Abstract

FCT region genes of Streptococcus pyogenes encode surface proteins that include fibronectin- and collagen-binding proteins and the serological markers known as T antigens, some of which give rise to pilus-like appendages. It remains to be established whether FCT region surface proteins contribute to virulence by in vivo models of infection. In this study, a highly sensitive and ecologically relevant humanized mouse model was used to measure superficial skin infection. Three genes encoding FCT region surface proteins essential for T-serotype specificity were inactivated. Both the Δcpa and ΔprtF2 mutants were highly attenuated for virulence when topically applied to the skin following exponential growth but were fully virulent when delivered in stationary phase. In contrast, the ΔfctA mutant was virulent at the skin, regardless of its initial growth state. Immunoblots of cell extracts revealed anti-FctA-reactive, ladder-like polymers characteristic of streptococcal pili. In addition, FctA formed a heteropolymer with the putative collagen-binding protein Cpa. The ΔfctA mutant showed a loss in anti-Cpa-reactive polymers, whereas anti-FctA-reactive polymers were reduced in the Δcpa mutant. The findings suggest that both FctA and Cpa are required for pilus formation, but importantly, an intact pilus is not essential for Cpa-mediated virulence. Although it is an integral part of the T-antigen complex, the fibronectin-binding protein PrtF2 is not covalently linked to the FctA- and Cpa-containing heteropolymer derived from cell extracts. The data provide direct evidence that streptococcal T antigens function as virulence factors in vivo, but they also reveal that a pilus-like structure is not essential for the most common form of streptococcal skin disease.

Pili can function to mediate bacterial adherence to host surfaces and facilitate horizontal gene transfer (14, 31, 43). Although well studied among many gram-negative organisms, pilus-like surface structures are becoming increasingly recognized as a component of gram-positive bacteria (26, 42, 45). Included among pilus-bearing bacteria are at least three species of Streptococcus that are important human pathogens (3, 23, 24, 28).

Genes encoding pilus-associated proteins map to the FCT region of Streptococcus pyogenes (28), a highly diversified portion of the genome that contains several well-studied genes (cpa, prtF1, and prtF2) encoding microbial surface cell recognition adhesion matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) (5, 12, 21, 32). The gene encoding the T6 antigen, which is an antigenic target of a major serological typing scheme, maps to the FCT regions of some isolates, where it forms part of the pilus structure (5, 28, 34). The T6 protein and other FCT region gene products are anchored to the peptidoglycan cell wall via specialized sortases, whose genes also lie within the FCT region (1, 2). Some isolates of S. pneumoniae have a genomic region, called a pathogenicity islet, that is similar in its general layout to the FCT region of S. pyogenes (16, 40); at least two of these pneumococcal gene products are incorporated into pilus structures (3, 24).

The functional role of FCT region-encoded surface proteins in virulence and the role of T antigens in particular have not been well studied using in vivo models of streptococcal disease. In this study, the nucleotide sequence for the complete FCT region of an impetigo isolate bearing the T3/13/B serotype, which is one of the most widely recognized T types in a recent survey of ∼40,000 isolates (19), was determined. The molecular relationships between FCT region surface proteins, pilus-like structures, and T antigens were characterized in depth, and the contributions of three FCT region-encoded surface proteins to virulence were evaluated in an animal model for superficial infection at the skin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial culture.

Unless otherwise specified, S. pyogenes was grown at 37°C in enriched broth medium consisting of Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 1% yeast extract (THY broth). Bacterial growth was monitored by optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Strain ALAB49 was recovered from an impetiginous skin lesion of a patient in Alabama in 1987 and is emm type 53.

Nucleotide sequence determination.

The nucleotide sequence of the FCT region was determined according to previously described methods (5), using an approach that involved long overlapping PCR fragments and primer walking. The sequencing strategy included strands in both directions and resulted in at least twofold coverage for all regions. Contigs were assembled and sequences analyzed for open reading frames (ORFs) by using Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, WI).

T agglutination test.

The T agglutination test was performed following trypsin treatment of whole bacteria, as described previously (18).

Construction of mutants.

Inactivation of FCT region genes was accomplished following transformation of wild-type (wt) strain ALAB49 with a linear DNA cassette containing the kanamycin resistance gene (aphA3) flanked by FCT region sequences that correspond to the upstream and downstream sequences of the gene targeted for inactivation. Linear DNA cassettes were constructed by a PCR-based assembly method (36). Individual oligonucleotide primers that are homologous to the ends of both the aphA3 gene and the corresponding flanking sequence were used to facilitate fusion of PCR products; primers are listed in Table S1 at http://www.nymc.edu/hotfiles/s3pdebra_bessen.pdf. The aphA3 gene was derived from pDL276 (11); the PCR amplicon included the promoter region of aphA3 but lacked the transcriptional termination loop, in order to minimize a polar effect on transcription of downstream genes. To assemble the linear DNA inactivation cassette, the three amplicons from the first round of PCR were purified, mixed at equimolar ratios, allowed to reanneal at 55°C via their homologous ends, and extended at 68°C in the presence of PCR polymerase mix (TripleMaster; Eppendorf, Westbury, NY) and deoxynucleoside triphosphates. The full-length cassette amplicon was generated via a third round of PCR amplification with primers corresponding to the far ends of the upstream and downstream flanking regions. The composition of the amplified full-length cassette was confirmed by nucleotide sequence determination. The linear DNA was used for electroporation of strain ALAB49 at a concentration of 0.3 μg/μl and settings of 1.75 kV, 400 Ω, and 25 μF in 0.2-cm-electrode-gap cells. Transformants were selected on THY-sheep blood plates containing 500 μg/ml of kanamycin and were evaluated for replacement of the target gene by PCR amplification and nucleotide sequence determination. The ALAB49 ΔspeB mutant was previously described (37).

Mouse model for impetigo.

The hu-skin SCID mouse model for streptococcal impetigo was performed as previously described in extensive detail (33). In brief, human neonatal foreskin was engrafted onto the hind flanks of C.B.-17 scid mice. Healed skin grafts were gently scratched with a scalpel blade and inoculated with 50 μl of bacteria in THY broth. The inoculated bacteria had been freshly grown to mid-logarithmic or stationary phase in THY broth and diluted as appropriate. Actual inoculum doses, expressed as CFU, were ascertained by serial dilutions performed in duplicate and averaged; these values were highly consistent across experiments, except for three data points (plating errors), for which the mean average CFU/ml values from other experiments were used to calculate inoculum dose. Mid-logarithmic phase was defined as the point of half-maximal OD600, whereas stationary-phase cultures were incubated for 24 h. Inoculated skin grafts were occluded with a bandage. At 7 days postinoculation, the human skin grafts were surgically removed from mice and split into two weighed portions. One weighed portion of the graft was evaluated for the number of CFU released following vigorous vortexing, with serial dilutions performed in duplicate; the other portion of the skin was used for histopathology (see below). The number of CFU obtained in a weighed portion of the graft was extrapolated based on the total weight of the graft to determine the total CFU per graft. Spleens were removed and cultured as a measure of systemic infection; in this study, all spleen cultures were negative for bacterial growth.

Histopathology.

Weighed portions of the human skin graft biopsies were formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (33). Sections from each tissue were scored for tissue damage by two investigators in a blinded fashion. Using a severity scale ranging from 0 to 3, grafts were scored for both the extent of inflammation and destruction of the epidermal layer; the two scores were added (for a scale of 0 to 6) and then averaged for the two investigators.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins.

Portions of genes encoding the predicted mature parts of FCT region proteins Cpa, FctA, FctB, and PrtF2, up to but not including the sortase recognition site, were amplified by PCR using strain ALAB49 genomic DNA and cloned into pGEX-3X. Recombinant plasmids were used to transform Escherichia coli, and recombinant polypeptides were expressed as fusions with glutathione S-transferase (GST). Recombinant fusion polypeptides were purified by glutathione-Sepharose affinity chromatography (25). The primers used for PCR amplification are listed in Table S2 at http://www.nymc.edu/hotfiles/s3pdebra_bessen.pdf.

Mutanolysin extraction.

Cell wall extracts of S. pyogenes were prepared using mutanolysin as described previously (28), except that bacteria were grown at 30°C in an attempt to better mimic the optimal conditions established for the T-typing agglutination assay (18). Cells were harvested following growth in THY broth to mid-logarithmic phase (OD600 = 0.350 ± 0.05) or stationary phase (16 h). Extracts from 50 ml of THY broth culture were reduced to a final volume of 400 μl in protoplasting buffer.

Antiserum.

Antiserum specific for the FCT proteins was produced by immunizing rabbits with purified recombinant GST fusion proteins (recombinant Cpa [rCpa], rFctA, and rPrtF2). Rabbits were injected intradermally with 200 μg of recombinant protein in Freund's complete adjuvant, followed by three additional booster doses of 200 μg protein in Freund's incomplete adjuvant every three weeks. T-typing sera (anti-T3, anti-T13, and anti-TB3264) prepared in rabbits and used in immunoblots were purchased from Sevapharma (Prague). Rabbit anti-GST serum was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Immunoblots.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed on gradient gels (4 to 15% acrylamide) under reducing conditions, unless otherwise specified. To account for the increase in bacterial cell mass at stationary phase, the loading volume of the samples obtained from mid-logarithmic phase cultures was increased by 2.5-fold, a value which corresponds to the observed increase in OD600 for the stationary-phase cultures relative to mid-logarithmic-phase cultures. Rabbit sera raised to recombinant GST fusion polypeptides were used at a dilution of 1:2,000. Commercially obtained T-typing sera were used at a dilution of 1:500. Densitometry analysis of immunoreactive material was performed using AlphaEaseFC software (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Lanes were vertically scanned across horizontally defined segments of the immunoblot, and bands were recorded as density peaks. The sum of all peak areas (in pixels) for each lane segment represented the total amount of immunoreactive material.

Cysteine proteinase activity.

Measurement of secreted cysteine proteinase activity in broth culture supernatants was done by an azocasein assay as described previously (37), following bacterial growth in C medium for 20 h at 37°C (13). To ensure that differences in enzymatic activity were not attributable to differences in bacterial cell density, the OD600 of each culture was measured. Activity was calculated based on an A366 value of 0.155 being equivalent to 10 activity units per ml of culture supernatant (37).

HA content.

The hyaluronic acid (HA) content of S. pyogenes, attributed to the polysaccharide capsule, was measured according to previously described methods (38).

Statistical analyses.

GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA) was used to calculate statistical significance using the unpaired t test (two-tailed), the Mann Whitney U test, and the F test for variance for the various data sets of inocula or net changes in graft-recovered CFU among wt ALAB49 and its isogenic mutants. To examine the validity of the t test for these data sets, which require a parametric distribution, the F test was used to compare variances of data for each compared set (i.e., log- versus stationary-phase inoculum for each bacterial construct and wt versus each mutant for both the log- and stationary-phase inocula). For each mutant versus the wt, differences in the inoculum doses were not significant; also, for each mutant, differences in the doses for mid-log- versus stationary-phase inocula were not significant. Only the comparison of wt ALAB49 versus ΔprtF2 mutant stationary-phase inocula yielded an F statistic indicative of significantly different variances; however, the difference between the net change in graft-recovered CFU for wt ALAB49 versus the ΔprtF2 mutant at stationary phase was nonsignificant by both the t test and the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Sample sizes were small for several of the comparisons; however, both the t test and Mann Whitney U-test are conservative and may slightly underestimate the significance of differences between groups having a small sample size.

Nucleotide accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence of the FCT region of wt ALAB49 is assigned GenBank accession number DQ984656.

RESULTS

Nucleotide sequence of the FCT region of an impetigo isolate.

The nucleotide sequence of the FCT region of strain ALAB49 was determined and is depicted in Fig. 1. The FCT region is ∼10.8 kb in length, and eight complete ORFs are evident. Among them are genes encoding a putative signal peptidase (sipA2), a specialized sortase (srtC2), and two regulators of transcription (nra and msmR) having a divergent orientation (1, 29, 32). Four genes encode putative cell wall-anchored surface proteins: cpa, fctA, fctB, and prtF2.

FIG. 1.

FCT region of strain ALAB49. The FCT region of ALAB49 is defined by boundaries of highly conserved ORFs encoding a putative chaperonin at the left flank, which is closest to the origin of replication, and a hypothetical protein at the right flank (5). Four of the FCT region loci encode (putative) cell wall-anchored surface proteins: cpa (encoding collagen-binding protein), fctA (also known as orf100 in M-type 3 strains, orf80 in M-type 5 strains, and eftLSLA in M-type 12 strains), fctB (also known as orf102 in M-type 3 strains, orf82 in M-type 5 strains, and orf2 in M-type 49 strains), and prtF2 (encoding fibronectin-binding protein of the fbaB lineage). The genes nra and msmR encode transcriptional regulators, sipA2 encodes a putative signal peptidase, and srtC2 encodes a sortase.

Cpa, FctA, and PrtF2 are antigenic determinants of T serotype.

Previous studies on several S. pyogenes isolates demonstrate that genes encoding T antigens, which form the basis of the T-serotyping scheme, lie within the FCT region (5, 28). The ALAB49 wt strain was assigned serotype T3/13/B3264 (abbreviated T3/13/B) based on the T agglutination test performed following trypsin treatment of whole bacteria.

The relationship between T-serotype specificity and individual FCT region surface proteins was investigated. Recombinant GST fusion polypeptides corresponding to the predicted, surface-exposed portions of Cpa, FctA, FctB, and PrtF2 were tested by immunoblotting for reactivity with T-type-specific antisera obtained from a commercial source (Fig. 2). Data show that rCpa was strongly bound by each of the anti-T3, anti-T13, and anti-TB3264 sera, whereas rFctA and rPrtF2 were targeted solely by anti-T3 serum. In contrast, rFctB was not specifically recognized by any of the anti-T sera tested (Fig. 2) and yielded background levels equivalent to the GST control antigen (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Immunoreactivity of T-typing sera to FCT region proteins. Immunoblots of recombinant GST-fusion polypeptides (5 μg per lane) were reacted with anti-T3 (α-T3), anti-T13, anti-TB3264, and anti-GST sera. Based on gel migration, the estimated sizes for GST fusion polypeptides rCpa, rFctA, rPrtF2, and rFctB are 76, 57, 121, and 42 kDa, respectively (GST alone is 26 kDa). The gel migration of rPrtF2 (amino acids 38 to 698) is slower than that expected based on the predicted amino acid sequence.

Mutants generated by allelic replacement of each of the three genes encoding anti-T3 serum-reactive proteins of ALAB49 were evaluated for T type by the agglutination assay. Each of the Δcpa, ΔfctA, and ΔprtF2 mutants were T nontypeable. The data support a model in which Cpa, FctA, and PrtF2 comprise an antigenic complex, whereby molecular interactions between Cpa, FctA, and PrtF2 confer resistance to trypsin digestion and/or allow for whole-cell agglutination by T-type-specific antiserum.

Role of T antigens in virulence at the skin.

A humanized mouse model, in which human skin engrafted onto SCID mice is scratched and bacteria are topically applied, was used to study the role of FCT region genes in superficial skin infection by S. pyogenes. Although the hu-skin SCID mouse model does not readily allow for high-throughput analyses, it has important advantages in that it yields high sensitivity (i.e., low inoculum doses lead to infection) and high specificity (i.e., skin strains are more virulent than throat strains) (33, 37, 38). The main outcome measure for “virulence” is the net change (gain or loss) in CFU recovered from the human skin graft relative to the inoculum dose. This measure quantifies a key component of evolutionary success: reproduction of the bacterium at a superficial tissue site. Bacterial growth at the epithelium provides an easy exit for progeny, enabling them to be efficiently transmitted to new hosts in a natural setting. Bacterial growth at the superficial layers of the human skin graft has a highly significant, positive correlation with histopathologic alterations that closely mimic those observed during natural disease (i.e., impetigo) in humans (33, 37, 38), providing further support that this is an ecologically relevant measure for virulence.

The wt strain ALAB49 was highly virulent in the hu-skin SCID mouse model when inoculated following culture to either logarithmic or stationary phase in enriched broth (Fig. 3). The topically delivered inocula that were tested ranged from a high dose of 3 million CFU per skin graft to a dose of as low as ∼300 CFU per graft. All 18 grafts tested displayed a net gain in CFU, indicative of bacterial reproduction at the skin (i.e., virulence). Thus, the hu-skin SCID mouse model displays high sensitivity, where the impetigo-associated ALAB49 wt strain retains its virulence at inoculum doses that probably approach physiological levels in its natural human host.

FIG. 3.

Roles of FCT region genes in virulence at the skin. Bacteria grown to either mid-logarithmic (filled symbols) or stationary (open symbols) phase in broth culture were used to inoculate scratched human skin engrafted on SCID mice. The inoculum dose (log10 CFU) is depicted on the x axis. The net change (increase or decrease) in log10 CFU recovered from a graft at biopsy, relative to the inoculum dose, is shown on the y axis. Each data point represents an inoculated skin graft. Bacterial inocula are indicated for wt ALAB49 and the Δcpa, ΔfctA, and ΔprtF2 mutants. Statistically significant differences (P values for two-tailed unpaired t test) between the net change in graft-recovered CFU for inocula prepared to the logarithmic versus stationary phase of growth are shown. The statistical significances of differences between the net change in graft-recovered CFU for wt ALAB49 versus each of the mutants, for the two inoculum conditions, are reported in the text. All data comparisons that were statistically significant by the unpaired t test were also significant by the Mann-Whitney U test, and vice versa (data not shown). NS, not significant.

The magnitude of the net increase in CFU at 7 days postinoculation tended to be highest for the lower-inoculum doses, exceeding a 10,000-fold increase relative to the lowest dose attempted. Even the highest inoculum doses of wt ALAB49 tested led to consistent recovery of increased numbers of CFU. The data show that there was no statistically significant difference in net bacterial growth at the skin for log- versus stationary-phase inocula. Therefore, wt ALAB49 is highly virulent when applied to scratched human skin following either culture condition.

The roles of Cpa, FctA, and PrtF2 in superficial skin infection were studied by testing single-gene knockout mutants of strain ALAB49 for virulence in the hu-skin SCID mouse model. Attempts to generate an FctB mutant were unsuccessful. Each of the three single-gene mutants corresponding to products of the T-antigen complex were topically applied to scratched skin grafts following culture to either log or stationary phase, and all were tested over a wide range of dose concentrations.

When administered following culture to exponential phase, both the Δcpa and ΔprtF2 mutants displayed a net loss in viability at the skin (Fig. 3). The differences in the net change of graft-recovered CFU following mid-log versus stationary-phase inocula for the Δcpa and ΔprtF2 mutants were highly significant (P = 0.0061 and 0.0013, respectively). Furthermore, both the Δcpa and ΔprtF2 mutants inoculated at log phase showed highly significant decreases in virulence compared to wt ALAB49 inoculated at log phase (P = 0.0006 and 0.0006 for the Δcpa and ΔprtF2 mutants, respectively). All grafts inoculated with wt ALAB49 supported a net gain of bacteria at the skin, whereas all five log-phase inocula with the ΔprtF2 mutant and all five log-phase inocula with the Δcpa mutant resulted in a net loss in CFU.

In contrast to actively growing cultures, both the Δcpa and ΔprtF2 mutants exhibited no loss in virulence when applied to the skin following culture to stationary phase and instead, exhibited a net increase in reproductive growth. The net changes in graft-recovered CFU for wt ALAB49 versus either the Δcpa or ΔprtF2 mutant were comparable, with no statistically significant difference. The findings suggest that the role of Cpa and PrtF2 in virulence at the skin is dependent on the growth phase and/or physiological state of the organism during the transmission process.

The ΔfctA mutant was tested for virulence at the skin following culture in broth to either log or stationary phase (Fig. 3). All eight inoculations with the ΔfctA mutant led to bacterial reproduction at the skin. The data show a lack of a significant difference for the net change in graft-recovered CFU following mid-log versus stationary phase ΔfctA mutant inocula. Furthermore, for inocula from both growth phases, there was no significant difference in virulence between the ΔfctA mutant and wt ALAB49. The data indicate that under the experimental conditions studied, FctA does not play a critical role in superficial infection at the skin. Importantly, the findings on the ΔfctA mutant also suggest that the in vivo alterations observed in the Δcpa mutant are not a consequence of untoward effects on downstream genes.

The hyaluronic acid capsule of S. pyogenes is a virulence factor that can potentially influence the survival of bacteria at the skin (9, 35). In order to rule out a possible role for capsule in the observed losses in virulence in the hu-skin SCID mouse, the HA content was measured for the attenuated mutants of ALAB49. The data indicate that each mutant has a nearly equivalent level of HA compared to that in the parent organism (19.1, 18.3, and 18.8 fg of HA per CFU for the Δcpa mutant, the ΔprtF2 mutant, and wt ALAB49, respectively). Thus, there appears to be a lack of variation in capsule content that would explain the loss of virulence in the Δcpa or ΔprtF2 mutant. In addition, growth curves established by measurements of OD600 in THY broth cultures were identical for wt ALAB49 and all isogenic mutants (data not shown). Thus, the in vivo phenotypes observed for the Δcpa and ΔprtF2 mutants (Fig. 3) appear to be the direct consequence of inactivation of these specific genes.

Expression of FCT region proteins.

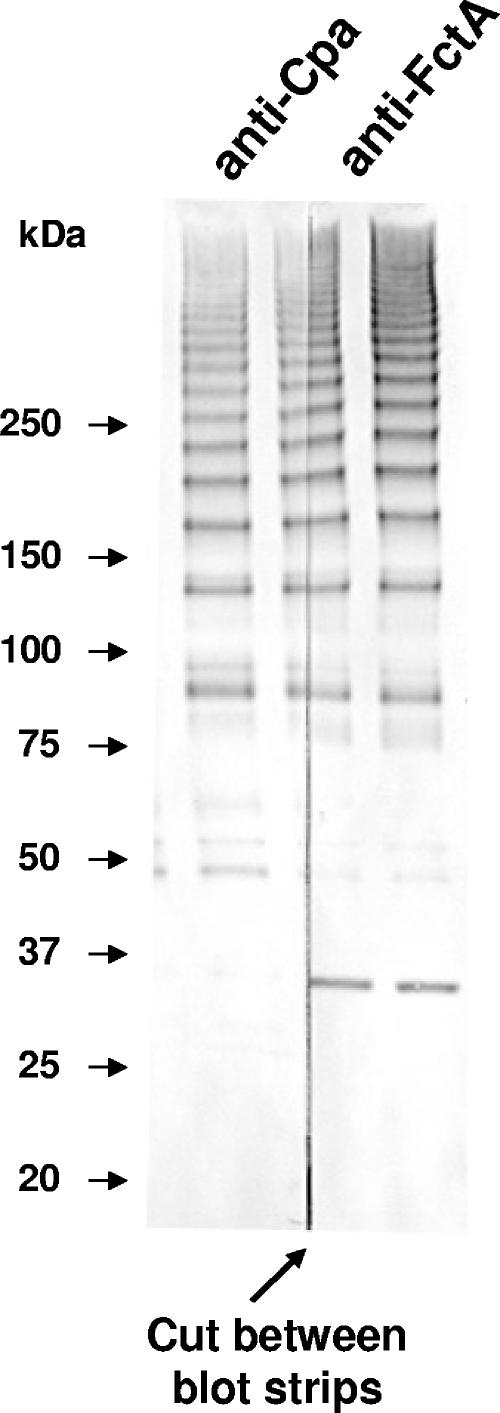

Antibodies raised to recombinant polypeptides of Cpa, FctA, and PrtF2 derived from strain ALAB49 were used to probe bacterial cell extracts by immunoblotting. wt ALAB49 and mutants were grown to either mid-logarithmic or stationary phase, and harvested bacteria were treated with mutanolysin. SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions shows that wt ALAB49 extracts contain a multimeric ladder, with bands migrating from ∼75 kDa to ≫250 kDa that are immunoreactive with both anti-Cpa and anti-FctA sera but not with anti-PrtF2 serum (Fig. 4). Extracts derived from stationary-phase cultures stained more intensely with anti-Cpa and anti-FctA sera than did extracts from logarithmic cultures, perhaps reflecting an accumulation of Cpa and FctA proteins over time. As expected, anti-Cpa and anti-FctA sera exhibited little or no immunoreactivity with extracts derived from the Δcpa and ΔfctA mutants, respectively, indicating that the serum preparations are highly specific for their intended antigenic targets. A characteristic, polymeric ladder on immunoblots targeting FCT region proteins was previously described for S. pyogenes as corresponding to pilus-like appendages in M1, M5, M6, and M12 strains (28); similar ladder-like structures have been attributed to pili in other gram-positive bacteria (3, 10, 23, 26, 41). Thus, the findings for wt strain ALAB49 strongly suggest that both Cpa and FctA are components of pilus-like structures.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblots of mutanolysin extracts from wt ALAB49 and mutants. Mutanolysin extracts of bacteria grown to mid-logarithmic (L) or stationary (S) phase were subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Immunoblots were incubated with rabbit antisera raised to rCpa, rFctA, or rPrtF2. For anti-FctA (α-FctA), one immunoblot was overdeveloped (lower left) in order to illustrate the presence of laddered pilus-like structures in the Δcpa mutant. A second anti-FctA immunoblot (lower right) was underdeveloped, allowing for resolution of the polymeric ladder observed in wt ALAB49 and the ΔprtF2 and ΔspeB mutants. The anti-PrtF2-reactive band migrated slower than for the size predicted for the mature PrtF2 monomeric form (77 kDa), similar to previous observations with cell-extracted and recombinant PrtF2 proteins (30, 44). Densitometry measures for selected lanes are presented in Table 1.

Immunoblots of ALAB49 extracts show that anti-FctA-reactive polymers are evident in the Δcpa mutant; however, they are sharply reduced in quantity and shifted in size relative to the wt (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the Δcpa mutant has an abundance of FctA monomer migrating at the expected size of ∼30 kDa. Quantitative densitometry of stationary-phase extracts indicates that the sum of all anti-FctA-reactive peaks for wt ALAB49 exceeds the sum of all peaks for the Δcpa mutant by only a very slight margin (1.01%) (Table 1). Although densitometry as applied here provides only an estimate, the data indicate that allelic replacement of the upstream cpa gene has no apparent effect on the overall quantity of FctA protein that is produced and extracted via the mutanolysin method.

TABLE 1.

Densitometry scans of immunoreactive cell extracts prepared from ALAB49 at stationary phasea

| Cell extract source | Antiserum | Value (pixels) for sum of peaks (% of total)

|

Approx ratio of polymeric to monomeric form | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lane | Migration of ≥75 kDa | Migration of <75 kDa | |||

| wt | FctAb | 43,453 | 38,261 (88) | 5,192 (12) | 7.4 |

| cpa mutant | FctA | 42,996 | 7,214 (17) | 35,782 (83) | 0.2 |

| wt | Cpa | 29,924 | 28,152 (94) | 1,772 (6) | 15.9 |

| fctA mutant | Cpa | 7,209 | 655 (9) | 6,554 (91) | 0.1 |

Densitometry can be used to estimate the approximate ratio of immunoreactive protein in polymeric versus (mostly) monomeric forms (Table 1). In wt ALAB49, the density of anti-FctA-reactive bands migrating at ≥75 kDa is markedly greater (7.4-fold) than the density of bands migrating at <75 kDa; the latter consist mostly of monomers and perhaps some dimeric forms. In contrast, for the Δcpa mutant, the bulk of the anti-FctA-reactive material has shifted to bands migrating at <75 kDa relative to polymeric forms. Overall, the band density of polymers in the Δcpa mutant is only 19% of that observed in the parental wt strain.

Examination of the ΔfctA mutant reveals that Cpa is present mostly in a monomeric form (∼50 kDa) and that anti-Cpa-reactive polymers are visibly absent (Fig. 4). Densitometry measures of total peaks for stationary-phase extracts immunoreactive with anti-Cpa serum indicate that Cpa is decreased 4.2-fold in the ΔfctA mutant compared to wt ALAB49 (Table 1). In the ΔfctA mutant, the absolute quantity of anti-Cpa-reactive material in polymeric form dropped >40-fold relative to that in wt ALAB49, indicative of a substantial loss in pilus-like structures. Conceivably, the 4.2-fold decrease in total immunoreactive Cpa recovered from the ΔfctA mutant may be a consequence of altered cell surface processing of Cpa, less efficient extraction of Cpa monomers via mutanolysin, or differences in the antigenic structure of the monomeric form. Another plausible explanation is that cell wall anchoring of Cpa is diminished in the absence of FctA, resulting in increased secretion of Cpa into the culture supernatant; however, this possibility was ruled out by via immunoblot analysis of culture supernatants (data not shown). It is important to note that the decrease in immunoreactive Cpa observed for the ΔfctA mutant has no apparent effect on virulence in vivo (Fig. 3).

That the ladder-like structure observed for wt ALAB49 corresponds to a heteropolymer comprised of both FctA and Cpa is further evidenced by the precise juxtaposition of bands on immunoblots containing wt ALAB49 cell extracts treated with antiserum specific for either Cpa or FctA (Fig. 5). Taken together with the findings on the Δcpa and ΔfctA mutants (Fig. 4) (Table 1), the data suggest that both FctA and Cpa are main structural components of pilus-like appendages. Polymer formation appears to be highly dependent on FctA but may also occur at a low residual level in the absence of Cpa.

FIG. 5.

Cpa and FctA form a heteropolymer. Mutanolysin extracts from wt ALAB49 grown 16 h at 30°C were loaded onto three lanes and subjected to SDS-PAGE and electrotransfer; the blot was split down the middle of the center lane and the two halves incubated with antiserum raised to rCpa or rFctA polypeptide.

The immunoreactive bands observed with anti-Cpa and anti-FctA sera were unaltered in the ΔprtF2 mutant relative to the parental strain, suggesting that PrtF2 is not a component of the pilus-like polymer (Fig. 4). Mutanolysin extracts from the ALAB49 wt strain show that the anti-PrtF2 serum does not react with the polymeric ladders, but rather, it recognizes a major band migrating at ∼100 kDa which is present in extracts from cells cultured to mid-log phase but is absent from stationary-phase cells. Nonreducing conditions yielded a similar staining pattern (data not shown), indicating that PrtF2 is not covalently linked to Cpa or FctA. Furthermore, the pattern of anti-PrtF2 immunoreactivity was unaltered in the Δcpa and ΔfctA mutants (Fig. 4). Thus, despite its necessity in formation of the T3/13/B antigenic complex, PrtF2 is not associated with the pilus-like structure under these denaturing conditions.

Influence of SpeB on PrtF2.

Previous studies showing that secreted cysteine protease activity due to SpeB reaches its peak during stationary phase (37) and that SpeB degrades PrtF2 (44) prompted further evaluation of PrtF2 in the ΔspeB mutant. The data indicate that inactivation of speB leads to the accumulation of PrtF2 in stationary-phase extracts (Fig. 4). The immunoreactive bands observed with anti-Cpa and anti-FctA sera were unaltered in the ΔspeB mutant compared to wt ALAB49, suggesting that neither Cpa or FctA is a target of SpeB degradation when present in its native form. Thus, SpeB appears to enzymatically degrade PrtF2 during the stationary phase of growth but has no effect on the FctA- and Cpa-containing heteropolymer. Like the parental strain, the ΔspeB mutant is T3/13/B by the T agglutination test.

SpeB is essential for virulence in the hu-skin SCID mouse when grafts are topically inoculated with ΔspeB mutants cultured to stationary phase (37). The speB locus lies outside the FCT region, positioned ∼300 kb distant in S. pyogenes strains whose complete genome sequences have been determined (data not shown). In the present study, the ALAB49 ΔspeB mutant was grown to exponential phase and tested for virulence (Fig. 6). Unlike the Δcpa and ΔprtF2 mutants, the ΔspeB mutant showed no net change in graft-recovered CFU following mid-log- versus stationary-phase inocula (P = not significant; unpaired t test, two tailed). Also, experimental findings demonstrate a statistically significant loss in virulence when the ΔspeB mutant grown to log phase is compared to wt ALAB49 (P = 0.0001). Thus, SpeB appears to be critical for virulence at the skin regardless of the growth state of the infecting organism.

FIG. 6.

Lack of effect of growth phase on virulence of the ΔspeB mutant. Bacteria grown to either mid-logarithmic (filled symbols) or stationary (open symbols) phase in broth culture were used to inoculate scratched human skin engrafted on SCID mice. Bacterial inocula consist of wt ALAB49 (circles) or the ΔspeB mutant (squares). The inoculum dose (log10 CFU) is depicted on the x axis. The net change (increase or decrease) in log10 CFU recovered from a graft at biopsy, relative to the inoculum dose, is shown on the y axis. Each data point represents an inoculated skin graft. Statistical analysis is described in the Fig. 3 legend and reported in the text. Data on the ΔspeB mutant inoculated at stationary phase were previously reported (37).

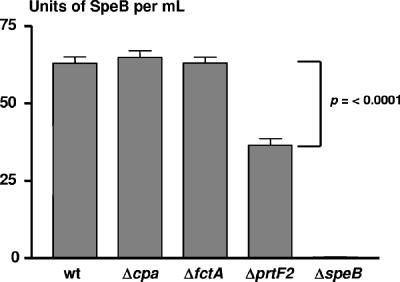

Since SpeB is a key factor for virulence at the skin (37), the FCT region gene mutants were examined for SpeB expression. The ΔprtF2 mutant displayed ∼57% (36.5 U/ml) of the level of secreted cysteine protease activity which was observed in wt ALAB49, the Δcpa mutant, and the ΔfctA mutant (63, 65, and 63 U/ml, respectively) (Fig. 7). The 1.7-fold reduction in SpeB activity of the ΔprtF2 mutant, relative to the parent strain, is statistically significant. The possibility exists that attenuation of the ΔprtF2 mutant is ultimately due to a defect in the formation of enzymatically active SpeB (7, 46). Yet, the ALAB49 ΔprtF2 mutant expresses levels of cysteine protease activity comparable to those of its close genetic relative, the wt 29487 strain (33.9 U/ml), which, like wt ALAB49, is highly virulent in the hu-skin SCID mouse via a SpeB-dependent mechanism (27, 37). Therefore, even though cysteine activity is slightly depressed in the ALAB49 ΔprtF2 mutant, it appears to be present in sufficient quantities.

FIG. 7.

Secreted cysteine proteinase activity of mutants. Secreted cysteine proteinase activity due to SpeB, present in culture broth supernatants, was measured for wt ALAB49 and mutants by using the azocasein substrate assay. The mean average OD600 for all cultures was 0.646 ± 0.007, indicating that bacterial cell density was highly even across all samples. Data shown are compiled from two separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. The P value was calculated using the unpaired t test (two tailed).

Histopathology of human skin grafts.

Previous histopathologic analyses of skin graft biopsies demonstrated a strong correlation between tissue damage and bacterial growth at the skin (33, 38). Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained tissue sections of the skin graft biopsies of this report were scored for the extent of inflammation and epidermal destruction, using a scale ranging from 0 (unaltered tissue) to 6 (extensive alterations). The 35 grafts displaying a net increase in CFU had an average mean histological score of 3.60 ± 0.44 (data not shown). In contrast, for 18 of the 19 grafts showing a net decrease in CFU, the average mean histological score was 0.54 ± 0.33 (one graft was not scored). The difference in histological scores of tissue alteration and damage for grafts with a net increase versus a decrease in CFU was highly significant (P < 0.0001, by both the unpaired t test and Mann Whitney U test). These data confirm previous findings showing that bacterial growth at the skin is strongly linked to pathological processes.

DISCUSSION

Pili often act to enhance the adherence of bacteria to the host epithelium. The hu-skin SCID mouse model is optimized to measure key features of superficial infection, via topical application of bacteria onto small breaks in the keratinized layer. A surprising finding of this study is that the loss of the pilus-like polymer, as observed for the ΔfctA mutant, has no measurable effect on streptococcal virulence at the skin when studied in the humanized mouse.

Unlike the ΔfctA mutant, the Δcpa mutant displays attenuated virulence at the skin. The Cpa protein of ALAB49 is a putative MSCRAMM having collagen-binding activity, and its predicted sequence has a partial match with the consensus sequence for the collagen-binding site of an M49 strain (21). The well-characterized Cpa protein of the M49 strain binds human collagen type I, a form that is present in abundance within the dermal layer of human skin. Whether or not Cpa of ALAB49 binds to collagen type I with equally high affinity remains to be established. Immunogold electron microscopy directed to Cpa of an M1 strain shows abundant cell surface staining, with relatively less staining at distal sites as is typical for extended pili (28). The findings presented in this report for the ALAB49 impetigo isolate indicate that the contribution of Cpa to superficial skin infection does not require FctA or an intact pilus.

Like Cpa, PrtF2 is essential for superficial skin infection when the bacterium is transmitted in an exponential growth state. The PrtF2 protein of ALAB49 shares extensive sequence identity with the FbaB-like form of PrtF2 (data not shown), whose direct role in binding to fibronectin has been established (39). Thus, based on structural homology, it seems likely that the PrtF2 protein of ALAB49 binds to fibronectin. Since the ΔprtF2 and Δcpa mutants are both attenuated for virulence under similar conditions, neither PrtF2 nor Cpa can fully compensate for the loss of the other. Thus, adherence of streptococci to the epidermis may require engagement of multiple targets within the host extracellular matrix. The data presented here are suggestive of a synergistic interaction between Cpa and PrtF2. However, since stationary-phase bacteria require neither of these two MSCRAMMs, there must also exist an independent mechanism for mediating attachment to the epithelium.

The effects of bacterial growth phase on the in vitro and in vivo properties of several S. pyogenes virulence factors are summarized in Table 2. The physiological state of streptococci that are successfully transmitted to new hosts under natural conditions is not known, but the ALAB49 wt strain seems to have the capacity to infect the skin in either growth state. The secreted cysteine proteinase SpeB degrades surface-bound PrtF2 during stationary phase, whereas during log phase, SpeB activity is repressed (37) and PrtF2 structure is preserved. Inactivation of prtF2 has no negative effect on virulence following inoculation at stationary phase, when SpeB activity is maximal. It makes sense that the influence of PrtF2 on virulence is most profound when bacteria are transmitted in a logarithmic state. Yet, the ΔspeB mutant is severely attenuated in the humanized mouse regardless of its input growth state. These data suggest that PrtF2 acts early during the course of infection that is initiated by organisms which are transmitted to the host during active growth. In contrast, it seems that SpeB is unnecessary, or even contraindicated, for the early stages of infection following transmission of actively growing bacteria. Although it is unclear whether SpeB is required for nongrowing organisms during transmission and/or early steps of infection, it appears that at least a critical part of every skin infectious process requires streptococci to pass through steady-state growth or a metabolic equivalent, in which SpeB activity is turned on.

TABLE 2.

Growth phase dependence for roles of virulence factors in superficial skin infection

| Virulence factor | Bacterial cell localization | Log phase

|

Stationary phase

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype expression | Necessary for skin infection | Phenotype expression | Necessary for skin infection | ||

| Cpa | Surface | On | Yes | On | No |

| FctA | Surface | On | No | On | No |

| PrtF2 | Surface | On | Yes | Off | No |

| SpeB | Secreted | Off | Yes | On | Yes |

The predicted cpa and prtF2 products of strain ALAB49 each have an E-box motif positioned on the NH2-terminal side of the consensus collagen- and fibronectin-binding sites, respectively (data not shown). The significance of the E box lies in its presence within pilus-associated proteins of many other gram-positive bacterial species; the conserved glutamic acid within the E box of SpaA of Corynebacterium diphtheriae is essential for the incorporation of some proteins into pilus structures (26, 41). Data in this report provide strong evidence that Cpa is covalently linked to FctA, giving rise to a heteropolymer. Despite the presence of an E-box motif within PrtF2, covalent linkage between PrtF2 and either Cpa or FctA was not detected in mutanolysin-derived cell extracts. Conceivably, the detergent treatment used in SDS-PAGE disrupts a PrtF2-pilus interaction, but it would most likely be noncovalent in nature. PrtF2 constitutes a critical part of the T3/13/B antigenic complex, but it is not yet clear whether PrtF2 serves as a well-placed target for antibody-mediated bacterial cell agglutination and/or may be an intrinsic part of the pilus-like appendage.

Surprisingly, the FctA protein is expendable in the hu-skin SCID mouse. If FctA is indeed critical for natural infection at the skin in a human host population, then it stands to reason that the topical mode of bacterial delivery in the humanized mouse preempts the FctA-dependent step. This would place the FctA-mediated event at a very early stage of the infectious process. If the function of the Cpa-FctA polymer is to make initial contact with the host epithelium, topical application of the bacterium may circumvent this need by allowing other bacterial adhesins, such as surface envelope-bound Cpa and PrtF2, to engage their host receptors in an efficient manner.

An alternative possibility is that pilus-like appendages are not at all essential for skin infection but rather play a key role at the throat. Unlike at the skin surface, streptococci in the upper respiratory tract must overcome the flow of overlying fluid in order to attach to mucosal epithelial surfaces, and perhaps extended pili provide the anchor. If this is true for S. pyogenes, then it stands to reason that the so-called skin strains, such as ALAB49, produce pili because the throat serves as a critical reservoir. Asymptomatic throat colonization following impetigo is well-documented (6), but the extent to which throat colonization by skin strains leads to new transmission events resulting in fresh impetigo lesions is much less clear. In one population-based study of a tropical community with endemic levels of impetigo, asymptomatic throat colonization occurred at a very low level (4). Thus, in this situation, throat-directed pili present on skin strains would seem to serve no purpose. However, perhaps there are other host populations and environmental conditions in which the so-called skin strains more heavily rely on colonization at the throat for their long-term survival. Another plausible explanation for the nonrequirement of FctA in the humanized mouse is that, in the natural world, streptococci achieve a physiological state that was not captured in this study but for in which FctA is essential.

The hu-skin SCID mouse model for streptococcal impetigo, employing topical application of bacteria onto slightly broken skin, is well-suited for study of the highly prevalent, superficial infections caused by this global pathogen. The high sensitivity of the humanized mouse is underscored by the low infective dose achieved with the ALAB49 strain (<500 CFU). Indeed, the effects of Cpa and PrtF2 on streptococcal virulence are subtle and are detected only under limited growth conditions. Many bacterial pathogens have multiple virulence factors with seemingly redundant functions, and the fibronectin-binding proteins of S. pyogenes provide a case in point, where at least six loci (fbp54, fbaA, prtF1/sfbI, prtF2/pfbpI/fbaB, sof/sfbII, and sfbX) loci give rise to this functional class of protein (8, 15, 17, 20, 22, 39). The pathogen-host interaction is complex, and with an ever-changing microenvironment, the successful pathogen may require multiple molecular strategies to achieve the same outcome.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Jing Sun, Alicia Bennett, and Zerina Kratovac for technical assistance; to Dee Jackson and Bernie Beall (CDC) for T-serotype determination; and June Scott for helpful insights.

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant AI-053826) and the American Heart Association (to D.E.B.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett, T. C., A. R. Patel, and J. R. Scott. 2004. A novel sortase, SrtC2, from Streptococcus pyogenes anchors a surface protein containing a QVPTGV motif to the cell wall. J. Bacteriol. 186:5865-5875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett, T. C., and J. R. Scott. 2002. Differential recognition of surface proteins in Streptococcus pyogenes by two sortase gene homologs. J. Bacteriol. 184:2181-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barocchi, M. A., J. Ries, X. Zogaj, C. Hemsley, B. Albiger, A. Kanth, S. Dahlberg, J. Fernebro, M. Moschioni, V. Masignani, K. Hultenby, A. R. Taddei, K. Beiter, F. Wartha, A. von Euler, A. Covacci, D. W. Holden, S. Normark, R. Rappuoli, and B. Henriques-Normark. 2006. A pneumococcal pilus influences virulence and host inflammatory responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2857-2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bessen, D. E., J. R. Carapetis, B. Beall, R. Katz, M. Hibble, B. J. Currie, T. Collingridge, M. W. Izzo, D. A. Scaramuzzino, and K. S. Sriprakash. 2000. Contrasting molecular epidemiology of group A streptococci causing tropical and non-tropical infections of the skin and throat. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1109-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bessen, D. E., and A. Kalia. 2002. Genomic localization of a T serotype locus to a recombinatorial zone encoding extracellular matrix-binding proteins in Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 70:1159-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bisno, A. L., and D. Stevens. 2000. Streptococcus pyogenes (including streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis), p. 2101-2117. In G. L. Mandell, R. G. Douglas, and R. Dolin (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 5th ed., vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collin, M., and A. Olsen. 2000. Generation of a mature streptococcal cysteine proteinase is dependent on cell wall-anchored M1 protein. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1306-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Courtney, H. S., J. B. Dale, and D. I. Hasty. 1996. Differential effects of the streptococcal fibronectin-binding protein, FBP54, on adhesion of group A streptococci to human buccal cells and HEp-2 tissue culture cells. Infect. Immun. 64:2415-2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darmstadt, G., L. Mentele, A. Podbielski, and C. Rubens. 2000. Role of group A streptococal virulence factors in adherence to keratinocytes. Infect. Immun. 68:1215-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dramsi, S., E. Caliot, I. Bonne, S. Guadagnini, M. C. Prevost, M. Kojadinovic, L. Lalioui, C. Poyart, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2006. Assembly and role of pili in group B streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1401-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunny, G. M., L. N. Lee, and D. J. LeBlanc. 1991. Improved electroporation and cloning vector system for gram-positive bacteria Appl. Environ Microbiol. 57:1194-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fogg, G. C., C. M. Gibson, and M. G. Caparon. 1994. The identification of Rofa, a positive-acting regulatory component of Prtf expression: use of an M-gamma-delta-based shuttle mutagenesis strategy in Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 11:671-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerlach, D., W. Knoll, W. Kohler, J. H. Ozegowski, and V. Hribalova. 1983. Isolation and characterization of erythrogenic toxins. V. Identity of erythrogenic toxin type B and streptococcal proteinase precursor. Zbl. Bakt. Hyg. I Abt. Orig. 255:221-233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton, H. L., and J. P. Dillard. 2006. Natural transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: from DNA donation to homologous recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 59:376-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanski, E., and M. Caparon. 1992. Protein F, a fibronectin-binding protein, is an adhesin of the group A streptococcus Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6172-6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hava, D., and A. Camilli. 2002. Large-scale identificationof serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1389-1405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeng, A., V. Sakota, Z. Y. Li, V. Datta, B. Beall, and V. Nizet. 2003. Molecular genetic analysis of a group A Streptococcus operon encoding serum opacity factor and a novel fibronectin-binding protein, SfbX. J. Bacteriol. 185:1208-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, D. R., E. L. Kaplan, J. Sramek, R. Bicova, J. Havlicek, H. Havlickova, J. Motlova, and P. Kriz. 1996. Laboratory diagnosis of group A streptococcal infections. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 19.Johnson, D. R., E. L. Kaplan, A. VanGheem, R. R. Facklam, and B. Beall. 2006. Characterization of group A streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes): correlation of M-protein and emm-gene type with T-protein agglutination pattern and serum opacity factor. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:157-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreikemeyer, B., D. R. Martin, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1999. SfbII protein, a fibronectin binding surface protein of group A streptococci, is a serum opacity factor with high serotype-specific apolipoproteinase activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 178:305-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreikemeyer, B., M. Nakata, S. Oehmcke, C. Gschwendtner, J. Normann, and A. Podbielski. 2005. Streptococcus pyogenes collagen type I-binding Cpa surface protein: expression profile, binding characteristics, biological functions, and potential clinical impact. J. Biol. Chem. 280:33228-33239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreikemeyer, B., S. Talay, and G. Chhatwal. 1995. Characterization of a novel fibronectin-binding surface protein in group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 17:137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauer, P., C. D. Rinaudo, M. Soriani, I. Margarit, D. Maione, R. Rosini, A. R. Taddei, M. Mora, R. Rappuoli, G. Grandi, and J. L. Telford. 2005. Genome analysis reveals pili in group B streptococcus. Science 309:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeMieux, J., D. L. Hava, A. Basset, and A. Camilli. 2006. RrgA and RrgB are components of a multisubunit pilus encoded by the Streptococcus pneumoniae rlrA pathogenicity islet. Infect. Immun. 74:2453-2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lizano, S., and K. H. Johnston. 2005. Structural diversity of streptokinase and activation of human plasminogen. Infect. Immun. 73:4451-4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marraffini, L. A., A. C. DeDent, and O. Schneewind. 2006. Sortases and the art of anchoring proteins to the envelopes of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:192-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGregor, K. F., B. G. Spratt, A. Kalia, A. Bennett, N. Bilek, B. Beall, and D. E. Bessen. 2004. Multilocus sequence typing of Streptococcus pyogenes representing most known emm types and distinctions among subpopulation genetic structures. J. Bacteriol. 186:4285-4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mora, M., G. Bensi, S. Capo, F. Falugi, C. Zingaretti, M. A. G. O., T. Maggi, A. R. Taddei, G. Grandi, and J. L. Telford. 2005. Group A streptococcus produce pilus-like structures containing protective antigens and Lancefield T antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:15641-15646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakata, M., A. Podbielski, and B. Kreikemeyer. 2005. MsmR, a specific positive regulator of the Streptococcus pyogenes FCT pathogenicity region and cytolysin-mediated translocation system genes. Mol. Microbiol. 57:786-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandiripally, V., L. Wei, C. Skerka, P. F. Zipfel, and D. Cue. 2003. Recruitment of complement factor H-like protein 1 promotes intracellular invasion by group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 71:7119-7128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pizarro-Cerda, J., and P. Cossart. 2006. Bacterial adhesion and entry into host cells. Cell 124:715-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podbielski, A., M. Woischnik, B. A. B. Leonard, and K. H. Schmidt. 1999. Characterization of nra, a global negative regulator gene in group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1051-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scaramuzzino, D. A., J. M. McNiff, and D. E. Bessen. 2000. Humanized in vivo model for streptococcal impetigo. Infect. Immun. 68:2880-2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneewind, O., K. F. Jones, and V. A. Fischetti. 1990. Sequence and structural characterization of the trypsin-resistant T6 surface protein of group A streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 172:3310-3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrager, H., S. Alberti, C. Cywes, G. Dougherty, and M. Wessels. 1998. Hyaluronic acid capsule modulates M protein-mediated adherence and acts as a ligand for attachment of group A streptococcus to CD44 on human keratinocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 101:1708-1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shevchuk, N. A., A. V. Bryksin, Y. A. Nusinovich, F. C. Cabello, M. Sutherland, and S. Ladisch. 2004. Construction of long DNA molecules using long PCR-based fusion of several fragments simultaneously. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svensson, M. D., D. A. Scaramuzzino, U. Sjobring, A. Olsen, C. Frank, and D. E. Bessen. 2000. Role for a secreted cysteine proteinase in the establishment of host tissue tropism by group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 38:242-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svensson, M. D., U. Sjobring, F. Luo, and D. E. Bessen. 2002. Roles of the plasminogen activator streptokinase and plasminogen-associated M protein in an experimental model for streptococcal impetigo. Microbiology 148:3933-3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terao, Y., S. Kawabata, M. Nakata, I. Nakagawa, and S. Hamada. 2002. Molecular characterization of a novel fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes strains isolated from toxic shock-like syndrome patients. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47428-47435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, C. M. Fraser, et al. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ton-That, H., L. A. Maraffini, and O. Schneewind. 2004. Sortases and pilin elements involved in pilus assembly of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Mol. Microbiol. 53:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ton-That, H., and O. Schneewind. 2004. Assembly of pili in Gram-positive bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 12:228-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waldor, M., and J. Mekalanos. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei, L., V. Pandiripally, E. Gregory, M. Clymer, and D. Cue. 2005. Impact of the SpeB protease on binding of the complement regulatory proteins factor H and factor H-like protein 1 by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 73:2040-2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, H., and P. M. Fives-Taylor. 1999. Identification of dipeptide repeats and a cell wall sorting signal in the fimbriae-associated adhesin, Fap1, of Streptococcus parasanguis. Mol. Microbiol. 34:1070-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmerlein, B., H. S. Park, S. Y. Li, A. Podbielski, and P. P. Cleary. 2005. The M protein is dispensable for maturation of streptococcal cysteine protease SpeB. Infect. Immun. 73:859-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]