out as described in the supplementary information online.

Cell transfection. XL2 cells were synchronized and analysed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, as described in the supplementary information online. Plasmid transfections used Fugene 6 (Roche, Meylan, France) according to the manufacturer's protocols. To analyse the degradation pattern of Emi1, asynchronous XL2 cells were transfected with PCS2-Emi1 or PCS2-S10A mutant as well as PCS2-Pin1 and synchronized by hydroxyurea block. At 7 h after release, the cells were incubated with 20 μg/ml of cycloheximide, collected at 0, 20, 40, 60 and 90 min after protein synthesis inhibition and analysed by western blot.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

supplementary Fig S1

supplementary Fig S2

supplementary Fig S3

supplementary information

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr G. Lippens for the generous gift of pGEX-Pin1 plasmid. We are also indebted to Dr A. Devault for a critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (Equipe Labellisée). A.B. is a CJ Martin fellowship.

References

- Castro A, Bernis C, Vigneron S, Labbe JC, Lorca T (2005) The anaphase-promoting complex: a key factor in the regulation of cell cycle. Oncogene 24: 314–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge AG, Loktev AV, Hansen DV, Verschuren EW, Reimann JD, Jackson PK (2006) The Evi5 oncogene regulates cyclin accumulation by stabilizing the anaphase-promoting complex inhibitor Emi1. Cell 27: 367–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuno N, den Elzen N, Pines J (1999) Human cyclin A is required for mitosis until mid prophase. J Cell Biol 147: 295–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardavaccaro D, Kudo Y, Boulaire J, Barchi M, Busino L, Donzelli M, Margottin-Goguet F, Jackson PK, Yamasaki L, Pagano M (2003) Control of meiotic and mitotic progression by the F box protein β-Trcp1 in vivo. Dev Cell 4: 799–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DV, Loktev AV, Ban KH, Jackson PK (2004) Plk1 regulates activation of the anaphase promoting complex by phosphorylating and triggering SCFβTrCP-dependent destruction of the APC inhibitor Emi1. Mol Biol Cell 15: 5623–5634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JY, Reimann JD, Sorensen CS, Lukas J, Jackson PK (2002) E2F-dependent accumulation of hEmi1 regulates S phase entry by inhibiting APC(Cdh1). Nat Cell Biol 4: 358–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JD, Yeh ES, Swenson KI, Means AR, Winkler KE (2003) The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1. Prog Cell Cycle Res 5: 477–487 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu KP, Hanes SD, Hunter T (1996) A human peptidyl-prolyl isomerase essential for regulation of mitosis. Nature 380: 544–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu KP, Liou YC, Zhou XZ (2002) Pinning down proline-directed phosphorylation signaling. Trends Cell Biol 12: 164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margottin-Goguet F, Hsu JY, Loktev A, Hsieh HM, Reimann JD, Jackson PK (2003) Prophase destruction of Emi1 by the SCF(βTrCP/Slimb) ubiquitin ligase activates the anaphase promoting complex to allow progression beyond prometaphase. Dev Cell 4: 813–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann JD, Freed E, Hsu JY, Kramer ER, Peters JM, Jackson PK (2001) Emi1 is a mitotic regulator that interacts with Cdc20 and inhibits the anaphase promoting complex. Cell 105: 645–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Drogen F, Sangfelt O, Malyukova A, Matskova L, Yeh E, Means AR, Reed SI (2006) Ubiquitylation of cyclin E requires the sequential function of SCF complexes containing distinct hCdc4 isoforms. Mol Cell 23: 37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler KE, Swenson KI, Kornbluth S, Means AR (2000) Requirement of the prolyl isomerase Pin1 for the replication checkpoint. Science 287: 1644–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulf G, Finn G, Suizu F, Lu KP (2005) Phosphorylation-specific prolyl isomerization: is there an underlying theme? Nat Cell Biol 7: 435–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MB et al. (1997) Sequence-specific and phosphorylation-dependent proline isomerization: a potential mitotic regulatory mechanism. Science 278: 1957–1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supplementary Fig S1

supplementary Fig S2

supplementary Fig S3

supplementary information