Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between genotype and phenotype in idiopathic generalized epilepsies (IGEs) using a novel approach that focuses on seizure type rather than syndrome.

Methods

The authors evaluated whether the genetic effects on myoclonic seizures differ from the genetic effects on absence seizures. For this purpose, they studied 34 families containing 2 or more members with IGEs and assessed whether the number of families concordant for seizure type exceeded that expected by chance. The authors performed a similar analysis to examine the genetic contributions to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE), and childhood absence epilepsy (CAE).

Results

The observed number of families concordant for seizure type (myoclonic, absence, or both) was greater than expected (20 vs 7.51; p < 0.0001). The observed number of families concordant for syndrome was greater than expected when JME was compared with absence epilepsies (JAE+CAE) (17 vs 11.9; p < 0.012) but not when JAE was compared with CAE (8 vs 6.82; p = 0.516).

Conclusions

These results provide evidence for distinct genetic effects on absence and myoclonic seizures, suggesting that examining the two seizure types separately would be useful in linkage studies of idiopathic generalized epilepsies. The approach presented here can also be used to discover other clinical features that could direct division of epilepsies into groups likely to share susceptibility genes.

Despite progress in identifying the monogenic causes of some relatively rare forms of epilepsy, most epilepsy remains unexplained by genes discovered so far, and the relationship between genes and syndromes or seizure types is not clear. This is particularly true for the complex epilepsies, which have multiple genetic (and perhaps nongenetic) influences.

Do genes dictate the specific clinical features of epilepsy rather than simply raising risk for epilepsy overall? If there are such phenotype-specific genes, then what clinical features do they dictate? Answering these questions could elucidate the function of epilepsy genes before gene discovery through molecular studies and guide rational subdivision of epilepsy syndromes for genetic analysis.

The idiopathic generalized epilepsies (IGEs) have posed a particularly difficult problem. Gene discoveries reported to date in the IGEs appear to explain only a small subset of the families and persons with IGEs, and problems with phenotype definition complicate studies.1–4 Some patients may be difficult to diagnose confidently because of atypical or overlapping features, and some families may be difficult to classify when different IGEs coexist within them.

Here we describe a novel approach to the investigation of genetic contributions to epilepsy, focusing on seizure type rather than syndrome and concentrating on myoclonic and absence seizures in particular. We examine the clustering of these seizure types in families to test the hypothesis that some of the genetic influences on them are distinct, i.e., they affect risk for one seizure type but have no effect (or a smaller effect) on risk for the other. Our method and results may clarify phenotype definition for IGE linkage studies and give insight into the mechanisms by which mutations in epilepsy susceptibility genes cause disease.

Methods

Subjects and diagnosis

The families included in this study are drawn from the Epilepsy Family Study of Columbia University (EFSCU), which began in 1985 as a familial aggregation study and evolved into an ongoing genetic linkage study of epilepsy.5 The present study includes 93 persons from 34 families containing multiple members with IGEs. We screened each subject for seizure disorders through either an in-person or telephone interview administered directly or, if the subject was aged <12 years, deceased, or otherwise unavailable, to a close relative. We also administered screening interviews to either the mother or the father of each subject whenever possible. In subjects who screened positive for afebrile seizures, we carried out a complete diagnostic evaluation, including 1) a detailed semistructured diagnostic interview administered in person or on the telephone by a neurologist or physician with specialized training in epilepsy; and whenever possible, 2) review of medical records (frequently containing EEG reports, imaging results, and reports of neurologic examinations); and 3) a study EEG. We administered the diagnostic interview directly to subjects whenever possible. For those who were deceased, aged <12 years, or otherwise unavailable, we interviewed the relative deemed to be the best living informant regarding the subject’s seizure history. Whenever the quality of information regarding seizure history was in question or the subject’s own recall was insufficient, we interviewed additional informants to clarify the seizure history.

The diagnostic interview obtained information on seizure semiology through verbatim descriptions and structured questions about signs and symptoms, and on seizure etiology through questions about the history and timing of specific risk factors previously demonstrated for epilepsy.6 We previously found that seizure classifications based on the original version of this interview were reliable (reproducible) and valid compared with the clinical diagnoses of expert physicians.6,7 In the present study, we used an updated version of the interview, revised to improve classification, particularly the distinction of focal and generalized non-convulsive events.

Senior epileptologists (W.A.H., T.A.P.) reviewed all of the data collected from each subject to arrive at a final diagnosis. To ensure that diagnoses were made blindly with respect to those of other family members, we removed identifying information before this review and reviewed subjects from different families in random order. We used findings from the neurologic examination, EEG, and neuroimaging to supplement the clinical descriptions of seizures and possible etiologic factors.

For many subjects, clinical information was sufficiently detailed and clear for unambiguous classification of seizure and syndrome type; for these subjects we used EEG data to supplement and confirm the diagnoses. However, when clinical information was ambiguous, we required generalized epileptiform abnormalities on EEG (such as generalized spike wave [GSW] or polyspike wave) for diagnosis of a primary generalized seizure or syndrome type. When clinical information and EEG data were inconclusive, we classified subjects’ epilepsy type as unknown.

We defined epilepsy as a lifetime history of two or more unprovoked seizures. In probands and relatives with epilepsy, we classified seizures according to the 1981 criteria of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE). We classified subjects with epilepsy as having myoclonic seizures, absence seizures, or both. We excluded persons from the analysis if they were classified as having “possible” myoclonic or absence seizures or if their history of these seizure types was unknown. Primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCs) were not considered in this analysis, although they did occur in some subjects. Subjects with focal and generalized epilepsy were included in the analysis, but subjects with only focal epilepsy or epilepsy of unknown type (generalized vs focal) were excluded entirely. The analysis of concordance was based on the seizure classifications of subjects with idiopathic epilepsy only; subjects with symptomatic epilepsy, isolated unprovoked seizures, or acute symptomatic seizures (including febrile seizures) were not considered. Married-in persons not genetically related to the other family members were also excluded.

We diagnosed IGE syndromes according to the ILAE definitions but with several adaptations to deal with difficult cases.8 Childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) was always diagnosed when age at onset was <8 years, regardless of seizure frequency. When age at onset was between 9 and 11 years, frequency of absence seizures was used to distinguish between CAE and juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE). When age at onset was ≤12 years, JAE was diagnosed. JAE and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) were distinguished by the more frequent defining seizure type (absence vs myoclonus) or, when frequency was equal, with the seizure type of earliest onset. If one defining seizure type (myoclonus vs absence) occurred in isolation and the other always occurred immediately after a GTC, then the independently occurring seizure type defined the syndrome. For subjects for whom information on these factors was not available or age at onset, frequency, and independence of seizure type were equal, the categories JAE/JME (indistinguishable) and CAE/JAE were used.

We also created an additional category of IGE not otherwise specified (IGE NOS). This category comprises subjects with IGE-like syndromes (primary generalized seizures with or without generalized EEG findings) that for one or more reasons do not fit into existing IGE categories. This includes 1) atypical age at onset/ seizure type constellations; 2) only photosensitive myoclonus; 3) onset after age 30 years; 4) unclear age at onset; 5) atypical seizure types; and 6) isolated GTCs with GSW on EEG. Data on diurnal vs nocturnal timing of GTCs were obtained, but there were no subjects with awakening grand mal in the study. The analysis was restricted to subjects with clearly defined syndromes.

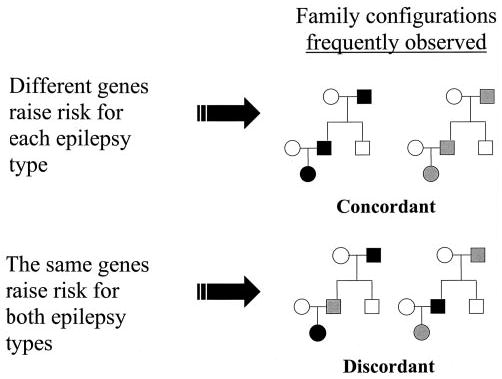

Analysis

The method used to assess clustering of myoclonic and absence seizures in families is the concordance analysis method, which we described in detail previously and used to investigate the genetic effects on generalized vs localization-related epilepsy.9,10 The basic principle underlying the method is that if the genetic effects on epilepsy are type-specific, the number of families concordant for epilepsy type should exceed that expected by chance. Type-specific genetic effects on myoclonic and absence seizures could include genes that affect risk for myoclonic but not absence seizures, genes that affect risk for absence but not myoclonic seizures, or (more generally) genes that affect risk for one seizure type to a greater degree than they affect risk for the other. If none of the genes has such different effects on the two seizure types, then concordance should be consistent with that expected by chance (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Family configurations expected to result from two different underlying genetic models. If different genes raise risk for each type of epilepsy, then families will likely be concordant for epilepsy type. However, if the same genetic influences raise risk for both types, families will likely be discordant for epilepsy type. Gray and black shading represent two different hypothetical epilepsy types.

We define families as concordant if all affected relatives have the same epilepsy subtype of interest; for example, if a family contained four members with IGEs and all four had myoclonic seizures, then the family would be concordant for myoclonic seizures. The number of concordant families in the sample can be easily calculated.

For interpretation, the observed number of concordant families must be compared with the number expected by chance. This is done by a permutation test, in which the expected number is calculated based on two factors: 1) the overall proportion of subjects with each seizure type in all study families; and 2) the number of affected subjects in each family. In addition, we conditioned on proband epilepsy type (when the proband had IGE, myoclonic, or absence seizures) to reflect that the proband’s epilepsy type might have influenced the probability that the family was included in the sample.

Results

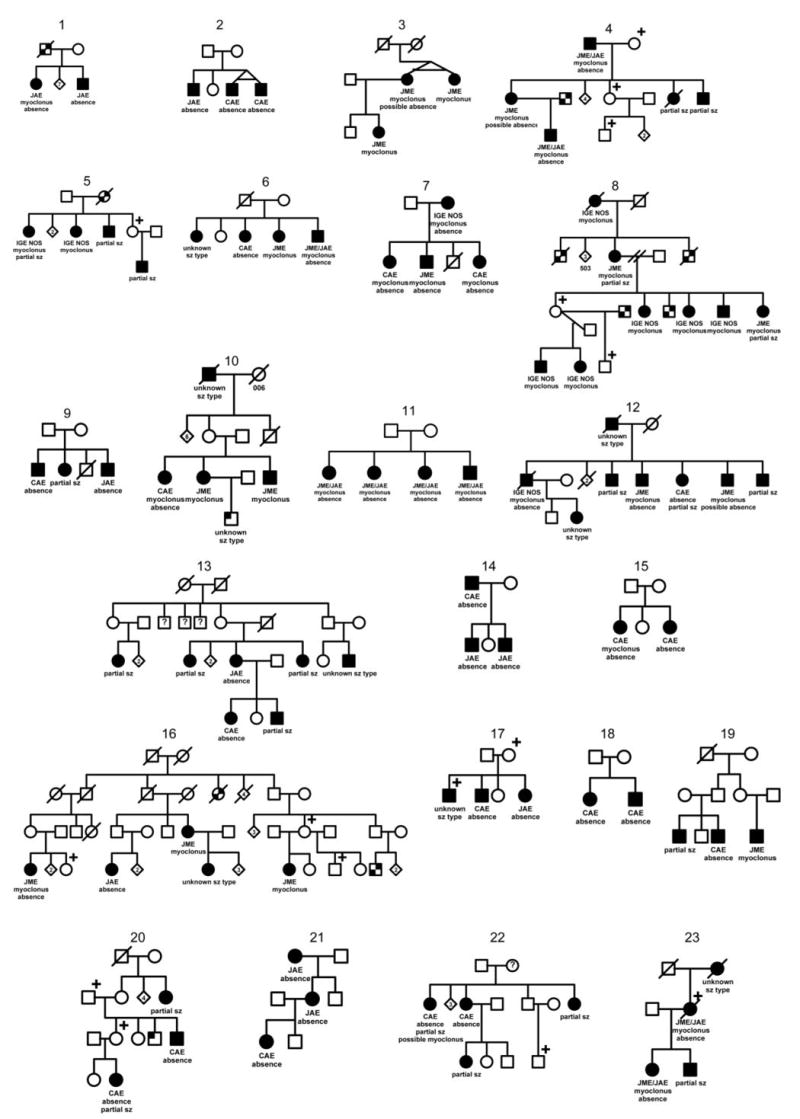

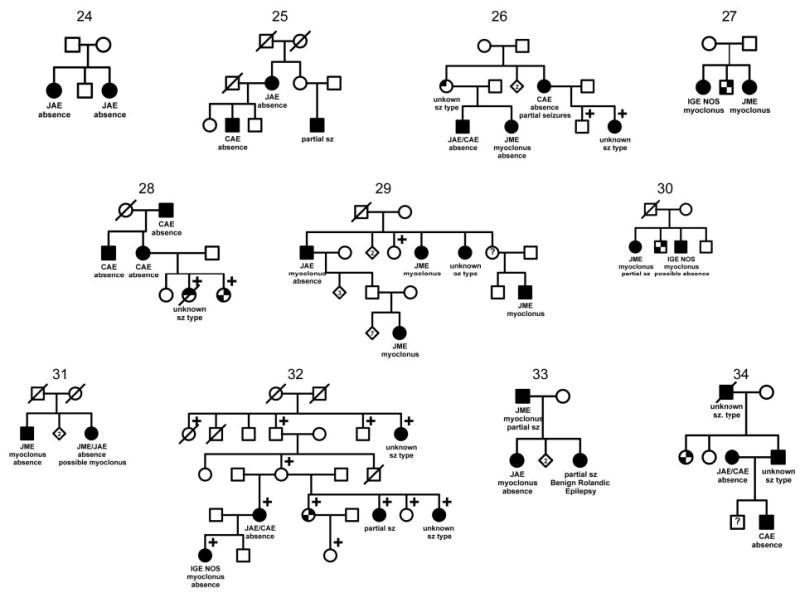

Thirty-four families containing two or more members with IGEs contributed to the seizure-type and IGE syndrome analyses (figure 2). Table 1 shows the distribution of seizure types and syndromes and the distribution of numbers of members with IGEs per family. Of the 93 subjects, 60 (65%) also had primary GTCs. Among the 34 families included, 19 contained 2 members with IGEs (sibling pairs), 9 had 3 affected, 5 had 4 affected, and 1 had 8 affected.

Figure 2.

The 34 families in the Epilepsy Family Study of Columbia University containing ≥2 members with idiopathic generalized epilepsies. ☐, ◯ = unaffected;

,

,

single unprovoked seizure; ☐+, ◯+ = febrile seizure; ⍰ ,

single unprovoked seizure; ☐+, ◯+ = febrile seizure; ⍰ ,

= unknown whether affected; ■, ● = idiopathic epilepsy;

= unknown whether affected; ■, ● = idiopathic epilepsy;

,

,

= symptomatic epilepsy, not febrile;

= symptomatic epilepsy, not febrile;

, ◓ = unknown epilepsy.

, ◓ = unknown epilepsy.

Table 1.

Distribution of IGE syndrome and seizure types in families containing ≥ two individuals with primary generalized epilepsy*

| Syndrome | No. with syndrome, % | No. of individuals with myoclonic seizures only | No. of individuals with absence seizures only | No. of individuals with both seizure types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JME | 23 | 20 | 0 | 3 |

| JAE | 16 | 0 | 13 | 3 |

| Pyknolepsy | 27 | 0 | 23 | 4 |

| JME/JAE | 11 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| JAE/CAE | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| IGE NOS | 14 | 10 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 93 | 30 | 40 | 23 |

For ease of presentation in this table, six individuals with unknown or uncertain myoclonus or absence seizures were classified as not having these types; however, these individuals were excluded from the myoclonus/absence analyses.

IGE = idiopathic generalized epilepsy; JME = juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; JAE = juvenile absence epilepsy; CAE = childhood absence epilepsy; IGE NOS = IGE not otherwise specified.

Eighty-four subjects in 31 families contributed to the myoclonus/absence seizure-type analysis. Three families were excluded because they contained fewer than two members who could be classified clearly based on seizure type—myoclonus only, absence only, or both. Of the remaining 31 families, 20 (65%) were concordant for seizure type; in 2 families all members with IGEs had myoclonic seizures (but not absence seizures); in 12 families all members with IGEs had absence seizures (but not myoclonic seizures); and in 2 families all members with IGEs had myoclonic and absence seizures.

Permutation analysis revealed greater than expected concordance of seizure type among these 31 families, considering myoclonus, absence, and the combination of myoclonus and absence seizures as three different types (table 2). To restrict attention to the independent genetic effects on myoclonus seizures alone and absence seizures alone, we performed an additional analysis excluding subjects with both myoclonic and absence seizures. Concordance for these two seizure types in isolation was again significantly greater than expected by chance (table 2).

Table 2.

Observed vs expected concordance of myoclonic vs absence seizure types and IGE syndrome type

| Number of concordant families

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Z score | p Value (two-tailed) | |

| Seizure type | ||||

| All individuals with myoclonic or absence seizures (31 families) | 20 | 7.51 | 5.65 | <0.0001 |

| Excluding individuals with both myoclonic and absence seizures (23 families) | 19 | 9.80 | 4.14 | <0.0001 |

| Restricted to families with generalized epilepsy (17 families) | 12 | 3.74 | 5.45 | <0.0001 |

| Restricted to families with no unknowns (28 families) | 18 | 7.03 | 5.33 | <0.0001 |

| Syndrome type | ||||

| JME vs JAE vs CAE (25 families) | 10 | 6.17 | 1.87 | 0.062 |

| JME vs (JAE + CAE) (25 families) | 17 | 11.9 | 2.5 | 0.012 |

| JAE vs CAE (15 families)* | 8 | 6.82 | 0.65 | 0.516 |

| Syndrome type (restricted to families with only CAE, JAE, and JME; no partial epilepsy, no unknowns) | ||||

| JME vs JAE vs CAE (19 families) | 8 | 5.10 | 1.57 | 0.116 |

| JME vs (JAE + CAE) (19 families) | 15 | 11.09 | 3.07 | 0.002 |

| JAE vs CAE (14 families) | 7 | 6.07 | 0.53 | 0.596 |

Fewer families were included in these sub-analyses because fewer families had two or more individuals with only JAE or CAE.

IGE = idiopathic generalized epilepsy; JME = juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; JAE = juvenile absence epilepsy; CAE = childhood absence epilepsy; IGE NOS = IGE not otherwise specified.

We also examined the concordance of IGE syndromes (see table 2). We focused our attention on the 61 subjects in 25 families who had clear CAE, JAE, or JME. Because differentiating IGE syndromes can be difficult and vary from one investigator to another, we restricted this analysis to the most typical CAE, JAE, and JME cases. We excluded those with uncertain syndrome diagnoses—those with the overlap syndromes JAE/CAE and JME/JAE, IGE NOS, or unknown seizure types. When the familial clustering of the three syndromes was examined, concordance was not significantly greater than expected, although a trend could be seen toward significance (see table 2). When JME was compared with the two absence epilepsies considered together (CAE + JAE), concordance was significantly greater than expected by chance. When CAE was compared with JAE, however, the number of concordant families did not exceed that expected by chance (table 2).

Because the choice of seizure types included might affect results in unpredictable ways, we performed additional analyses in a sample restricted to families concordant for generalized epilepsy, excluding families in which any member had focal epilepsy. We also repeated the analyses in a subset of families in which no member was classified with an unknown type of epilepsy. Seizure-type and IGE syndrome analyses showed comparable results in these two subsets; concordance of myoclonus vs absence seizures was significantly greater than expected by chance, as was the concordance of JME vs the combined absence epilepsy syndromes, although no significant difference was found between CAE and JAE (see table 2).

Because the number of affected members in a family might affect concordance results, we performed a stratified analysis examining concordance in families with two affected members compared with those with more than two affected members. Seizure-type analyses revealed significantly greater concordance than expected by chance in both strata. Stratified analysis of the IGE syndrome data showed the same results as the unstratified syndrome data with one exception. Concordance was no longer significantly greater than expected by chance for JME vs JAE + CAE in the subset of families with only two affected members. Twelve of 16 families were concordant for seizure type in this group. This was only slightly larger than the expected number, 11 families. All other analyses showed the same results; in the families with more than two affected members, we found evidence for different genetic influences on JME vs JAE + CAE (Z = 2.50; p = 0.0124) and no evidence in either stratum for different genetic influences on JAE vs CAE (Z>2 affecteds = 0.80; p = 0.42 vs Z>2 affecteds = 0.04; p = 0.9681).

Discussion

These results indicate that some genetic influences on myoclonic and absence seizures are distinct, i.e., a gene or genes affect risk for one seizure type without affecting risk for the other to the same degree. We also found evidence for different genetic influences on JME compared with the two absence syndromes, JAE and CAE, but not for different genetic influences on CAE vs JAE. These findings are consistent in supporting the importance of seizure type—rather than, or in addition to, syndrome type—as a defining characteristic in genetic analysis.

We considered whether families containing members with partial or unknown seizure types should be included in this analysis because “mixed” families might harbor genes raising risk for multiple types of epilepsy. Because of this possibility, we restricted some analyses to “pure” IGE families. Other genetic models are also possible. Mixed families may harbor multiple genes, some raising risk for IGEs and others raising risk for the other types of epilepsy. Alternatively, both models may be operating simultaneously, with some genes affecting risk for all types and other genes affecting risk only for individual types. Fortunately, our analytic method is designed to examine a subset of genetic effects on a background of any other effects that may be operating and therefore can examine the genetic effects on myoclonic or absence seizures independent of any other effects on partial epilepsy. Regardless of which genetic model is operating, we can detect different genetic effects on myoclonic and absence seizures. In addition, the results still hold in the subset of families in which all members have epilepsy of known type and in which all members have generalized epilepsy.

Only 2 families were concordant for myoclonic seizures, whereas 12 were concordant for absence seizures. This may appear to indicate type-specific genetic effects on absence seizures but not on myoclonic seizures. However, the absolute number of concordant families is not directly interpretable—statistical significance depends on the difference between expected and observed concordance. Because fewer subjects in our study had myoclonic seizures than absence seizures, fewer families were expected to be concordant for myoclonic seizures or for JME than for absence seizures or an absence syndrome. Also, this method cannot distinguish the relative contributions of each seizure type to the overall significant result. A genotype specific to absence seizures may explain the effect we observe, as may a genotype specific to myoclonic seizures. In any case, these data provide evidence for some difference in the genetic contributions to the two seizure types.

Our results do not indicate that all of the genetic influences on seizure type are separate. Some genes already identified, such as those causing generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus,11,12 are known to raise risk for multiple seizure types. However, the findings do suggest that in future linkage studies of the IGEs, a focus on seizure type in addition to syndrome may be useful.

We previously used the concordance analysis method to examine shared vs distinct genetic influences on generalized and localization-related epilepsy.9 In the future, this method could be applied to examine the genetic effects on other epilepsy subtypes such as lateral vs mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, to electrophysiologic abnormalities such as GSW discharges or the photoparoxysmal response, or to characteristics such as severity or age at onset. Familial clustering of combinations of seizure types, age at onset, and EEG findings could also be examined and may contribute to the development of a biologically driven classification of the epilepsies.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants R01 NS20656 and K23 NS02211.

This information is current as of February 27, 2006

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://www.neurology.org/cgi/content/full/61/11/1576

References

- 1.Wallace RH, Marini C, Petrou S, et al. Mutant GABAA receptor gamma2-subunit in childhood absence epilepsy and febrile seizures. Nat Genet. 2001;28:49–52. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kananura C, Haug K, Sander T, et al. A splice-site mutation in GABRG2 associated with childhood absence epilepsy and febrile convulsions. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1137–1141. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.7.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cossette P, Liu L, Brisebois K, et al. Mutation of GABRA1 in an auto-somal dominant form of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2002;31:184–189. doi: 10.1038/ng885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haug K, Warnstedt M, Alekov AK, et al. Mutations in CLCN2 encoding a voltage-gated chloride channel are associated with idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Nat Genet. 2003;33:527–532. doi: 10.1038/ng1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottman R, Susser M. Data collection strategies in genetic epidemiology: The Epilepsy Family Study of Columbia University. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:721–727. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90049-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ottman R, Hauser WA, Stallone L. Semistructured interview for seizure classification: agreement with physicians’ diagnoses. Epilepsia. 1990;31:110–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb05368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ottman R, Lee JH, Hauser WA, et al. Reliability of seizure classification using a semistructured interview. Neurology. 1993;43:2526–2530. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.12.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1989;30:389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winawer MR, Rabinowitz D, Barker-Cummings C, et al. Evidence for distinct genetic influences on generalized and localization-related epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1176–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.58902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winawer M, Ottman R, Rabinowitz D. Concordance of disease form in kindreds ascertained through affected individuals. Stat Med. 2002;21:1887–1897. doi: 10.1002/sim.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh R, Scheffer IE, Crossland K, Berkovic SF. Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus: a common childhood-onset genetic epilepsy syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:75–81. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199901)45:1<75::aid-art13>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace RH, Wang DW, Singh R, et al. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel beta1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat Genet. 1998;19:366–370. doi: 10.1038/1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]