Abstract

Expression of the inner membrane protein FoxB (PA2465) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mutants of Sinorhizobium meliloti that are defective in the utilization of ferrichrome, ferrioxamine B, and schizokinen resulted in the restoration of siderophore utilization. Mutagenesis of foxB in P. aeruginosa did not abolish siderophore utilization, suggesting that the function is redundant.

Virtually all organisms display an absolute requirement for iron. Although iron is the fourth most abundant element on earth, it is rapidly oxidized and at neutral pH is virtually insoluble. Pathogens encounter conditions of iron limitation within infected tissues due to the action of iron binding proteins such as transferrin and lactoferrin that serve to prevent an infection from developing (9, 24, 25). To overcome these conditions of iron limitation, many bacteria synthesize high-affinity chelators termed siderophores that serve to deliver iron to the cell.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa occupies a diverse range of ecological niches, including soil and water habitats, and is a versatile opportunistic pathogen capable of infecting a range of eukaryotic species including animals, insects, and plants. Under iron-limiting conditions, P. aeruginosa produces two siderophores, pyoverdine and pyochelin, that have been shown to contribute to the virulence of the organism (8, 26). P. aeruginosa is predicted to encode up to 34 putative TonB-dependent receptors, many of whose ligands have not yet been characterized (7). Predictably, the organism has been shown to be capable of utilizing a wide range of xenosiderophores, including ferrichrome (17, 22), ferrioxamine B (3, 17, 19, 22), rhizobactin 1021, schizokinen, and aerobactin (16, 22). The number of siderophore receptors may explain the phenomenon of transport redundancy with multiple receptors capable of recognizing and transporting a particular siderophore. In contrast, there are few readily identifiable inner membrane siderophore transport systems relative to the predicted number of receptors (13, 21, 23). We report here the identification of the protein FoxB that functions in the utilization of ferrichrome, ferrioxamine B, and schizokinen across the inner membrane by a redundant mechanism.

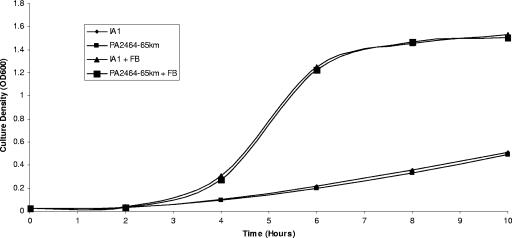

Recently, the outer membrane receptors for ferrioxamine B and ferrichrome, FoxA (PA2466) and FiuA (PA4070), respectively, were identified (3, 17). By in silico analysis, a putative transporter and a protein of unknown function, encoded by foxB (PA2465) and PA2464, respectively, which are located directly downstream of foxA, were identified. To investigate the possible role of FoxB and PA2464 in ferrioxamine B utilization, both genes were deleted and replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette by allelic replacement in the pyoverdine and pyochelin biosynthesis mutant P. aeruginosa IA1 (2). Growth promotion assays of the resultant mutant P. aeruginosa PA2464-65km indicated that growth was indistinguishable from that of the parent strain when bacteria were grown under iron-limiting conditions in the presence of ferrioxamine B (Fig. 1). Analysis by the siderophore utilization bioassay confirmed that P. aeruginosa PA2464-65km was unaffected in the utilization of ferrioxamine B and that the utilization of ferrichrome, rhizobactin 1021, schizokinen, and aerobactin was similarly unaffected compared to that by P. aeruginosa IA1 (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Growth promotion analysis of P. aeruginosa IA1 and PA2464-65km in response to iron limitation and ferrioxamine B. Cultures were supplemented with 2,2′-dipyridyl (500 μM) and ferrioxamine B (FB; 1 μM), as appropriate. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of the role of FoxB in siderophore utilization

| Strain | Genotype | Plasmid | Ferrichrome | Ferrioxamine B | Schizokinen | Rhizobactin 1021 | Aerobactin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa IA1 | pvd pch | + | + | + | + | + | |

| P. aeruginosa PA2464-65km | pvd pch PA2464 foxB | + | + | + | + | + | |

| S. meliloti 2011 | Wild type | + | + | + | + | NTa | |

| S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3 | rhtX | + | + | − | − | NT | |

| S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3 | rhtX | pOC2465 | + | + | + | − | NT |

| S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3hmuU-Tn5lac | rhtX hmuU | − | − | − | − | NT | |

| S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3hmuU-Tn5lac | rhtX hmuU | pOC2465 | + | + | + | − | NT |

| S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3smc01659km | rhtX smc01659 | − | − | − | − | NT | |

| S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3smc01659km | rhtX smc01659 | pOC2465 | + | + | + | − | NT |

NT, not tested.

Previously we identified a novel protein, RhtX, functioning in the utilization of rhizobactin 1021 and schizokinen by Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011 (18, 21). To investigate the possible role of PA2464 and FoxB in rhizobactin 1021 and schizokinen utilization, a mutant was constructed by the insertion of an Ω-chloramphenicol resistance cassette in rhtX by allelic exchange generating S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3. S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3 is unable to utilize rhizobactin 1021 or schizokinen and also does not synthesize rhizobactin 1021. The ability of PA2464 and foxB to complement S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3 was examined. PA2464 and foxB were PCR amplified with their own ribosome binding sites, individually and collectively, and cloned into the broad-host-range vector pBBR1MCS-5, placing them under the control of the vector-borne lac promoter (14). The resulting plasmids facilitate inducible expression of PA2464 and foxB individually (pOC2464 and pOC2465, respectively) and in combination (pOC2464-65). Siderophore bioassay analysis indicated that FoxB alone was sufficient to confer upon S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3 the ability to utilize schizokinen but not the structurally similar siderophore rhizobactin 1021 (Table 1).

S. meliloti 2011 is capable of utilizing both ferrichrome and ferrioxamine B to satisfy its iron requirements (20, 21). We have determined that the utilization of ferrichrome and ferrioxamine B across the inner membrane of S. meliloti 2011 is mediated by an ABC transport system comprising the periplasmic binding protein Smc01659, the inner membrane permease Smc01511 (hmuU), and the ATPase Smc01510 (hmuV) (P. Ó Cuív and M. O'Connell, unpublished data). Mutants with insertions in smc01659, smc01510, and smc01511, generated in an S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3 background, are defective in ferrichrome and ferrioxamine B utilization. The mutants were complemented, however, by pOC2465, further suggesting that FoxB functions in siderophore utilization (Table 1). It was noticeable that ferrichrome utilization was weaker than that of ferrioxamine B compared to utilization by S. meliloti 2011rhtX-3, suggesting that FoxB possibly has a greater specificity for the latter siderophore (data not shown).

In Escherichia coli, the utilization of hydroxamate siderophores across the inner membrane is dependent on the FhuCDB transport system. The ability of PA2464 and foxB to complement a fhuB mutant, E. coli B1713, was examined. E. coli B1713 is a derivative of E. coli K-12 that is defective in enterobactin biosynthesis and that carries a λplacMu insertion in fhuB. Neither PA2464 nor FoxB, individually or in combination, conferred upon E. coli B1713 the ability to utilize ferrichrome (Table 1). E. coli K-12 does not encode high-affinity outer membrane receptors for ferrioxamine B or rhizobactin 1021, schizokinen, and aerobactin, and there is no observable utilization of these siderophores as determined by siderophore bioassay analysis. Consequently, to further analyze the utilization of these siderophores the ferrioxamine B outer membrane receptor foxA from Yersinia enterocolitica (4) and the rhizobactin 1021, schizokinen, and aerobactin outer membrane receptor iutA from the E. coli virulence plasmid pColV-K311 (10, 21) were expressed in trans. The introduction of pOC2464, pOC2465, and pOC2464-65 did not confer upon E. coli B1713 expressing foxA the ability to utilize ferrioxamine B (data not shown). Similarly, the introduction of pOC2464, pOC2465, and pOC2464-65 did not confer upon E. coli B1713 expressing iutA the ability to utilize rhizobactin 1021, schizokinen, or aerobactin (data not shown).

FoxB is predicted to be 382 amino acids in length with a molecular mass of 43 kDa. The protein is predicted to be localized to the inner membrane, and the ability of FoxB to facilitate siderophore utilization in S. meliloti 2011 inner membrane siderophore transport mutants supports this prediction. FoxB is predicted to have eight transmembrane segments as determined by TMPred analysis (www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html). A PepSY_TM transmembrane helix (PF03929) was identified in the FoxB amino acid sequence by using the Pfam database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/). The PepSY_TM transmembrane helices are commonly found bounding a PepSY domain and serve to hold the domain to the exterior of the cell (27). The FoxB sequence was used to identify corresponding protein homologues in the GenBank database by using the BLASTP program (1). The highest percentages of identity to FoxB were those of PaerC_01001425 from P. aeruginosa C3719 (99%), Paer03000003 from P. aeruginosa UCBPP-PA14 (99%), PaerP_01005749 from P. aeruginosa PA7 (98%), Pfl_0120 from Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 (67%), and PFL_0124 from P. fluorescens Pf-5 (66%). In all instances, the FoxB homologues are encoded in propinquity to putative siderophore outer membrane receptors. Recently, Benson et al. (5) reported the discovery of FegB, a novel transporter from Bradyrhizobium japonicum that functions in ferrichrome utilization. Although FegB displays limited identity to FoxB (19%), in silico analysis suggests that it also possesses eight transmembrane segments and a PepSY_TM helix (5; Ó Cuív and O'Connell, unpublished data).

Our results suggest that transport by P. aeruginosa of ferrichrome, ferrioxamine B, and schizokinen across the inner membrane is by a redundant mechanism. Inner membrane redundancy possibly explains the difficulty in identifying inner membrane transport systems in P. aeruginosa by traditional techniques such as transposon mutagenesis. In addition, despite overlapping ligand specificities, FoxB, FegB, and RhtX display limited identity to each other, suggesting that siderophore transporters may exhibit significant sequence diversity but possess common ligand specificities. Thus, it may be difficult to identify unusual siderophore transport proteins and to predict their ligand specificities by in silico analysis alone. A possible mechanism for the identification of single-unit inner membrane transport systems is by high-throughput complementation of a heterologous host(s). It would be relatively straightforward to construct a broad-host-range mobilizable expression vector that could be used to identify novel siderophore transporters by complementation of a heterologous host(s).

The virulence of P. aeruginosa has been found to correlate to its ability to acquire iron, and consequently siderophores have attracted attention as a means of delivering antimicrobials by a “Trojan horse” mechanism, thereby overcoming antibiotic efflux systems (6, 11, 12, 15). The discovery that inner and outer membrane transport of ferrioxamine B and ferrichrome is redundant is particularly interesting as it suggests that it would be difficult for a mutation to arise that would abolish utilization. This makes both siderophores attractive as scaffolds for the generation of siderophore-antibiotic conjugates. Mutations affecting siderophore uptake would likely be in a gene(s) encoding a component common to all siderophore transport systems such as the tonB gene and would likely result in a weakened strain because of pleiotropic effects.

Little is known about inner membrane siderophore transport in P. aeruginosa, and the identification of FoxB further augments our knowledge of this process. To date, the only characterized inner membrane siderophore transport protein identified in P. aeruginosa is FptX, which functions in pyochelin utilization (21). FoxB is the first characterized member of a novel family of proteins that functions in siderophore utilization and only the second inner membrane siderophore transporter to be identified in P. aeruginosa. The mechanism of function of the FoxB family remains to be determined. However, the inability of FoxB to mediate siderophore utilization in E. coli suggests a possible requirement for an additional transport protein(s) or a limited ability to respond to chemiosmotic transport gradients, and this remains to be elucidated. It also remains to be determined whether FoxB functions in the transport of or in the release of iron from the siderophores. From in silico analysis, several additional uncharacterized transporters can be readily identified that are encoded in the immediate vicinity of predicted outer membrane siderophore receptors in P. aeruginosa. It will be of interest to determine if these transporters function in siderophore utilization and if they represent the general mechanism for inner membrane siderophore transport by P. aeruginosa.

Acknowledgments

This publication has emanated from research conducted with the financial support of the Science Foundation Ireland and Enterprise Ireland.

We thank colleagues who sent strains and plasmids.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ankenbauer, R., S. Sriyosachati, and C. D. Cox. 1985. Effects of siderophores on the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in human serum and transferrin. Infect. Immun. 49:132-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banin, E., M. L. Vasil, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:11076-11081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bäumler, A. J., and K. Hantke. 1992. Ferrioxamine uptake in Yersinia enterocolitica: characterization of the receptor protein FoxA. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1309-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson, H. P., E. Boncompagni, and M. L. Guerinot. 2005. An iron uptake operon required for proper nodule development in the Bradyrhizobium japonicum-soybean symbiosis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 18:950-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budzikiewicz, H. 2001. Siderophore-antibiotic conjugates used as Trojan horses against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 1:73-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelis, P., and S. Matthijs. 2002. Diversity of siderophore-mediated iron uptake systems in fluorescent pseudomonads: not only pyoverdines. Environ. Microbiol. 4:787-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, C. D. 1982. Effect of pyochelin on the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 36:17-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crosa, J. H. 1997. Signal transduction and transcriptional and posttranscriptional control of iron-regulated genes in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:319-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross, R., F. Engelbrecht, and V. Braun. 1985. Identification of the genes and their polypeptide products responsible for aerobactin synthesis by pColV plasmids. Mol. Gen. Genet. 201:204-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinisch, L., S. Wittmann, T. Stoiber, I. Scherlitz-Hofmann, D. Ankel-Fuchs, and U. Mollmann. 2003. Synthesis and biological activity of tris- and tetrakiscatecholate siderophores based on poly-aza alkanoic acids or alkylbenzoic acids and their conjugates with beta-lactam antibiotics. Arzneimittelforschung 53:188-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kline, T., M. Fromhold, T. E. McKennon, S. Cai, J. Treiberg, N. Ihle, D. Sherman, W. Schwan, M. J. Hickey, P. Warrener, P. R. Witte, L. L. Brody, L. Goltry, L. M. Barker, S. U. Anderson, S. K. Tanaka, R. M. Shawar, L. Y. Nguyen, M. Langhorne, A. Bigelow, L. Embuscado, and E. Naeemi. 2000. Antimicrobial effects of novel siderophores linked to beta-lactam antibiotics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 8:73-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Köster, W. 2001. ABC transporter-mediated uptake of iron, siderophores, heme and vitamin B12. Res. Microbiol. 152:291-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labaer, J., Q. Qiu, A. Anumanthan, W. Mar, D. Zuo, T. V. Murthy, H. Taycher, A. Halleck, E. Hainsworth, S. Lory, and L. Brizuela. 2004. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 gene collection. Genome Res. 14:2190-2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, P. V., and F. Shokrani. 1978. Biological activities of pyochelins: iron-chelating agents of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 22:878-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llamas, M. A., M. Sparrius, R. Kloet, C. R. Jimenez, C. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and W. Bitter. 2006. The heterologous siderophores ferrioxamine B and ferrichrome activate signaling pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 188:1882-1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch, D., J. O'Brien, T. Welch, P. Clarke, P. Ó. Cuív, J. H. Crosa, and M. O'Connell. 2001. Genetic organization of the region encoding regulation biosynthesis and transport of rhizobactin 1021, a siderophore produced by Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 183:2576-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer, J. M. 1992. Exogenous siderophore-mediated iron uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: possible involvement of porin OprF in iron translocation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:951-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noya, F., A. Arias, and E. Fabiano. 1997. Heme compounds as iron sources for nonpathogenic Rhizobium bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 179:3076-3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ó Cuív, P., P. Clarke, D. Lynch, and M. O'Connell. 2004. Identification of rhtX and fptX, novel genes encoding proteins that show homology and function in the utilization of the siderophores rhizobactin 1021 by Sinorhizobium meliloti and pyochelin by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, respectively. J. Bacteriol. 186:2996-3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ó Cuív, P., P. Clarke, and M. O'Connell. 2006. Identification and characterization of an iron-regulated gene, chtA, required for the utilization of the xenosiderophores aerobactin, rhizobactin 1021 and schizokinen by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 152:945-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole, K., and G. A. McKay. 2003. Iron acquisition and its control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: many roads lead to Rome. Front. Biosci. 8:d661-d686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratledge, C., and L. G. Dover. 2000. Iron metabolism in pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:881-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaible, U. E., and S. H. Kaufmann. 2004. Iron and microbial infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:946-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takase, H., H. Nitanai, K. Hoshino, and T. Otani. 2000. Impact of siderophore production on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in immunosuppressed mice. Infect. Immun. 68:1834-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeats, C., N. D. Rawlings, and A. Bateman. 2004. The PepSY domain: a regulator of peptidase activity in the microbial environment. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:169-172. [DOI] [PubMed]