Abstract

Bacillus subtilis can use methionine as the sole sulfur source, indicating an efficient conversion of methionine to cysteine. To characterize this pathway, the enzymatic activities of CysK, YrhA and YrhB purified in Escherichia coli were tested. Both CysK and YrhA have an O-acetylserine-thiol-lyase activity, but YrhA was 75-fold less active than CysK. An atypical cystathionine β-synthase activity using O-acetylserine and homocysteine as substrates was observed for YrhA but not for CysK. The YrhB protein had both cystathionine lyase and homocysteine γ-lyase activities in vitro. Due to their activity, we propose that YrhA and YrhB should be renamed MccA and MccB for methionine-to-cysteine conversion. Mutants inactivated for cysK or yrhB grew similarly to the wild-type strain in the presence of methionine. In contrast, the growth of an ΔyrhA mutant or a luxS mutant, inactivated for the S-ribosyl-homocysteinase step of the S-adenosylmethionine recycling pathway, was strongly reduced with methionine, whereas a ΔyrhA ΔcysK or cysE mutant did not grow at all under the same conditions. The yrhB and yrhA genes form an operon together with yrrT, mtnN, and yrhC. The expression of the yrrT operon was repressed in the presence of sulfate or cysteine. Both purified CysK and CymR, the global repressor of cysteine metabolism, were required to observe the formation of a protein-DNA complex with the yrrT promoter region in gel-shift experiments. The addition of O-acetyl-serine prevented the formation of this protein-DNA complex.

Methionine plays a central role in a variety of cellular functions. This amino acid is the universal initiator of protein synthesis, and its derivative, S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet), is involved in several cellular processes, including methylation and polyamine biosynthesis. Methionine synthesis and degradation are, therefore, tightly regulated.

Bacillus subtilis, like several microorganisms (21, 28, 55), can use sulfate for the synthesis of organic sulfur metabolites, mostly cysteine, methionine, and AdoMet. As in enterobacteria (28), the sulfate assimilation pathway of B. subtilis involves uptake and activation of inorganic sulfate, followed by stepwise reduction to sulfide (Fig. 1) (9, 23, 34, 59). An O-acetylserine-thiol-lyase, the cysK gene product, catalyzes the reaction of sulfide and O-acetylserine (OAS) to give cysteine (59). Cysteine is then converted into homocysteine by the transsulfuration pathway, which requires the sequential action of a cystathionine β-synthase, MetI, and two cystathionine β-lyases, MetC and PatB (6, 7). Homocysteine is subsequently methylated to methionine by a sole B12-independent methionine synthase encoded by the metE gene (5) (Fig. 1).

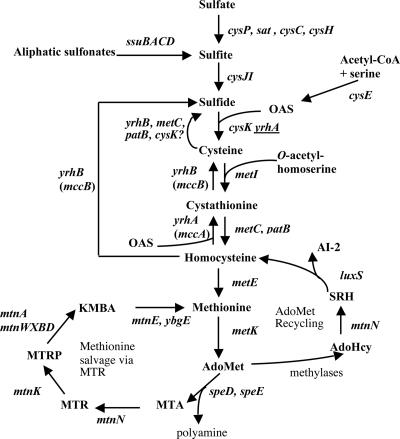

FIG. 1.

Biosynthesis and recycling pathways of sulfur containing amino acids. The enzymes present in B. subtilis are indicated by the corresponding genes: cysP, sulfate permease; sat, ATP sulfurylase; cysC, APS kinase; cysH, APS-PAPS reductase; ssuBACD, aliphatic sulfonates uptake and degradation; cysJI, sulfite reductase; cysE, serine O-acetyltransferase; cysK, OAS thiol-lyase; YrhB, MetC, PatB, and CysK have cysteine desulfhydrase activity in vitro; metI, cystathionine γ-synthase; metC and patB, cystathionine β-lyases; metE, methionine synthase; metK, AdoMet synthetase; speD, AdoMet decarboxylase; speE, spermidine synthase; mtnN, AdoHcy/MTA nucleosidase; mtnK, methylthioribose kinase, mtnA and mtnWXBD genes products are involved in the MTR-to-KMBA recycling pathway; mtnE, aminotransferase; luxS, S-ribosylhomocysteine hydrolase; yrhA (mccA), cystathionine β-synthase; yrhB (mccB), cystathionine γ-lyase and homocysteine γ-lyase. The presence of underlined yrhA indicates low OAS thiol-lyase activity in vitro for YrhA. APS, adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate; KMBA, α-keto-γ-methyl-thiobutyric acid; MTA, methylthioadenosine; MTR, methylthioribose; PAPS, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate; SRH, S-ribosylhomocysteine.

AdoMet is synthesized from methionine and ATP by an AdoMet synthase encoded by the metK gene (21, 66). Utilization of AdoMet as a methyl donor results in formation of S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoHcy). AdoHcy is converted to homocysteine in two steps catalyzed by the mtnN and luxS gene products, respectively (44, 49) (Fig. 1). AdoMet is also the precursor of polyamines leading to the production of methylthioadenosine (MTA). MTA is degraded in adenine and methylthioribose (MTR) by MTA nucleosidase, MtnN. The major subsequent steps for MTR recycling in B. subtilis have been recently characterized (4, 50).

B. subtilis can also use methionine as sole sulfur source. Microorganisms and mammals catabolize l-methionine by three main pathways (51). Methionine can be directly converted to methanethiol, α-ketobutyrate, and ammonium by a methionine γ-lyase (EC 4.4.1.11), an enzyme that is found in many bacteria (2, 25, 31, 54). Methionine utilization can also occur via a two-step degradation pathway initiated by an aminotransferase (67, 68). This enzyme requires the presence of an acceptor, e.g., α-ketoglutarate, to give α-keto-γ-methyl-thiobutyric acid (KMBA), which is subsequently degraded to methanethiol (10). In Klebsiella aerogenes and Pseudomonas putida, methanethiol may be oxidized to sulfite via a methanesulfonate intermediate (48, 61). The third pathway involves the conversion of methionine to homocysteine through AdoMet and then the reverse transsulfuration pathway, which converts homocysteine to cysteine via the intermediary formation of cystathionine (Fig. 1). The reverse transsulfuration pathway, present in mammals, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, requires the sequential action of cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionine γ-lyase (55, 61).

A number of enzymes involved in the metabolism of cysteine, homocysteine, and methionine are evolutionary related. Cystathionine γ-synthase, cystathionine β-lyase, cystathionine γ-lyase, O-acetylhomoserine thiol-lyase, and methionine γ-lyase constitute a protein family, whereas OAS thiol-lyase and cystathionine β-synthase form a second family (35). The YrhB and YrhA proteins of B. subtilis belong to the cystathionine γ-synthase and to the OAS thiol-lyase family of proteins, respectively. They are good candidates to participate in the conversion of methionine to cysteine via the reverse transsulfuration pathway. We have previously shown that the expression of yrhA and yrhB genes is increased in the presence of methionine compared to the presence of sulfate (5). In addition, the expression of these genes is controlled by CymR, the central repressor of cysteine metabolism, and by CysK, the OAS thiol-lyase (1, 18). A CymR-dependent binding to the yrrT promoter region has been observed using crude extracts of Escherichia coli DH5α overproducing CymR, and OAS prevents the binding of this repressor (18). In the present study, the possible involvement of YrhA and YrhB in the utilization of methionine as the sole sulfur source in B. subtilis was analyzed. The signaling pathway, which modulates the CymR-dependent repression of yrhA and yrhB, was also studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The B. subtilis strains used in the present study are listed in Table 1. A wild-type E. coli FB8 strain was used in the present study (11), as well as an NK3 mutant (ΔtrpE5 leu-6 thi hsdR hsdM+ cysK cysM), which is a cysteine auxotroph (24). E. coli cells were grown in LB broth (45) in M63 medium (100 mM KH2PO4, 40 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM FeCl3, 0.5% glucose, and 15 μM vitamin B1) or in a sulfur-free M63 medium (100 mM KH2PO4, 40 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM FeCl3, 0.5% glucose, and 15 μM vitamin B1). B. subtilis was grown in SP medium or in minimal medium (6 mM K2HPO4, 4.4 mM KH2PO4, 0.3 mM trisodium citrate, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 μM CaCl2, 5 μM MnCl2, 0.5% glucose, 50 mg of l-tryptophan liter−1, 22 mg of ferric ammonium citrate liter−1, 0.1% l-glutamine, 20 mM xylose) supplemented with a sulfur source as stated: 0.2 or 1 mM K2SO4, 0.2 or 1 mM l-methionine, 0.1 or 0.25 mM l-cystine, 0.05 or 0.5 mM l-cysteine, 0.2 or 1 mM dl-homocysteine, and 0.2 or 1 mM dl-cystathionine. For the BFS2063 and BSIP1870 mutants, 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added, allowing the expression of genes downstream from yrhA under the control of the Pspac promoter. When required, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 5 μg ml−1; spectinomycin, 100 μg ml−1; and kanamycin 5 μg ml−1. Solid media were prepared by the addition of 20 g of Noble agar (Difco) liter−1. Standard procedures were used to transform E. coli and B. subtilis (29, 45). The loss of amylase activity was detected as previously described (53).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this studya

| B. subtilis strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | Laboratory stock |

| BSIP1144 | trpC2 amyE::pΔA(−108, +126) yrrT′-lacZ cat | 18 |

| BSIP1165 | trpC2 yrhB::aphA3 | pDIA5533 → 168 |

| BSIP1303 | trpC2 ΔyrhAB::aphA3 | This study |

| BSIP1304 | trpC2 ΔcysK::spc | 6 |

| BSIP1305 | trpC2 ΔyrhAB::aphA3 ΔcysK::spc | BSIP1304 → BSIP1303 |

| BSIP1314 | trpC2 amyE::(pΔAyrrT′-lacZ) ΔcysK::spc | BSIP1304 → BSIP1144 |

| BSIP1758 | trpC2 ΔluxS::cat | This study |

| BSIP1794 | trpC2 amyE::(pΔA yrrT′-lacZ cat) ΔcymR | 18 |

| BSIP1837 | trpC2 purA26 cysE14 amyE::(pΔA yrrT′-lacZ cat) | pDIA5512 → QB944 |

| BSIP1840 | trpC2 purA26 cysE14 ΔcysK::spc amyE::(pΔA yrrT′-lacZ cat) | DNA BSIP1304 → BSIP1837 |

| BSIP1870 | trpC2 yrhA′::lacZ-erm ΔyrhA ΔcysK::spc | DNA BSIP1304 → BFS2063 |

| BFS2063 | trpC2 yrhA′::lacZ-erm ΔyrhA | W. Schumann (27) |

| QB944 | trpC2 purA26 cysE14 | 17 |

Arrows indicate construction by transformation. cat is the pC194 chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene, aphA3 is a kanamycin resistance gene, spc is a spectinomycin resistance gene, and erm is the pMutin erythromycin resistance gene. BFS2063 was constructed during the Bacillus Functional Analysis Program using the pMutin4 system (27).

Plasmid and strain construction.

Plasmids from E. coli and chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis were prepared according to standard procedures. Restriction enzymes, DNA polymerase, and phage T4 DNA ligase were used as recommended by the manufacturers. DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels with the QiaQuick kit (QIAGEN, Basel, Switzerland). DNA sequences were determined by using the dideoxy-chain termination method with plasmid DNA as a template and the Thermo Sequenase kit (USB Corporation).

The coding sequence of yrhB (nucleotides −56 relative to the translational start point to +87 relative to the translational stop site) was amplified by PCR using primers containing a 5′-BamHI site or a 3′-EcoRI site. This fragment was inserted between the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pHT315 (3), resulting in plasmid pDIA5532. A ClaI-restricted kanamycin resistance cassette was cloned into the BstBI site of pDIA5532, resulting in pDIA5533. This plasmid was linearized by ScaI and used to transform B. subtilis 168. The yrhB gene was disrupted by the kanamycin resistance cassette by a double-crossover event to give strain BSIP1165 (Table 1).

To obtain strain BSIP1303, in which the yrhA and yrhB were deleted and replaced by a kanamycin resistance cassette (aphA3), a four-primer PCR procedure was used (62). The regions upstream from yrhA gene (nucleotides −961 to −61 relative to the yrhA translational start site) and downstream from yrhB (nucleotides −142 to +857 relative to the yrhB translational stop site) were amplified by PCR, so that 21-bp fragments corresponding to the aphA3 gene were introduced at one of their ends. The yrhA upstream and yrhB downstream regions overlapping the aphA3 gene at one of their ends then served as long primers for PCR using aphA3 as a template. In this second PCR, two external primers were added. The final product, corresponding to the region upstream of yrhA and downstream of yrhB with the inserted aphA3 cassette in-between, was purified from a gel and used to transform B. subtilis 168 giving strain BSIP1305 (Table 1).

The luxS gene was replaced by a chloramphenicol resistance cassette using the same four-primer PCR procedure. The regions upstream and downstream from luxS (nucleotides −801 to +15 and +420 to +1350 relative to the translational start site) were amplified by PCR so that 21-bp fragments corresponding to the cat gene were introduced at one of their ends. The luxS upstream and downstream regions overlapping the cat gene at one of their ends then served as long primers for PCR using cat as a template. The final product was used to transform B. subtilis 168, yielding strain BSIP1758 (Table 1).

RNA isolation and analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from B. subtilis 168 grown in minimal medium with 1 mM sulfate or 1 mM methionine. Exponentially growing cells were harvested at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 by centrifugation for 2 min at 4°C. One gram of 0.1-mm-diameter glass beads (Sigma) was added. The cells were broken by shaking in a Fastprep apparatus (Bio 101) twice for 30 s each time. Total RNA was extracted as previously described (23).

For Northern blot analysis, 3 μg of total RNA was separated in a 1.5% denaturing agarose gel containing 2% formaldehyde and transferred to Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham). The digoxigenin-labeled probe was generated with a DIG labeling kit (Roche). The probe consisted of a 660-bp fragment corresponding to nucleotides +223 to +883 relative to the translational start site of yrhB. The membranes were hybridized at 45°C in hybridization solution containing 50% formamide, 5× Denhardt's reagent, 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 200 μg of sheared salmon sperm DNA ml−1. The size of the transcript was determined by comparison with RNA molecular weight standards (Gibco-BRL). For the primer extension experiment, the primer IV61 5′-TCACGGCCCATATTTGTCACACTCCATATTTAA-3′ was labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and hybridized with 10 μg of RNA. The DNA primer was extended by use of reverse transcriptase, and the products were analyzed as previously described (45). The same primer was used to generate a sequence ladder according to the method of Sanger.

Overproduction and purification of YrhB, YrhA, CysK and CymR.

The yrhA gene (nucleotides 1 to 921 relative to the translational start site), the yrhB gene (nucleotides 1 to 1137 relative to the translational start site), and the cysK gene (nucleotides 1 to 924 relative to the translational start site) were amplified by PCR using primers introducing a 5′-NdeI and a 3′-XhoI site and were cloned in the pET22b+ vector (Novagen) digested by NdeI and XhoI. The stop codon of these genes was replaced by a XhoI restriction site. This allows the creation of a translational fusion adding six carboxy-terminal histidine residues. The expression of the yrhA, yrhB, or cysK gene was placed under the control of the T7 promoter. The CymR protein was purified by using the intein-chitin binding domain (CBD) system (New England Biolabs). The cymR (yrzC) gene (nucleotides 1 to 422 relative to the translation start site) was amplified by PCR and cloned in the pTYB11 vector to form a translational fusion CymR-intein-CBD. The plasmids pDIA5686 (pET22b+yrhA), pDIA5695 (pET22b+yrhB), pDIA5708 (pET22b+cysK), or pDIA5770 (pTYB11cymR) were transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain (Novagen), which contains pDIA17 (38) encoding the LacI repressor. The resulting strains were grown at room temperature in LB medium to an OD600 of 1.5, and IPTG (1 mM) was added to induce the expression of yrhB, cysK, or cymR, followed by incubation for 3 h. In the case of yrhA overexpression, 0.1 mM IPTG was used for induction. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8) and 300 mM NaCl. E. coli crude extracts were loaded on a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column. The YrhAHis6, YrhBHis6, and CysKHis6 proteins were eluted in the presence of 300 mM imidazole. E. coli crude extracts containing the CymR-intein-CBD protein fusion were loaded on a chitin column. The CymR protein was eluted after the cleavage of intein in the presence of 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The purified CymR was concentrated, and DTT was eliminated by using an Amicon Ultra column (UFCB801024). The purification of YrhAHis6, YrhBHis6, CysKHis6, and CymR was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

Enzyme assays.

β-Galactosidase specific activity was measured as described by Miller (36) with cell extracts obtained by lysozyme treatment. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford. One unit of β-galactosidase is defined as the amount of enzyme that produces 1 nmol of O-nitrophenol (ONP) min−1 at 28°C. The mean value of at least three independent experiments is presented. The standard deviations are <15%.

OAS thiol-lyase catalyzes the reaction of O-acetylserine and sulfide to give cysteine. The production of cysteine was tested with the ninhydrin method described by Gaitonde (20) and adapted by Ravanel et al. (42). The reaction mixture contained 100 mM phosphate (pH 7.5), 20 μM pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), 10 mM OAS, 10 mM Na2S, and various amounts of purified CysKHis6 or YrhAHis6 in a final volume of 1 ml. The reaction mixture was incubated for 2 to 10 min at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 300 μl of the acid ninhydrin reagent. Samples were heated for 10 min at 100°C, cooled for 2 min on ice, and kept at room temperature. Then, 650 μl of 95% ethanol was added, and the absorbance at 560 nm of the sample was determined. The amount of cysteine produced is calculated from a calibration curve, which shows a linear relation between absorbance and concentrations up to 2 mM cysteine.

Cystathionine β-synthase catalyzes the reaction of l-homocysteine and serine or serine derivatives to give cystathionine. This compound displays a peak of absorption at 455 nm in the presence of ninhydrin in acid solution as described by Kashiwamata and Greenberg (26). The reaction mixture contained 100 mM phosphate (pH 7.5), 20 μM PLP, 10 mM homocysteine, 10 mM OAS, or 10 mM serine and various amounts of enzyme. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C. Samples were taken at regular intervals, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of the acid ninhydrin solution. After 5 min at 100°C, samples were cooled at room temperature, and the absorbance at 455 nm was determined. The amount of cystathionine produced was calculated from a calibration curve, which shows a linear relation between absorbance and concentration up to 20 mM cystathionine.

The OAS thiol-lyase and cystathionine β-synthase activity was also estimated spectrophotometrically at 340 nm by following the amount of acetate released from OAS, in a coupling system that involved acetate kinase, pyruvate kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase and NADH as indicator. The reaction mixture (0.5 ml final volume) contained the following reagents: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 μM PLP, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, 0.5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.15 mM NADH, 1 mM OAS, 20 U of acetate kinase, 3 U of each pyruvate kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase. The samples were equilibrated for several minutes at 30°C, and then the reaction was started by adding appropriate amounts of enzyme and either 1 mM Na2S or 2 mM homocysteine. The decrease in absorption at 340 nm was monitored for 5 min, the linear segment being used to calculate the specific activity.

Cystathionine γ-lyase catalyzes the conversion of cystathionine to ammonia, α-ketobutyrate, and cysteine. The production of free thiol groups was measured by spontaneous disulfide interchange with 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) (57). The reaction mixture contained 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 0.2 mM DTNB, 20 μM PLP, various cystathionine concentrations (200 μM to 10 mM), and 10 μg of purified YrhB. The increase in absorbance at 412 nm was measured at intervals of 0.5 min for 20 min. A molar absorption coefficient for the aryl mercaptide of 13,400 M−1 cm−1 was used to calculate the enzyme activity. One enzyme unit represents the formation of 1 μmol of arylmercaptan min−1 at 30°C. Methionine γ-lyase activity leading to the production of methanethiol was also measured with DTNB using methionine instead of cystathionine as a substrate.

Homocysteine γ-lyase was assayed as described by Thong and Coombs (56). The reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 μM PLP, 3 mM l-homocysteine, 0.33 mM lead acetate, and 10 μg of purified YrhB in a final volume of 1 ml. The release of H2S at 37°C was detected by using lead acetate as a trapping agent, and PbS production was monitored at 360 nm. The amount of H2S produced was calculated from a calibration curve showing a linear relation between absorbances and concentrations of Na2S up to 150 μM.

Sulfur containing products were identified by using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) as follows. The enzymatic activity was assayed as indicated for each enzyme in the presence of 10 or 50 μg of the corresponding purified protein. The reaction was stopped after 15 or 30 min of incubation at 30°C by the addition of sulfosalicylic acid (final concentration, 3%). Samples of the supernatant obtained after centrifugation were analyzed by ion-exchange chromatography, followed by ninhydrin post-column derivatization (22). A PCX5200 post-column derivatizer (Pickering Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) was connected to a Waters 626 HPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA). Amino acids were separated on a lithium ion-exchange column (3 mm [inner diameter] by 150 mm; Pickering) and detected at 570 and 440 nm on a Waters 2487 dual absorbance detector (22).

Volatile molecules were extracted by solid-phase microextraction (SPME) and analyzed by using a system composed of a gas chromatograph (GC6890+; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) connected to a mass spectrometer detector (MS5973N; Agilent Technologies). Briefly, volatile molecules were extracted by plunging a 75-μm Carboxen PDMS fiber (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA) into the headspace of the reacting vial at 37°C for 15 min and were thermally desorbed from the fiber at 240°C in the splitless injector. Molecules were separated by using a HP Innowax capillary column (60 m by 0.25 mm, 0.50-μm film thickness) (Agilent Technologies) flushed with high-purity helium at a constant flow of 1.4 ml min−1. The temperature was increased from 40 to 240°C with a linear gradient of 10°C min−1. The column was directly connected to the mass detector in scan mode (electronic impact energy = 70 eV, m/z range = 20 to 200). H2S was identified by its retention time and comparison of its spectrum with those of NIST 98 library (National Institute of Standards and Technology) and quantified by external standard calibration (12).

The bioluminescence assay for the detection of autoinducer 2 (AI-2) was performed as follows. B. subtilis strains were grown at 37°C in minimal medium with 1 mM homocysteine until the late exponential phase. Cells were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm, and the supernatants were filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter. This cell-free conditioned culture medium was kept at −20°C. Vibrio harveyi indicator strain BB 170 (8) was grown overnight at 30°C in autoinducer bioassay medium and then diluted 1:10,000 in fresh autoinducer bioassay broth, with 10% cell-free conditioned culture medium. Aliquots (1 ml) were taken hourly during 4 h to measure the bioluminescence using a Lumat 9507 luminometer (Berthold).

Growth of the cysteine auxotroph E. coli NK3 with various sulfur sources.

A total of 13.5 μg of purified YrhB was incubated for 5 min at 37°C in 2 ml of a reaction mixture composed of 6 mM l-cystathionine, 20 μM PLP, and 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). The reaction was stopped by heating it for 2 min at 100°C, and the sample was sterilized by filtration. A cysK cysM mutant, NK3, was grown overnight in M63 minimal medium supplemented with 1 mM leucine, 50 mg of tryptophan liter−1, and 100 μM l-cystine. NK3 cells were washed three times in M63, and 10 μl of the cells was distributed in a 12-well microtitration plate. Then, 100 μM l-cystine, 200 μM cystathionine, 200 μM homocysteine, or 65 μl of the reaction mixture was added. The OD600 was determined after 24 h of growth at 37°C.

Gel mobility shift assays.

A PCR fragment containing the pΔA(−108, +126) yrrT promoter region was amplified using the primers IV48 (5′-GGGAATTCATATGAAGTATAAGCTTTTTTGC-3′) and IV37 (5′-GGGGGATCCTTGTACTGTTTGATCATAAG-3′) and pDIA5512 carrying the pΔAyrrT′-lacZ fusion as a template (18). This PCR product was labeled by using [γ-32P]ATP 5′-end-labeled specific primer IV48. Unincorporated oligonucleotides were removed by using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). Protein-DNA complexes were formed in 10-μl volumes by incubating the 32P-end-labeled DNA fragment with different amounts of purified CymR and CysK or with crude extracts of E. coli NK3 carrying either pDIA5735 (pXT-pxylA-yrzC) or pXT (negative control) (18). The DNA-binding assays were performed in 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7)-150 mM NaCl-0.1 mM EDTA-2 mM MgSO4-1 mM DTT-10% glycerol in the presence of 0.1 μg of poly(dI-dC) ml−1 as previously described (13). When specified, OAS or NAS (Sigma) was added to the reaction mixture at different concentrations.

RESULTS

Role of LuxS in AI-2 production and in the conversion of methionine to homocysteine.

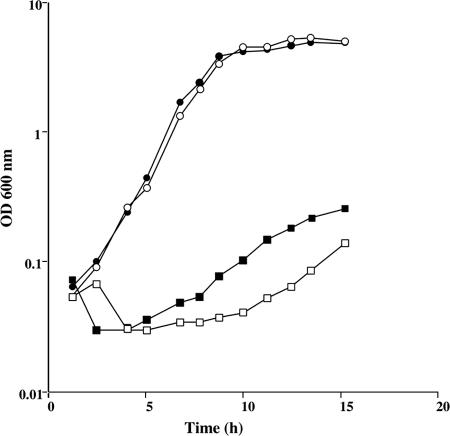

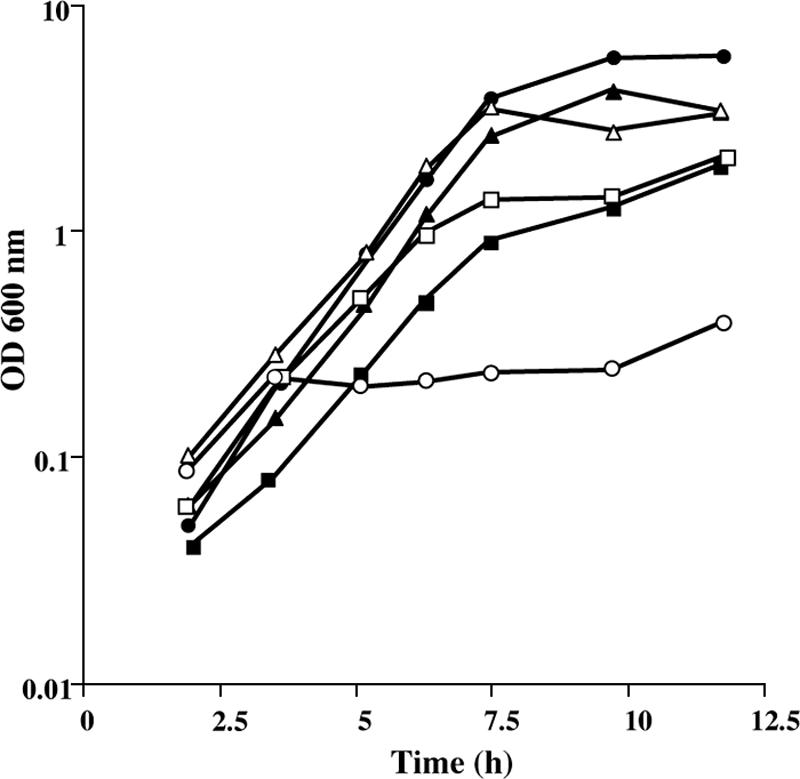

Methionine is converted to AdoMet by the AdoMet synthase MetK. The by-product of AdoMet-dependent methylation reactions is AdoHcy, which is degraded to homocysteine by the successive action of the MtnN and LuxS enzymes (Fig. 1). An mtnN mutant grows poorly in the presence of methionine as the sole sulfur source (49). Nevertheless, MtnN is a AdoHcy/MTA nucleosidase participating both in AdoMet recycling and in the methionine salvage pathway via MTR (Fig. 1). It is therefore not possible to conclude whether the production of homocysteine via AdoMet, AdoHcy, and S-ribosylhomocysteine is essential for the conversion of methionine to cysteine. A mutant with an inactivated luxS gene was thus constructed. The LuxS enzyme is involved in the degradation of S-ribosylhomocysteine to homocysteine with the concomitant production of AI-2, a signaling molecule of quorum sensing (46, 60). We first verified that the B. subtilis ΔluxS::cat mutant (BSIP1758) cannot produce AI-2. For this purpose, the ability of the wild-type and BSIP1758 strains to synthesize active AI-2 was determined using a V. harveyi reporter strain BB170 (8). In this system, the addition of cell-free supernatant from the wild-type strain stimulated light emission in V. harveyi, whereas bioluminescence was not increased by the addition of the supernatant prepared from the luxS mutant. To determine whether the AdoMet recycling pathway is necessary for the utilization of methionine, we compared the growth of the wild-type strain and the ΔluxS::cat mutant in minimal medium with 200 μM methionine, 200 μM homocysteine, 200 μM sulfate, or 100 μM cystine as the sole sulfur source. Both strains grew similarly with sulfate, homocysteine, or cystine (Fig. 2 and data not shown). In contrast, the ΔluxS::cat mutant grew poorly in the presence of methionine compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 2). This strongly suggests that methionine utilization requires first its conversion to homocysteine via the AdoMet recycling pathway. To study the possible involvement of the CysK, YrhA, and YrhB polypeptides in subsequent homocysteine degradation, the enzymatic activity of these proteins was determined.

FIG. 2.

Growth of the B. subtilis wild-type strain and ΔluxS mutant in the presence of various sulfur sources. Growth curves for strain 168 (solid symbols) or BSIP1758 ΔluxS::cat (open symbols) in the presence of 100 μM l-cystine (triangles), 200 μM dl-homocysteine (squares), or 200 μM l-methionine (circles).

Comparison of the enzymatic activity of the CysK and YrhA proteins.

Cystathionine β-synthases and OAS thiol-lyases belong to the same family of PLP-dependent enzymes (35). The B. subtilis cysK and yrhA genes encode proteins of this family. CysK and YrhA share similarities to the E. coli OAS thiol-lyases, CysK (55 and 39% identity, respectively) and CysM (43 and 35% identity, respectively). A rather low level of identity (35%) is observed between CysK and YrhA. Previous work indicates that CysK plays a major role in the sulfate assimilation pathway (59). The YrhAHis6 and CysKHis6 polypeptides were overproduced in E. coli, purified, and assayed in vitro. OAS thiol-lyase catalyzes the reaction of OAS and sulfide to give l-cysteine and acetate. We first measured the production of cysteine by using the method of Gaitonde. In the presence of 10 mM OAS and 10 mM Na2S, purified CysK produced 300 μmol of cysteine min−1 mg of protein−1, whereas purified YrhA merely produced 4 μmol of cysteine min−1 mg of protein−1. The release of acetate from OAS was also assayed by measuring the disappearance of NADH using coupled reactions catalyzed by actetate kinase, pyruvate kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase. YrhA was 100-fold less active than CysK. The OAS thiol-lyase activity was then measured in crude extracts of the wild-type and the ΔcysK strains grown with methionine. The activity was 1.5 μmol of cysteine min−1 mg of protein−1 for the wild-type strain and 0.07 μmol of cysteine min−1 mg of protein−1 for the cysK mutant in agreement with the data obtained with purified proteins. To study the involvement of YrhA and CysK in cysteine biosynthesis in vivo, we compared the growth of the wild-type strain, a ΔcysK mutant, or a ΔyrhA mutant (BFS2063) in the presence of 200 μM sulfate or 100 μM cystine. The wild-type and ΔyrhA strains grew similarly, with a doubling time of 60 min with sulfate and 50 min with cystine. In contrast, the doubling time of the ΔcysK mutant in the presence of sulfate increased up to 500 min. Surprisingly, the growth of a ΔcysK mutant also decreased in the presence of cystine, with a doubling time of 110 min and a reduced growth yield (data not shown). These results indicate that YrhA plays a minor role in sulfate assimilation and suggest another function for this protein.

We further examined the cystathionine β-synthase activity of YrhA and CysK. Cystathionine β-synthase catalyzes the reaction of homocysteine with serine to give cystathionine. In the presence of 10 mM homocysteine and 10 mM serine, no cystathionine was formed with purified YrhA and CysK using either an HPLC or a ninhydrin colorimetric assay. We then tested the possibility that OAS instead of serine could be a substrate for these enzymes. A specific activity of 4 μmol of cystathionine produced min−1 mg of protein−1 was observed with YrhA using the colorimetric assay. Under the same conditions, no cystathionine β-synthase activity was detected with CysK. The sulfur compound resulting from the reaction of OAS and homocysteine was determined by using HPLC. Cystathionine was detected only with purified YrhA.

YrhB, an enzyme with cystathionine-lyase and homocysteine γ-lyase activities in vitro.

YrhB shares 50% identity with the cystathionine β-lyase (MetC) from B. subtilis, 50% identity with the recently characterized cystathionine γ-lyase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (63), 46% identity with the cystathionine γ-lyases from rat and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (15), and 40 to 41% identity with the methionine γ-lyases from P. putida and Trichomonas vaginalis (25, 31). We had previously shown that YrhB has cysteine desulfhydrase activity in vitro (6). To analyze in more details the YrhB function, the protein was purified. Using an assay based on the rate of free-thiol group production, cysthathionine degradation was detected. The YrhB enzyme obeyed Michaelis-Menten kinetics with cystathionine as a substrate (data not shown). The apparent Km value, determined from Lineweaver-Burk plots, was 3 mM, and the Vmax was about 2 μmol of free thiol groups produced min−1 mg of protein−1. However, cystathionine degradation by cystathionine β-lyase or cystathionine γ-lyase leads to the production of different free-thiol containing compounds, homocysteine or cysteine, respectively. We thus tried to determine the sulfur compound resulting from cystathionine cleavage by YrhB using HPLC. Surprisingly, no significant amount of homocysteine or cysteine was detected after incubation of cystathionine with YrhB, despite the fact that this compound disappeared. Since YrhB has cysteine desulfhydrase activity in vitro (6), we propose that this enzyme could further produce sulfide from cysteine. In the presence of YrhB and cystathionine, sulfide formation was indeed detected with SPME-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (data not shown). At the same time, pyruvate was produced, which could in turn react with cysteine to give 2-methyl-2,4-thiazolidine-carboxylic acid, as previously observed (16, 64). Finally, addition of the cystathionine degradation product obtained in vitro with YrhB allowed a weak growth of a cysK cysM double mutant of E. coli (NK3), which is a cysteine auxotroph (data not shown). This mutant cannot grow in M63 medium with cystathionine or homocysteine. This result suggests that YrhB produces cysteine and has cystathionine γ-lyase activity (see Discussion).

We further examined whether YrhB can use homocysteine or methionine as a substrate. Homocysteine γ-lyase activity was monitored by detecting PbS formation after incubation of YrhB(His6) in the presence of 3 mM homocysteine and lead acetate (see Materials and Methods). A specific activity of 0.33 μmol of PbS produced min−1 mg of protein−1 was detected with purified YrhBHis6. Methionine γ-lyases directly produce methanethiol and α-ketobutyrate from methionine. No methionine γ-lyase activity was found for YrhB using 2 or 10 mM methionine as a substrate. Moreover, this activity could not be detected in crude extracts of the B. subtilis wild-type strain grown with methionine. These data indicate that there is no methionine γ-lyase in B. subtilis or that we failed to induce its synthesis.

Growth of E. coli in the presence of the B. subtilis yrhB gene.

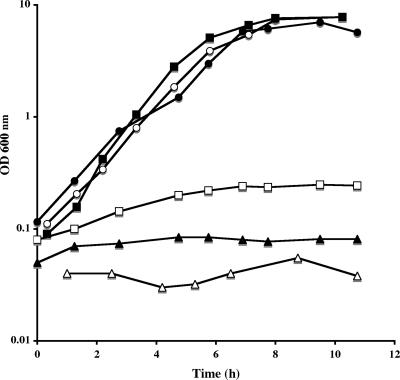

E. coli is unable to grow with cystathionine, homocysteine, or methionine as the sole sulfur source (21). We tested the ability of the B. subtilis yrhB gene to allow growth of E. coli with these sulfur sources. The yrhB gene was first cloned in pHT315 under the control of the lac promoter. E. coli FB8 strain containing either pHT315 or pHT315yrhB was grown in a sulfur-free M63 medium in the presence of sulfate, methionine, cystathionine, or homocysteine as the sole sulfur source. These two strains grew similarly on sulfate (data not shown). The presence of the yrhB gene in multicopy significantly increased the growth of strain FB8 with 1 mM homocysteine or 1 mM cystathionine compared to the same strain containing pHT315 alone (Fig. 3). In contrast, the presence of the yrhB gene in E. coli did not modify the poor growth of this bacterium with methionine (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Growth of an E. coli FB8 strain in the presence of pHT315 or pHT315yrhB. Growth curves for strain FB8(pHT315) (squares) or FB8(pHT315yrhB) (circles) in the presence of dl-homocysteine (open symbols) or dl-cystathionine (closed symbols).

Growth of B. subtilis mutants inactivated in the yrhA, yrhB, cysK, or cysE gene.

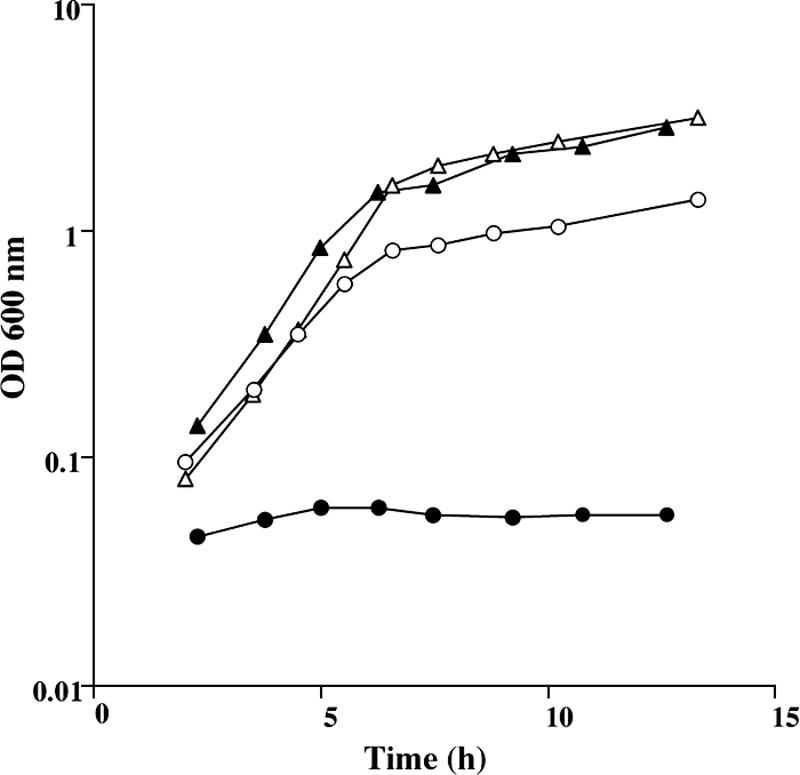

To investigate the role of YrhA, YrhB, and CysK in methionine utilization, we compared the growth of a ΔyrhA mutant (BFS2063), an yrhB mutant (BSIP1165), a ΔcysK mutant (BSIP1304), and the wild-type strain in the presence of 200 μM methionine. In the BFS2063 mutant, the genes downstream from yrhA are expressed under the control of the IPTG-inducible Pspac promoter to avoid a major polar effect (27). The yrhB and ΔcysK mutants grew similarly to the wild-type strain in the presence of methionine (Fig. 4). In contrast, the growth of the ΔyrhA mutant significantly decreased compared to the wild-type strain even when 1 mM IPTG was added (Fig. 4). The low residual growth observed with strain BFS2063 (ΔyrhA) was abolished in the presence of a cysK gene disruption (Fig. 4). This indicates that methionine utilization mostly requires YrhA. A ΔcysK ΔyrhA double mutant cannot grow with homocysteine, but significant growth was still observed in the presence of cystathionine (data not shown). B. subtilis therefore synthesizes cysteine from cystathionine without the intermediary production of homocysteine.

FIG. 4.

Growth of the B. subtilis wild-type strain and various mutants in the presence of methionine. Growth curves for strains 168 (•), BSIP1165 (yrhB::aphA3) (○), BSIP1304 (ΔcysK::spc) (▪), BFS2063 (ΔyrhA) (□), BSIP1870 (ΔyrhA ΔcysK::spc) (▴), or QB944 (cysE14) (▵) in the presence of 200 μM methionine. For strains BFS2063 and BSIP1870, 1 mM IPTG was added.

Since OAS is a substrate for the OAS thiol-lyase and the cystathionine β-synthase activity of YrhA, we tested the phenotype of a cysE14 mutant (QB944) lacking the serine O-acetyltransferase activity (17). The cysE mutant did not grow in the presence of 200 μM sulfate, 200 μM methionine and 200 μM homocysteine, whereas it grew with 100 μM cystine (data not shown). This indicates that CysE is necessary for sulfate assimilation and also for methionine and homocysteine conversion to cysteine.

The YrhB protein seems to be important both for the reverse transsulfuration and the sulfide-dependent pathways of the methionine-to-cysteine conversion (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, the yrhB mutant grew similarly to the wild-type strain in the presence of homocysteine or methionine (Fig. 4 and data not shown), suggesting the existence of bypass(es) for YrhB activity. We tested the growth of a ΔyrhAB ΔcysK mutant (BSIP1305) in the presence of cystathionine or homocysteine. A significant growth was observed in the presence of cystathionine, whereas the mutant did not grow in the presence of homocysteine (Fig. 5). Thus, a strain inactivated for CysK, YrhA, and YrhB is still able to synthesize directly cysteine from cystathionine.

FIG. 5.

Growth of the B. subtilis wild-type strain and ΔyrhABΔcysK mutant in the presence of cystathionine or homocysteine. Growth curves in cystathionine (open symbols) or homocysteine (closed symbols) for strains 168 (triangles) and BSIP1305 (ΔyrhAB::aphA3 ΔcysK::spc) (circles).

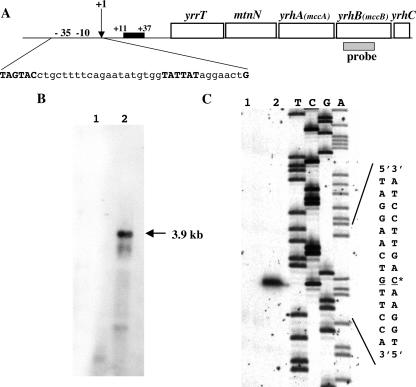

yrrTmtnNyrhABC operon.

Using transcriptome experiments, the expression of the yrhA, yrhB, and mtnN genes has been shown to decrease in the presence of sulfate (5). These genes, which are adjacent in the chromosome, may belong to the same operon. A Northern blot experiment with total RNA isolated from B. subtilis 168 grown with methionine or sulfate and hybridization with an yrhB-specific probe revealed a major 3.9-kb transcript (Fig. 6). This transcript was detected in RNA extracted from methionine-grown cells (Fig. 6B, lane 2) and absent from sulfate-grown cells (Fig. 6B, lane 1). The size expected for a mtnN yrhAB transcript is ∼3 kb. The yrrT and yrhC genes, located upstream and downstream of these genes, are transcribed in the same direction. Using yrrT- or yrhC-specific probes, we also detected the same 3.9-kb transcript (data not shown). The yrrT, mtnN, and yrhABC genes therefore form an operon (yrrTmtnNyrhABC). The transcription start site of the yrrTmtnNyrhABC operon was mapped by primer extension using RNA isolated from strain 168 grown with methionine or sulfate. A band was observed only in the reaction performed with RNA extracted from methionine-grown cells (Fig. 6C, lane 2). The transcription was initiated at a G residue located 59 bp upstream from the yrrT translational start site (Fig. 6A). The −10 region (TATTAT) is similar to the consensus sequence of σA-dependent promoters, whereas the deduced −35 region (TAGTAC) presents only low similarity with known B. subtilis promoters.

FIG. 6.

Genetic organization and characterization of the promoter of the yrrT operon. (A) The genetic organization of the yrrT operon is presented. The −35 and −10 regions are in uppercase letters, and the CymR binding site is indicated by a black box. (B) Northern blot analysis of the yrrT operon. B. subtilis 168 was grown in minimal medium with 1 mM sulfate (lane 1) or with 1 mM methionine (lane 2) as sulfur sources. The hybridization was performed with an yrhB-specific probe, which is indicated panel A. The arrow indicates the apparent size of the transcript detected. (C) Identification of the transcription start site of the yrrT operon by primer extension. Total RNA was extracted from B. subtilis 168 grown in minimal medium with 1 mM sulfate (lane 1) or 1 mM methionine (lane 2) as the sole sulfur source. The size of the extended product was compared to a DNA sequencing ladder of the yrrT promoter region. An asterisk marks the +1 site.

Expression of the yrrT operon in response to sulfur availability.

The expression of a pΔA(−108,+126)yrrT′-lacZ transcriptional fusion (18) was tested in the presence of different sulfur sources. The level of β-galactosidase activity was high in the presence of methionine (660 nmol of ONP mg of protein−1) and slightly reduced in the presence of homocysteine or cystathionine (360 nmol of ONP mg of protein−1). In the presence of sulfate or cysteine, the expression of this fusion was reduced 10- and 60-fold compared to the level of expression in the presence of methionine. Interestingly, the addition of 0.5 mM cysteine or 1 mM sulfate to methionine also repressed the expression of the yrrT′-lacZ fusion. In contrast, the addition of 50 μM cysteine did not modify yrrT expression. These results showed that the transcription of the yrrT operon was repressed by sulfate and cysteine at high concentrations in agreement with the role of MtnN, YrhA, and YrhB in the conversion of methionine to cysteine.

We have previously shown that CymR is involved in the sulfate-dependent repression of yrrT transcription and that OAS prevents the CymR-dependent binding to the yrrT promoter region (18). Albanesi et al. have shown that CysK, the OAS thiol-lyase, is a global regulator of genes participating in cysteine biosynthesis, including yrhA (1). To determine the role of CysE, the serine O-acetyltransferase and CysK in the regulation of the yrrT operon, the expression of the pΔAyrrT'-lacZ fusion was tested in a wild-type strain and in a cysE14 mutant, a ΔcysK mutant, or a cysE14 ΔcysK double mutant. Since the cysE14 and cysE14 ΔcysK mutants cannot grow with methionine, all of the strains were grown in minimal medium in the presence of methionine and cystine to an OD600 of 2 and then incubated for 2 h in the same medium with either 1 mM methionine or 250 μM cystine. The β-galactosidase activity was subsequently assayed (Table 2). In a wild-type background, the yrrT′-lacZ fusion was expressed with methionine and repressed eightfold with cystine, whereas the level of expression was low in a cysE14 mutant in both conditions. Moreover, addition of OAS to the growth medium containing cystine resulted in an increase of pyrrT′-lacZ expression (250 nmol of ONP mg of protein−1) compared to the level observed without OAS (40 nmol of ONP mg of protein−1). These results confirm the role of OAS in the signaling pathway controlling yrrT. In contrast, constitutive expression was observed with a ΔcymR, ΔcysK, or cysE14 ΔcysK mutant (Table 2). The yrrT derepression observed in a cysK mutant was probably not due to an accumulation of OAS in the absence of the major OAS thiol-lyase but rather to a more direct role of CysK, as proposed for cysH regulation (1).

TABLE 2.

Expression of a transcriptional p(−108, +126)yrrT′-lacZ fusion in the presence of methionine or cystine in various B. subtilis strainsa

| Strain | Genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (nmol of ONP min−1 mg of protein−1)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Methionine (1 mM) | Cystine (0.25 mM) | ||

| BSIP 1144 | p(−108, +126) yrrT′-lacZ | 450 | 55 |

| BSIP 1314 | p(−108, +126) yrrT′-lacZ cysK::spc | 580 | 410 |

| BSIP 1837 | p(−108, +126) yrrT′-lacZ cysE14 | 3 | 6 |

| BSIP 1840 | p(−108, +126) yrrT′-lacZ cysK::spc cysE14 | 310 | 430 |

| BSIP 1794 | p(−108, +126) yrrT′-lacZ cymR::aphA3 | 490 | 480 |

Cells were grown in minimal medium containing 1 mM methionine and 0.25 mM cystine until they reached an OD600 of 2. They were then centrifuged, washed three times in minimal medium without any added sulfur source, and resuspended in minimal medium containing either 1 mM methionine or 0.25 mM cystine. Cells were harvested 2 h after resuspension.

Involvement of CysK in the CymR-dependent binding to the yrrT promoter region.

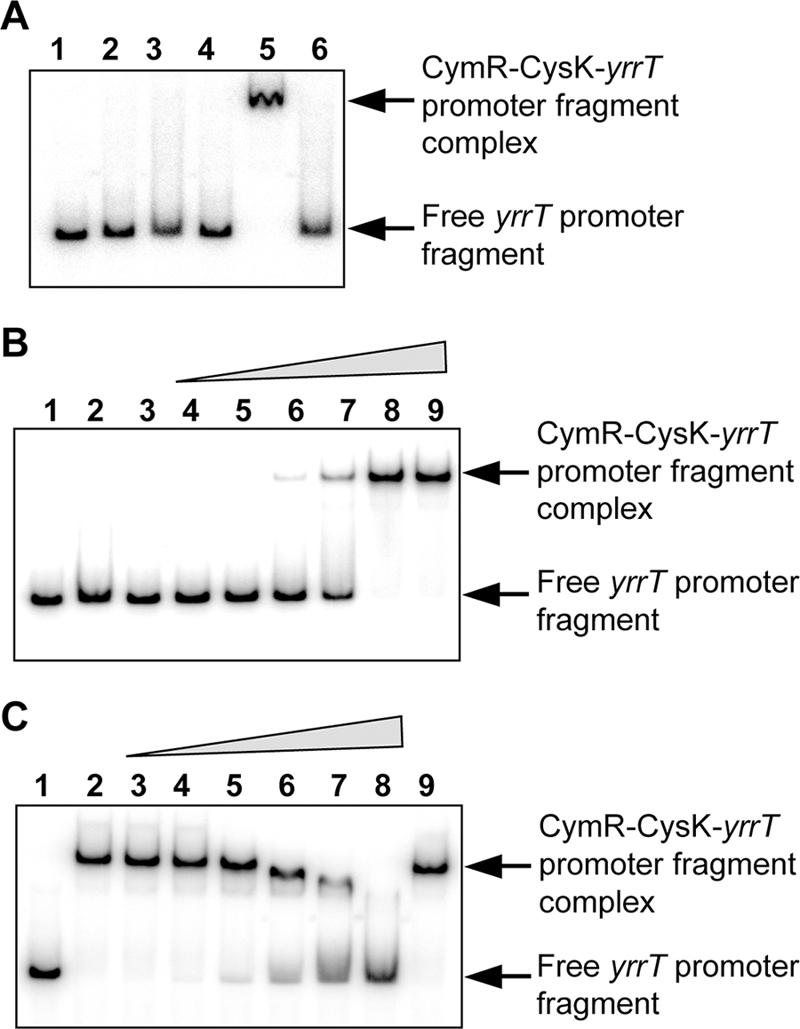

A CymR-dependent binding to the yrrT promoter region has been observed using crude extracts of E. coli DH5α overproducing CymR (18). To determine whether CysK or CysM from E. coli participated to this binding, pDIA5735 (pxylA-cymR) or pXT were used to transform an E. coli cysK cysM double mutant (NK3). Crude extracts of NK3 producing or not CymR were used in mobility shift DNA-binding assays with a labeled DNA fragment containing the yrrT promoter region (−108 to +126). No complex was formed in the presence of 7.5 μg of crude extracts of NK3 carrying either pDIA5735 or pXT (Fig. 7A, lanes 2 and 3), whereas a protein-DNA complex was observed with 7.5 μg of crude extracts of DH5α carrying pDIA5735 (data not shown). The addition of 0.1 or 0.3 μg of purified CysK from B. subtilis restored the formation of the protein-DNA complex in the presence of crude extracts of NK3 carrying pDIA5735 (Fig. 7A, lane 5). The same result was not obtained when YrhA replaced CysK (Fig. 7A, lane 6). These results strongly suggest that both CymR and CysK are required to observe a gel shift with the yrrT promoter region.

FIG. 7.

CymR- and CysK-dependent binding to the yrrT promoter region. (A) Gel mobility shift experiments were performed by incubating crude extracts of a cysK cysM double mutant of E. coli (NK3) (7.5 μg of proteins) carrying either pXT (lanes 2 and 4) or pDIA5735 (pxylA-cymR) (lanes 3, 5, and 6) with 5′-radiolabeled DNA fragments containing the yrrT promoter region. A total of 0.3 μg of purified CysK protein (lanes 4 and 5) or 0.3 μg of purified YrhA protein (lane 6) was added to the reaction mixture. Lane 1, free probe. (B) Binding of the purified CysK and CymR proteins to the yrrT promoter region. Lane 1, free probe, lane 2, 1 μg of purified CymR protein added; lane 3, 1 μg of purified CysK protein added; lanes 4 to 9, increasing amounts of CymR and CysK proteins added at a 1:1 molar ratio (50:100 ng, 75:150 ng, 100:200 ng, 150:300 ng, 200:400 ng, and 250:500 ng of CymR and CysK proteins, respectively). (C) Negative effect of OAS on the binding of the CymR-CysK complex to the yrrT promoter region. Lane 1, free probe; lanes 2 to 9, 250 ng of CymR and 500 ng of CysK. Lanes 3 to 8 show results with increasing amounts of OAS (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mM, respectively). Lane 9, 5 mM NAS.

For further analysis, we purified a native CymR protein by using the CBD system. The ability of purified native CymR protein to interact with the yrrT promoter region in the presence or absence of CysK was then tested in gel shift experiments. No binding was observed in the presence of 1 μg of purified CymR or CysK alone (Fig. 7B, lanes 2 and 3). However, a complex was formed when increasing amounts of both CymR and CysK at a 1:1 molar ratio were added to the yrrT promoter fragment (Fig. 7B, lanes 4 to 9). Indeed, 200 ng of CymR and 400 ng of CysK were sufficient for the full retardation of the DNA fragment (Fig. 7B, lane 8).

OAS prevents the CymR-dependent binding to the yrrT promoter in mobility shift experiments with crude extracts containing CymR (18). Similarly, the addition of increasing concentrations of OAS (0.1 to 5 mM) to the binding assay resulted in the release of the probe from the CymR-CysK protein-DNA complex (Fig. 7C, lanes 3 to 8). The formation of this complex was strongly reduced in the presence of 2 mM OAS (Fig. 7C, lane 7). Moreover, the negative effect of OAS is specific, since its analogous compound, NAS, at 5 mM is unable to dissociate the DNA-protein complex (Fig. 7C, lane 9).

DISCUSSION

As observed for other bacteria such as K. aerogenes, P. putida, P. aeruginosa, and M. tuberculosis (48, 61, 63), B. subtilis is able to grow in the presence of methionine, homocysteine, and cystathionine as a sulfur source, indicating the existence of an efficient conversion of these compounds to cysteine. A luxS mutant inactivated for one step of the AdoMet recycling pathway (Fig. 1) grows poorly in the presence of methionine (Fig. 2). Methionine utilization in B. subtilis mostly proceeds via the formation of homocysteine using the AdoMet recycling pathway. In this way, methanethiol and methanesulfonate are not intermediary compounds in the methionine-to-cysteine conversion as proposed in P. putida (61). In agreement with these results, neither methionine γ-lyase activity nor methanethiol is detected in the culture of B. subtilis (47; the present study work; S. Auger, unpublished results). Moreover, a mutant inactivated for the ssuD gene encoding the monooxygenase required for aliphatic sulfonates utilization (Fig. 1) is still able to grow in the presence of methionine as the sole sulfur source (I. Martin-Verstraete, unpublished results). The LuxS enzyme is involved in the production of AI-2, a universal signaling factor for interspecies communication (46, 60). AI-2 is generated by the spontaneous cyclization of 4,5-dihydroxyl-2,3-pentanedione, which is produced during the two-step recycling pathway of AdoHcy into homocysteine involving MtnN and LuxS (Fig. 1). As recently shown (32), a B. subtilis luxS mutant is unable to produce AI-2. In B. subtilis, the luxS gene is monocistronic. The mtnN gene, which encodes the AdoHcy nucleosidase (Fig. 1), forms an operon together with yrhA, yrhB, a gene encoding a putative AdoMet-dependent methyltransferase (yrrT), and yrhC (Fig. 6). Interestingly, either luxS or mtnN form an operon with yrhA-, yrhB-, and yrrT-like genes in Bacillus cereus, Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus stearothermophilus, Oceanobacillus iheyensis, Clostridium perfringens, and Clostridium botulinum (40, 43). The YrhA and YrhB proteins, which belong to the OAS thiol-lyase and cystathionine γ-synthase family of proteins, respectively, are good candidates for the conversion of homocysteine to cysteine.

Both YrhA and CysK proteins have an OAS thiol-lyase activity in vitro in agreement with previous results, indicating that a double ΔcysK ΔyrhA mutant is unable to grow with sulfate (59). However, several findings indicate that CysK is the major OAS thiol-lyase required for sulfate assimilation in B. subtilis. First, the growth of a ΔcysK mutant is strongly reduced in the presence of sulfate, whereas a ΔyrhA mutant grows similarly to the wild-type strain. Moreover, the OAS thiol-lyase activity of CysK is 75-fold higher than that of YrhA. In contrast, cystathionine β-synthase activity was only observed in vitro with YrhA. Cystathionine β-synthases are usually 150 amino acids longer in their C-terminal region than OAS thiol-lyases (14, 15, 41). YrhA is more closely related to OAS thiol-lyases, as indicated by its size and its similarities. Nevertheless, YrhA has both OAS thiol-lyase and cystathionine β-synthase activities in vitro, like the enzymes of Aeropyrum pernix and Trypanosoma cruzi (37, 39). Serine is the substrate of cystathionine β-synthases from mammals and microorganisms, whereas YrhA uses OAS instead of serine in the conditions tested. As proposed by Mino and Ishikawa (37), the enzymes with cystathionine β-synthase and OAS thiol-lyase activities could have retained some properties of an ancestral protein that would have diverged later into individual enzymes with narrower or different substrate specificity.

In B. subtilis, a ΔcysK mutant grows normally with methionine as the sole source of sulfur. Despite the fact that yrhA is constitutively expressed at a high level in the cysK mutant (Table 2) (1), CysK still represents 95% of the OAS thiol-lyase activity. In contrast, the ΔyrhA mutant grows poorly in the presence of methionine, as observed for an yrhA-like mutant of Lactococcus lactis and a cbs (cystathionine β-synthase probable gene) mutant of Streptomyces venezuelae (14, 52). The drastic growth defect of the B. subtilis ΔyrhA mutant in the presence of methionine is most probably due to the cystathionine β-synthase activity of YrhA rather than to its low OAS thiol-lyase activity in the presence of the major OAS thiol-lyase, CysK. YrhA seems therefore to correspond to the first step of the reverse transsulfuration pathway (Fig. 1). The growth of a ΔcysK ΔyrhA double mutant with cystathionine but not with homocysteine strongly suggests that a cystathionine γ-lyase, the second step of the reverse transsulfuration pathway, is also present in B. subtilis. YrhB has cystathionine lyase, homocysteine γ-lyase, and cysteine desulfhydrase activities in vitro (6; this study). Surprisingly, we fail to detect significant production of cysteine from cystathionine in the presence of YrhB using HPLC. This could be due to the further degradation of cysteine by the cysteine desulfhydrase activity of YrhB. However, several results strongly suggest that YrhB is a cystathionine γ-lyase rather than a cystathionine β-lyase, an enzyme involved in methionine biosynthesis (Fig. 1). (i) The expression of the yrhB gene is high with methionine and reduced with sulfate or cysteine. (ii) Two cystathionine β-lyases, MetC and PatB, have already been characterized in B. subtilis. A patB metC double mutant did not grow with cystathionine, indicating that there is no third cystathionine β-lyase (6). The normal growth of a B. subtilis yrhB mutant raises the question of the physiological role of the corresponding enzyme in vivo. The significant growth of E. coli with homocysteine in the presence of the yrhB gene indicates that YrhB may function as a homocysteine γ-lyase in vivo in E. coli, leading to the production of sulfide, which can in turn form cysteine with CysK (28). Physiological evidence for the participation of YrhB in the reverse transsulfuration pathway is lacking. Indeed, a strain inactivated for CysK, YrhA, and YrhB is still able to synthesize cysteine from cystathionine without the intermediary production of homocysteine. An alternative cystathionine γ-lyase different from yrhB is probably present in B. subtilis. The identification of this second cystathionine γ-lyase and its role in methionine degradation deserve further investigation.

The YrhA and YrhB proteins, which participate in the methionine-to-cysteine conversion pathway in B. subtilis, are renamed MccA and MccB, respectively. In agreement with its role in this conversion, the expression of the yrrT operon is repressed in the presence of cysteine and sulfate. We unraveled some features of the control of yrrT expression in response to sulfur availability. Recent data indicate that CymR and CysK, the major OAS thiol-lyase of B. subtilis, are global regulators of cysteine metabolism and that OAS plays a key role in the CysK- and CymR-dependent regulations (1, 18). We have shown that crude extracts from E. coli containing CymR interact with the yrrT promoter region only in the presence of CysM and/or CysK from E. coli (Fig. 7A). Purified B. subtilis CymR or CysK alone cannot bind to DNA, whereas the addition of proteins in a molar ratio of one to one allows the formation of a protein-DNA complex (Fig. 7B). Thus, both CysK and CymR are required for DNA binding. It is worth noting that CysK or CysM from E. coli, which shares 55 and 43% identity with CysK from B. subtilis, seem to assist CymR-dependent binding. This suggests that conserved amino acids in OAS thiol-lyases from these two organisms are involved in CymR and CysK interaction. CysK does not contain any DNA-binding motif, whereas CymR, an Rrf2-type repressor, has a typical helix-turn-helix motif. We may then propose that the probable formation of a CysK-CymR complex induces conformational changes to help the CymR-dependent binding to its targets. Interestingly, the glutamine synthase of B. subtilis also directly interacts with the global regulator of nitrogen assimilation TnrA (65). OAS is required for the transcription of the cysH, ssu, and yrrT operons and ytlI, encoding the activator of the ytmI operon (13, 38, 58; the present study). As observed for the cysH operon (1), yrrT is actively transcribed regardless of the absence of OAS in a cysK background (Table 2). OAS modulates the interaction of the CymR-CysK probable complex with DNA. CysK may be a good candidate for sensing the cysteine pool of the cell by the regulatory complex. Indeed, OAS, which is a substrate of CysK, binds to the active site of this enzyme. Whether OAS binding dissociates the CymR-CysK complex or decreases the affinity of this complex for DNA deserves further investigation. For the cysH operon, Albanesi et al. (1) have proposed that CysK may interact with an uncharacterized repressor, CysR, to promote its binding to the cysH promoter. Further experiments are needed to determine the existence of a unique repressor or two distinct regulators, CysR and CymR. Cysteine probably limits the size of the intracellular pool of OAS, leading to CymR-dependent repression. As observed for E. coli, CysE activity may be feedback inhibited by cysteine (28). In B. subtilis, cysE expression is also regulated by transcription antitermination at a cysteine-specific T-box (19). Thus, the level of OAS in microorganisms may be correlated with the level of uncharged cysteinyl-tRNA, which signals the cysteine status in the cell. A cysE mutant inactivated for the serine O-acetyltransferase is unable to grow with methionine or homocysteine. OAS plays a key role in the methionine-to-cysteine conversion both as a substrate for CysK and MccA and as a signaling molecule for the sulfur-dependent control of the yrrT operon. In E. coli and L. lactis, OAS or its derivative, NAS, also plays a crucial role in the signaling pathway controlling the CysB and the CmbR/FhuR regulons (30, 52).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to P. Polard for the gift of pTYB11, to P. Bonnarme for helping to detect the methanethiol, and to D. Le Bars for help with the HPLC and SPME-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses. We thank G. Rapoport for critical reading of the manuscript.

This research was supported by grants from the ANR (Dynamocell NT05-2-44860]), the Ministère de l'Education Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (URA 2171), the Institut Pasteur, and the Université Paris 7.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albanesi, D., M. C. Mansilla, G. E. Schujman, and D. de Mendoza. 2005. Bacillus subtilis cysteine synthetase is a global regulator of the expression of genes involved in sulfur assimilation. J. Bacteriol. 187:7631-7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amarita, F., M. Yvon, M. Nardi, E. Chambellon, J. Delettre, and P. Bonnarme. 2004. Identification and functional analysis of the gene encoding methionine-γ-lyase in Brevibacterium linens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7348-7354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arantès, O., and D. Lereclus. 1991. Construction of cloning vectors for Bacillus thuringiensis. Gene 108:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashida, H., Y. Saito, C. Kojima, K. Kobayashi, N. Ogasawara, and A. Yokota. 2003. A functional link between RuBisCO-like protein of Bacillus and photosynthetic RuBisCO Science 302:286-290. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Auger, S., A. Danchin, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 2002. Global expression profile of Bacillus subtilis grown in the presence of sulfate or methionine. J. Bacteriol. 184:5179-5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auger, S., M. P. Gomez, A. Danchin, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 2005. The PatB protein of Bacillus subtilis is a C-S-lyase. Biochimie 87:231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auger, S., W. H. Huen, A. Danchin, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 2002. The metIC operon involved in methionine biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis is controlled by transcription antitermination. Microbiology 148:507-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassler, B. L., M. Wright, R. E. Showalter, and M. R. Silverman. 1993. Intercellular signaling In Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes regulating expression of luminescence. Mol. Microbiol. 9:773-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berndt, C., C. H. Lillig, M. Wollenberg, E. Bill, M. C. Mansilla, D. de Mendoza, A. Seidler, and J. D. Schwenn. 2004. Characterization and reconstitution of a 4Fe-4S adenylyl sulfate/phosphoadenylyl sulfate reductase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:7850-7855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnarme, P., L. Psoni, and H. E. Spinnler. 2000. Diversity of l-methionine catabolism pathways in cheese-ripening bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5514-5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruni, C. B., V. Colantuoni, L. Sbordone, R. Cortese, and F. Blasi. 1977. Biochemical and regulatory properties of Escherichia coli K-12 his mutants. J. Bacteriol. 130:4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burbank, H. M., and M. C. Quian. 2005. Volatile sulfur compounds in Cheddar cheese determined by headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatograph-pulsed flame photometric detection. J. Chromatogr. 1066:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burguière, P., J. Fert, I. Guillouard, S. Auger, A. Danchin, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 2005. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis ytmI operon, involved in sulfur metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 187:6019-6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang, Z., and L. C. Vining. 2002. Biosynthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids in Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230: roles for cystathionine β-synthase and transsulfuration. Microbiology 148:2135-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherest, H., D. Thomas, and Y. Surdin-Kerjan. 1993. Cysteine biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae occurs through the transsulfuration pathway, which has been built up by enzyme recruitment. J. Bacteriol. 175:5366-5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dassler, T., T. Maier, C. Winterhalter, and A. Bock. 2000. Identification of a major facilitator protein from Escherichia coli involved in efflux of metabolites of the cysteine pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1101-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dedonder, R. A., J.-A. Lepesant, J. Lepesant-Kejzlarová, A. Billault, M. Steinmetz, and F. Kunst. 1977. Construction of a kit of reference strains for rapid genetic mapping in Bacillus subtilis 168. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 33:989-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Even, S., P. Burguière, S. Auger, O. Soutourina, A. Danchin, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 2006. Global control of cysteine metabolism by CymR in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188:2184-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagnon, Y., R. Breton, H. Putzer, M. Pelchat, M. Grunberg-Manago, and J. Lapointe. 1994. Clustering and co-transcription of the Bacillus subtilis genes encoding the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases specific for glutamate and for cysteine and the first enzyme for cysteine biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 269:7473-7482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaitonde, M. K. 1967. A spectrophotometric method for the direct determination of cysteine in the presence of other naturally occurring amino acids. Biochem. J. 104:627-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene, R. C. 1996. Biosynthesis of methionine, p. 542-560. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 22.Grunau, J. A., and J. M. Swiader. 1992. Chromatography of 99 amino acids and other ninhydrin-reactive compounds in the Pickering lithium gradient system. J. Chromatogr. 594:165-171. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillouard, I., S. Auger, M. F. Hullo, F. Chetouani, A. Danchin, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 2002. Identification of Bacillus subtilis CysL, a regulator of the cysJI operon, which encodes sulfite reductase. J. Bacteriol. 184:4681-4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hulanicka, M. D., C. Garrett, G. Jagura-Burdzy, and N. M. Kredich. 1986. Cloning and characterization of the cysAMK region of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 168:322-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue, H., K. Inagaki, S. I. Eriguchi, T. Tamura, N. Esaki, K. Soda, and H. Tanaka. 1997. Molecular characterization of the mde operon involved in l-methionine catabolism of Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 179:3956-3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashiwamata, S., and D. M. Greenberg. 1970. Studies on cystathionine synthase of rat liver properties of the highly purified enzyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 212:488-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi, K., S. D. Ehrlich, A. Albertini, G. Amati, K. K. Andersen, M. Arnaud, K. Asai, S. Ashikaga, S. Aymerich, P. Bessieres, F. Boland, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, K. Bunai, J. Chapuis, L. C. Christiansen, A. Danchin, M. Debarbouille, E. Dervyn, E. Deuerling, K. Devine, S. K. Devine, O. Dreesen, J. Errington, S. Fillinger, S. J. Foster, Y. Fujita, A. Galizzi, R. Gardan, C. Eschevins, T. Fukushima, K. Haga, C. R. Harwood, M. Hecker, D. Hosoya, M. F. Hullo, H. Kakeshita, D. Karamata, Y. Kasahara, F. Kawamura, K. Koga, P. Koski, R. Kuwana, D. Imamura, M. Ishimaru, S. Ishikawa, I. Ishio, D. Le Coq, A. Masson, C. Mauel, R. Meima, R. P. Mellado, A. Moir, S. Moriya, E. Nagakawa, H. Nanamiya, S. Nakai, P. Nygaard, M. Ogura, T. Ohanan, M. O'Reilly, M. O'Rourke, Z. Pragai, H. M. Pooley, G. Rapoport, J. P. Rawlins, L. A. Rivas, C. Rivolta, A. Sadaie, Y. Sadaie, M. Sarvas, T. Sato, H. H. Saxild, E. Scanlan, W. Schumann, J. Seegers, J. Sekiguchi, A. Sekowska, S. J. Seror, M. Simon, P. Stragier, R. Studer, H. Takamatsu, T. Tanaka, M. Takeuchi, H. B. Thomaides, V. Vagner, J. M. van Dijl, K. Watabe, A. Wipat, H. Yamamoto, M. Yamamoto, Y. Yamamoto, K. Yamane, K. Yata, K. Yoshida, H. Yoshikawa, U. Zuber, and N. Ogasawara. 2003. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4678-4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kredich, N. M. 1996. Biosynthesis of cysteine, p. 514-527. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 29.Kunst, F., and G. Rapoport. 1995. Salt stress is an environmental signal affecting degradative enzyme synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:2403-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lochowska, A., R. Iwanicka-Nowicka, D. Plochocka, and M. M. Hryniewicz. 2001. Functional dissection of the LysR-type CysB transcriptional regulator: regions important for DNA binding, inducer response, oligomerization and positive control. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2098-2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lockwood, B. C., and G. H. Coombs. 1991. Purification and characterization of methionine γ-lyase from Trichomonas vaginalis. Biochem. J. 279:675-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lombardia, E., A. J. Rovetto, A. L. Arabolaza, and R. R. Grau. 2006. A LuxS-dependent cell-to-cell language regulates social behavior and development in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188:4442-4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mansilla, M. C., D. Albanesi, and D. de Mendoza. 2000. Transcriptional control of the sulfur-regulated cysH operon, containing genes involved in l-cysteine biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:5885-5892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansilla, M. C., and D. de Mendoza. 2000. The Bacillus subtilis cysP gene encodes a novel sulphate permease related to the inorganic phosphate transporter (Pit) family. Microbiology 146:815-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta, P. K., and P. Christen. 2000. The molecular evolution of pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes. Adv. Enzymol. 74:129-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 37.Mino, K., and K. Ishikawa. 2003. Characterization of a novel thermostable O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Aeropyrum pernix K1. J. Bacteriol. 185:2277-2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munier, H., A. M. Gilles, P. Glaser, E. Krin, A. Danchin, R. Sarfati, and O. Barzu. 1991. Isolation and characterization of catalytic and calmodulin-binding domains of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase. Eur. J. Biochem. 196:469-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nozaki, T., Y. Shigeta, Y. Saito-Nakano, M. Imada, and W. D. Kruger. 2001. Characterization of transsulfuration and cysteine biosynthetic pathways in the protozoan hemoflagellate, Trypanosoma cruzi: isolation and molecular characterization of cystathionine β-synthase and serine acetyltransferase from Trypanosoma. J. Biol. Chem. 276:6516-6523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohtani, K., H. Takamura, H. Yaguchi, H. Hayashi, and T. Shimizu. 2000. Genetic analysis of the ycgJ-metB-cysK-ygaG operon negatively regulated by the VirR/VirS system in Clostridium perfringens. Microbiol. Immunol. 44:525-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ono, B., K. Kijima, T. Inoue, S. Miyoshi, A. Matsuda, and S. Shinoda. 1994. Purification and properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cystathionine β-synthase. Yeast 10:333-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ravanel, S., M. Droux, and R. Douce. 1995. Methionine biosynthesis in higher plants. I. Purification and characterization of cystathionine γ-synthase from spinach chloroplasts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 316:572-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodionov, D. A., A. G. Vitreschak, A. A. Mironov, and M. S. Gelfand. 2004. Comparative genomics of the methionine metabolism in gram-positive bacteria: a variety of regulatory systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:3340-3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruzheinikov, S. N., S. K. Das, S. E. Sedelnikova, A. Hartley, S. J. Foster, M. J. Horsburgh, A. G. Cox, C. W. McCleod, A. Mekhalfia, G. M. Blackburn, D. W. Rice, and P. J. Baker. 2001. The 1.2 Å structure of a novel quorum-sensing protein, Bacillus subtilis LuxS. J. Mol. Biol. 313:111-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 46.Schauder, S., K. Shokat, M. G. Surette, and B. L. Bassler. 2001. The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 41:463-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Segal, W., and R. L. Starkey. 1969. Microbial decomposition of methionine and identity of the resulting sulfur products. J. Bacteriol. 98:908-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seiflein, T. A., and J. G. Lawrence. 2001. Methionine-to-cysteine recycling in Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 183:336-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sekowska, A., and A. Danchin. 1999. Identification of yrrU as the methylthioadenosine nucleosidase gene in Bacillus subtilis. DNA Res. 6:255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sekowska, A., and A. Danchin. 2002. The methionine salvage pathway in Bacillus subtilis. BMC Microbiol. 2:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soda, K., H. Tanaka, and N. Esaki. 1983. Multifunctional biocatalysis: methionine γ-lyase. Trends Biochem. Sci. 8:214-217. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sperandio, B., P. Polard, D. S. Ehrlich, P. Renault, and E. Guedon. 2005. Sulfur amino acid metabolism and its control in Lactococcus lactis IL1403. J. Bacteriol. 187:3762-3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stülke, J., I. Martin-Verstraete, M. Zagorec, M. Rose, A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 1997. Induction of the Bacillus subtilis ptsGHI operon by glucose is controlled by a novel antiterminator, GlcT. Mol. Microbiol. 25:65-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka, H., N. Esaki, and K. Soda. 1985. A versatile bacterial enzyme: l-methionine γ-lyase. Enzyme Microb. Technol 7:530-537. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas, D., and Y. Surdin-Kerjan. 1997. Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:503-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thong, K. W., and G. H. Coombs. 1985. Homocysteine desulphurase activity in trichomonads. IRCS Med. Sci. 13:493-494. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uren, J. R. 1987. Cystathionine β-lyase from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 143:483-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Ploeg, J. R., M. Barone, and T. Leisinger. 2001. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis sulphonate-sulphur utilization genes is regulated at the levels of transcription initiation and termination. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1356-1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Ploeg, J. R., M. Barone, and T. Leisinger. 2001. Functional analysis of the Bacillus subtilis cysK and cysJI genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 201:29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vendeville, A., K. Winzer, K. Heurlier, C. M. Tang, and K. R. Hardie. 2005. Making “sense” of metabolism: autoinducer-2, LuxS, and pathogenic bacteria. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 3:383-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vermeij, P., and M. A. Kertesz. 1999. Pathways of assimilative sulfur metabolism in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 181:5833-5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wach, A. 1996. PCR-synthesis of marker cassettes with long flanking homology regions for gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 12:259-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wheeler, P. R., N. G. Coldham, L. Keating, S. V. Gordon, E. E. Wooff, T. Parish, and R. G. Hewinson. 2005. Functional demonstration of reverse transsulfuration in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex reveals that methionine is the preferred sulfur source for pathogenic mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 280:8069-8078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wlodek, L., and J. Czubak. 1984. Formation of 2-methyl-2,4-thiazolidinedicarboxylic acid from l-cysteine in rat tissues. Acta Biochim. Pol. 31:279-283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wray, L. V., J. M. Zalieckas, and S. H. Fisher. 2001. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase controls gene expression through a protein-protein interaction with transcription factor TnrA. Cell 107:427-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yocum, R. R., J. B. Perkins, C. L. Howitt, and J. Pero. 1996. Cloning and characterization of the metE gene encoding S-adenosylmethionine synthetase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:4604-4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yvon, M., E. Chambellon, A. Bolotin, and F. Roudot-Algaron. 2000. Characterization and role of the branched-chain aminotransferase (BcaT) isolated from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris NCDO 763. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:571-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yvon, M., S. Thirouin, L. Rijnen, D. Fromentier, and J. C. Gripon. 1997. An aminotransferase from Lactococcus lactis initiates conversion of amino acids to cheese flavor compounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:414-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]