Abstract

Presenilin mutations are the main cause of familial Alzheimer disease. From a genetic point of view, these mutations seem to result in a gain of toxic function; however, biochemically, they result in a partial loss of function in the γ-secretase complex, which affects several downstream signalling pathways. Consequently, the current genetic terminology is misleading. In fact, the available data indicate that several clinical presenilin mutations also lead to a decrease in amyloid precursor protein-derived amyloid β-peptide generation, further implying that presenilin mutations are indeed loss-of-function mutations. The loss of function of presenilin causes incomplete digestion of the amyloid β-peptide and might contribute to an increased vulnerability of the brain, thereby explaining the early onset of the inherited form of Alzheimer disease. In this review, I evaluate the implications of this model for the amyloid-cascade hypothesis and for the efficacy of presenilin/γ-secretase as a drug target.

Keywords: Alzheimer, gain or loss of function, presenilin

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a common and disabling disorder. Its incidence increases exponentially with age and therefore it is a significant public-health concern. Only symptomatic treatment is currently available; however, there is a legitimate hope for a cure thanks to the tremendous progress that is being made in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of the disease. The dominant theory in the field is the ‘amyloid-cascade hypothesis', which links abnormal amyloid precipitates in the brain with neuronal dysfunction, the induction of tangles and dementia (Hardy & Higgins, 1992). The logical correlate is that drugs that either block amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) generation or increase its clearance, for example by vaccination, will cure or halt the progression of AD. Although a great deal of evidence supports this relatively simple and straightforward concept (Annaert & De Strooper, 2002; Hardy & Selkoe, 2002), there is no proof that this theory has clinical relevance. As a result, the amyloid-cascade hypothesis has received some criticism in recent years. The current discussion revolves around presenilin 1 (encoded by PSEN1), and the extent to which gain or loss of function of this gene (Fig 1) contributes to the pathological spectrum of early-onset familial AD. Presenilin 1—along with the closely related presenilin 2—is the catalytic component of the γ-secretase enzyme, which cleaves the amyloid precursor protein (APP) into Aβs of varying lengths (De Strooper et al, 1998). The discussion is complicated by the fact that researchers use different strategies to evaluate PSEN function and, although evidence indicates that PSEN mutations result in changes in Aβ generation in accordance with the amyloid-cascade hypothesis (Scheuner et al, 1996), the complete loss of Psen function in the brains of mice results in neurodegeneration in the total absence of Aβ generation (Saura et al, 2004). This latter research has led to the theory that Aβ generation is not necessary for the development of AD.

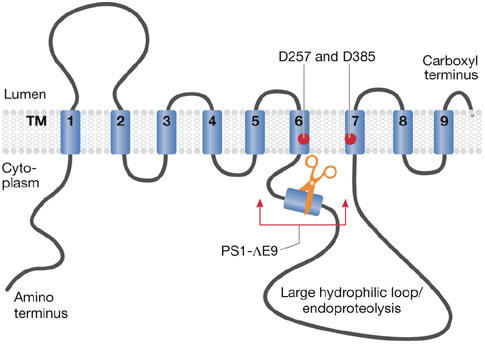

Figure 1.

Nine-transmembrane topology for presenilin. Presenilin is schematically represented. Two aspartate residues in transmembrane domains (TMs) 6 and 7 constituting the catalytic site are indicated. The Δexon9 mutation (PS1–DE9) deletes the indicated region of the protein.

Clinical mutations in PSEN1 cause AD

So far, more than 150 familial AD-causing mutations in PSEN1 have been identified, approximately 10 additional mutations have been found in the homologous gene PSEN2 and 25 mutations have been identified in the APP gene (http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/ADMutations). The study of PSEN1 is therefore crucial for understanding the pathogenesis of familial AD.

Most mutations in PSEN1 are simple missense mutations that result in single amino-acid substitutions in presenilin 1. Some are more complex, for example, small deletions, insertions or splice mutations. The most severe mutation in PSEN1 is a donor–acceptor splice mutation that causes two amino-acid substitutions and an in-frame deletion of exon 9 (Fig 1). Significantly, however, the biochemical consequences of these mutations for γ-secretase assembly are limited (Bentahir et al, 2006; Steiner et al, 1999). Although as many as one-third of the 467 amino acids in the open-reading frame of presenilin 1 are affected by disease-causing mutations, a truncation or absence of the protein has never been observed, indicating that haploinsufficiency does not cause AD. Rather, at first glance and from a strictly genetic perspective, these different clinical mutations all seem to lead to a specific gain of toxic function for PSEN1. Investigations over several years, however, have not succeeded in translating this genetic concept into molecular terms—that is, explaining how the mutations scattered over presenilin 1 all cause a similar gain of toxic function in the protein.

Mutations in either presenilin or APP consistently increase the relative ratio between the long (Aβ42) and short (Aβ40) amyloid peptides (Aβ42/Aβ40; Borchelt et al, 1996; Scheuner et al, 1996). Given that inactivation of Psen1 and Psen2 completely prevents Aβ generation (Herreman et al, 2000; Zhang et al, 2000), this increase can indeed be explained as a gain of toxic function. However, the change in ratio can also be the consequence of a partial loss of Aβ40 generation, as is the case with several PSEN mutations discussed in detail below. Indeed, several authors have challenged the dominant gain-of-toxic-function hypothesis over the years. First, wild-type human PSEN1 can effectively rescue the loss of its suppressor of Notch-family member lin-12 (sel-12) homologue in Caenorhabditis elegans, whereas a mutated PSEN1 is less effective or not effective at all (Baumeister et al, 1997; Levitan et al, 1996). Second, Shen and co-workers have shown that a total loss of Psen function in the forebrain of mice causes neurodegenerative disease in the absence of Aβ (Saura et al, 2004). Third, several groups have reported that specific loss of Psen1 in the mouse forebrain affects particular aspects of memory (Feng et al, 2001; Yu et al, 2001). Both neurodegeneration and memory deficits are important features of AD; however, it might be dangerous to extrapolate these observations to human pathology. Accordingly, it is difficult to correlate the total loss of four Psen alleles in a mouse model (Saura et al, 2004) with the relatively mild single mutation of one PSEN allele in familial AD patients. Indeed, neurodegenerative phenotypes have not been observed in animal models with only one allele inactivated (Psen1+/− or Psen2+/−; for a more detailed overview of the different Psen-knockout mouse models, see Marjaux et al, 2004). Furthermore, it is unclear whether the memory deficits in mice with a forebrain-specific Psen1-knockout can really be compared with the memory deficits in patients with AD. In this regard, some of the memory deficits that result from APP overexpression in AD mouse models can be alleviated by Psen1 inactivation (Dewachter et al, 2002; Saura et al, 2005). Fourth, in the past few years, some studies have indicated that genuine loss-of-function PSEN1 mutations could be involved in forms of frontotemporal dementia without the involvement of Aβ (Amtul et al, 2002; Dermaut et al, 2004; Raux et al, 2000). However, formal genetic or molecular proof that these mutations are responsible for the neurodegenerative process in these patients has not been provided. In fact, an additional mutation in the progranulin gene (Baker et al, 2006; Cruts et al, 2006) in a patient with the presenilin 1 Arg352 insertion (Boeve et al, 2006) is probably the cause of the dementia, which implies that, at least in this case, the mutation in presenilin 1 is a polymorphism. Finally, promotor polymorphisms in the PSEN1 gene that decrease its expression contribute to the risk of early-onset AD (Theuns et al, 2000); however, whether these affect amyloid generation is not yet known.

In conclusion, although the current research clearly indicates that presenilin 1 is important for maintaining the integrity of the brain, it is less clear whether the severe deficits in homozygous loss-of-function mouse models are relevant to the pathology in human patients. Furthermore, PSEN1 deficiency is unlikely to contribute to the disease process in patients with APP mutations, which implies that the effects of loss of PSEN1 function on APP processing are crucial for our understanding of the pathogenesis of AD. I do not, however, exclude the possibility that partial dysfunction of PSEN1—for example, in the Notch signalling pathway that modulates neurite outgrowth and brain repair—makes the brain more prone to Aβ toxicity. This would fit with the previously proposed ‘two-hit' model for AD (Marjaux et al, 2004), and would also explain why familial AD generally strikes earlier and is more aggressive than sporadic AD.

Presenilin as part of the γ-secretase complex

Presenilin provides the catalytic core of γ-secretase, which removes short transmembrane protein fragments from the cell membrane (De Strooper, 2003). γ-secretase is a highly hydrophobic complex (Fig 2) consisting of at least three additional subunits—nicastrin, Aph1 and Pen2—which, together with presenilin, form a barrel-like structure in the membrane (Lazarov et al, 2006). Water, which is necessary for the catalytic activity of the complex, is present in this structure (Tolia et al, 2006). Considering the fact that there are two PSEN genes and two APH genes, at least four different complexes with potentially different biological functions (Serneels et al, 2005) could co-exist in cells and tissues (Hébert et al, 2004; Shirotani et al, 2004). The current models indicate that the aminopeptidase-like domain of nicastrin, which functions as an exosite on the protease, provides a docking site for γ-secretase substrates (Shah et al, 2005). Significantly, more than 30 different substrates have been identified, including APP. Following sequential cleavage of APP by the β-secretases and γ-secretases, the major proteolytic products—Aβ and the APP intracellular domain (AICD)—are released extracellularly and intracellularly, respectively. Although it has been frequently proposed that AICD is a signalling molecule similar to the Notch intracellular domain (NICD; Hébert et al, 2006; Kopan & Ilagan, 2004; Marambaud et al, 2003), this has not been rigorously proven.

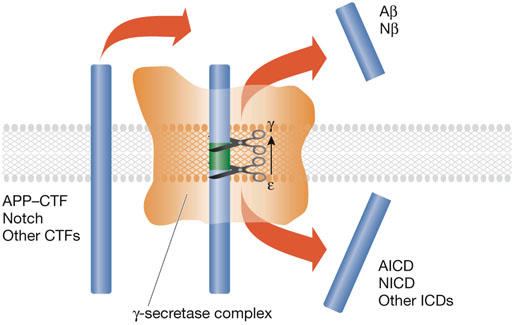

Figure 2.

The γ-secretase. Schematic drawing of the ‘barrel' structure of the γ-secretase (orange). The arrow indicates progressive ε-to-γ cleavage of the substrate (blue bars). The possibility of unfolding of the substrate is discussed in the main text. Aβ, amyloid β-peptide; AICD, APP intracellular domain; APP, amyloid precursor protein; CTF, carboxy-terminal fragment; ICD, intracellular domain; Nβ, Notch β-like fragment; NICD, Notch intracellular domain.

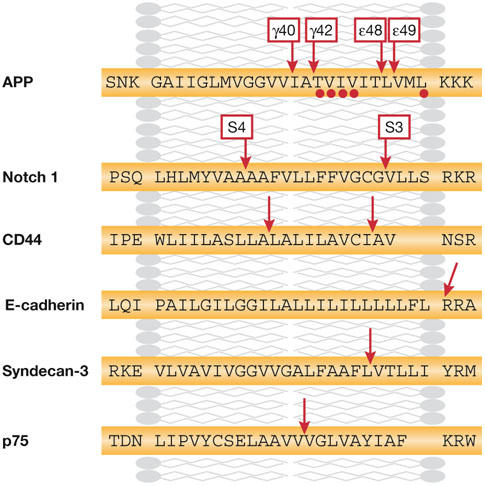

Sequence determination of the carboxyl terminus of Aβ and the amino terminus of AICD has revealed heterogeneity (Fig 3). There are two γ-cleavage products, which end at either residue Val40 (Aβ40) or residue Ala42 (Aβ42). The AICD peptide starts at Val51 or Met52 and these cleavages are recognized as the ε-site cleavage products (Fig 3). Similar dual cleavages have been identified for Notch (Okochi et al, 2002) and CD44 (Lammich et al, 2002). Evidence indicates that γ-secretase cuts APP initially at the ε-site and then progressively removes C-terminal residues until the γ-cleavage site has been reached (Fig 2; Kakuda et al, 2006). It is likely that the hydrophobicity of the remaining peptide is then sufficiently reduced to facilitate its release into the extracellular medium. This model would explain the following observations: neither AICD nor NICD peptide fragments that extend N-terminally beyond the ε-site have been detected (Chandu et al, 2006; Kakuda et al, 2006); longer Aβs—Aβ43 up to Aβ49—can be detected in cell extracts (Qi-Takahara et al, 2005; Yagishita et al, 2006; Zhao et al, 2005); tryptophan mutations introduced between the ε- and γ-cleavage sites in APP block cleavage at the γ-site (Sato et al, 2005); and a product–precursor relationship has been detected between long and short forms of Aβ (Qi-Takahara et al, 2005; Yagishita et al, 2006).

Figure 3.

Cleavage sites of selected γ-secretase substrates. The transmembrane sequences of several substrates of the γ-secretase are indicated. Red arrows indicate cleavage sites deduced from amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal sequencing. APP, amyloid precursor protein.

Alternative models are more complicated, invoking, for example, additional catalytic sites in γ-secretase or carboxypeptidases that act after the initial ε-site cleavage. It remains unclear how substrates are progressively cleaved in the same catalytic site. It is possible that the α-helix of putative substrates unfolds after ε-site cleavage, which, in turn, advances the next bound peptide towards the catalytic site for further cleavage. The consecutive cleavage of APP could provide an explanation for how loss-of-function mutations in PSEN1 might result in decreased Aβ generation and simultaneous increased production of long Aβ (Bentahir et al, 2006; Kumar-Singh et al, 2006; Qi et al, 2003).

PSEN mutations are loss-of-function mutations

The first in vivo evidence that PSEN mutations cause a loss of Notch signalling was provided in C. elegans (Baumeister et al, 1997; Levitan et al, 1996). However, two follow-up reports in mice did not correlate with these observations (Davis et al, 1998; Qian et al, 1998). The discrepancy in these studies might be explained by the fact that in the mouse studies, the authors used a Psen1 Ala246Glu mutation under a heterologous promotor in their rescue experiments and observed only a partial rescue of the phenotype. Furthermore, in cell-based assays, this mutation resulted in only a 20% reduction in the cleavage of Notch (Bentahir et al, 2006). These rescue experiments have not shed light on PSEN loss-of-function mutations. Knock-in mutations provide a better way to address this question. Several mutant mice have been described with relatively mild phenotypes (Guo et al, 1999; Nakano et al, 1999; Siman et al, 2000). Memory deficits were observed in one mouse model containing two diseased alleles, which were rescued in heterozygous mice indicating a loss-of-function phenotype (Wang et al, 2004). Experiments in cell lines unequivocally confirm that PSEN mutants decrease the cleavage of Notch, syndecan and N-cadherin, and this can probably be extended to other substrates (Baki et al, 2001; Bentahir et al, 2006; Schroeter et al, 2003; Song et al, 1999). Therefore, PSEN mutations result in a loss of function of the γ-secretase. In fact, a wealth of additional experiments examining PSEN function in protein trafficking, apoptosis, autophagy, calcium homeostasis, β-catenin turnover, regulation of kinase pathways and tau phosphorylation all support the loss-of-function interpretation. These topics are not discussed further within the scope of this review.

Loss of γ-secretase changes the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio

The effects of PSEN clinical mutations on APP processing have mostly been investigated by analysing the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio; this permits the normalization of differences in APP or presenilin expression in different cell lines and is considered to be a prominent factor for disease progression in familial AD patients (Borchelt et al, 1996; Duff et al, 1996; Scheuner et al, 1996). More than 10 years ago, Jarrett and Lansbury described Aβ42 as a ‘nucleation' factor, which notably accelerates the aggregation of Aβ into amyloid in vitro (Jarrett & Lansbury, 1993). Direct evidence for the importance of Aβ42 in AD came from a biochemical analysis of the APP Val717Ile clinical mutation (Goate et al, 1991). This mutation and several others all cause an increase in the generation of Aβ42 relative to Aβ40 (Suzuki et al, 1994). Finally, Aβ42, although generated by neurons at a tenfold lower rate than Aβ40, is the main component of amyloid plaques in the brains of AD patients (Iwatsubo et al, 1994).

Given the enormous differences in the biophysical properties of the Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides, it is surprising that the AD field has spent so much time focusing on the quantitative rather than the qualitative aspects of this increased ratio. For instance, the combination of a mutant Psen1 allele with a Psen1-null allele causes accelerated amyloidosis, whereas the combination of the same mutant with a wild-type Psen1 allele is protective, even with an absolute increase in γ-secretase activity (Wang et al, 2006). Furthermore, expression of Aβ42—but not Aβ40—alone is sufficient to cause amyloidosis in transgenic mice (McGowan et al, 2005).

The effects of PSEN clinical mutations on APP processing were recently re-evaluated in cell-culture systems. Mutants were either expressed in a Psen-negative background (Bentahir et al, 2006; Walker et al, 2005) or stably transfected (Kumar-Singh et al, 2006) and the levels of expression were carefully monitored. These studies analysed the absolute levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42, and, importantly, the accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments, which are direct substrates for γ-secretase. An increase in Aβ42/Aβ40 was confirmed; however, this was due to a decrease in Aβ40 peptide levels in several mutants. Importantly, all cell lines accumulated APP C-terminal fragments and showed decreased generation of the cytoplasmic AICD (Bentahir et al, 2006; Kumar-Singh et al, 2006; Walker et al, 2005; Wiley et al, 2005), thereby establishing that PSEN mutations result in a loss of γ-secretase cleavage of APP. This apparently translates into an ‘incomplete digestion' of the APP substrate, generating fewer but longer Aβs (Qi et al, 2003; Yagishita et al, 2006). It is therefore clear that biochemical loss of function of presenilin can cause AD. The confusion with the genetic gain-of-toxic-function view can, however, be resolved because the loss-of-Psen mutations act indirectly in the disease process, causing a gain of toxic function of the APP gene by the incomplete digestion of Aβ.

Implications for the amyloid-cascade hypothesis

Since the original amyloid-cascade hypothesis for AD was put forward (Hardy & Higgins, 1992), many modifications and refinements have been proposed to incorporate new observations and to resolve apparent conflicts. For example, no absolute relationship exists between amyloid load in the brain and the clinical manifestation of AD symptoms in humans (Price & Morris, 1999) or mice (Games et al, 1995). This has led to the concept of Aβ-derived diffusible ligands (Lambert et al, 1998) or ‘soluble toxic oligomers' (Glabe, 2006; Lambert et al, 1998; Walsh et al, 2002). These Aβ oligomers are intermediary forms between free soluble Aβs and insoluble amyloid fibres, and seem to be toxic both in vitro and in vivo. Although the molecular nature of these oligomers remains elusive, they have been isolated from transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells (Walsh et al, 2002) and as a 56-kDa oligomer from transgenic mouse brains (Lesne et al, 2006). The extent to which PSEN1 mutations generate mixtures of Aβs that are more prone to form toxic oligomers remains to be investigated; however, this concept could explain cases of AD in which smaller amounts of Aβ are generated. More research is needed to determine the biophysical and biochemical properties of this species. However, we are clearly moving away from amyloid plaques and fibrils towards a more functional definition of Aβ toxicity, and it might be appropriate to indicate this paradigm shift by addressing the ‘Aβ-tangle cascade' hypothesis in the future.

There are important implications for therapeutic approaches to AD. It is now essential to investigate how different Aβ-peptide species contribute to the generation, stability and toxic properties of the oligomers. The relative combination of these peptides could be much more important than the total load of Aβ in the brain. Inhibiting Aβ generation by β- or γ-secretase inhibitors might still be a good idea, considering the fact that a reduction of the overall load of free peptide will probably influence the balance between Aβ in free, oligomeric and amyloid fibril conformations; however, it is becoming increasingly crucial to elucidate the extent to which the last of these is in equilibrium with the toxic oligomer conformation. γ-secretase inhibitors might provide additional possibilities because some have been shown to modulate the activity of the enzyme by shifting the spectrum of Aβs to shorter, probably more soluble forms, like the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Weggen et al, 2003), or to longer membrane-bound peptides, such as the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT (Qi-Takahara et al, 2005; Yagishita et al, 2006). For non-catalytic site-directed inhibitors of γ-secretase, the observed paradoxical increases in Aβ42 might be explained by this vision. However, before testing these drugs in the clinic, it will be important to investigate the fate of the peptides in biological systems, and to determine how the other forms of Aβ contribute to the generation and stabilization of Aβ oligomers.

Bart De Strooper

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks A. Thathiah, K. Devriendt, E. Legius, T. Golde, M. Hutton and B. Boeve for interesting discussions. The author is supported by a Freedom to Discover grant (Bristol Myers Squib), a Pioneer award (Alzheimer's Association), the Fund for Scientific Research (Flanders), K.U.Leuven (GOA), the European Union (APOPIS: LSHM-CT-2003-503330) and the Federal Office for Scientific Affairs (Belgium).

References

- Amtul Z et al. (2002) A presenilin 1 mutation associated with familial frontotemporal dementia inhibits γ-secretase cleavage of APP and notch. Neurobiol Dis 9: 269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annaert W, De Strooper B (2002) A cell biological perspective on Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 18: 25–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M et al. (2006) Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature 442: 916–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baki L et al. (2001) Presenilin-1 binds cytoplasmic epithelial cadherin, inhibits cadherin/p120 association, and regulates stability and function of the cadherin/catenin adhesion complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 2381–2386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R, Leimer U, Zweckbronner I, Jakubek C, Grunberg J, Haass C (1997) Human presenilin-1, but not familial Alzheimer's disease (FAD) mutants, facilitate Caenorhabditis elegans Notch signalling independently of proteolytic processing. Genes Funct 1: 149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentahir M, Nyabi O, Verhamme J, Tolia A, Horre K, Wiltfang J, Esselmann H, De Strooper B (2006) Presenilin clinical mutations can affect γ-secretase activity by different mechanisms. J Neurochem 96: 732–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeve BF et al. (2006) Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism associated with the IVS1+1G->A mutation in progranulin: a clinicopathologic study. Brain 129: 3103–3114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt DR et al. (1996) Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 17: 1005–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandu D, Huppert SS, Kopan R (2006) Analysis of transmembrane domain mutants is consistent with sequential cleavage of Notch by γ-secretase. J Neurochem 98: 2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruts M et al. (2006) Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature 422: 920–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JA, Naruse S, Chen H, Eckman C, Younkin S, Price DL, Borchelt DR, Sisodia SS, Wong PC (1998) An Alzheimer's disease-linked PS1 variant rescues the developmental abnormalities of PS1-deficient embryos. Neuron 20: 603–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B (2003) Aph-1, Pen-2, and nicastrin with presenilin generate an active γ-secretase complex. Neuron 38: 9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Vanderstichele H, Guhde G, Annaert W, Von Figura K, Van Leuven F (1998) Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature 391: 387–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermaut B et al. (2004) A novel presenilin 1 mutation associated with Pick's disease but not β-amyloid plaques. Ann Neurol 55: 617–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewachter I et al. (2002) Neuronal deficiency of presenilin 1 inhibits amyloid plaque formation and corrects hippocampal long-term potentiation but not a cognitive defect of amyloid precursor protein [V717I] transgenic mice. J Neurosci 22: 3445–3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff K et al. (1996) Increased amyloid-β42(43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1. Nature 383: 710–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R et al. (2001) Deficient neurogenesis in forebrain-specific presenilin-1 knockout mice is associated with reduced clearance of hippocampal memory traces. Neuron 32: 911–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Games D et al. (1995) Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. Nature 373: 523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe CG (2006) Common mechanisms of amyloid oligomer pathogenesis in degenerative disease. Neurobiol Aging 27: 570–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goate A et al. (1991) Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature 349: 704–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Fu W, Sopher BL, Miller MW, Ware CB, Martin GM, Mattson MP (1999) Increased vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to excitotoxic necrosis in presenilin-1 mutant knock-in mice. Nat Med 5: 101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297: 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA (1992) Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256: 184–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert SS, Serneels L, Dejaegere T, Horré K, Dabrowski M, Baert V, Annaert W, Hartmann D, De Strooper B (2004) Coordinated and widespread expression of γ-secretase in vivo: evidence for size and molecular heterogeneity. Neurobiol Dis 17: 260–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert SS, Serneels L, Tolia A, Craessaerts K, Derks C, Filippov MA, Muller U, De Strooper B (2006) Regulated intramembrane proteolysis of amyloid precursor protein and regulation of expression of putative target genes. EMBO Rep 7: 739–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herreman A, Serneels L, Annaert W, Collen D, Schoonjans L, De Strooper B (2000) Total inactivation of γ-secretase activity in presenilin-deficient embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 2: 461–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y (1994) Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43). Neuron 13: 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett JT, Lansbury PT Jr (1993) Seeding “one-dimensional crystallization” of amyloid: a pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie? Cell 73: 1055–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuda N, Funamoto S, Yagishita S, Takami M, Osawa S, Dohmae N, Ihara Y (2006) Equimolar production of amyloid β-protein and amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain from β-carboxyl-terminal fragment by γ-secretase. J Biol Chem 281: 14776–14786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R, Ilagan MX (2004) γ-secretase: proteasome of the membrane? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar-Singh S, Theuns J, Van Broeck B, Pirici D, Vennekens K, Corsmit E, Cruts M, Dermaut B, Wang R, Van Broeckhoven C (2006) Mean age-of-onset of familial Alzheimer disease caused by presenilin mutations correlates with both increased Aβ42 and decreased Aβ40. Hum Mutat 27: 686–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP et al. (1998) Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 6448–6453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammich S, Okochi M, Takeda M, Kaether C, Capell A, Zimmer AK, Edbauer D, Walter J, Steiner H, Haass C (2002) Presenilin-dependent intramembrane proteolysis of CD44 leads to the liberation of its intracellular domain and the secretion of an Aβ-like peptide. J Biol Chem 277: 44754–44759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov VK, Fraering PC, Ye W, Wolfe MS, Selkoe DJ, Li H (2006) Electron microscopic structure of purified, active γ-secretase reveals an aqueous intramembrane chamber and two pores. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 6889–6894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH (2006) A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature 440: 352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan D, Doyle TG, Brousseau D, Lee MK, Thinakaran G, Slunt HH, Sisodia SS, Greenwald I (1996) Assessment of normal and mutant human presenilin function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 14940–14944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marambaud P, Wen PH, Dutt A, Shioi J, Takashima A, Siman R, Robakis NK (2003) A CBP binding transcriptional repressor produced by the PS1/ε-cleavage of N-cadherin is inhibited by PS1 FAD mutations. Cell 114: 635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjaux E, Hartmann D, De Strooper B (2004) Presenilins in memory, Alzheimer's disease, and therapy. Neuron 42: 189–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan E et al. (2005) Aβ42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron 47: 191–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Kondoh G, Kudo T, Imaizumi K, Kato M, Miyazaki JI, Tohyama M, Takeda J, Takeda M (1999) Accumulation of murine amyloid β42 in a gene-dosage-dependent manner in PS1 ‘knock-in' mice. Eur J Neurosci 11: 2577–2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okochi M, Steiner H, Fukumori A, Tanii H, Tomita T, Tanaka T, Iwatsubo T, Kudo T, Takeda M, Haass C (2002) Presenilins mediate a dual intramembranous γ-secretase cleavage of Notch-1. EMBO J 21: 5408–5416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL, Morris JC (1999) Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 45: 358–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Morishima-Kawashima M, Sato T, Mitsumori R, Ihara Y (2003) Distinct mechanisms by mutant presenilin 1 and 2 leading to increased intracellular levels of amyloid β-protein 42 in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochemistry 42: 1042–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian S, Jiang P, Guan XM, Singh G, Trumbauer ME, Yu H, Chen HY, Van de Ploeg LH, Zheng H (1998) Mutant human presenilin 1 protects presenilin 1 null mouse against embryonic lethality and elevates Aβ1-42/43 expression. Neuron 20: 611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi-Takahara Y et al. (2005) Longer forms of amyloid β protein: implications for the mechanism of intramembrane cleavage by γ-secretase. J Neurosci 25: 436–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raux G, Gantier R, Thomas-Anterion C, Boulliat J, Verpillat P, Hannequin D, Brice A, Frebourg T, Campion D (2000) Dementia with prominent frontotemporal features associated with L113P presenilin 1 mutation. Neurology 55: 1577–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Tanimura Y, Hirotani N, Saido TC, Morishima-Kawashima M, Ihara Y (2005) Blocking the cleavage at midportion between γ- and ε-sites remarkably suppresses the generation of amyloid β-protein. FEBS Lett 579: 2907–2912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura CA, Chen G, Malkani S, Choi SY, Takahashi RH, Zhang D, Gouras GK, Kirkwood A, Morris RG, Shen J (2005) Conditional inactivation of presenilin 1 prevents amyloid accumulation and temporarily rescues contextual and spatial working memory impairments in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci 25: 6755–6764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura CA et al. (2004) Loss of presenilin function causes impairments of memory and synaptic plasticity followed by age-dependent neurodegeneration. Neuron 42: 23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D et al. (1996) Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med 2: 864–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter EH et al. (2003) A presenilin dimer at the core of the γ-secretase enzyme: insights from parallel analysis of Notch 1 and APP proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 13075–13080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serneels L et al. (2005) Differential contribution of the three Aph1 genes to γ-secretase activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 1719–1724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Lee SF, Tabuchi K, Hao YH, Yu C, LaPlant Q, Ball H, Dann CE III, Sudhof T, Yu G (2005) Nicastrin functions as a γ-secretase-substrate receptor. Cell 122: 435–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirotani K, Edbauer D, Prokop S, Haass C, Steiner H (2004) Identification of distinct γ-secretase complexes with different APH-1 variants. J Biol Chem 279: 41340–41345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siman R, Reaume AG, Savage MJ, Trusko S, Lin YG, Scott RW, Flood DG (2000) Presenilin-1 P264L knock-in mutation: differential effects on aβ production, amyloid deposition, and neuronal vulnerability. J Neurosci 20: 8717–8726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Nadeau P, Yuan M, Yang X, Shen J, Yankner BA (1999) Proteolytic release and nuclear translocation of Notch-1 are induced by presenilin-1 and impaired by pathogenic presenilin-1 mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6959–6963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Romig H, Grim MG, Philipp U, Pesold B, Citron M, Baumeister R, Haass C (1999) The biological and pathological function of the presenilin-1 dExon 9 mutation is independent of its defect to undergo proteolytic processing [In Process Citation]. J Biol Chem 274: 7615–7618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Cheung TT, Cai XD, Odaka A, Otvos L Jr, Eckman C, Golde TE, Younkin SG (1994) An increased percentage of long amyloid β protein secreted by familial amyloid β protein precursor (βAPP717) mutants. Science 264: 1336–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theuns J, Del-Favero J, Dermaut B, van Duijn CM, Backhovens H, Van den Broeck MV, Serneels S, Corsmit E, Van Broeckhoven CV, Cruts M (2000) Genetic variability in the regulatory region of presenilin 1 associated with risk for Alzheimer's disease and variable expression. Hum Mol Genet 9: 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolia A, Chavez-Gutierrez L, De Strooper B (2006) Contribution of presenilin transmembrane domains 6 and 7 to a water-containing cavity in the γ-secretase complex. J Biol Chem 281: 27633–27642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker ES, Martinez M, Brunkan AL, Goate A (2005) Presenilin 2 familial Alzheimer's disease mutations result in partial loss of function and dramatic changes in Aβ 42/40 ratios. J Neurochem 92: 294–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ (2002) Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416: 535–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Dineley KT, Sweatt JD, Zheng H (2004) Presenilin 1 familial Alzheimer's disease mutation leads to defective associative learning and impaired adult neurogenesis. Neuroscience 126: 305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Wang B, He W, Zheng H (2006) Wild-type presenilin 1 protects against Alzheimer's disease mutation-induced amyloid pathology. J Biol Chem 281: 15330–15336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weggen S, Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Pietrzik CU, Ozols V, Fauq A, Golde TE, Koo EH (2003) Evidence that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs decrease amyloid β 42 production by direct modulation of γ-secretase activity. J Biol Chem 278: 31831–31837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JC, Hudson M, Kanning KC, Schecterson LC, Bothwell M (2005) Familial Alzheimer's disease mutations inhibit γ-secretase-mediated liberation of β-amyloid precursor protein carboxy-terminal fragment. J Neurochem 94: 1189–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagishita S, Morishima-Kawashima M, Tanimura Y, Ishiura S, Ihara Y (2006) DAPT-induced intracellular accumulations of longer amyloid β-proteins: further implications for the mechanism of intramembrane cleavage by γ-secretase. Biochemistry 45: 3952–3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H et al. (2001) APP processing and synaptic plasticity in presenilin-1 conditional knockout mice. Neuron 31: 713–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Nadeau P, Song W, Donoviel D, Yuan M, Bernstein A, Yankner BA (2000) Presenilins are required for γ-secretase cleavage of β-APP and transmembrane cleavage of Notch-1. Nat Cell Biol 2: 463–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Cui MZ, Mao G, Dong Y, Tan J, Sun L, Xu X (2005) γ-cleavage is dependent on ζ-cleavage during the proteolytic processing of amyloid precursor protein within its transmembrane domain. J Biol Chem 280: 37689–37697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]