Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are crucial in the generation and regulation of adaptive immunity. Given their pivotal role in marshalling immune responses, HIV has evolved ways to exploit DCs to facilitate viral dissemination and to evade antiviral immunity. Defining the mechanisms that underlie cell–cell transmission of HIV and understanding the role of DCs in this process should help us in the fight against HIV infection. This Review highlights the latest advances in our understanding of the interactions between DCs and HIV, and focuses on the mechanisms of DC-mediated viral dissemination.

In 2005, the total number of people living with HIV was estimated to be 40.3 million — the highest level so far — and resulted in 3.1 million deaths from AIDS. Moreover, approximately 4.9 million people became newly infected with HIV in 2005 1, so the fight against HIV infection and transmission has some way to go. Heterosexual transmission is the main route of dissemination of HIV infection worldwide and accounts for 80% of HIV infections 1, 2. Given that dendritic cells (DCs) are located in the mucosa (including oral and vaginal mucosal surfaces) and lymphoid tissues, they are proposed to be among the first cells that encounter HIV type 1 (HIV-1, referred to as HIV from this point) during sexual transmission. It has also been suggested that DCs mediate the spread of HIV to CD4+ T cells in lymphoid tissues in vivo, which are the main source of HIV replication and dissemination (reviewed in 2-6) (FIG. 1). So, understanding the mechanisms of HIV interactions with DCs and cellular receptors will hopefully facilitate the development of more effective interventions against HIV infection and transmission, and potentially aid in the development of novel strategies for the development of HIV vaccines.

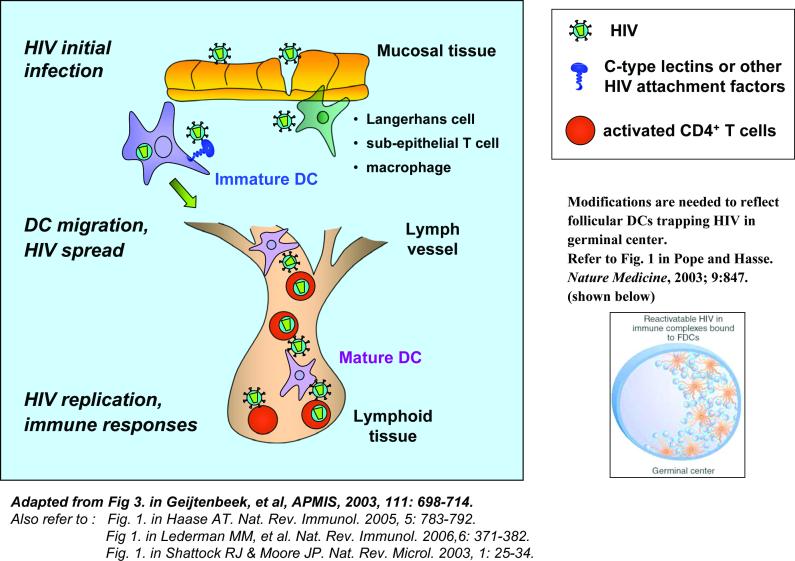

Figure 1.

The role of dendritic cells in HIV infection and viral dissemination.

At mucosal surfaces during the sexual transmission of HIV, dendritic cells (DCs) are proposed to be among the first targets to encounter the virus. These DCs include non-migratory Langerhans cells in epithelial and mucosal tissues, as well as immature myeloid DCs in the submucosa. C-type lectins and/or other viral attachment factors expressed by immature DCs capture HIV and migrate to CD4+ T-cell-enriched lymphoid tissues, where HIV trans-infection of active CD4+ T cells occurs and facilitates viral dissemination. HIV-bearing immature DCs can differentiate into mature DCs by viral infection or by cytokines in the microenvironment during the migration. Mature DCs present HIV antigens to T cells in the lymphoid tissues and initiate viral immune responses. DC-associated HIV may be protected intracellularly from degradation during the migration or retention in the lymphoid tissues. Some DC subsets are susceptible to HIV infection, and subsequently infect neighbouring CD4+ T cells. Follicular DCs (FDCs) in germinal centres can trap large amounts of HIV on their cell surfaces, which provide a stable virus hideaway and also facilitate viral dissemination.

It has been known for more than a decade that HIV-pulsed DCs facilitate viral infection of co-cultured T cells 7, 8. Recent studies of DC–HIV interactions have highlighted an important role for DCs in HIV transmission at mucosal surfaces and in viral pathogenesis. These studies have also revealed several potential mechanisms underlying DC-mediated HIV transmission. One route for viral transfer has been reported to occur through the ‘infectious synapse’ (also termed the ‘virological synapse’)that is formed between DCs and T cells 9, 10; another recently identified pathway suggests that transinfection of HIV may be mediated by DC-derived exosomes 11. Alternatively, infective HIV virions produced in HIV-infected DCs may transmit infection in cis 12-16. Further studies on the significance and relative contributions of these pathways in viral transmission in vivo may shed light on HIV pathogenesis.

This Review focuses on the interactions of HIV with different subsets of DCs, outlining the potential mechanisms of viral dissemination and the relevance to viral immunopathogenesis.

DC subsets and HIV interactions

One of the enigmatic features of DC biology is the complexity of their subsets. Unlike other immune cells, such as T, cell, B cells and natural killer cells, DCs have either a myeloid or lymphoid origin17, 18. In total, DCs are a relatively rare population of cells in the blood or tissues. DC populations can be divided into several subsets based on their anatomical distribution, immunological function and expression of cell-surface markers. The main immunological functions, the susceptibility to HIV infection and their capacity to spread viral infection are summarized for each DC subset, in TABLE 1.

Table 1.

Dendritic-cell subsets and HIV interactions

| Dendritic-cell (DC) subsets |

Anatomical distribution |

Immunological function |

Characteristic markers |

HIV infection |

HIV trans- mission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | |||||

| Myeloid DCs | Blood, cerebrospinal fluid |

Phagocytosis, antigen presentation and DC migration |

CD11c+ CD123− BDCA1 (CD1c) |

Susceptible | Capable |

| Plasmacytoid DCs |

Blood, cerebrospinal fluid, lymphoid nodes |

Antigen capture and presentation, innate and adaptive immune response |

CD123+ CD11c− BDCA2 BDCA4 |

Susceptible | Capable |

| Tissues | |||||

| Langerhans cells |

Epidermis, epithelial tissue of the mucosae |

CD8+ T-cell priming and B- cell activation |

CD1a Langerin (CD207) |

Susceptible | Capable |

BDCA, blood dendritic cell antigen.

DC subsets in vivo

The main DC subsets include myeloid DCs and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) in the blood, and Langerhans cells in the tissues (TABLE 1). Myeloid DCs and pDCs are present at low frequencies, representing 0.5–2% of total peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) 18, 19. In general, myeloid DCs are characterized by their ability to secrete high levels of interleukin-12 (IL-12), whereas pDCs can prime antiviral adaptive immune responses by producing high levels of type 1 interferons 20, 21. Langerhans cells are mainly found in the skin and the stratified squamous epithelia; they comprise 2%–3% of epidermal cells 17, 22. Langerhans cells express langerin (CD207), which is a Langerhans-cell-specific C-type lectin 23.

DCs and HIV infection

Myeloid DCs, pDCs and Langerhans cells are all susceptible to infection with HIV 12, 24-35. Each of the DC subsets express relatively low levels of the HIV receptor CD4, and the co-receptors CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5), CXC-chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), CCR3, CXCR6 (also known as Bonzo, STRL33), CCR8 and CCR9 36-40. Although both myeloid DC and pDC subsets are susceptible to laboratory-adapted R5 and X4 HIV isolates, myeloid DCs are more susceptible to R5 HIV infection than pDCs from the same donor 35. Nevertheless, R5 HIV strains infect myeloid DCs much more efficiently than X4 HIV strains, probably because they express higher levels of CCR5 than CXCR412, 29, 30, 33, 35.

Compared with CD4+ T cells, HIV replication in DCs is generally less productive 5, 12, 30, 31, 33, 44, 45, and the frequency of HIV-infected DCs in vivo is often 10- to 100-fold lower 46. In fact, a study of cells from healthy donors indicated that on average only 1–3% of myeloid DC and pDC populations can be productively infected with HIV in vitro, as detected by intracellular staining of the HIV protein p24 35. A similar low frequency of in vitro HIV infection of Langerhans cells isolated from healthy individuals has also been reported 12. The presumed reasons for moderate HIV infection of DCs include the following: low levels of expression of HIV receptor and co-receptors; rapid and extensive degradation of internalized HIV in intracellular compartments13, 14, 47; and expression of host factor(s) that block HIV replication. An example of such a host factor is the antiretroviral protein APOBEC3G (apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3G), which has been shown to block post-entry HIV replication in resting CD4+ T cells and may be an important innate immune mechanism against retroviral infection 120. Nevertheless, further investigation is required to better understand how DCs restrict productive HIV infection.

Follicular DCs (FDCs) as HIV reservoirs

FDCs are not considered to be a typical DC subset given that they are not derived from the bone marrow and are not known to process and present antigens through MHC-restricted pathways 17, 22. FDCs usually can only be found in the B-cell follicles and germinal centres of peripheral lymphoid tissues. FDCs have the unique capacity to trap pathogens, including HIV, and retain infectious viruses for long periods 48, 49. FDCs can trap and maintain large quantities of HIV early after infection, thereby establishing an insidious reservoir of infectious virus proximal to highly susceptible CD4+ T cells in lymphoid tissues 50,53. Notably, FDCs are not productively infected by HIV; rather, FDCs harbour a large and relative stable pool of virions at their surface48, 49, 51, 52. In addition, FDCs can promote the migration of resting T cells to the germinal-centre microenvironment and this may further facilitate HIV infection of T cells and thereby contribute to HIV pathogenesis 49, 52.

In addition to FDCs, HIV-infected DCs may act as viral reservoirs for persistent infection in vivo. A recent study reported that HIV-infected monocyte-derived DCs (MDDCs) could productively replicate viruses for up to 45 days 54. However, it remains to be determined whether DCs can provide a cellular reservoir for latent infection, and whether they could be a potential target for eradication of the virus.

Monocyte-derived DCs as an in vitro model

Due to the low abundance of DC populations in vivo, to model the immunological function of DCs and study DC–HIV interactions, MDDCs are commonly used in experimental studies in vitro 55. CD14+ monocytes from human peripheral blood differentiate into immature DCs after 4–6 days in culture in the presence of IL-4 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). MDDCs share characteristics with myeloid DCs, immature dermal DCs and interstitial DCs, and they express high levels of the cell-surface markers MHC class II molecules, CD11c, CD25 and DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3 (ICAM3)-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN; also known as CD209) 56. Immature MDDCs can be converted into mature MDDCs by various stimuli, including lipopolysaccharide, interferon-γ, tumour-necrosis factor and CD40 ligand (FIG. 2) 17, 22, 57. It has been observed that different stimuli used to engender DC maturation may result in the generation of DCs with distinct HIV transmission abilities 58.

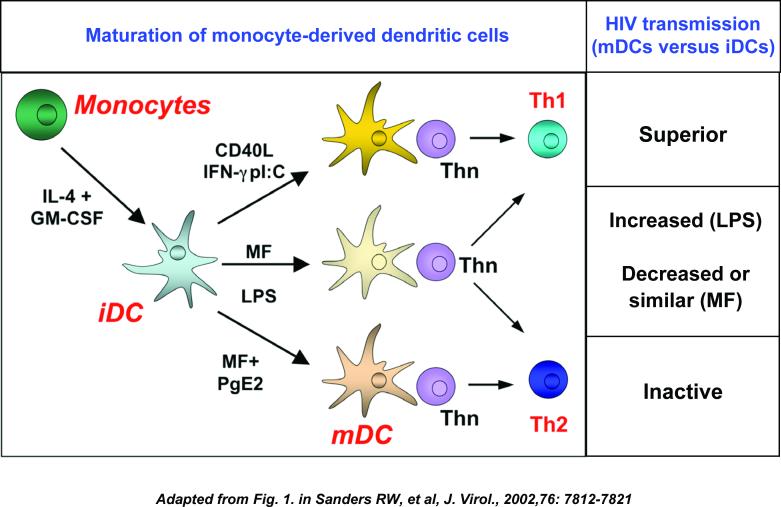

Figure 2.

Dendritic-cell maturation affects HIV transmission.

Monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells (DCs) develop into T helper 1 (TH1)-cell-promoting or TH2-cell-promoting effector subsets, depending on the activation signal they receive. CD14+ monocytes are cultured in the presence of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) to develop into immature DCs, which can be further cultured with diverse stimuli to obtain different mature DC subtypes. Polarization of TH-cell function by mature DC subsets is depicted. Compared with immature DCs, HIV transmission to CD4+ T cells significantly varies in different mature DC subsets. CD40L: CD40 ligand; IFNγ: interferon-γ; poly I-C, polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid; MF: maturation factors such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumour-necrosis factor (TNF); LPS: lipopolysaccharide; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; TH0: naïve T helper cells.

Despite their convenience, MDDCs do not fully mimic the immunological function of DC subsets in HIV infection in vivo 38, 59-61. Therefore, experimental observations made using MDDCs and the physiological implications drawn from such studies should be interpreted carefully. For example, C-type lectins expressed on the surface of MDDCs accounted for more than 80% of the binding to HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120, however, freshly isolated and cultured blood DCs only bind gp120 through CD4 and not through C-type lectins 38. So, although MDDCs have provided insights into DC biology and HIV interactions, examination of bona fide DC subsets in vivo for HIV capture, transmission and antigen-processing pathways would be beneficial for understanding of the true contribution of DCs to viral pathogenesis.

Immunomodulation of DCs by HIV infection

Modulation of DCs by HIV infection, in particular by modulation or interference of the antigen-presenting function of DCs, is a key aspect in viral pathogenesis and contributes to viral evasion of immunity. Compared with DCs from healthy donors, DCs derived from the peripheral blood of HIV-infected individuals at different stages of infection have significantly reduced efficiency in stimulating allogeneic T cells 62, 63. It has been reported that DC-SIGN+ DCs in acute HIV infection have reduced expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, and this may influence DC-induced T-cell responses 64. Consistent with this, HIV-infected MDDCs43 and myeloid DCs67 fail to mature in culture, and may stimulate production of the regulatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10) by T cells, thereby promoting an immunosuppressive response43. These results suggest that productive HIV infection of myeloid DCs undermines the direct induction of T-cell-mediated immunity. By contrast, some studies have indicated that MDDCs from HIV-infected individuals can efficiently induce CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses to various antigens 65, 66, suggesting that modulation of expression of co-stimulation molecules by HIV-infected DCs might not necessarily subvert the priming of CTLs by DCs. In addition, Smed-Sorensen et al. did not observe functional defects in cytokine production following stimulation of HIV-infected myeloid DCs and pDCs 35.

HIV regulatory and accessory proteins, such as Nef and Tat, have been reported to have various effects on immature DCs, although again the results are not always consistent. Messmer and colleagues reported that expression of adenovirus-vector-encoded Nef by immature MDDCs triggers the production of various cytokines and chemokines and stimulates T-cell activation, but this occurs without upregulating the expression of DC maturation markers 68. Similarly, HIV infection or adenovirus-vector-mediated expression of Tat by immature DCs can induce interferon-responsive gene expression without inducing DC maturation71. By contrast, exposure to recombinant (Escherichia coli-expressed) Nef or Tat protein led to efficient DC maturation, including upregulation of expression of DC maturation markers 69, 70. Tat may have a role in viral pathogenesis, by inducing the production of T-cell and macrophage chemoattractants by immature DCs, and thereby may facilitate the spread of HIV infection 71. Last, Nef protein can downregulate the expression of MHC class I and CD1a molecules by immature MDDCs 72,73, which may impair antigen presentation and contribute to immune evasion of HIV.

DCs transmit HIV to CD4+ T cells

Using the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and a rhesus macaque intravaginal transmission model, several studies have suggested that SIV can rapidly penetrate the vaginal mucosa after viral exposure and then infects or associates with intraepithelial DCs, which can mediate viral transmission to CD4+ T cells 75-77. In one study of human cervical explants exposed to HIV, it was shown that migratory DC populations from the cervical tissue account for 90% of HIV dissemination 78. These results suggest that DCs may play an important role in HIV transmission from mucosal surfaces 2, 4. Langerhans cells in the mucosal epithelium have been proposed to be initial targets for HIV infection by sexual transmission 29, although this remains controversial. In addition to these Langerhans cells and immature DCs in the subepithelial mucosal tissues, CD4+ CCR5+ T cells and macrophages that reside in the subepithelium might also be early targets for HIV infection and transmission in vivo (reviewed in 2,79).

The transfer of virus from DCs to CD4+ T cells involves three discrete steps. First, DCs bind and capture HIV, the virus then traffics within the DC, before it is transferred to the CD4+ T cells in a process known as trans-infection. In the following section, we consider HIV trans-infection mediated by DCs that are not themselves infected and later we discuss the transfer of progeny virus from infected DCs to T cells, a process known as cis-infection.

Capture of HIV by DCs

DCs have a unique membrane transport pathway that facilitates the uptake pathogens to initiate adaptive immune responses. DCs constitutively take up extracellular fluid by macropinocytosis, and engulf antigens and whole pathogens by endocytosis and phagocytosis mediated by expression of Fc receptors and C-type lectins, such as DC-SIGN 17, 22, 56. C-type lectins are the main HIV attachment factors expressed by dermal and mucosal DCs. Four types of C-type lectin can bind to HIV gp120: DC-SIGN, langerin (CD207), mannose receptor (CD206) and an unidentified trypsin-resistant C-type lectin 38, 59; no single C-type lectin is fully responsible for HIV binding on all DC subsets. Binding of gp120 to DCs migrating from the tonsils seems to be CD4 dependent. By contrast, HIV capture by Langerhans cells is partly mediated by langerin 59. For DC-SIGN-dependent HIV binding, interactions between gp120 and the carbohydrate-recognition domain of DC-SIGN are required for virus capture 80, 81 (Box 1).

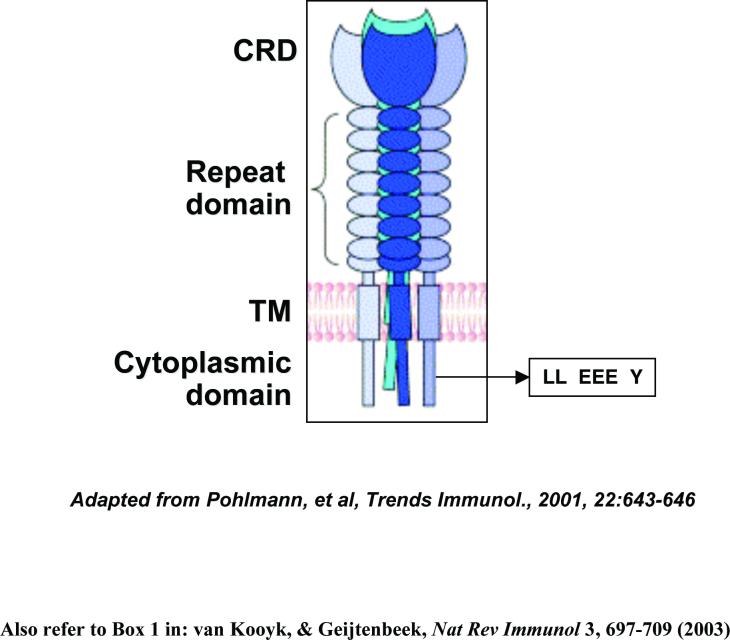

Box 1 DC-SIGN structure and interactions with HIV.

DC-SIGN (dendritic cell (DC)-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin) is a C-type lectin (calcium dependent) 56, 127. Human DC-SIGN expression in vivo has been reported in DCs 56, 87, 88, 93, 100, macrophages 61, 84, 93, 94, activated B cells128, the skin dermis 56, 59, placenta 99, intestinal and genital mucosae 88, 100, and lymphoid tissues 56, 61, 64, 101, 129. Interaction of the carbohydrate-recognition domain (CRD) of DC-SIGN with the HIV envelope (Env) glycoprotein gp120 is required for virus binding 80. CRD interactions with HIV depend on the high proportion of high-mannose oligosaccharides present in the Env glycoproteins 81, 130, 131. DC-SIGN functions as a tetramer. This multimerization depends on repeated sequences in the extracellular neck repeat domain, which stabilizes tetramers of DC-SIGN and increases ligand-binding avidity 130, 132.

The cytoplasmic tail of DC-SIGN contains three defined internalization motifs, a dileucine (LL)-based motif, a tri-acidic (EEE) cluster and a tyrosine (Y)-based motif. These motifs may contribute to DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of HIV 131. DC-SIGN-bound HIV can enter cells by endocytosis, some viruses may escape degradation in lysosomal compartments and usurp endosomal trafficking in transmission to CD4+ T cells, resulting in productive HIV trans-infection 11, 97. DC-SIGN facilitates the uptake of viral antigens for MHC-class-I- and MHC-class-II-restricted antigen presentation, leading to activation of antiviral-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells 47, 115. HIV Nef can upregulate DC-SIGN expression by DCs and enhances clustering of DCs with T cells, which promotes HIV trans-infection 133. The figure is modified with permission from REF. Pohlmann et al. Trends Immunol. 22, 643-646 (2001) Elsevier B.V. © 2001.

DC-SIGN-mediated HIV transmission seems to require steps beyond simple virus binding and sequestration 82, 83, suggesting that DC-SIGN binding and transfer functions can be dissociated. So, despite identification of endogenous expression of DC-SIGN or other C-type lectins by several cell types in vivo, these cells may not be able to support HIV trans-infection. DC-SIGN expression has been shown to increase direct HIV infection of DC-SIGN-transfected cells 84, 85, but may inhibit HIV Env-mediated cell-cell fusion 86, suggesting that competition between CD4 and DC-SIGN for binding to gp120 probably affects the access of the virus to the cytosol and the formation of syncytia.

Transfer of captured HIV by DCs

A molecular clue to DC-mediated HIV transmission was provided by studies of DC-SIGN-expressing cells 56, 80. A subset of cells in human blood (0.01% of total PBMCs) was isolated on the basis of co-expression of DC-SIGN and the monocytic marker CD14; these DC-like cells were reported to be able to increase HIV trans-infection of T cells 87. Similarly, Gurney et al. reported that DC-SIGN-expressing cells that were isolated from the rectal mucosa and that seemed to have an immature phenotype could efficiently bind and transfer HIV to CD4+ T cells 88. These DC-SIGN+ cells comprise only 1–5% of total mucosal mononuclear cells, but they were shown to contribute more than 90% of virus binding. Binding of HIV was mainly mediated by DC-SIGN, as DC-SIGN-specific antibodies could block virus binding, when more physiological amounts of virus were inoculated 88.

Although initial observations suggested that DC-SIGN is exclusively expressed by DCs to enhance HIV trans-infection and to stimulate T-cell responses 56, 80, subsequent studies have indicated that DCs also have DC-SIGN-independent mechanisms of HIV trans-infection of CD4+ T cells 61, 85, 89-92. Blockade of DC-SIGN with specific antibodies and small interfering RNAs indicated that MDDCs and blood myeloid DCs do not require DC-SIGN to transmit HIV 61. Moreover, DC-SIGN is abundantly expressed by macrophages rather than by DCs in normal human lymph nodes 61. High levels of DC-SIGN expression by macrophages in lymph tissues or in the blood suggests that it might aid in HIV trans-infection by macrophages in vivo 61, 84, 93, 94; however, this is yet to be confirmed. Notably, similar to MDDCs, human monocyte-derived macrophages show DC-SIGN-independent HIV transmission 95, 96, possibly involving other C-type lectin molecules, such as the mannose receptor.

HIV trafficking in DCs seems to be a critical step in viral transmission and may also be DC-SIGN independent. Kwon and colleagues observed that HIV that was internalized after DC-SIGN binding retained infectivity and could be transmitted to target CD4+ T cells 97. DC-SIGN mediates rapid internalization of intact HIV into a low pH, nonlysosomal compartment 97. However, it is not clear whether internalized HIV virions continue to associate with DC-SIGN and whether DC-SIGN mediates recycling of intact viruses back to the cell surface. The precise intracellular trafficking and localization of internalized HIV within DCs remains to be elucidated.

DC-SIGN-mediated HIV transmission is cell-type dependent 83, 85, 98 and requires cell-cell contact 83. Interestingly, B-cell transfectants expressing DC-SIGN mediate HIV-trans-infection as efficiently as DCs, whereas monocytic transfectants do not 98. In related studies, we observed that co-cultures of different cell types may interfere with DC-SIGN-mediated HIV trans-infection83. These findings reinforce the notion that the cellular environment is an important consideration when examining transmission of HIV captured by DC-SIGN or other attachment factors.

Despite the detection of DC-SIGN expression by DCs in different human tissues 56, 61, 64,88, 93, 99-101, none of the DC subsets myeloid DCs, pDCs, Langerhans cells and FDCs have been clearly shown to express DC-SIGN in vivo 33, 38, 56, 59, 61, 102, suggesting that the role of DC-SIGN in DC-mediated HIV transmission may be more limited in vivo. Some submucosal DC populations at sites of initial HIV infection are DC-SIGN-positive and seem to interact with HIV quite efficiently 59, 88, 100. However, given that they reside beneath the mucosal epithelium, in the absence of breaches in the mucosal barrier, DC-SIGN-expressing cells are unlikely to be the first cells to contact HIV in vivo. Thus, the importance of HIV dissemination by DCs and the role of DC-SIGN in the transmission process remain unclear, particularly in vivo.

Role of DC maturation in HIV transmission and replication

Unlike mature DCs, immature myeloid DCs are specialized to take up antigens at sites of infection. Following capture of antigens, immature DCs traffic to lymphoid tissues where they develop into mature DCs, which are potent stimulators of naive T cells owing upregulation of expression of MHC class II and co-stimulation molecules 17, 22 (TABLE 2).

Table 2.

Distinct HIV interactions with immature and mature dendritic cells (DCs)

| Features | Immature DCs | Mature DCs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Anatomical localization |

Mucosa, peripheral tissues | Secondary lymphoid tissues |

17, 22 |

|

Immunological function |

Capture and process antigen |

Present antigen, prime T cells |

17, 22 |

| HIV interactions | |||

| Viral fusion | Occurs (but less efficient than CD4+ T cells) |

Decreased and kinetically slowed |

104 |

| Replication | Productive (but slower and less efficient than active CD4+ T cells) |

10-100-fold lower; post-integration inhibition |

30, 31, 105, 134 |

| Intracellular accumulations of virion |

Less virions | 15-fold more viral DNA, much more virions |

42, 106 |

| Transmission to CD4+ T cells |

Efficient, partially dependent on DC-SIGN |

Highly efficient and independent of DC- SIGN * |

9, 58, 61, 90-92, 103 |

L.W. and V.N.K., unpublished observations.

HIV transmission efficiency can be enhanced by maturation of DCs9, 30, 58, 103, suggesting that mature DCs in lymphoid tissues may facilitate infection of lymphoid-tissue-resident CD4+ T cells. However, the mechanisms underlying this increased viral transmission have not been well defined. Downmodulation of antigen uptake and degradation in mature DCs, as well as more efficient interactions between mature DCs and T cells may contribute to the enhanced HIV transmission efficiency 9, 58. Depending on the activating signals they receive, immature DCs can develop into different subsets of mature DCs with differing capabilities in HIV transmission and T-cell activation58. Increased ICAM1 expression correlates with the increased viral transmission by mature DC subsets, possibly due to stronger DC-T-cell interactions through ICAM1 binding to T-cell-expressed leukocyte function-associated molecule 1 (LFA1) 58 (FIG. 2). Moreover, different cellular trafficking of HIV within immature DCs and mature DCs may also contribute to differences in HIV transmission potential (L.W. and V.N.K., unpublished observations). Consistent with this, mature DCs have been reported to contain high levels of intact virions in large vesicular compartments with a perinuclear localization, whereas immature DCs retain few intact virus particles in endosomes close to the plasma membrane 106.

DC maturation is associated with a diminished ability to support HIV replication, being 10- to 100-fold lower than immature DCs 30, 42 (TABLE 2). But, HIV-pulsed mature DCs have been shown to contain 15-fold more viral DNA than immature DCs, which initially suggested that virus entry was not impaired 42. However, a recent study indicated that the defect in HIV replication observed in mature DCs results at least partially from decreased viral fusion 104. By analysing the phases of viral replication, Bakri et al. reported that DC maturation does not affect HIV reverse transcription, nuclear import and integration, suggesting that the reduced viral replication in mature DCs is due to post-integration blocks at the transcriptional level 105. This might account for the high levels of viral DNA detected in mature cells but their inefficient release of viral virions.

Mechanisms underlying DC-mediated HIV transmission

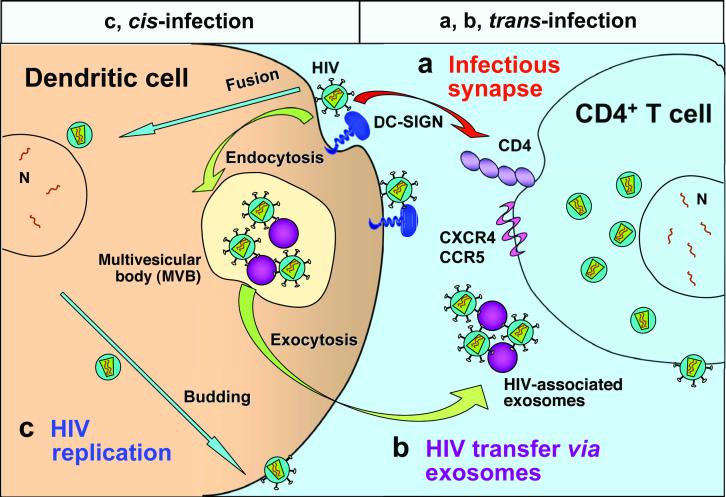

Current evidence suggests that DC-mediated HIV infection can occur by several distinct and co-existing processes. These processes include trans-infection through infectious synapses and exosome-associated viruses, as well as cis-infection following de novo viral production in DCs (FIG. 3).

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of dendritic-cell-mediated HIV transmission. Two types of dendritic cell (DC)-mediated HIV transmission have been proposed, namely, trans- and cis-infection of DCs. Trans-infection of DCs includes two pathways: (a). HIV transmission across the infectious synapse. DCs transfer captured HIV to target CD4+ T cells through the cell-cell junctions known as infectious synapses. DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN) participates in formation of the infectious synapse. (b). Exocytotic pathway of HIV-bearing exosomes. Endocytosed HIV can gain access to endosomal multivesicular bodies (MVBs), enabling release as exosome-associated viruses. Exosome-associated HIV particles are likely to be transmitted to CD4+ T cells through membrane binding and fusion. Cis-infection: (c). After the initial viral exposure, HIV infection and replication in DCs results in de novo viral production and long-term transmission. It is conceivable that these three mechanisms coexist in vitro, however, the relative importance of these pathways in vivo remains to be investigated. CCR5, CC chemokine receptor 5; CXCR4, CXC chemokine receptor 4.

HIV trans-infection through infectious synapses

Previous studies with MDDCs indicated that cell–cell contact is required for efficient stimulation of CD4+ T-cell infection 108. More recently studies have revealed that HIV transmission may occur across the infectious or virological synapse 9, 10, 13, 109. The structure of the infectious synapse may have similarities to the immunological synapse, which is formed between antigen-presenting cells and their T-cell conjugates 110. The cell-surface molecules that contribute to the infectious synapse and potentially support the transfer of HIV from DCs to CD4+ T cells have not been completely identified. HIV itself and viral receptors are found concentrated at the infectious synapse and DC-SIGN molecules are also detected 10, 109; however, it is unclear whether these or any other molecules are essential to promote formation of the infectious synapse. Interestingly, suppression of DC-SIGN expression has been shown to impair the infectious synapse formation, and to inhibit trans-infection of X4 HIV to T cells 10, 107. We have reported that the expression of MHC class II molecules on virus donor cells are not required for efficient DC-SIGN-mediated HIV transmission 83, suggesting that virus transmission to CD4+ T cells can occur in the absence of the classically defined immunological synapse. Indeed, human fibroblasts expressing HIV receptors can serve as effective target cells for DC- or DC-SIGN-mediated HIV transmission 90, 97; and an earlier study has shown that even DCs from mice (which can not be infected with HIV) are able to transmit HIV to human T cells 7. These results suggest that the donor- and target-cell requirements for infectious synapse formation are minimal. Under conditions with large virus inoculums and in cells placed in T-cell co-cultures soon after exposure to HIV, it is likely that infectious-synapse-mediated HIV transfer is responsible for most of the rapid and efficient viral transfer between DCs and CD4+ T cells in vitro. However, in vivo, it is likely that different mechanisms of transmission also contribute or even predominate.

HIV trans-infection through exosomes

Wiley and Gummuluru recently showed that DC-derived exosomes can mediate HIV trans-infection 11. HIV captured by immature MDDCs11 and mature MDDCs109 is rapidly internalized into endosomal multivesicular bodies (MVBs), which are endocytic bodies that are enriched with tetraspanin proteins. Intriguingly, some of the endocytosed HIV particles are constitutively released into the extracellular milieu in endocytic vesicles (known as exosomes)111, which can fuse with target-cell membranes to deliver infectious virus. The infectious virus associated with cell-free exosomes is a fraction of the virus measured during synaptic transmission, but, importantly, they may provide a pathway by which intracellular virus reaches the infectious synapse. The remaining MVB-resident HIV in DCs may enter the lysosomal pathway and be degraded. Therefore, the exosome-release pathway may enable HIV to circumvent immune destruction after capture by DCs. Although further study is required, it is intriguing to note that the exosome-associated HIV particles released from immature MDDCs have been reported to be 10-fold more infectious than cell-free viruses on a per-particle basis 11.

In productively infected macrophages, endocytosis and exosome trafficking pathways may be used for HIV particle assembly and release112,113,114. It will be interesting to determine whether in vivo DC subsets of myeloid DCs, pDCs and Langerhans cells also use the exosomal pathway to promote HIV trans-infection. The relative importance of this pathway of trans-infection remains to be established compared with the infectious-synapse-mediated pathway.

HIV cis-infection by viral replication in DCs

Although direct HIV infection is less efficient in DCs than in CD4+ T cells 30, 42, increasing evidence indicates that long-term HIV transmission mediated by DCs depends on viral production by the DCs. It has been reported that immature DCs and some DC-SIGN-expressing cell lines can retain infectious virus for up to 6 days after exposure to HIV41, 80, 85. However, recent studies have indicated that most incoming viruses are degraded in MDDCs within 24 hours13, 47, 115. Therefore, after 24 hours, virus that is transmitted from DCs to T cells must be newly synthesized progeny virus. So, two phases of DCs transfer of HIV to CD4+ T cells might exist13: the first phase (within 24 hours after exposure to HIV) might involve trafficking of captured virus from the endolysosomal pathway to the DC–T-cell synapse; the second phase (24-72 hours after viral exposure) would involve de novo replication of virus in DCs. It should be pointed out that these two processes are not necessarily sequential or interdependent.

Other recent findings also support the need for HIV replication in DCs for long-term viral transmission 14, 16. Nobile and colleagues reported that transfer of incoming virions from immature MDDCs or DC-SIGN-expressing cells occurs only within a few hours after viral exposure, indicating that there is no long-term storage of original infectious HIV particles in these cells. However, a few days after viral exposure, replicative viruses can also be transmitted to CD4+ cells by infected DCs14. Similar to these studies withMDDCs, Lore and colleagues reported that soon after HIV exposure, pDCs and myeloid DCs from human blood can transfer the virus to T cells in the absence of a productive infection. However, once a productive infection is established in the DCs, newly synthesized virus is predominantly spread to T cells 15. These results indicate that HIV-infected DCs in vivo may act as viral reservoirs during the migration to the lymphoid tissues to spread viral infection.

Both phases are likely to contribute to in vivo transfer of virus from DCs to T cells; however, given the low levels of HIV replication in DCs and the low frequency of DCs in vivo, the significance of DC transmission of de novo synthesized virus in vivo remains to be examined. Our in vitro results with replication-defective, single-cycle reporter HIV suggest that viral transmission can occur efficiently in the absence of viral replication 9, 83, 89, 90, 98. So, rare HIV replication in DCs may not be necessary to facilitate viral dissemination if the immediate viral transfer has been established through infectious synapses.

Future directions

In opposition of immune sentinel function of DCs to capture and present processed pathogens, HIV hijacks DCs to efficiently promote viral dissemination. Elucidating HIV interactions with DCs will be vital in uncovering their contribution to HIV pathogenesis. An improved understanding of DC biology may also facilitate studies of DC interactions with HIV and other human pathogens. It will be crucial to dissect and compare the viral antigen processing and presentation pathways in HIV-infected DCs and in DCs bearing internalized virions. In addition, the type and tissue source of DCs from humans and non-human primate models will be an important consideration in these analyses. Because CD4+ T-cell populations in the gastrointestinal tract suffer the most marked depletion in both acute and chronic stages of HIV infection 116, 117, it will be critical to characterize DC populations in the gastrointestinal tract for their susceptibility to HIV infection and ability to promote viral transmission to CD4+ T cells in gut mucosa.

Viral assembly and budding from infected DCs is a poorly understood area of HIV research that also requires further study. An early study reported that new HIV virions could bud from the surface of infected MDDCs, although this was a rare finding 28. In infected macrophages, MVB-like compartments seem to be important for viral assembly and budding112, 113, 121, but in infected DCs, the involvement of these compartments remains to be proven.

Although in this review we have focused on the role of DCs in the dissemination of virus and how HIV may hijack DC functions to their advantage, DCs are of course potent stimulators of immune responses and therefore have been used in prophylactic and therapeutic approaches for HIV infection. For example, transfer of autologous MDDCs loaded with the inactivated, whole HIV was shown to suppress viral load in individuals chronically infected with HIV125. By contrast, a pilot clinical trial using HIV-peptide-pulsed DCs did not show significant therapeutic effects in six HIV-infected patients 126. So, further investigation of the antiviral immune responses induced by the inactivated-HIV-loaded DCs will be critical to understand the correlates underlying the therapeutic effects.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. J. Barbieri for critical reading of the manuscript. L.W. is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH, United States) and the Research Affairs Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. V.N.K is supported by the intramural research funds from the NIH. The authors apologize to all colleagues whose work has not been cited in this review due to space restrictions.

Glossary

- C-type lectins

A family of transmembrane proteins (Ca2+ dependent activities) that act as cell-adhesion receptors. C-type lectins are involved in the regulation of signalling pathways and recognize specific carbohydrate structures of pathogens and self-antigens.

- Infectious synapse (virological synapse)

The cell-cell contact zone between dendritic cells and T cells that facilitates transmission of HIV by locally concentrating virus and viral receptors.

- Trans-infection

Monocyte-derived dendritic cells and DC-SIGN transfectants can capture and transfer HIV to target cells without themselves becoming infected. This allows transfer of virus from a cell type that captures, but does not become infected, via DC-SIGN or other HIV attachment factors.

- Exosomes

Small lipid-bilayer vesicles that are released from dendritic cells and other cells. They are composed of cell membranes or are derived from the membranes of intracellular vesicles. They might contain antigen–MHC complexes and interact with antigen-specific lymphocytes directly, or they might be taken up by other antigen-presenting cells.

- R5 Virus

An HIV strain that uses CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) as the co-receptor to gain entry to target cells.

- X4 Virus

An HIV strain that uses CXC-receptor 4 (CXCR4) as the co-receptor to gain entry to target cells.

- Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)

Collectively, different HIV-related lentiviruses isolated from nonhuman primates. SIV infection of rhesus macaque provides an experimental model for HIV-1 infection in humans.

- MACROPINOCYTOSIS

An actin-dependent process by which cells engulf large volumes of fluids.

- Immunological synapse

A large junctional structure that is formed at the cell surface between a T cell and an antigen-presenting cell. Important molecules involved in T-cell activation — including the T-cell receptor, numerous signal-transduction molecules and molecular adaptors — accumulate in an orderly manner at this site. Mobilization of the actin cytoskeleton of the cell is required for immunological-synapse formation.

- Multivesicular body (MVB)

An endocytic organelle that contains small vesicles generated from budding of an endosomal membrane into the lumen of the compartment.

- Cross-presentation (or cross-priming)

The ability of certain antigen-presenting cells to take up, process and present extracellular antigens with MHC-class-I molecules to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the absence of de novo synthesis of protein antigens.

- Tetraspanins

A family of transmembrane proteins that have transmembrane and extracellular domains of different sizes. Their function is not known clearly, but they seem to interact with many other transmembrane proteins and to form large multimeric protein networks, which might be involved in intracellular signalling.

References

- 1.UNAIDS AIDS Epidemic Update. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shattock RJ, Moore JP. Inhibiting sexual transmission of HIV-1 infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;1:25–34. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reece JC, et al. HIV-1 selection by epidermal dendritic cells during transmission across human skin. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1623–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope M, Haase AT. Transmission, acute HIV-1 infection and the quest for strategies to prevent infection. Nat. Med. 2003;9:847–52. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinman RM, et al. The interaction of immunodeficiency viruses with dendritic cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003;276:1–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-06508-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haase AT. Perils at mucosal front lines for HIV and SIV and their hosts. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:783–92. doi: 10.1038/nri1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron PU, et al. Dendritic cells exposed to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells. Science. 1992;257:383–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1352913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pope M, et al. Conjugates of dendritic cells and memory T lymphocytes from skin facilitate productive infection with HIV-1. Cell. 1994;78:389–98. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald D, et al. Recruitment of HIV and its receptors to dendritic cell-T cell junctions. Science. 2003;300:1295–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1084238. The first paper to describe HIV infectious synapses between DCs and T cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arrighi JF, et al. DC-SIGN-mediated infectious synapse formation enhances X4 HIV-1 transmission from dendritic cells to T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1279–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiley RD, Gummuluru S. Immature dendritic cell-derived exosomes can mediate HIV-1 trans infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:738–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507995103. A recent paper describing the exosome-mediated HIV trans-infection by immature monocyte-derived DCs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawamura T, et al. R5 HIV productively infects Langerhans cells, and infection levels are regulated by compound CCR5 polymorphisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:8401–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turville SG, et al. Immunodeficiency virus uptake, turnover, and 2-phase transfer in human dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;103:2170–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3129. A paper reporting the immediate and long-term HIV transmission by monocyte-derived human DCs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nobile C, et al. Covert human immunodeficiency virus replication in dendritic cells and in DC-SIGN-expressing cells promotes long-term transmission to lymphocytes. J. Virol. 2005;79:5386–99. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5386-5399.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lore K, Smed-Sorensen A, Vasudevan J, Mascola JR, Koup RA. Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells transfer HIV-1 preferentially to antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:2023–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burleigh L, et al. Infection of dendritic cells (DCs), not DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of human immunodeficiency virus, is required for long-term transfer of virus to T cells. J. Virol. 2006;80:2949–2957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2949-2957.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banchereau J, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu YJ. Dendritic cell subsets and lineages, and their functions in innate and adaptive immunity. Cell. 2001;106:259–62. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rissoan MC, et al. Reciprocal control of T helper cell and dendritic cell differentiation. Science. 1999;283:1183–6. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cella M, et al. Plasmacytoid monocytes migrate to inflamed lymph nodes and produce large amounts of type I interferon. Nat. Med. 1999;5:919–23. doi: 10.1038/11360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegal FP, et al. The nature of the principal type 1 interferon-producing cells in human blood. Science. 1999;284:1835–7. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valladeau J, et al. The monoclonal antibody DCGM4 recognizes Langerin, a protein specific of Langerhans cells, and is rapidly internalized from the cell surface. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:2695–704. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199909)29:09<2695::AID-IMMU2695>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niedecken H, Lutz G, Bauer R, Kreysel HW. Langerhans cell as primary target and vehicle for transmission of HIV. Lancet. 1987;2:519–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91843-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger R, et al. Isolation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from human epidermis: virus replication and transmission studies. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1992;99:271–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12616619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soto-Ramirez LE, et al. HIV-1 Langerhans' cell tropism associated with heterosexual transmission of HIV. Science. 1996;271:1291–3. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludewig B, Gelderblom HR, Becker Y, Schafer A, Pauli G. Transmission of HIV-1 from productively infected mature Langerhans cells to primary CD4+ T lymphocytes results in altered T cell responses with enhanced production of IFN-gamma and IL-10. Virology. 1996;215:51–60. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blauvelt A, et al. Productive infection of dendritic cells by HIV-1 and their ability to capture virus are mediated through separate pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:2043–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI119737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaitseva M, et al. Expression and function of CCR5 and CXCR4 on human Langerhans cells and macrophages: implications for HIV primary infection. Nat. Med. 1997;3:1369–75. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granelli-Piperno A, Delgado E, Finkel V, Paxton W, Steinman RM. Immature dendritic cells selectively replicate macrophagetropic (M-tropic) human immunodeficiency virus type 1, while mature cells efficiently transmit both Mand T-tropic virus to T cells. J. Virol. 1998;72:2733–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2733-2737.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granelli-Piperno A, Finkel V, Delgado E, Steinman RM. Virus replication begins in dendritic cells during the transmission of HIV-1 from mature dendritic cells to T cells. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:21–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawamura T, et al. Candidate microbicides block HIV-1 infection of human immature Langerhans cells within epithelial tissue explants. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1491–500. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patterson S, Rae A, Hockey N, Gilmour J, Gotch F. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are highly susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and release infectious virus. J. Virol. 2001;75:6710–3. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6710-6713.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donaghy H, et al. Loss of blood CD11c(+) myeloid and CD11c(−) plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients with HIV-1 infection correlates with HIV-1 RNA virus load. Blood. 2001;98:2574–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smed-Sorensen A, et al. Differential susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2005;79:8861–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8861-8869.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granelli-Piperno A, et al. Efficient interaction of HIV-1 with purified dendritic cells via multiple chemokine coreceptors. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:2433–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubbert A, et al. Dendritic cells express multiple chemokine receptors used as coreceptors for HIV entry. J. Immunol. 1998;160:3933–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turville SG, et al. HIV gp120 receptors on human dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;98:2482–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ignatius R, et al. The immunodeficiency virus coreceptor, Bonzo/STRL33/TYMSTR, is expressed by macaque and human skin- and blood-derived dendritic cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2000;16:1055–9. doi: 10.1089/08892220050075318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beaulieu S, et al. Expression of a functional eotaxin (CC chemokine ligand 11) receptor CCR3 by human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2002;169:2925–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petit C, et al. Nef is required for efficient HIV-1 replication in cocultures of dendritic cells and lymphocytes. Virology. 2001;286:225–36. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canque B, et al. The susceptibility to X4 and R5 human immunodeficiency virus-1 strains of dendritic cells derived in vitro from CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells is primarily determined by their maturation stage. Blood. 1999;93:3866–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Granelli-Piperno A, Golebiowska A, Trumpfheller C, Siegal FP, Steinman RM. HIV-1-infected monocyte-derived dendritic cells do not undergo maturation but can elicit IL-10 production and T cell regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:7669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402431101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cameron PU, Forsum U, Teppler H, Granelli-Piperno A, Steinman RM. During HIV-1 infection most blood dendritic cells are not productively infected and can induce allogeneic CD4+ T cells clonal expansion. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1992;88:226–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pope M, Gezelter S, Gallo N, Hoffman L, Steinman RM. Low levels of HIV-1 infection in cutaneous dendritic cells promote extensive viral replication upon binding to memory CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1995;182:2045–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McIlroy D, et al. Infection frequency of dendritic cells and CD4+ T lymphocytes in spleens of human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J. Virol. 1995;69:4737–45. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4737-4745.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moris A, et al. DC-SIGN promotes exogenous MHC-I-restricted HIV-1 antigen presentation. Blood. 2004;103:2648–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tenner-Racz K, et al. Immunohistochemical, electron microscopic and in situ hybridization evidence for the involvement of lymphatics in the spread of HIV-1. AIDS. 1988;2:299–309. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198808000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heath SL, Tew JG, Szakal AK, Burton GF. Follicular dendritic cells and human immunodeficiency virus infectivity. Nature. 1995;377:740–4. doi: 10.1038/377740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burton GF, Keele BF, Estes JD, Thacker TC, Gartner S. Follicular dendritic cell contributions to HIV pathogenesis. Semin. Immunol. 2002;14:275–84. doi: 10.1016/s1044-5323(02)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spiegel H, Herbst H, Niedobitek G, Foss HD, Stein H. Follicular dendritic cells are a major reservoir for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in lymphoid tissues facilitating infection of CD4+ T-helper cells. Am. J. Pathol. 1992;140:15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith BA, et al. Persistence of infectious HIV on follicular dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2001;166:690–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schacker T, et al. Rapid accumulation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in lymphatic tissue reservoirs during acute and early HIV infection: implications for timing of antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181:354–7. doi: 10.1086/315178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Popov S, Chenine AL, Gruber A, Li PL, Ruprecht RM. Long-term productive human immunodeficiency virus infection of CD1a-sorted myeloid dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2005;79:602–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.602-608.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romani N, et al. Proliferating dendritic cell progenitors in human blood. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:83–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geijtenbeek TB, et al. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell. 2000;100:575–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80693-5. This paper and Ref. 80 report the identification of DC-SIGN and characterization of DC-SIGN function in enhancing HIV trans-infection. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Jong EC, et al. Microbial compounds selectively induce Th1 cell-promoting or Th2 cell-promoting dendritic cells in vitro with diverse Th cell-polarizing signals. J. Immunol. 2002;168:1704–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanders RW, et al. Differential transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by distinct subsets of effector dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2002;76:7812–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7812-7821.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turville SG, et al. Diversity of receptors binding HIV on dendritic cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:975–83. doi: 10.1038/ni841. This article characterizes a variety of HIV-binding receptors on DC subsets. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jefford M, et al. Functional comparison of DCs generated in vivo with Flt3 ligand or in vitro from blood monocytes: differential regulation of function by specific classes of physiologic stimuli. Blood. 2003;102:1753–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Granelli-Piperno A, et al. Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin/CD209 is abundant on macrophages in the normal human lymph node and is not required for dendritic cell stimulation of the mixed leukocyte reaction. J. Immunol. 2005;175:4265–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4265. This paper reports that DC-SIGN is not required for DC transmission of HIV and stimulation of T cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Macatonia SE, Lau R, Patterson S, Pinching AJ, Knight SC. Dendritic cell infection, depletion and dysfunction in HIV-infected individuals. Immunology. 1990;71:38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knight SC, Patterson S, Macatonia SE. Stimulatory and suppressive effects of infection of dendritic cells with HIV-1. Immunol. Lett. 1991;30:213–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(91)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lore K, et al. Accumulation of DC-SIGN+CD40+ dendritic cells with reduced CD80 and CD86 expression in lymphoid tissue during acute HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2002;16:683–92. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fidler SJ, et al. An early antigen-presenting cell defect in HIV-1-infected patients correlates with CD4 dependency in human T-cell clones. Immunology. 1996;89:46–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sapp M, et al. Dendritic cells generated from blood monocytes of HIV-1 patients are not infected and act as competent antigen presenting cells eliciting potent T-cell responses. Immunol. Lett. 1999;66:121–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Granelli-Piperno A, Shimeliovich I, Pack M, Trumpfheller C, Steinman RM. HIV-1 selectively infects a subset of nonmaturing BDCA1-positive dendritic cells in human blood. J. Immunol. 2006;176:991–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Messmer D, et al. Endogenously expressed nef uncouples cytokine and chemokine production from membrane phenotypic maturation in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2002;169:4172–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fanales-Belasio E, et al. Native HIV-1 Tat protein targets monocyte-derived dendritic cells and enhances their maturation, function, and antigen-specific T cell responses. J. Immunol. 2002;168:197–206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quaranta MG, Tritarelli E, Giordani L, Viora M. HIV-1 Nef induces dendritic cell differentiation: a possible mechanism of uninfected CD4(+) T cell activation. Exp. Cell Res. 2002;275:243–54. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Izmailova E, et al. HIV-1 Tat reprograms immature dendritic cells to express chemoattractants for activated T cells and macrophages. Nat. Med. 2003;9:191–7. doi: 10.1038/nm822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andrieu M, et al. Downregulation of major histocompatibility class I on human dendritic cells by HIV Nef impairs antigen presentation to HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2001;17:1365–70. doi: 10.1089/08892220152596623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shinya E, et al. Endogenously expressed HIV-1 nef down-regulates antigen-presenting molecules, not only class I MHC but also CD1a, in immature dendritic cells. Virology. 2004;326:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buseyne F, et al. MHC-I-restricted presentation of HIV-1 virion antigens without viral replication. Nat. Med. 2001;7:344–9. doi: 10.1038/85493. This article describes MHC-class-I-restricted cross-presentation of HIV-1 antigens without viral replication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spira AI, et al. Cellular targets of infection and route of viral dissemination after an intravaginal inoculation of simian immunodeficiency virus into rhesus macaques. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:215–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hu J, Miller CJ, O'Doherty U, Marx PA, Pope M. The dendritic cell-T cell milieu of the lymphoid tissue of the tonsil provides a locale in which SIV can reside and propagate at chronic stages of infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 1999;15:1305–14. doi: 10.1089/088922299310205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu J, Gardner MB, Miller CJ. Simian immunodeficiency virus rapidly penetrates the cervicovaginal mucosa after intravaginal inoculation and infects intraepithelial dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2000;74:6087–95. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6087-6095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hu Q, et al. Blockade of attachment and fusion receptors inhibits HIV-1 infection of human cervical tissue. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1065–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lederman MM, Offord RE, Hartley O. Microbicides and other topical strategies to prevent vaginal transmission of HIV. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:371–82. doi: 10.1038/nri1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Geijtenbeek TB, et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin G, et al. Differential N-linked glycosylation of human immunodeficiency virus and Ebola virus envelope glycoproteins modulates interactions with DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. J. Virol. 2003;77:1337–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1337-1346.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pohlmann S, et al. DC-SIGN interactions with human immunodeficiency virus: virus binding and transfer are dissociable functions. J. Virol. 2001;75:10523–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10523-10526.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu L, Martin TD, Han YC, Breun SK, KewalRamani VN. Trans-dominant cellular inhibition of DC-SIGN-mediated HIV-1 transmission. Retrovirology. 2004;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee B, et al. cis Expression of DC-SIGN allows for more efficient entry of human and simian immunodeficiency viruses via CD4 and a coreceptor. J. Virol. 2001;75:12028–38. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12028-12038.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trumpfheller C, Park CG, Finke J, Steinman RM, Granelli-Piperno A. Cell type-dependent retention and transmission of HIV-1 by DC-SIGN. Int. Immunol. 2003;15:289–98. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nobile C, Moris A, Porrot F, Sol-Foulon N, Schwartz O. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env-mediated fusion by DC-SIGN. J. Virol. 2003;77:5313–23. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5313-5323.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Engering A, Van Vliet SJ, Geijtenbeek TB, Van Kooyk Y. Subset of DC-SIGN(+) dendritic cells in human blood transmits HIV-1 to T lymphocytes. Blood. 2002;100:1780–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gurney KB, et al. Binding and transfer of human immunodeficiency virus by DC-SIGN+ cells in human rectal mucosa. J. Virol. 2005;79:5762–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5762-5773.2005. A study showing that efficient HIV transmission by DC-SIGN-expressing immature DCs in human rectal mucosa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu L, et al. Rhesus macaque dendritic cells efficiently transmit primate lentiviruses independently of DC-SIGN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:1568–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032654399. This paper reports DC-SIGN-independent transmission of primate lentiviruses by rhesus macaque DCs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu L, Martin TD, Vazeux R, Unutmaz D, KewalRamani VN. Functional evaluation of DC-SIGN monoclonal antibodies reveals DC-SIGN interactions with ICAM-3 do not promote human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission. J. Virol. 2002;76:5905–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5905-5914.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baribaud F, Pohlmann S, Leslie G, Mortari F, Doms RW. Quantitative expression and virus transmission analysis of DC-SIGN on monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2002;76:9135–42. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9135-9142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gummuluru S, Rogel M, Stamatatos L, Emerman M. Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to immature dendritic cells can occur independently of DC-SIGN and mannose binding C-type lectin receptors via a cholesterol-dependent pathway. J. Virol. 2003;77:12865–74. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12865-12874.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Soilleux EJ, et al. Constitutive and induced expression of DC-SIGN on dendritic cell and macrophage subpopulations in situ and in vitro. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;71:445–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Krutzik SR, et al. TLR activation triggers the rapid differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2005;11:653–60. doi: 10.1038/nm1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chehimi J, et al. HIV-1 transmission and cytokine-induced expression of DC-SIGN in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2003;74:757–63. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nguyen DG, Hildreth JE. Involvement of macrophage mannose receptor in the binding and transmission of HIV by macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:483–93. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kwon DS, Gregorio G, Bitton N, Hendrickson WA, Littman DR. DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of HIV is required for trans-enhancement of T cell infection. Immunity. 2002;16:135–44. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00259-5. This paper reports that HIV internalization is important for efficient DC-SIGN-mediated viral transmission. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu L, Martin TD, Carrington M, KewalRamani VN. Raji B cells, misidentified as THP-1 cells, stimulate DC-SIGN-mediated HIV transmission. Virology. 2004;318:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.028. This paper shows that DC-SIGN transmission of HIV is cell-type-dependent and suggests that there are features common to B cells and DCs facilitating viral transmission. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Soilleux EJ, et al. Placental expression of DC-SIGN may mediate intrauterine vertical transmission of HIV. J. Pathol. 2001;195:586–92. doi: 10.1002/path.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jameson B, et al. Expression of DC-SIGN by dendritic cells of intestinal and genital mucosae in humans and rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 2002;76:1866–75. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1866-1875.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Engering A, et al. Dynamic populations of dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 grabbing nonintegrin-positive immature dendritic cells and liver/lymph node-specific ICAM-3 grabbing nonintegrin-positive endothelial cells in the outer zones of the paracortex of human lymph nodes. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;164:1587–95. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63717-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Soilleux EJ, Coleman N. Langerhans cells and the cells of Langerhans cell histiocytosis do not express DC-SIGN. Blood. 2001;98:1987–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Weissman D, Li Y, Orenstein JM, Fauci AS. Both a precursor and a mature population of dendritic cells can bind HIV. However, only the mature population that expresses CD80 can pass infection to unstimulated CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 1995;155:4111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cavrois M, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus fusion to dendritic cells declines as cells mature. J. Virol. 2006;80:1992–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1992-1999.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bakri Y, et al. The maturation of dendritic cells results in postintegration inhibition of HIV-1 replication. J. Immunol. 2001;166:3780–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Frank I, et al. Infectious and whole inactivated simian immunodeficiency viruses interact similarly with primate dendritic cells (DCs): differential intracellular fate of virions in mature and immature DCs. J. Virol. 2002;76:2936–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2936-2951.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Arrighi JF, et al. Lentivirus-mediated RNA interference of DC-SIGN expression inhibits human immunodeficiency virus transmission from dendritic cells to T cells. J. Virol. 2004;78:10848–55. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10848-10855.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, et al. Efficient virus transmission from dendritic cells to CD4+ T cells in response to antigen depends on close contact through adhesion molecules. Virology. 1997;239:259–68. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Garcia E, et al. HIV-1 trafficking to the dendritic cell-T-cell infectious synapse uses a pathway of tetraspanin sorting to the immunological synapse. Traffic. 2005;6:488–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bromley SK, et al. The immunological synapse. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:375–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:569–79. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pelchen-Matthews A, Kramer B, Marsh M. Infectious HIV-1 assembles in late endosomes in primary macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:443–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nguyen DG, Booth A, Gould SJ, Hildreth JE. Evidence that HIV budding in primary macrophages occurs through the exosome release pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52347–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sharova N, Swingler C, Sharkey M, Stevenson M. Macrophages archive HIV-1 virions for dissemination in trans. EMBO J. 2005;24:2481–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Moris A, et al. Blood. First Edition. May 4, 2006. Dendritic cells and HIV-specific CD4+ T cells: HIV antigen presentation, T cell activation, viral transfer. Paper, prepublished online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Brenchley JM, et al. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:749–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mehandru S, et al. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:761–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Granelli-Piperno A, Zhong L, Haslett P, Jacobson J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells, infected with vesicular stomatitis virus-pseudotyped HIV-1, present viral antigens to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Immunol. 2000;165:6620–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Triques K, Stevenson M. Characterization of restrictions to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of monocytes. J. Virol. 2004;78:5523–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5523-5527.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chiu YL, et al. Cellular APOBEC3G restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4+ T cells. Nature. 2005;435:108–14. doi: 10.1038/nature03493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Raposo G, et al. Human macrophages accumulate HIV-1 particles in MHC II compartments. Traffic. 2002;3:718–29. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wille-Reece U, et al. HIV Gag protein conjugated to a Toll-like receptor 7/8 agonist improves the magnitude and quality of Th1 and CD8+ T cell responses in nonhuman primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15190–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507484102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mascarell L, et al. Delivery of the HIV-1 Tat protein to dendritic cells by the CyaA vector induces specific Th1 responses and high affinity neutralizing antibodies in non human primates. Vaccine. 2006;24:3490–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Trumpfheller C, et al. Intensified and protective CD4+ T cell immunity in mice with anti-dendritic cell HIV gag fusion antibody vaccine. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:607–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lu W, Arraes LC, Ferreira WT, Andrieu JM. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for chronic HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2004;10:1359–65. doi: 10.1038/nm1147. The first paper reports effective dendritic cell-HIV therapeutic vaccine for chronic AIDS patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kundu SK, et al. A pilot clinical trial of HIV antigen-pulsed allogeneic and autologous dendritic cell therapy in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 1998;14:551–60. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Curtis BM, Scharnowske S, Watson AJ. Sequence and expression of a membrane-associated C-type lectin that exhibits CD4-independent binding of human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein gp120. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:8356–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rappocciolo G, et al. DC-SIGN on B lymphocytes is required for transmission of HIV-1 to T lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e70. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020070. A recent paper reporting the induction of DC-SIGN on activated primary B lymphocytes potentiating HIV transmission to T cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tailleux L, et al. DC-SIGN is the major Mycobacterium tuberculosis receptor on human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:121–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mitchell DA, Fadden AJ, Drickamer K. A novel mechanism of carbohydrate recognition by the C-type lectins DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Subunit organization and binding to multivalent ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:28939–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Feinberg H, Mitchell DA, Drickamer K, Weis WI. Structural basis for selective recognition of oligosaccharides by DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Science. 2001;294:2163–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1066371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Feinberg H, Guo Y, Mitchell DA, Drickamer K, Weis WI. Extended neck regions stabilize tetramers of the receptors DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. J. Biol. Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sol-Foulon N, et al. HIV-1 Nef-induced upregulation of DC-SIGN in dendritic cells promotes lymphocyte clustering and viral spread. Immunity. 2002;16:145–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ganesh L, et al. Infection of specific dendritic cells by CCR5-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promotes cell-mediated transmission of virus resistant to broadly neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 2004;78:11980–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11980-11987.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]