Abstract

The host specificity of the gram-negative exoparasitic predatory bacterium Micavibrio aeruginosavorus was examined. M. aeruginosavorus preyed on Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as previously reported, as well as Burkholderia cepacia, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and numerous clinical isolates of these species. In a static assay, a reduction in biofilm biomass was observed as early as 3 hours after exposure to M. aeruginosavorus, and an ∼100-fold reduction in biofilm cell viability was detected following a 24-h exposure to the predator. We observed that an initial titer of Micavibrio as low as 10 PFU/well or a time of exposure to the predator as short as 30 min was sufficient to reduce a P. aeruginosa biofilm. The ability of Micavibrio to reduce an existing biofilm was confirmed by scanning electron microscopy. In static and flow cell experiments, M. aeruginosavorus was able to modify the overall P. aeruginosa biofilm structure and markedly decreased the viability of P. aeruginosa. The altered biofilm structure was likely caused by an increase in cell-cell interactions brought about by the presence of the predator or active predation. We also conducted a screen to identify genes important for P. aeruginosa-Micavibrio interaction, but no candidates were isolated among the ∼10,000 mutants tested.

Biofilms are dense aggregations of microbial cells attached to a surface (9, 11). These surface-attached communities are known to have a significant impact on human health when they form on medical and surgical implants (4, 13, 16, 18, 34, 36, 40). A major difficulty in controlling surface-attached bacteria is their enhanced resistance to antimicrobial agents. Biofilms can be 10 to 1,000 times more resistant to antimicrobial agents than their planktonic counterparts (5, 20, 26, 27, 35). The difficulty in controlling biofilms by conventional antibiotic therapy led researchers to examine other methods of biofilm control. Among these alternative techniques is the use of biological control agents, including invertebrates, protozoa, and bacteriophages (10, 14, 15, 19, 21, 28, 29, 33, 38, 43, 45, 46). Predatory prokaryotes from the genus Bdellovibrio have also been shown to have potential for biofilm control (17, 22).

In 1982, while searching for Bdellovibrio samples in wastewater, Lambina and colleagues isolated a new species of exoparasitic bdellovibrio-like bacteria that they called Micavibrio (24). Like Bdellovibrio spp., Micavibrio spp. are characterized by an obligatory parasitic life cycle. Micavibrio organisms are gram negative, small (∼0.5 to 1.5 μm long), rod shaped, and curved and have a single polar flagellum. Phylogenetic analyses have placed Micavibrio spp. within the α subgroup of proteobacteria (12). The Micavibrio cycle of development includes the following stages: motile Micavibrio organisms attach to the cell surfaces of host bacteria, followed by growth of the exoparasite on the surface of the host and, finally, death of the infected cells (2, 25). Unlike Bdellovibrio, Micavibrio spp. were shown to have a high degree of host specificity; for example, Micavibrio aeruginosavorus strain ARL-13 was shown to prey only on Pseudomonas aeruginosa among 55 bacteria of different taxonomic groups that were tested (25).

In this study, we evaluated the ability of M. aeruginosavorus strain ARL-13 to infect pathogenic bacteria grown planktonically and in biofilms. Direct enumeration and microscopy of static and flow-cell-grown biofilms were used to quantify and visualize the extent and nature of damage inflicted on these communities after M. aeruginosavorus treatment. We also describe host cell-cell interactions brought about by predation, indicating that M. aeruginosavorus can promote biofilm formation under some conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

Unless otherwise noted, the strains used in this study were from the laboratory collection. M. aeruginosavorus strain ARL-13 was provided by E. Jurkevitch from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (12). The following bacteria were obtained from Presque Isle cultures (Presque Isle, Erie, PA): Acetobacter aceti (ATCC 23747), Bordetella bronchiseptica (ATCC 10580), Burkholderia cepacia (ATCC 25416), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 19433), Erwinia amylovora (ATCC 7400), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 13883), Mycobacterium smegmatis (ATCC 14468), Salmonella enterica (ATCC 14028), Serratia marcescens strain D (ATCC 27117), Shigella flexneri (ATCC 12022), Staphylococcus simulans (ATCC 11631), and Yersinia enterocolitica (ATCC 23715). Escherichia coli strain ZK2686 was provided by R. Kolter (32, 37), Vibrio cholerae El Tor (3) was provided by R. Taylor, and Pseudomonas syringae BD301D was obtained from M. Klotz. Clinical isolates were provided by J. Schwartzman and R. Kowalski. E. amylovora, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas putida, and P. syringae were routinely grown in LB medium at 30°C. All other bacteria were grown at 37°C.

Cells were enumerated as CFU on LB agar plates. M. aeruginosavorus and Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus were maintained as plaques, as reported previously (41). M. aeruginosavorus populations were quantified as PFU developed on a lawn of prey cells. M. aeruginosavorus lysates were obtained by adding a plug of agar containing an M. aeruginosavorus plaque (∼1 × 106 PFU/ml) to ∼1 × 108 CFU/ml washed prey, followed by a 24-h incubation in DDNB medium. DDNB medium is a 1:50 dilution of nutrient broth with 3 mM MgCl2 · 6H2O and 2 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O. Mixtures of M. aeruginosavorus and host were incubated at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm, and populations of the predator reached a final concentration of ∼1 × 108 PFU/ml. To harvest M. aeruginosavorus, the 24-h lysates were passed three times through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter to remove residual prey and cell debris. These lysates are referred to hereafter as “Micavibrio lysates.” As a control, a Micavibrio lysate was passed three times through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter to remove all of the predator cells, yielding what will be referred to as “sterile lysate.” The Micavibrio lysate was plated on LB agar medium to confirm that no viable host bacterial cells were present in the sample. No predator or host, as judged by CFU and PFU, respectively, could be detected in the sterile lysate (not shown). Dilutions were prepared in saline solution (150 mM NaCl) or 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 2 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O (pH 7.8).

Host range.

The host specificity of M. aeruginosavorus was assessed by the ability of the predator to form a lytic halo on a lawn of prey cells, using a modification of the double-layer plaque assay (42). Host bacteria were grown for 18 h in LB medium, and 100 μl of washed cells was spread on DNB medium solidified with 1.5% agar. Micavibrio lysate (20 μl) was spotted on a lawn of host bacteria. DNB medium is a 1:10 dilution of nutrient broth amended with 3 mM MgCl2 · 6H2O and 2 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O (pH 7.2). Lytic halo assay plates were incubated at 30°C for up to 4 weeks and examined for the formation of a zone of clearing where the lysates were spotted. Each lytic halo assay was performed at least four times in triplicate, with the Micavibrio lysate and the sterile lysate control spotted on each plate.

Bacteria that showed sensitivity to Micavibrio attack in the lytic halo assay were further assessed for predation in a liquid lysate assay. In the liquid lysate assay, sensitivity of the host to Micavibrio was determined by a reduction in host CFU and/or the reduction of turbidity, using a Spectronic 20 spectrophotometer (Spectronic Instruments Inc., Westbury, NY) at 600 nm. Each liquid lysate test was carried out at least three times.

Biofilm and predation assays.

Biofilm formation in 96-well polyvinyl chloride microtiter dishes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was measured by staining with 0.1% crystal violet (CV) in water as described previously (22, 30, 31), with the following modification. Microtiter wells were inoculated (100 μl per well) with an 18-h LB-grown host culture diluted 1:50 in the following media: for P. aeruginosa PA14 biofilms, diluted King's B medium was used (a 1:10 dilution of King's B medium containing 2% proteose-peptone, 1% glycerol, 8.6 mM K2HPO4, and 1 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O [pH 7.2]); K. pneumoniae biofilms were developed in M63 minimal salts (32) supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 14 mM Na3C6H5O7 · 2H2O, and 34 mM l-proline; and for B. cepacia biofilms, M63 minimal salts supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 5% glycerol, and 0.4% Casamino Acids was used. Quantification of biofilm bacteria by CFU was performed as described previously (22, 30). For statistical analyses, P values were determined using Student's t test performed with Microsoft Excel software. Error bars show 1 standard deviation.

Flow cell experiments.

For biofilms grown under flow conditions, bacteria were cultivated in a four-channel flow cell, with square 2- by 2-mm glass capillaries (Friedrich and Dimmock Inc., Millville, NJ) serving as the channels. The flow system was assembled as described previously (8) and inoculated with 18-h LB-grown cultures diluted 10-fold in 30% King's B medium. The medium flow was stopped prior to inoculation and for 1 hour after inoculation. After the development of a mature, multilayered biofilm (24 h following inoculation with P. aeruginosa), the flow was stopped, and the chambers were inoculated with 1 ml (∼1 × 108 PFU/ml) of Micavibrio lysate, prepared as described above, or 1 ml of sterile lysate as a control. After 1 h, the flow was resumed, and DDNB medium was pumped through the flow cell at a constant rate of 4.8 ml/h for the duration of the experiment. The flow cells were incubated at room temperature. The flow was controlled with a PumpPro MPL pump (Watson-Marlow, Cornwall, England). Five experiments were performed for each strain, with two replicates for each treatment.

Imaging.

Epifluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy and viability staining were performed as described previously (22). Quantification of macrocolony formation was performed by visually counting the numbers of macrocolonies in a field of view (magnification, ×100) using phase-contrast microscopy, and at least 50 fields were evaluated for each treatment. Cell clusters with a diameter of >50 μm were considered macrocolonies in this study.

SEM.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) experiments were performed as described previously (22).

Quantitative measurement of aggregation.

The extent of aggregation was measured during growth with the predator according to the method of Burdman et al. (6), modified as described below. The liquid culture containing aggregates was allowed to stand for 20 min to allow aggregates to settle to the bottom of the tube. Turbidity of the suspension (optical density of the suspension [ODs]) was measured using a Molecular Devices VMax kinetic microplate reader (Sunnyvale, CA) at 600 nm. The culture was then dispersed by sonication using a VC505 sonicator (Sonics and Materials Inc., Newtown, CT) for 10 s, and the total turbidity was measured (ODt). The percentage of aggregation was estimated as follows: % aggregation = [(ODt − ODs) × 100]/ODt.

Genetic approach for studying host-predator interaction.

A collection of ∼10,000 random transposon mutants of P. aeruginosa PA14 carrying the transposon Tn5-B30 (Tcr) (31, 39) were grown individually in 96-well microtiter dishes for 18 h to allow biofilm formation and washed three times with DDNB medium, and 100 μl of Micavibrio lysate was added. In a parallel experiment, 100 μl of the sterilized lysate was added to the preformed biofilms. After 24 h of incubation, the wells were stained with crystal violet to assess predation. Biofilm-defective strains among the collection of Tn5-B30 (Tcr) transposon mutants were screened in the lytic halo assay described above.

RESULTS

Host range.

M. aeruginosavorus strain ARL-13 was first isolated some 20 years ago on P. aeruginosa as a host. To reassess the host specificity of M. aeruginosavorus, we analyzed the ability of this predator to attack different bacterial species. M. aeruginosavorus had the ability to attack and form lytic halos on 3 of 19 bacterial species tested (Table 1). The bacteria that were preyed upon by M. aeruginosavorus ARL-13 were B. cepacia, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa, including both strains PA14 and PAO1 and numerous clinical isolates. Liquid lysate assays were performed to confirm predation observed on plates. The predator reduced the host population 100- to 1,000-fold from a starting population of ∼108 CFU/ml by 48 h. No significant reduction in CFU (P > 0.1) was measured in control treatments.

TABLE 1.

Host range of M. aeruginosavorus

| Organism(s) and origin | Predation (no. of attacked strains/no. of strains tested)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Planktonic cellsa | Biofilm cellsb | |

| Acetobacter aceti | − | NA |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | − | NA |

| Burkholderia cepacia | + | + |

| B. cepacia clinical isolate | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | − | NA |

| Erwinia amylovora | −c | NA |

| Escherichia coli | −c | NA |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | +c | + |

| K. pneumoniae clinical isolates | 10/13 | 3/3 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis | − | NA |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 | + | + |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | + | + |

| P. aeruginosa clinical isolates | ||

| Urine | 16/16 | 15/15 |

| Sputa from non-cystic fibrosis patients | 21/27 | 6/13 |

| Sputa from cystic fibrosis patients | 7/11 | 4/4 |

| Eye | 38/43 | 32/34 |

| Miscellaneous organs | 22/23 | 10/15 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | −c | NA |

| Pseudomonas putida | −c | NA |

| Pseudomonas syringae | − | NA |

| Salmonella enterica | −c | NA |

| Serratia marcescens | − | NA |

| Shigella flexneri | − | NA |

| Staphylococcus aureus | − | NA |

| Staphylococcus simulans | − | NA |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | − | NA |

| Vibrio cholerae | − | NA |

Twenty microliters of a Micavibrio lysate (∼1 × 108 CFU/ml) was spotted on a lawn of the indicated bacteria. Predation was scored as the formation of a lytic zone at the point of Micavibrio inoculation. +, predation by M. aeruginosavorus both in the lytic halo assay and in the liquid lysate assay; −, no predation by M. aeruginosavorus.

Biofilms were formed in 96-well microtiter dishes for 18 h, and then the Micavibrio lysate was added to the preformed biofilm. Biofilm reduction was assessed by the reduction of CV staining and CFU counts. +, predation by M. aeruginosavorus; −, no predation by M. aeruginosavorus; NA, not assessed.

Predation by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus 109J.

To further investigate the specificity of the predator, we conducted lytic halo experiments, using clinical isolates as hosts (Table 1). M. aeruginosavorus had the ability to attack 104 of 120 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates tested as well as 10 of 13 K. pneumoniae strains and the one B. cepacia clinical isolate tested. These data show that the predator has some flexibility in its ability to attack strains within a given species. No obvious conserved characteristics, such as colony morphology or excessive exopolysaccharide production, were observed among the resistant strains.

P. aeruginosa biofilm predation assay.

Because M. aeruginosavorus strain ARL-13 was first isolated as a predator of P. aeruginosa, a major opportunistic pathogen and a key model for the study of biofilm formation, we assessed the ability of M. aeruginosavorus to attack biofilms of this microbe. To measure the effect of M. aeruginosavorus on P. aeruginosa biofilms over time, we developed conditions that yielded stable P. aeruginosa biofilms in a 96-well dish. P. aeruginosa biofilms were grown in DNB medium for 18 h. Thereafter, the medium was replaced by DDNB, yielding biofilms comprising ∼1 × 108 CFU/ml that could be maintained stably for up to 144 h.

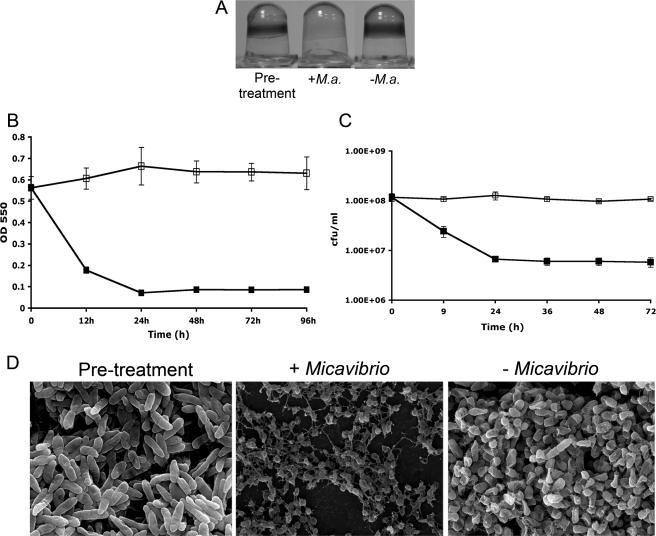

The P. aeruginosa biofilm formed after ∼18 h in a 96-well microtiter plate was exposed to a Micavibrio lysate or a sterile lysate as a control. As shown in Fig. 1A (pretreatment), the untreated 18-h-old biofilm produced was easily visualized by CV staining. Treatment with the Micavibrio lysate (Fig. 1A, +M.a.) markedly reduced the CV staining compared to that of the sterile lysate control (Fig. 1A, −M.a.). Quantification of the effect of M. aeruginosavorus on P. aeruginosa biofilms over time revealed a 69% reduction in CV staining after 12 h and an 87% reduction after 24 h (Fig. 1B, filled squares) relative to that of a biofilm treated with the sterile lysate control. At 48 h, the reduction in CV staining was 85% compared to the initial time point (t = 0), and no further reduction occurred with 96 h of incubation. In contrast, a 13% increase in CV staining in the control was measured after 24 h (Fig. 1B, empty squares).

FIG. 1.

Predation of P. aeruginosa PA14 biofilms by M. aeruginosavorus ARL-13. (A) P. aeruginosa biofilms were developed for 18 h in 96-well microtiter plates (pretreatment), followed by 24 h of exposure to a Micavibrio lysate (+M.a.) or a sterile lysate (−M.a.), and then rinsed and stained with CV. (B) Quantification of biofilm biomass over time. A Micavibrio (▪) or sterile (□) lysate was added to a preformed P. aeruginosa biofilm, the dishes were rinsed and stained with CV, and the amount of CV staining was quantified as the OD550 for each time point. Each value represents the mean for 24 wells from one representative experiment. Error bars show 1 standard deviation. Each experiment was carried out five times, yielding similar results. The difference in OD550 at each time point from 12 h to 96 h was statistically significant (P < 0.001). (C) Quantification of biofilm cell viability. P. aeruginosa biofilms were developed for ∼18 h in a 96-well microtiter plate, followed by exposure to a Micavibrio (▪) or sterile (□) lysate. Samples were obtained after the wells were rinsed and sonicated. Each value represents the mean for three wells from one representative experiment, and error bars indicate standard errors. Each experiment was carried out three times, yielding similar results. The difference in viability between the treatments at each time point was statistically significant (P < 0.001). (D) Scanning electron micrographs after P. aeruginosa biofilms were developed for 18 h on polyvinyl chloride plastic coverslips (pretreatment) and exposed for 24 h to a Micavibrio lysate (+Micavibrio) or a sterile lysate (−Micavibrio). Magnification, ×10,000. Each experiment was performed three times, yielding similar results. Images were viewed at the air-liquid interface.

We also assessed the degree of biofilm decrease by direct enumeration of adherent, viable bacteria. By 24 h, a 16-fold reduction in biofilm cell count, from 1.1 × 108 to 6.6 × 106 CFU/ml, was detected after treatment with M. aeruginosavorus (Fig. 1C, filled squares). The reduction in viable counts of biofilm cells obtained after the first 24 h remained largely unchanged even after an additional 48 h of incubation. In comparison, no reduction in viable biofilm cells was observed in the control wells after 72 h (Fig. 1C, empty squares).

To study the threshold amount of predator needed to reduce biofilm biomass, we varied the total amount of M. aeruginosavorus added to the wells (from 1 × 108 to 1 PFU/well). An initial titer as low as 10 PFU/well was sufficient to reduce a preformed biofilm by 74% after 96 h, as measured by CV staining (from OD550 of 0.6 ± 0.08 to OD550 of 0.18 ± 0.04). To determine if continuous exposure to Micavibrio is necessary for the large decrease in the biofilm population, we monitored the biofilm after a brief exposure (30 min) to ∼1 × 108 PFU of the predator, followed by six washes with saline to remove planktonic Micavibrio. After 24 h, the biomasses of biofilms that were exposed to Micavibrio for 30 min showed nearly the same reduction as that resulting from a continuous 24-h exposure to the predator (78% reduction versus 81% reduction in CV staining, respectively). SEM images taken 30 min after the introduction of Micavibrio, followed by extensive washes to remove unattached cells, confirmed that a 30-min exposure time is sufficient for the predator to attach to cells in the biofilm (data not shown).

Microscopy studies.

To visualize the effect of Micavibrio predation on biofilms, biofilms that were formed on a plastic coverslip were exposed to either a Micavibrio lysate or a sterile lysate control and then analyzed by SEM. A clear difference in the biofilm was observed 24 h after inoculation with the predator compared to inoculation with the control (Fig. 1D). The P. aeruginosa cells remaining in the Micavibrio-treated sample were 74% smaller than the biofilm cells in the control (0.29 ± 0.08 μm and 1.13 ± 0.23 μm in length, respectively; P < 0.001). Furthermore, the amount of cell debris and matrix was much more abundant in the treated sample than in the control. No discernible changes were observed in the control biofilms.

Predation on P. aeruginosa clinical isolate biofilms.

We assessed the ability of the predator to attack biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa clinical isolates. Only 67.5% (81 of 120) of the P. aeruginosa isolates had the ability to form a stable biofilm in a 96-well dish under the conditions tested; Micavibrio had the ability to reduce the biofilms of 67 of these 81 clinical isolates by ≥80% (Table 1).

Biofilm versus planktonic cell susceptibility to Micavibrio attack.

We reported that E. coli biofilms have increased resistance or tolerance to predation by B. bacteriovorus compared to planktonic E. coli cells (22). Therefore, we were interested in investigating whether biofilm-grown P. aeruginosa cells were more resistant to Micavibrio attack than their planktonic counterparts. The survival of planktonic cells was determined by simultaneously inoculating the predator and planktonic P. aeruginosa into DDNB medium in the wells of a microtiter dish. Under these conditions, the planktonic cells are not allowed to form a biofilm before they encounter the predator, and control experiments confirmed that P. aeruginosa does not form biofilms under the conditions tested (data not shown). A small but statistically significant increase (P = 0.04) was noted in the ability of Micavibrio to reduce the number of planktonic cells versus surface-attached cells (from 5.1 × 108 ± 0.2 × 108 to 1.3 × 107 ± 0.5 × 107 CFU/ml for planktonic cells and from 2.1 × 108 ± 0.8 × 108 to 1.3 × 107 ± 0.3 × 107 for biofilm cells).

To confirm that the decrease in planktonic cell population was due to killing by Micavibrio, not to initiation of biofilm formation, we performed the same study described above with a nonmotile flagellar stator P. aeruginosa PA14 mutant (ΔmotABCD) which is incapable of biofilm formation (44). There was no difference in the planktonic growth rate between the wild type and the mutant strain (data not shown) and no significant difference (P > 0.1) in the ability of the predator to reduce the planktonic cell population of the ΔmotABCD mutant (from 2.1 × 108 ± 0.8 × 108 to 1.3 × 107 ± 0.3 × 107) compared to its ability to reduce the wild-type biofilm after 48 h (from 2.5 × 108 ± 0.7 × 108 to 1.1 × 107 ± 0.9 × 107). Additional experiments performed in tubes incubated with agitation also showed no difference in predation between the wild-type and mutant strains (data not shown).

Predation experiments in flow cells.

To assess the resistance of mature biofilms to attack by Micavibrio, we utilized a flow cell system to examine the predation of P. aeruginosa PA14 biofilms. Biofilms were grown in flow cells for 24 h, resulting in a uniform lawn of cells (depth, 12 ± 3 μm). The flow-cell-grown biofilms were inoculated with a single pulse of 1 ml (∼1 × 108 PFU/ml) of Micavibrio lysate, or sterile lysate as a control, and the viability of the cells was assessed 72 h later.

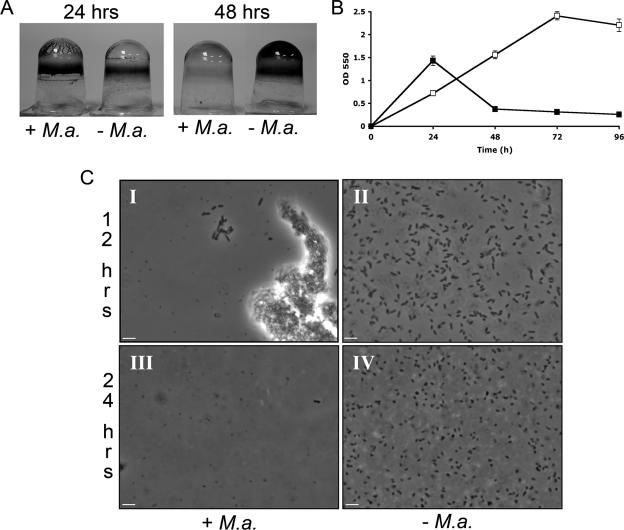

In the control samples, a uniform biofilm lawn was detected by phase-contrast microscopy, with a relatively small number of “mushroom-like” macrocolony structures (Fig. 2, left panels). In contrast, many more macrocolonies were observed for the biofilm treated with Micavibrio. Quantification of these structures revealed a 6.5-fold increase in the number of macrocolonies in the predator-treated sample relative to that in the control (18.2 ± 4.7 and 2.8 ± 1.6 macrocolonies/field, respectively; P < 0.001).

FIG. 2.

Monitoring Micavibrio attack in flow cells. P. aeruginosa PA14 biofilms were developed in a flow cell system for 24 h following inoculation with a Micavibrio (I to III) or sterile (IV to VI) lysate. Seventy-two hours after treatment, the chambers were analyzed by phase-contrast microscopy (I and IV) (dark areas are adherent bacteria) or stained with the BacLight viability stain for 45 min and then rinsed for 45 min to remove excess dye. Syto-9 panels (II and V) indicate viable cells (green, intact membranes), and PI panels (III and VI) indicate dead or compromised cells (red, damaged membranes). Bar, 20 μm; magnification, ×650. Each experiment was performed three times, with two replicates for each treatment, yielding similar results. At least 10 different areas of each sample were examined, and representative images are shown.

By using the BacLight viability stain, it was apparent that for the control samples, the majority of the cells could be considered live (staining green), but for the Micavibrio-treated samples, the vast majority of the cells on the surface and in the macrocolonies were likely dead or had compromised membranes (staining red). OpenLab computer analysis of propidium iodide (PI)-dependent fluorescence measured 3.4 × 104 ± 0.3 × 104 arbitrary fluorescence units after 72 h for the P. aeruginosa biofilm treated with Micavibrio, in contrast to the control, measuring 3.6 × 103 ± 1.6 × 103 arbitrary fluorescence units, which is an ∼10-fold difference (P < 0.001).

Cell-cell interactions are induced by predation.

The flow cell studies showed an increase in macrocolony formation in the predator-treated sample compared to that in the control, indicating that M. aeruginosavorus impacted the multicellular behavior of P. aeruginosa. We found that in rich medium (such as King's B medium), rather than the nutrient-limited conditions used in the planktonic cell susceptibility assay described above, the addition of Micavibrio induced P. aeruginosa biofilm formation at early time points. Microtiter wells were inoculated (100 μl per well) with 18-h LB-grown P. aeruginosa cells diluted 1:50 in 10% King's B medium and mixed at a 1:1 ratio with a Micavibrio lysate or a sterile lysate as the control. There was a 50% increase in CV staining in the treated sample (Fig. 3A, +M.a.) compared to that in the control (Fig. 3A, −M.a.) at 24 h of incubation. This was followed by a reduction in CV staining of 78% in the predator-treated sample (Fig. 3A, 48h, +M.a.) and a 53% increase in CV staining in the control (Fig. 3A, 48 h, −M.a.).

FIG. 3.

Predation promotes early biofilm formation and cell aggregation. (A) P. aeruginosa biofilms were simultaneously mixed with a Micavibrio (+M.a.) or sterile (−M.a.) lysate, and the wells were rinsed and stained with CV after 24 and 48 h of incubation. (B) Quantification of biofilm biomass over time. A Micavibrio (▪) or sterile (□) lysate was simultaneously mixed with P. aeruginosa cells, the dishes were rinsed and stained with CV, and the amount of CV staining was quantified as the OD550 for each time point. Each value represents the mean for 24 wells from one representative experiment, and error bars indicate 1 standard deviation. Each experiment was carried out five times, yielding similar results. The difference in OD550 at each time point from 24 h to 96 h was statistically significant (P < 0.001). (C) Phase-contrast microscopy images taken 12 (I and II) and 24 (III and IV) h after P. aeruginosa was simultaneously mixed with a Micavibrio lysate (+M.a.) or sterile lysate (−M.a.). Bar, 4 μm; magnification, ×650. This experiment was performed three times, yielding similar results.

Additional verification of the dynamics of biofilm development in the presence of the predator came from direct enumeration of adherent, viable bacteria (Fig. 3B). By 24 h, the number of biofilm CFU in the Micavibrio-treated sample was 3.4-fold higher than that in the control (3.4 × 108 ± 0.7 × 108 and 1.0 × 108 ± 0.1 × 108 CFU/ml, respectively; P < 0.01), followed by a reduction in the treated sample (9.5 × 107 ± 0.1 × 107 CFU/ml) and an increase in the control sample (1.0 × 109 ± 2.0 × 109 CFU/ml) after 48 h. Therefore, the results of assays in 96-well dishes mirror those of assays in flow cells, with an initial boost in biofilm formation followed by a reduction of the viable population for the Micavibrio-treated sample.

One possibility for the increase in biofilm formation at earlier time points is that cell debris produced by predation became available to the host, thereby stimulating host growth and biofilm formation. We predicted that if this were the case, we would also expect to observe an increase in the planktonic P. aeruginosa population at early time points after addition of the predator. To evaluate this hypothesis, we conducted experiments in which host cells and Micavibrio were simultaneously mixed in 5-ml tubes and grown under shaking conditions. There was no growth increase in planktonic P. aeruginosa measured in the predator-treated sample during the first 18 h of predation (from 1.3 × 108 ± 0.2 × 108 to 5.5 × 105 ± 1.2 × 105 CFU/ml), but an increase in viable P. aeruginosa cells was detected in the sterile lysate control treatment (from 5.6 × 107 ± 3.1 × 107 to 3.5 × 109 ± 1.2 × 109 CFU/ml). These data are not consistent with the hypothesis that the increased biofilm formation in the presence of Micavibrio is due to increased growth of P. aeruginosa. We also observed no difference in the growth of P. aeruginosa when the Micavibrio lysate versus a filter-sterilized supernatant of a P. aeruginosa culture was used as growth medium.

In analyzing predation by phase-contrast microscopy, it was quite evident that most of the host cells in the Micavibrio-treated sample formed aggregates within the first few hours, whereas no cell aggregation was observed in the control sample or in a sample that was mixed with heat-killed Micavibrio cells (incubated for 45 min at 65°C). By 12 h, a decrease in host cell number and an increase in predator cell population were clearly noted in the Micavibrio-treated sample, with most of the host cells being aggregated (Fig. 3C, +M.a., panel I). In contrast, many more individual P. aeruginosa cells were observed in the control sample, with no cell aggregation observed by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 3C, −M.a., panel II). Measuring the extent of aggregation revealed a significant difference (P < 0.01) in aggregation between the samples, with 4.6% ± 1.7% aggregation measured for the control and 18.2% ± 3.3% aggregation measured for the Micavibrio-treated sample. Only a very few P. aeruginosa cells were detected by microscopy after 24 h of incubation with the predator, in contrast to the control, where a large number of cells were clearly visible (Fig. 3C, +M.a., panel III, and −M.a., panel IV, respectively). These micrographs confirmed the quantitative analysis shown above. Taken together, these results suggest that the increase in biofilm formation observed at early time points in the Micavibrio-treated sample is not likely to be caused by stimulation of cell growth but is due instead to an increase in cell-cell interactions brought about by the presence of the live predator or active predation.

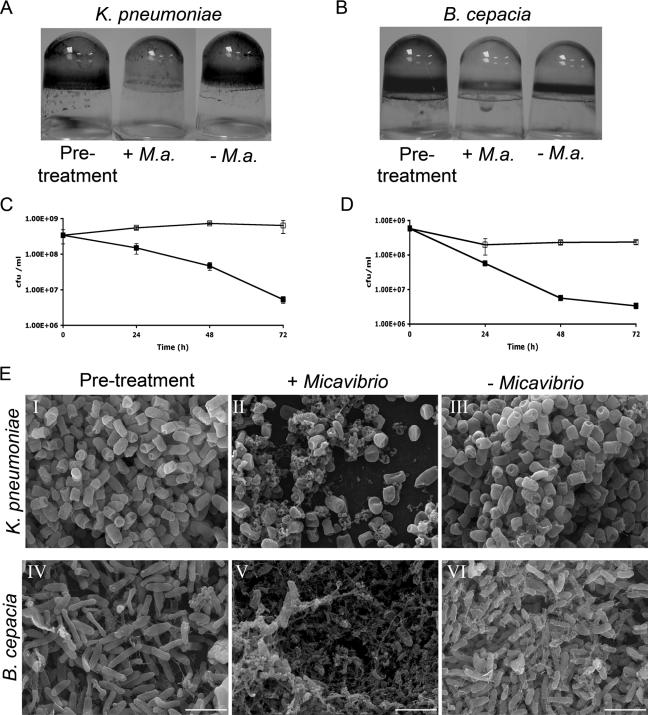

Predation of Micavibrio on K. pneumoniae and B. cepacia biofilms.

Our experiments showed that M. aeruginosavorus has the ability to attack both K. pneumoniae and B. cepacia in liquid culture (Table 1). To determine the ability of the predator to attack biofilms composed of these bacteria, we identified strains that had the ability to form stable and robust biofilms in a 96-well dish for extended time periods, including three clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae (1840, 1867, and 1868) and two isolates of B. cepacia (a clinical isolate and ATCC 25416). Because initial testing confirmed that M. aeruginosavorus could attack 18-h biofilms of these selected isolates equally well (data not shown), one isolate of each species was chosen for the subsequent experiments (K. pneumoniae isolate 1840 and B. cepacia ATCC 25416).

K. pneumoniae and B. cepacia biofilms were formed for 18 h, and then the medium was removed and replaced with DDNB medium containing a Micavibrio lysate or a sterile lysate as a control. The untreated 18-h-old biofilm produced by each strain was visualized by CV staining (Fig. 4A and B, pretreatment). Treatment with M. aeruginosavorus (Fig. 4A and B, +M.a.) markedly reduced the CV staining for each strain compared to that of the control (Fig. 4A and B, −M.a.). These data were confirmed by direct enumeration of adherent, viable bacteria (Fig. 4C and D). We also assessed the ability of M. aeruginosavorus to attack preformed biofilms of K. pneumoniae and B. cepacia clinical isolates. Micavibrio had the ability to reduce the biofilms of all K. pneumoniae isolates tested (three of three) as well as those of the single clinical isolate of B. cepacia examined (Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Predation on K. pneumoniae and B. cepacia biofilms by M. aeruginosavorus ARL-13. (A) K. pneumoniae and (B) B. cepacia biofilms were developed for 18 h in 96-well microtiter plates (pretreatment), followed by 24 h of exposure to a Micavibrio lysate (+M.a.) or a sterile lysate (−M.a.), and then rinsed and stained with CV. (C and D) Quantification of biofilm cell viability. K. pneumoniae (C) and B. cepacia (D) biofilms were developed for ∼18 h in 96-well microtiter plates, followed by exposure to a Micavibrio lysate (▪) or a sterile lysate (□), and biofilm cell viability was assessed as described in the legend for Fig. 1. The difference in viability between the treatments at each time point was statistically significant (P < 0.01). (E) Scanning electron micrographs taken after K. pneumoniae (I to III) and B. cepacia (IV to VI) biofilms were developed for 18 h on polyvinyl chloride plastic coverslips (I and IV, pretreatment) and exposed for 24 h to a Micavibrio lysate (II and V, + Micavibrio) or a sterile lysate (III and VI, − Micavibrio). Bar, 4 μm; magnification, ×10,000. Each experiment was performed three times, yielding similar results. Images were viewed at the air-liquid interface.

The effect of Micavibrio predation on K. pneumoniae and B. cepacia biofilms was visualized by SEM imaging. Again, a clear difference in biofilms was observed 24 h after inoculation with the predator compared to inoculation with the control (Fig. 4E). In the Micavibrio-treated sample, the number of intact cells was noticeably reduced, with much more cell debris and matrix (Fig. 4E, panels II and V, + Micavibrio), with no discernible changes observed for the biofilm in the control treatment (Fig. 4E, panels III and VI, − Micavibrio).

Genetic screen to identify loci important for host-predator interactions.

In an attempt to identify genes required for the host-predator interaction, we screened a transposon mutant library of P. aeruginosa organisms grown as biofilms for mutants resistant to Micavibrio attack. Micavibrio had the ability to attack and reduce all mutant strains tested, as assessed by CV staining. The biofilm-negative strains among the ∼10,000 mutants were also tested in the lytic halo assay and shown to be susceptible to attack by Micavibrio. No reduction in CV staining was observed in the sterile lysate control (data not shown), and an 85% decrease was observed for the wild-type P. aeruginosa biofilm treated with a Micavibrio lysate used as a positive control.

DISCUSSION

In a previous study, we showed that the predatory bacterium B. bacteriovorus could attack and reduce existing E. coli and P. fluorescens biofilms (22). For this work, we were interested in determining whether we could employ predatory prokaryotes against P. aeruginosa biofilms. Preliminary testing had shown that B. bacteriovorus 109J is limited in its ability to decrease existing P. aeruginosa biofilms (unpublished data). Reevaluating the host specificity of M. aeruginosavorus ARL-13 revealed that, as previously described (25), this exoparasite has the ability to attack lab strains as well as numerous clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. Furthermore, M. aeruginosavorus ARL-13 also attacked two other opportunistic human pathogens, namely, B. cepacia and K. pneumoniae (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

While Micavibrio species typically exhibit relatively narrow host ranges (2, 25), under suboptimal storage conditions these predators may lose species specificity and become parasites with a broad host spectrum. For example, Micavibrio admirandus ARL-14 lost its host specificity after a 3-year storage period in liquid culture, in which it was reseeded numerous times (1). In our experiments, M. aeruginosavorus ARL-13 was grown under suitable conditions and still maintained a restricted host range. Thus, we believe that B. cepacia and K. pneumoniae can naturally be preyed upon by ARL-13 and that predation was not brought about by a breach in host specificity. However, this point needs to be investigated further using additional M. aeruginosavorus strains when they become available.

A microtiter dish-based static assay was used to monitor the ability of Micavibrio to attack P. aeruginosa PA14, B. cepacia, and K. pneumoniae biofilms as well as biofilms derived from several clinical isolates. Both CV staining and viable counts showed that Micavibrio was capable of markedly reducing biofilm biomass (Fig. 1 and 4). The extent of damage brought about by M. aeruginosavorus on biofilms was further visualized by SEM imaging, wherein the bulk of the biofilm cells were shown to be destroyed, leaving behind what appears to be cell residue and matrix. An initial titer of as low as 10 PFU/well of Micavibrio was sufficient to reduce P. aeruginosa biofilms by 75% after 96 h, and furthermore, biofilm-attached Micavibrio visualized by SEM imaging 30 min after initial inoculation confirmed that this brief exposure period was sufficient to initiate infection.

We reported that E. coli biofilms exhibit an increase in resistance towards Bdellovibrio attack compared to a planktonic population of the same bacterium (22). In this work, we did not observe a marked difference between the abilities of Micavibrio to attack P. aeruginosa cells as biofilms and as free-floating cells. This outcome could be explained by the inability of the predator to completely eradicate its planktonic prey, as previously demonstrated for bdellovibrios (23). Another explanation may be that under the conditions tested, biofilm formation does not enhance the ability of P. aeruginosa to withstand predation compared to that of planktonic cells. This observation holds promise that Micavibrio treatment may be effective for reducing P. aeruginosa biofilms, at least under some conditions.

P. aeruginosa has the ability to adapt to environmental predators, such as grazing protozoa, by developing grazing-resistant macrocolonies (29). By concurrently incubating P. aeruginosa and M. aeruginosavorus in a rich medium, we were able to study P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and its response to Micavibrio attack. A more robust biofilm was formed in the presence of the predator than in the control lacking Micavibrio, followed by a decrease in biofilm biomass in the Micavibrio-treated sample and a biofilm increase in the control, as measured by both CV staining and viable counts (Fig. 3 and related text). By growing P. aeruginosa with and without Micavibrio in liquid cultures, we showed that there is no increase in the host planktonic population in response to predation, and thus the biofilm increase is not likely to be a consequence of an increased number of planktonic cells in the system. However, we did note an increase in cell-cell interactions in the Micavibrio-treated sample (Fig. 3C). This aggregation phenomenon was detected only when the host was mixed with live predator and did not occur when heat-killed Micavibrio or filtered sterilized lysate was added. At this point, we cannot determine if the increase in aggregation is an active process or is merely an indirect occurrence caused by an increase in cell debris, extracellular DNA, etc. Our results also suggest that under certain conditions, perhaps in which P. aeruginosa is provided with sufficient nutrients, this microbe can adapt to attack by increasing biofilm formation, as was also recently shown for protozoan grazers of P. aeruginosa biofilms (29). Weitere et al. (45) demonstrated that P. aeruginosa PAO1 macrocolonies confer only partial protection against protozoan grazers. This work is consistent with our finding that while Micavibrio predation did bring about an increase in the formation of macrocolonies by P. aeruginosa PA14, these biofilms were still susceptible to Micavibrio attack (Fig. 2).

An early study of M. admirandus demonstrated that certain carbohydrates inhibited the initial interactions between the host and predator, thus preventing predation. These data indicated that the host-predator interaction might be mediated by the availability of sugar receptors on one of the partners (7). In an attempt to identify genes required for host-predator interaction in our system, we screened ∼10,000 P. aeruginosa PA14 transposon mutants grown as biofilms to identify strains resistant to attack by Micavibrio. No predation-resistant mutants were isolated from this initial screen. At this point, we can only speculate about the reason that no resistant mutants were identified. For example, a putative receptor responsible for host-predator interaction may be essential, or genes or pathways required for these interactions are redundant. Finally, we are aware that our screen is not yet fully saturated.

With the increasing interest in developing improved methods for controlling biofilms, there are many potential advantages of using M. aeruginosavorus for the biological control of P. aeruginosa biofilms, including the following: (i) it could be assumed that the narrow host range and specificity for infecting bacteria cells demonstrated so far might indicate that Micavibrio is harmless to commensal and nonbacterial organisms, (ii) Micavibrio's ability to feed on the host allows the use of low initial doses to carry out an attack, and (iii) the toxins secreted by P. aeruginosa do not seem to inhibit Micavibrio's ability to prey on this host, as is the case with other predators (29, 45). Furthermore, our data indicate that growth in a biofilm does not confer any additional protection to P. aeruginosa compared to growth as a planktonic population, suggesting that M. aeruginosavorus may be able to overcome some aspects of biofilm-mediated resistance. Future work using the methods developed in this work should allow us to broaden our understanding of factors important for host-predator interactions and the host-specific response to Micavibrio attack, as well as to perform a more rigorous assessment of the potential use of Micavibrio as a biocontrol agent for biofilms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edouard Jurkevitch from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for kindly providing us with the M. aeruginosavorus ARL-13 strain, Joseph Schwartzman and Regis Kowalski for the clinical isolates, and R. Kolter, R. Taylor, and M. Klotz for additional strains. We also thank Charles Daghlian and the Ripple Electron Microscopy facility at Dartmouth College for assistance with the SEM studies.

This research was supported by funding from the NIH (AI55774-01) and NSF (NSF9984521) to G.A.O.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afinogenova, A. V., S. M. Konovalova, and V. A. Lambina. 1986. Loss of trait of species monospecificity by exoparasitic bacteria of the genus Micavibrio. Microbiology 55:377-380. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afinogenova, A. V., N. Markelova, and V. A. Lambina. 1987. Analysis of the interpopulational interactions in a 2-component bacterial system of Micavibrio admirandus-Escherichia coli. Nauchn. Dokl. Vyssh. Shk. Biol. Nauki 6:101-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asaduzzaman, M., E. T. Ryan, M. John, L. Hang, A. I. Khan, A. S. Faruque, R. K. Taylor, S. B. Calderwood, and F. Qadri. 2004. The major subunit of the toxin-coregulated pilus TcpA induces mucosal and systemic immunoglobulin A immune responses in patients with cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Infect. Immun. 72:4448-4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher, R. C. 2004. New concepts of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 23:146-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooun, A., S. Liu, and K. Lewis. 2000. A dose-response study of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:640-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burdman, S., E. Jurkevitch, B. Schwartsburd, M. Hampel, and Y. Okon. 1998. Aggregation in Azospirillum brasilense: effects of chemical and physical factors and involvement of extracellular components. Microbiology 144:1989-1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chemeris, N. A., and A. V. Afinogennova. 1986. Role of carbohydrate receptors in the interaction of Micavibrio admirandus and host-bacterium. Zentbl. Mikrobiol. 141:557-560. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen, B. B., C. Sternberg, J. B. Andersen, L. Eberl, S. Moller, M. Givskov, and S. Molin. 1998. Establishment of new genetic traits in a microbial biofilm community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2247-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costerton, J. W., Z. Lewandowski, D. E. Caldwell, D. R. Korber, and H. M. Lappin-Scott. 1995. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:711-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtin, J. J., and R. M. Donlan. 2006. Using bacteriophages to reduce formation of catheter-associated biofilms by Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1268-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davey, M. E., and G. A. O'Toole. 2000. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:847-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidov, Y., D. Huchon, S. F. Koval, and E. Jurkevitch. 2006. A new-proteobacterial clade of Bdellovibrio-like predators: implications for the mitochondrial endosymbiotic theory. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6757-6765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donlan, R. M., and J. W. Costerton. 2002. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:167-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doolittle, M. M., J. J. Cooney, and D. E. Caldwell. 1995. Lytic infection of Escherichia coli biofilms by bacteriophage T4. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:12-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doolittle, M. M., J. J. Cooney, and D. E. Caldwell. 1996. Tracing the interaction of bacteriophage with bacterial biofilms using fluorescent and chromogenic probes. J. Ind. Microbiol. 16:331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunne, W. M., Jr. 2002. Bacterial adhesion: seen any good biofilms lately? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:155-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fratamico, P. M., and P. H. Cooke. 1996. Isolation of bdellovibrios that prey on Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella species and application for removal of prey from stainless steel surfaces. J. Food Saf. 16:161-173. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall-Stoodley, L., J. W. Costerton, and P. Stoodley. 2004. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:95-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanlon, G. W., S. P. Denyer, C. J. Olliff, and L. J. Ibrahim. 2001. Reduction in exopolysaccharide viscosity as an aid to bacteriophage penetration through Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2746-2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoyle, B. D., and W. J. Costerton. 1991. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics: the role of biofilms. Prog. Drug Res. 37:91-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes, K. A., I. W. Sutherland, J. Clark, and M. V. Jones. 1998. Bacteriophage and associated polysaccharide depolymerases—novel tools for study of bacterial biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85:583-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadouri, D., and G. A. O'Toole. 2005. Susceptibility of biofilms to Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus attack. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4044-4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keya, S. O., and M. Alexander. 1975. Regulation of parasitism by host density: the Bdellovibrio-Rhizobium interrelationship. Soil Biol. Biochem. 7:231-237. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambina, V. A., A. V. Afinogenova, S. Romai Penabad, S. M. Konovalova, and A. P. Pushkareva. 1982. Micavibrio admirandus gen. et sp. nov. Mikrobiologiia 51:114-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambina, V. A., A. V. Afinogenova, Z. Romay Penobad, S. M. Konovalova, and L. V. Andreev. 1983. New species of exoparasitic bacteria of the genus Micavibrio infecting gram-positive bacteria. Mikrobiologiia 52:777-780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mah, T. F., and G. A. O'Toole. 2001. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 9:34-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mah, T. F., B. Pitts, B. Pellock, G. C. Walker, P. S. Stewart, and G. A. O'Toole. 2003. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature 426:306-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattison, R. G., and S. Harayama. 2001. The predatory soil flagellate Heteromita globosa stimulates toluene biodegradation by a Pseudomonas sp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 194:39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matz, C., T. Bergfeld, S. A. Rice, and S. Kjelleberg. 2004. Microcolonies, quorum sensing and cytotoxicity determine the survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms exposed to protozoan grazing. Environ. Microbiol. 6:218-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merritt, J. H., D. E. Kadouri, and G. A. O'Toole. 2005. Growing and analyzing static biofilms, p. 1B.1.1-1B.1.17. Current protocols in microbiology, vol. 1. J. Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30:295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pardee, A. B., F. Jacob, and J. Monod. 1959. The genetic control and cytoplasmic expression of “inducibility” in the synthesis of β-galactosidase in E. coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1:165-178. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parry, J. D. 2004. Protozoan grazing of freshwater biofilms. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 54:167-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parsek, M. R., and P. K. Singh. 2003. Bacterial biofilms: an emerging link to disease pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:677-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel, R. 2005. Biofilms and antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 437:41-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Post, J. C., P. Stoodley, L. Hall-Stoodley, and G. D. Ehrlich. 2004. The role of biofilms in otolaryngologic infections. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 12:185-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pratt, L. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli biofilm formation: roles of flagella, motility, chemotaxis and type I pili. Mol. Microbiol. 30:285-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sibille, I., T. Sime-Ngando, L. Mathieu, and J. C. Block. 1998. Protozoan bacterivory and Escherichia coli survival in drinking water distribution systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:197-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon, R., J. Quandt, and W. Klipp. 1989. New derivatives of transposon Tn5 suitable for mobilization of replicons, generation of operon fusions and induction of genes in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 80:160-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh, P. K., A. L. Schaefer, M. R. Parsek, T. O. Moninger, M. J. Welsh, and E. P. Greenberg. 2000. Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407:762-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starr, M. P. 1975. Bdellovibrio as symbiont; the associations of Bdellovibrios with other bacteria interpreted in terms of a generalized scheme for classifying organismic associations. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 29:93-124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stolp, H., and M. P. Starr. 1963. Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus gen. et sp. n., a predatory, ectoparasitic, and bacteriolytic microorganism. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 29:217-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suthereland, I. W., K. A. Hughes, L. C. Skillman, and K. Tait. 2004. The interaction of phage and biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 232:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toutain, C. M., M. E. Zegans, and G. A. O'Toole. 2005. Evidence for two flagellar stators and their role in the motility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 187:771-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weitere, M., T. Bergfeld, S. A. Rice, C. Matz, and S. Kjelleberg. 2005. Grazing resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms depends on type of protective mechanism, developmental stage and protozoan feeding mode. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1593-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zubkov, M. V., and M. A. Sleigh. 1999. Growth of amoebae and flagellates on bacteria deposited on filters. Microb. Ecol. 37:107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]