Abstract

Objective

To examine how the financial pressures resulting from the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 interacted with private sector pressures to affect indigent care provision.

Data Sources/Study Setting

American Hospital Association Annual Survey, Area Resource File, InterStudy Health Maintenance Organization files, Current Population Survey, and Bureau of Primary Health Care data.

Study Design

We distinguished core and voluntary safety net hospitals in our analysis. Core safety net hospitals provide a large share of uncompensated care in their markets and have large indigent care patient mix.

Voluntary safety net hospitals provide substantial indigent care but less so than core hospitals. We examined the effect of financial pressure in the initial year of the 1997 BBA on uncompensated care for three hospital groups. Data for 1996–2000 were analyzed using approaches that control for hospital and market heterogeneity.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

All urban U.S. general acute care hospitals with complete data for at least 2 years between 1996 and 2000, which totaled 1,693 institutions.

Principal Findings

Core safety net hospitals reduced their uncompensated care in response to Medicaid financial pressure. Voluntary safety net hospitals also responded in this way but only when faced with the combined forces of Medicaid and private sector payment pressures. Nonsafety net hospitals did not exhibit similar responses.

Conclusions

Our results are consistent with theories of hospital behavior when institutions face reductions in payment. They raise concern given continuing state budget crises plus the focus of recent federal deficit reduction legislation intended to cut Medicaid expenditures.

Keywords: Hospital safety net, uncompensated care

Hospitals in the U.S. have traditionally provided substantial amounts of charity and discounted care to indigent patients (Melnick, Mann, and Bamezai 2000; Hadley and Holahan 2003). Several policy and market changes during the late 1990s, however, weakened the financial position of some hospitals, and this most likely affected their ability to provide indigent care. In particular, the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 included several provisions affecting hospital Medicare and Medicaid payments. Medicare payments were trimmed through limits on inpatient DRG inflation adjustments, reductions in medical education and disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payment adjustments, and by changes in payment methods for capital expenses, outpatient services, and home health. BBA also established state-by-state Medicaid DSH spending limits for 1998–2002 (Rosenbaum and Darnell 1997). BBA was subsequently revised and about 17.6 percent of hospital Medicare payment cuts were restored and Medicaid DSH limits for 2001 and 2002 were raised. However, this relief was temporary because the 1999 and 2000 BBA amendments expired in 2003.

In addition to BBA-related stresses, an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the health safety net identified several other “troubling trends” (Lewin and Altman 2000, pp. 4–6), including persistently high percentages of individuals who are uninsured and growing managed care pressures. Guterman (2000) remarked that never before had such strong financial pressures from both public and private sectors simultaneously come to bear on hospitals. The objective of this paper is to examine how BBA financial pressures in conjunction with private payer pressures affected the involvement of urban hospitals in local health safety nets.

On the basis of the results of existing research, we would expect reductions in indigent care among certain groups of hospitals given the financial pressures described above. Atkinson, Helms, and Needeleman (1997) and Cunningham and Tu (1997) reported the stagnation or decline in hospital resources devoted to uncompensated care by voluntary nonprofit hospitals through the 1990s despite continued growth in the number of uninsured individuals. Findings from Gaskin (1997), Davidoff et al. (2000), Thorpe, Seiber, and Florence (2001), and Rosko (2004) suggest that nonprofit hospitals reduced their uncompensated care as health maintenance organization (HMO) market share increased and/or as payment generosity declined. Campbell and Ahern (1993) and Mann et al. (1997) also found that lower Medicaid or Medicare payments led to reductions in uncompensated care.

One problem with these studies is that they have generally assumed that voluntary nonprofit hospitals represent a form of back-up capacity to public and major teaching hospitals in indigent care provision. However, use of organizational labels to identify safety net hospitals is problematic because substantial within-category variation may exist in commitment to indigent care. Our study identifies and assesses uncompensated care provision based on the demonstrated prior involvement of urban hospitals in these activities.

IDENTIFICATION OF SAFETY NET HOSPITALS

We followed approaches of Zuckerman et al. (2001) to operationalize the definition of the safety net developed in the 2000 IOM report. The IOM defined safety net providers as those that are organized to deliver “significant” levels of health care and other related services to indigent patients (Lewin and Altman 2000). Zuckerman et al. (2001) defined “significant” from two particular perspectives: (1) significant from the hospital's perspective in that a large share of hospital resources, as measured by hospital expenses, was devoted to care of the indigent; and (2) significant from the community's perspective in that the hospital provided care for a substantial share of a community's indigent population. Following the earlier study, we used the top decile of the percent of hospital expenses that were uncompensated as the threshold to identify hospitals devoting significant resources to uncompensated care. We also followed their approach of computing a hospital's adjusted market share of uncompensated care expenses in its metropolitan statistical area (MSA) and using it to identify significant indigent care providers.

We identified the subset of safety net hospitals that had both large adjusted market shares of uncompensated care and large portions of their hospital expenses that were uncompensated and designated them as core safety net hospitals. Indigent patients make up a large share of these hospitals' patient populations by virtue of the high percentage of their expenses that are uncompensated. They are also critical institutions in their communities by virtue of their large adjusted market share of uncompensated care. All other safety net hospitals we identified were deemed voluntary safety net hospitals.

We used 1995 uncompensated care data from the American Hospital Association (AHA) to identify safety net hospitals for our analysis. Hospital safety net designation in that year was retained throughout the 1996–2000 study period over which we examined changes in uncompensated care provision. We used 1995 rather than 1996 uncompensated care data to identify safety net hospitals to mitigate potential regression to the mean effects.1

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Our primary objective is to assess how financial pressure resulting from BBA-induced changes in Medicare and Medicaid payments affected hospital provision of indigent care. To help motivate the analysis, we turned to existing theoretical frameworks. Hoerger (1991) modeled nonprofit hospitals as maximizing the quantity and/or quality of services they produce subject to a budget constraint that allowed for the realization of a target profit level. Exogenous policy changes, such as Medicare or Medicaid payment reductions, affect the ability of a hospital to reach its target profit. Thus, government and voluntary nonprofit hospitals may cut-back on the quality of care or the provision of indigent care to increase the likelihood of achieving their target profit level. This expectation is consistent with Frank and Salkever (1991), who suggested that utility maximizing hospitals reduce the amount of indigent care they provide as their net revenues decline. Overall, we expect that the motivations and behavior of both core and voluntary safety net hospitals will be consistent with these expectations and hypothesize:

H1: Core and voluntary safety net hospitals will reduce their uncompensated care provision in response to Medicare or Medicaid payment pressures.

In relation to hospitals classified as nonsafety net institutions, we expect that the theoretical model developed by Banks, Paterson, and Wendel (1997) explains their reaction to a payment change. The priorities of these hospitals are heavily focused on generating profits. However, Banks and colleagues noted that these hospitals are subject to expectations about providing some minimum amount of indigent care and may lose business if they do not meet these expectations. In particular, hospitals face federal regulations about treating emergency cases regardless of patient insurance status and also possibly certificate-of-need requirements or expectations based on tax exemptions. Banks et al. (1997) hypothesized that these hospitals may in fact increase uncompensated care provision as payment generosity for paying patients declines because the cost of meeting community expectations, in terms of foregone profit, is lower. Davidoff et al. (2000) noted this effect may be small or insignificant if the financial benefits of meeting community expectations are low. Given this we hypothesize:

H2: Nonsafety net hospitals may increase their uncompensated care provision in response to Medicare and Medicaid payment pressures, although this effect may not be substantial.

Thus far, we have discussed hospital response to declining Medicare and Medicaid profits without reference to the market conditions they face. In markets where private payers exert a strong influence on market prices, such as those dominated by HMOs, hospitals can face substantial private sector financial pressures. The combined effects of this private sector pressure and declining public payment generosity can create great difficulty for voluntary and core safety net hospitals in meeting their profit targets. Given this, we expect:

H3: Voluntary and core safety net hospitals in markets with high HMO market share will likely make more substantial cuts in uncompensated care in response to Medicare and Medicaid payment pressures.

It is unclear whether the presence of private payer pressure will affect the response of nonsafety net hospitals to Medicare and Medicaid payment declines. Hoerger (1991) suggests little response for these hospitals regardless of market conditions. However, based on Banks et al. (1997), private sector pressures in conjunction with reductions in public payments imply that nonsafety net hospitals forego less revenue when meeting community expectations and thus may expand indigent care provision.

DATA AND EMPIRICAL METHODS

A major source of data for our analysis was the AHA Annual Surveys. The AHA data provide information not only on hospital uncompensated care but also a variety of organizational and operational characteristics. We also obtained Uniform Data System of the Bureau of Primary Health Care on Federally Qualified Community Health Centers (FQHCs). Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services data were used to measure Medicaid managed care enrollment, and InterStudy data of HMO enrollment (corrected for home office reporting problems) were used to measure HMO market share. Area Resource File and Current Population Survey data were used to measure community demographics likely to affect local need for indigent care. Data from these sources were merged for the period 1996–2000. We defined markets based on the geopolitical boundaries of MSAs.

Study Sample

Our analysis focused on urban, short-term general acute care hospitals for which we could define safety net status in 1995 and which were in operation for at least 2 years between 1996 and 2000. We further limited the sample to hospitals located in markets where there were either core safety net hospitals or FQHCs in operation. These markets hold potential for voluntary safety net and nonsafety net hospitals to reduce their indigent care involvement because committed alternative providers are present. In total, we had complete data on 1,693 hospitals, of which 90 (5.3 percent) were core safety net hospitals, 244 (14.4 percent) were voluntary safety net hospitals, and 1,359 (80.3 percent) were classified as nonsafety net hospitals.

Empirical Model

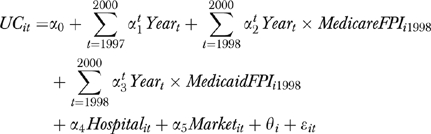

The general specification of our model is

|

(1) |

where UC represents our measures for hospital uncompensated care, with i indexing a hospital and t indexing time. Because the AHA reports uncompensated care as charges, we used an institutional cost to charge ratio to convert these amounts to costs. We used two alternative measures for UC based on prior research: (1) the log of annual hospital uncompensated care costs and (2) the percent of hospital expenses that are uncompensated.

MedicareFPIi1998 and MedicaidFPIi1998 are measures of financial pressure induced when BBA provisions were first implemented in 1998. We reviewed a number of studies that measured financial pressure resulting from the transition to the Medicare Prospective Payment System to create measures for our analysis. In particular, Zwanziger and Melnick (1988) measured financial pressure by multiplying a hospital's Medicare cost to payment ratio with its Medicare share of hospital inpatients. Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai (2000) later refined this basic approach by subtracting one from the cost to payment ratio before multiplying it by Medicare's patient share. Hadley, Zuckerman, and Feder (1989) developed a similar measure in which Medicare potential profits per case (i.e., revenues less costs) were multiplied by Medicare discharges and then divided by hospital total expenses. They indicated that “… conceptually, the index is an estimate of the overall profit or loss a hospital might anticipate from treating Medicare inpatients if it made no changes in the costs of providing care, the volume of Medicare cases, or its total expenses” (p. 356).

We used a hybrid of Hadley et al. (1989) and Zwanziger et al. (2000) to assess BBA financial pressure. In particular, our formula for MedicareFPIi1998 is

| (2) |

which consists of hospital i's Medicare costs per adjusted admission (MCC) in 1997, total Medicare revenues measured per adjusted Medicare admission (MRC) in 1998, an estimate of Medicare adjusted admissions in 1997 (MCRADJ), and total hospital expenses (TE) in 1997. We used adjusted admissions rather than inpatient discharges to construct our FPI because adjusted admissions account for both outpatient and inpatient care, and the former has become a larger portion of hospital output mix since the 1980s.2 We used the same formula in (2) to construct our financial pressure measure for Medicaid payments.

Following the approach of Zwanziger et al. (2000), we measured financial pressure at the time the policy intervention was initiated (i.e., 1998) and examined its effect using interaction terms with year dummy variables for 1998–2000. In 1998, BBA implemented major changes in Medicare and Medicaid payments, including a freeze on Medicare DRG payments despite a 4.7 percent increase in Medicare costs per discharge in that year (MedPAC 2004), reductions in Medicare DSH and IME, and a Medicaid DSH freeze.

A potential concern about the construction of the FPI measures and our dependent variable is that both rely on measures of hospital revenues and expenses. Namely, the dependent variable uses a cost to gross patient charge ratio to translate annual uncompensated care charges into costs, and the FPIs use the difference between costs and net patient revenues to measure financial pressure. A hospital that has high costs relative to gross charges (and thus presumably high costs to net patient revenues) would likely have higher uncompensated costs and higher FPIs in a given year when compared with a hospital with lower relative costs, ceteris paribus. However, we measure FPIs in 1 year (1998) and this measure is fixed over time in the regression analysis. In contrast, we measure uncompensated care annually and allow it to vary over time in the regression analysis. This limits the extent to which a spurious relationship in measures may arise, though it does not completely eliminate the potential bias. Any bias that results, though, runs counter to our stated hypotheses that a negative (rather than positive) relationship exists between FPI and uncompensated care for safety net hospitals. The effect this will have on our ability to assess a relationship between FPI and uncompensated care for nonsafety net hospitals is unclear because we expect a minimal relationship between the two.

Our tests for whether BBA influenced hospital uncompensated care will focus on the estimated coefficient vectors for α2 and α3. If BBA-induced Medicare and Medicaid financial pressure led to reductions in hospital uncompensated care, we expect these coefficients to be negative. We also assess the intervening effects of market conditions on the relationship between our FPI measures and the dependent variables. To do this, we use a set of second-order interactions with the FPI/Year variables in (1). Specifically, we created a dummy variable indicating high overall HMO market share. This was defined as the highest quartile of HMO market share in the 1996 base year of the study.

The remaining variables in (1) reflect the following. Hospital is a vector of hospital organizational characteristics. Market is a vector of market measures that can affect the supply of, or demand for, indigent services in a market. θi is a hospital specific error component, and ɛit represents the random error term. Control variables for Hospital include characteristics likely to affect hospital commitment and capacity to provide indigent care services. Because we did not define safety net hospitals based on ownership, we include a control variable that equaled one for public and church-affiliated hospitals and equaled zero for other nonprofit and for-profit hospitals. We also included controls for a hospital's system and network status given research by Lee, Alexander, and Bazzoli (2003), which suggested that these affiliations could affect hospital involvement in meeting community needs.

Additional hospital variables included the number of high-technology services offered by the hospital, teaching status, and the number of staffed and set up hospital beds. Specifically, our measure for the number of high-technology services was based on Dranove and Shanley (1995) and counts the number of services offered in the following areas: MRI, neonatal intensive care, open heart surgery, cardiac catheterization, and therapeutic radiology. Teaching status equals one if a hospital is a member of the Association of American Medical Colleges Council on Teaching Hospitals, which reflects a major commitment to teaching, and equals zero otherwise. Finally, following Davidoff et al. (2000) we control for the presence of a skilled nursing facility unit because uncompensated care data are aggregated for hospital and skilled nursing units.

The control variables for Market capture factors affecting the demand for indigent care services, market pressures not measured by our FPI measures, and local safety net capacity. Demand for indigent care services is captured through three measures: (1) the percent of the population under age 65 in the market that is uninsured; (2) the percent of children in families with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) who are Medicaid/SCHIP eligible; and (3) the percent of population aged 65 or greater in the market.3 We also included MSA-level hospital HHI and HMO penetration and a state-level measure of the percent of the Medicaid population enrolled in managed care. Measures reflecting the capacity of core safety net providers in a market were also examined, specifically: (1) the ratio of core safety net hospital beds in the market to total population; and (2) the ratio of FQHC visits to total population. Increases in either imply more committed community resources to indigent care.

Analytic Strategy

Our estimation approach takes advantage of the 1996–2000 panel to control for unobserved hospital and market characteristics. We examined two different versions of our basic model: MODEL 1 included the FPI, Hospital, and Market variables but did not include any second-order interactions with high HMO market share variable; and MODEL 2 included the variables noted for MODEL 1 plus the second-order interactions. We estimated these models separately for core, voluntary, and nonsafety net hospital groups.

These uncompensated care models cannot be estimated consistently using ordinary least-squares or random effects because several right-hand side variables are likely to be correlated either with θi or the random error. We conducted specification tests and in all instances found that such correlation exists. As such, fixed effects is preferred over ordinary least squares or random effects because it yields consistent estimates when there is no correlation between the explanatory variables and the random error term. Our fixed effects models utilized approaches that corrected for repeated hospital observations over time, which may affect standard error estimation because of serial correlation in errors.

STUDY FINDINGS

Table 1 provides descriptive data on uncompensated care for the three hospital groups. The 2000 data are adjusted for inflation using the hospital producer price index. Looking first at core safety net hospitals overall, each provided on average $41.5 million in uncompensated care in 1996 and this increased to $50.3 million in inflation-adjusted dollars by 2000. The percent of expenses devoted to uncompensated care for this group was quite high, representing nearly one-fifth of hospital expenses in 1996 and declining slightly by 2000. Voluntary safety net hospitals provided substantially less uncompensated care, an average of $9.9 million in uncompensated care (7.7 percent of expenses) in 1996. Annual costs increased to $12.3 million in 2000 and the percent of expenses uncompensated fell slightly to 7.4 percent. Nonsafety hospitals provided an average of $3.3 million of uncompensated care in 1996, increasing by 20.1 percent to $4.0 million in 2000. The percent of hospital expenses that were uncompensated for the nonsafety group changed from 4.1 to 4.5 percent over the study period.

Table 1.

Average Uncompensated Care Expenses per Hospital by Hospital Safety Net Category: 1996 and 2000

| Annual Uncompensated Care Costs | % of Hospital Expenses Uncompensated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2000* | % Change | 1996 | 2000 | Difference in % | |

| Hospital safety net category | ||||||

| Core safety net hospital | ||||||

| Overall | $41.5 | $50.3 | 21.2% | 19.8% | 18.6% | −1.2 |

| Markets with high HMO market share | 54.6 | 60.7 | 11.1 | 23.2 | 18.5 | −4.7 |

| Markets without high HMO market share | 34.8 | 46.3 | 33.1 | 18.1 | 18.6 | +0.5 |

| Voluntary safety net hospital | ||||||

| Overall | $9.9 | $12.3 | 23.9% | 7.7% | 7.4% | −0.3 |

| Markets with high HMO market share | 11.0 | 11.9 | 8.1 | 5.8 | 5.3 | −0.5 |

| Markets without high HMO market share | 9.6 | 12.5 | 29.7 | 8.3 | 8.2 | −0.1 |

| Nonsafety net hospital | ||||||

| Overall | $3.3 | $4.0 | 20.1% | 4.1% | 4.5% | +0.4 |

| Markets with high HMO market share | 2.6 | 3.1 | 19.8 | 3.5 | 3.6 | +0.1 |

| Markets without high HMO market share | 3.6 | 4.4 | 23.2 | 4.5 | 5.0 | +0.5 |

Values for 2000 are adjusted for inflation to 1996 equivalent dollars using the annual hospital producer price index.

HMO, health maintenance organization.

Table 1 also reports differences in uncompensated care for hospitals in markets with different degrees of HMO market pressure. These data suggest that core and voluntary safety net hospitals had slower real growth in uncompensated care in markets with high HMO market share. In addition, these two hospital groups experienced declines in the percent of their expenses that were uncompensated that were qualitatively large relative to comparably grouped hospitals in markets lacking this private sector payment pressure.

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics on key variables in our analysis. These data represent means across the multiple years, treating each hospital–year combination as a separate observation. The means for log of uncompensated care costs are consistent with the data presented in Table 1. In relation to our key financial pressure policy measures, the negative values for Medicare in each hospital group indicate that Medicare costs in 1997 on average were less than 1998 Medicare revenues despite BBA reductions. Thus, on average, hospitals did not feel great pressure from Medicare in 1998. The results for Medicaid also indicate little pressure on average, especially for core safety net hospitals. Of course, the standard deviations for the fiscal pressure measures are quite large indicating substantial variability in these measures within each hospital group.

Table 2.

Definitions and Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Core Safety Net Hospital | Voluntary Safety Net Hospital | Nonsafety Net Hospital | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Uncompensated care provision | ||||||

| Log of uncompensated care expenses per year | 17.211 | 0.932 | 15.178 | 1.162 | 14.068 | 1.039 |

| Proportion of hospital expenses uncompensated | 0.199 | 0.119 | 0.081 | 0.116 | 0.044 | 0.036 |

| Policy Measures | ||||||

| 1998 Medicare pressure index | −0.013 | 0.063 | −0.010 | 0.077 | −0.008 | 0.084 |

| 1998 Medicaid pressure index | −0.040 | 0.114 | 0.001 | 0.063 | 0.003 | 0.050 |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||||

| Proportion major teaching | 0.433 | 0.496 | 0.337 | 0.473 | 0.066 | 0.248 |

| Hospital bed size | 425.87 | 256.33 | 375.18 | 274.49 | 223.62 | 157.89 |

| Number of hi-tech services offered | 3.306 | 1.635 | 2.983 | 1.954 | 2.238 | 1.631 |

| Proportion with public or religious owner | 0.672 | 0.470 | 0.379 | 0.485 | 0.268 | 0.443 |

| Proportion system members | 0.488 | 0.500 | 0.589 | 0.492 | 0.577 | 0.494 |

| Proportion network members | 0.376 | 0.485 | 0.364 | 0.481 | 0.345 | 0.475 |

| Proportion with skilled nursing unit | 0.274 | 0.446 | 0.293 | 0.455 | 0.398 | 0.490 |

| Market measures | ||||||

| Hirschman–Herfindahl index | 0.204 | 0.133 | 0.225 | 0.158 | 0.206 | 0.157 |

| HMO market share | 0.271 | 0.142 | 0.264 | 0.135 | 0.293 | 0.136 |

| Medicaid HMO market share | 0.452 | 0.264 | 0.470 | 0.273 | 0.488 | 0.265 |

| Ratio of number of core safety net hospital beds in market to population | 0.014 | 0.024 | 0.021 | 0.037 | 0.021 | 0.031 |

| Ratio of number of FQHC visits to population | 0.026 | 0.029 | 0.032 | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.037 |

| Proportion of population under age 65 who are uninsured | 0.200 | 0.072 | 0.178 | 0.073 | 0.173 | 0.074 |

| Proportion of children less than age 17 who are eligible for Medicaid | 0.766 | 0.213 | 0.761 | 0.224 | 0.769 | 0.218 |

| Proportion of population age 65+ | 0.117 | 0.026 | 0.121 | 0.033 | 0.122 | 0.029 |

| N | 376 | 1,049 | 5,572 | |||

HMO, health maintenance organization; FQHC, Federally Qualified Community Health Center.

Table 3 reports our first set of fixed effects results for MODEL 1. Both the analysis of the log of annual uncompensated care expenses and the percent of hospital expenses that were uncompensated are presented. Looking first at core safety net hospitals, we see that the Medicare and Medicaid financial pressure variables are negative in each year, although significant for Medicaid only in 1999 and 2000 and for Medicare only in 1999 for the percent of expenses uncompensated. These findings suggest that Medicaid financial pressure emanating from the initiation of BBA resulted in reductions in uncompensated care, whether measured in annual dollar terms or as a percent of hospital expenses, for core safety net hospitals. These effects were not present for voluntary safety net hospitals or for nonsafety net hospitals. Our findings for Medicaid pressure support hypothesis H1, but only for core safety net institutions. The findings also support H2 for nonsafety net hospitals.

Table 3.

Fixed Effects Regression Models†

| Core Safety Net Hospital | Voluntary Safety Net Hospital | Nonsafety Net Hospital | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Log(UC) | % Expense UC | Log(UC) | % Expense UC | Log(UC) | % Expense UC |

| Policy variables | ||||||

| Medicare pressure, 1998 year | −0.791 | −0.228 | −0.641 | −0.051 | −0.272 | −0.009 |

| Medicare pressure, 1999 year | −0.797 | −0.206* | 0.055 | −0.016 | 0.147 | 0.003 |

| Medicare pressure, 2000 year | −0.344 | −0.209 | 0.129 | 0.292 | 0.188 | 0.016 |

| Medicaid pressure, 1998 year | −0.306 | −0.028 | −0.119 | 0.072 | 0.029 | −0.008 |

| Medicaid pressure, 1999 year | −0.878*** | −0.165** | −0.586 | 0.031 | 0.476 | 0.010 |

| Medicaid pressure, 2000 year | −1.341*** | −0.283*** | −0.993 | 0.111 | −0.107 | −0.025 |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||||

| Hospital beds size (in 00s) | 0.052*** | 0.003 | 0.079*** | −0.005 | 0.063*** | −0.001 |

| Number of hi-tech services | −0.029 | −0.008 | 0.021 | −0.002 | 0.006 | −0.0000 |

| Public or religious owner | 0.259** | 0.028* | 0.051 | 0.010 | 0.039 | 0.007 |

| System member | −0.059 | −0.003 | 0.120 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Network member | −0.057 | −0.010 | −0.067 | −0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Facility has skilled nursing unit | −0.071 | −0.019* | 0.019 | −0.0001 | −0.008 | |

| Market measures | ||||||

| Hirschman–Herfindahl index | 0.004 | −0.028 | −0.547 | −0.079 | 0.345* | 0.043** |

| HMO market share | −0.221 | −0.075* | −0.436*** | −0.051* | 0.085 | 0.007 |

| Proportion of Medicaid population in HMOs | 0.159 | 0.010 | 0.273 | 0.007 | 0.101 | 0.010 |

| Number of core safety net hospital beds | 20.635** | 3.480* | 0.407 | −0.274 | −0.573 | −0.019 |

| Ratio of FQHC visits to population | 2.941 | 0.343 | 1.488 | −0.704 | −2.120*** | −0.087 |

| Proportion of population 65+ | 3.199 | 0.951 | 2.655 | 7.347 | −2.256 | −0.456 |

| Proportion of population under age 65 who are uninsured | 0.902 | 0.155 | −0.013 | 0.138 | 0.090 | 0.028 |

| Proportion of population less than age 17 who are Medicaid eligible | −0.043 | −0.006 | −0.167* | −0.004 | −0.037 | −0.002 |

| Year variables | ||||||

| 1997 | 0.0004 | −019 | 0.082*** | 0.002 | 0.062*** | 0.002* |

| 1998 | −0.059 | 0.003 | 0.115*** | 0.001 | 0.095*** | 0.001 |

| 1999 | 0.088 | −0.017 | 0.178*** | 0.009 | 0.162*** | 0.002 |

| 2000 | 0.111 | −0.001 | 0.237*** | 0.045 | 0.232*** | 0.001 |

| Constant | 16.049*** | 0.027 | 15.038*** | −0.769 | 14.579*** | 0.084*** |

Reported results are from robust regression that accounts for nonindependent distribution of errors in hospital clusters.

p ≤ .10

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01.

HMO, health maintenance organization; FQHC, Federally Qualified Community Health Center.

For core safety net hospitals, only a few other measures in our model are significant. Conversion to public or religious ownership increased annual uncompensated care and had a marginally positive effect on the percent of expenses that were uncompensated. Larger number of hospital beds led to greater annual uncompensated care costs but had no effect on the percent of hospital expenses that were uncompensated. The availability of hospital beds in other core safety net hospitals had a significant positive effect on a given core safety net hospital's uncompensated care provision. This finding is consistent with that of Davidoff et al. (2000) for public hospitals and may represent an unmeasured demand effect in markets with many core safety net hospitals.

For both voluntary safety net hospitals and nonsafety net hospitals, larger size as measured by greater numbers of hospital beds led to more uncompensated care provision but, consistent with core safety net hospitals, had no effect on the percent of a hospital's expenses that were uncompensated. Higher HMO market share is associated with significantly less uncompensated care in voluntary safety net hospitals, both in terms of annual expense and as a percent of hospital expenses. This finding is consistent with Davidoff et al. (2000) and Thorpe et al. (2001). In addition, higher Hirschman–Herfindahl index (HHI), which implies less hospital competition, was associated with more uncompensated care in nonsafety net hospitals. This could occur for reasons suggested by Banks et al. (1997), namely that hospitals in markets with fewer competitors may face greater community expectations for providing uncompensated care. Finally, the FQHC variable has a negative and significant effect on annual uncompensated care provision for nonsafety net hospitals but this was not the case for the other two hospital categories. Because FQHCs provide primary care, greater capacity of FQHCs may allow nonsafety net hospitals to reduce uncompensated primary care in their emergency rooms.

Table 4 focuses exclusively on the fixed effects results from the models that included second-order interactions of the Medicaid and Medicare policy variables with indicators of high HMO market share. These models also included the full set of controls in Table 3.4Table 4 reports the total effects for the Medicare and Medicaid financial pressure measures, which include not only their direct effects but also adds in the relevant interaction effects. We computed standard errors using the variance–covariance matrix for estimated parameters.

Table 4.

| Core Safety Net Hospital | Voluntary Safety Net Hospital | Nonsafety Net Hospital | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Log(UC) | % Expense UC | Log(UC) | % Expense UC | Log(UC) | % Expense UC |

| Markets with high HMO market share | ||||||

| Medicare pressure, 1998 year | −0.579 | −0.138 | −0.041 | 0.062 | −0.338 | −0.010 |

| Medicare pressure, 1999 year | −2.966* | −0.658** | −0.537 | 0.005 | 0.475 | −0.001 |

| Medicare pressure, 2000 year | −0.860 | −0.247 | −0.684 | 0.009 | 0.589* | 0.026*** |

| Medicaid pressure, 1998 year | −0.564 | −0.103 | −1.343*** | −0.081* | −0.179 | 0.012 |

| Medicaid pressure, 1999 year | −0.636** | −0.091 | −2.039*** | −0.114** | 0.684 | 0.054 |

| Medicaid pressure, 2000 year | −1.481*** | −0.284** | −3.141*** | −0.130 | −0.006 | 0.014 |

| Markets without high HMO market share | ||||||

| Medicare pressure, 1998 year | −0.923 | −0.269* | −0.753 | −0.071 | −0.228 | −0.008 |

| Medicare pressure, 1999 year | −0.456 | −0.140 | 0.128 | −0.025 | −0.051 | 0.007 |

| Medicare pressure, 2000 year | −0.159 | −0.196 | 0.291 | 0.349 | −0.046 | 0.011 |

| Medicaid pressure, 1998 year | −0.125 | 0.021 | 0.284 | 0.123* | 0.134 | −0.021 |

| Medicaid pressure, 1999 year | −0.993** | −0.211** | −0.136 | 0.077 | 0.379 | −0.015 |

| Medicaid pressure, 2000 year | −1.226* | −0.283** | −0.171 | 0.209 | −0.111 | −0.045 |

Total effect equals the main effect for a policy variable plus any relevant interaction effect for hospitals in markets with high HMO market share.

Reported results are from robust regression that accounts for nonindependent distribution of errors in hospital clusters.

p ≤ .10

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01.

HMO, health maintenance organization.

Focusing on core safety net hospitals, the results in Table 4 are comparable with those in Table 3. The coefficients on the Medicare and Medicaid financial pressure variables are generally negative in value and many of the Medicaid measures are significant. The Medicaid effects were similar in magnitude regardless of the presence or absence of private sector payer pressure as measured by the high HMO market share indicator. Medicare pressure that resulted from the initiation of BBA was significant in a few instances but the Medicare results lacked much pattern, suggesting at most transitory effects. However, the effect of Medicaid pressure was sustained over time and appears to have grown through 2000 for both annual uncompensated care provision and for the percent of expenses uncompensated.

Unlike core safety net hospitals, the effect of BBA-induced financial pressure on voluntary safety net hospitals appears to depend on private sector market pressures. In high HMO market share markets, we observe sharp reductions in annual uncompensated care provision among voluntary safety net hospitals as BBA-induced Medicaid pressure increased. These effects are very large in magnitude, and in fact, exceed those observed for core safety net hospitals. More specifically, when we estimated a model for the log of uncompensated care that combined the voluntary and core safety net samples and interacted the policy measures with voluntary safety net hospital status, the relevant Medicaid interactions were all significant at the p < .05 level. The results for the percent of hospital expenses that were uncompensated also indicated reductions in uncompensated care for voluntary safety net hospitals but, qualitatively, these results were more similar in magnitude to core safety net hospitals. This suggests that Medicaid pressure may be motivating voluntary safety net hospitals in high HMO penetration markets not only to reduce annual uncompensated care provision but also to shed overall hospital costs to deal with mounting payment pressure. The strong responses to Medicaid pressure were not present when we examined voluntary safety net hospitals in markets without high HMO market share. Thus, it appears that for hospitals in the voluntary safety net sector, it is the combined impact of private sector payer pressures and declining Medicaid revenues that precipitate hospital reductions in uncompensated care. Thus, our hypothesis H3 appears to be supported strictly for voluntary safety net hospitals. Finally, the results for nonsafety net hospitals are largely consistent with Table 3. Namely, we do not observe substantial effects of the policy variables on uncompensated care provision for these hospitals. The positive effects for Medicare pressure in 2000 provides some support for our hypothesis H2. But the findings lack any time pattern of growing or lessening effect as we saw for the other hospital categories. In addition, as noted earlier, this positive effect might reflect measurement bias given the use of cost and revenue data to construct the dependent variable and the FPI measures.

DISCUSSION

The BBA of 1997 initiated several changes to Medicare and Medicaid payment policy. Our empirical results suggest that Medicaid pressure that resulted from the initiation of BBA affected uncompensated care provision in safety net hospitals that are core to indigent health care delivery in their communities. In addition, voluntary safety net hospitals, which provide less uncompensated care than core institutions but are still important providers of this care, cut back on uncompensated care when faced with the combined forces of Medicaid payment declines and private sector payment pressures. The Medicare payment changes initiated by BBA had more limited, and possibly only transitory, effects on uncompensated care provision for core and voluntary safety net hospitals.

These results, and additionally the lack of a payment effect on nonsafety net hospitals, are all consistent with economic theories of hospital behavior. In particular, Hoerger (1991) suggested that utility maximizing hospital would eschew high profits in munificent periods in favor of expanding the quality of care and providing charity care to the uninsured. Conversely, when times are tough because of payment cuts, these hospitals reduced these activities, and thus, we are likely to see declines in uncompensated care so that hospitals can reach their profit targets. Profit maximizing hospitals, on the other hand, are already cost minimizing in terms of providing an acceptable quality of care and meeting community expectations to provide indigent care. Thus, payment changes should have little effect on these dimensions for these institutions.

There are, however, important limitations of our analysis that must be noted. First, because we used actual uncompensated care provision to identify safety net hospitals to avoid the deficiencies associated with using ownership or teaching status, regression to the mean may bias our findings. We used lagged uncompensated care data to reduce these effects but this does not eliminate all potential regression to the mean. However, if regression to the mean was a major factor in our analysis, it should be apparent for both core and voluntary safety net hospitals and should not depend on the presence or absence of high HMO market share. A second limitation is that due to the vagaries of hospital accounting practices, we are unable to assess whether financial pressure is limiting ex ante decisions of hospitals to provide charity care versus the ex post decision to write off unpaid bills as bad debt. Growing financial pressures may cause hospitals to be more aggressive in collecting unpaid bills rather than reduce ex ante free care. However, if hospitals are more aggressive in this regard, they are less forgiving to patients who are having troubles paying their bills. As such, both potential hospital actions may have the same effect on medically indigent individuals who have limited means to afford their care.

Finally, it is important to note that our study strictly examines the initial effects of BBA implementation on hospital uncompensated care decisions. Certainly, initial BBA provisions did have a large impact on hospital payments, especially the freeze on Medicare DRG payments and Medicaid DSH payments in 1998. However, additional provisions took affect in later years, some of which are related to initial BBA provisions (e.g., the transition in reductions for Medicare DSH and indirect medical education payments) but others of which are unrelated (e.g., implementation of Medicare prospective payment systems for skilled nursing facilities in 1999 and outpatient care in 2000). Nevertheless, our results suggest that initial provisions of BBA were large enough to create cuts in uncompensated care delivery among safety net hospitals.

Our findings raise two important policy concerns that are of immediate importance given actions under consideration by the states and the federal government to deal with continuing budget problems. The first relates to the susceptibility of core safety net hospitals to payment pressures, especially those associated with Medicaid. As we have defined them, core safety net hospitals play an integral role in indigent care in their communities. These institutions have both large market shares of uncompensated care and large portions of their hospital expenses that are uncompensated. Thus, the indigent care cutbacks these institutions make when faced with Medicaid financial pressure likely have a large impact on many people in their communities.

A second policy concern is that core safety net hospitals are highly dependent on Medicaid revenues, with about 30 percent of their inpatient days covered by this payer (Bazzoli et al. 2005). This raises concern in light of recent legislation passed by the U.S. Congress to trim $10 billion from Medicaid over the 4 years beginning in 2007 (Loos 2005). Given the strain that Medicaid is placing on state budgets, state governments are unlikely to fill this funding gap. The next step to identifying Medicaid reductions is the establishment of a commission to identify “… areas of fraud and abuse in the state-reimbursement component of Medicaid” (Loos 2005, p. 6). Given the tainted history of Medicaid DSH in terms of state optimization strategies, it likely will be a major target for discussion and potential cuts as it was under BBA. Our findings suggest this could have a detrimental effect on the U.S. safety net.

Overall our findings suggest that concerns raised in the 2000 IOM report on the safety net were quite real and remain important given current policy directions. The hospital safety net remains fragile and it may be adversely affected by policy changes that will arise in the next few years.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Health Care Financing and Organization Program (# 042596). The authors thank participants in the 2003 Southeastern Health Economics Group for their thoughtful comments on the paper. In addition, we appreciate the assistance of Anthony T. LoSasso in obtaining data on rates of uninsured and percent of children eligible for Medicaid in different communities. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 2003 International Health Economics Association meetings and the 2004 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meetings. The authors also thank the editor and our reviewers for many thoughtful and helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

NOTES

In particular, if 1996 uncompensated care was unusually high for certain hospitals and we used these data to identify safety net hospitals, these institutions would likely experience a sharp decline in uncompensated care to more typical levels and this effect may be attributed mistakenly to BBA. Regression to the mean may take a number of years to resolve but the largest adjustment back to the norm likely occurs immediately after an unusually high value, with smaller adjustments in subsequent periods.

The AHA calculates adjusted admissions each year. Basically, the measure translates outpatient visits into inpatient admission equivalents based on the relative revenue generated by an outpatient visit vis-à-vis an inpatient admission. We estimated Medicare adjusted admissions by multiplying AHA calculated adjusted admissions by the percentage of a hospital's gross revenues associated with Medicare patients.

The data on uninsured were derived from the March Current Population Survey. MSAs for which this proportion could not be constructed because of insufficient data were assigned the mean value of the variable so that they would not affect the estimated coefficient. The percent of children that were Medicaid/SCHIP eligible was also derived from the Current Population Survey through a simulation that took into account household income and the specific rules by year for Medicaid/SCHIP in different states.

Results for these other control variables differed minimally. The full set of results from this estimation is available from the lead author on request.

References

- Atkinson G, Helms W D, Needleman J. State Trends in Hospital Uncompensated Care. Health Affairs. 1997;16(4):233–41. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks D, Paterson A M, Wendel J. Uncompensated Hospital Care: Charitable Mission or Profitable Business Decision? Health Economics. 1997;6(2):133–43. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199703)6:2<133::aid-hec252>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoli G J, Kang R, Hasnain-Wynia R, Lindrooth R C. An Update on the Safety-Net Hospitals: Coping with the Late 1990s and Early 2000s. Health Affairs. 2005;24:1047–56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E S, Ahern M W. Have Procompetitive Changes Altered Hospital Provision of Indigent Care? Health Economics. 1993;2:281–9. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730020311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham P, Tu H T. A Changing Picture of Uncompensated Care. Health Affairs. 1997;16(4):167–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff A J, LoSasso A T, Bazzoli G J, Zuckerman Z. The Effect of Changing State Health Policy on Hospital Uncompensated Care. Inquiry. 2000;37:253–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranove D, Shanley M. Cost Reductions or Reputation Enhancement as Motives for Mergers: The Logic of Multi-Hospital Systems. Strategic Management Journal. 1995;16(1):55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Frank R G, Salkever D S. The Supply of Charity Services by Nonprofit Hospitals: Motives and Market Structure. Rand Journal of Economics. 1991;22(3):430–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin D. Altruism or Moral Hazard: The Impact of Hospital Uncompensated Care Pools. Journal of Health Economics. 1997;16:397–416. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(96)00539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterman S. Putting Medicare into Context: How Does the Balanced Budget Act Affect Hospitals? 2000. Paper Commissioned by the National Health Policy Forum, July 2000.

- Hadley J, Holohan J. How Much Medical Care Do the Uninsured Use, and Who Pays for It? Health Affairs. 2003. [May 6, 2005]. Web Exclusive February 12, 2003, W3-66. Available at http://content.healthaffairs.org/webexclusives/index.dtl?year=2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hadley J, Zuckerman S, Feder J. Profits and Fiscal Pressure in the Prospective Payment System: Their Impacts on Hospitals. Inquiry. 1989;26:354–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger T J. ‘Profit’ Variability in For-Profit and Not-For-Profit Hospitals. Journal of Health Economics. 1991;10:259–89. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90030-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S D, Alexander J A, Bazzoli G J. Who Do They Serve? Community Responsiveness among Hospitals Affiliated with Health Systems and Networks. Medical Care. 2003;41:165–79. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000039838.13313.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin M E, Altman S. America's Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered. 2000. A Report of the Committee on the Changing Market, Managed Care, and the Future Viability of Safety Net Providers, Institute of Medicine Summary Prepublication Report. [PubMed]

- Loos R. The Fix Is in for Medicaid: With $10 Billion in Medicaid Spending Reductions Approved by Congress, The Next Battle Is over Forming the Commission. Modern Healthcare. 2005;6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann J M, Melnick G A, Bamezai A, Zwanziger J. A Profile of Uncompensated Hospital Care. Health Affairs. 1997;16:27–54. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Prospective Payment Assessment Commission. A Data Book: Healthcare Spending and the Medicare Program, Chapter 7. Washington, DC: MedPac; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Melnick G A, Mann J M, Bamezai A. Preliminary Findings: Hospital Uncompensated Care Not Keeping Pace with Per Capita Spending. HCFO News and Progress. 2000 March 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum S, Darnell J. A Comparison of the Medicaid Provisions in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-33) with Prior Law. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rosko M D. The Provision of Uncompensated Care: Motivation and Threshold Effects. Health Care Management Review. 2004;29:229–39. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe K E, Seiber E E, Florence C S. The Impact of HMOs on Hospital-Based Uncompensated Care. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law. 2001;26:543–55. doi: 10.1215/03616878-26-3-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman S, Bazzoli G, Davidoff A, LoSasso A. How Did Safety Net Hospitals Cope in the 1990s? Health Affairs. 2001;20:159–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwanziger J, Melnick G A. The Effects of Hospital Competition and the Medicare PPS Program on Hospital Cost Behavior in California. Journal of Health Economics. 1988;7:301–20. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(88)90018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwanziger J, Melnick G A, Bamezai A. The Effect of Selective Contracting on Hospital Costs and Revenues. Health Services Research. 2000;35:849–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]