Abstract

Moraxella catarrhalis is a human-restricted pathogen that can cause respiratory tract infections. In this study, we identified a previously uncharacterized 24-kDa outer membrane protein with a high degree of similarity to Neisseria Opa protein adhesins, with a predicted β-barrel structure consisting of eight antiparallel β-sheets with four surface-exposed loops. In striking contrast to the antigenically variable Opa proteins, the M. catarrhalis Opa-like protein (OlpA) is highly conserved and constitutively expressed, with 25 of 27 strains corresponding to a single variant. Protease treatment of intact bacteria and isolation of outer membrane vesicles confirm that the protein is surface exposed yet does not bind host cellular receptors recognized by neisserial Opa proteins. Genome-based analyses indicate that OlpA and Opa derive from a conserved family of proteins shared by a broad array of gram-negative bacteria.

Moraxella catarrhalis is an obligate parasite of humans that can cause disease in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts. In the upper respiratory tract, M. catarrhalis is responsible for cases of sinusitis and is the third leading cause of otitis media in infants, after only Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae (5, 10, 18, 24). In the lower respiratory tract, M. catarrhalis can cause respiratory infections in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality of these patients (27, 28). M. catarrhalis is thought to be responsible for 2 to 4 million infectious exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United States each year (25), and there is significant cost in treating disease related to M. catarrhalis, which is complicated in part by a rise in antibiotic-resistant strains (2, 30). This makes development of a vaccine an exciting and important goal.

The mechanisms involved in pathogenesis and virulence of M. catarrhalis remain poorly defined. Attachment to host mucosal surfaces is an important step in colonization. Recently, M. catarrhalis genes encoding the type IV pilus were identified and characterized (23), leading to speculation that this structure mediates initial attachment to mucosal epithelia in a manner similar to that of the closely related pathogenic Neisseria spp. (9). M. catarrhalis can also interact with the A549 human lung epithelial carcinoma cell line through the bacterium's outer membrane protein CD (16) and Hag (17) adhesins. Another adhesin, UspA1, promotes attachment to Chang human conjunctiva-derived epithelial cells (21) and was recently shown to mediate adherence via the host cellular receptor CEACAM1 (15). Human CEACAM1 is also engaged by the adhesins of other bacteria, including the Haemophilus influenzae P5 protein (14) and the Opa proteins of pathogenic and commensal Neisseria spp. (12, 29, 35). Remarkably, the UspA1, P5, and Opa proteins are not related, indicating a clear example of convergent evolution by these various human-restricted bacteria.

Considering the importance of the Opa family of outer membrane proteins in neisserial pathogenesis, we sought to determine whether homologues of neisserial Opa proteins exist in M. catarrhalis. A genome-wide screen of M. catarrhalis revealed a single gene with high homology to the neisserial Opa proteins. Herein, we characterize this previously unidentified 24-kDa Opa-like protein A of M. catarrhalis (OlpA) and establish it as an outer membrane protein that is highly conserved among clinical strains. Based upon broader analyses, we also reveal that OlpA is a member of a highly conserved family of proteins conserved across a wide variety of gram-negative bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The M. catarrhalis strains employed in this study are listed in Table 1. Several of these strains, including O35E (1), O46E (21), TTA37 (21), 7169 (22), and 4223 (19), have been described previously. For preparation of whole-cell lysates, M. catarrhalis strains were grown at 37°C on brain heart infusion (Difco/Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) agar plates in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 or in liquid broth. Escherichia coli strains employed in this study were strain EPI300 with plasmids indicated under “Cloning the gene” below. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates or broth with standard antibiotic supplementation as required.

TABLE 1.

M. catarrhalis strains used in this study

| Strain | Source |

|---|---|

| ATCC 43617 | ATCC |

| O35E | John D. Nelson, Texas |

| O46E | John D. Nelson, Texas |

| TTA37 | Steven L. Berk, Tennessee |

| 7169 | Anthony A. Campagnari, New York |

| ATCC 25238 | ATCC |

| 4223 | Timothy F. Murphy, New York |

| V1171 | Frederick Henderson, North Carolina |

| V1156 | Frederick Henderson, North Carolina |

| V1145 | Frederick Henderson, North Carolina |

| V1120 | Frederick Henderson, North Carolina |

| V1118 | Frederick Henderson, North Carolina |

| V1069 | Frederick Henderson, North Carolina |

| P44 | Steven L. Berk, Tennessee |

| FR3227 | Richard J. Wallace, Texas |

| FR2336 | Richard J. Wallace, Texas |

| FR2213 | Richard J. Wallace, Texas |

| FIN2406 | Merja Helminen, Finland |

| FIN2344 | Merja Helminen, Finland |

| FIN2341 | Merja Helminen, Finland |

| FIN2265 | Merja Helminen, Finland |

| ETSU-26 | Steven L. Berk, Tennessee |

| ETSU-22 | Steven L. Berk, Tennessee |

| ETSU-17 | Steven L. Berk, Tennessee |

| ETSU-5 | Steven L. Berk, Tennessee |

| B59911 | David Goldblatt, England |

| B59504 | David Goldblatt, England |

General DNA methods.

M. catarrhalis genomic DNA was isolated from agar plate-grown cells by using the Easy-DNA kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with minor modifications. The preparation of plasmids and purification of PCR products were performed using kits manufactured by QIAGEN (Santa Clarita, CA).

DNA sequencing and analysis.

The M. catarrhalis strain ATTC 43617 genome sequence was previously published (NCBI patent number WO0078968). This sequenced genome was scanned using Gene Tool (Biotools Inc.) in all open reading frames to search for proteins with homology to neisserial Opa protein sequences. The identified sequence was submitted to BLASTP (Entrez-PubMed) to examine it for homologous proteins. Where indicated, DNA fragments were sequenced by the York University DNA Sequencing Facility (http://www.biol.yorku.ca/cm/autoseq.htm), using the same primers. Mult-Alin (8) was used to generate sequence alignments. Two-dimensional (2D) and 3D modeling was performed using 3D-JIGSAW (3, 4, 6). Neighbor-joining tree diagrams were designed using ClustalW (http://clustalw.genome.jp/)-based sequence alignments and Phlyodraw v0.82.

Cloning the gene.

PCR primers Sgo114 (AACCCAATGCCACAAGGAC) and Sgo115 (AGCATTTGGACTGTGTGGG) were designed using the putative M. catarrhalis olpA gene identified on the basis of our analyses of the M. catarrhalis genome (NCBI patent number WO0078968). A PCR product was amplified using primers Sgo114 and Sgo115 from chromosomal DNAs of strains 035E, 046E, ATTC 25238, 7169, 4223, and TTA37 and then cloned into the pCC1 (Blunt Cloning-Ready) vector (Epicenter Biotechnologies) to create pCC.035E, pCC.046E, pCC.25238, pCC.7169, pCC.4223, and pCC.TTA37, respectively. A kanamycin resistance cassette was obtained and cloned into pCC1 to generate the pCCKan control. Plasmids were electroporated into electrocompetent TransforMax E. coli EPI300 as described in the Epicenter CopyControl cDNA, gene, and PCR cloning kit to create OlpA-expressing E. coli strains. The periplasmic maltose binding protein (MBP)-encoding plasmid pMAL was obtained from New England Biolabs and introduced into E. coli EPI300 by electroporation.

Preparation of polyclonal OlpA antiserum.

The translated OlpA protein sequence from M. catarrhalis strain O35E was analyzed for hydrophilic sequence stretches by using the Kyte-Doolittle method (20). The peptide SNLEAKYNDNRPNDNKLEDK was selected and synthesized, with a cysteine residue added to its N terminus, by the Protein Chemistry Technology Center at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. This peptide was covalently coupled to Imject maleimide-activated mariculture keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Pierce, Rockford, IL). A 100-μg portion of the peptide-keyhole limpet hemocyanin conjugate was mixed 50:50 with Freund's complete adjuvant (Difco, Detroit, MI) and used to immunize five BALB/c mice. Four weeks later, these mice received a booster immunization with 30 μg of this conjugate mixed 1:1 with Freund's incomplete adjuvant. These animals were euthanatized and exsanguinated approximately 2 weeks later, and serum was then prepared from this blood by standard methods.

Western blot analysis.

For detection of the OlpA protein, whole-cell lysates (1) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 12.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide separating gels, transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and probed with the indicated primary antibody. OlpA was detected using the mouse polyclonal OlpA antisera described herein. UspA1 and CopB were detected using the monoclonal antibodies 245B5 (7) and 10F3 (13), respectively. Maltose binding protein was detected using the MBP-specific monoclonal antibody (New England Biolabs). The FbpA-specific rabbit polyclonal antiserum was generously provided by Anthony Schryvers (University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada). The secondary antibody used was goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Antigen-antibody complexes were visualized by chemiluminescence by use of the Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA).

Protease treatment of intact cells.

M. catarrhalis or E. coli cells were grown in broth overnight at 37°C. Cells were pelleted and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM CaCl2 (PBS-Mg/Ca) and resuspended to a concentration of 1 × 109 cells/ml. Then, 250 μl of cells was incubated with increasing proteinase K (Pharmacia) before incubation at room temperature for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 μl of a 10-mg/ml stock of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (in isopropanol) to stop the reaction. The cells were then centrifuged and resuspended in PBS-Mg/Ca twice, and the final washed pellet was then boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol.

Heat modifiability.

Bacterial cultures were grown overnight at 37°C. Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were then incubated either at room temperature or in a boiling water bath for 20 min before Western blot analysis.

OMVs.

Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) of M. catarrhalis were isolated through heating in the presence of EDTA, as described by Murphy and Loeb (26). Briefly, 50 ml brain heart infusion broth was inoculated with M. catarrhalis and cultured overnight with shaking at 37°C. The cells were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and the resulting pellet then resuspended in 0.05 M Na2HPO4, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.01 M EDTA (pH 7.4) before incubation at 56°C with shaking. The bacteria were removed by two consecutive spins of 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C to recover the outer membrane vesicles, which were then resuspended in PBS.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The olpA sequences determined in this study were submitted via the Entrez-PubMed protein/nucleotide database, and accession numbers are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Accession numbers of olpA genes from strains used for cloning

RESULTS

Identification of OlpA.

Given the close relationship between M. catarrhalis and the Neisseria spp., we sought to determine whether proteins related to the neisserial Opa proteins are present in M. catarrhalis. A search of the M. catarrhalis ATCC 43617 genome was conducted using Gene Tool software by searching with a combination of neisserial Opa protein antigenic variants. The screen identified an open reading frame encoding a predicted protein with a high degree of sequence identity to neisserial Opa proteins. The predicted protein is 234 amino acids in length with a possible leader peptide of 30 amino acids. Oligonucleotide primers Sgo114 and Sgo115 (see Materials and Methods) were designed based on this predicted open reading frame and used to screen a variety of M. catarrhalis laboratory strains by PCR. A single fragment of ∼1.6 kb in size was amplified from each of the strains and then sequenced. GenBank accession numbers for each sequence are listed in Table 2. The various M. catarrhalis alleles encode proteins displaying a remarkably high level of sequence identity, with the most obvious difference being that strains 035E and 046E have a two-amino-acid (NT) insertion in the second predicted surface-exposed region (Fig. 1A and B). Besides this insertion, the sequences were almost 100% identical to each other, yet they diverge from the original sequence identified from the genome screen (compare sequence for ATTC 43617 in Fig. 1A). To distinguish the relatively high conservation of the M. catarrhalis proteins from the hypervariable nature of the neisserial Opa protein, we termed the former Opa-like protein A (OlpA).

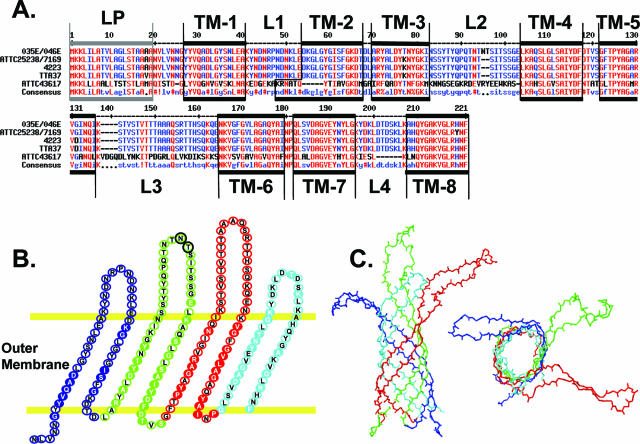

FIG. 1.

Moraxella catarrhalis OlpA. A. Alignment of OlpA proteins from M. catarrhalis strains ATTC4 3617, 035E, 046E, 4223, ATTC 25238, 7169, and TTA37. Red indicates high (>90%) conservation; blue indicates >50% conservation. !, I or V; $, indicates L or M; %, F or Y; #, any one of N, D, Q, or E. Gene sequence accession numbers are listed in Table 2. B. Predicted 2D structure of OlpA. Residues depicted in filled circles with white lettering are identical in OlpA and Neisseria NspA; those in black are unique to OlpA. The two-residue insertion in the second extracellular loops of M. catarrhalis strains O35E and O46E are encircled in black and green. C. Predicted OlpA 3D structure. The structure was derived by threading over the crystal structure of the neisserial NspA.

OlpA is a putative outer membrane protein.

Neisserial Opa proteins are outer membrane proteins containing eight antiparallel β-sheets connected by short (1- to 2-residue) periplasmic loops and larger (10- to 25-residue) variable surface-exposed loops. In addition to a relationship with the Opa proteins, BLASTp analysis revealed that OlpA also shares homology with various other outer membrane proteins, including the neisserial NspA. Comparisons of linear sequences and their respective predicted secondary and tertiary structures suggest that OlpA also forms a β-barrel structure within the outer membrane protein (Fig. 1B). This allowed a model of OlpA structure to be created by threading its sequence over that of NspA (Fig. 1C), which has recently been crystallized (31). This analysis revealed that OlpA possesses significantly larger surface-exposed loops than NspA, making them more reminiscent of the neisserial Opa proteins. The few differences between the sequences obtained in this study all lay within regions predicted to be surface exposed. Moreover, the strain ATTC 43617 genomic OlpA sequence divergence also lies primarily within the predicted surface-exposed regions.

Expression of OlpA.

To monitor expression of OlpA, we generated mouse polyclonal antiserum to an OlpA-derived peptide (see Materials and Methods). Immunoblot analysis indicated that this antiserum detected a 24-kDa protein expressed by a number of Moraxella strains (Fig. 2A), with the exception being the genome-sequenced strain ATTC 43617, which diverges within the sequence used in generation of the polyclonal antibody. A 1.6-kb PCR product containing the olpA gene from each M. catarrhalis strain was then cloned into the pCC1 copy control plasmid and expressed in E. coli strain EPI300, as outlined in Materials and Methods. E. coli cell lysates were probed with the polyclonal OlpA-specific antiserum to confirm that the recombinant protein was expressed in E. coli (Fig. 2B). The OlpA protein was expressed in E. coli without any induction, indicating that expression is likely constitutively driven by its native M. catarrhalis promoter (Fig. 2B and data not shown).

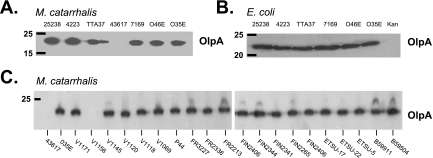

FIG. 2.

Detection of OlpA protein by immunoblotting. Western blots of bacterial lysates were probed with the OlpA-specific antiserum. A. M. catarrhalis cell lysates. B. Cell lysates from recombinant E. coli strains expressing either OlpA cloned from the indicated M. catarrhalis strains or a kanamycin cassette (Kan) as a negative control. C. Immunoblot analysis to detect reactivity with M. catarrhalis strain O35E-specific OlpA antiserum with lysates prepared from the indicated strains. Molecular mass position markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left.

Conservation of OlpA among M. catarrhalis strains.

Considering that the cloned olpA gene sequences were highly conserved among the M. catarrhalis strains tested in this study, it is remarkable that the strain ATTC 43617 genome sequence-derived allele is so distinct. Since the OlpA antiserum distinguishes between these two variants, we collected M. catarrhalis strains from a variety of geographic locations (Table 1) and probed bacterial lysates by immunoblotting. In total, 25 of the 27 strains tested during this study reacted with the M. catarrhalis antibody (Fig. 2A and C), with only strains ATTC 43617 and V1156 displaying no cross-reactive OlpA. To understand the relationship between these two proteins, we sequenced the V1156 allele. As expected, the V1156 OlpA (GenBank accession no. DQ996464) is closely related to that of ATTC 43617, suggesting that these two represent an uncommon second variant of OlpA.

Surface accessibility and heat modifiability.

Our structural analyses suggested that OlpA is a surface-exposed outer membrane protein (Fig. 1B and C). Consistent with its specificity for a peptide sequence predicted to lie within the transmembrane sequence (Fig. 1B), the OlpA-specific antiserum did not react with intact bacteria (data not shown). To localize the OlpA protein, M. catarrhalis strain 035E was treated with heat and EDTA to liberate OMVs (26). Immunoblot analysis confirmed that the OMV preparations contained OlpA and other well-characterized outer membrane proteins, including CopB and UspA1 (Fig. 3A), while the abundant periplasmic ferric binding protein (FbpA) was barely detectable (data not shown), consistent with an outer membrane localization of OlpA. To confirm exposure at the bacterial cell surface, whole-cell lysates from recombinant OlpA-expressing E. coli and M. catarrhalis that had been treated with proteinase K were subjected to immunoblot analysis. Protease treatment caused a dose-dependent degradation of OlpA without affecting the integrity of the periplasmic maltose binding protein (MbpA) or FbpA (Fig. 3B), confirming surface exposure of OlpA.

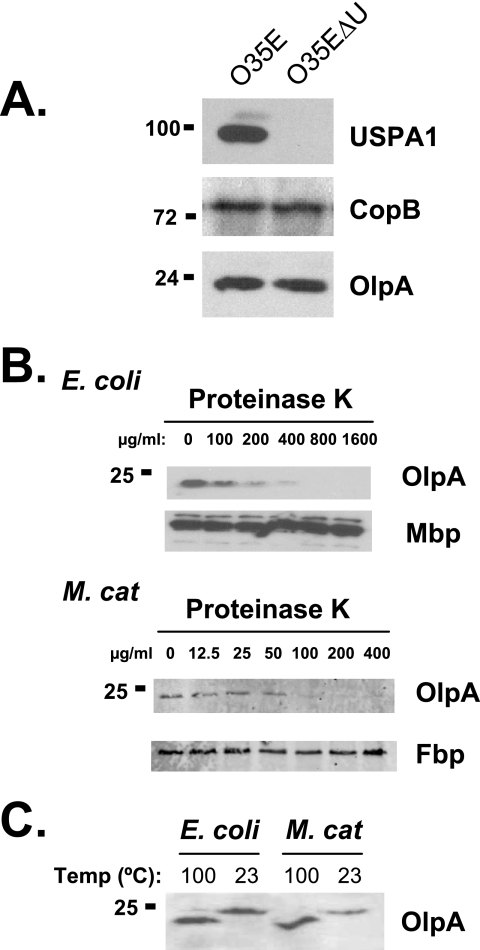

FIG. 3.

A. Detection of OlpA in EDTA-induced outer membrane vesicles of M. catarrhalis. OMVs prepared from either strain O35E or the USPA1-deficient 035E mutant (O35EΔU) were probed with specific antibodies to detect OlpA, USPA1, and CopB. B. Surface exposure of OlpA. Intact E. coli expressing either OlpA or the periplasmic MBP were subjected to increasing doses of trypsin and proteinase K. Lysates were resolved and probed for either OlpA or MBP, as indicated. C. Heat-modifiability of OlpA was detected by using SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis following incubation of bacterial cell lysates for 20 min at either 100°C or 23°C. Molecular mass position markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left.

The β-barrel structure of many gram-negative outer membrane proteins, including the neisserial Opa proteins, tends to resist unfolding in SDS-containing sample buffer unless they are boiled. The electrophoretic mobility of OlpA was affected by heating (Fig. 3C), consistent with a β-barrel conformation. The heat-modifiable nature of recombinant OlpA expressed in E. coli is indistinguishable from that observed in the respective M. catarrhalis strains, suggesting that the expression and folding of OlpA in E. coli are comparable to those of its native form.

M. catarrhalis OlpA does not bind to CEACAM receptors.

The M. catarrhalis UspA1 protein attaches to human CEACAM receptors (15). Given the similarity between OlpA and the neisserial Opa proteins, we sought to determine whether these Opa homologues might represent another mechanism by which M. catarrhalis binds to CEACAM and/or other host receptors. E. coli expressing the OlpA from strain 046E or ATTC 25238 did not interact with either soluble CEACAM1 or CEACAM5 in either bacterial pull-down or solid-phase binding assays, while E. coli expressing the Neisseria gonorrhoeae Opa57 protein bound both proteins (data not shown). Moreover, a UspA1-deficient derivative of M. catarrhalis 035E does not bind to CEACAM-expressing cell lines (data not shown) despite expressing OlpA (Fig. 2 and 3). We were also unable to detect any difference in heparin binding between the recombinant OlpA-expressing E. coli and the parental strain, suggesting that OlpA does not function as a heparan sulfate proteoglycan-specific adhesin in a manner similar to the related N. gonorrhoeae Opa50 (32), the Neisseria meningitidis OpcA (34), or the enterotoxigenic E. coli Tia protein (11). To ascertain whether any adhesin function could be attributed to OlpA in M. catarrhalis, we generated an olpA-deficient strain of M. catarrhalis O35E by insertional mutagenesis. Next, we performed in vitro infection assays to compare wild-type, UspA1-deficient, and OlpA-deficient M. catarrhalis 035E, as well as the OlpA-expressing versus parental (empty expression vector-containing) E. coli strains. These studies provided no evidence that OlpA facilitates bacterial association with HeLa (human endocervical), A549 (human lung-derived), Caco-2 (human colon-derived), or Lec11 (Chinese hamster ovary-derived) cell lines, in either the presence or absence of serum (data not shown).

Homologues.

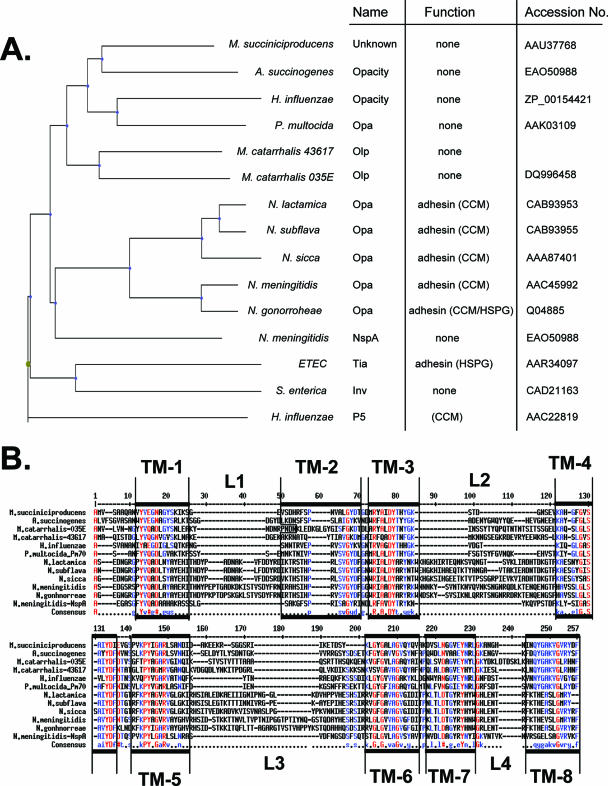

Considering the presence of the OlpA in M. catarrhalis and the presence of the closely related Opa and NspA proteins in Neisseria spp., we next sought to determine the phylogenetic distribution of Opa-like proteins via mining of available genome sequences. Interestingly, H. influenzae, which also exclusively colonizes the human upper respiratory tract and causes a localized and disseminated infection, encodes a protein that has significant sequence identity to OlpA but otherwise remains uncharacterized (accession no. ZP_00154421) (Fig. 4). Other respiratory pathogens, such as Actinobacillus succinogenes and Pasteurella multocida, also appear to have highly related homologues (Fig. 4). Each of these Opa-like proteins is more closely related to the M. catarrhalis OlpA than to the neisserial Opa proteins (Fig. 4A). Related proteins are also evident in the Enterobacteriaceae, including a homologue present in enterotoxigenic E. coli that functions as an adhesin involved in pathogenesis (11).

FIG. 4.

Relationship between diverse Opa-like proteins. A. The neighbor-joining tree diagram depicted is based on ClustalW protein alignments using Phylodraw, as outlined in Materials and Methods. Listed are bacterial species, previously used names and functions of OlpA-related proteins, and sequence accession numbers. ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli. B. Sequence alignment of diverse Opa-like proteins representing the indicated bacterial species illustrated in the tree diagram (A). Predicted surface loops are indicated as L1 to L4, while transmembrane regions are indicated by TM1 to TM8. Amino acid sequence identities are indicated by red (>90%) or blue (>50%).

DISCUSSION

In searching for homologues of the well-characterized Opa protein adhesins from the pathogenic Neisseria spp., we have identified a previously uncharacterized but highly conserved outer membrane protein in M. catarrhalis. While the OlpA protein shares a high degree of similarity with neisserial Opa proteins, we found no evidence that they share a similar function. While neisserial Opa proteins bind to CEACAM and/or HSPG receptors (12, 32, 33), neither OlpA-expressing but UspA1-deficient M. catarrhalis nor the OlpA-expressing E. coli displayed any binding to either of these receptor types. In fact, we did not detect OlpA-mediated adherence to any of a variety of cell lines tested here.

Sequence alignments and our experimental results described here indicate that OlpA forms an eight-stranded β-barrel in the M. catarrhalis outer membrane. This allowed us to predict the 3D structure by threading over the closely related N. meningitidis NspA, which has been previously crystallized (31). Curiously, the OlpA proteins appear to have surface-exposed loops that are much larger than those of NspA yet shorter than those found in the Opa adhesins. The similarity of OlpA to the well-characterized NspA and Opa proteins make it very likely that these structural predictions provide an accurate depiction of OlpA in the membrane-spanning regions. However, the software used cannot predict the tertiary structure within the surface-exposed loops.

While the search for a vaccine protecting against M. catarrhalis infection has led to the characterization of other outer membrane proteins, this is the first description of OlpA. To ensure that the OlpA gene is expressed, we generated an antibody against a peptide in the predicted OlpA gene and detected expression in M. catarrhalis strains and recombinant E. coli in which the gene is being expressed from its native promoter. We also confirmed that OlpA was present within outer membrane fractions, had a heat-modifiable native structure characteristic of β barrel structures, and was surface exposed.

The level of conservation within the OlpA genes sequenced was remarkably high, with only two different variants apparent among the 27 strains tests. Of note, these variants are highly conserved among membrane-spanning sequences, with significant deviation apparent only within the surface-exposed loops. However, 25 of 27 strains contained the variant typified by strain 035E, with >99% identity among the six sequenced alleles.

Considering the lack of CEACAM and HSPG binding and the relatively high conservation of OlpA compared to neisserial Opa proteins, we wondered whether similar proteins exist in more distantly related bacterial species. Our survey of available genome sequences indicates that there are uncharacterized outer membrane proteins with a high degree of similarity to OlpA in a wide variety of species (Fig. 4). Our alignments indicate that each of these is an outer membrane protein with eight antiparallel β-strands and four surfaced-exposed loops, and some species contain homologues in two different genomic loci. As with the M. catarrhalis OlpA variants, these homologues possess high sequence conservation within the transmembrane sequences but vary in size and linear sequence within the surface-exposed loops. It will be interesting to establish whether the strict conservation of certain residues within the membrane-spanning sequences reveals residues that are required for proper folding or membrane insertion of the basic eight-stranded β-barrel structure versus those that are evolutionarily related.

While the function of OlpA proteins remains unknown, their conservation across phylogenetically disparate bacterial species suggests a basic essential function. This, along with the fact that the M. catarrhalis OlpA protein is surface exposed and highly conserved, makes it an obvious vaccine candidate. Finally, when considering the evolutionary relationship among the Opa and Opa-like proteins, it is enticing to speculate that evolution has taken advantage of the minimal β-barrel structure represented by proteins such as NspA to provide a basic framework on which host cell binding adhesins or proteins possessing other necessary functions can be derived.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from Canadian Institutes for Health research grant no. MOP-15499 to S.D.G.-O. and U.S. Public Health Service grant no. AI36344 to E.J.H. S.D.G. is supported by New Investigator Awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and is a recipient of the Province of Ontario Premier's Research Excellence Award.

We thank John Nelson, Anthony Campagnari, David Goldblatt, Richard Wallace, Steven Berk, Merja Helminen, and Frederick Henderson for providing the wild-type isolates of M. catarrhalis and Anthony B. Schryvers for the FbpA-specific antiserum used in this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aebi, C., I. Maciver, J. L. Latimer, L. D. Cope, M. K. Stevens, S. E. Thomas, G. H. McCracken, Jr., and E. J. Hansen. 1997. A protective epitope of Moraxella catarrhalis is encoded by two different genes. Infect. Immun. 65:4367-4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandak, S. I., M. R. Turnak, B. S. Allen, L. D. Bolzon, D. A. Preston, S. K. Bouchillon, and D. J. Hoban. 2001. Antibiotic susceptibilities among recent clinical isolates of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis from fifteen countries. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates, P. A., L. A. Kelley, R. M. MacCallum, and M. J. Sternberg. 2001. Enhancement of protein modeling by human intervention in applying the automatic programs 3D-JIGSAW and 3D-PSSM. Proteins 5(Suppl.):39-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates, P. A., and M. J. Sternberg. 1999. Model building by comparison at CASP3: using expert knowledge and computer automation. Proteins 3(Suppl.):47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen, J. J. 1999. Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis: clinical, microbiological and immunological features in lower respiratory tract infections. APMIS 88(Suppl.):1-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Contreras-Moreira, B., and P. A. Bates. 2002. Domain fishing: a first step in protein comparative modelling. Bioinformatics 18:1141-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cope, L. D., E. R. Lafontaine, C. A. Slaughter, C. A. J. Hasemann, C. Aebi, F. W. Henderson, G. H. J. McCracken, and E. J. Hansen. 1999. Characterization of the Moraxella catarrhalis uspA1 and uspA2 genes and their encoded products. J. Bacteriol. 181:4026-4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corpet, F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:10881-10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig, L., M. E. Pique, and J. A. Tainer. 2004. Type IV pilus structure and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:363-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faden, H., J. Hong, and T. Murphy. 1992. Immune response to outer membrane antigens of Moraxella catarrhalis in children with otitis media. Infect. Immun. 60:3824-3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleckenstein, J. M., J. T. Holland, and D. L. Hasty. 2002. Interaction of an outer membrane protein of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli with cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Infect. Immun. 70:1530-1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray-Owen, S. D., C. Dehio, A. Haude, F. Grunert, and T. F. Meyer. 1997. CD66 carcinoembryonic antigens mediate interactions between Opa-expressing Neisseria gonorrhoeae and human polymorphonuclear phagocytes. EMBO J. 16:3435-3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helminen, M. E., I. Maciver, J. L. Latimer, L. D. Cope, G. H. McCracken, Jr., and E. J. Hansen. 1993. A major outer membrane protein of Moraxella catarrhalis is a target for antibodies that enhance pulmonary clearance of the pathogen in an animal model. Infect. Immun. 61:2003-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill, D. J., M. A. Toleman, D. J. Evans, S. Villullas, L. Van Alphen, and M. Virji. 2001. The variable P5 proteins of typeable and non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae target human CEACAM1. Mol. Microbiol. 39:850-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill, D. J., and M. Virji. 2003. A novel cell-binding mechanism of Moraxella catarrhalis ubiquitous surface protein UspA: specific targeting of the N-domain of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules by UspA1. Mol. Microbiol. 48:117-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holm, M. M., S. L. Vanlerberg, I. M. Foley, D. D. Sledjeski, and E. R. Lafontaine. 2004. The Moraxella catarrhalis porin-like outer membrane protein CD is an adhesin for human lung cells. Infect. Immun. 72:1906-1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm, M. M., S. L. Vanlerberg, D. D. Sledjeski, and E. R. Lafontaine. 2003. The Hag protein of Moraxella catarrhalis strain O35E is associated with adherence to human lung and middle ear cells. Infect. Immun. 71:4977-4984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karalus, R., and A. Campagnari. 2000. Moraxella catarrhalis: a review of an important human mucosal pathogen. Microbes Infect. 2:547-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyd, J. M., A. W. Cripps, and T. F. Murphy. 1998. Outer-membrane antigen expression by Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis influences pulmonary clearance. J. Med. Microbiol. 47:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyte, J., and R. F. Doolittle. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157:105-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lafontaine, E. R., L. D. Cope, C. Aebi, J. L. Latimer, G. H. McCracken, Jr., and E. J. Hansen. 2000. The UspA1 protein and a second type of UspA2 protein mediate adherence of Moraxella catarrhalis to human epithelial cells in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 182:1364-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luke, N. R., and A. A. Campagnari. 1999. Construction and characterization of Moraxella catarrhalis mutants defective in expression of transferrin receptors. Infect. Immun. 67:5815-5819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luke, N. R., A. J. Howlett, J. Shao, and A. A. Campagnari. 2004. Expression of type IV pili by Moraxella catarrhalis is essential for natural competence and is affected by iron limitation. Infect. Immun. 72:6262-6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy, T. F. 1996. Branhamella catarrhalis: epidemiology, surface antigenic structure, and immune response. Microbiol. Rev. 60:267-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy, T. F., A. L. Brauer, B. J. Grant, and S. Sethi. 2005. Moraxella catarrhalis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: burden of disease and immune response. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172:195-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy, T. F., and M. R. Loeb. 1989. Isolation of the outer membrane of Branhamella catarrhalis. Microb. Pathog. 6:159-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy, T. F., and S. Sethi. 1992. Bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 146:1067-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy, T. F., and S. Sethi. 1997. A national strategy for research in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA 277:1596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toleman, M., E. Aho, and M. Virji. 2001. Expression of pathogen-like Opa adhesins in commensal Neisseria: genetic and functional analysis. Cell. Microbiol. 3:33-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turnak, M. R., S. I. Bandak, S. K. Bouchillon, B. S. Allen, and D. J. Hoban. 2001. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of clinical isolates of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis collected during 1999-2000 from 13 countries. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:671-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vandeputte-Rutten, L., M. P. Bos, J. Tommassen, and P. Gros. 2003. Crystal structure of neisserial surface protein A (NspA), a conserved outer membrane protein with vaccine potential. J. Biol. Chem. 278:24825-24830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Putten, J. P., and S. M. Paul. 1995. Binding of syndecan-like cell surface proteoglycan receptors is required for Neisseria gonorrhoeae entry into human mucosal cells. EMBO J. 14:2144-2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virji, M., K. Makepeace, D. J. P. Ferguson, and S. Watt. 1996. Carcinoembryonic antigens (CD66) on epithelial cells and neutrophils are receptors for Opa proteins of pathogenic neisseriae. Mol. Microbiol. 22:941-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Virji, M., K. Makepeace, I. R. A. Peak, D. J. P. Ferguson, M. P. Jennings, and E. R. Moxon. 1995. Opc- and pilus-dependent interactions of meningococci with human endothelial cells: molecular mechanisms and modulation by surface polysaccharides. Mol. Microbiol. 18:741-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virji, M., S. Watt, K. Barker, K. Makepeace, and R. Doyonnas. 1996. The N-domain of the human CD66a adhesion molecule is a target for Opa proteins of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 22:929-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]