Abstract

One form of juvenile onset autosomal recessive amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS2) has been linked to the dysfunction of the ALS2 gene. The ALS2 gene is expressed in lymphoblasts, however, whether ALS2-deficiency affects periphery blood is unclear. Here we report that ALS2 knockout (ALS2−/−) mice developed peripheral lymphopenia but had higher proportions of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in which the stem cell factor-induced cell proliferation was up-regulated. Our findings reveal a novel function of the ALS2 gene in the lymphopoiesis and hematopoiesis, suggesting that the immune system is involved in the pathogenesis of ALS2.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), ALS2, ALS2 knockout mice, lymphopenia, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, cytokine-stimulated proliferation, stroma

1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is the most common motor neuron disease caused by a selective loss of lower and upper motor neurons in the central nerve system (CNS) (Cleveland and Rothstein, 2001). Recently, mutations in a second ALS-related gene (ALS2) were identified, which cause a rare recessive form of juvenile onset ALS (ALS2) (Hadano et al., 2001;Yang et al., 2001) adding onto the previously defined mutations in the copper/zinc superoxide dismutase 1-(SOD1) (Rosen, 1993). The fact that both SOD1 and ALS2 gene are expressed in a broad range of cell types in different tissues of various animal species led us to believe that mutations in these genes may affect systems other than the CNS. One of the systems warrants further investigation is the lymphohematopoietic system. A direct link between ALS and the lymphohematopoietic system comes from the clinical observation that ALS patients had marked lymphopenia with reductions in CD2+ and CD8+ T cells in comparison to age-matched normal controls (Provinciali et al., 1988). The “ALS”-like disorder seen in patients with HIV infection further suggests that reduced immunity with viral infection might be a key element in the pathogenesis of ALS (Verma and Berger, 2006;Sinha et al., 2004). Most recently, a significant decrease of white blood cells was observed in the SOD1G93A transgenic mouse model of ALS, further supporting the role of immunodeficiency in ALS (Kuzmenok et al., 2006). However, whether ALS2-deficiency affects immune system is not clear.

Previously, we along with others have developed a mouse model of ALS2 by generation of ALS2 knockout (ALS2−/−) mice (Cai et al., 2005;Hadano et al., 2006;Devon et al., 2006;Yamanaka et al., 2006). The resultant ALS2−/− mice exhibit deficits in motor activities but lack obvious motor neuron degeneration. Since the ALS2 gene was also expressed in lymphoblasts from normal individuals (Yamanaka et al., 2003), the hematopoietic system could be affected in ALS2−/− mice. Here we examined lymphohematopoietic phenotypes in ALS2−/− mice. In comparison to wild-type (ALS2+/+) littermate controls, ALS2−/− mice showed mild lymphopenia with enlarged Lin−Kit+Sca1+CD34− HSC and Lin−Kit+Sca1+CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cell pools. When cultured in vitro with stem cell factor (SCF), sorted Lin−CD117+CD34+ and Lin−CD117+CD34− cells from ALS2−/− bone marrow (BM) expanded more than the same cells from wild type controls. BM cells from ALS2−/− mice also had reduced ability to form stromal feeder layer to support the growth of cobblestone colonies. Thus, Our findings reveal a novel function of the ALS2 gene in the lymphopoiesis and hematopoiesis, suggesting that the immune system is involved in the pathogenesis of ALS2.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and antibodies

ALS2−/− mice were generated as previously described (Cai et al., 2005). All mice are on a mixed (129/SvJ × C57BL/6J) background. The mice were housed in a 12-hour light/dark cycle and fed regular diet ad libitum. The experimental protocols utilized in this paper are in accordance to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We used six pairs of young (3 months old) and four pairs of old (14 ± 1.89 months old, Mean ± SE) ALS2−/− and ALS2+/+ littermate control mice in the current study. Monoclonal antibodies for murine CD3 (clone 145-2C11), CD4 (clone GK 1.5), CD8 (clone 53-6.72), CD11b (clone M1/70), CD19 (clone ID3), CD34 (clone RAM34), CD45R (B220, clone RA3-6B2), CD117 (CD117, clone 2B8), erythroid cells (clone Ter119), granulocytes (Gr1/Ly6-G, clone RB6-8C5), and stem cell antigen 1 (Sca1, clone E13-161) were all purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Antibodies were conjugated with fluorescein isothyocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), phycoerythrin-Cyane 5 (PE-Cy5), or allophycocyanin (APC).

2.2. ALS2 expression in BM cells

BM cells were flushed from tibiae and femurs of ALS2+/+ mice into Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM, ATCC, Manasses, VA). Erythrocytes were lysed by incubating with Gey's solution (130.68 mM NH4Cl, 4.96 mM KCl, 0.82 mM Na2HPO4, 0.16 mM KH2PO4, 5.55 mM dextrose, 1.03 mM MgCl2, 0.28 mM MgSO4, 1.53 mM CaCl2 and 13.39 mM NaHCO3) for 10 minutes on ice. Residual cells were stained with a CD3-FITC + CD11b-Cychrome + CD45R-APC antibody cocktail and were sorted into CD3+, CD11b+, and CD45R+ fractions. Cell sorting was carried out using a BD FACS Vantage SE with DiVa Cell Sorter (Becton Dickson, San Jose, CA), which was equipped with an Innova Argon 90 laser operating at 0.150 watt of visible line and a 0.50 watt Helium Neon laser operating at ∼633 nm. Sorting was carried out at 35Psi and 71.1 kilohertz with less than 2.0% CV for each optical detector.

Total RNA was isolated from each sorted cell fraction using the RNeasy Micro and QIAshredder kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum Taq High Fidelity Kit (Invitrogen) was used to amplify ALS2 mRNA covering exons 31 to 33 of ALS2 gene with the forward primer mALS2-Ex31F: AGGATGCTTGCTTTGCATCT and the reverse primer mALS2-Ex33R: GCCTTCAAGGTGGTGAACAT. β-actin primers were used as controls. RT-PCR was performed at 1 cycle of 50°C for 30 min, 1 cycle of 94°C for 2 min, 20-21 cycles of amplification at 94°C for 30”, 60-62°C for 30” and 72°C for 45”, plus a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The RT-PCR products for ALS2 were used as templates for a second round amplification using a pair of nested PCR primers of ALS2 exons 31 to 33. The final PCR products were separated by electrophoresis through 2% agarose containing ethidium bromide.

2.3. Cell analysis and flow cytometry

Peripheral blood (PB) was obtained through retro-orbital sinus bleeding. One micro-tube of blood (∼75 μl) was obtained from each animal for complete blood count (CBC) analyses using a Hemavet 950 analyzer (Drew Scientific Inc., Oxford, CT) whereas two more micro-tubes of blood was collected from each mouse for flow cytometry analyses. BM cells were flushed out from two tibiae and femurs of each animal into 2 mL of IMDM, filtered through a 90-μm nylon mesh (Small Parts Inc., Miami Lakes, FL), and counted by using a Vi-Cell XP Cell Viability Analyzer (Beckman-Coulter Corp, Hialeah, FL). Only viable cells were counted and used in calculations. Total BM cells per mouse were calculated based on the assumption that two tibiae and two femurs contain 25% of all BM cells in the body.

For flow cytometry analyses, blood and BM cells were incubated with Gey's solution twice of 10 minutes each at 4°C to lyse RBCs. Cells were then stained with pre-mixed antibody cocktails, and were analyzed using a BD-LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Each acquisition was stopped when 20,000 or 1,000,000 cells were collected, depending on the type of analysis.

2.4. SCF-stimulated cell proliferation in vitro

To study the effect of ALS2 deletion on hematopoietic cell proliferation, we stained BM cells from ALS2−/− and wild-type mice with a pre-mixed antibody cocktail containing CD34-PE-Cy5 + Lineage (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD19, Gr1, Ter119)-PE + CD117-APC, and sorted out Lin−CD117+CD34+ and Lin−CD117+CD34− cell fractions using a BD FACS Vantage SE with DiVa Cell Sorter as described earlier. Sorted cells from ALS2−/− and wild-type mice were cultured in 12-well polystyrene flat bottom tissue culture plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY 14831) at 3000 cells/well in 2 mL of Dulbecco's modified essential medium (DMEM, Cellgro Media tech, VA) supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 U/mL streptomycin, 2 μM L-glutamine, 3 ng/mL IL-3, and 5 ng/mL IL-6. Cells were cultured in duplicate or triplicate wells at 37°C with 5% CO2with or without the addition of 25 ng/mL SCF. At the end of the 7-day culture, cells were harvested and counted under a light microscope to calculate cell expansion defined as the ratio between the number of cells recovered and the number of cells used to initiate culture.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data collected from different assays were statistically analyzed using the JMP statistical discovery software with least square models (SAS et al., 1998). Results shown in Tables or Figures were means and standard errors, while statistical significance was declared at P<0.05 and P<0.01 levels respectively.

3. Results

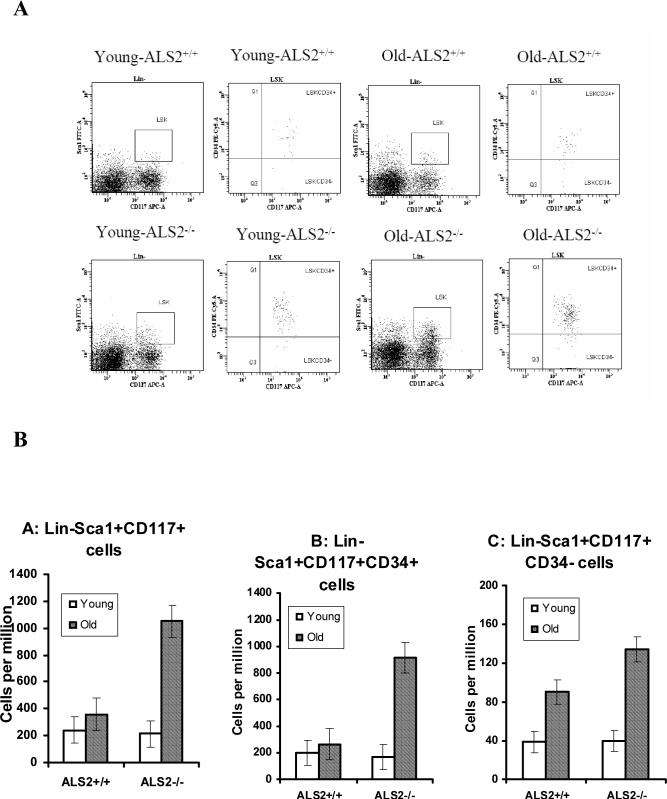

3.1. ALS2 is widely expressed in BM cells of all hematopoietic lineages

A previous experiment reports that ALS2 is expressed in the lymphoblasts (Yamanaka et al., 2003). However, whether the ALS2 gene is expressed in BM cells of all hematopoietic lineages is unclear. In our initial experiment, we examined the expression of ALS2 mRNA in sorted CD3+ T cells, CD45R+ B cells, and CD11b+ myeloid cells as well as in unfractionated whole BM cells. Data from RT-PCR analyses indicated that ALS2 gene is ubiquitously expressed in T and B cells of the lymphoid cell lineage as well as in cells of the myeloid lineage, despite that the signal was slightly weaker in myeloid cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Total RNA was extracted from sorted CD45R+(lane 1), CD11b+ (lane 2), CD3+ (lane 3) and unfractionated whole BM cells (WBM, lane 4) from young ALS2+/+ mice and subjected to reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses of ALS2 (upper panel) and β-actin gene expression (lower panel).

3.2. Circulating leukocyte number is reduced in ALS2−/− mice

To investigate whether the blood cells are affected by loss of the ALS2 gene, we measured the peripheral blood cellular composition in ALS2+/+ and ALS2−/− mice at 3 and 14 months of age. Circulating white blood cells (WBCs) reduced significantly (P<0.01) with age in ALS2+/+ and ALS2−/− mice, whereas ALS2−/− mice had significantly fewer (P<0.05) WBCs than ALS2+/+ littermates at both young and older ages (Table 1). The reduction in WBC concentration in ALS2−/− mice was caused by a decline the concentration of lymphocytes in these mice compared to the wild-type controls (P<0.08). In contrast, blood concentrations of neutrophils, monocytes, basophils and eosinophils showed no obvious difference between ALS2+/+ and ALS2−/− mice (Table 1). In addition, the red blood cells (RBC) and platelet concentrations did not change in ALS2−/− mice either.

Table 1.

Complete blood count

| Young |

Old |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | ALS2+/+ | ALS2−/− | ALS2+/+ | ALS2−/− | Stat |

| WBC (106/mL) | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 6.1 ± 1.1 | 4.8 ± 1.0 | A, g |

| Lymphocytes (106/mL) | 6.8 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | A |

| Neutrophils (106/mL) | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | NS |

| Monocytes (106/mL) | 0.225±0.085 | 0.270±0.085 | 0.357±0.120 | 0.315±0.104 | NS |

| Basophiles (106/mL) | 0.030±0.017 | 0.015±0.020 | 0.030±0.024 | 0.063±0.020 | NS |

| Eosinophiles (106/mL) | 0.007±0.003 | 0.002±0.003 | 0.010±0.004 | 0.008±0.003 | NS |

| RBC (109/mL) | 9.7 ± 0.4 | 9.6 ± 0.4 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 8.6 ± 0.5 | NS |

| Platelets (106/mL) | 834 ± 84 | 711 ± 84 | 1041 ± 119 | 919 ± 103 | NS |

Complete blood counts were performed for young (3 months) and older (14 months) ALS2 wild type (ALS2+/+) and ALS2 knockout (ALS2−/−) mice. Data shown are least square means ± standard errors of 6 mice from each of the two young groups and of 4 mice from each of the two old groups after variance analyses. Statistics: A: significant age effect (P<0.01); g: significant genotype effect (P<0.05); NS: no significance.

In partitioning peripheral blood leukocytes into different subsets, we found that proportions of CD4+, CD8+, and CD11b+ were not different between ALS2+/+ and ALS2−/− mice, despite that both CD4+ (P<0.01) and CD8+ (P<0.05) cell proportions were significantly reduced with age (Table 2). Older ALS2−/− mice had lower proportions of CD45R+ B cells and higher proportions of Ter119+ erythrocytes than ALS2+/+ mice, but these differences did not reach the level of significance (Table 2). In comparison to ALS2+/+ controls, ALS2−/− mice seemed to have slightly higher proportion of CD4 cells but lower proportions of CD8 T cells and CD45R B cells in both age groups (Table 2), although these differences were not statistically significant. Thus, reduction in lymphocytes in ALS2−/− mice might associate with further reduction of cytotoxic T cells (CD8) and the antibody-producing B cells (CD45R).

Table 2.

Cellular composition in peripheral blood

| Genotype | CD4% | CD8% | CD11b% | CD45R% | Ter119% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young ALS2+/+ | 13.6 ± 2.5 | 10.1 ± 1.8 | 23.6 ± 5.9 | 34.4 ± 4.7 | 13.1 ± 7.5 |

| Young ALS2−/− | 15.0 ± 2.5 | 9.9 ± 1.8 | 23.4 ± 5.9 | 32.7 ± 4.7 | 13.8 ± 7.5 |

| Old ALS2+/+ | 5.1 ± 3.5 | 4.6 ± 2.5 | 20.2 ± 7.2 | 24.5 ± 5.8 | 22.0 ± 9.2 |

| Old ALS2−/− | 5.4 ± 3.0 | 3.9 ± 2.2 | 30.8 ± 7.2 | 19.2 ± 5.8 | 35.7 ± 9.2 |

| Statistics | A | a | NS | a | NS |

Peripheral blood from young (3 months) and older (14 months) ALS2 wild type (ALS2+/+) and ALS2 knockout (ALS2−/−) mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are least square means ± standard errors of 6 mice from each of the two young groups and 4 mice from each of the two old groups after variance analyses. Statistic significance: A: significant age effect (P<0.01); a: significant age effect (P<0.05); NS: no significance.

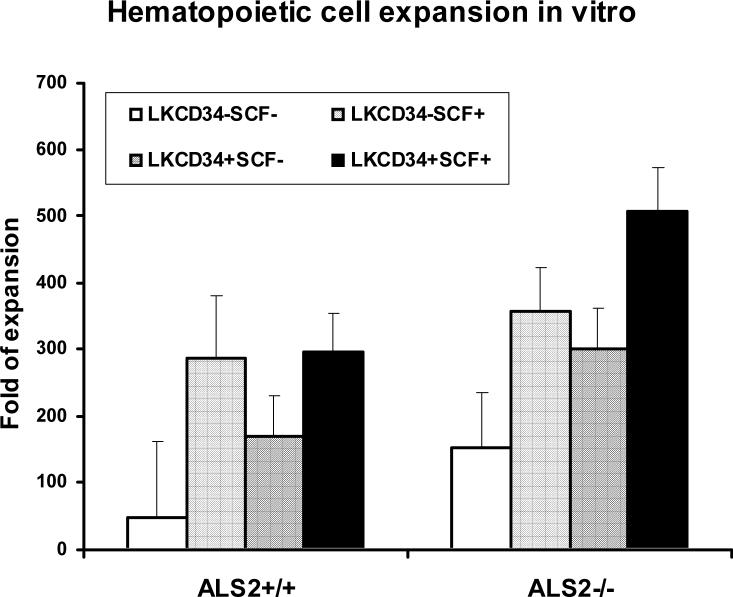

3.3. Age-associated upregulation in hematopoietic cell proliferation in ALS2−/− mice

The reduced number of mature leukocytes in ALS2−/− mice could be contributed by a reduced number of hematopoietic precursors in the BM. To test this hypothesis, we stained BM cells using previously established marker combinations for mature and immature progenitor cells. We found that the proportion of CD4+ cells was actually higher (P<0.01) in older ALS2−/− than in age-matched ALS2+/+ mice (Table 3). Proportions of CD8+, CD11b+, and CD45R+ cells were all insignificantly lower in ALS2−/− than in ALS2+/+ mice, consistent with observations from the blood (Table 2), whereas proportion of Ter119+ erythrocytes was significantly (P<0.05) higher in ALS2−/− mice than in ALS2+/+ controls (Table 3). At young age, ALS2−/− mice had similar proportions of Lin−Sca1+CD117+, Lin−Sca1+CD117+CD34+, and Lin−Sca1+CD117+CD34- cells in the BM as ALS2+/+ mice, whereas at old age ALS2−/− mice had significantly higher (P<0.01) proportions of all these cell populations than those in ALS2+/+ mice (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Cellular composition in BM

| Genotype | CD4% | CD8% | CD11b% | CD45R% | Ter119% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young ALS2+/+ | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 46.9 ± 4.2 | 19.7 ± 4.6 | 20.1 ± 3.2 |

| Young ALS2−/− | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 37.4 ± 4.6 | 18.9 ± 5.1 | 29.4 ± 3.5 |

| Old ALS2+/+ | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 41.1 ± 5.1 | 24.0 ± 5.7 | 25.6 ± 3.9 |

| Old ALS2−/− | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 37.7 ± 5.1 | 20.2 ± 5.7 | 36.6 ± 3.9 |

| Statistics | A, g, A*G | NS | NS | NS | g |

BM cells from young (3 months) and old (14 months) ALS2 wild type (ALS2+/+) and ALS2 knockout (ALS2−/−) mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are least square means ± standard errors of 6 mice from each of the two young groups and 4 mice from each of the two old groups after variance analyses. Statistic significance: A: significant age effect (P<0.01); g: significant genotype effect (P<0.05); A*G: significant age*genotype interaction (P<0.05); NS: no significance.

Fig. 2.

BM cells extracted from young (3 months) and old (14 months) mice were stained with Sca1-FITC + Lin (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD45R, Gr1, Ter119)-PE + CD34-PE-Cy5 + CD117-APC and analyzed by a LSR II flow cytometry. Lin- cells were gated first to display the Sca1CD117 double positive cell population as the LSK cells, which were then gated to display CD34 expression. Proportions of Lin−Sca1+CD117+ and Lin−Sca1+CD117+CD34+ cells increased significantly with age in ALS2−/− but not in ALS2+/+ mice while proportion of Lin−Sca1+CD117+CD34− cells increased with age in both ALS2−/− and ALS2+/+ mice. Data shown as representative dot plots (A) as well as least square means with standard error bars from 4 mice analyzed for each genotype/age group (B).

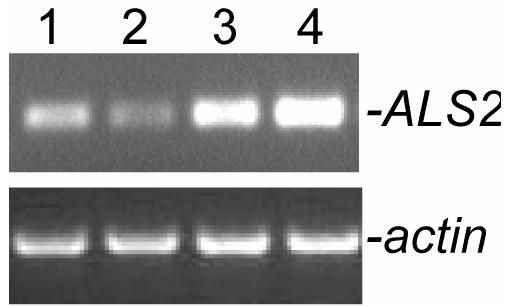

The higher proportions of BM hematopopietic progenitor and stem cells in older ALS2−/− mice suggested that the deletion of ALS2 gene might cause cells to be more responsive to cytokine stimulation-induced cell proliferation. To test this hypothesis, we sorted Lin−CD117+CD34+ and Lin−CD117+CD34− cells from the BM of ALS2−/− and ALS2+/+ mice, and cultured them in vitro for 7 days in the presence of IL-3 and IL-6 with and without 25 ng/mL SCF. We found that the Lin−CD117+CD34+ cells from ALS2−/− mice expanded significantly more than the cells from ALS2+/+ mice (ALS2−/−: 507 ± 66 folds vs. ALS2+/+: 297 ± 58 folds; p < 0.05; Fig. 3). Moreover, the Lin−CD117+CD34− cells from ALS2−/− mice also expanded more (357 ± 66 folds) than the same cells from ALS2+/+ mice (286 ± 93 folds), although this difference was not statistically significant. Taken together, both Lin−CD117+CD34+ and Lin−CD117+CD34− cells from ALS2−/− mice were more responsive to SCF stimulation than the same cells from ALS2+/+ controls. This response, along with the observed peripheral lymphocytopenia, suggest that ALS2 is involved in the regulation of hematopoietic lineage commitment toward T and B cells. Deficiency of ALS2 gene product causes deficiency in lymphocyte commitment which, as an compensatory effect, causes up regulation in the proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

Fig. 3.

Sorted Lin−CD117+CD34+ and Lin−CD117+CD34− BM cells from young ALS2+/+ and ALS2−/− mice were cultured in DMEM in 12-well polystyrene tissue culture plates at 3000 cells/well in the presence of 3 ng/mL IL-3 and 5 ng/mL IL-6 with or without 25 ng/mL SCF. Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2for 7 days. Harvested cells were counted under a light microscope to calculate fold of cell expansion defined as the ratio between the number of cells recovered and the number of cells used to initiate culture. Data presented as means with standard error bars from duplicate or triplicate culture wells for each cell type.

4. Discussion

In this report, we showed that loss of ALS2 gene product resulted in peripheral lymphopenia with reduced proportions of CD8 T cells and CD45R B cells. Proportions of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells were much higher in ALS2-deficient mice, probably because these cells are more sensitive to cytokine-stimulated cell proliferation. Our observations, along with these previous reports (Provinciali et al., 1988; Kuzmenok et al., 2006), suggest a causal link between ALS and lymphopenia.

It will be interesting to know how the ALS2 gene is involved in lymphohematopoiesis and immune function. Based on sequence homology, alsin encoded by the full-length ALS2 gene contains three putative guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor (GEF) like domains: an amino-terminal regulator of chromatin condensation (RCC1) like domain (RLD), a middle Dbl homology (DH)/pleckstrin homology (PH) like domain, and a carboxyl-terminal vacuolar protein sorting 9 (VPS9) like domain, which are homologous to GEFs of Ran, Rho, and Rab GTPase, respectively (Hadano et al., 2001;Yang et al., 2001). Previous studies have shown that the VPS9 domain of alsin in conjunction with its upstream membrane occupation and recognition nexus motifs can specifically activate the Rab5 subfamily GTPases (Otomo et al., 2003;Topp et al., 2004), and the DH/PH domain of alsin is believed to facilitate the activation of members of Rho GTPases (Topp et al., 2004). The role of Rho GTPases in the regulation of hematopoiesis has been well studied in the past. Both Rac1 and Rac2, the hematopoietic-specific Rho family GTPases, play important roles in neutrophil function and host defense (Roberts et al., 1999), phagocyte immunodeficiency (Williams et al., 2000), and hematopoietic cell migration, localization and interaction with microenvironment (Jansen et al., 2005;Cancelas et al., 2005;Gottig et al., 2006). Moreover, Cdc42GAP-deficient mice are anemic with significant declines in BM cells and the numbers of erythroid blast-forming unit (BFU-E) and colony-forming unit (CFU-E) (Wang et al., 2006). Cdc42gap is a negative regulator of Rho family GTPase, Cdc42. We speculate that deficiency in alsin may alter the activities of Rho family GTPases in BM stem and progenitor cells and therefore affects lymphohematopoiesis. However, the mechanism of alsin in lymphohematopoiesis remains to be defined.

Similar to ALS2−/− mice, Trp53 and IL-2-deficient mice also have higher numbers of Lin−Sca1+CD117+CD34− hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the BM (Chen et al., 2002;TeKippe et al., 2003). Interestingly, Trp53−/− and IL-2−/− mice display significantly different HSC function. When tested in competitive repopulation experiments in vivo, Trp53−/− mice expressed very high HSC engraftment activity while IL-2−/− mice expressed very low HSC engraftment (Chen et al., 2002; TeKippe et al., 2003). It will be nice to examine the HSC engraftment activity in ALS2−/− mice. However, it will be difficult to interpret the engraftment assay using HSCs derived from ALS2−/− mice, since a mixed genetic background of ALS2−/− mice in which too many minor-histocompartibility antigen disparities will dramatically interfere with the outcome of HSC engraftment. A congenic line of ALS2−/− mice in C57BL6 background is under development to address this issue.

In summary, although the mechanism of abnormal lymphohematopoiesis and stromal function in ALS2−/− mice remains to be addressed, we are the first to reveal a novel function of alsin in the development of blood cells, suggesting that the immune system is involved in the pathogenesis of ALS2.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Cai H, Lin X, Xie C, Laird FM, Lai C, Wen H, Chiang HC, Shim H, Farah MH, Hoke A, Price DL, Wong PC. Loss of ALS2 function is insufficient to trigger motor neuron degeneration in knock-out mice but predisposes neurons to oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2005a;25:7567–7574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1645-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancelas JA, Lee AW, Prabhakar R, Stringer KF, Zheng Y, Williams DA. Rac GTPases differentially integrate signals regulating hematopoietic stem cell localization. Nat Med. 2005;11:886–891. doi: 10.1038/nm1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Astle CM, Harrison DE. Hematopoietic stem cell functional failure in interleukin-2-deficient mice. J Hematotherapy Stem Cell Res. 2002;11:905–912. doi: 10.1089/152581602321080565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Brandt JS, Ellison FM, Calado RT, Young NS. Defective stromal cell function in a mouse model of infusion-induced bone marrow failure. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland DW, Rothstein JD. From Charcot to Lou Gehrig: deciphering selective motor neuron death in ALS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:806–819. doi: 10.1038/35097565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devon RS, Orban PC, Gerrow K, Barbieri MA, Schwab C, Cao LP, Helm JR, Bissada N, Cruz-Aguado R, Davidson TL, Witmer J, Metzler M, Lam CK, Tetzlaff W, Simpson EM, McCaffery JM, El Husseini AE, Leavitt BR, Hayden MR. Als2-deficient mice exhibit disturbances in endosome trafficking associated with motor behavioral abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9595–9600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510197103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottig S, Mobest D, Ruster B, Grace B, Winter S, Seifried E, Gille J, Wieland T, Henschler R. Role of the monomeric GTPase Rho in hematopoietic progenitor cell migration and transplantation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:180–189. doi: 10.1002/eji.200525607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadano S, Benn SC, Kakuta S, Otomo A, Sudo K, Kunita R, Suzuki-Utsunomiya K, Mizumura H, Shefner JM, Cox GA, Iwakura Y, Brown RH, Jr., Ikeda JE. Mice deficient in the Rab5 guanine nucleotide exchange factor ALS2/alsin exhibit age-dependent neurological deficits and altered endosome trafficking. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:233–250. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadano S, Hand CK, Osuga H, Yanagisawa Y, Otomo A, Devon RS, Miyamoto N, Showguchi-Miyata J, Okada Y, Singaraja R, Figlewicz DA, Kwiatkowski T, Hosler BA, Sagie T, Skaug J, Nasir J, Brown RHJ, Scherer SW, Rouleau GA, Hayden MR, Ikeda JE. A gene encoding a putative GTPase regulator is mutated in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 2. Nat Genet. 2001;29:166–173. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen M, Yang FC, Cancelas JA, Bailey JR, Williams DA. Rac2-deficient hematopoietic stem cells show defective interaction with the hematopoietic microenvironment and long-term engraftment failure. Stem Cells. 2005;23:335–346. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmenok OI, Sanberg PR, Desjarlais TG, Bennett SP, Garbuzova-Davis SN. Lymphopenia and spontaneous autorosette formation in SOD1 mouse model of ALS. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;172:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otomo A, Hadano S, Okada T, Mizumura H, Kunita R, Nishijima H, Showguchi-Miyata J, Yanagisawa Y, Kohiki E, Suga E, Yasuda M, Osuga H, Nishimoto T, Narumiya S, Ikeda JE. ALS2, a novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the small GTPase Rab5, is implicated in endosomal dynamics. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1671–1687. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provinciali L, Laurenzi MA, Vesprini L, Giovagnoli AR, Bartocci C, Montroni M, Bagnarelli P, Clementi M, Varaldo PE. Immunity assessment in the early stages of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a study of virus antibodies and lymphocyte subsets. Acta Neurol Scand. 1988;78:449–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1988.tb03686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AW, Kim C, Zhen L, Lowe JB, Kapur R, Petryniak B, Spaetti A, Pollock JD, Borneo JB, Bradford GB, Atkinson SJ, Dinauer MC, Williams DA. Deficiency of the hematopoietic cell-specific Rho family GTPase Rac2 is characterized by abnormalities in neutrophil function and host defense. Immunity. 1999;10:183–196. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DR. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;364:362. doi: 10.1038/364362c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. JMP Statistics and Graphics Guide, Version 3. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Mathews T, Arunodaya GR, Siddappa NB, Ranga U, Desai A, Ravi V, Taly AB. HIV-1 clade-C-associated “ALS”-like disorder: first report from India. J Neurol Sci. 2004;224:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TeKippe M, Harrison DE, Chen J. Expansion of hematopoietic stem cell phenotype and activity in Trp53-null mice. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Italiano JEJ, Barral DC, Mules EH, Novak EK, Swank RT, Seabra MC, Shivdasani RA. A role for Rab27b in NF-E2-dependent pathways of platelet formation. Blood. 2003;102:3970–3979. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp JD, Gray NW, Gerard RD, Horazdovsky BF. Alsin is a Rab5 and Rac1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem. 2004a;279:24612–24623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A, Berger JR. ALS syndrome in patients with HIV-1 infection. J Neurol Sci. 2006;240:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yang L, Filippi MD, Williams DA, Zheng Y. Genetic deletion of Cdc42GAP reveals a role of Cdc42 in erythropoiesis and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell survival, adhesion, and engraftment. Blood. 2006;107:98–105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA, Tao W, Yang F, Kim C, Gu Y, Mansfield P, Levine JE, Petryniak B, Derrow CW, Harris C, Jia B, Zheng Y, Ambrusom DR, Lowe JB, Atkinson SJ, Dinauer MC, Boxer L. Dominant negative mutation of the hematopoietic-specific Rho GTPase, Rac2, is associated with a human phagocyte immunodeficiency. Blood. 2000;96:1646–1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka K, Miller TM, McAlonis-Downes M, Chun SJ, Cleveland DW. Progressive spinal axonal degeneration and slowness in ALS2-deficient mice. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:95–104. doi: 10.1002/ana.20888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka K, Vande Velde C, Eymard-Pierre E, Bertini E, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Cleveland DW. Unstable mutants in the peripheral endosomal membrane component ALS2 cause early-onset motor neuron disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003a;100:16041–16046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2635267100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Hentati A, Deng HX, Dabbagh O, Sasaki T, Hirano M, Hung WY, Ouahchi K, Yan J, Azim AC, Cole N, Gascon G, Yagmour A, Ben Hamida M, Pericak-Vance M, Hentati F, Siddique T. The gene encoding alsin, a protein with three guanine-nucleotide exchange factor domains, is mutated in a form of recessive amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2001a;29:160–165. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]